I lay low for a while. There was nothing I wanted to show to an audience. I just wanted to rest and think. The ideal place to do that was Switzerland, and the ideal company was my son. By now he didn’t want to be called Zowie, but Joey. He was reaching adolescence; to become an adult he had to get rid of the burden of being the son of Bowie. It was stupendous watching him develop his own personality.

In Switzerland I reconnected with some more of my pupils: Queen. Freddie Mercury and I had met in the late ’60s at a flea market when we were nobodies. Things had changed plenty for everyone.

We started improvising in the studio and came up with “Under Pressure.” We knew it would be a hit, but I gave them the rights. It wasn’t an altruistic decision: I just didn’t want MainMan to make the money.

My extended rest period allowed me to reconnect with two people I had been far away from: my mother and Terry. She was happy to see me again; since my father died we hadn’t spent much time together. With my brother things were harder: he’d attempted suicide, throwing himself from a window at Cane Hill. When I went to visit him, he seemed pleased, but it was hard for me to look into his prematurely aged eyes. They seemed like hostages of his terrible illness, imploring me for some kind of aid I couldn’t supply.

I DON’T KNOW HOW MUCH OF IT IS MADNESS. I BELIEVE THAT THERE’S A TERRIBLE STORE OF EMOTIONAL AND SPIRITUAL MUTILATION IN MY FAMILY THAT HAS TAKEN HOLD OF ME IN DIFFERENT WAYS OVER THE YEARS.

But there was still the hope and consolation of being able to help my son. After he spent some days being ignored by Angie and her then lover during a visit in 1984, he decided not to see her any more. Coping with the lack of maternal love was something he would have to overcome on his own, but I, for my part, was not going to fail him.

At last the moment arrived to take complete charge of my career. When my debt with MainMan had been liquidated and my contract with RCA rescinded, I got ready to make up for lost time and money. Freddie Mercury had promised to be a go-between for me and his label, EMI, and I needed a record to seduce them with. I knew who I wanted at my side. Nile Rodgers had blown up playing funky music with his band Chic and then distinguished himself as a producer. I made it clear to Nile that I wanted to make hits. And we did. EMI was thrilled with the album Let’s Dance, and I received $17 million as an advance! The tour we embarked on, Serious Moonlight, was impressive: sixteen countries, ninety-six concerts, two and half million tickets. We filled stadiums night after night. Most of those fans had just discovered me through songs like “Let’s Dance” or “Modern Love,” which came accompanied with video clips that I had supervised down to the last detail. Few of them had heard of Brian Eno or Kraftwerk. Of course there were those who accused me of having gone commercial, as if my only function in life were to create the music they needed. But I was as happy as a kid to be on the front lines of pop.

My next album was Tonight. While I was out promoting it, I received the painful news that Terry had killed himself. He escaped from Cane Hill and lay down on the train tracks to end his suffering. I had just turned thirty-eight.

I decided not to go to his funeral. I didn’t want to turn my brother’s death into a show and be forced into the role of suffering superstar. I sent a crown that said,

YOU’VE SEEN MORE THINGS THAN WE CAN IMAGINE, BUT ALL THESE MOMENTS WILL BE LOST, LIKE TEARS WASHED AWAY BY THE RAIN. GOD BLESS YOU.

The press crucified me: I was a cold being who had turned his back on his family and abandoned his brother for years. Who were they to know what I felt? Where were they when Terry began to suffer? Did they have any idea how frustrated I was each time I saw him and realized that I was losing him little by little?

That wasn’t enough for them. Airing out David Bowie’s dirty laundry had become a lucrative activity. After Terry died they started digging, and all my family’s mental problems came to light. That was terribly painful, even more so when I found out that people I cherished, like Tony Visconti or Lindsay Kemp, had cooperated with the authors of those books. I felt betrayed. Anybody in my vicinity could play the game of making me into an amusement park attraction.

That was the price of being a global pop star.

But I wasn’t going to disappear down a hole. In 1985 I participated in the solidarity concert Live Aid in Wembley Stadium. I gave up part of my performance time to show a video about famine in Ethiopia, and the donations picked up. I dedicated “Heroes” to Joey and all the children of the world.

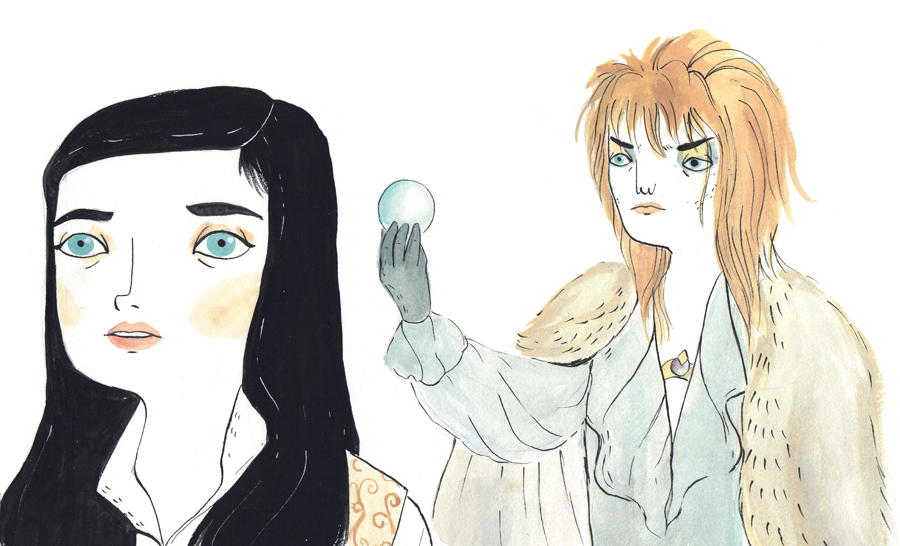

That same year I acted in the movie Labyrinth. Since so many people thought I was a heartless monster, I decided to become one, and I delighted in being the villain in a children’s story.

I also appeared in Absolute Beginners, set in the 1950s, in which I played a ruthless publicist.

In 1987 I went back into the studio and recorded Never Let Me Down. The result bored me so much that I thought about quitting and dedicating myself to my other great passion, painting. Escaping into my work, though, I kept touring and prepared what the times called for, the most dazzling spectacle possible: the Glass Spider tour. It featured an enormous spider of glass fiber, blinding lights, and dancers descending the threads. The money it made was only comparable with the colossal boredom the musicians and I felt.

I LOVED THE MONEY I WAS MAKING AND IT WAS OBVIOUS THAT TO KEEP ON MAKING IT I WOULD HAVE TO GIVE PEOPLE WHAT THEY WANTED. BUT I WAS DRYING UP AS AN ARTIST.

In October of that year came one of the bitterest episodes of my life as a star. Wanda Lee Nichols, a girl who had come on the tour with us and with whom I had gone to bed, accused me of rape. The jury rejected her accusation, but it outlined another lesson: I was a profitable star and was vulnerable to this kind of accusation. My nights of continual conquest had to stop.

Once that odious tour was over, we burned the enormous spider and felt liberated. The show was over, and the musicians went home to their families.

Me, I’d reached the goal I laid down for myself in 1983: I would never have to worry about money again. But the price was that I’d lost interest in creating. And although for a while I was with Melissa Hurley, nineteen years younger than I, something didn’t fit. Deep down, I continued feeling alone.