Annotations for Ecclesiastes

1:2 Meaningless! The Hebrew term signifies “a mere breath.” The theme of futility is found in numerous literary pieces in the second millennium BC. It is expressed in Gilgamesh’s affirmation that whatever mankind does is “wind.” The same word used by Gilgamesh is used in other texts to describe the way the world was regulated by the gods. The theme is worked out by discussing how all of the great deeds of the heroes of old amounted to nothing.

Modern readers are inclined to read statements like this through the lens of existential pessimism, amounting to a statement meaning “life is not worth living.” If the Teacher is prefiguring stoicism, however, his point is not so much on the “lack of meaning in everything that is” and more on “meaning is found elsewhere.” The stoic objective is not existential despair, but the devaluing of things to which most (nonphilosophers) assign value, so that the real value of really valuable things (virtue and philosophy for stoics, fear of the Lord for Ecclesiastes) can be properly demonstrated. An adequate English word for translating this concept is elusive, but it is the opposite of ultimate self-fulfillment.

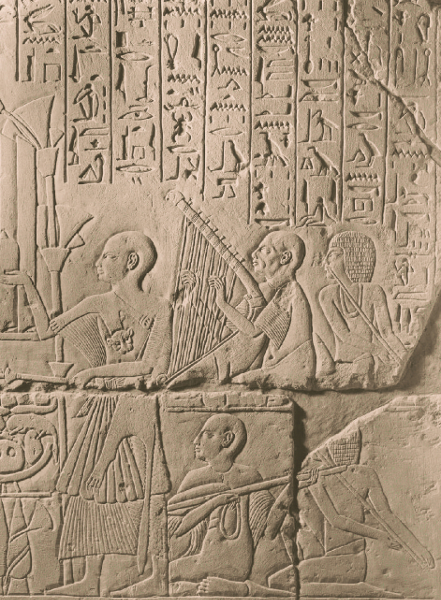

1:6 The wind blows. The monotony of the cycles of nature is a metaphor for the failure of human activity to accomplish anything, as each generation arises and then goes to its death. This sentiment appears in the Egyptian Harpers’ Songs as well: “Water flows downstream, the north wind blows upstream [since in Egypt the Nile flows north to the Mediterranean], and likewise everybody goes to his hour.”

1:8 All things are wearisome, more than one can say. More lit. “All things are weary; no one is able to speak.” This sentiment—that there is nothing new to report and no new maxims to give—strongly echoes the “Complaints of Khakheperresonb,” an Egyptian text composed in the Middle Kingdom period (c. 2055–1650 BC). In this text, the sage laments, “Would I had unknown phrases, / maxims that are strange, / Novel untried words, / Void of repetitions; / Not maxims of past speech, / Spoken by the ancestors.” He further insists that “One who has spoken should not speak,” in a manner reminiscent of Ecclesiastes’ claim that no one is able to speak.

1:9 there is nothing new under the sun. For Khakheperresonb (see previous note), all that people do under the sun is a mere “imitation of the past.”

1:11 No one remembers the former generations. This outlook rejects what seems to have been an obsession with ancient Near Eastern monarchs: the desire to create eternal monuments that would preserve their names through all generations. Of course, any educated Israelite would have known of the great stone inscriptions of Egyptian pharaohs. Perhaps the futility of this quest was already evident. There had already been examples of Egyptian monuments being buried in the sands, and not a few pharaohs had simply chiseled out the names of predecessors, as Thutmose III had done with many of Hatshepsut’s inscriptions. An Egyptian text known as “Berlin Papyrus 3024” laments that those “who build in granite and who hew out chambers in pyramids” are soon forgotten, and one of the Egyptian Harpers’ Songs wryly observes that even those who were once gods (i.e., the pharaohs) lie forgotten in their tombs.

2:8 harem. The Hebrew term here is usually taken as a designation for concubines. However, although that would not be an unusual claim for a king to make, the word is obscure and occurs only here, so its meaning is uncertain (see NIV text note). An alternative suggestion is that the Hebrew word should be translated “treasure chests.”

2:18 I hated all the things I had toiled for under the sun. Ecclesiastes laments that the wealth people acquire in their lifetimes of hard labor is simply passed on to others, who may be incompetent or unworthy of the bequest (vv. 18–26). This idea also has parallels in the Egyptian Harpers’ Songs: “Their property has been given to others. They are gone.” A common claim about ancient Near Eastern culture is that they believed that one in some sense lived on via the lives of their children, such that to die childless was considered a great calamity. There is some truth in this, as indicated by the Israelite concern to keep real property within a single family line, but one should not assume that ancient peoples were unable to reflect critically on such notions.

