THE TUSCAN GALLERIES.

Now, go along the Michael Angelo corridor as far as the Long Gallery, and pass into the Sala Prima Toscana.

This contains works of the earlier mediæval type, the culminating point of Giottesque painting.

In front of you as you enter, on easels in the middle, are two of the noblest and most beautiful pictures of the early fifteenth century. That to the left is * *Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi, the most gorgeous altar-piece of the Early Umbrian School, still enclosed in its original setting of three arches. This great work, which comes from the Sacristy of Santa Trinità in Florence, should be closely studied in all its details. Contrary to custom, the Madonna occupies the left field. The ruined temple and shed to the left, the attendants examining the Elder King’s gift, the group of the Madonna and Child, with Joseph in his conventional yellow robe, and the Star which stands “over the place where the young Child was,” should all be observed and compared with other pictures. (I may mention parenthetically that the Star of Bethlehem in Adorations is in itself worth study, being sometimes inscribed with the human face, and sometimes developed in curious fashions.) Examine also the group of the Three Kings, the eldest of whom, as usual, is kneeling, having presented his gift and removed his crown; while the second is in the act of offering, and the third and youngest, just dismounted from his horse, is having his spurs removed by an obsequious attendant. The exquisite decorative work of their robes, the finest product of the Early Umbrian School, deserves close attention. Note, next, the cavern of the Apocryphal Gospels in the background, with the inevitable ox and ass of the Nativity. The two or three servants who formed the sole train of the Magi in earlier works have here developed into a great company of attendants, mounted on horses and camels, to mark their Oriental origin, and dressed in what Gentile took to be the correct costumes of Asia and Africa. Note the excellent drawing (for that date) of some of the horses, and the tolerably successful attempts at foreshortening. Observe likewise the monkeys, the hunting leopard, the falcons, and the other strange animals in the train of the Kings, to suggest Orientalism. All this part of the picture should be closely compared with the inexpressibly lovely Benozzo Gozzoli of the Procession of the Kings in the Riccardi Palace. The face of the Young King is repeated in one of the suite to the extreme right. Examine all these faces separately, and observe their characterisation. Do not overlook the fact that the principal ornaments in this splendid picture are raised in plaster or gesso-work, and then gilt and painted.

GENTILE DA FABRIANO. — ADORATION OF THE MAGI.

The background of the main picture also contains three separate scenes of the same history. In the left arch, the Three Kings, in their own country, behold the Star from the summit of a mountain. In the centre arch, they ride in procession to enter Jerusalem and inquire the way of Herod. In the right arch, they are seen returning to their own country. Do not be satisfied, however, with merely identifying these points to which I call attention; if you look for yourself, you will find others in abundance well worth your notice. This is a picture before which you should sit for long periods together.

Two subjects remain in the predella, the third is missing here (now in the Louvre, Presentation in the Temple). To the left is the Nativity, with the angels appearing to the shepherds. In the centre is the Flight into Egypt.

The gable-ends or cuspidi also contain figures, which do not seem to me by the same hand. On the right and left is the Annunciation, in two separate lozenges; in the centre, the Eternal Father, blessing. The scrolls with names will enable you to identify the recumbent kings and prophets.

This picture, dated 1423, strikes the key-note for early Umbrian art. Observe how its Madonna leads gradually up to Perugino and Raphael. Softness, ecstatic piety, and elaborate decoration are Umbrian notes. You cannot study this work too long or too carefully.

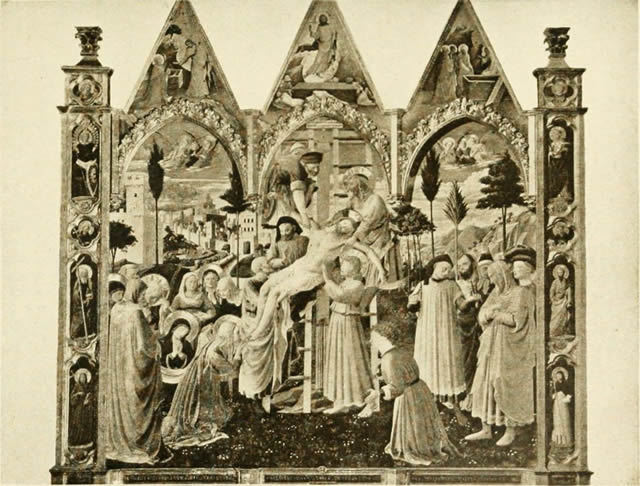

FRA ANGELICO. — DESCENT FROM THE CROSS.

