Fig. 43. — Common Cinquefoil.

Although the roses, like many other highly respectable modern families, cannot claim for themselves any remarkable antiquity — their tribe is only known, with certainty, to date back some three or four millions of years, to the tertiary period of geology — they have yet in many respects one of the most interesting and instructive histories among all the annals of English plants. In a comparatively short space of time they have managed to assume the most varied forms; and their numerous transformations are well attested for us by the great diversity of their existing representatives. Some of them have produced extremely beautiful and showy flowers, as is the case with the cultivated roses of our gardens, as well as with the dog-roses, the sweet-briars, the may, the blackthorn, and the meadow-sweet of our hedges, our copses, and our open fields. Others have developed edible fruits, like the pear, the apple, the apricot, the peach, the nectarine, the cherry, the strawberry, the raspberry, and the plum; while yet others again, which are less serviceable to lordly man, supply the woodland birds or even the village children with blackberries, dewberries, cloudberries, hips, haws, sloes, crab-apples, and rowanberries. Moreover, the various members of the rose family exhibit almost every variety of size and habit, from the creeping silver-weed which covers our roadsides or the tiny alchemilla which peeps out from the crannies of our walls, through the herb-like meadow-sweet, the scrambling briars, the shrubby hawthorn, and the bushy bird-cherry, to the taller and more arborescent forms of the apple-tree, the pear-tree, and the mountain ash. And since modern science teaches us that all these very divergent plants are ultimately descended from a single common ancestor — the primæval progenitor of the entire rose tribe — whence they have gradually branched off in various directions, owing to separately slight modifications of structure and habit, it is clear that the history of the roses must really be one of great interest and significance from the new standpoint of evolution. I propose, therefore, here to examine the origin and development of the existing English roses, with as little technical detail as possible; and I shall refer for the most part only to those common and familiar forms which, like the apple, the strawberry, or the cabbage rose, are already presumably old acquaintances of all my readers.

The method of our inquiry must be a strictly genealogical one. For example, if we ask at the present day whence came our own eatable garden plums, competent botanists will tell us that they are a highly cultivated and carefully selected variety of the common sloe or blackthorn. It is true, the sloe is a small, sour, and almost uneatable fruit, the bush on which it grows is short and trunkless, and its branches are thickly covered with very sharp stout thorns; whereas the cultivated plum is borne upon a shapely spreading tree, with no thorns, and a well-marked trunk, while the fruit itself is much larger, sweeter, and more brightly coloured than the ancestral sloe. But these changes have easily been produced by long tillage and constant selection of the best fruiters through many ages of human agriculture. So, again, if we ask what is the origin of our pretty old-fashioned Scotch roses, the botanists will tell us in like manner that they are double varieties of the wild burnet-rose which grows beside the long tidal lochs of the Scotch Highlands, or clambers over the heathy cliffs of Cumberland and Yorkshire. The wild form of the burnet-rose has only five simple petals, like our own common sweet-briar; but all wild flowers when carefully planted in a rich soil show a tendency to double their petals; and, by selecting for many generations those burnet-roses which showed this doubling tendency in the highest degree, our florists have at last succeeded in producing the pretty Scotch roses which may still be found (thank Heaven!) in many quiet cottage gardens, though ousted from fashionable society by the Marshal Niels and Gloires de Dijon of modern scientific horticulturists.

Now, if we push our inquiry a step further back, we shall find that this which is true of cultivated plants in their descent from wild parent stocks, is true also of the parent stocks themselves in their descent from an earlier common ancestor. Each of them has been produced by the selective action of nature, which has favoured certain individuals in the struggle for existence, at the expense of others, and has thus finally resulted in the establishment of new species, having peculiar points of advantage of their own, now wholly distinct from the original species whose descendants they are. Looked at in this manner, every family of plants or animals becomes a sort of puzzle for our ingenuity, as we can to some extent reconstruct the family genealogy by noting in what points the various members resemble one another, and in what points they differ among themselves. To discover the relationship of the various English members of the rose tribe to each other — their varying degrees of cousinship or of remoter community of descent — is the object which we set before ourselves in the present paper.

