Terry Kinney, Forest Whitaker, and the soldiers in Body Snatchers.

To represent is already a murder.

—Georges Bataille (1952)

Abel Ferrara is to cinema what Joe Strummer is to music: a poet who justifies the existence of popular forms. Without them, the genre film or the pop song would be no more than objects of cultural consumption. In this material world run on injustice and terror, where “popular” is confused with “industrial,” any cultural expression that does not hurl an angry cry or wail a song of mad love (often one and the same) merely collaborates in the regulation and preservation of this world. Is Ferrara, along with Jim Jarmusch, Tsui Hark, and Kinji Fukasaku, right to (even accidentally) redeem genre cinema? Would it not be preferable for them to desert the dirty terrain of what Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer named the “culture industry” and, like Jonas Mekas or Stan Brakhage, invent their own territories, forms, and artistic gestures?

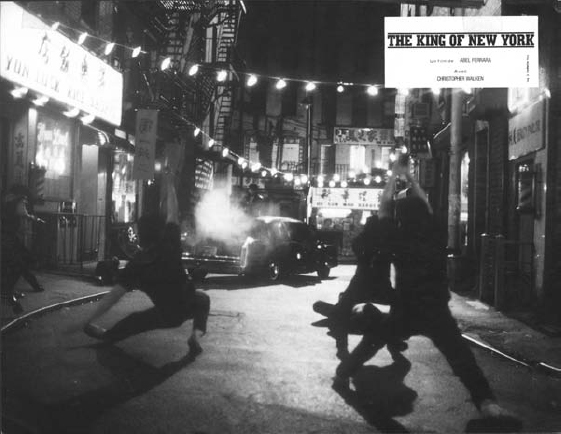

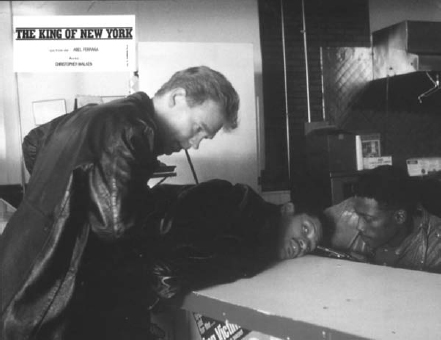

Ferrara’s films offer an answer. How could anyone except a melancholic criminal speak to us in the name of the good (King of New York; 1990)? Who but a paranoid cop could make us believe for a second in the virtues of forgiveness (Bad Lieutenant; 1992)? Who today could bear to listen to a moral lesson if it was not acted out by a drug-addicted, leprous vampire (The Addiction; 1995)? Who could interest us, even for a moment, in the tired old questions of the family unit or the individual? Who could continue to arouse in us a desperate faith in sacrifice and love, unless they were almost autistic, completely crazed, haunted figures within films that cultivate advanced arguments concerning the need to destroy all filmic forms?

Ferrara was born on 19 July 1951 to an Italian American father (who turned from being a bookmaker to a stockbroker) and an Irish American mother. He is the youngest of six children, with five sisters. The Esposito family (renamed Ferrara by Abel’s grandfather after he emigrated to the United States) originates in Salerno, south of Naples. Ferrara studied at the Sacred Heart Catholic School in the Bronx: “You were in, like, the front row and there was this giant crucifix, about eight feet tall, dripping blood.”1 In 1966, the family moved to the Peekskill district. At Lakeland High School, Ferrara met Nicodemo Oliverio (a.k.a. Nicholas St. John) and John Paul McIntyre. He and St. John formed a rock band, bought an eight-millimeter camera, and made their first ten-minute short, “The story of a kid who liked getting drunk with his friends.”2 Ferrara returned to New York to study cinema at the State University of New York at Purchase and made a series of very short films (one or two minutes each) on Super 8 and sixteen-millimeter, devised as protests against the Vietnam War. As part of his studies he spent a year in Britain, where he participated in his first professional thirty-five-millimeter shoot for the BBC. Then he returned to New York and reunited with St. John; together they started writing and making films and playing music.

Ferrara’s œuvre can be read as a critical revitalization of the codes of genre cinema. He has tackled almost every popular genre: pornography (9 Lives of a Wet Pussy; 1976), gore (The Driller Killer; 1979), the rape-revenge movie (Ms .45, a.k.a. Angel of Vengeance; 1981), the thriller and film noir (Fear City, 1984; China Girl, 1987; King of New York, and Bad Lieutenant), the television cop series (two episodes of Miami Vice, 1985; The Gladiator, 1986; and Crime Story, 1986), science fiction (Body Snatchers, 1993; New Rose Hotel, 1998), fantasy-horror (The Addiction; 1995), the film-within-a-film (Dangerous Game, a.k.a. Snake Eyes, 1993; The Blackout, 1997), and historical re-creation (The Funeral, 1996; ’R Xmas, 2001.) Even music video has not escaped Ferrara’s enterprise (“California”; 1996). Ferrara has now announced, among several projects that may be shot in Italy, that he will direct a comedy titled Go-Go Tales.

This critical interrogation of generic codes resembles neither a stylish reworking nor a simple exposure of cinematic clichés. It is a matter of formulating, thanks to an arsenal of basic, immediately comprehensible archetypes, certain primal, practical, and troubling questions. What are the limits of identity? What is an individual? What is a social subject? What are we conscious of? What are we responsible for? Adrian Martin has put it well: “Every problem in Ferrara’s films is a social problem, a problem endemic to the formation and maintenance of a human community.”3

It is telling that Ferrara made his most violently inventive film-tract when he was unwisely let loose at the heart of the Hollywood system. Body Snatchers, in this regard, forms a crucial diptych with Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers (1997). Ferrara’s work introduces disorder into a cynical world; misunderstandings begin here, since some critics attribute this disorder to the films themselves. His films are increasingly accused of being badly made, murkily motivated, and confused—especially The Blackout and New Rose Hotel.

Crucially, there is no “angelism” in relation to evil and negation in Ferrara, no implicit belief in an ideal perfection or state of innocence. If scarcely a trace of utopia or any radical counterproposition can be detected, this is at least as much due to a fidelity to the negative as to the fact that everything in this world is already in a state of ecstasy, exaltation, and pure inebriation. As Ferrara said of Thana (Zoë Lund, née Tamerlis), the heroine of Ms .45: “Beyond the reasons that this girl has to kill—revenge, justice, all that—there is also pleasure of a sexual kind in violence.”4 So which is more cruel, the cynical world, or the man who merrily draws from it for his films, without pretending to change anything?

The aesthetic limitations of Ferrara’s work are obvious. His cinema needs characters, narrative, mise en scène, and genre. More precisely and intensely, he needs the irreducible element at the heart of each of these modes: archetype, fable, staging, and standard imagery, respectively. As for Ferrara’s public image, it is fascinating to the extent that it offers a smokescreen for the work itself. In the 2003 catalog for the cinephilic Locarno Film Festival, Ferrara is presented as “deranged.” For the press, he will always be that big kid (now more than fifty years old) who strums his guitar instead of answering questions, lives in a perpetually dishevelled state, and leads journalists to the heights of poetically burlesque absurdity.5

In the range of figures allowed by the culture industry, Ferrara occupies the place of the “maverick”—half-Dionysus by virtue of his cultlike devotion to alcohol, half-Orpheus by virtue of the lyre that never leaves his side. Just as Madonna, Lili Taylor, and Béatrice Dalle have come to replace Marilyn Monroe, Frances Farmer, and Mae West in their public personae, Ferrara is reassuringly inscribed in the line of those grand eccentrics who maintain the fragile continuity between the industry and the avant-garde: Josef von Sternberg, Erich von Stroheim, King Vidor, Orson Welles (a photo of whom decorates Ferrara’s bedroom), and Nicholas Ray.

Ferrara calls himself the “master of provocation.”6 His œuvre affirms the value of explosive outbursts. In the script for Mary (first written in 2000 and subsequently reworked)—the central subject of which is the shooting of a film about Jesus—the director, James, threatens the projectionist, forcing him to continue a screening; he ends up watching the film alone, gun in hand.7 For Ferrara, images are a matter of life and death. Whether one creates or simply looks at a film, it must constitute an event in the existential sense of the word. He once stated, “You should be willing to die for a film.”8 But why accord such importance to images, to the realm of the symbolic? And how to deal with the requirements of such an exacting and lofty position?