The second of these great pictures is Fra Angelico’s Descent from the Cross, — his finest work outside the realm of fresco. This also deserves the closest study. Observe that, in spite of its large size, it is essentially miniature. To the left is the group of the Mater Dolorosa and the mourning Maries. Hard by, the Magdalen, recognisable (as always) by her long golden hair, is passionately kissing the feet of the dead Saviour. St. Nicodemus and St. Joseph of Arimathea, — the latter a lovely face, — distinguished by their haloes, are letting down the sacred body from the Cross, which St. John and another believer receive below. To the extreme right is a group of minor disciples, one of whom (distinguished by rays, but I cannot identify him) exhibits the Crown of Thorns and the three nails to the others. The figure in red in the foreground is possibly intended for St. Longinus. Above, in the arches, are sympathising angels. This is a glorious work, full of profound feeling. The towers and wall of the city, recalling those of Florence, should also be noticed. The trees and landscape are still purely conventional.

On the frame are figures of saints: to the left St. Michael the Archangel, a glorious realisation; St. Francis with the Stigmata; St. Andrew; and St. Bernardino of Siena; to the right St. Peter with the keys; St. Peter Martyr with his wounded head; St. Paul with the sword (observe the type); and a bearded St. Dominic, with his red star and lily. In the gable ends or cuspidi are three saints by Don Lorenzo Monaco, who can usually be recognised by the extreme length and curious bend of his figures. (See him better at the Uffizi.) On the left are Christ and the Magdalen in the garden; in the centre, the Resurrection; on the right, the three Maries at the tomb. Compare with the Annunciation just to the right on the wall, by the same painter.

Now begin at the left wall by the door. These pictures represent the earliest art of Tuscany, and are mostly altar-pieces.

High up is a curious “Byzantine” (say rather, barbaric) figure of St. Mary Magdalen, as the Penitent in Provence (see Mrs. Jameson). As always in this subject, she is clad entirely in her own hair, which the modesty of the early Christian artist has represented as covering her from head to foot like a robe. It is here rather red than golden. She holds a scroll with the rhyming Latin inscription, —

|

Ne desperetis, vos qui peccare soletis, Exemploque meo vos reparate Deo: |

that is to say: “Despair not ye who are wont to sin, and by my example make your peace with God.” At its sides are eight small stories from the life of the saint, biblical and legendary. Beginning at the top, on the left is the Magdalen washing the feet of Christ; the canopy represents a house; the tower shows that it takes place in a city; on the right, the Resurrection of Lazarus, represented (as in all early pictures) as a mummy; note the tower, and the bystanders holding their noses. In the second tier: on the left are Christ and the Magdalen in the garden; on the right, she goes to Marseilles, with Martha and St. Maximin, and converts the people of that city, which observe in the background. In the third tier: on the left, she takes refuge as a penitent, now clad only in her luxuriant hair, in the Sainte Baume (a holy cave in Provence), where she is daily raised to see the Beatific Vision by four angels. (Look out for later representations of this subject, often improperly described as the Assumption of the Magdalen.) On the right, the Magdalen, at the mouth of the cave, has the holy wafer brought her by an angel. In the fourth tier: on the left, St. Maximin, warned by an angel that the Magdalen is dying, brings her the Holy Sacrament to her cave; on the right, he buries the Magdalen at Marseilles; canopy and tower again representing church and city.

Beneath this, 100, is a similar early figure of St. John in the desert, with his own head in a charger before him: ill described as Byzantine.

Number 101 is a curious barbaric picture of Madonna and saints, with scenes from the life of Christ: brought from the Franciscan convent of Santa Chiara at Lucca. The saints can be sufficiently identified by their inscriptions. Compare the quaint St. Michael with Fra Angelico’s, and the St. Anthony and St. Francis with those later types with which we are already familiar. Never forgot that these rude early works form the basis of all later representations. Notice Santa Chiara, to whom the work is dedicated (see Baedeker, Assisi).

