Maybe you have an interest-paying checking account but your balance keeps falling below the required minimum. That might cost you $10 or more each time. You’ll save money over the year by choosing free no-interest checking.

Maybe you have an interest-paying checking account but your balance keeps falling below the required minimum. That might cost you $10 or more each time. You’ll save money over the year by choosing free no-interest checking.Banking in the Internet Age

Good bankers are nice,

but great online services are even nicer.

When you look for a bank, you’re looking for services, convenience, and price. Your options are small banks, big banks, online banks, and credit unions.

Internet banks, with no actual buildings, and the online, or “direct,” services of traditional banks, are a huge win for savers (page 45). They pay top interest rates on savings accounts and certificates of deposit. Their checking accounts also offer higher rates.

Small, community banks win on personal service, both for individuals and small businesses. They usually charge lower fees and pay higher interest rates than big banks do. They’re also in a better position to restructure mortgages that are in trouble. Some of them specialize in trusts and other financial services for the well-to-do. I love community banks.

Big banks win on convenience, thanks to their wider network of ATMs, longer list of financial products, and better services online. They might even let you use your cell phone to pay your bills. But they kill you with fees.

Credit unions win on niceness, community feel, and caring about their members’ financial well-being. In general, they offer better interest rates and lower banking fees than the competition. If you can’t join through your employer, you might find one that serves your city or region. Anyone can join the Pentagon Federal Credit Union (www.penfed.org). For other possibilities, check the Web site of the Credit Union National Association (CUNA) at www.cuna.org; write to CUNA at P.O. Box 431, Madison, WI 53701; or call them at 800-356-9655. Some credit unions offer a limited fare: only checking accounts (known as share draft accounts), savings deposits, and consumer lending. Others also provide mortgages, credit cards, online banking, and stockbrokerage at a discount. Check that the credit union carries federal deposit insurance (see the National Credit Union Administration’s credit union directory at www.ncua.gov/data/directory/cudir.html). Around 3.5 percent of them still carry private insurance, which, as previous banking debacles show, can buckle under pressure.

Savings and loan associations used to specialize in mortgages, but that was many years ago. Now they’re like small or large banks, with similar services for consumers.

Banklike services can also be had at large brokerage firms through their asset management accounts (page 51). But those are best used as convenience accounts for investors. For everyday transactions, most people need a bank.

If you want a basic savings account, there are two ways to go: a traditional bank, where your money will earn a pittance; or an Internet bank, which will pay you more. That’s a no-brainer. Go online!

You open the account online and transact your business there. You can also access the account by mail or phone and speak to a service rep if you have a problem. The rules are simple: no fees, no minimum deposits, no complicated accounts, no bank lines, no time wasted driving back and forth to see a teller. And your savings will earn a lot more money.

You can link your Internet savings account to the checking account you already have at a traditional bank. That lets you move money back and forth with the click of a mouse. Consider having your paycheck deposited into your Internet savings account automatically. To pay bills, move some of that money into your checking account as needed. There might be a two- or three-day delay before the traditional bank credits your checking account with the cash, but so what? You’re earning interest on cash that would otherwise lie fallow. If you’d rather send your paycheck to your traditional checking account, set up an automatic savings arrangement. Have a fixed sum of money transferred to your Internet account every time your paycheck comes in.

Checking accounts are the next step for Internet banks. They’re in their infancy but are sure to grow. As with savings accounts, there are no monthly service fees, no minimum deposits, and high interest rates, compared with those paid by traditional banks. You get overdraft protection if you authorize a check for more than you have in the bank; your only cost is the interest you pay on the amount you borrow to cover the bill. There’s no delay when transferring money from Internet savings into Internet checking, so you can pay your bills immediately. The technology is a little different from that of online bill-paying at traditional banks. You don’t get a checkbook. Everything is paid electronically or with debit cards. Still, it’s easy and will earn you extra money on your funds.

At this writing, the majors include EmigrantDirect, EverBank, ING Direct, and UnivestDirect. Traditional banks that offer high-rate Internet-only savings accounts include First National Bank of Omaha (FNBO Direct), HSBC Bank (HSBC Direct), and Citibank (Citibank Direct requires you to have a Citi checking account too). High-rate savings are also available at certain brokerage firms such as E*Trade Financial and Charles Schwab. At this writing, free high-rate checking accounts can be had at ING Direct and HSBC Direct, with more to come.

Most Internet banks also offer a range of other banking services: certificates of deposit, Individual Retirement Accounts, mutual funds, credit cards, auto loans, mortgages, and home equity lines of credit.

Note that these are all pure Internet accounts. A Citibank Direct customer has to handle his or her business online (or by mail or phone) and doesn’t have access to the branches. But why would you want it? It’s easier to bank from home at whatever hour suits you. The service is as good as or better than you get from traditional banks. If your paycheck is deposited into your account automatically and you pay your bills online, you rarely have to visit a bank branch. This way of doing business also makes you a cheaper customer to serve, which is why you can earn higher interest rates.

Checking accounts and some of the savings accounts come with ATM cards. Internet customers of a traditional bank can use its ATMs free. ING Direct, which has no ATMs of its own, offers free use of Allpoint ATMs, found in stores and at smaller banks. At other ATMs, you pay the ATM owner $1.50 or $2 per transaction. The Internet banks all reimburse you for at least $6 in ATM charges every month, and sometimes more.

Some people worry that Internet banks are vulnerable to hackers. But banking environments have been highly secure. An Internet bank is no more vulnerable than the online bill-paying services of traditional banks, which millions of customers use. If a hacker broke into a bank’s database, the bank would reimburse you. If the bank goes out of business, your deposits are protected by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (look for the FDIC label on the banks’ Web sites or check it yourself on the FDIC Web site, at www3.fdic.gov/idasp, or call 877-275-3342).

Don’t confuse Internet banks with traditional banks that have simply moved their usual services online. The traditional banks still charge fees for various types of checking or savings accounts, require minimum deposits, and charge if you fall below the minimums. True Internet banks—the direct banks—ditch the service fees and pay high interest rates.

Don’t just drop in and wait to see someone who’s free. Avoid a long wait by making an appointment with the person in charge of opening new accounts.

Before going to the meeting, check the bank’s financial products and fees online or pick up the brochures that it stocks by the front entrance. Read them to see what services you might want. Make a list of questions.

At your meeting, go through your questions one by one. Ask for a list of the bank’s fees for various services, including all the costs associated with its checking accounts, savings accounts, and credit cards (they may also be listed online). Ask how long it holds checks you deposit before you have access to the money (page 56). If you write checks against your deposits too soon, you’ll be charged $20 or $30 for having nonsufficient funds (the bank calls it an NSF fee).

Explain to the banker the kind of customer you expect to be. How much money will be flowing through your checking account. What services you might need. Find out whom to call if you have a question or need some help. Talk about any loans you might want. A home mortgage or home equity line of credit? Money for starting a business? What does it take to get a lower interest rate on loans and a higher rate on savings?

Take the measure of the person you’re meeting with. Is he or she helpful? Knowledgeable about the bank’s products and services? Willing to answer your questions in detail? Ready with good ideas? Interested in getting your business? A banker who starts out gruff, impatient, vague, supercilious, or ill informed will not improve with time—and what is tolerated in one bank officer will be tolerated in others. Go to a place that makes a better first impression.

Compare the fees, interest rates, and services offered by at least two institutions—say, a big bank and a small one. Each represents a statement of business philosophy. High-fee banks are likely to charge even more in the future; low-fee banks are dedicated to holding down overt costs. Banks that pay high rates on savings have effectively announced that they’ll always be competitive; banks that pay low interest won’t be. Those are messages to pay attention to.

Don’t be swayed by the various types of investments the bank is selling. You can usually do better somewhere else. You should make your decision based on its banking services alone.

