THE RESIDUUM.

And what a residuum! I have mentioned above what seem to me on the whole the most important objects in Florence for a visitor whose time is limited to see; but I do not by any means intend to imply that the list is exhaustive. On the contrary, I have not yet alluded to two groups of objects of the highest interest, which ought, on purely æsthetic grounds, to rank in the first order among the sights of Florence — the Medici Tombs, by Michael Angelo, in the New Sacristy at San Lorenzo; and the famous Frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel, by Masolino, Masaccio, and Filippino Lippi. For I believe it is best for the tourist to delay visiting them till he has assimilated the objects already described; and I hasten now to fill up the deficiency.

A visit should be undertaken to San Lorenzo and the Medici Tombs together. Go first to the church, and afterward to the Sacristy.

Set out by the Cathedral and the Via Cavour. Turn to the left, by the Medici (Riccardi) Palace, down the Via Gori. Diagonally opposite it, in the little Piazza, is the church of San Lorenzo, the façade unfinished. Recollect that this is the Medici church, close to the Medici palace, and that it is dedicated to the Medici saint, Lorenzo or Lawrence, patron of the Magnificent. In origin, this is one of the oldest churches in Florence (founded 390, consecrated by St. Ambrose 393); but it was burned down in 1423, and reërected by Lorenzo the elder after designs by Brunelleschi. In form, it is a basilica with flat-covered nave and vaulted aisles, ended by a transept. Note the architrave over the columns, supporting the arches. The inner façade is by Michael Angelo.

DONATELLO. — BUST OF ST. LAWRENCE.

Walk straight up the nave to the two pulpits, to right and left, by Donatello and his pupils. The right pulpit has reliefs representing Christ in Hades, Resurrection, Ascension; at the back, St. Luke between the Buffeting and the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence. The left pulpit has a Crucifixion and Deposition; at the back, St. John, between the Scourging and the Agony in the Garden; at the ends, an Entombment, Christ before Pilate, Christ before Caiaphas. In the right transept is an altar with a fine *marble tabernacle by Desiderio da Settignano. Near the steps of the choir is the plain tomb of Cosimo Pater Patriæ.

In the left transept a door leads to the old Sacristy, by Brunelleschi: note its fine architecture and proportions. Everything in it refers either to St. Lawrence or to the Medici family. Above the left door are statues of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence (buried in the same grave), with their symbols, by Donatello. Above the right door stand statues of the Medici Patrons, Cosimo and Damian, with their symbols, also by Donatello. On the left wall is a beautiful terra-cotta bust of St. Lawrence by the same; above it, coloured relief of Cosimo Pater Patriæ. On the ceiling, in the arches, are the Four Evangelists with their Beasts; on the spandrels, scenes from the Life of John the Baptist, Patron of Florence, all in stucco, by Donatello; round the room, a pretty frieze of cherubs. Among the interesting pictures, notice, on the entrance wall, St. Lawrence enthroned between his brother deacons, St. Stephen (with the stones) and St. Vincent (with the fetters), an inferior work of the School of Perugino. Several others refer to the same saints. On the bronze doors (by Donatello) are saints in pairs, too numerous to specify, but now easily identifiable; on the left door, top, observe St. Stephen and St. Lawrence. In the little room to which this door gives access is a fountain by Verrocchio, with the Medici balls; also, a modern relief of the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence. In the centre of the Sacristy itself, as you return, hidden by a table, is the marble monument of Giovanni de’ Medici and his wife, the parents of Cosimo Pater Patriæ, by Donatello. To the left of the entrance is the monument of Piero de’ Medici, son of Cosimo and father of Lorenzo, with his brother Giovanni, by Verrocchio.

Return to the church. On your right, in the left transept, as you emerge, is an *Annunciation by Filippo Lippi, with characteristic angels. In the left aisle is a large and ugly fresco of the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, by Bronzino, who uses it mainly as an excuse for some more of his very unpleasant nudes, wholly unsuited to a sacred building. Near it is a *singing-loft by Donatello and his pupils, recalling the architectural portion of his singing-loft in the Opera del Duomo. The church contains many other interesting pictures; among them, a Rosso, Marriage of the Virgin (second chapel on the right), and a modern altar-piece with St. Lawrence, marked by the gridiron embroidered on his vestments.