Number 102, a Cimabue, Madonna and angels, resembles the picture in Santa Maria Novella, but with a considerable variation in the angelic figures, here rather less successful. It is, I think, an earlier picture. Beneath it are four prophets in an arcade, holding scrolls with inscriptions from their own writings, interpreted by mediæval theologians as prophecies of the Holy Virgin.

Next it, 103, is a similar altar-piece by Giotto, with same central subject, where the difference of treatment and the advance in art made by the great painter are tolerably conspicuous. At the same time, Giotto is never by any means so interesting or free in altar-pieces as in fresco. The best figures here are the angels in the foreground. The details of both these pictures deserve attentive study and comparison.

Then, 116, Taddeo Gaddi, the Entombment, with the risen Christ in a mandorla above, and angels exhibiting the instruments of the Passion. The attendant St. John and other figures in this fine work should be compared with the corresponding personages in Fra Angelico’s Descent from the Cross. They serve to show how much the Friar of San Marco borrowed from his predecessors, and how far he transformed the conceptions he took from them. This is one of the best altar-pieces of the school of Giotto. Do not hurry away from it. The OSM stands for Or San Michele, from which church the picture comes.

Number 127 is an Agnolo Gaddi, Madonna and Child, with six Florentine saints. Note the dates and succession in time of all these painters. Compare the central panel with the Giotto close by to show its ancestry. The other saints are St. Pancratius (from whose church and high altar it comes); St. Nerius; St. John the Evangelist; St. John the Baptist; St. Achileus; and Santa Reparata of Florence. For these very old Roman saints, little known in Florence save at this ancient church, consult Mrs. Jameson. Omit the predella for the moment.

GIOTTO. — ADORATION OF THE MAGI.

Beneath these pictures is a set of panels, attributed to Giotto, and representing scenes in the life of Christ. They originally formed part of a chest or cupboard in the sacristy of the church of Santa Croce in Florence, as the very similar series by Duccio still do at Siena; (if you go to Siena, you should compare the two). Though not important works, they deserve study from the point of view of development. Note, for example, in the first of the series, the Visitation, the relative positions of the Madonna and St. Elizabeth, and the arch in the background — an accessory which afterward becomes of such importance in the Pacchiarotto in an adjacent room, and in the Mariotto Albertinelli in the Uffizi. Observe, similarly, the quaint Giottesque shepherds in the second of the series: their head-dress is characteristic; you will meet it in many Giottos. The Magi, with their one horse each, may be well compared with the accession of wealth in Gentile da Fabriano; while the position of the elder king and the crown of the second are worth notice for comparison. Observe how almost invariably the eldest king has removed his crown and presented his gift at the moment of the action. Earlier works are always simpler in their motives: never forget this principle. Not less characteristic is the Presentation in the Temple, with fire in the altar, where the figures of St. Joseph, on the right, and St. Simeon, on the left, are extremely typical. The Baptism has the unusual feature of the Baptist and the angels on the same bank, while a second figure waits beyond with the towel. The Transfiguration prepares you for Fra Angelico’s in St. Marco. The Last Supper, with Judas leaving the table, is an interesting variant. The Resurrection shows most of the conventional features. The Doubting Thomas also sheds light on subsequent treatments.

Compare these works with those in the predella of the Agnolo Gaddi, where the story of Joachim and Anna, with which you are now, I hope, familiar, is similarly related. Joachim expelled from the Temple, with the angel announcing to him the future birth of the Virgin, ought by this time to be a transparent scene. In the Meeting at the Golden Gate you will recognise the angel who brings together the heads of wife and husband, as in the lunette at Santa Maria Novella. The Birth of the Virgin has, in a very simple form, all the characteristic elements of this picture. So has the Presentation in the Temple, with its flight of steps and its symbolical building. Most interesting of all is the Annunciation, which should be closely compared with similar representations.