3:1 a time for everything. In further reflections on human mortality, Ecclesiastes asserts that because we are creatures of time and occasion, we must live in harmony with the ebb and flow of life (vv. 1–8). Any attempt to find a philosophy of time or of history in these verses should be abandoned; this text is about coming to terms with the realities of life, not about cyclical versus linear time or such notions.

3:5 scatter stones . . . gather them. Stones were cleared away from a field so that it could be used for agricultural purposes. The gathered stones were sometimes set up as boundaries between fields. The scattering of such stones would suggest land claims being dissolved or altered.

3:19 the fate of human beings is like that of the animals. Some scholars are struck by the use of the term “fate” (Hebrew miqreh) here and suggest that it is comparable to the Greek terms moira (“fate”) and tyche (“luck”). This, in turn, implies that Ecclesiastes was influenced by Hellenistic thinking. However, miqreh shows no influence from Hellenistic culture. The Greek Moirai (“Fates”) are goddesses (whereas miqreh is not), and miqreh is used in Ecclesiastes not for luck or even for predestined fate, but simply for one’s final destiny, i.e., death (v. 19; 2:14, 15; 9:2, 3). The rejection of immortality in these verses has echoes in the Harpers’ Songs of Egypt. We should add that Ecclesiastes here challenges the kind of afterlife envisioned in something like official Egyptian theology, which in effect denied the significance of death. Ideas that eventually became a part of Christian theology of afterlife were not yet developed in this time.

4:12 A cord of three strands. This has a remarkable parallel in the Gilgamesh Epic, in which Gilgamesh encourages his friend Enkidu about the value of friendship: “Two men will not die; the towed boat will not sink, / a towrope of three strands cannot be cut.” Both texts speak of the security that two can offer one another and then use the analogy of a three-stranded rope.

5:1 Guard your steps when you go to the house of God. The Egyptian “Instruction of Ptahhotep” similarly warns against speaking rashly, and a Ugaritic inscription speaks of a fool who thoughtlessly offers prayers to his god without an appropriate sense of guilt.

5:2 God is in heaven and you are on earth. Scholars have noticed that this is somewhat similar to a passage in the Gilgamesh Epic, in which Enkidu tries to dissuade Gilgamesh from entering the perilous Cedar Forest, and Gilgamesh replies, “Who, my friend, can scale he[aven]? / Only the gods [live] forever under the sun. / As for mankind, numbered are their days; / Whatever they achieve is but wind!” His point is that since we are mortal, we might as well grab what glory we can get. Gilgamesh’s words express the pagan ideal: mortals are doomed to suffering and death, but they can give value to their lives through heroism. Ecclesiastes begins with the same premise, but moves in a different direction: Mortals are weak and perishing, and this should drive them to understand the real meaning of the fear of God.

5:3 Dreams in the ancient world were thought to offer information from the divine realm, and were therefore taken seriously. Some dreams, those given to prophets and kings, were considered a means of divine revelation. Most dreams, however, ordinary dreams of common people, were believed to contain omens that communicated information about what the gods were doing. The information that came through dreams was not believed to be irreversible, but could be a cause for concern, if not alarm. This verse would therefore best be read, “As a dream is accompanied by many worries, so a fool’s speech comes with many words.”

5:4 vow to God. Information concerning vows can be found in most of the cultures of the ancient Near East, including Hittite, Ugaritic, Mesopotamian and, less often, Egyptian. Vows are voluntary agreements made with deity. The vows would typically be conditional and accompany a petition made to a deity. They were commitments to God in which the worshiper promised to undertake a certain action (generally of a ritual nature) if God answered their request. The swearing of an oath was considered a very serious matter in ancient Israel as well as throughout the ancient world. An oath is always sworn in the name of a god, which places a heavy responsibility on the swearer to carry out its stipulations, since he would be liable to divine, as well as human, retribution if he did not. Oaths were used in legal proceedings (see note on Ex 22:11) and for political treaties and covenants (see note on Dt 6:13).

5:6 temple messenger. There is no other Biblical reference to this office, but presumably it refers to a temple official whose job was to make sure that worshipers had fulfilled their vows.

5:13–17 The ideas presented here are similar to those in a late second-millennium BC text from Emar, a site on the Euphrates River in Syria. In the text, a father advises his son to be frugal and prudent, so as to acquire wealth. The son responds that humans, like the beasts, must die, and he wonders what value his father’s possessions will be to him when he dies. He says, “Father, you have built a house. You made [its entrance] high, with a storeroom ten cubits large.” The son’s point is that hoarding does not make for a happy life as death approaches.