The cloisters and the adjoining library are also worth notice.

But the main object of artistic interest at San Lorenzo is, of course, the New Sacristy, with the famous Tombs of the Medici, by Michael Angelo.

To reach them, quit the church, and turn to the left into the little Piazza Madonna. (The Sacristy has been secularised, and is a national monument.) An inscription over the door tells you where to enter.

The steps to the Sacristy are to the left, unnoticeable. Mount them to the Cappella dei Principi, well proportioned, but vulgarly decorated in the usual gaudy taste of reigning families for mere preciousness of material. It was designed by Giovanni de’ Medici, and built in 1604. Granite sarcophagi contain the bodies of the grand-ducal family. The mosaics of the wall are costly and ugly.

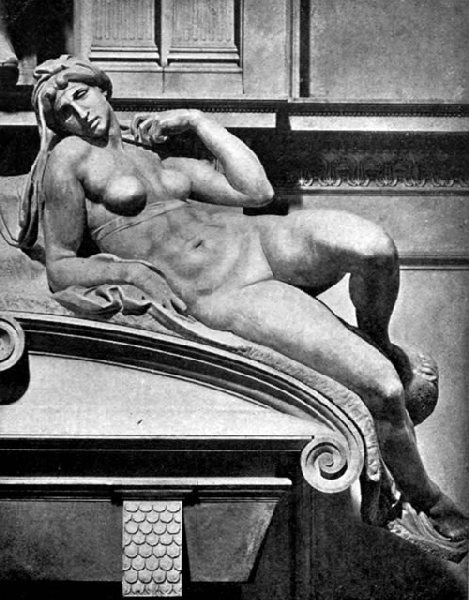

A door to the left leads along a passage to the New Sacristy, containing the * *Medici Tombs, probably the finest work of Michael Angelo, who also designed the building. To the right is the monument of Giuliano de’ Medici, Duc de Nemours, representing him as a commander; on the sarcophagus, famous figures of *Day and * *Night, very noble pieces of sculpture. To the left is the monument of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, represented in profound thought; on the sarcophagus, figures of *Evening and * *Dawn, equally beautiful. There is nothing, however, to explain in these splendid (unfinished) works, which I therefore leave to your own consideration. The other monuments which were to have filled the Sacristy were never executed.

MICHAEL ANGELO. — DAWN (DETAIL OF MONUMENT OF LORENZO DE’ MEDICI).

It is generally admitted that close inspection of the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel in the Carmelite church (Carmine) on the other side of the Arno, is indispensable to a right comprehension of the origin and development of Renaissance painting. Here first the Giottesque gives way to nascent realism. If possible, read up the admirable account in Layard’s Kugler before you go, and after you come back. Also, read in Mrs. Jameson the story of Petronilla, under St. Peter. These brief notes are only meant to be consulted on the spot, in front of the pictures.

Cross the Ponte Santa Trinità to Santa Maria del Carmine — the church of Filippo Lippi’s monastery. It was burnt down in 1771, and entirely rebuilt, so that most of it need not detain you. But the Brancacci Chapel in the right transept survived, with its famous frescoes. These were painted about 1423 and following years by Masolino and his pupil Masaccio, and completed in 1484 by Filippino Lippi. The earlier works mark time for the Renaissance. Many of the scenes contain several distinct episodes combined into one picture.

By the right pillar, above, is a Masolino, Adam and Eve in Paradise; first beginnings of the naturalistic nude; somewhat stiff and unidealised, but by no means without dawning grace and beauty. By the left pillar, above, is a Masaccio, Adam and Eve driven from Eden; far finer treatment of the nude; better modelled and more beautiful. By the left pillar, below, — I have my reasons for this eccentric order, — is a Filippino Lippi, St. Paul visits St. Peter in prison. On the right pillar, below, is a Lippi again, an angel delivers St. Peter from prison.