This book is the fruit of an annual seminar devoted to Ferrara’s work that I have been teaching at Université Paris I since 1996. I have been able to measure, over this time, the constant enthusiasm elicited in students and guests (some of them filmmakers) by Ferrara’s films. Each two-monthly encounter is dedicated to a different dimension of the Ferraran corpus—for example, “The Dreamer Killer” in 1998–99, “Evil without Flowers: Ferrara and the History of Theories of Evil from the Ancient Greeks to Hannah Arendt” in 1999–2000, or “Right, Liberty, and Criminal Life” in 2003–4. This book does not terminate the analysis. We can see here one sign among many of the interest in and admiration for Ferrara shown over many years by French and other European cinephiles. His first major interview appeared, under the title “American Boy,” in a 1988 issue of La Revue du cinéma, thanks to Alain Garel and François Guérif.9 The Cinémathèque Française, under Jean-François Rauger’s initiative, organized a comprehensive retrospective of Ferrara’s career in 2003. In Italy, the first monographs on the director were produced in 1997, followed by several book-length studies.10 The Venice Film Festival has often honored Ferrara’s films: Chris Penn received an acting award for The Funeral, while New Rose Hotel received the International Critics’ Award. Critical recognition of the same order has occurred in Ireland, Austria, and Germany. In Britain, Brad Stevens dedicated five years to writing and researching a magisterial reference book, Abel Ferrara: The Moral Vision.

Appreciative American commentaries are not entirely absent, starting with the essays and in-depth interviews by Gavin Smith and Kent Jones.11 Yet it seems that Ferrara’s work has encountered enormous resistance in the United States, where his four most recent films (The Blackout, New Rose Hotel, ’R Xmas, and Mary [2005]) have hardly been screened in cinemas. Asked what he would do if ’R Xmas failed to achieve American distribution, Ferrara responded with his customary drollness: “‘We burn the negative. We eat the negative with tomato sauce. On D. W. Griffith’s grave.’”12 Moreover, when a Ferrara film is produced and distributed by the American industry, it does not necessarily fare any better. As Jonathan Rosenbaum commented in 1994, “[C]ertain studios perversely want certain good films to fail, e.g., most recently and blatantly, Paramount and Peter Bogdanovich’s The Thing Called Love, and Warner Brothers and Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers.”13 I want to show why the culture industry has good reason to repress Ferrara, just as it repressed Orson Welles, Monte Hellman, and Charles Chaplin.

There are three essential propositions underlying Ferrara’s work:

1. Modern cinema exists to come to grips with contemporary evil. On this level, Ferrara’s enterprise renews for the twenty-first century what Roberto Rossellini accomplished for the twentieth. To respond to this challenge, Ferrara’s work produces forms of synthesis at the levels of the individual films and the sum of his work as a whole. From a thematic viewpoint, his work explores the articulation of two of the century’s emblematic criminal logics, the Mafia and capitalism.

2. In contrast to other filmmakers who are drawn to the same conception of history—that the only story is the story of evil—Ferrara follows an optimistic conception, thus preserving a sense of tragedy. This gives rise to the elaboration of characters who are in revolt, whether political (revolutionaries) or psychic (the great tormented). Such characters pose anew the question of the individual, but they all derive from the prototype of the visionary.

3. The treatment of historic evil requires the invention of filmic forms that express what is inadmissible in terms of behavior, morality, narrative, image, sound, and especially in terms of architechtonic and compositional invention. Provocative storylines (concerning murder, injury, apparent amorality, rape, and violence of every kind) are merely the currency of a structure of inadmissibility, the reign of injustice. Ferrara’s work seeks to elucidate the basic elements of this structure in terms of an economy that is at once psychic and political.

Figurative Synthesis Two films manifest Ferrara’s genius for figurative synthesis in a particularly clear way: Body Snatchers and The Addiction. (Plot synopses for all films analyzed can be found in the filmography.)

The “snatching” principle lends itself to an infinite play of metaphors. Discussing Jack Finney’s 1955 novel The Body Snatchers, which has so far inspired three films (with a fourth reportedly on the way), Ferrara declared: “The book—it’s beautiful. It’s a metaphor like an image in a million mirrors—y’know what I mean? It’s infinite.”14 His version of the Body Snatchers story covers at least three dimensions of human experience: it is a “family romance” (a teenaged girl symbolically kills off her family); a futuristic essay on industrial pollution and global militarization; and a retrospective meditation on “Hiroshima man,” in which all is shadow, a “haunted outline,” where every silhouette can only be envisaged from the viewpoint of its imminent disappearance. This is figurative work on the most violent act of aggression ever inflicted upon humanity. Body Snatchers asks the historical question, What can the destruction of Hiroshima or Nagasaki tell us about the liberal, democratic society responsible for it? Its collective political question is, What can the individual do when faced with the deathly logics at work in the industrial standardization of the entire world? And its intimate, biological question is, What is revealed to us by this dream of a teenaged girl, Marti (Gabrielle Anwar)—a lethal fable invented so that she can do away with her brother, mother, and father—about the life-drive, the reproductive function of which she supposedly embodies?

How does the film interrelate these three dimensions? This can be determined clearly in the sequence depicting the Malone family arriving and setting itself up at the military base. The father, Steve (Terry Kinney), is about to lead a scientific inquiry into the toxicity of certain chemical weapons. Two worlds are depicted in parallel montage: the private world of the family with its warm, childlike atmosphere, and the dark, menacing world of the military camp. The latter is presented via a successive piling-up of collective evils: general world pollution; an explicit reference to the history of armed conflict, namely the first Gulf War (General Platt [R. Lee Ermey] reproaches Steve, “You know absolutely nothing about biological and chemical warfare”); an allusion to Nazism, via the nocturnal spiriting away of an anonymous victim by a fearsome commando unit; a triple superimposition of military, industrial, and criminal orders; and a reference to Hiroshima in the striking, spatially mismatched shot of three soldiers’ shadows in the dust behind the kneeling Steve. These shadows inscribed in the toxic dirt—recalling the outlines of bodies imprinted onto Hiroshima’s walls—anchor the figurative treatment of the snatchers as sketches, obscure silhouettes and undecidable effigies within a specific historical abomination.

The question of the scene thus becomes, What is the relation between the two universes, intimate (the family) and collective (war)? Major Collins (Forest Whitaker) forges this link when he asks Steve, in the middle of the latter’s examination for toxic chemicals, “Can they affect the brain patterns? Can they interfere with chemo-neurological processes? … Simply, can they alter a person’s view of reality?” This is the practical question explored by every Ferrara film: How does evil attach itself to bodies and the psyche? In Body Snatchers, this question immediately receives a doubly affirmative response: evil attaches itself to bodies by spatial invasion, when a troop of soldiers instantly arrives to deposit suspicious boxes in the Malone home (the paternal bedroom thus becomes a toxic depot), and by mental invasion, when all the children in day care except Andy (Reilly Murphy) hold up their identical drawings of bloody viscera, evidence of the barbaric confiscation of their imaginaries.

From this example, the method of Ferrara’s style can be deduced. It proceeds by a figurative and kinetic synthesis. The film ceaselessly establishes links between phenomena by way of circuits of propagation, contamination, and invasion. Body Snatchers begins this process by describing the destruction of intimacy by collective evil in order to deepen our understanding of the way in which intimacy is itself invaded by the germs of hatred and cruelty. As we will see, this is what is at stake in the film’s depiction of the maternal.