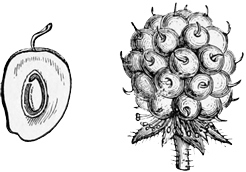

Perhaps the simplest and earliest type of the rose family now remaining in England is to be found in the little yellow potentillas which grow abundantly in ill-kept fields or by scrubby roadsides. The potentillas are less familiar to us than most others of the rose family, and therefore I am sorry that I am obliged to begin by introducing them first to my reader’s notice rather than some other and older acquaintance, like the pear or the hawthorn. But as they form the most central typical specimen of the rose tribe which we now possess in England, it is almost necessary to start our description with them, just as in tracing a family pedigree we must set out from the earliest recognisable ancestor, even though he may be far less eminent and less well-known than many of his later descendants. For to a form very much like the potentillas all the rose family trace their descent. The two best known species of potentilla are the goose-weed or silver-weed, and the cinquefoil. Both of them are low creeping herb-like weeds, with simple bright yellow blossoms about the size of a strawberry flower, having each five golden petals, and bearing a number of small dry brown seeds on a long green stalk. At first sight a casual observer would hardly take them for roses at all, but a closer view would show that they resemble in all essential particulars an old-fashioned single yellow rose in miniature. From some such small creeping plants as these all the roses are probably descended. Observe, I do not say that they are the direct offspring of the potentillas, but merely that they are the offspring of some very similar simple form. We ourselves do not derive our origin from the Icelanders; but the Icelanders keep closer than any other existing people to that primitive Teutonic and Scandinavian stock from which we and all the other people of northwestern Europe are descended. Just so, the roses do not necessarily derive their origin from the potentillas, but the potentillas keep closer than any other existing rose to that primitive rosaceous stock from which all the other members of the family are descended.

The strawberry is one of the more developed plants which has varied least from this early type represented by the cinquefoil and the silver-weed. There is, in fact, one common English potentilla, whose nature we have already considered, and which bears with village children the essentially correct and suggestive name of barren strawberry. This particular potentilla differs from most others of its class in having white petals instead of yellow ones, and in having three leaflets on each stalk instead of five or seven. When it is in flower only it is difficult at first sight to distinguish it from the strawberry blossom, though the petals are generally smaller, and the whole flower less widely opened. After blossoming, however, the green bed or receptacle on which the little seeds are seated does not swell out (as in the true strawberry) into a sweet, pulpy, red mass, but remains a mere dry stalk for the tiny bunch of small hard inedible nuts. The barren strawberry, indeed, as we saw in an earlier paper, is really an intermediate stage between the other potentillas and the true eatable strawberry; or, to put it more correctly, the eatable strawberry is a white-flowered potentilla which has acquired the habit of producing a sweet and bright-coloured fruit instead of a few small dry seeds. Since we have got to understand the rationale of this first and simplest transformation, we have now a clue by which we may interpret almost all the subsequent modifications of the rose family, and I must therefore be permitted here briefly to recapitulate the chief points we have already proved in this matter.

The true strawberry, we saw, resembles the barren strawberry in every particular except in its fruit. It is a mere slightly divergent variety of that particular species of potentilla, though the great importance of the variety from man’s practical point of view causes us to give it a separate name, and has even wrongly induced botanists to place it in a separate genus all by itself. In reality, however, the peculiarity of the fruit is an extremely slight one, very easily brought about. In all other points — in its root, its leaf, its stem, its flower, nay, even its silky hairs — the strawberry all but exactly reproduces the white potentilla. It is nothing more than one of these potentillas with a slight diversity in the way it forms its fruit. To account, therefore, for the strawberry we had first to account for the white potentilla from which it springs.

The white potentilla, or barren strawberry, you will remember, is itself a slightly divergent form of the yellow potentillas, such as the cinquefoil. From these it differs in three chief particulars. In the first place, it does not creep, but stands erect; this is due to its mode of life on banks or in open woods, not among grass and meadows as is the case with the straggling cinquefoil. In the second place, it has three leaflets on each stalk instead of five, and this is a slight variation of a sort liable to turn up at any time in any plant, as the number of leaflets is very seldom quite constant. In the third place, it has white petals instead of yellow ones, and this is the most important difference of any. All flowers with bright and conspicuous petals we know are fertilised by insects, which visit them in search of honey or pollen, and the use of the coloured petals is, in fact, to attract the insects and to induce them to fertilise the seeds. Now, yellow seems to have been the original colour of the petals in almost all (if not absolutely in all) families of flowers; and the greater number of potentillas are still yellow. But different flowers are visited and fertilised by different insects, and as some insects like one colour and some another, many blossoms have acquired white or pink or purple petals in the place of yellow ones, to suit the particular taste of their insect friends. In tracing the upward course of development in the roses, we shall see that they follow the ordinary law of progressive chromatic changes: the simpler types are yellow; the somewhat higher ones are white; the next pink; and the highest in this particular family are red; for no rose has yet attained to the final stage of all, which is blue. The colours of petals are always liable to vary, as we all see in our gardens, where florists can produce at will almost any shade or tint that they choose; and when wild flowers happen to vary in this way, they often get visited by some fresh kind of insect which fertilises their seeds better than the old ones did, and so in time they set up a new variety or a new species. Two of our English potentillas have thus acquired white flowers to suit their proper flies, while one boggy species has developed purple petals to meet the æsthetic requirements of the marshland insects. No doubt the white blossoms of the barren strawberry are thus due to some original ‘sport’ or accidental variation, which has been perpetuated and become a fixed habit of the plant because it gave it a better and surer chance of setting its seeds, and so of handing down its peculiarities to future generations.