Beneath this Agnolo Gaddi, again, is a small series, also attributed to Giotto, of the life of St. Francis. The scenes are the conventional ones: compare with Santa Croce: St. Francis divesting himself of his clothes and worldly goods to become the spouse of poverty: St. Peter shows Innocent III. in a dream the falling church (St. John Lateran at Rome) sustained by St. Francis: The Confirmation of the Rules of the Order. St. Francis appears in a chariot of fire (121). He descends to be present at the martyrdom of Franciscan brothers at Ceuta, etc. The scene of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata is closely similar (with its six-winged seraph and its two little churches) to the great altar-piece from San Francesco at Pisa, now preserved in the Louvre. Note its arrangement. Next it on the left, St. Francis appearing at Arles while St. Anthony of Padua is preaching, recalls the fresco in Santa Croce. Indeed, all the members of this little series may be very well collated with the frescoes of similar scenes in the Bardi Chapel. (Go also to Santa Trinità for the Ghirlandajos.)

On the end wall, 129, is an altar-piece of the Coronation of the Virgin, with attendant saints. All are named on the frame; so are the painters. Observe the saints and their symbols — especially Santa Felicità, for whose convent it was painted. Notice also the usual group of angels playing musical instruments, who develop later into such beautiful accessories. It may be worth while to note that these early altar-pieces give types for the faces of the apostles and saints which can afterward be employed to elucidate works of the Renaissance, especially Last Suppers. Left panel, Spinello: centre, Lorenzo: right, Niccolò.

To the right of the door are two stories from the life of St. Nicholas of Bari. In the upper one, he appears in the sky to resuscitate a dead child, where the double figure, dead and living, is characteristic. For the legends in full you must see Mrs. Jameson.

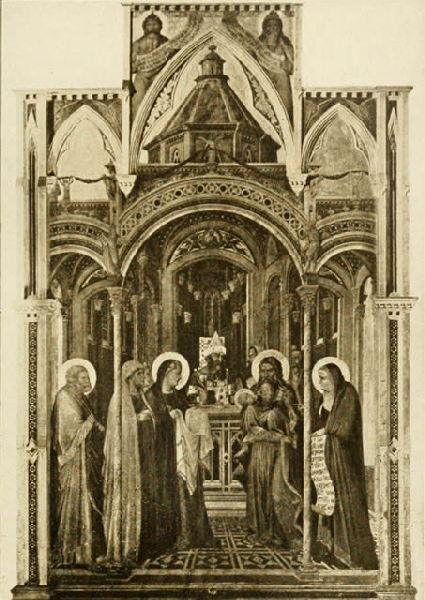

In 134, the Presentation in the Temple, by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (one of the best of the early School of Siena), note the positions of St. John and the Madonna, St. Simeon and St. Anne, whose names are legibly inscribed on their haloes. Observe also the architecture of the temple, and note that in early pictures churches and other buildings are represented as interiors by the simple device of removing one side, exactly as in a doll’s house.

LORENZETTI. — PRESENTATION IN THE TEMPLE.

All the early altar-pieces on this wall deserve attention. Do not omit St. Nicholas of Bari throwing the three purses as a dowry into the window of the poor nobleman with three starving daughters. One is already thrown and being presented: the saint is holding the other two. St. Nicholas was the patron saint of pawnbrokers (they “freely lend to all the poor who leave a pledge behind”), hence his three golden balls are the badge of that trade.

Number 137 represents the Annunciation, with saints, among whom St. John of Florence and St. Dominic are conspicuous. All are named on the frame, and should be separately identified. The wall behind the Madonna and angel, the curtain, and the bedroom in the background, are all conventional. Notice the frequent peacocks’ wings given to Gabriel. Observe, in the predella, Pope Gregory the Great, with the dove whispering at his ear as always. I do not particularise in these altar-pieces, because, as a rule, the names of the saints are marked, and all you require is the time to study them. The longer you look, the better will you understand Italian art in general.