The Addiction explores a historical synthesis. It offers, for cinema, a balance sheet of the twentieth century. The principle of vampirism—a particularly rich figurative schema—signifies the Vietnam War, Nazism, drugs, all contagious diseases such as AIDS, American imperialism, and poverty. Ferrara’s work, in coming to grips with modern evil, can be envisaged as an ever more carefully argued-out description of capitalism as catastrophe. This polemical enterprise begins with The Hold Up (1972), a fifteen-minute short written by St. John (credited under his real name, Oliverio). In synopsis, the film’s politics are crude: a group of workers, victims of economic retrenchment, hold up a service station. They are arrested. The boss’s son-in-law is freed, while his two accomplices, ordinary workers, end up sentenced and imprisoned. Criminalized capitalism, complicit unions (the sackings are announced by the union delegate), generalized corruption, and institutionalized injustice: The Hold Up paints the backdrop upon which Ferrara’s features (King of New York, Body Snatchers, New Rose Hotel) will develop much fuller and more violent elaborations. The final shots of The Hold Up radically depict the factory as a prison—like a visual reprise of the celebrated sequence in Rossellini’s Europa ’51 (1952) where Ingrid Bergman, returning from her first day of factory work, declares to Giulietta Masina, “I thought I was seeing convicts.” The assimilation of factory to penitentiary inaugurates Ferrara’s succession of metaphors for economic alienation. The capitalist system is figured as a toxic military base in Body Snatchers; the underground drug economy greases the wheels of the above-ground economy in King of New York; and industrial, scientific, and state-run networks nestle within criminal organizations in New Rose Hotel.

Terry Kinney, Forest Whitaker, and the soldiers in Body Snatchers.

Terry Kinney and the shadows of three soldiers in Body Snatchers.

So what becomes of the human? In The Driller Killer and later The Addiction—twin films in many respects—capitalism is shown from the viewpoint of its victims: the depressing poverty of urban dereliction, bums, junkies, and all the little people who are economic castoffs, slowly dying in the street, at anyone’s mercy. In Body Snatchers, over the course of the fifty most terrifying, synthetic seconds in narrative cinema, the human is transformed into rubbish. In a slow-motion sequence-shot, the false, snatched mother, Carol (Meg Tilly), moves toward a truck, carrying a garbage bag that contains the remains of the real mother. Much is fused in this image of man-as-ashes: the Nazi ovens, the obliteration of bodies in Hiroshima, and the contemporary transformation of genetic patrimony into industrial property—three of the principle modern attempts at annulling humanity, whether by pure and simple disappearance (Nazi camps, Hiroshima) or by industrial reduction to the state of raw material (genetic industrialization). The dark, speckled brilliance of the asphalt upon which the menacing mother advances with her bag of remains evokes an archaic, mythological kind of figuration: the inaugural turbulence of atoms, as per Heraclitus and Lucretius. It is as if Ferrara aims to show the origin of life along with its symbolic disappearance. The narrative premise of Body Snatchers evokes a fatality without remission, clinched by the fact that it is the mother who performs this gesture of getting rid of humanity. She who gives life fulsomely propagates death, not only physically but also symbolically; the quotidian banality of her gesture renders it all the more ineluctable. But the lap-dissolve that begins the sequence-shot, superimposing the disturbed face of Andy upon the cosmic asphalt, suggests that it is all the nightmare of a young boy. In New Rose Hotel, however, there is no longer either dereliction or bodily waste—the human factor is contained on a computer disc, no longer anchored in warm, living bodies. It has been entirely coded and can thus be entirely erased.

A Polemical Enterprise Ferrara has often expressed his admiration for the exacting artistry of John Cassavetes, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Several principles unite the respective works of these four filmmakers. First, a practical principle: the constitution of a variable but faithful group of collaborators (Ferrara’s team includes the writer Nicholas St. John, the composer Joe Delia, the cinematographer Ken Kelsch, the editor Anthony Redman, the producer Mary Kane, and the writer/actor Zoë Lund). Second, a stylistic principle: the exclusive privilege accorded by these filmmakers to the description of human behavior via gestural, actoral, and emotional invention. And a third, a fundamental theoretical principle: these filmmakers explicitly conceive of their work as a vast enterprise of political critique. This conception is most evident in the cases of Pasolini and Fassbinder.

For Fassbinder, each film constitutes a polemical treatise on Germany, past and present. His work never ceases to investigate five points: 1) the remnants of Nazism in contemporary Germany; 2) the moral nullity of liberal democracy; 3) the historical hypothesis that capitalism can accommodate itself to any political regime whatsoever, whether democratic or fascist; and, as a corollary to that, 4) Nazism as the ideal regime for capitalism, since it reduces workers to a “workforce” that does not need to be supported, only exhausted to the point of death and then instantly replaced (I. G. Farben paid Auschwitz prisoners); and 5) the servile ideological role of the culture industry.

Pasolini’s work is organized on the basis of a central critical point: acculturation. This engenders a melancholic hypothesis concerning the disappearance of certain archaic forms of Italian civilization. While Fassbinder’s work (like Ferrara’s) declares itself to be entirely negative and purely polemical (in the great tradition of the Frankfurt School), Pasolini’s work presents at once a negative side (the angry description of the forms of human nature’s destruction) and an affirmative side (an affirmation of the survival or the force of the good and the beautiful, which is for him mythological barbarity, elaborated in Medea, 1970; The Gospel According to Matthew, 1964; and Love Meetings, 1965). Both filmmakers are bent on preserving particular forms of beauty: neoclassical beauty, like the angel in Pasolini’s Theorem (1968) or the gay boys in Fassbinder; and subproletarian beauty, like the ragazzi in Pasolini or the way Fassbinder films his own body (in Fox and His Friends [1974], for instance). This is a dimension completely missing from Ferrara’s work; the beautiful appears nowhere in his representations. The beautiful and the good are either resolutely absent (as in Body Snatchers), rendered as repulsive (the “healthy” character in The Blackout, Susan [Claudia Schiffer]), profaned (the nun [Frankie Thorn] in Bad Lieutenant), or treated as a catastrophic, unliveable eruption leading to death (the crisis of L. T. [Harvey Keitel] at the moment of his redemption) or to self-annihilation (the ambiguous resurrection of Kathy [Lili Taylor] at the end of The Addiction). In Ferrara, the journey of goodness is rendered as endless suffering. At the antipodes to the sporadic Hellenism that appears in Fassbinder or Pasolini, the only “beauties” in Ferrara are criminal, Baudelairean, infernal bodies.

Modern Forms of Allegory Ferrara, Cassavetes, Pasolini, and Fassbinder plumb, within the order of figuration, a common resource: the elaboration of modern cinematic allegory, in forms determined by these filmmakers’ polemical enterprises. Cinematic characters often represent exemplars or values such as law, revolt, or normality, but that is a matter of emblems or archetypes, not allegories. Allegories presuppose a strong conceptual construction. The conceptual elaboration of an allegory, sometimes complex and unfamiliar, opposes itself to the principle of recognition, the already seen and already known, which is the realm where archetypes work. It is in this sense, perhaps, that Walter Benjamin claims that “[a]llegory is the armature of modernity.”15

Consider, for example, the character of Willie (Hannah Schygulla) in Fassbinder’s Lili Marleen (1981). A singing star, Willie is a purely logical figure representing the point of confusion between antagonists: she maintains the link between Nazism and the Resistance (as a symbol of the Nazi regime, she has a lover inside the Resistance); between the German and Russian armies, which halt fire in their trenches to listen to her songs; and between the Jewish music that she replaces on the radio and the censorship that she herself suffers. In short, she is a modern allegory—not an entity that cloaks a concept in a body by means of a panoply of emblems (Justice with her scales and sword, Cupid with his garland and arrows) but a logical movement of passage between conflictual entities. Fassbinder’s intent is strongly critical, since Willie is ultimately a figure for the German people.

Ferrara’s allegorical invention is especially kinetic: his characters allegorize not fixed notions but questions or problems. Marti in Body Snatchers represents what is archaic in the human psyche; Kathy in The Addiction represents the (highly ambiguous) principle of historical guilt; Matty (Matthew Modine) in The Blackout represents the workings of an abandonment complex. Note, however, that Pasolini, Fassbinder, and Ferrara classically maintain character as the figurative site for allegory, whereas Jean-Luc Godard works by constellation and dispersion across several figures, as the filmmaker Gaspard Bazin (Jean-Pierre Léaud), relating the technique to its pictorial origins in Titian, outlines clearly in Grandeur and Decadence of a Small-Time Filmmaker (1986).