5:17 eat in darkness. If one works in the fields from sunrise to sundown, then both breakfast and supper are eaten in the dark.

6:3 does not receive proper burial. Many ancient peoples believed that the spirit of a person who did not receive proper burial wandered restlessly. An old Sumerian poem of Gilgamesh says, “ ‘Did you see the one whose shade has no one to make funerary offerings?’ ‘I saw him. / He eats scrapings from the pot and crusts of bread thrown away in the street.’ ” Such notions do not seem to be present here in Ecclesiastes, however. Instead, the main concern is the simple lack of dignity and propriety in not receiving a funeral or not having children who care enough to bury you.

6:6 all go to the same place. See the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld.”

7:1 fine perfume. Banqueters in the ancient world were often treated by a generous host to fine oils that would be used to anoint their foreheads. An Assyrian text from Esarhaddon’s reign describes how he “drenched the foreheads” of his guests at a royal banquet with “choicest oils.”

7:6 crackling of thorns under the pot. The thin wood of thornbushes produces a lot of noise that draws attention as it bursts quickly into flame. However, it makes very poor firewood, since it has no lasting heat or sustained cooking ability.

7:13 straighten what he has made crooked. In the ancient Near East, the pious were constantly baffled about what the gods were doing and why they were doing it. In a Sumerian “Hymn to Enlil,” the poet says, “Your immensely clever deeds are dismaying, their meaning is a twisted thread that cannot be separated.”

7:14 When times are good, be happy. It may strike us as odd that acute awareness of the brevity and severity of life should prompt us to enjoy ourselves when the opportunity presents itself, but this is a major feature of the Egyptian Harpers’ Songs as well. When times are good. Lit. “On a good day.” The expression “a good day” is used in the Harpers’ Songs to describe a time when things are going well and one ought to have some fun. At the same time, Ecclesiastes is not simply repeating the maxims of Egyptian wisdom. The focus on enjoying life in the context of patient submission to the circumstances in which God puts us (“God has made the one as well as the other”) is distinctive to Ecclesiastes.

7:16 Do not be overrighteous, neither be overwise. This attitude is in contrast with much of the advice of the classic wisdom teaching of the ancient world, which taught precisely that prudence and piety does protect us from harm. In the service of most of the gods, rituals satisfied the needs of the gods, and that was all that mattered. The gods could not be overfed, and there was no such thing as too much care of them. The Egyptian “Instruction of Any,” e.g., says, “Observe the feast of your god, / And repeat its season, / your god is angry if it is neglected.” It would be a mistake, however, to take Ecclesiastes simply as a cynical piece of antiwisdom. The exhortations here stem from a conviction that all persons are sinful (vv. 22, 29) and that all attempts to impress God with personal piety fail. Also, Ecclesiastes drives the reader to a more profound understanding of the fear of God than that reflected in the external piety of the Egyptian admonition.

8:2–3 Advice concerning how to conduct oneself as a courtier is expected in wisdom literature, since its primary function was training future palace functionaries. Ecc 8 exhorts the reader to be properly submissive to authorities. Similar exhortations to obedience and proper decorum before rulers can be found in other ancient literature. The “Instruction of Ptahhotep,” e.g., teaches: “If you are in the audience chamber, / Stand and sit in accordance with your position, / Which was given to you on the first day. / Do not exceed (your duty), for it will result in your being turned back.” Ecclesiastes by no means supposes that government always works properly (vv. 11, 14), but even so, it exhorts people to behave respectfully toward authority, since it is both safe before the king (v. 3) and right before God (the “oath” of v. 2).

8:11 sentence for a crime. Israel shared a common legal tradition with the rest of the ancient Near East concerning criminal punishment. The most common penalties in the Bible were stoning, death by fire, and mutilation. Ancient Near Eastern sources (e.g., the Code of Hammurapi and the Middle Assyrian Laws) occasionally mention the methods of punishment, which included drowning, mutilation and impalement. Imprisonment was not used as a punishment for crime, though there were debtors’ prisons and political prisoners. Additionally, prisons would be used to detain those awaiting trial.

9:5 reward. The Hebrew term probably refers to the benefits of life, in which the dead cannot partake. The dead cannot enjoy any of the things that are considered blessings in this life. Beyond that, this also indicates the Israelite belief that there was no heavenly reward for a life of faith or good works. They believed that God’s justice was carried out in this life rather than accounts being settled in the afterlife. See the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld.”