No need to wander through the wilderness, wondering which of a half-dozen checking accounts is best. If you’re a customer of a traditional bank, your choice hangs on a single test: what is the lowest average balance you will leave on deposit every month? If it’s small, get a checking account that pays no interest. To earn interest, you have to maintain an average of $2,600 on deposit, depending on the bank, according to the latest checking study by Bankrate.com, which surveys interest rates nationwide. (You can earn interest on as little as $1 if you use an online bank—see page 45.)

By law, banking institutions must use the average daily balance method of figuring your minimum balance. This takes the amount you have in your account each day and averages it across the entire month. If you keep $5,000 there for 29 days and on the 30th day write a $5,000 check, that month’s average balance would be $4,833. In arriving at your average daily balance, some banks will count both your checking and your savings deposits.

Some 218 small credit unions still gyp customers with low-balance accounting. Here, the credit union looks only at the lowest point in your account that month. If you held $5,000 for 29 days and then emptied your account, the credit union would call your monthly balance “$0.” You would earn no interest. Worse, you might pay a fee for falling below the minimum balance. Ask about low-balance accounting before deciding to join.

Besides interest rates and minimum deposits, look at the schedule of fees: monthly fees, fees for each check you write, fees for dropping below the minimum balance or bouncing a check, fees for checking your current balance, fees for using another bank’s ATM, and others. Don’t let your banker’s hand be quicker than your eye. A checking account might deliberately carry a low monthly fee or no fee at all in order to make it look cheap to price shoppers. But the bank might recoup by charging you extra for processing checks. Banks are required to give you a full list of fees. Ask for it before opening an account.

You want an account that pays the highest interest rate possible on the average balance you can afford to keep, while not breaking your back with extra fees. So look around. At GoodGuy Bank, your checking deposits might earn $75 a year. At BadGuy Bank, exactly the same account might cost $150 even counting your interest earnings. In general, smaller banks charge lower fees and require lower checking account balances than larger ones. Here’s an idea of what’s around.

No-interest checking. The majority of accounts require no minimum balance and charge no monthly service fee. Where monthly fees and balance requirements exist, they’re low. You earn no interest on the idle money in the account.

Interest-Paying Checking. You earn a wee interest rate on your idle balances—at this writing, less than 0.5 percent. There are usually no monthly fees if you maintain a minimum balance in the $2,500 to $10,000 range, depending on the bank. Otherwise you might pay $10 or so per month. At some banks, the amount of interest you earn and the fees you pay vary from month to month, depending on the size of your balances or the amount of business you do.

No-Interest Checking Plus a Bank Money Market Account. Why keep $2,500 on deposit earning 0.5 percent or less? Instead choose no-interest checking and park your $2,500 in the bank’s money market deposit account (page 219), where it will earn more.

Bundled Accounts. Your interest-paying checking account may be “bundled” with other banking services, such as discounts on loans or a quarter-point interest bonus on various savings deposits. You get the whole package for a single monthly fee or no fee at all, depending on the size of your combined checking and savings deposits.

Basic, Lifeline, Student, or No-Frills Checking. These accounts are for people who keep superlow average balances (as low as one penny) and write just a few checks a month. If there’s a fee, it’s small. The first 8 to 12 checks or withdrawals may be free, with fees of 35 cents or more for each check over the limit (if you write a lot of checks, you should be in regular checking). This simplified service is offered by about half the banks, although it may be restricted to students or the elderly.

Express Checking. You do all your banking business by personal computer, phone, and ATM. If you need a teller, you pay a fee.

It’s easier than ever to overdraw. You’re not only writing checks against your account, you’re also taking money from ATMs, making purchases with debit cards, and arranging for certain bills to be paid automatically every month. What’s more, the checks you write can be turned into digital images and sent to your bank for payment overnight. A supercareful person will get all these payments and withdrawals into the check register on time. But it’s easy to slip, and when that happens, checks may bounce. To avoid high bounced-check charges, set up one of these three backup systems:

1. Link to Your Savings Deposits. If you accidentally overdraw, the bank will take the extra money out of your savings—either regular savings or a money market deposit account. There may be a $5 or $10 fee for each transfer.

2. An Overdraft Line of Credit. The bank lends you money to cover the check or withdrawals. You pay interest as long as the loan is outstanding and, sometimes, an annual fee of $15 to $25. Some banks lend only in $50 increments, so if you write a check for $1 too much, you’ll have to borrow $50 to cover it. There may also be a transfer fee. Monthly repayments may be deducted from your account automatically.

3. Link to Your Credit Card. Overdrafts will be charged as a cash advance. You’ll pay a fee each time ($3 or so), plus the card’s high interest rate.

What About Bank “Courtesy Overdraft Protection” Plans? Your bank might advertise that it automatically covers overdrafts for accounts in good standing, up to a certain amount—say, $300. You’ll pay $20 to $35 for every item covered. The amount owed, plus fees, is deducted from your next deposit. Sometimes there’s an additional fee of $2 to $5 for every day that you don’t repay the loan. This “courtesy” is usually offered “free” as a part of the package, and you can see why. It makes a ton of money for the banks! Reject it. Instead, choose one of the three alternatives above.

A free account has no monthly maintenance fees, no per-check fees, and no fees for falling below the minimum balance. But there can be plenty of other charges: for ATM use, bounced or stopped checks, printing checks, balance inquiries, and a few other minor items.

Asset Management Accounts. These are for active investors who want an easy way to keep track of their cash. They generally combine a money market account (which doubles as an interest-paying checking account) with a brokerage account and a credit or debit card. With asset management accounts:

Some accounts offer an automatic bill-paying service and let you arrange to have your paycheck deposited electronically.

The minimum deposit for asset management accounts (including the value of your stocks and bonds): $1,000 to as much as $25,000. Annual fees run from zero to $125. These accounts are offered by a few big banks, brokerage houses, some mutual funds, and a few insurance companies. When you’re not with a bank, you may have to wait up to 15 days for the checks to clear.

Money Market Mutual Funds. These too are normally for investors. Rates of interest change daily but are usually higher than those on the banks’ interest-paying checking accounts. The funds that offer checking (about half of them do) charge lower fees than banks and zero for falling below the minimum balance. You can arrange to have your paycheck deposited directly. For more on money market funds, see page 220. Most won’t cash checks smaller than $100 or $250, so you’ll still need a bank account.

The drawbacks to using money funds as checking accounts: You may not have access to ATMs, deposited checks will be held for up to 15 days before you can draw against them, and you can’t get a line of credit.

At most traditional banks, you can pay your bills online—a huge convenience. You enter the names and addresses of the companies or people you owe money to. If it’s a company, include your account number. When the bills come in, you just call up your payee list, enter the amounts you owe, click, and pay. Payments to big companies usually go electronically. Otherwise the bank will mail a paper check, so you can pay a friend, a small business, your sister, anyone. The account can be programmed to pay certain bills automatically every month. You can also transfer money from one account to another. Some banks charge a fee for online bill paying, but most don’t.

Online bill paying is a godsend if (like me!) you hate balancing your checkbook. All your deposits and online payments show up on your computer screen when you access your account. That gives you a running daily tally of most of the money in your account. Occasionally an item you buy with a debit card might not register right away, so it’s worth checking those receipts against the sums debited from your account. You also have to keep track of the few paper checks you might still write by hand. As long as you can keep a cash cushion in your account, however, online banking makes checkbook balancing obsolete. Whew!

Online payments may also save you money. Some companies charge $1 to $5 a month for mailing paper bills. You avoid this fee if you arrange to have the bills paid automatically through your bank account.

One warning when you pay online: The debit will show in your checking account immediately, but the actual payment won’t be sent right away. Some banks make the payment in a couple of days; others take as long as a week. If your bank delays sending out checks, pay your bills as soon as they arrive. If you hold your bills for a couple of weeks and the bank adds a week for processing, your payment may arrive late and incur a late charge. (Even if your bank takes a week to pay, by the way, it will probably credit your checking account with interest until the cash actually leaves the account.)