Dynamics of the System Pasolini, Fassbinder, and Ferrara proceed from the same cinematic origin: Rossellini. In all three cases, it is a matter of systematically coming to grips with contemporary evil. “Systematic” here means permanent, recurrent, and exclusive—for nothing is beyond the question of evil. But the formal translations of this systematicity for each filmmaker are rich and diverse. The elementary form of systematicity is the program, in the sense of a plan laid out in advance and progressively explored. This is the source of Rossellini’s inventiveness, not only in his great educational television works but also his postwar cycle of films. Rossellini set out to make a series of films on the disasters of war. Four installments were shot: Rome Open City (1945) and Paisà (1946) on the Italian resistance to fascism, Germany Year Zero (1947) on the physical and moral catastrophe provoked by Nazism, and Stromboli (1949) on displaced people. Another installment, a film on Hiroshima, was conceived; and Ferrara, in a sense, realized this project with Body Snatchers.

But Ferrara’s work invents other systematic forms at the heart of individual films as well as across all of his films: composition by anamorphosis (a key image is translated and metamorphosed in the course of a film, just as an anamorphic image can only be viewed correctly under certain conditions, such as through a lens or in a mirror that “unsqueezes” it); films conceived as counterparts of each other (Ms .45 is the female version of the male fable of The Driller Killer); scenes conceived as gestures of repentance for (or even a repainting of) other scenes (the rape in 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy is expiated in Ms .45); the progressive stretching from film to film of a figure that is initially simple in its symbolic operation, pushing it to its limits (the serial killer); the systematic declension of the same psychic motor—namely, passion—for all central figures; and narrative inversion, to posit a “reverse shot” to the entire system (in ’R Xmas, how to get free of evil when it is no longer experienced as criminal transgression but as an everyday norm). Generally, proof that a filmmaker’s œuvre is coherent is not especially remarkable or impressive. But in Ferrara’s case, this proliferation of systematic forms—on iconographic, narrative, stylistic, and logical levels, and from film to film—never ceases to amaze.

Preservation of Tragedy One concept unites Ferrara’s work with that of some of his contemporaries: the only story is the story of evil. Two possible positions instantly follow from this. The first is fatalistic (in the manner of Marguerite Duras’s famous phrase from The Truck [1977], “The world hurrying to its end, that’s the only politics”), demanding a frontal description of “the disaster,” whatever and wherever that disaster may be. The second position is tragic, maintaining a principle of resistance to evil while knowing all along that this resistance is doomed to failure. Ferrara is on the top rung of tragedians, even though, as a filmmaker, he is essentially boundlessly optimistic. Not because goodness (in the sense of an advent of social justice and thus of moral pacification) can ever become a reality, but because the annihilation of evil can be envisaged as the negation of negation. This is evident in the endings of Bad Lieutenant, The Addiction, and The Funeral.

In this respect, the frenetic treatment of goodness via the figure of the delirious ambulance driver (Nicolas Cage) in Bringing Out the Dead (1999) constitutes Martin Scorsese’s response to Ferrara’s use of Mean Streets (1973) in Bad Lieutenant and The Addiction. In all these films, fables of compassion and redemption have no efficacy unless they borrow the attributes (and the visionary stylistics) of crime stories: gestures of goodness are inverted into gestures of aggression; love of one’s neighbor becomes an almost cannibalistic desire; and empathy with the suffering of others leads to a criminal vertigo. In contemporary cinema, goodness, love, and compassion can no longer be represented with the kind of simplicity for which Rossellini provided the definitive model in Europa ’51. There must now be a true guardian of the law (not order but morality), whether psychopathic, incestuous, and mute (such as Takeshi Kitano in Violent Cop [1989]); drugged, libidinal, and mystical (Keitel in Bad Lieutenant); or hallucinating, irrational, and ineffectual (Cage in Bringing Out the Dead). Such a treatment of goodness, via the paradoxical adoption of traditional attributes of evil, culminates in the portrait in ’R Xmas of the cop (Ice-T) as a tempting, corrupt, anguished figure—in short, the serpent who must save Eve (the wife-mother, played by Drea de Matteo) from amorality lived as normality.

Fold and Pleat: Formal Logics of Metamorphosis To imagine the annihilation of evil there must be an exploration—not a simple antagonism of two opposed entities (good versus evil) but an intensification or deepening of a single entity. Ferrara’s films are structured like passages through the looking-glass; it is a matter of passing from the recto to the verso of a given situation or image. This gives rise to a typical narrative structure of Ferrara’s work. Films are organized upon a single major fold, where the beginning finally meets or “touches” the ending to offer a striking comparison, or a more gradual pleat, where the major fold is progressively translated throughout in a series of small folds (akin to a pleated skirt) over the entire structure of a film. Ms .45 is a representative example of a film with a major fold joining the start and end, while The Addiction and The Blackout offer models of the pleating structure.

Bad Lieutenant is exemplary in its demonstration of these dynamics. In terms of its major, overarching fold, it opens on a daily situation—a father taking his two sons to school in a pleasant suburb—in order to arrive, finally, at the catastrophic version of this same scene: L. T. driving the two young punks through a devastated New York. Whether folding or pleating, Ferrara’s narratives generally take an ordinary daily scene all the way through to its transformation into a disaster. They are organized according to two principal procedures: either they depict the integral time of a single folding trajectory (Ms .45, Bad Lieutenant), or they ceaselessly repeat and renew the inaugural fold in an echoing, insistent, and hence pleated way (The Driller Killer, The Addiction, The Blackout). Ferrara’s films are organized on the basis of a fully imaginary form: metamorphosis, a complete alteration or transformation in form, structure, or substance—a process that can seem magical or diabolical. Two major instances of metamorphosis offer possibilities for compositional invention: metamorphosis of the protagonist or of the film itself. The dynamic of Ferrara’s œuvre arises from the way it endlessly renews the relationship between these two instances.

Let us observe some examples of this dynamic. Ms .45 and Bad Lieutenant, the two films Ferrara made with Zoë Lund, operate upon a harmonious coincidence between the protagonist’s trajectory and the film’s own unfolding. Ms .45 recounts the progressive metamorphosis of a young woman, Thana, into an implacable avenger. The film takes us from an ordinary scene (a fashion preview in a garment factory) to its nightmarish revision (the fancy-dress office party that ends in bloodshed). Its ending thus elucidates its seemingly casual opening: the fashion preview poses human costume as an ordinary disguise for a social mise en scène of bodies entirely founded on relations of power and submission (the regal and contemptuous buyer, the cunning dresser, mistreated models, and passive workers). The final fancy-dress party, which puts the studio staff back into the scene, develops the film’s underlying postulate all the way to the end: relations between people, especially sexual relations, can only be criminal. The invited couples swap tidbits about vasectomies and how to buy virgins from Third World countries. The sexual horror institutionally acknowledged and left at the dialogue level as a factual referent is immediately translated into a fantastic plot event. The double rape of the virginal Thana is thus reinscribed in a general economy of body-exploitation perceived by the western imaginary as the natural order rather than an absolute injustice, signaled by the off-handedness with which the interlocutors discuss prices for young girls. Thana’s violence responds to this institutionalized horror: to kill everyone, from the factory boss (this derisory representative of the industrial order) and his colleagues to all the available men, women, and transvestites. No massacre will ever be proportionate with the real abomination. The figure of Thana brings to light the phenomenon of ordinary sexual violence—first as a private phobia, but ultimately as an ultrapowerful force in the daily world economy, the possibility of exploiting any body of any age in any way. As Lund stated in 1993, “Ms .45 is not about women’s liberation, any more than it is about mutes’ liberation, or garment workers’ liberation (the character was a presser), or your liberation, or my own. Notice that her climactic victim is not a rapist in the clinical sense. He is her boss. The real rapist. Our real rapist.”16

The anamorphic trajectory of Ms .45 is thus clear: the final catastrophic version (the bloody ball) brings to light the intolerable character of the socially domesticated violence lurking in the inaugural ordinary scene (the fashion preview). As at the end of The Deer Hunter (1978), where the protagonists’ journey into hell allows us to finally see the germinal violence surreptitiously at work in the gesture of a little boy playing sweetly in his room with a plastic revolver, here the rape-and-massacre fable develops the logic of aggression at work in the apparently anodyne gesture of a sleazy boss caressing his employee’s hair and takes it all the way.