And now, how did we find the true strawberry had developed from the three-leaved white potentilla? Here the birds came in to play their part, as the bees and flies had done in producing the white blossom. Birds are largely dependent upon fruits and seeds for their livelihood, and so far as they are concerned it does not matter much to them which they eat. But from the point of view of the plant it matters a great deal. For if a bird eats and digests a seed, then the seed can never grow up to be a young plant; and it has so far utterly failed of its true purpose. If, however, the fruit has a hard indigestible seed inside it (or, in the case of the strawberry, outside it), the plant is all the better for the fact, since the seed will not be destroyed by the bird, but will merely be dispersed by it, and so aided in attaining its proper growth. Thus, if certain potentillas happened ever to swell out their seed receptacle into a sweet pulpy mass, and if this mass happened to attract birds, the potentillas would gain an advantage by their new habit, and would therefore quickly develop into wild strawberries as we now get them. But the difference between the strawberry fruit and the potentilla fruit is to the last a very slight one. Both have a number of little dry seeds seated on a receptacle; only, in the strawberry the receptacle grows red and succulent, while in the potentilla it remains small and stalk-like. The red colour and sweet juice of the strawberry serve to attract the birds which aid in dispersing the seed, just as the white or yellow petals and the sweet honey of the potentilla blossoms serve to attract the insects which aid in fertilising the flowers. In this way all nature is one continual round of interaction and mutual dependence between the animal and vegetable worlds.

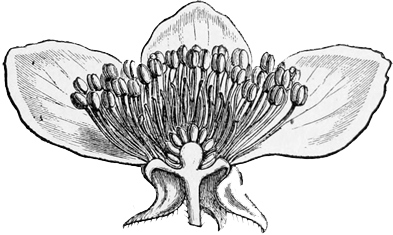

Fig. 44. — Fruit of Bramble.

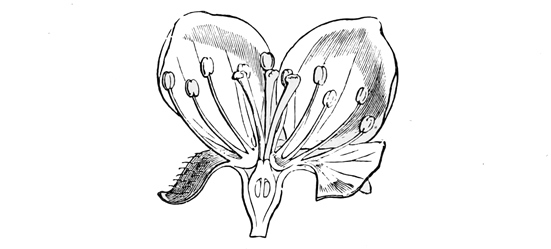

Fig. 45. — Flower of Bramble.

The potentillas and the strawberry plant are all of them mere low creeping or skulking herbs, without woody stems or other permanent branches. But when we get to the development of the brambles or blackberry bushes, we arrive at a higher and more respectable division of the rose family. There are two or three intermediate forms, such as water-avens and herb-bennet — tall, branching, weedy-looking roadside plants — which help us to bridge over the gulf from the one type to the other. Indeed, even the strawberry and the cinquefoil have a short perennial, almost woody stock, close to the ground, from which the annual branches spring; and in some other English weeds of the rose family the branches themselves are much stiffer and woodier than in these creeping plants. But in the brambles, the trunk and boughs have become really woody, by the deposit of hard material in the cells which make up their substance. Still, even the brambles are yet at heart mere creepers like the cinquefoil. They do not grow erect and upright on their own stems: they trail and skulk and twine in and out among other and taller bushes than themselves. The leaves remain very much of the cinquefoil type; and altogether there is a good deal of the potentilla left in the brambles even now.

However, these woody climbers have certainly some fresh and more developed peculiarities of their own. They are all prickly shrubs, and the origin of their prickles is sufficiently simple. Even the potentillas have usually hairs on their stems; and these hairs serve to prevent the ants and other honey-thieving insects from running up the stalks and stealing the nectar intended for fertilising bees and butterflies. Similar hairs in the goose-grass grew, you will recollect, into the little clinging hooks of the stems and midribs. But in the brambles, hairs of the same sort have grown still thicker and stouter, side by side with the general growth in woodiness of the whole plant; so that they have at last developed into short thorns, which serve to protect the leaves and stem from herbivorous animals. As a rule, the bushes and weeds which grow in waste places are very apt to be protected in some such fashion, as we see in the case of gorse, nettles, blackthorn, holly, thistles, and other plants; but the particular nature of the protection varies much from plant to plant. In the brambles it takes the form of stiff prickly hairs; in the nettles, of stinging hairs; in the gorse, of pointed leaves; and in the thorn-bushes of short, sharp, barren branches.