The next picture, 139, shows itself doubly to be a Franciscan and a Florentine picture. It has the Medici saint, St. Lawrence, beside the Florentine St. John the Baptist; while on the other side stand St. Francis and St. Stephen, the latter, as often, with the stones of his martyrdom on his head, and in the rich dress of a deacon. The donor was probably a Catherine, because (though it was painted for a Franciscan convent of Santa Chiara, as the inscription states) at the Madonna’s side stand St. Catherine of Siena, the Dominican nun, and St. Catherine of Alexandria, the princess, with her wheel. In the predella, observe the Adoration of the Magi, where attitudes, camels, and other details, lead up in many ways to later treatments.

Number 140 is a characteristic Holy Trinity, with St. Romuald the Abbot and St. Andrew the Apostle. The chief subject of the predella is the Temptation of St. Anthony. In another predella, below it, notice the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple and the Marriage of the Virgin, all the elements in which should be closely compared with the frescoes at Santa Croce.

Number 143 is an Annunciation, by Don Lorenzo Monaco, where the floating angel, just alighting on his errand, and the shrinking Madonna, represent an alternative treatment of the subject from that in Neri di Bicci. Look out in future for these floating Gabriels. Note that while no marked division here exists between Gabriel and Our Lady, the two figures are yet isolated in separate compartments of the tabernacle. The saints are named. St. Proculus shows this work to have been probably painted for a citizen of Bologna, of which town he is patron, though it comes here direct from the Badia in Florence.

Number 147 introduces us to a different world. It was usual in mediæval Florence to give a bride a chest to hold her trousseau, and the fronts of such chests were often painted. This example represents a marriage between the Adimari and Ricasoli families, and is interesting from the point of view of costume and fashion. The loggia is that of the Adimari family.

The Neri di Bicci, 148, uninteresting as art, has curious types of St. Mary Magdalen, St. Margaret, St. Agnes, and St. Catherine, each with her symbol. These insipid saints have little but their symbolical significance to recommend them; yet they deserve attention as leading up to later representations.

On the window wall, notice 155, a picture which seems to lead up to or reflect the manner of Botticelli.

Near the door, 164, a Luca Signorelli is not a pleasing example of the great master. The Archangel St. Michael, weighing souls, and Gabriel bearing the lily of the Annunciation, are the best elements. The Child is also well painted, and the faces of St. Ambrose and St. Athanasius below are full of character.

The next room, the Sala Seconda, is chiefly interesting as containing, on an easel in the centre, * *Ghirlandajo’s magnificent Adoration of the Shepherds. In its wealth of detail and allusiveness, its classical touches and architecture, its triumphal arch, its sarcophagus, etc., this is a typical Renaissance work. As commonly happens with Ghirlandajo, the shepherds are clearly portraits, and admirable portraits, of contemporary Florentines. Notice the beautiful iris on the right representing the Florentine lily, also the goldfinch, close to the Divine Child, and Joseph’s saddle to the left. The distance represents the Approach of the Magi, and may be well compared with the Gentile da Fabriano. Note how the Oriental character of the head-dress survives. The landscape, though a little hard, is fine and realistic. The contrast between the ruined temple and the rough shed built over it is very graphic. Not a detail of the technique should be left unnoticed. Observe, for example, the exquisite painting of the kneeling shepherd’s woollen cap, and the straws and thatch throughout the picture. The Madonna is characteristic of the Florentine ideal of Ghirlandajo’s period. The ox and ass, on the other hand, are a little unworthy of so great an artist.

On the walls of this room are pictures, mostly of secondary interest, belonging to the age of the High Renaissance. To the right of the door are a series of good heads by Fra Bartolommeo, the best of which is that of St. Dominic, with his finger to his lips, to enforce the Dominican rule of silence.

Above them, a fine Madonna and Child by Mariotto Albertinelli, where the figures of St. Dominic with his lily, St. Nicholas of Bari with his three golden balls, and the ascetic St. Jerome with his cardinal’s hat and lion, will now be familiar. But the finest figure is that with a sword, to the left, representing St. Julian, the patron saint of Rimini. The fly-away little angels and the unhappy canopy foreshadow the decadence.

Better far is Mariotto’s Annunciation, adjacent, where the addition of the heavenly choir above is a novel feature. The shrinking position of the Madonna may well be compared with the earlier specimens, and with the beautiful Andrea del Sarto in the Uffizi.