Bad Lieutenant recounts the path of a tormented character towards conversion; like Ms .45, the film takes us from an ordinary scene to its devastated version. But this major folding trajectory enriches itself through a gradual, pleated structure of echoes and metamorphic waves. A fold at the film’s start takes us directly from the private (the family) to the public (the job), from L. T.’s two sons in the black car to two girls, shooting victims, in their white car, female corpses that L. T. regards (in a point-of-view shot) as sexual objects. The fold closes itself at the end of its trajectory on an exact reverse (the two young Latino rapists). But in between, it is also translated at least twice further: across the sexual couple (a woman and an androgyne) with whom L. T. dances, and the two young women in the stationary car whom L. T. orders to mime fellatio—as if to testify more clearly to the totally phantasmic nature of this echo. Ferrara’s scenes are less plot events than visual echoes. Their logic is not especially Aristotelian, for they are not determined by linkages of cause and effect or before and after. They belong to a psychic process: the reproduction of a trauma in multiple aftershocks.

Two figural energies are put to work here. The first is figurative elasticity, which concerns the amplitude of the vibration between the matrix and each of its singular echoes. For example, the erotic couple with which L. T. drinks and dances (a voluptuous naked woman and an androgyne) does not really resemble what it relays (the initial pair of boys) unless it is inscribed within the entire chain of visual transfers. The second figural energy is iconographic fertility, which concerns the possible diversity of the echoes (L. T.’s sons become women, androgynes, rapists). These two processes and their attendant energies—the extent of visual approximation that the matrix can bear (all the way to apparent dissimilitude) in figurative elasticity and the constant renewal of the motifs (all the way to their apparent dispersion) in iconographic fertility—attest to the gravity of the complex that the film addresses.

Liquidation of Western Philosophy The Addiction offers the clearest anamorphic structure of any Ferrara film to this point in his career; it features a double metamorphosis. On the level of its protagonist, the film offers the metamorphosis of a philosophy student into a vampire, and thus of a moral problem (collective historical guilt) into corporeal destruction (somatization). From the viewpoint of the film itself, the metamorphosis is the permanent conversion of historical information (images of the Vietnam War, Nazi death camps, and so on) into physical events (vampiric attacks). The film is an essay on the psychic effects of images that are so powerful that, once shown, they take over the fictional bodies: Kathy experiences, as if for the first time, the slides of the My Lai massacre, and her intellectual torment (who is to blame? how to make amends?) metamorphoses in the very next sequence into a fantastic vampirism. Encountering an image, and encountering a Vampire named Casanova (Annabella Sciorra): it is the same scene, first as documentary and then as allegory, and this conversion will reproduce itself with each new discovery of a documentary image. Vampirism offers a simple, universal, popular iconography for the treatment of a complex and universal political question: how to live with the knowledge of historic evil—the unending chain of genocides, public and private massacres, the reign of injustice, oppression, and corruption? How not to die from all this pain, anguish, and guilt? Kathy incarnates and overexposes the torment that western civilization strives daily to repress.

The film’s ending, with its sudden logical spin, responds to the simple conversion at its beginning (the slides incarnate themselves as vampires), offering a metamorphosis so rapidly dialectical that it defies our understanding. Kathy, drained of all blood, seems to pass away peacefully after having received her last rites. Her ghost returns to place a rose on her grave, which proves either that the peaceful laying-to-rest remains tentative, or that Kathy is the first in a line of angels who are a source of torment rather than protection. At the same time, on the strict evidence of what we see and hear, this problematic figure intellectually self-destructs, since she exits the film with these words spoken in voiceover: “Self-revelation is annihilation of self.” Nothing is liveable any longer: neither knowing the world (one can die from anguish), nor making amends (liquidation is never complete, torment always returns; the “unhappy consciousness,” as Hegel called it, has no historical use-value), nor self-awareness (which marks the fulfillment of a disaster, not its solution). Kathy’s character symbolically exhausts every option of western philosophy.

Beginning from Fantasy Other Ferrara films dissociate the protagonist’s trajectory from the work’s own unfolding. Dangerous Game, like the films based on total metamorphosis, proceeds through incessant variations upon the same scene (a husband-wife quarrel). But these characters do not undergo any metamorphosis; on the contrary, they are locked up in their closed identities, caught in the stickiness of the self—starting with the confusion of actor and individual. Here it is not differentiation but its absence—an indistinctness—that creates the conditions for a pathology. Body Snatchers has metamorphosis as its very subject: the fiction of extraterrestrial replacement works well as a treatment of anthropological mutation in the age of the genome, that is, the menace to the living posed by industrialization in an advanced capitalist regime that now readies itself to confiscate our human, genetic patrimony. This film plainly obeys the anamorphic logic of Ferrara’s work. At the start, in an eminently familiar domestic gesture, Marti, riding in the back of the family car, pushes away her stepbrother, Andy; at the end, she hurls him from a helicopter down into a world consumed by blood and fire. The fold is perfect. However, Marti’s problem is precisely that she refuses the proper metamorphosis to adolescence. One can read the Snatchers story as a psychoanalytic fantasy (or phantasm) arising from a general repulsion towards the body. To fantasize a body that is empty and never subject to chance, without difference from the Other, with no future: the Snatchers, far more effectively than any overt menace, are not only the catalyst that allows this family romance to develop (erasing a young girl’s father, mother, brother, and the whole world); they also offer a fantasy of the body delivered from its own weight, from conception, gestation, and child bearing. The Snatcher thus represents the Other as not the human but the female. To restore living reproduction to a vegetable (no longer animal) model allows the invention of a mode of gestation that no longer takes place within the body but anywhere in the exterior world (hence the imagery of pods in a swamp)—no longer an intimate, individual process but an anonymous, collective administration (the nocturnal military management of the pods); no longer an organic, affective fusion (the fœtus) but a reproduction that is always already separate from its source. That such a fantasy of engenderment of the living can be a part of a young girl’s dreams, paradoxically, is what singularly expands our grasp of what is human. Here we catch a glimpse of one of the anthropological horizons of Ferrara’s cinema: to reopen our conception of the human, starting from that aspect of humanity that is unresigned to the facts of being only itself—including the apparently most ineluctable and definitive biological determinations of human being.

Depicting the World A number of cases of figurative anamorphosis, structural or local, can be found in Ferrara’s cinema: for example, between the scenes of dancing and urban confrontation in China Girl, or between the release from prison at the start and the exit from the train station at the end of King of New York. This is not merely a matter of rhymes aiming to establish a thematic coherence but of constructing a film through the form of a passage between altered images. The stake of this recurrent construction (certain films, such as Cat Chaser [1989] and ’R Xmas, follow different logics) is not the closure or self-abolition of the film (as is the case in Violent Cop, where the reprise of the same shot of the cop crossing a bridge at the start and end signifies the desperate futility of the protagonist’s sacrifice) but an intensification by reprises and variations. Ferrara films plunge into the deep, unspoken, scandalous significations of a scene, a gesture, or an ordinary situation. Such a structure declares itself to be at once classical (in the sense of perfectly totalized) and eminently contemporary: it is the structure of the antiworld. One of the origins of this antiworld structure can be found in Lewis Carroll’s books, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass, and Sylvie and Bruno: we must pass through a double of our world to understand the original. In cinema, the two most popular models of such “shadow world” fables are Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), which dramatize, respectively, a crossing over into the doubled world and the construction of a double that is brought into our world.

Contrary to such traditional fictions of destiny or becoming, contemporary American cinema massively construes fable as nightmare, narrative as anamnesis (an obsessive remembering that is also an erasure of past trauma), and thus (retroactively) the world as Limbo. Brian De Palma’s Carlito’s Way (1993), Scorsese’s Casino (1995), Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995), and David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) all elaborate this kind of nightmare. Ferrara uses the same structure but transposes it into a realist context. In the process, he returns to an early, precocious occurrence of this form: Cassavetes’s The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1978). The opening and penultimate sequences of that film depict the same character, Cosmo (Ben Gazzara), abandoned by life on a sidewalk—in between, the fable unfolds within dreamlike Limbo-spaces (centered on the nightmarish insistence of Cosmo’s debt). Another concept—à la John Carpenter’s Village of the Damned (1995)—is to present the world as already its own double. Body Snatchers unites both major modes: anamorphic intensification of a family scene, plus the fantastic re-elaboration of the world as a terrestrial hell.