Another peculiarity of the bramble group is their larger white flowers and their curious granulated fruit. The flowers, of course, are larger and whiter in order to secure the visits of their proper fertilising insects; the fruits are sweet and coloured in order to attract the hedgerow birds. Observe, too, that the flowers being higher in type than those of the strawberry, are often tinged with pink: here we get the first upward step in the direction of the true roses. The nature of the fruit in the raspberry, the blackberry, and the dewberry, again, is quite different from that of the strawberry. Here, instead of the receptacle swelling out and growing red and juicy, it is the outer coat of the separate little seeds themselves that forms the eatable part; while the receptacle remains white and inedible, being the ‘hull’ or stem which we pick out from the hollow thimble-like fruit in the raspberry. Each little nut, which in the strawberry was quite hard and brown, is here covered with a juicy black or red pulp, inside which lies the stony real seed; so that a blackberry looks like a whole collection of tiny separate fruits, run together into a single head. Moreover, there are other minor differences in the berries themselves, even within the bramble group; for while the raspberry and cloudberry are red, to suit one set of birds, the blackberry and dewberry are bluish black, to suit another set; and while the little grains hold together as a cup in the raspberry, but separate from the hull, they cling to the hull in the other kinds. Nevertheless, in leaves, flower, and fruit there is a very close fundamental agreement among all the bramble kind and the potentillas. Thus we may say that the brambles form a small minor branch of the rose family, which has first acquired a woody habit and a succulent fruit, and has then split up once more into several smaller but closely allied groups, such as the blackberries, the raspberries, the dewberries, and the stony brambles.

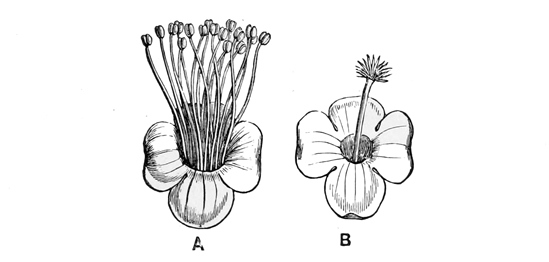

Fig. 46. — Vertical section of a Dog-rose.

The true roses, represented in England by the dog-rose and sweet-briar, show us a somewhat different development from the original type. They, too, have grown into tall bushes, less scrambling and more erect than the brambles. They have leaves of somewhat the same sort, and prickles which are similarly produced by the hardening of sharp hairs upon the stem. But their flowers and fruit are slightly more specialised — more altered, that is to say, for a particular purpose from the primitive plan. In the first place, the flowers, though still the same in general arrangement, with five petals and many stamens and carpels (or fruit-pieces), have varied a good deal in detail. The petals are here much larger, and they have advanced to the stage of a brilliant pink; while the blossoms are also sweet-scented. These peculiarities of course serve to attract the bees and other large fertilising insects, which thus carry pollen from head to head, and aid in setting the seeds much more securely than the little pilfering flies. Moreover, in all the roses, the outer green cup which covers the blossom in the bud has grown up around the little seeds or fruit-pieces, so that instead of a ball turned outward, as in the strawberry and raspberry, you get, as it were, a bottle turned inward, with the seeds on the inner side. After flowering, as the fruit ripens, this outer cup grows round and red, forming the hip or fruit-case, inside which are to be found the separate little hairy seeds. Birds eat this dry berry, though we do not, and thus aid in dispersing the species. But though they digest the soft red outer pulp, formed by the swollen stalk, they cannot digest the hairy seed, so the plant attains its prime object of getting them duly scattered. The true roses, then, are another branch of the original potentilla stock, which have acquired a bushy mode of growth, with a fruit differing in construction from that of the brambles. Our English kinds are merely pink; the more developed exotics are often scarlet and crimson.

We have altogether some five true wild roses in Britain. The commonest is the dog-rose, which everybody knows well; and next comes the almost equally familiar sweet-briar, with its delicately scented glandular leaves. The burnet-rose is the parent of our cultivated Scotch roses, and the two other native kinds are comparatively rare. Double garden roses are produced from the single five-petalled wild varieties by making the stamens (which are the organs for manufacturing pollen) turn into bright-coloured petals. There is always more or less of a tendency for stamens thus to alter their character; but in a wild state it never comes to any good, because such plants can never set seed, for want of pollen, and so die out in a single generation. Our gardeners, however, carefully select these distorted individuals, and so at length produce the large, handsome, barren flowers with which we are so familiar. The cabbage and moss roses are monstrous forms thus bred from the common wild French roses of the Mediterranean region; the China roses are cultivated abortions from an Asiatic species; and most of the other garden varieties are artificial crosses between these or various other kinds, obtained by fertilising the seed vessels of one bush with pollen taken from the blossoms of another of a different sort. To a botanical eye, double flowers, however large and fine, are never really beautiful, because they lack the order and symmetry which appear so conspicuously in the five petals, the clustered stamens, and the regular stigmas of the natural form.

From the great central division of the rose family, thus represented by the potentillas, the strawberry, the brambles, and the true roses, two main younger branches have diverged much more widely in different directions. As often happens, these junior offshoots have outstripped and surpassed the elder stock in many points of structure and function. The first of the two branches in question is that of the plum-tribe; the second is that of the pears and apples. Each presents us with some new and important modifications of the family traits.