On the right wall, above, in a picture by Masolino, St. Peter restores Tabitha to life (or, much more probably, the Cure of Petronilla, St. Peter’s invalid daughter — a curious and repulsive legend, for which see Mrs. Jameson); and, still in the same picture, on the left, is the Healing of the Cripple at the Beautiful Gate. Masolino can be readily detected by the long and slender proportions of his figures, by his treatment of drapery, and often (even for the merest novice) by his peculiar capes and head-dresses. On the right wall, below, is a Lippi, the Martyrdom of St. Peter, also in two scenes; to the left are St. Peter and St. Paul before the Roman tribunal; to the right is the Crucifixion of St. Peter.

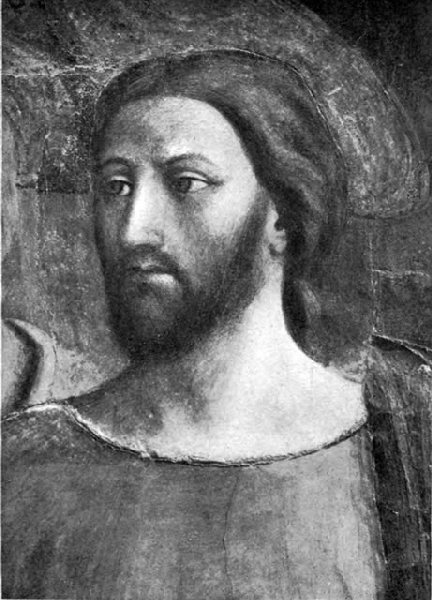

MASACCIO. — HEAD OF CHRIST (DETAIL OF TRIBUTE MONEY).

On the left wall, above, is a Masaccio, subject, the Tribute Money, in three successive scenes; in the centre, the tax-gatherer demands the tax of Christ, who sends Peter to obtain it; on the left, Peter catches the fish with the “penny” in its mouth; on the right he gives it to the tax-gatherer. Notice the everyday Florentine costume of the latter, as contrasted with the flowing robes of Christ and the Apostles, borrowed from earlier Giottesque precedent (though, of course, with immense improvement in the treatment), and handed on later to Filippino Lippi, Fra Bartolommeo, and Raphael. On the left wall, below, are frescoes partly by Masaccio, partly by Filippino Lippi (Layard and Eastlake), with a double subject; in the centre and to the left, Simon Magus challenges the Apostles to raise a dead youth to life; they accept; Simon tries, and fails; St. Peter and St. Paul succeed; from the Golden Legend: then, to the right, is the Homage paid to Peter, as in the Landini of the Uffizi. The five figures nearly in the centre, and the ten figures about the kneeling naked boy are attributed to Filippino; the rest, to Masaccio. Try to recognise their different hands in them.

On the left side of the altar wall, above, is a Masolino, the Preaching of St. Peter; below, a Masaccio, the Shadow of Peter (accompanied by John) curing the sick and deformed. On the right side, above, is a fresco by Masaccio of St. Peter Baptising (famous nude, an epoch in art), below, a Masaccio, St. Peter and St. John distributing alms; at their feet, probably, the dead body of Ananias.

Thoroughly to understand these frescoes, you should previously have seen Masolino’s work at Castiglione d’Olona (best visited from Varese). But, in any case, if you compare Masolino’s part in these paintings with previous Giottesque art, you will recognise the distinct advance in composition and figure-painting which he made on his predecessors; and if you then look at his far greater scholar, Masaccio, especially in the subject of the Tribute Money, you will observe how much progress that original genius made in anatomy, drawing, modelling, conception of the nude, realistic presentment, treatment of drapery, and feeling for landscape. Read all this subject up in Layard’s Kugler, the same evening, and then come again next day to revisit and reconsider.