Money management online: The next step for online banking will be personal financial management. Some banks already show you all your accounts, including your mortgage, on a single page. They may break down your expenses by tax category or provide a budgeting tool. You can even link to your other financial institutions, such as brokerage or mutual fund firms, and manage those accounts through your online bank portal. Other possibilities: an online check register where you can enter checks you write by hand, thus keeping your bank balance up to date; daily downloading of your credit card charges, so you’ll always know how much of your income you’ve spent that month; online spending alerts if you go over your budget for certain types of expenses; and similar options.

Can you switch banks? Changing banks gets more complicated once you’ve established online bill-paying accounts. But don’t hesitate if your bank has been giving poor service or hiking your fees. Some banks have “switch kits” to walk you through the procedures. An increasing number of banks will even handle the switch for you, to make it easier to move.

How about paying bills online through each company’s individual Web site? Why would you bother? You’d have to click on several sites and remember a pile of passwords. When you pay through your bank, it’s just one password, all the time.

How about letting utilities and other regular billers take what they’re owed from your bank account automatically every month? Absolutely not. It there’s an error, it takes a while to get your money back. If you cancel the payments, the companies may keep drawing on your account for several months more. Set up these automatic payments yourself, through your bank account online. That lets you stop payments at any time.

How about paying through a dedicated bill-paying service? No point. These services charge monthly fees, while your bank’s service is usually free.

How safe is banking online? Plenty safe. Banks are extremely careful about their security systems. The breaches you hear about involve mostly credit or debit cards and corporate or government data, not bank data. Millions of people successfully bank online through traditional services and Internet banks. If a hacker gets into a bank system and steals your money, the bank will pay. If a fraudster steals your PIN and writes himself a giant check, you’re liable for no more than $50, as long as you tell the bank right away.

Internet banks don’t send out paper statements. Traditional banks urge you to cancel your paper statements and let the computer keep track of everything for you. One problem: your online account may show transactions back for only 6 months (online banks may show 12 months). The bank can retrieve older payments, but it will take a few days and you may be charged a fee. That’s a problem if there’s an audit or transactions are questioned. If you have a traditional account, I’d suggest that you keep paper statements and file them for at least 6 years. At an Internet bank, I’d print out or download a statement every month and file that.

Join the crowd. Everyone’s screaming. That’s one of the reasons they’re moving to purely Internet banks—to avoid the fees.

If you prefer traditional banks, you may be able to cut your costs. When you opened your checking account, you probably looked only at how much interest you could earn. Now you know that the best account is the one that carries the lowest fees.

To find that account, start by analyzing your recent bank statements. Circle every fee to see how much you’re spending each month (it could be as much as $300 a year) and list what all the fees were for. Then make a written summary of the way you use the account. How many checks do you write per month, and what do they cost? How often do you use a teller or ATM (and does your bank charge you for it)? How low does your monthly balance go? How many incidental services do you use? How large are your savings deposits there? How much interest have you earned on your interest-paying checking, and does it exceed the fees you pay?

Armed with this information, sit down with a bank employee and say that you’d like to find ways of lowering your fees.

Maybe you have an interest-paying checking account but your balance keeps falling below the required minimum. That might cost you $10 or more each time. You’ll save money over the year by choosing free no-interest checking.

Maybe you have an interest-paying checking account but your balance keeps falling below the required minimum. That might cost you $10 or more each time. You’ll save money over the year by choosing free no-interest checking.

Maybe you write so few checks that you can manage on a no-frills account.

Maybe you write so few checks that you can manage on a no-frills account.

Maybe your fees will drop if you keep more deposits in the bank. If you have a CD somewhere else, move it to this bank when it matures.

Maybe your fees will drop if you keep more deposits in the bank. If you have a CD somewhere else, move it to this bank when it matures.

Maybe you’re tapping your account through another bank’s ATM. That usually costs more than using your own bank’s machines. Big banks have ATMs everywhere. If you’re at a small bank, see if it has a “selective surcharge” deal that lets you use the ATMs in a particular network free.

Maybe you’re tapping your account through another bank’s ATM. That usually costs more than using your own bank’s machines. Big banks have ATMs everywhere. If you’re at a small bank, see if it has a “selective surcharge” deal that lets you use the ATMs in a particular network free.

Maybe you pay ATM fees to check the balance in your account because you don’t keep your check register up to date. You might even find yourself overdrawing month after month. Switching to online banking could save you money because you’d always know how much cash you had on hand. (So would keeping up your check register, but I don’t want to ask too much.)

Maybe you pay ATM fees to check the balance in your account because you don’t keep your check register up to date. You might even find yourself overdrawing month after month. Switching to online banking could save you money because you’d always know how much cash you had on hand. (So would keeping up your check register, but I don’t want to ask too much.)

Maybe you haven’t noticed that your account limits the number of debits you’re allowed each month. You can eliminate overage fees by staying within the rules.

Maybe you haven’t noticed that your account limits the number of debits you’re allowed each month. You can eliminate overage fees by staying within the rules.

Maybe it costs less to pay by debit card or automatic electronic transfer than to pay by check. Automatic transfers work for any regular monthly payments: mortgage, rent, auto loan or lease, condo maintenance, life insurance premiums, utility bills, and regular monthly investments.

Maybe it costs less to pay by debit card or automatic electronic transfer than to pay by check. Automatic transfers work for any regular monthly payments: mortgage, rent, auto loan or lease, condo maintenance, life insurance premiums, utility bills, and regular monthly investments.

Maybe your bank offers online banking from your home computer at a lower price than banking in person or by mail.

Maybe your bank offers online banking from your home computer at a lower price than banking in person or by mail.

Maybe it’s cheaper to have your paycheck deposited electronically or to accept a checking account statement in lieu of canceled checks.

Maybe it’s cheaper to have your paycheck deposited electronically or to accept a checking account statement in lieu of canceled checks.

It’s doubtlessly cheaper to switch to a credit union if there’s one you can join (page 44) and it has the services you want.

It’s doubtlessly cheaper to switch to a credit union if there’s one you can join (page 44) and it has the services you want.

For sure, it’s cheaper to buy checks from a commercial check printer rather than through your bank. Three to try: Checks in the Mail (www.citm.com or 800-733-4443); Deluxe Checks (www.deluxe.com or 800-335-8931); and Checks Unlimited (www.checksunlimited.com or 800-210-0468).

For sure, it’s cheaper to buy checks from a commercial check printer rather than through your bank. Three to try: Checks in the Mail (www.citm.com or 800-733-4443); Deluxe Checks (www.deluxe.com or 800-335-8931); and Checks Unlimited (www.checksunlimited.com or 800-210-0468).

1. Banks have to tell you 15 or 30 days in advance when they’re raising a fee, depending on the product. But the notice might be written in fine-print Sanskrit, which means that you’ll probably throw it away. Prudence dictates that you read all bank notices and get a translation when you don’t understand them. If you don’t bother, check your statements periodically for new fees that you may have missed.

2. Banks charge wildly different fees! Your bank may be expensive compared with the competition. You might be able to cut your fees in half simply by comparing prices and switching to a cheaper bank. Small banks and credit unions usually charge the least. But a few big banks have eliminated all nuisance fees for customers who keep balances of $2,000 or more.

How to pay the lowest fees the easy way: choose an Internet bank. Or have I said that before? Also look at credit unions and small community banks.

A good banker should be able to answer all nine of the following questions. If you get a blank look—or a gentle drift of oral fog—ask again. You’re entitled to a clear and simple statement that makes sense. If you don’t understand what the banker is saying, don’t blame yourself. Blame the banker, who probably doesn’t have all the facts and is covering up. If you had $10 for every “expert” who wasn’t, you’d be rich.