Of the plum tribe, our most familiar English examples, wild or cultivated, are the sloe or blackthorn, with its descendant the garden plum; as well as the cherry, the apricot, the peach, the nectarine, and the almond. All these plants differ more or less conspicuously from the members of the central group which we have so far been examining in their tree-like size and larger trunks. But they also differ in another important point: each flower contains only one seed instead of many, and this seed is inclosed in a hard bony covering, which causes the whole plum tribe (except only the almond, of which more anon) to be popularly included under the common title of ‘stone-fruits.’ In most cases, too, the single seed is further coated with a soft, sweet, succulent pulp, making the whole into an edible fruit. What, now, is the reason for this change? What advantage did the plant derive from this departure from the ordinary type of rose-flower and rose-fruit? To answer this question we must look at one particular instance in detail, and we cannot do better than take that well-known fruit, the cherry, as our prime example of the whole class.

The cherry, like the strawberry, is an eatable fruit. But while in the strawberry we saw that the pulpy part consisted of the swollen stalk or receptacle, in which several small dry seeds were loosely embedded, with the cherry the pulpy part consists of the outer coat of the fruit or seed vessel itself, which has grown soft and juicy instead of remaining hard and dry. In this respect the cherry resembles a single grain from a raspberry; but from the raspberry, again, it differs in the fact that each flower produces only a single solitary one-seeded fruit, instead of producing a number of little fruits, all arranged together in a sort of thimble. In the raspberry flower, when blossoming, you will find in the centre several separate carpels or fruit-pieces; in the cherry you will find only one. The cherry, in fact, may (so far as its fruit is concerned) be likened to a raspberry in which all the carpels or fruit-pieces except one have become aborted. And the reason for the change is simply this: cherry bushes (for in a wild state they are hardly trees) are longer-lived plants than the bramble kind, and bear many more blossoms on each bush. Hence one seed to every blossom is quite as many as they require to keep up the numbers of the species. Moreover their large and attractive fruits are much more likely to get eaten and so dispersed by birds than the smaller and less succulent berries of the brambles. Furthermore, the cherry has a harder stone around each seed, which is thus more effectually protected against being digested, and the seed itself consists of a comparatively big kernel, richly stored with food-stuffs for the young plant, which thus starts relatively well equipped in the battle of life. For all these reasons the cherries are better off than the brambles, and therefore they can afford to produce fewer seeds to each flower, as well as to make the coverings of these seeds larger and more attractive to birds. Originally, indeed, the cherry had two kernels in each stone, and to this day it retains two little embryo kernels in the blossom, one of which is usually abortive afterwards (though even now you may sometimes find two, as in philipœna almonds); but one seed being ordinarily quite sufficient for all practical purposes, the second one has long since disappeared in the vast majority of cases.

The plum scarcely differs from the cherry in anything important except the colour, size, and shape of the fruit. It is, as we have already noted, a cultivated variety of the blackthorn, in which the bush has become a tree, the thorns have been eradicated, and the fruit has been immensely improved by careful selection. The change wrought in these two wild bushes by human tillage shows, indeed, how great is the extent to which any type of plant can be altered by circumstances in a very short time. The apricot is yet another variety of the same small group, long subjected to human cultivation in the East.

Peaches and nectarines differ from apricots mainly in their stones, which are wrinkled instead of being smooth; but otherwise they do not seriously diverge from the other members of the plum tribe. Indeed, though botanists rank the apricot as a plum, because of its smooth stone, and put the peach and nectarine in a genus by themselves, because of their wrinkled coating, common sense shows us at once that it would be much easier to turn an apricot into a peach than to turn a plum into an apricot. There is one species of nectarine, however, which has undergone a very curious change, and that is the almond. Different as they appear at first sight, the almond must really be regarded as a very slightly altered variety of nectarine. Its outer shell or husk represents the pulpy part of the nectarine fruit; and indeed, if you cut in two a young unripe almond and a young unripe nectarine, you will find that they resemble one another very closely. But as they ripen the outer coat of the nectarine grows juicier, while that of the almond grows stringier and coarser, till at last the one becomes what we commonly call a fruit, while the other becomes what we commonly call a nut. Here, again, the reason for the change is not difficult to divine. Some seeds succeed best by making themselves attractive and trusting to birds for their dispersion; others succeed best by adopting the tactics of concealment, by dressing themselves in green when on the tree, and in brown when on the ground, and by seeking rather to evade than to invite the attention of the animal world. Those seed vessels which aim at the first plan we know as fruits; those which aim rather at the second we know as nuts. The almond is just a nectarine which has gone back to the nut-producing habit. The cases are nearly analogous to those of the strawberry and the potentilla, only the strawberry is a fruit developed from a dry seed, whereas the almond is a dry seed developed from a fruit. To some extent this may be regarded as a case of retrogressive evolution or degeneration.