The Sacristy contains a series of frescoes from the life of St. Cecilia, closely coinciding in subject with those in the Uffizi, but with a few more scenes added. I think they need no further elucidation. They have been attributed to Agnolo Gaddi or to Spinello Aretino.

In the cloister (approached by a door from the right aisle) you will find a ruined fresco by Masaccio of the Consecration of this Church; and a Madonna and Saints by Giovanni da Milano.

In order fully to understand Andrea del Sarto, and to know what height can be reached by fresco, you must go to the Annunziata.

The Church of the Santissima Annunziata, in the Piazza called after it, was originally founded in 1250, at the period when the cult of the Blessed Virgin was rapidly growing in depth and intensity throughout all Christendom. As it stands, however, it is mainly of the fifteenth to the seventeenth century. Over the central door of the three in the portico is a mosaic by Davide Ghirlandajo, with the appropriate subject of the Annunciation. The church belonged to an adjacent Servite monastery, to which the door on the left gives access.

The central door leads to an atrium, after the early fashion, with a loggia doubtless intended to represent that in which the Annunciation took place, as seen in all early pictures. It is covered with frescoes, whose unsymmetrical modern glazed arrangement sadly obscures their original order. To the left of the main entrance, facing you as you enter, is the Nativity, with the Madonna adoring the Child, by Baldovinetti, 1460. This is ruined, for it was painted on a dry wall, and has crumbled away. On the right is the arrival of the Magi, by Andrea del Sarto, a very fine work, but with less refined colour than is usual with that master. The loggia to the right has frescoes of the History of the Virgin (patroness of the church) by Andrea del Sarto and his pupils. The series begins on the inner angle, next to the Arrival of the Magi. The first is the * *Birth of the Virgin, by Andrea del Sarto, 1514; a noble work, with all the conventional features retained, St. Anne in bed, the basin, etc. The second should be the Presentation in the Temple, but was never painted. The third, the Marriage of the Virgin, by Franciabigio, 1513, is sadly damaged, but has figures recalling the motives in the Fra Angelico. The angry suitor, rejected by Perugino and Raphael, here raises his hand to strike the Joseph, as in earlier treatments. The fourth is the Visitation, by Pontormo, 1516, with the principal figures arranged as in Mariotto Albertinelli, but with no arch in the background, its place being taken by a scallop-shell niche of Renaissance architecture. The fifth, the Assumption of Our Lady, by Rosso Fiorentino, 1517, is inferior in colour and execution to the others.

The series to the left, which also begins near the inner doorway, represents incidents in the life of San Filippo Benizzi, the great saint of the Servites. In the first *San Filippo is converted, divests himself of his worldly goods and clothing, and assumes the habit of the order; compare with similar episodes in the Life of St. Francis. This is by Cosimo Rosselli; less harsh than is his wont, and with a fine treatment of the nude. In the second, by Andrea del Sarto, *San Filippo, going to Viterbo, divides his cloak with a leper, whom he cures; the Servite robes (really black, but treated as blue) lend themselves admirably to the painter’s graceful colouring. In the second, gamblers who insult San Filippo are struck by lightning; this is by Andrea. In the fourth, *a woman possessed of a devil is exorcised by San Filippo; this also by Andrea. In the fifth, by the same, *a dead child is resuscitated on touching the saint’s bier. This is a late instance of the dead and living figure being represented simultaneously in the same picture. In the sixth, children are healed of diseases by kissing his robes or relics; again by Andrea, but less pleasing in colour.

The interior of the church, with its double series of intercommunicating chapels, has been so entirely modernised and covered with gewgaws as to be uninteresting. To the left, as you enter, is the vulgarised Chapel of the Vergine Annunziata, covered with a baldacchino erected in 1448, from a design by Michelozzo, and full of ugly late silver-work. It contains, behind the altar, a miraculous thirteenth century picture of the Madonna. The last chapel but one on the left has a good Assumption of the Madonna in a mandorla, by Perugino: below are the Apostles, looking upward: the one in the centre is probably St. Thomas, but there is no Sacra Cintola. The angels are noteworthy. There is another Perugino, Madonna and Saints, in one of the Choir Chapels.