1. Ask: With interest-paying checking, what does the banking institution pay interest on? By law, it must pay on the money that’s in your account at the end of each day. That’s “day of deposit to day of withdrawal.” But some pay on each check from the day you put it in. Others pay only on the collected balance, which means you get no interest until the check has provisionally cleared. That usually takes one or two days but sometimes more.

Some banks advertise more than one rate, depending on the size of your deposit. They might pay 1.5 percent on balances up to $1,000 and 2.7 percent on larger amounts. But what exactly does that mean? There’s a good way and a bad way to figure it.

Say, for example, that you deposit $2,500. You might get 2.7 percent on the whole amount, usually called a tiered rate. That’s good. Or you might get 1.5 percent on the first $1,000 and 2.7 percent only on the remaining $1,500, usually called a blended rate. That’s bad. In fact, it’s a clip job. Avoid blended rates.

2. Ask: What is the penalty for falling below the minimum balance? The fee might exceed the interest that your account is likely to earn. If you can’t be sure of maintaining the minimum balance, switch to an account with a lower minimum—for example, a no-interest-paying account.

3. Ask: What fees might you have to pay with this account? You should get a list, including charges for maintaining the account, processing checks, bouncing checks, using an automated teller machine, using a human teller, buying checks printed with your name and address, confirming your current bank balance, buying certified checks, stopping payment on a check, transferring funds by telephone, and depositing checks that turn out to be no good (called deposit item returned—see page 58).

4. Ask: Will the bank reduce the interest rate on your loans if you keep a checking account there and allow the loan payments to be deducted automatically?

5. Ask: If you invest in a certificate of deposit or take out a loan, will the bank eliminate the fees it charges for your checking account? Most institutions give their better customers special breaks. Some tie-in deals, however, are not worth having. You might save yourself a quarter point on an auto loan by taking out a certificate of deposit. But that’s no bargain if cheaper auto loans are available somewhere else.

6. Ask: If you sign up to have your paycheck deposited directly in your account, will the bank waive the fee? Some banks offer lower monthly fees or free checking for direct deposits.

7. Ask: What’s the cost of protecting yourself against a bounced check? Get all the fees for overdraft protection—whether linked to your savings account, credit line, credit card, or the bank’s so-called courtesy (or high-fee) plan.

8. Ask: When you deposit a check, how long do you have to wait before being able to draw against the funds? By law, your bank has to tell you exactly what the rules are. People with new accounts usually have to wait longer than people whose accounts have been at the bank for two or three years.

9. Ask: If you choose paperless statements, how long does the bank keep the record of your past transactions (for tax purposes, you want seven years) and what does it cost to retrieve your past records?

There you stand, like a kid with his nose pressed against a pet store window. Your money is romping behind the glass and you can’t get at it. Any checks you deposit may be held by your bank for a specified number of days. Fortunately, most institutions offer one-day clearance for almost all checks deposited to well-established accounts. But they’re allowed to hold checks longer and you need to know the outside limits.

Under federal law, banking institutions normally must give you access to at least $100 of your deposit on the next business day (not counting Saturday, even if the bank is open) and must clear the rest of your deposit on a specified schedule (with some quirky conditions here and there). All the following limits apply to checks deposited to your account before the bank’s cutoff hour—generally, noon for ATM deposits and 2:00 p.m. for deposits made in person. Add one business day for checks you deposit after the cutoff. The general schedule:

1. One business day for federal, state, and local government checks, electronic payments (like direct deposit of a paycheck or Social Security check), postal money orders, cash, personal checks drawn on the same bank, cashier’s checks, and certified checks. To get one-day access, certain checks have to be deposited in person or sometimes on special deposit slips. Ask about this if your timing is critical.

2. Two business days for local checks.

3. Five business days for out-of-town checks.

4. For cash or checks deposited on a business day (not Saturday) in the bank’s own ATM: one business day for U.S. Treasury checks; two business days for cash, local checks, cashier’s checks, and state and local government checks; and five business days for out-of-town checks.

5. For cash or checks deposited in an ATM not owned or operated by your bank: five business days.

6. On checks you mail to the bank: one business day after receipt by the bank for U.S. Treasury checks; two days for cashier’s checks, postal money orders, and local checks including the checks of your own state and local governments; five days for out-of-town checks.

Is a bank ever allowed to hold checks longer than usual? Absolutely. It needs at least some weapons against the risk of fraud. Expect a delay in drawing against deposited checks if:

1. You’re a brand-new customer. The bank gets 30 days to take your measure, during which time you might have to wait longer than usual for checks to clear. But on the next business day, even new customers can draw on the first $5,000 of funds from a government, cashier’s, or travelers check, or from deposits made electronically. So if you move, transfer your bank account by wire. If you bank entirely online, you won’t have to transfer your account at all.

2. You repeatedly overdraw your checking account or are redepositing a check that bounced. In this case, a local check can be held for 7 business days and an out-of-town check for 11 business days.

3. You deposit more than $5,000 in checks in a single day. Part of your money will be released on the normal schedule; part can be held up to 6 business days longer.

4. The bank has “reasonable cause” to think that something is fishy. This covers such things as suspicion of fraud, suspicion that the account holder is going bankrupt, or concern that the check is too old to cash.

These rules all apply to withdrawals by check or to cash withdrawals through a human teller. Limits are also allowed on cash withdrawals through an ATM. Limits on cash withdrawals are always allowed for security reasons, through tellers as well as through ATMs.

It’s the fee known in bank jargon as deposit item returned (DIR). You may be charged a DIR when you get a check, deposit it, and then learn that it bounced. You are blameless. You had no idea the check wouldn’t clear. Nevertheless, the bank nicks you for an average of $6, with some banks going as high as $10 (large banks charge more than small ones). If the DIR drops your account below the minimum balance, you’re charged a fee for that too.

In most cases, the checks aren’t truly bad. The writer just made a math mistake in his or her check register, forgot to enter past checks, or thought a paycheck would clear faster than it did. When the check is resubmitted, it’s usually good. Still, the innocent party pays. If you’re hit with a DIR, call your bank and ask it to cancel the charge. It sometimes will.

Faster than you think possible. If you give a check to a major retailer, it may be scanned into the banking system right from the store and debited from your account before you get home. Never count on having a day or two of “float” before your checks are cashed. Treat your checkbook as if it were a debit card.

You probably never heard of ChexSystems. But you’re on its blacklist if you ever mismanaged a bank account. Banks report people who dupe them in some way. Maybe your account was overdrawn, the bank closed it, and you never paid what you owed. Maybe you withdrew $100 through an ATM, then closed your account before the bank learned about the $100. Maybe you didn’t realize that you got $100 too much. But your intentions don’t matter. If you beat the bank out of money, it will report you to ChexSystems. When you try to open a new account somewhere else, you’ll be denied. If you pay the old bank what you owe, it’s supposed to add that fact to your file. Even so, a new bank might refuse to take you on. Black marks stay on your ChexSystems report for five years, unless the reporting bank asks that it be removed.

The Shared Check Authorization Network (SCAN) is a similar database used by retailers and other businesses that accept checks. They scan your check against the names of people who have bounced checks and not made good. The database also shows whether your bank account is still open. If you appear to be passing a bad check, the retailer won’t take it. Unpaid checks stay on the system until the retailer reports them as paid or otherwise resolved. If you don’t pay, you stay on the record for up to seven years.

If you think there’s been a mistake or you don’t know what you’ve done wrong, go to Consumer Debit Resource (www.consumerdebit.com/consumerinfo/us/en/scan/report/index.htm) for information on how to order your reports. You can print order forms to mail or fax. Or call ChexSystems at 800-428-9623 or SCAN at 800-262-7771 (have your checking account number and driver’s license number ready).

To cash checks at a branch other than your own, get a signature card.