The second great divergent branch of the rose family — that of the pears and apples — has proceeded towards much the same end as the plums, but in a strikingly different manner. The apple kind have grown into trees, and have produced fruits. Instead, however, of the seed vessel itself becoming soft and succulent, the calyx or outer flower covering of the petals has covered up the carpels or young seed vessels even in the blossom, and has then swollen out into a sort of stalk-like fruit. The case, indeed, is again not unlike that of the strawberry, only that here the stalk has enlarged outward round the flower and inclosed the seeds, instead of simply swelling into a boss and embedding them. In the hip of the true roses we get some foreshadowing of this plan, except that in the roses the seeds still remained separate and free inside the swollen stalk, whereas in the pear and apple the entire fruit grows into a single solid mass. Here also, as before, we can trace a gradual development from the bushy to the tree-like form.

Fig. 47. — Vertical section of Apple-blossom.

The common hawthorn of our hedges shows us, perhaps, the simplest stage in the evolution of the apple tribe. It grows only into a tall bush, not unlike that of the blackthorn, and similarly armed with stout spines, which are really short sharp branches, not mere prickly hairs, as in the case of the brambles. Occasionally, however, some of the hawthorns develop into real trees, with a single stumpy trunk, though they never grow to more than mere small spreading specimens of the arboreal type, quite unlike the very tall and stately pear-tree. The flowers of the hawthorn — may-blossom, as we generally call them — are still essentially of the rose type; but, instead of having a single embryo seed and simple fruit in the centre, they have a compound fruit, inclosing many seeds, and all embedded in the thick fleshy calyx or flower-cup. As the haw ripens the flower-cup outside grows redder and juicier, and the seed pieces at the same time become hard and bony. For it is a general principle of all edible fruits that, while they are young and the seeds are unripe, they remain green and sour, because then they could only be losers if eaten by birds; but as the seeds ripen and become fit to germinate, the pulp grows soft and sweet, and the skin assumes its bright hue, because then the birds will be of service to it by diffusing the mature seeds. How largely birds assist in thus dispersing plants has very lately been proved in Australia, where a new and troublesome weed has rapidly overrun the whole country, because the fruit-eaters are very fond of it, and scatter its seeds broadcast over the length and breadth of the land.

The common medlar is nothing more than a hawthorn with a very big overgrown haw. In the wild state it bristles with hard thorns, which are wanting to the cultivated form, and its flower almost exactly resembles that of the may. The fruit, however, only becomes edible after it begins to decay, and the bony covering of the seeds is remarkably hard. It seems probable that the medlar, originally a native of southern Europe, is largely dispersed, not by birds, but by mice, rats, and other small quadrupeds. The colour is not particularly attractive, nor is the fruit particularly tempting while it remains upon the bush; but when it falls upon the ground and begins to rot, it may easily be eaten by rodents or pigs, and thus doubtless it procures the dispersion of its seeds under conditions highly favourable to their proper growth and success in life.

The little Siberian crabs, largely cultivated for their fruit in America, and sometimes found in English shrubberies as well, give us one of the earliest and simplest forms of the real apple group. In some respects, indeed, the apples are even simpler than the hawthorn, because their seeds or pips are not inclosed in bony cases, but only in those rather tough leathery coverings which form what we call the core. The haw of the hawthorn may be regarded as a very small crab-apple, in which the walls of the seed cells have become very hard and stony; or the crab may be regarded as a rather large haw, in which the cell walls still remain only thinly cartilaginous. The flowers of all the group are practically identical, except in size, and the only real difference of structure between them is in the degree of hardness attained by the seed covers. The crabs, the apples, and the pears, however, all grow into tallish trees, and so have no need for thorns or prickles, because they are not exposed to the attacks of herbivorous animals. Ordinary orchard apples are, of course, merely cultivated varieties of the common wild crabs. In shape the apple-tree is always spreading, like an arboreal hawthorn, only on a larger scale. The pear-tree differs from it in two or three small points, of which the chief are its taller and more pyramidal form, and the curious tapering outline of the fruit. Nevertheless, pear-trees may be found of every size and type, especially in the wild state, from a mere straggling bush, no bigger than a hawthorn, to a handsome towering trunk, not unlike an elm or an alder.

In the matter of fruits, the apple group are more advanced than the roses, but so far as regards the flower alone, viewed as an organ for attracting insects, many of the apple tribe are inferior to the true roses. Here again, however, we can trace a regular gradation from the small white blossoms of the may, through the larger blushing pink flowers of the apple, to the very expanded and brilliant crimson petals of that beautiful ornamental species of pear, the Pyrus japonica, so often trained on the sunny walls of cottages.

The quince is another form of apple very little removed from its congeners except in the fruit. More different in external appearance is the mountain-ash or rowan-tree, which few people would take at first sight for a rose at all. Nevertheless, its flowers exactly resemble apple-blossom, and its pretty red berries are only small crabs, dwarfed, no doubt, by its love for mountain heights and bleak windy situations, and clustered closely together into large drooping bundles. For the same reason, perhaps, its leaves have been split up into numerous small leaflets, which causes it to have been popularly regarded as a sort of ash. In the extreme north, the rowan shrinks to the condition of a stunted shrub; but in deep rich soils and warmer situations it rises into a pretty and graceful tree. The berries are eagerly eaten by birds, for whose attraction most probably they have developed their beautiful scarlet colour.