To put it another way, the great contemporary fabulations address the question of what can be depicted or represented. But they do this in a way completely opposite to the Freudian dreamwork, which dresses up a normal, standard situation in an oneiric image capable of opening an access-path to consciousness. Rather, it is a matter of exhuming the latent violence in a standard image (daily life), with the intention of reconstructing its most obscure and least acceptable determinations. Ferrara’s work on this level belongs to a collective American aesthetic movement. Its specificity at the heart of this current can be measured by the way it places a crucial structure—the narrative possibilities of what can be represented—at the service of a radical, critical project.

In coming to grips with the questions of evil and guilt, Rossellini found it necessary to renew fiction in order to restore our relation to belief and reason. Ferrara works on the same problem, but at the level of the body. His films invent powerful modes of somatization, or the translation of psychic, political, and economic phenomena into corporeal terms. This enterprise of translation never ceases reinventing the relation between mental image and concrete image, opening up an astonishing repertoire of altered bodies: suffering, wasted, angry, convulsive, collapsed, haunted, even absent. His characters throw the telephone out the window because the bill is too high (Reno, played by Ferrara himself, in The Driller Killer); shoot out the radio because it broadcasts bad news (L. T. in Bad Lieutenant); kill any man who insults a woman (Thana in Ms .45); compulsively machine-gun the facades of Chinatown real estate (Mercury [David Caruso] in China Girl); erase the world to transform it (Frank White [Christopher Walken] in King of New York); kill in order to grasp that the only story is the story of evil (Kathy in The Addiction). Ferrara’s protagonists—Reno, Thana, L. T., Frank, Kathy, the Tempio brothers (Walken, Christopher Penn, and Vincent Gallo) in The Funeral, Matty and Mickey (Dennis Hopper) in The Blackout—represent figures of possession. Burdened with an undiminished fury, these characters are filled with an overflowing pain and a sublime ethical project that leads them to death.

System of Ethical Life What logic underpins Ferrara’s system? First of all, two models should be set aside. This logic is not a doctrine that can be applied from one film to the next, over and above the content of the individual fictions. Even if the character of Johnny (Gallo) in The Funeral—violent, communist, hypersexed, and full of integrity—seems like the most seductive and idealized figure in his films so far, Ferrara nonetheless declares himself to be a perfect dandy who believes only in “antipolitics,” brandishing the motto, “I’m a limousine liberal.”17 Nor does the Ferraran system rest upon the principle of taxonomy or cartography—the exhaustive filling-in of an already mapped territory. Rather, his aesthetic system proceeds from a logic of extension and a politics of reprise. It is because of these reprises that we see—as one rarely does in cinema, beyond the major example of Godard—an artist reflecting on the sense of his own work.

A first form of reprise is reparation: posing a film as an act of repentance for (and also “repairing” of) previous images. Two instances of this process can be cited. The first is purely axiological: the relation between the two episodes of the television series Miami Vice that Ferrara directed in 1985. “The Home Invaders” (episode 20) represents the televisual norm in its brute state: a band of young Latin American thugs burgle a rich Miami family; our friendly detectives (led by Sonny Crockett [Don Johnson]) identify, apprehend, and punish the culprits. Beating up a guy who is poor, young, immigrant, and clandestine in the name of respect for private property is considered honest work, a mission, a necessity—helpful, and also good fun. In an agonized stab at redemption for this (in its own way) criminal subjugation to television’s rules, “The Dutch Oven” (episode 27) embodies the general transgression of such rules. This time, the fiction depicts the murder of a bad guy by a female cop, Gina (Saundra Santiago), and the guilt that this engenders. Ferrara employs a wayward approach to narrative that favors description over action and liberates the possibility of working with mental images—a prelude to the complex superimpositions in The Blackout. In the context of a popular television series, “The Dutch Oven” constitutes an astonishing disavowal of police activity, problematizing the law on political and affective levels.

The second instance of reparation evokes a figurative deontology (a science of duty or moral obligation, or a code of ethics). In one sequence in The Blackout, a video artist (Mickey) directs an extra (“Annie 2” [Sarah Lassez]) to seduce an actor (Matty) and obtain from him the image lacking from the film-in-progress titled Nana Miami: a murder. Immediately absorbed into this fiction, the extra is drawn into a criminal economy. She disappears twice over, assassinated as a character and repressed as a memory, confused with the model for whom she offers a shadow-double. New Rose Hotel begins from the same situation and extends it to the scale of an entire film, so as to finally arrive at its moral reversal. Two men (Fox [Christopher Walken] and X [Willem Dafoe]) direct a young woman (Sandii [Asia Argento])—utterly interchangeable with the other women on stage with whom we first glimpse her—to seduce a third man (the Japanese scientist Hiroshi [Yoshitaka Amano]). But this aspiring actress proves herself to be not only a simulator incarnate but also the supreme femme fatale—the mythic Pandora who annihilates her designated victim, her creators, and mankind in general.

However, what is morally unbearable in The Blackout—to summon up a body, render it secondary, and supplicate and sacrifice it, all in ten minutes of film—is ultimately pressed into the service of its crowning image. The superimposition of the murderer and his victim evokes an iconographical reference: the adoration of the Virgin, or hyperdulia.18 The film includes this representation on two conditions: First, that the Virgin disappears, physically erased by the man who adores and symbolically kills her, since she is already dead and thus insignificant in the shadow cast by the gigantic, absent body, “Annie 1” (Béatrice Dalle)—the Mother, wife, star, and (in terms of Lacanian psychoanalysis) “block of the Real.” Second, this Virgin must also be the Mother, but one whose son has been aborted. However, even this figural apogee will not suffice. New Rose Hotel reinvests this figurative guilt even more profoundly. Sandii, the woman who was initially only an extra, becomes a central character: the angel tattooed on her belly rises (in a lap dissolve) over the entire world, and the actress destroys everything in her path. The entire film is organized according to a logic of denial that transforms destructive power into passionate affirmation. In an era of integral industrialization of the living (from which the zaibatsu draws its resources), woman no longer constitutes the indispensable source of human life—she has become a mere accessory. Nevertheless, if we attribute a universal power to destruction (Pandora), woman remains an absolute origin. From The Blackout to New Rose Hotel, figurative repentance arranges itself around stakes of an anthropological order.

Critical Intensification: The Case of the Individual The exacerbated form of repentance leads us to the general dynamic of Ferrara’s system. It is characterized by a second form of reprise (also found in Orson Welles and Fritz Lang): critical intensification. Observe the evolution of a crucial Ferraran problem, the notion of the individual. Ferrara’s protagonists represent figures of the human insofar as the human is kept distinct from the individual, or insofar as intimate experience is kept distinct from individual experience. What is the individual today? (In tomorrow’s world, the question will be easy to answer: an individual is anyone you can clone.) The individual is a subject identical to itself, anchored in identity, resolving itself (at least practically) in its relation to the Other, whether under types of self-alteration (for instance, the experience of illness) or collective experience (the relation to diverse kinds of human groups, such as family, clan, or tribe). According to our modern western conception, the individual is assured of his or her singularity, irreplaceable, a subject of rights and morality. To this extent, the individual becomes a bad object for the moderns. “[T]he isolated being is the individual, and the individual is only an abstraction, existence as it is represented by the weak-minded conception of everyday liberalism.”19

The individual amounts, on the good side, to the sovereign subject and, on the bad side, to the autotelic subject (the subject as an “end in itself”). The entirety of modernity, from Nietzsche to the Frankfurt School, is in opposition to this concept of the autotelic subject who facilely becomes a simple object of identity. Ferrara’s cinema permanently shoves this crucial idea in our faces: the human is that which cannot find its limits. Nothing could be closer to Ferrara’s cinema, on this level, than the philosophical and literary work of Georges Bataille. Both share the postulate that an ethical life henceforth consists of finding forms of faith at the heart of human negativity—an enterprise that Bataille calls “hypermorality.” “[T]he Evil—an acute form of Evil—which [literature] expresses, has a sovereign value for us. But this concept does not exclude morality: on the contrary, it demands a ‘hypermorality.’”20