When you endorse a check (that is, sign your name on the back), it becomes as good as money and can be cashed by anyone who finds it. To prevent that, endorse it with instructions: “Pay to the order of Amanda Smith” or “For deposit only.” When accepting an endorsed check from someone else, ask him or her to write “Pay to the order of [you],” so that if you lose it, neither of you will be out the money.

Endorse checks on the back, at the left-hand end, in the first inch and a half of space. If your signature is anywhere else, the bank may ask you to sign again. Most checks now carry a line to show where your signature goes.

Technically, a check may be good for years. But in practice, the bank might refuse any check that is more than one year old. That is, if the bank notices.

If you write a check and wish you hadn’t, call your bank and ask it to stop payment. Your account should be flagged right away, but you have to follow up with written authorization, usually by filing a stop-check form. The cost: $18 to $32. A stop payment lasts for a limited period of time but can be renewed. If the check slips through, the bank takes responsibility for it. The stop-check form should spell out the rules.

You can arrange for regular, automatic transfers from your checking to your savings account. Interest earned on your certificates of deposit can be deposited into either account.

If someone forges your signature on a check and the bank cashes it, you are entitled to 100 percent reimbursement. It doesn’t matter that you failed to report that your checkbook was stolen (although you should have). It doesn’t matter that you kept your checks with your credit cards, which carry your signature. In most cases, it is the bank’s absolute responsibility to guard against forgery. Some banks blame you and refuse to pay, in which case you should write directly to the bank’s president and to its state or federal regulator.

You have a responsibility too. If you don’t report a forgery within 14 days after the bank mailed your statement and fraudulent checks continue to be cashed by the same person, the later losses are all yours.

Use a certified check when the person you’re paying wants a guarantee that the check will be good. The bank certifies that the check will be paid by withdrawing the money from your account when the check is issued. A cashier’s check can be used by people with no checking account. You give the money to the bank, and it issues a check on its own account. Banks, money order companies, and the post office also issue money orders, payable to specific people. Keep all receipts. They’re your only proof of payment. File them as if they were canceled checks.

If you have a checking or savings account that you haven’t touched for a while, check into its status. Some banks stop paying interest on quiescent accounts. Some even start charging fees. You can usually return to claim an old account, but you won’t receive any interest for the years it lay dormant or get back the fees that you were charged.

If your bank accounts lie untouched for three to seven years (and sometimes longer, depending on your state), the money will be turned over to the state treasury (page 28). Ditto for property in safe-deposit boxes, certificates of deposit, even property held by the bank in trust. The bank, saving and loan (S&L), or credit union first has to try to reach you by writing to your last known address and putting a notice in a local newspaper. The state may have to advertise too. If you don’t show up, the money goes. You (or your heirs) can get it back by going to the state with proof of ownership. But only a few states pay interest on the accounts they’ve held.

If you owe the bank money and haven’t paid, it can generally dip into your other accounts—savings; checking; sometimes even a trust account, depending on the trust document—to satisfy the debt. Some states put modest limits on which accounts can be seized for what. Federal law prevents banks from taking money to satisfy a disputed credit card bill. But otherwise you are at risk for your own unpaid loans and any loans that you cosigned.

Good news: you don’t have to. The Rockies won’t crumble, Gibraltar won’t tumble, if you take the bank’s word that your balance is right. It’s important that your written check register comes close enough, so you don’t overdraw or fall below the minimum balance the bank requires. But what’s a $1.26 discrepancy among friends? If you’re allergic to arithmetic, bank online, where you always have an automatic running tally of your balance. If you’re still in the pencil-and-paper age, here’s the minimum you can get away with:

Enter every deposit and withdrawal on your check register as you go along, not forgetting your dealings with ATMs, direct deposits such as paychecks, bills paid automatically through electronic transfers, and money withdrawn when you paid for something with a debit card. (For more on debit cards, see page 276.)

Enter every deposit and withdrawal on your check register as you go along, not forgetting your dealings with ATMs, direct deposits such as paychecks, bills paid automatically through electronic transfers, and money withdrawn when you paid for something with a debit card. (For more on debit cards, see page 276.)

When the statement comes in, check every deposit and withdrawal against your check register to be sure there aren’t any errors or alterations. If you wait a year or more to report a mistake, the bank might not make good.

When the statement comes in, check every deposit and withdrawal against your check register to be sure there aren’t any errors or alterations. If you wait a year or more to report a mistake, the bank might not make good.

Note each check that was cashed.

Note each check that was cashed.

If you have an interest-paying checking account, add the interest the bank paid that month to your checkbook balance. Then subtract all the fees. (These items show on your monthly statement.)

If you have an interest-paying checking account, add the interest the bank paid that month to your checkbook balance. Then subtract all the fees. (These items show on your monthly statement.)

Assuming that nothing feels wildly out of line, it’s okay to leave it at that—even if your bottom line is a little different from the total the bank reports. I don’t always trust a bank to enter checks correctly, but I do trust its addition. (My own addition isn’t so hot.)

Every six months or so, purge your math errors. Take the current balance as reported by your bank, add all new deposits, subtract all uncashed checks, enter the result as the new balance in your checkbook, and start over. If the error seems large, take your checkbook to the bank and ask for help.

Mind you, I don’t recommend that you leave your checkbook a mess. But getting it in perfect balance isn’t the Oscar of good financial planning.

The ATM is McBanking at its easiest. You insert a card and punch a few buttons. Instantly, you’re in touch with your bank account to confirm your checking account balance, withdraw or deposit funds, or, at some machines, switch money from one account to another. Banks hook up their ATMs to national and international networks, so funds are available when you’re out of town or traveling abroad. I’ve given up traveler’s checks; I travel with only cash and an ATM card.

Most banks don’t charge you for using their own ATMs. If you reach your account through another bank’s ATM, that bank will claim a fee—usually in the $1.50 range. The ATMs in retail stores may cost $2 or $2.50. Abroad, you’ll be charged up to 3 percent. Deposits are usually free (but not always). You’ll probably be charged even if all you want is to check the balance in your account or get a cash advance on a credit card.

If the Big Attraction of ATMs is Convenience, the Big Risk is Crime. When you slip your card into an outdoor ATM, you’re a sitting duck for a cruising crook. He knows that you’ve just picked up some cash. If he has the time, he might force you at knifepoint to tap your account for even more. Then he might steal your car and drive away.

ATM crime is growing, although no one knows by exactly how much. Banks don’t like to report it for fear of scaring you away. Also, full disclosure of the risks of using ATMs might give victimized customers stronger grounds for suing the banks to recover their losses. So the bankers keep mum.

Under the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, your bank has to reimburse you for all but $50 of an unauthorized withdrawal, provided that you report the loss immediately. So you’re covered if a thief swipes your card and drains your account. You are also covered if you’re persuaded by a gun in your back to empty out your account. Some institutions have tried to avoid paying customers in this situation, but the law says that you’re owed.

It is not at all clear, however, that the bank has any liability for your losses if you’re knocked on the head as you’re leaving the machine. Customers have sued their banks, but most of the cases are settled out of court. In at least one case, a bank argued successfully that the customer was himself negligent for using a poorly lighted ATM at night. Here’s how to play it safe with an ATM:

Don’t use ATMs at night, even if they are located on bank property. A survey by the Bank Administration Institute discovered that most ATM crimes take place in the evening between seven and midnight, on bank premises.

Don’t use ATMs at night, even if they are located on bank property. A survey by the Bank Administration Institute discovered that most ATM crimes take place in the evening between seven and midnight, on bank premises.

Don’t use ATMs in isolated areas at any time.

Don’t use ATMs in isolated areas at any time.

Don’t use ATMs that are badly lit or readily accessible to a quick-hit thief in an automobile.

Don’t use ATMs that are badly lit or readily accessible to a quick-hit thief in an automobile.

Don’t be the only person at an ATM.

Don’t be the only person at an ATM.