The door to the left, in the portico, outside the church, gives access to the cloisters of the Servite Monastery, with many tombs of the order and others. In a lunette opposite you as you enter, under glass, is a * *fresco of the Holy Family, by Andrea del Sarto, known as the Madonna del Sacco, and very charming. It represents the Repose on the Flight into Egypt, and takes its name from the sack of hay on which St. Joseph is seated.

At Santa Trinità the exterior is uninteresting. The interior is good and impressive Gothic; about 1250; attributed to Niccolò Pisano. In the left aisle, second chapel, is a copy of Raphael’s (Dresden) Madonna di San Sisto. In the third chapel is an Annunciation, probably by Neri di Bicci. In the fourth chapel is an altar-piece, Coronation of the Virgin, Giottesque; the saints are named on their haloes. In the fifth chapel is a lean wooden penitent Magdalen in the desert, by Desiderio da Settignano, completed by Benedetto da Majano. In the right aisle, beginning at the bottom with the first chapel, St. Maximin brings the Eucharist to St. Mary Magdalen in the Sainte Baume or cave. In the third chapel is a Giottesque Madonna and Child, with St. Andrew and St. Catherine on the left; on the right are St. Nicholas and St. Lucy. The fourth chapel, closed by a screen, contains excellent frescoes, much restored, probably by Don Lorenzo Monaco, the usual series of the History of the Virgin. On the left wall, above, is Joachim expelled from the Temple; below, Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate; on the altar wall, to the left, is the Birth of the Virgin; on the right, her Presentation in the Temple; and an altar-piece, certainly by Don Lorenzo, *Annunciation; on the right wall, below, is the Marriage of the Virgin; above, her Death. Note also the frescoes on the vaulting. This is a good place to study Don Lorenzo; compare these with the two similar earlier series by Taddeo Gaddi and Giovanni da Milano at Santa Croce. In the fifth chapel is a *marble altar by Benedetto da Rovezzano. In the transept, or, rather, the second chapel to the right, the High Altar (at the time of writing, cut off for restoration) known as the Chapel of the Sassetti, are * *frescoes from the life of St. Francis, by Domenico Ghirlandajo, 1485; subjects and grouping nearly the same as those of the Giottos in Santa Croce, with which compare these Renaissance adaptations. Begin at the upper left compartment, and read round. In the first, St. Francis quits his father’s house, and renounces his inheritance. In the second, Pope Honorius approves the Rules of the Order. In the third, St. Francis offers to undergo the Ordeal of Fire before the Sultan. The fourth represents St. Francis receiving the Stigmata; Pisa and its Campanile in the background. The fifth is a local Florentine subject; St. Francis restores to life a child of the Spini family, who had fallen from a window. The scene is in front of this very church; in the background, the Palazzo Spini (now Vieusseux’s library), and the (old) Ponte Santa Trinità. The sixth shows the death of St. Francis. Compare this fresco in particular with the Giotto, the composition of which it closely follows. As usual, Ghirlandajo introduces numerous portraits of contemporaries; if you wish to identify them, see Lafenestre. Before the altar are the donors, Francesco Sassetti and his wife, also by Ghirlandajo; note that Francis is the donor’s name-saint. On the ceiling are Sibyls. (The Adoration of the Shepherds, in the Belle Arti, by Ghirlandajo, was originally the altar-piece of this chapel.) The *tombs of the Sassetti are by Giuliano da Sangallo.

Florence is so inexhaustible that for the other churches I can only give a few brief hints, which the reader who has followed me so far will now, I hope, be in a position to fill in for himself.

Santo Spirito is an Augustinian church, attached to a monastery. It has thirty-eight chapels, almost all with good altar-pieces; the interior is vast and impressive; mainly by Brunelleschi. St. Nicholas is here a locally important saint. (A neighbouring parish is San Niccolò.) The most remarkable pictures among many are, the fifth chapel (beginning from the right aisle), for a *Madonna with St. Nicholas and St. Catherine, by Filippino Lippi; and the twenty-ninth chapel, for a * *masterpiece of an unknown artist, the Trinity with St. Catherine and the penitent Magdalen, — a most striking work, remarkable for its ascetic and morbid beauty. For the rest, you must be content with Baedeker, or follow Lafenestre. Notice the good cloisters.