So far, all the members of the rose family with which we have dealt have exhibited a progressive advance upon the common simple type, whose embodiment we found in the little wayside potentillas. Their flowers, their fruits, their stems, their branches, have all shown a regular and steady improvement, a constant increase in adaptation to the visits of insects or birds, and to the necessities for defence and protection. I should be giving a false conception of evolution in the roses, however, if I did not briefly illustrate the opposite fact of retrogressive development or degeneration which is found in some members of the class; and though these members are therefore almost necessarily less familiar to us, because their flowers and fruits are inconspicuous, while their stems are for the most part mere trailing creepers, I must find room to say a few words about two or three of the most noteworthy cases, in order to complete our hasty review of the commonest rosaceous tribes. For, as we all know, development is not always all upward. Among plants and animals there are usually some which fall behind in the race, and which manage nevertheless to eke out a livelihood for themselves in some less honourable and distinguished position than their ancestors. About these black sheep of the rose family I must finally say a few words.

In order to get at them, we must go back once more to that simple central group of roses which includes the potentillas and the strawberry. These plants, as we saw, are mostly small trailers or creepers among grass or on banks; and they have little yellow or white blossoms, fertilised by the aid of insects. In most cases their flowers, though small, are distinct enough to attract attention in solitary arrangement. There are some species of this group, however, in which the flowers have become very much dwarfed, so that by themselves they would be quite too tiny to allure the eyes of bees or butterflies. This is the case among the meadow-sweets, to which branch also the spiræas of our gardens and conservatories belong. Our common English meadow-sweet has close trusses of numerous small whitish or cream-coloured flowers, thickly clustered together in dense bunches at the end of the stems; and in this way, as well as by their powerful perfume, the tiny blossoms, too minute to attract attention separately, are able to secure the desired attentions of any passing insect. In their case, as elsewhere, union is strength. The foreign spiræas cultivated in our hothouses have even smaller separate flowers, but gathered into pretty, spiky antler-like branches, which contrast admirably with the dark green of the foliage, and so attain the requisite degree of conspicuousness. This habit of clustering the blossoms which are individually dwarfed and stunted may be looked upon as the first stage of degradation in the roses. The seeds of the meadow-sweet are very minute, dry, and inedible. They show no special adaptation to any particular mode of advanced dispersion, but trust merely to chance as they drop from the dry capsule upon the ground beneath.

Fig. 48. — Single flower of Salad Burnet, male and female.

A far deeper stage of degradation is exhibited by the little salad-burnet of our meadows, which has lost the bright petals of its flowers altogether, and has taken to the wasteful and degenerate habit of fertilisation by means of the wind. We can understand the salad-burnet better if we look first at common agrimony, another little field weed about a foot high, with which most country people are familiar; for, though agrimony is not itself an example of degradation, its arrangement leads us on gradually to the lower types. It has a number of small yellow flowers like those of the cinquefoil; only, instead of standing singly on separate flower stalks, they are all arranged together on a common terminal spike, in the same way as in a hyacinth or a gladiolus. Now, agrimony is fertilised by insects, and therefore, like most other small field roses, it has conspicuous yellow petals to attract its winged allies. But the salad-burnet, starting from a somewhat similar form, has undergone a good deal of degradation in adapting itself to wind-fertilisation. It has a long spike of flowers, like the agrimony; but these flowers are very small, and are closely crowded together into a sort of little mop-head at the end of the stem. They have lost their petals, because these were no longer needed to allure bees or butterflies, and they retain only the green calyx or flower-cup, so that the whole spike looks merely a bit of greenish vegetation, and would never be taken for a blossoming head by any save a botanical eye. The stamens hang out on long thread-like stems from the cup, so that the wind may catch the pollen and waft it to a neighbouring head; while the pistils which it is to fertilise have their sensitive surface divided into numerous little plumes or brushes, so as readily to catch any stray pollen grain which may happen to pass their way. Moreover, in each head, all the upper flowers have pistils and embryo seed vessels only, without any stamens; while all the lower flowers have stamens and pollen bags only, without any pistils. This sort of division of labour, together with the same arrangement of seed-bearing blossoms above and pollen-bearing blossoms below, is very common among wind-fertilised plants, and for a very good reason. If the stamens and pistils were inclosed in a single flower they would fertilise themselves, and so lose all the benefit which plants derive from a cross, with its consequent infusion of fresh blood. If, again, the stamens were above and the pistils below, the pollen from the stamens would fall upon and impregnate the pistils, thus fertilising each blossom from others on the same plant — a plan which is hardly better than that of self-fertilisation. But when the stamens are below and the pistils above, then each flower must necessarily be fertilised by pollen from another plant, which ensures in the highest degree the benefits to be derived from a cross.