Don’t use ATMs that are hidden by shrubbery.

Don’t use ATMs that are hidden by shrubbery.

Don’t use a drive-up ATM without first locking your car doors.

Don’t use a drive-up ATM without first locking your car doors.

Don’t use ATMs that lack a permanent surveillance camera that could identify an assailant. (During a Florida lawsuit, it was discovered that although a sign at an ATM said the machine was under surveillance, no camera existed.)

Don’t use ATMs that lack a permanent surveillance camera that could identify an assailant. (During a Florida lawsuit, it was discovered that although a sign at an ATM said the machine was under surveillance, no camera existed.)

Don’t write your personal identification number (PIN) on your ATM card. The PIN tells the bank machine that you’re really you. If your card is lost, that number is an open door into your account.

Don’t write your personal identification number (PIN) on your ATM card. The PIN tells the bank machine that you’re really you. If your card is lost, that number is an open door into your account.

Don’t give your PIN to a stranger. If the stranger claims to be a cop or banker, he’s lying. No one but a crook would ask.

Don’t give your PIN to a stranger. If the stranger claims to be a cop or banker, he’s lying. No one but a crook would ask.

What about relatives and friends? If you give them your PIN so they can use your account and they take more money than they should, you have to swallow it. The bank won’t pay. Ditto if your daughter finds your PIN and writes herself electronic checks. Change your PIN if you want to rescind someone’s access to your account.

When you have to get money to someone in a hurry, a check might serve if it’s delivered fast. Use a commercial overnight delivery service or the post office’s Express Mail. If the recipient has nowhere to cash the check or doesn’t have time to wait for the check to clear, use one of the following quick-delivery systems:

1. An ATM card. If the recipient has a card, you can put money into his or her U.S. bank account. It can be withdrawn at a cash machine, here or abroad. Abroad, you’ll get the wholesale rate on your currency exchange.

2. Postal money orders sent by Express Mail. You can count on rapid delivery only within the United States. International money orders are governed by country-to-country agreements and may take four to six weeks to arrive.

3. Western Union. Call 800-325-6000 or go online at www.westernunion.com. By phone, you can charge up to $10,000 on your Visa, MasterCard, Discover Card, or debit card. Online, the limit is $999.99 to $2,999.99, with Visa, MasterCard, or your debit card. Or take cash (sometimes a cashier’s check is okay) to a local Western Union agent. Some agents, and the 800 service, are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Cash can be transferred within the United States, to Puerto Rico, and to more than 190 foreign countries in 15 minutes or less. Funds wired elsewhere usually take at least 2 business days because delivery goes through local banks. The recipient can pick up the money at any Western Union agency. For the address of the closest one, ask the local agent or the 800 operator.

4. MoneyGram. It will transfer cash to more than 170 countries, for pickup within 10 minutes. To find a nearby location, go to www.moneygram.com or call 800-MONEYGRAM (for Spanish, call 800-955-7777). You can also send money through an online account. The limit is $500, charged to your Visa or MasterCard, or $899.99 if you’re debiting your bank account.

5. The U.S. State Department. It’s the agency of choice if your son was robbed in Bangladesh. In an emergency it will send cash within 24 hours to any American embassy or consulate for a fee of $30 per check. All you have to do is get the money to the State Department, using Western Union, bank wire, overnight mail, or regular mail. For details, call Overseas Citizens Services at 888-407-4747.

6. Your bank, for big-money transfers within the United States. It can wire money to another bank for pickup the same day or one day later. But mistrust banks for international transfers. Unless the foreign bank pays a lot of attention, a transfer that ought to take a day can take a month.

Ask what identification the recipient will need in order to pick up the money. Usually two proofs are required, such as a passport and a driver’s license. Sometimes he or she will also need a code word or authorization number that you furnish.

Slowly, banks are looking into quick-money transfers for smaller amounts. Ask if you can get a check delivered overnight. If you’re sending money to another of the bank’s customers, ask if you can make an instant transfer from your account.

To Get Extra Money When You’re Out of Town. If you run short of cash or traveler’s checks or your wallet is stolen, there are several ways to rescue yourself:

1. Get someone at home to send you money, using one of the techniques just described.

2. If you know your Visa or MasterCard number, call Western Union at 800-325-6000, charge your card for up to $2,000, and send money to yourself.

3. If at least one of your cards wasn’t stolen (just in case, travelers with two cards should keep them in two different places), you have some choices. Your ATM card will plug into one of the national (and international) ATM networks. You can generally withdraw $200 to $600 a day from your account at home. You might also be able to get a cash advance against your credit card or overdraft checking. Transaction fee: usually $20 to $30. Many ATM webs have toll-free numbers that you can call to find cash machines wherever you go.

The leading credit cards, such as Visa, MasterCard, and the various cards from American Express (Blue, SkyPoints, and so on), offer loans against their lines of credit through ATMs or banks—domestic and foreign—affiliated with the card’s sponsor. You pay the cash-advance interest rate plus fees. Amex’s charge cards work through the company’s Express Cash service. If you have a green card, you can use an ATM to tap your bank account for up to $1,000 a week. Gold card holders can get up to $2,500 a week; platinums, up to $10,000 a month. Fee: 3 percent, with a $5 minimum. (The ATM owner will probably charge you something too.)

4. Take some checks when you travel. Many stores, hotels, and restaurants accept personal checks from tourists. American Express holders can cash personal checks (up to certain limits) at any Amex office, as well as at some hotels and airlines.

For savings, choose an online bank. They’re paying top interest rates on accounts opened with as little as $1 and charging no monthly fees. You reach your savings by debit card or by transferring money to a checking account, either at the online bank or at your current account at a traditional bank. The banks vary the rate, depending on market conditions. At this writing, the high-paying banks with no fees and no minimum-deposit requirements include EmigrantDirect, HSBC Direct, and ING Direct (see p. 46). Some traditional banks such as Citibank may also offer online savings at high rates. Online banks also offer high-rate certificates of deposit.

At most traditional banks, however, your options aren’t as good. The savings accounts are generally of two types:

Regular Savings, for Small Accounts. You need minimum deposits in the $200 to $500 range. Interest rates are low. You’re charged fees for falling below the minimum, and they may exceed the interest you earn. Some charge no fees as long as your account stays above the minimum, but you’ll earn a barely visible interest rate. There might be free accounts for kids.

Money Market Deposit Accounts. They pay higher rates on minimum deposits of around $1,500 and up. Rates rise if you keep more money there, but they’re still not competitive with the online accounts. You get unlimited deposits and withdrawals, although each withdrawal might have to exceed a certain minimum amount. These accounts can also be used to pay a few bills. You’re allowed up to six preauthorized transactions a month, three of which can be checks to third parties (the others can be automatic bill paying or checks written to yourself). You’ll be charged monthly fees if your deposit falls below the minimum. Your account is FDIC insured.

Savers tend to use money market deposit accounts because they’re there. But a smarter buy is often a money market mutual fund (page 220). Mutual funds pay around 0.5 percentage point more than bank accounts when interest rates are low and as much as 3 percentage points more when rates are high. At this writing, they’re competitive with the savings accounts online. One risk: mutual funds are not federally insured. (For more on money-fund risk, see page 220.)

Certificates of Deposit. You commit your money for anywhere from 6 months to 10 years. Some institutions set fixed terms, such as 1 or 2 years; others let you pick the exact number of days, weeks, or months you want. Normally, the longer the term, the higher the interest rate. For CDs too, online accounts tend to beat those at traditional banks.

You normally pay a penalty (of 1 to 6 months’ interest, and sometimes more) for withdrawing funds before the term is up. But don’t let that scare you out of choosing a CD. If you’re forced to break it before maturity and pay the penalty, so be it. That won’t be the first bit of money you’ve frittered away. The chances are, however, that you’ll keep your CD for the full term and earn more interest than you’d have gotten from a regular savings account.