There are four kinds of hero in Ferrara’s films. First, we have those that take themselves outside individuation and identity (the wasted or the nameless, like L. T. in Bad Lieutenant and almost all the characters in ’R Xmas, or representative types, like the body snatchers). Second, there are those that directly problematize the question of identity, either through being actors (Sarah [Madonna] in Dangerous Game, Sandii in New Rose Hotel) or being mad (Chez [Chris Penn] in The Funeral); because they are addicts, as in all of his films; or because they are addicts, mad, and actors at once (Matty in The Blackout). Third, Ferrara’s heroes find themselves beyond individuation (the King of New York, the saintly figure that L. T. becomes in Bad Lieutenant, the formless larva into which Kathy is transformed in The Addiction). Peina (Christopher Walken), king of vampires in The Addiction, is presented as both super- and subhuman: superhuman because he is immortal; subhuman because he is burdened with the arrogance of keeping himself in shape, citing Baudelaire, and managing to drink tea, describing himself as “almost human.” And fourth, Ferrara’s heroes die in the process of upholding a tragic defense of the individual, as Major Collins in Body Snatchers kills himself to affirm the privilege of singularity over uniform collectivity. Contrary to the American ideology of narcissistic conquest, Collins’s suicide places the individual in a purely defensive position, with no choice other than self-erasure. When he disappears, so too does the humanist hypothesis of a worthy and righteous sovereign subject. Beyond him reigns the military, industrial, and psychic order—the American democratic capitalism responsible for Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A good synopsis of Body Snatchers can be found in Adorno’s Minima Moralia:

It is the signature of our age that no-one, without exception, can now determine his own life. … Even the profession of general no longer offers adequate protection. … It follows directly from this that anyone who attempts to come out alive—and survival itself has something nonsensical about it, like dreams in which having experienced the end of the world, one afterwards crawls from a basement—ought also to be prepared at each moment to end his life. … Freedom has contracted to pure negativity, and what in the days of art nouveau was known as a beautiful death has shrunk to the wish to curtail the infinite abasement of the living and the infinite torment of dying, in a world where they are far worse things to fear than death. The objective end of humanism is only another expression for the same thing. It signifies that the individual as individual, in representing the species of man, has lost the autonomy through which he might realize the species.21

“Realize the Species” Is the individual in Ferrara’s work thus reduced to a simple principle of resistance against all it encounters, or nothing more than the shocking scenography of its own liquidation? On the contrary, Ferrara’s cinema is tragic because it insistently fixes upon the “realization of the species”—something that real history (which Ferrara’s cinema tries to describe in the most rational way possible) is intent on whisking away. After the statement made by Body Snatchers—that the whole world and all minds are being poisoned by capitalist industrialization—after the disappearance of the human, and since “nothing is possible any longer” (the final line of Pasolini’s Medea), then what is there to say or do? For starters, one can verify and deepen this description of the state of things in more specific ways.

The Funeral and The Blackout, despite their differences, represent two “family romances” that transpose the universal investigation undertaken by Body Snatchers into the context of domestic intimacy. The same conclusion is reached: the self must be erased to accomplish the “religion of humanity” that Emile Durkheim posed as the good version of individualism.22 In The Funeral, Chez, the sick brother, must destroy destruction, the logic of pride and vengeance set up by his family. In a perfectly rational act of amour fou, he must kill his eldest brother, Ray (Christopher Walken), “kill” Johnny’s corpse, and finally kill himself. Maybe then the wives and fiancées, capable of reflection and kindness, might be able to live. In The Blackout, a man (Matty) must die in order to fail before the woman who initially desired his presence. The allegory contained in the final image—the male ghost inclined towards the sweet, nude, female ghost arising in a superimposition out of the dark sea—constitutes the complete unfolding of the way in which one being can lack another. The final question of the victim-phantom to the executioner-phantom who has rejoined her in death—“Did you miss me?”—represents the sacred development of the ordinary, lighthearted dialogue of the wife-husband greeting at the film’s start (Her: “I missed you” / Him: “Yeah? I missed you too, baby” / Her: “Impossible …”). The slightest lack in the other’s desire is developed to the point of catastrophe, opening a fissure in the couple’s fusion and triggering a deluge of scenarios of death and abandonment into which the characters dive. Whether on the plane of morality (The Funeral) or emotion (The Blackout), Ferrara’s characters cannot live if not in a state of amour fou.

What kind of humanity is this? That of the “just man,” in the realization of whose name the singular individual can abolish himself. This is the ethical grandeur of Ferrara’s work, its fierce call to dignity. It wreaks violence upon the concrete individual in the name of an ideal of fusion and love, while fully knowing and describing the pathological, morbid nature of this ideal. This is the same logic expressed by Walter Benjamin when he refutes the sacred character of particular existence in the name of an ethical life: “The proposition that existence stands higher than a just existence is false and ignominious, if existence is to mean nothing other than mere life. … However sacred man is (or however sacred that life in him which is identically present in earthly life, death, and afterlife), there is no sacredness in his condition, in his bodily life vulnerable to injury by his fellow men.”23

At the start of The Blackout, a man and woman (Matty and Annie) embrace; their kiss, instead of manifesting joy and mutual understanding, masks their disquiet and distance. In the unfolding by successive anamorphoses of this affective gesture across the film, there is a long figurative movement of successive correction and the tragic advent of the just man, he who has recognized, traversed, and absorbed all that is negative, plunged to the point of drowning himself in an abyss of lack so that, beyond his disappearance, the glimmer of an instant of pure adoration might finally appear. Body Snatchers establishes an analytic synthesis of the human and social condition that is beyond any specific time or place. This account, however, was further verified and specified by Ferrara, by confronting it with historical reality. The Addiction and New Rose Hotel each take up, in their own way, the figurative schema of Body Snatchers—in a body-to-body encounter, the self is captured and stolen. Both use the same archetype: Pandora, incarnated by Peina in The Addiction and Sandii in New Rose Hotel. But The Addiction treats the historical dimension of the problem in a recapitulative way. Kathy absorbs the collective catastrophes of the twentieth century (Nazism, the Vietnam War, poverty, pandemic diseases, and so on). New Rose Hotel treats the matter in a prophetic way, asking, What is the destiny of the body in an industrial regime of genetic licensing? Both films develop the same idea of a general erasure of the human race, whether by physiological and genetic confiscation (New Rose Hotel) or by moral and metaphysical subtraction (The Addiction).

Matthew Modine in The Blackout.

Both films end on a moral lesson of sorts. In The Addiction, this lesson is that the speculative faculty must be cultivated as an ultimate weapon—“self-revelation is annihilation of self,” like a resistance fighter who hides on his person the cyanide capsule that will allow him to remain free in death. New Rose Hotel takes another path. By preserving—against all historical evidence—biological prerogatives within the female belly, the film introduces us to the critical virtues of denial.

The problem can also be posed the other way around, as in ’R Xmas. In this film that ends with “to be continued,” hypermorality is confused with ordinary morality. As in The Funeral, criminal life is the normal state of the family, but now this state is lived as a peaceful happiness, no longer as a paranoiac, twilight madness. The protagonists live inside the serenity of evil, and the trajectory of the story comprises their blind and difficult journey towards the recovery of their rights. The true transgression henceforth consists of acceding to justice—obviously not to false legality, the bad capitalist jurisdiction that all previous Ferrara films critique, but a state in which “right and grace are confused.”24 ’R Xmas establishes the most terrible of claims concerning evil: no one can get away from it anymore; the individual henceforth bathes in it like a blissful reign whose negative nature is no longer perceived. No one can even imagine, as far as the human horizon extends, what a new understanding of sovereignty, or a possible form of justice, could be. Another, completely different option would be to pose the problem of evil without passing through the negative, as Scorsese envisaged in Bringing Out the Dead, an amicable, brilliant response to Ferrara’s cinema. It reverses the frenetic, agonised treatment of madness, crime, and misery in Mean Streets, Taxi Driver (1976), and After Hours (1985)—not to mention Bad Lieutenant, King of New York, and The Addiction—into the realm of compassion, charity, and the problematic of healing.

Film after film—whatever the conditions of production—the systematicity of Ferrara’s work is elaborated with a calm certainty. How does this level of systematicity sometimes remain unperceived by critics as mastery? There are two possible reasons: Ferrara’s cinema actively explores the forms of lack in a radical way—especially in New Rose Hotel, his masterpiece on this topic. More generally, because of the insistent motifs that constantly return, the psychic confusion of the characters is attributed to the work itself—which, in fact, treats this subject magisterially. So let us pose again the question of the individual, this time from the vantage point of its interiority.