Thus we see that the salad-burnet has adapted itself perfectly to its new mode of life. Yet that adaptation is itself of the nature of a degradation, because it is a lapse from a higher to a lower grade of organisation — it is like a civilised man taking to a Robinson Crusoe existence, and dressing in fresh skins. Indeed, so largely has the salad-burnet lost the distinctive features of its relatives, the true roses, that no one but a skilled botanist would ever have guessed it to be a rose at all. In outer appearance it is much more like the little flat grassy plantains which grow as weeds by every roadside; and it is only a minute consideration of its structure and analogies which can lead us to recognise it as really and essentially a very degenerate and inconspicuous rose. Yet its ancestors must once have been true roses, for all that, with coloured petals and all the rosaceous characteristics, since it still retains many traces of its old habits even in its modern degraded form.

Fig. 49. — Flower of Stanch-Wound or Great Burnet.

We have in England another common weed, very like the salad-burnet, and popularly known as stanch-wound, or great-burnet, whose history is quite as interesting as that of its neighbour. The stanch-wound is really a salad-burnet which has again lost its habit of depending upon the wind for fertilisation, and has reverted to the earlier insect-attracting tactics of the race. As it had already lost its petals, however, it could not easily replace them, so it has coloured its calyx or flower-cup instead, which answers exactly the same purpose. In other words, having no petals, it has been obliged to pour the purple pigment with which it allures its butterfly friends into the part answering to the green covering of the salad-burnet. It has a head of small coloured blossoms, extremely like those of the sister species in many respects, only purple instead of green. Moreover, to suit its new habits, it has its cup much more tubular than that of the salad-burnet; its stamens do not hang out to the wind, but are inclosed within the tube; and the pistil has its sensitive surface shortened into a little sticky knob instead of being split up into a number of long fringes or plumes. All these peculiarities of course depend upon its return from the new and bad habit of wind-fertilisation to the older and more economical plan of getting the pollen carried from head to head by bees or butterflies. The two flowers grow also exactly where we should expect them to do. The salad-burnet loves dry and wind-swept pastures or rocky hill-sides, where it has free elbow-room to shed its pollen to the breeze; the stanch-wound takes rather to moist and rich meadows, where many insects are always to be found flitting about from blossom to blossom of the honey-bearing daisies or the sweet-scented clover.

Perhaps it may be asked, How do I know that the salad-burnet is not descended from the stanch-wound, rather than the stanch-wound from the salad-burnet? At first sight this might seem the simpler explanation of the facts, but I merely mention it to show briefly what are the sort of grounds on which such questions must be decided. The stanch-wound is certainly a later development than the salad-burnet; and for this reason — it has only four stamens, while the parent plant has several, like all the other roses. Now, it would be almost impossible for the flower first to lose the numerous stamens of the ordinary rose type, and then to regain them anew as occasion demanded. It is easy enough to lose any part or organ, but it is a very different thing to develop it over again. Thus the great-burnet, having once lost its petals, has never recovered them, but has been obliged to colour its calyx instead. It is much more natural, therefore, to suppose that the stanch-wound, with its few stamens and its clumsy device of a coloured calyx instead of petals, is descended from the salad-burnet, than that the pedigree should run the other way; and there are many minor considerations which tend in the same direction. Most correctly of all, we ought perhaps to say that the one form is probably a descendant of ancestors more or less like the other, but that it has lost its ancestors’ acquired habits of wind-fertilisation, and reverted to the older methods of the whole tribe. Still, it has not been able to replace the lost petals.

I ought likewise to add that there are yet other roses even more degenerate than the burnets, such as the little creeping parsley-piert, a mere low moss-like plant, clinging in the crannies of limestone rocks or growing on the top of earthy walls, with tiny green petalless flowers, so small that they can hardly be distinguished with the naked eye. These, however, I cannot now find space to describe at length; and, indeed, they are of little interest to anybody save the professional botanist. But I must just take room to mention that if I had employed exotic examples as well as the familiar English ones, I might have traced the lines of descent in some cases far more fully. It is perhaps better, however, to confine our attention to fairly well-known plants, whose peculiarities we can all carry easily in our mind’s eye, rather than to overload the question with technical details about unknown or unfamiliar species, whose names convey no notion at all to an English reader. When we consider, too, that the roses form only one family out of the ninety families of flowering plants to be found in England alone, it will be clear that such a genealogy as that which I have here endeavoured roughly to sketch out is but one among many interesting plant pedigrees which might be easily constructed on evolutionary principles. Indeed, the roses are a comparatively small group by the side of many others, such as the pea-flowers, the carrot tribe, and the dead-nettles. Thus, we have in England only forty-five species of roses, as against over two hundred species of the daisy family. Nevertheless, I have chosen the rose tribe as the best example of a genealogical study of plants, because most probably a larger number of roses are known to unbotanical readers than is the case with any other similar division of the vegetable world.