High-Yield CDs. Some traditional banks offer higher yields than you’ll find even at Internet banks. You can locate them through Bankrate.com (look for the “100 Highest Yields” page). Typically, they require minimum deposits of $1,000 and up. There’s no need to worry about the safety of high-yielding institutions. As long as they’re covered by the FDIC, you won’t lose any money.

To make a long-distance deposit in a high-rate bank or S&L, call the institution that interests you and ask for the deposit forms. Or get the forms online. You can mail the bank a check or transfer money directly from your present bank.

Broker-Sold CDs. The major stockbrokerage houses sell CDs, not at top rates but at rates above average. The bank pays the sales commission, not you. The minimum investment is generally $1,000. One hitch: a broker-sold CD can’t be cashed in before maturity, which could be as long as 20 years. If you need the money early, the broker will put it up for sale and try to get you a reasonable price.

Which Type of Savings to Choose? Pick money market or regular savings account for cash you might need at any moment. Pick a CD for cash you have to keep safe but won’t need immediately, such as your daughter’s tuition for next year or money you’re saving for a new house.

Yield Shoppers Beware: Advertised high yields are sometimes good for only 30 or 60 days, after which they drop. For a reality check, always compare the annual percentage yield (APY) with those of competing CDs.

By federal law, banking institutions all have to figure their interest rate yields in a standard way. That’s disclosed in an annual percentage yield. Always use APY to compare two interest-paying bank accounts. No matter what else the advertisement may say or how often your deposit compounds, the bank with the higher APY is paying more on your checking account or savings deposit.

You can earn the highest possible interest on CDs, without surrendering easy access to your money, by using a simple strategy called “laddering.” Here’s how it works, assuming an initial pot of savings of $6,000:

You start out by splitting that money among bank deposits of varying maturities: $1,000 into a money market account, for cash on hand; then $1,000 each into 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year CDs (or different maturities, depending on what you find). Normally, the longer the maturity, the higher the interest rate.

One year later, your first CD will mature, paying $1,000 plus interest. If you don’t need the cash, reinvest it in a new 5-year CD, which pays a higher interest rate. You can risk putting money away that long because in another year your next CD will mature—once again, giving you cash on hand. If you still don’t need the money, it too goes into a new 5-year CD.

If you do this each time a CD matures, all your money will soon be earning 5-year interest rates. Yet a $1,000 certificate will come due every 12 months, providing ready cash if you need it. Result: you will earn much more on your money without having to tie it all up for 5 years at a throw. You could stretch out this ladder by using 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-, and 9-year CDs.

Some mutual fund companies offer a fund that ladders CDs for you.

Hungry bankers and brokers respond to every fresh scent on the wind. Show them a new market, a new worry, a change in the economic outlook, and they will design a certificate of deposit to match. Not all banks offer exotic CDs. Those that do may call them by different names than I have used. But if these ideas interest you, watch for them in the newspaper, TV, and online ads, in bank windows, or in communications from your broker. The better the deal, the larger the minimum deposit the institution may want. Always compare the annual percentage yield with those being offered by standard CDs of the same term. Sometimes the designer CDs pay less. Also, check the maturity date. Some investments that look like 1-year CDs actually lock up your money for 15 or 20 years.

Liquid CD: if you think you might need some of the money before maturity. You’re charged no penalty for early withdrawal of some or all of your funds.

Bump-Up CD: if you expect interest rates to rise. If that indeed happens, the bank will—at your direction—raise the rate you are earning on your CD once or twice during its term.

Step-Up CD: also for people who expect higher rates. This CD pays less now but guarantees higher rates in the future. It’s especially important to compare a step-up’s APY with those for fixed-rate CDs of the same term. Step-ups offer dazzlingly high yields in, say, their final 3 months. But on average, they may pay less than a plain-vanilla CD.

Variable-Rate CD: again, for people who expect higher rates. Your interest rate rises and falls with the general level of rates. Buy it only if there’s a guaranteed floor below which the interest rate cannot go. The rates on some variable CDs rise and fall on a preset schedule, over time.

Market-Linked CD: This is a complex investment product, not a bank product. Beware its many risks.

Bitter-End CD: if you know you can last for the full term. You get a bonus for keeping your money in the CD for a full 5 years.

Zero-Coupon CD: if you want to make a gift of money look extra good. You put down a small sum now, at a guaranteed interest rate. It will grow to equal the CD’s larger face value in a given number of years. Each year’s increase in value is taxable, even though you get no cash payout. So zeros are best kept in a tax-deferred retirement account. Always ask for the annual percentage yield and compare it with those of regular CDs of the same maturity. Some institutions clip you a little on their zeros.

Jumbo CD: if you (or a group of investors) have more than $100,000 or $250,000. Banks pay higher interest rates on large amounts of money. But choose a safe institution. If your bank fails and the government can’t find a buyer for it, your deposits over $250,000 may not be fully reimbursed.

Tax-Deferral CD: if you’re chiefly interested in deferring your tax. This 12-month CD is bought at a discount in the current calendar year, to mature next year. No interest is paid until the CD matures, which puts all of your income into the next tax year.

Callable CD: Beware this broker-sold CD. It pays a slightly higher interest rate than a regular CD of the same term, but if interest rates go down the bank can redeem it, leaving you to buy a new CD at a lower rate. If rates rise, the bank will not redeem the CD. The broker will sell it for you if you want to cash in, but probably for less than you originally invested. These CDs may not mature for 15 or 20 years. The broker might offer you a “1-year noncallable,” but that’s not a 1-year CD. It’s a 10- or 15-year CD with one year of call protection, meaning only that the issuer can’t take it away from you in the first year.

Are you looking for higher interest rates than CDs will pay? Some banks sell an instrument called a subordinated debt note, lobby note, retail debenture, or similar term. When you buy it, you are lending money to the institution, unsecured. Lobby notes don’t carry federal deposit insurance. If the institution goes broke, your investment will probably be worthless.

Banks that peddle these notes may not be in the greatest financial shape. Not only are you shafted if the institution fails, you are also shafted if it succeeds. The fine print in a lobby note usually allows the bank to redeem it before the full term is up. So you might lose the high interest income you expected.

Other financial institutions also offer high-rate notes—for example, the Demand Notes sold by GMAC Financial Services or the Interest Advantage notes from Ford Motor Credit Company. Like bank notes, they’re backed only by the company itself. You gotta have faith.

When you open a CD, ask the bank what happens when the certificate matures. What instructions does it need regarding what should be done with the CD’s proceeds, and how soon does it need them? Can you give instructions now? All this information will be in your CD contract but it’s important that you understand it exactly.

Each institution handles things a little differently. Normally, there’s a short grace period after maturity—maybe 7 to 10 days but sometimes as little as 1 day—during which the bank waits to hear from you. Do you want the money invested in another CD or moved to another account? Interest may or may not be paid while you’re making up your mind. If the grace period expires and you haven’t told the bank what to do, your money will probably be reinvested in another CD of the same term. If you then decide that you want the cash, you might be able to break the CD without penalty. On the other hand, you might not.

Banking institutions have to notify you shortly before your CD matures. But keep track of the payment date yourself, just in case there’s a slipup. Don’t leave your decision to the last minute. The bank might want written instructions, and you’ll have to allow enough time for them to arrive.

Banks also sell mutual funds and tax-deferred annuities. They note when your CDs are coming due and call you with a sales pitch. You might visit with someone you think is a banker and never learn that he or she is actually a broker angling to sell you a product and earn a commission. Your friendly teller might have to refer you to these brokers in order to keep his or her job. The tellers earn commissions or bonuses too.