Rough Beast, Scrap Heap, Authentic Virtue Consider the sequence in Bad Lieutenant where, under the sound of “Let’s Get High” by the Lords of Acid, L. T. goes to explain to his bookie, Lite (Anthony Ruggiero), that he intends not to settle his debt, instructing him instead to re-bet it. This scene offers an accumulation of forms of negativity on at least three levels. On the level of the narrative situation, L. T. is plunged into a spiral: he gets himself into ever deeper debt, puts himself in lethal peril, and continues to deny the risk. At this level, the scene could be taken to depict a simple “descent into hell”: visual obscurity, a trajectory complicated by the need to visit a cavern (the bar) with a death’s head, red chromatism, a religious thematic, and a backdrop of gothic debauchery (a dancer in a cage). But this picturesque iconography of hell stylishly declares its ornamental nature. It decorates a plastic and mental negativity that is more dangerous, one related to the elementary alternation between the visible and the invisible.

L. T. is a character who refuses to recognize anything, neither death nor the real. His path to the bar—staggering, eyes closed, totally lost in himself under the influence of crack—represents his blindness in physical terms. The stroboscopic light, in force from the moment of his descent, constitutes the plastic manifestation of this evident blindness. At this second, plastic level of the scene, the strobe effect can be understood in several ways. It allows us to reconstruct the psychic state of L. T.—hallucinating, confused, and prey to sensation. It transforms obscurity into a mode of self-perception—the passages of darkness, like so many small, insistent blackouts, de-realize phenomena, making them tremble and shudder. It leaves no room for any mode of apprehension beyond the alternation of blindness and dazzle, nothingness and excess. Perhaps most importantly, the stroboscope guarantees the indifference of the visible and invisible. Light and dark are no longer opposed; they work in concert to aggress and confuse figures. Bad Lieutenant contains one of the first truly symbolic uses of the stroboscope in cinema, after the tremendous plastic constructions of Ronald Nameth’s films (Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, contemporary with its technical invention in 1967) and the psychedelic installations of USCO in New York during the 1960s and 1970s. These works constitute the euphoric model to which Ferrara’s scene offers a dysphoric avatar.

The third level of the scene creates a particularly acute form of negativity, thanks to its play on all-pervasive indistinctness. L. T. is not a character who alters or degrades himself, as does Kathy in The Addiction or Matty in The Blackout (characters who suit the “descent into hell” schema rather well). On the contrary, he is a compact, heavyset figure who is never really touched by anything. This is violently verified by the piling-on of factors that annul various sorts of differentiation at each of the three stages of the sequence (entry/bar/return). The first stage is spatial annulment: By mismatches of position from one shot to the next, L. T. and his mentor-dealer (Nicholas DeCegli) are alternately placed in the guide position as they make their way through the dancing crowd. The spatial orientation, in front or behind, hardly matters; nor does the before or after, who guides or who follows. It is no longer the case that light illuminates or that space situates. The second stage is metaphysical annulment: L. T.’s central declaration to Lite—“No one can kill me. I’m blessed”—testifies to his delirious presumption, an impunity that annuls all chance or becoming. The dialogue here refers back to Budd Boetticher’s The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960), in which another hero swears that nothing can kill him, that he is blessed—with his companion’s response providing the text for the mother’s evil litany in Body Snatchers (“You’re all alone. Who are you gonna turn to now? Where you gonna go? Who you gonna trust?” in the former, matching, “Where you gonna go? Where you gonna run? Where you gonna hide? Nowhere. Because there’s no one—like you—left” in the latter). L. T.’s vital formula amounts to a radical denial; he is the very character of denial, the existential repression of death. The third stage, temporal annulment: In the return corridor, it is always—against all plausibility—the same Lords of Acid fragment, the same blue shadow, the same staggered walk; time has evaporated. The only changes are subtractive: the crowd has disappeared, the strobe has stopped, Lite is gone, and all traces of teeming activity have vanished. It is as if L. T.’s entry (stage one) constitutes the objective version of the scene for which his return (stage three), after the existential declaration (stage two), offers the subjective version, thus rendering it even more dreamlike, hallucinatory, and solipsistic. To put it another way, this nightclub sequence establishes a vast formal machine of annulment, modeled on L. T.’s denial: nothing matters, no accident can happen, everything can remain indistinct. L. T. is a figure of dark unconsciousness, closed in on himself, almost autistic, and totally impervious to suffering (he sees corpses as sexual objects and exploits a murder scene as an opportunity to grab a bag of drugs). He is the very figure of blindness avowed, named, and intensified.

In the terms of my argument, such a character represents not a drug addict or a corrupt cop but rather the contemporary incarnation of what Hegel calls “authentic truth,” which “has only one figure: that of heroic immersion in ethical totality.”25 Hegel is opposed here to Kant’s famous precept, “Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”26 Does a law need to be discussed? No, according to Alexis Philonenko: “[I]f the duty exists, there is no need to reflect, it is immediate, beyond discussion” (63). Philonenko describes the concept of authentic virtue as an absolute moral obligation, opposed to the “compatibility of understanding” for which Hegel reproached Kant: “Only immediate engagement in the ethical substance, without discussion or reasoning, in which the individual raises himself to the totality by sacrificing the particularity which defines him, testifies to the authenticity of existence” (64).

L. T. incarnates a raw engagement with immediacy “without discussion or reasoning.” This is not only because of his action at the nadir of material life, immersed in the lower depths, in essential needs and a life of drives. It is also because he replaces understanding with crazy affirmation (“I’m blessed”), on the one hand, and a bet, on the other hand, which in his case does not proceed by deliberation and calculation but illumination (“I was at the game today, face to fucking face with Strawberry”). Thus, instead of understanding, he gives free reign to the powers of sensation, instinct, and chance. He does not lead the inquiry into the nun’s rape; he stumbles onto its culprits by chance. Thus it is to this figure of authentic virtue, for whom nothing can be discussed, that truth will be revealed: the factual truth of the identity of the rapists and the spiritual truth of forgiveness. The work of negativity in the nightclub sequence here finds its true meaning: to represent the pure immediacy of engagement, which is not a positivity but a lack of distinctness between self and exteriority, a total passion totally experienced instant by instant. Ferrara translates this passion in terms of unconsciousness and inebriation.

The few trembling steps taken by Kathy as she leaves the vampire orgy in The Addiction correspond to the blind stagger of L. T. leaving the nightclub. The figurative elaboration of The Addiction is inverse and complementary to that of Bad Lieutenant. The theoretical consciousness of the student who rationally analyzes historical reality—the somatization of which corrupts her organically to the point of transforming her into the ultimate, unassimilable scrap heap, a scumbag retching from the misery of having imbibed every imaginable anguish right down to the dregs—corresponds to L. T.’s psychic repression, which cuts him off from reality so that he can stay immersed in the evil he has absorbed via huge doses of crack and heroin. The unchanging L. T. can only disappear through magical sleight of hand; he is all or nothing. His death solicits neither agony nor becoming. Death does not come for him dramatically; it simply happens, with no great show. Hence the immense urban billboard at the foot of which, we assume, L. T. gets rubbed out: “It All Happens Here.” Complementarily, after being turned into a vampire by the Vietnam images, Kathy in The Addiction lives out her torment like an interminable anguish. She disintegrates from within, losing her teeth, her flesh, and even her gestures. On the sidewalk she metamorphoses into a deformed bag lady, bathing indistinctly in her own blood as well as the blood of her victims, a filthy scrap almost indistinguishable from the stretcher on which she is carried. But even this “thing” does not disappear; just this side of formless, Kathy returns again and always, like an insoluble problem. She returns as a sick person on a hospital bed, blessed when the rays of grace shine down on her; damned when the vampire suddenly halts the process, in repose after receiving the last rites; dead and gone when her name appears on a gravestone; and, finally, as a ghost at the cemetery. In contrast to L. T. in Bad Lieutenant, Kathy does not enjoy the relative luxury of a gradual disappearance. In a protracted, terrifying trajectory, she experiences every form of self-alteration and self-annihilation, abandoning along the way the remains of a false ego-integrity—the kind of integrity that western civilization thinks of as mental health but whose narcissistic, cruel, and morbid character the film has unmasked. Where L. T. wants to see nothing, Kathy wants to understand everything; where L. T. implodes, Kathy dissolves herself—two inverse and complementary somatic economies that render the same sacrificial logic.