9:7–9 These verses include some of the most remarkable parallels between a Scriptural text and other ancient Near Eastern texts found anywhere in the Bible. The “Song from the Tomb of King Intef,” from the Egyptian Harpers’ Songs, confronts human mortality and offers the following advice: “Put myrrh on your head, / Dress in fine linen, / Anoint yourself with oils fit for a god!” Another of the Harpers’ Songs, “Neferhotep I,” has similar advice: “Take fine perfumes pleasing to your nostrils, with garlands, lotuses, and berries at your breast, with your sister, who is in your heart, happy at your side” (“sister” here refers to one’s wife). Another strikingly similar text is in the Old Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, where the hero laments over mortality to an ale-wife, and she gives him this advice: “When the gods created mankind, / For mankind they established death, / Life they kept for themselves. / You, Gilgamesh, let your belly be full, / Keep enjoying yourself, day and night! / Every day make merry, / Dance and play day and night! / Let your clothes be clean! / Let your head be washed, may you be bathed in water! / Gaze on the little one who holds your hand! / Let a wife enjoy your repeated embrace!” Our three different sources—Babylonian, Egyptian and Israelite—have essentially the same message: “In light of the brevity of life, enjoy yourself!” This, of itself, may not be too remarkable, but the specific nature and sequence of the advice (feasting, wearing clean clothes, anointing with oils and perfumes, and enjoying one’s wife) suggests a common wisdom tradition.

9:8 clothed in white. Scholars have understood the color white to symbolize purity, festivity or elevated social status. In both Egypt (Story of Sinuhe) and Mesopotamia (Gilgamesh Epic), clean or bright garments conveyed a sense of well-being. In addition, the hot Middle Eastern climate favors the wearing of white clothes to reflect the heat.

9:11 chance. In ancient Near Eastern belief, fate was written on tablets, and those who controlled them controlled the destiny of the universe. If they were in the wrong hands, there was chaos in the world. In one Mesopotamian myth, a chaos creature (Anzu) stole the tablets of fate, which caused quite a stir within the divine community until he was killed. The Israelite concept of fate or chance was different than that of Mesopotamia. Instead of viewing something as a random happening (Fate), they would consider it simply an unexpected event (serendipity). “Time” and “Chance” are not presented here as two separate contingencies, but as a single factor. A “well-timed coincidence” can occur in any situation, and alter what would have been considered an assured outcome.

9:12 fish are caught . . . birds are taken. Although Ishmael and Esau were known as hunters, hunting was not a typical vocation in Israel except to confront hunger or the predominance of wild animals that caused danger to flocks. In both Assyria and Egypt, however, there are numerous wall reliefs depicting royal hunting scenes. Hunting is also implied for Solomon’s court (1Ki 4:23). Fishing, like hunting, was not mentioned as recreational in ancient Israel. The book of Job describes fishing by spear or harpoon (Job 41:7) or by hook (Job 41:1–2; see also Isa 19:8). Like hunting, fishing was often the basis of metaphors, primarily as a figure of God’s judgment on individuals or nations.

10:2 right . . . left. While there is no doubt that the right side was considered the place of honor and the most protected position, there is no indication that there was something negative or inherently weak or evil connected to the left side, either in the ancient Near East or Israel. It was secondary in honor and an unexpected direction from which to attack. The fool chose the path of vulnerability and lower status.

10:7 slaves on horseback . . . princes go on foot. Aspects of this passage have interesting parallels in the Egyptian texts. As Ecclesiastes complains of slaves on horseback, so the “Complaints of Khakheperresonb” declares, “He who used to give commands is (now) one to whom commands are given.” The Admonitions of Ipu-wer similarly complains, “Indeed, princes are hungry and perish, / Servants are served.” These Egyptian texts are not in all respects the same as Ecclesiastes; they tend to focus on the general lawlessness in society during times of political instability in Egypt, whereas Ecclesiastes is concerned more universally with the absurdities of human life. Still, both reflect a common way of describing a world gone wrong.

10:8 digs a pit. Designed to catch a large animal. With that purpose in mind, the pit was disguised, therefore making it possible that one could stumble into it himself. breaks through a wall. When a stone wall was dismantled, or when a breach was made in a wall for a gate, a farmer could unwittingly disturb a snake who had taken up residence among the cool stones.

10:9 quarries stones. The quarrying of rocks referred to here is probably not that done by professionals, because the other activities in vv. 8–9 are all normal agrarian activities. The verb is used for quarrying, but is also used in more general contexts that deal with uprooting or taking something out. Alternatively, then, this line could refer to a farmer clearing stones from his field. Injury could come from dropped rocks, hernias or scraped arms. splits logs. The dangers inherent in splitting logs are easily recognizable. The ax head could fly off the handle or glance off the wood and result in serious injury.