At some banks you will get a full and fair explanation of annuities and mutual funds. But don’t count on it. All too often, the operation reeks of deceptive sales tactics. How bad are they? American Banker, an industry trade paper, once sent reporters posing as mutual fund customers into ten banks. Reps at eight of those banks “forgot” to mention that mutual funds aren’t federally insured; only a few of them disclosed fees; most downplayed the investment risk; some illegally forecast specific (and double-digit) gains; and one even suggested that mutual funds were like CDs but with higher yields.

Similar surveys using “mystery shoppers” keep turning up similar results. Some customers don’t realize they’ve bought mutual funds or annuities, don’t understand the risks, and find out too late that there’s a stiff penalty for withdrawing money before several years have passed. In one case I’m familiar with, a 92-year-old man was sold an annuity with withdrawal fees lasting until he was 99. He thought he was buying a high-rate CD.

According to federal guidelines, banks are supposed to:

Industry guidelines add that all sales commissions, surrender charges, and other fees should be fully disclosed.

Should you invest with banks? To help you decide, see chapter 22 (mutual funds) and page 1072 (fixed-rate tax-deferred annuities).

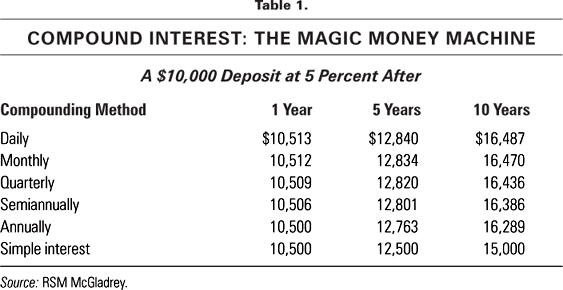

1. Ask: How often does interest compound? Compounding means that the bank adds the interest you earn to your account and then pays interest on the combined interest and principal. The more often your interest is compounded, the more money you make. Daily or continuous compounding (they’re just about the same) yields the most, followed by quarterly compounding, then semiannual, then annual. With “simple” interest, there is no compounding at all. What difference does it make? Plenty. At 6 percent interest, compounded daily, your savings are worth 14 percent more after 10 years than if you had earned only simple interest. Compounding is included in the annual percentage yield. At equal rates of interest, an account that compounds daily or continuously will have a higher APY than one that compounds any other way.

2. Ask: How often is interest credited to your account? Most banks that compound interest daily do not actually give you the money until the end of the month or the end of the quarter. So then ask: What happens to that last bit of interest if I close my account before the end of the period? Normally, you will lose it even though the bank claims that it’s paying you right to the day of withdrawal.

3. Ask: What is the annual percentage yield on your savings? This yield takes all kinds of mathematical quirks into consideration, not only interest rate and frequency of compounding but also such technical details as how many days the bank counts as a year. (Some banks use 366 days, others use 365, still others 360. For reasons only Computerman would believe, 360 yields more interest.) The higher the APY, the better the deal.

4. Ask: What is the periodic payment rate? That’s the rate the bank applies during each compounding period when figuring how much interest you have earned. Knowing it, you can check the bank’s calculations to see if it paid you properly (that is, if you’re into decimals). Mistakes are not uncommon. A good bank will give you its periodic payment rate and show you how to use it.

How many times have you cashed a check in a hurry, then walked away without counting the money? Maybe you think the teller is always right. Maybe you are intimidated by the line of grumpy people behind you. But if you count the money at the bank door and find that you’re $20 short, you might be stuck. Tellers aren’t allowed to hand over extra money on a customer’s say-so. After all, you could have slipped the missing $20 into your pocket before you went back to the teller’s window.

Rule 1. Count your money before leaving the window. If you discover an error later, give your name, address, and account number to the manager. If the teller winds up the day with the right amount of extra cash, you’ll be reimbursed.

Tellers sometimes err when crediting deposits—for example, entering $100 when you actually put in $1,000.

Rule 2. Double-check every transaction for accuracy before leaving the window. If you mail deposits, check your paper or online statement. What if the teller credits $1,000 to your account when you gave him or her only $100? Don’t spend the money. The mistake will be found, and in banking, there’s no finders keepers.

ATMs goof, just as people do. They shortchange the occasional customer, giving you $80 when you asked for $100. Sometimes they accept cash and checks without crediting them to your account.

Rule 3. Never deposit cash in an ATM. It’s impossible to prove how much you put into the envelope, so losses are sometimes hard to recover. Checks are easier to find or replace.

Rule 4. Report mistakes right away. Some banks install telephones next to their ATMs for that purpose, although they may be answered only during banking hours. When you call, leave your name, address, account number, the amount of the loss, and the location of the ATM; then put the same information into a letter. You will have to wait until the accounts are balanced, but if the machine is over by the sum that you reported, you will get your money. At the bank’s own ATM machines, the error might be fixed at the end of the day. But it will take an extra day or two (and sometimes weeks) if you used an ATM at another bank.

It always astonishes me to see the trash baskets near ATMs overflowing with deposit receipts. If the deposit is entered wrong, would those customers know it? (I don’t remember the exact amounts of the various checks I get.) Withdrawal slips are also dumped—by people who aren’t balancing their checkbooks, I guess. But what if there’s an error?

Rule 5. Keep all deposit and withdrawal slips until your bank statement comes in to be sure the transactions were entered correctly.

Your bank might automatically renew your CD when it expires even though you told it not to.

Rule 6. Keep a copy of the instructions you gave when you opened the CD and mark the due date on your calendar. If an error is made, hustle to correct it. Too long a wait may cost you your chance to get your money out.

If your bank fails, it will pay right away—usually the next business day.

Don’t believe investment advisers who try to steer you away from banks with the claim that, if the bank closes, you’ll have to wait 99 years for your money. And don’t waste your time searching through subclauses, thinking you’ll find a loophole in your coverage. The federal government will restore 100 percent of your insured account, and fast. This applies to all insured institutions—banks, credit unions, and savings and loans.

During the 2008 credit crunch, Congress raised the deposit insurance ceiling to $250,000 from $100,000, which covers almost everyone. At this writing, it’s scheduled to return to $100,000 in 2014, but who knows? Maybe Congress will decide to keep the higher amount.

You can find the current insurance limit at www.fdic.gov/deposit/index.html. Your deposits are entirely safe up to that amount—and more, depending on how the accounts are held. Safe in a failing bank. Safe in a bank that pays cockeyed interest rates. Safe even with a crook or incompetent at the institution’s helm. So don’t worry, be happy, and collect the highest interest rates you can find.

To estimate how much insurance you have on multiple accounts in the same institution, use the FDIC’s easy calculator at www2.fdic.gov/edie/index.html. You get the full amount of coverage on each of the following accounts or groups of accounts:

1. All the accounts in your name alone, added together, including any accounts in the name of a business you own as sole proprietor.

2. Each account that you hold jointly with different people. The FDIC splits joint money evenly among the account holders. Then it adds up each holder’s money to see how much is insured. As an example, say that the ceiling is $250,000 and that you own three joint accounts—one with your spouse for $350,000, and an $80,000 account with each of your two adult children. For the first account, the FDIC assigns $175,000 of coverage to you and $175,000 to your spouse. You’re also assigned half ($40,000) of each of the two $80,000 accounts, leaving each child the other half. Your spouse’s and children’s money falls under the $250,000 umbrella, so their shares would be fully insured. But your share totals $255,000. That leaves $5,000 uninsured.

The FDIC lumps together all accounts held jointly by the same people, such as a checking and savings account owned by a married couple, and gives you each the maximum coverage. When the insured ceiling is $250,000, joint accounts are covered up to $500,000.

Some couples try for double coverage by shuffling the names on the accounts—listing one as husband/wife (with the husband’s Social Security number) and the other as wife/husband (with the wife’s Social Security number). Nice try, but it doesn’t work.

You may not have joint coverage if you put a small child’s name on a checking or savings account. A child under 18 cannot legally make withdrawals, so he or she isn’t a true co-owner. If the FDIC discovers that the child is a minor, all the money in the account will be assigned to you.