FILIPPINO LIPPI. — MADONNA APPEARING TO ST. BERNARD.

The Ognissanti is a Franciscan church, also attached to a monastery. It is dedicated to All Saints; hence the character of the group in the Giovanni della Robbia which fills the lunette over the doorway. Its best pictures are a *St. Augustine by Botticelli, and a *St. Jerome by Domenico Ghirlandajo, — two doctors of the Church, the other two never finished, — on the right and left of the nave. The cloisters have frescoes from the life of St. Francis and Franciscan saints. The Refectory I will notice later.

The Badia, opposite the Bargello, should be visited, by those who have time, for the sake of the glorious Filippino Lippi of the * *Madonna appearing to St. Bernard, one of his earliest works, and perhaps his finest. It has also some beautiful tombs by Mino da Fiesole; St. Leonard with the fetters in one of them will by this time be familiar.

San Felice, San Niccolò, etc., you need only visit when you have thoroughly seen everything else in Florence.

Among minor sights I must lump not a few works of very high value.

A comparative study of the various representations of the Cenacolo (or Last Supper), usually in Refectories of suppressed monasteries, is very interesting. We have already seen those at Santa Croce (Giottesque) and at San Marco (Ghirlandajo). There is a second Ghirlandajo, almost a replica, in the Refectory of the Ognissanti; a notice marks the door, just beyond the church. The Franciscans wanted to have as good a picture as their Dominican brethren. The room contains several other interesting works both in painting and sculpture. A far more lovely Last Supper is that known as the *Cenacolo di Fuligno, in the Via Faenza; notice on the door. It occupies the end wall of the Refectory of the old monastery of Sant’Onofrio, and belongs to the School of Perugino. It was once attributed to Raphael, and more lately has been assigned to Gerino da Pistoja; if so, it is by many stages his finest work. Whoever painted it, however, it is one of the most beautiful things in Florence. Yet another Last Supper is to be found in the Refectory of the old Convent of Sant’Apollonia in the street of the same name; it is by Andrea del Castagno, a large number of whose other works have lately been transferred hither, so that this little museum offers the best opportunity of studying that able and vigorous but harsh and soulless master. See also the *Andrea del Sarto at San Salvi. I advise a visit to these four little shows in close succession. Read Mrs. Jameson on the subject beforehand, or take her with you.

If possible walk one day through the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, founded by Folco Portinari (father of Dante’s Beatrice), and full of memories of the Portinari family. Then, visit the little picture gallery of the Hospital. It contains many objects of interest, and two masterpieces. One is a * *triptych by Hugo van der Goes, the Flemish painter, produced for Tommaso Portinari, agent of the Medici at Bruges, and brought by him to Florence; it is doubtless the finest Flemish work in the city. In the centre is the Nativity, with St. Joseph (?) and adoring shepherds, as well as charming angels, and some exquisite irises. Every straw, every columbine, every vase in his admirable work should be minutely noticed. In the left wing, are the donor’s wife and daughter, presented by their patron saints, St. Mary Magdalen, with her alabaster box, and St. Margaret, with her dragon; on the right wing, the donor and his two sons, presented by St. Matthew (?) and St. Anthony Abbot. This work deserves long and attentive study. In the next room is a *Last Judgment, by Fra Bartolommeo and Mariotto Albertinelli, much damaged, but important as a link in a long chain of similar subjects. See in this connection the great fresco in the Campo Santo at Pisa, the one at Santa Maria Novella, by Orcagna, the panel here, to collate with it, and finally Michael Angelo’s marvellous modernisation in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, which takes many points from this and the earlier representations. The rooms also contain several other interesting pictures.

ANDREA DELLA ROBBIA. — A BABY.