10:11 charmed. The Hebrew word should not evoke cartoon-like images of swaying serpents hypnotized by pipe-playing swamis. Instead it refers to snakes against which incantations are ineffective. Snake charming was well known in both Mesopotamia and Egypt. Often the practice apparently served a religious purpose; a famous artifact from Crete is the “Minoan Snake Goddess,” a figurine dating to c. 1600 BC, depicting a woman holding aloft two snakes. She is apparently a priestess or goddess. Here in Ecclesiastes, however, snake charming is not a religious function, but a matter of personal safety.

10:20 a bird in the sky may carry your words. Stories of “little birds” who told secrets are found in Aristophanes’ The Birds, a classical Greek comedy, and in the Hittite Tale of Elkuhirsa. The Words of Ahiqar assert that a word is like a bird and that one who releases it lacks sense.

11:1 Ship your grain across the sea. There is debate about the meaning of this injunction. In context, it appears to encourage trade and commerce: One should diversify the investment in seven or eight directions (v. 2) in the certainty that eventually one’s investments will come back (“return,” v. 1). Other translations use some iteration of “Cast your bread upon the waters, for you will find it after many days” (ESV, NKJV; cf. KJV, NASB), which brings with it an interesting alternative interpretation. Akkadian texts on beer making have prompted the suggestion that Ecc 11:1 actually refers to brewing practices. These Akkadian texts indicate that dates and a type of bread were “thrown” into the “water” during the process of mixing ingredients for beer. In this interpretation, “you will find it” would mean that the bread will come back to you as beer; and in v. 2, “give a portion to seven” (ESV, KJV; cf. NASB, NKJV) would mean that you should share the beer with others so that in lean times the others will reciprocate. On the other hand, some argue that Ecc 11:1 refers to charitable giving by pointing to similar language in the “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq,” an Egyptian wisdom text from between the third and first centuries BC: “Do a good deed and throw it in the water; when it dries you will find it.” For all this, the actual context of Ecc 11:1 strongly suggests that it is concerned with trade rather than either beer making or charity.

11:9 Follow the ways of your heart. The exhortation that we should “be happy” in the context of facing the reality of death is similar to the message of the Harpers’ Songs. For example, the “Song from the Tomb of King Intef,” after mourning the fact that those who have built monuments before us are now silent in their crumbling tombs, urges the audience: “Hence rejoice in your heart! / Forgetfulness profits you, follow your heart as long as you live!” Similar teaching is found in the “Instruction of Ptahhotep” from the Middle Kingdom period of Egypt: “Follow your heart as long as you live, / Do no more than is required, / do not shorten the time of ‘follow-the-heart.’ ” The similarity of the Egyptian and Biblical exhortations to “be happy” and “follow” the heart is striking, although the Bible is distinctive for linking this concept to a fear of God.

12:3 keepers of the house. Could refer to male servants, common as house slaves throughout the ancient Near East, but often they were people in authority (such as Joseph’s role in Potiphar’s house, Ge 39:2–4).

12:1–14 Ecclesiastes concludes with several exhortations to fear God in the face of our mortality (vv. 1, 6, 13–14).

12:1–7 Ch. 12 includes one of the most memorable passages in the book, the allegory of death as a failing household (vv. 1–7). Egyptian “Berlin Papyrus 3024” likewise has a poem on the end of life; it is named for its refrain, “Death is before me today.” It looks upon death as a release from suffering: “Death is before me today / Like a sick man’s recovery, / Like going outdoors after confinement.” One verse is similar to Ecc 12:5 in describing death as a return “home.” It reads, “Death is before me today / Like a man’s longing to see his home / When he has spent many years in captivity.” The apparent optimism about death in these lines is misleading. They reflect the weariness and pain of the aged dying, for whom death is a relief. Ecc 12:1–7 metaphorically describes the suffering and weakness of the body as death draws near.

12:9–14 Ecclesiastes ends with an epilogue reasserting both a balanced view of the importance of wisdom (vv. 9–12) and the main point of the book: one should fear God (vv. 13–14). The use of an epilogue in a wisdom text is also known from Egyptian literature; epilogues appear, e.g., in the “Instruction of Ptahhotep” and the “Instruction of Any.” As such, there is no reason to regard the conclusion to Ecclesiastes as a secondary addition to the text, as a number of scholars do, or to see it as a “correction” or contradiction of the gloomy realism of the rest of the book.