Beyond, 171 and 173, are two Madonnas by Fra Bartolommeo, which may be taken as typical specimens of his style in fresco. Compare with the heads to the left in order to form your conception of this great but ill-advised painter, who led the way to so much of the decadence.

Between them is 172, also by Fra Bartolommeo: Savonarola in the character of St. Peter Martyr, a forcible but singularly unpleasant portrait.

Above it, 170, Fra Paolino, Madonna and Child with saints, is interesting as showing the grouping that came in with the High Renaissance, and the transformation effected in the character of the symbols. These canopied thrones belong to the age of Fra Bartolommeo. The Magdalen can only be known by her box of ointment. St. Catherine of Siena, to whom the infant Christ extends a hand, seems to be painted just for the sake of her drapery. St. Dominic with his lily becomes an insipid monk, and even the ascetic face of St. Bernardino of Siena almost loses its distinctive beauty. The attitude of St. Anthony of Padua, pointing with his hand in order to call St. Catherine’s attention to what is happening, as though she were likely to overlook it, is in the vilest taste. Altogether, a sad falling off from the purity and spirituality of the three great rooms of Botticelli and Perugino. This picture comes from the convent of Santa Caterina in Florence.

Number 174, the Madonna letting drop the Sacra Cintola to St. Thomas, is a far more pleasing specimen of Fra Paolino. The kneeling Thomas has dignity and beauty, and is not entirely painted for the sake of his feet. St. Francis is a sufficiently commonplace monk, but St. John the Baptist has not wholly lost his earlier beauty. The tomb full of lilies is pleasingly rendered, and the figures of St. Elizabeth of Hungary (or is it St. Rose?) and St. Ursula with her arrow behind have simplicity and dignity. This is of course a Franciscan picture: it comes from the convent of St. Ursula in Florence. The little frieze of saints by Michele Ghirlandajo, beneath it, is worthy of notice. The second of the series is Santa Reparata.

The other pictures in this room can, I think, be sufficiently interpreted by the reader in person.

Number 177 is by Sogliani, the angel Raphael, with Tobias and the fish. As the angel carries the sacred remedy, this was probably a blindness ex voto. To the left is St. Augustine.

The Pietà, above, by Fra Bartolommeo and Fra Paolino, is noticeable for its Dominican saints. You will know them by this time.

A second group of the Madonna letting drop her girdle to St. Thomas, by Sogliani, may be instructively compared with Fra Paolino.

The late Renaissance pictures on the rest of the wall need little comment. The Sala Terza contains works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, mostly as unpleasant as theatrical gesture and false taste can make them.

CARLO DOLCI. — ETERNAL FATHER.

Number 198, Alessandro Allori’s Annunciation, while preserving many of the traditional features, is yet a noble and valuable monument of absolute vulgarity. The fly-away Gabriel, with coarsely painted lily, the cloud on which he rests in defiance of gravitation, the cherubs behind, the third-rate actress who represents Our Lady, the roses on the floor, and the attitudes of the hands in both the chief characters, are as vile as Allori could make them. But the crowning point of bad taste in this picture is surely the eldest of the boy-angels, just out of school, and apparently sprawling in ambush on a cloud to play some practical joke on an unseen person. Comparison of this hateful Annunciation with the purity and simplicity of Fra Angelico’s at San Marco will give you a measure of the degradation of sacred art under the later Medici.

Number 203, Carlo Dolci’s Eternal Father, may be taken as in another way a splendid specimen of false sentiment and bad colouring.

Number 205, Cigoli’s St. Francis, admirably illustrates the attempt on the part of an artist who does not feel to express feeling.

Most of these pictures deserve some notice because, as foils to the earlier works, they excellently exhibit the chief faults to be avoided in painting. Sit in front of them, and then look through the open door at the great Ghirlandajo, if you wish to measure the distance that separates the fifteenth from the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Cigoli’s Martyrdom of Stephen, however, has rather more merit both in drawing and colouring; and one or two of the other pictures in the room just serve to redeem it from utter nothingness. Such as they are, the reader will now be able to understand them for himself without further description.