The Chapter-house of the Convent of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi (a local saint, belonging to the Pazzi family; see Santa Croce), contains a noble * *Crucifixion by Perugino, one of the finest single pictures in Florence. It is in three compartments. In the centre is a Crucifixion, with Mary Magdalen, kneeling; left and right are the Madonna and St. John, standing; and St. Bernard and St. Benedict kneeling. The remarkable abstractness and isolation of Perugino’s figures is nowhere more observable; it comes out even in the three trees of the left background.

The Spedale degli Innocenti, or Foundling Hospital, near the Annunziata, should be visited both for its charming babies, by Andrea della Robbia, and for its beautiful * *altar-piece of the Adoration of the Magi, with St. John the Baptist of Florence presenting two of the massacred Innocents, by Domenico Ghirlandajo. This is a lovely and appropriate picture, the full meaning of which you will now be in a position to understand. (The church is dedicated to the Holy Innocents.) The lovely landscape and accessories need no bush. In the background, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Announcement to the Shepherds, etc. A masterpiece to study.

For everything else within the town, I must hand you over to Baedeker, Hare, Miss Horner, and Lafenestre.

A stray afternoon may well be devoted to the queer little church of San Leonardo in Arcetri, outside the town, on the south side of the Arno. To reach it, cross the Ponte Vecchio, and take the second turn on your left, under an arch that spans the roadway. Then follow the steep paved way of the Via della Costa San Giorgio (which will probably reveal to you an unexpected side of Florence). The Porta San Giorgio, which pierces the old walls at the top, has a fresco of the Madonna, between St. George and St. Leonard, the latter bearing the fetters which are his usual symbol; on its outer face is a good relief of St. George and the Dragon. (Note relevancy to the parishes of San Giorgio, below, and San Leonardo, above it.) Follow the road straight to the little church of San Leonardo on your left. (If closed, ring at the door of the cottage in the garden to the right of its façade.)

The chief object of interest within is the pulpit, with rude reliefs of the twelfth century, said to be the oldest surviving pulpit carvings, brought hither from San Pietro Scheraggio, near the Palazzo Vecchio. It has been suggested that these quaint old works gave hints to Niccolò Pisano for his famous and beautiful pulpit in the Baptistery at Pisa. But it must also be remembered, first, that these subjects already show every trace of being conventionalised, so that in all probability many such pulpits once existed, of which Niccolò’s is only the finest artistic outcome; and, second, that the figure here which most suggests (or rather foreshadows) Niccolò (the recumbent Madonna in the Nativity) is the analogue of the very one in which that extraordinary genius most closely imitated an antique model in the Campo Santo at Pisa. We may, therefore, conclude that Niccolò merely adopted a conventional series, common at this time, of which this is an early and inferior example, but that he marvellously vivified it by quasi-antique treatment of the faces, figures, draperies, and attitudes, at the same time that he immensely enriched the composition after the example of the antique sarcophagi. The series as it at present exists on this pulpit is out of chronological order, doubtless owing to incorrect putting together at the transference hither. The scenes are, from left to right, the Presentation in the Temple; the Baptism of Christ; the Adoration of the Magi; the Madonna rising from the stem of Jesse; the Deposition from the Cross; and the Nativity. All should be closely observed as early embodiments of the scenes they represent.

Among the older pictures in the church, the most interesting are, on the same wall, the Madonna dropping the Sacra Cintola to St. Thomas, attended by St. Peter, St. Jerome, etc.; and, on the opposite wall, Madonna with St. Leonard (holding the fetters) and other saints readily recognised.

You can vary the walk, on your return, by diverging just outside the gate and following the path which leads along the old walls, with delicious glimpses across the ravine toward the Piazzale, and reëntering the town at Porta San Miniato.

I am always grateful to a book, however inadequate, which has taught me something. Nobody could be more aware than its author of the shortcomings of this one. I shall be content if my readers find, among many faults, that it has helped to teach them how to see Florence. Others may know Florence more intimately: no one could love it better.

THE END