Leave your $1,000 in the bank. You’re losing 15 percent a year—the 18 percent cost of the debt minus the 3 percent gain from the savings account.

Leave your $1,000 in the bank. You’re losing 15 percent a year—the 18 percent cost of the debt minus the 3 percent gain from the savings account.Patented, Painless Ways to Save and Where to Save It

The 1980s worshiped spending. The 1990s worshiped debt.

The twenty-first century belongs to the saver.

It seems like only yesterday that savers were dorks. They kept piggy banks. They drove last year’s cars. They fished in their change purses for dimes while the superstars flashed credit cards.

Today values are changing. The new object of veneration is not money on the hoof but money in the bank—and the dorks have it. The more you save, the freer you become, because time is on the saver’s side. Compound interest floats all boats.

Like most people who make their own money, I started out living paycheck to paycheck. I could cover my bills (most of the time). But I “knew” that I couldn’t afford to save, so I didn’t bother. Even had I bothered, my small $20 or so a week wouldn’t have seemed worth the effort.

Some years (and many lost $20s) later, I learned I was wrong. Anyone can put money aside, at any level of income. You just have to do it. Of all of the New Era’s new virtues—daily jogging, eating bran, going green—saving money is the simplest and the least demanding of your time and attention. Savers can lie in a hammock all day lapping ice cream and still feel good about themselves. As for the value of a tiny $20 a week, take a look at the table on page 215.

A financial plan is grounded in savings. That’s how you get enough money to pay off your debts and accumulate an investment fund.

How much should you save? The answer comes from ancient times: you tithe. It was learned generations ago—and is still true—that most people can save the first 10 percent of their incomes and hardly notice. I can’t tell you why it works, only that it does. Tithing seems to collect the money that otherwise would go up in smoke (it’s 9:00 a.m.; do you know where yesterday’s $10 is?). On a $40,000 paycheck, you can save $333 a month, $4,000 a year. On $60,000, shoot for $500 a month, $6,000 a year. On $100,000, save $833 a month, $10,000 a year.

I hear you, I hear you. You say you can’t do it. Your rent is too high, your bills are too large, your needs are too great, your credit lines are too long. None of those things is actually an impediment, but it will take you a while to see it. So start by saving only 5 percent of your income. Take that money off the top of every paycheck, and live on what’s left. What will happen to that pile of monthly bills once you start putting 5 percent aside? They will be paid! You’ll still go to the movies and put gas in your car. Your standard of living will be unchanged. Those savings pick up dollars that leak through your fingers unseen. The rest of your life goes on exactly as before.

You say you don’t believe me? Fine. Try it and prove me wrong. When you find out it works, raise your savings to 7 percent. I predict that you’ll be at 10 percent within the year.

If you’re already tithing to your future, take a moment to feel superior. What’s life without a touch of smug?

A savings account isn’t something to hang on the wall and stare at, like a Rembrandt. You’re not hoarding. You’re preparing to use your money in a different way.

Refer, please, to your spending plan (chapter 8). It says that your current goal is to pay down debt. Or have three months’ living expenses in the bank. Or $2,000 more in a college account this year. Or $5,000 for long-term investments. Or $1,000 to play the slots in Vegas, where you’ll really make some money. Tithing, or semitithing, is how you’re going to raise your stake.

Here’s how to accomplish it:

First, write down how much you’re going to save (5 or 10 percent of each paycheck).

Second, write down how long it will take to reach your goal. At $250 a month, you’ll have your extra college money in eight months. You’ll have college money and Las Vegas in 12 months. (Tip: It’s easier to save $59 a week than $250 a month. The smaller sum sounds more doable, even though it comes to the same amount in the end.)

Third, note each future $250 (or $59) payment on your calendar and check off every one you make. That may sound hokey, but it’s a strong motivational tool. Every time you turn to a new week or a new month, there’s a written reminder to keep up your resolve. Saving money is easier if you see it climb toward a specific end. It’s like polishing the car; you feel that you’ve accomplished something.

Fourth, when you’ve reached your goal, give yourself a little present. Then start the process all over again.

No, no, and again, no. Repeat after me: paying off debt is a form of saving. In fact, debt repayment is one of the most lucrative ways to save. It’s nuts to keep money in the bank at 3 percent interest while carrying credit card debt at 18 percent. You are losing 15 percent a year on that deal (the 15 percent cost of the debt minus the 3 percent earned on the bank account). Take most of your money out of the bank and reduce the debt. If you need quick cash, you can borrow against your card, but in the meantime, you’re saving yourself a mountain of interest.

Using savings to pay off debt is one of the simplest, fastest ways of setting your finances aright. It’s also a fabulous use of your money. Your return on investment equals the interest rate on the debt. When you make an extra payment on your 18 percent credit card, for example, you’re getting an 18 percent return, guaranteed. If you pay down a 24 percent debt, you’re getting a 24 percent return, guaranteed. No other investment can offer the same.

You may find it hard to accept this truth. Money in the bank is so comforting. Haven’t you read that everyone should keep three to six months’ worth of expenses in an emergency savings account? Hardly anybody does, but the books all say that’s the right thing.

Not this book—at least, not while you carry debt. You do indeed need three to six months’ worth of basic expenses on tap in case of illness, job loss, or other emergency. A year’s worth of expenses would be even better. But you can protect yourself nearly as well with 12 months’ worth of borrowing power on credit cards or a home equity line. (I say “nearly” because borrowing builds up an obligation, while taking money from savings doesn’t.)

For mathematical proof that this strategy works, assume that you have $1,000 in the bank earning 3 percent, a $1,000 credit card debt at 18 percent, and no extra fee for taking a cash advance. Here’s your position, under various scenarios:

First, assume that no emergency comes up. You might:

Leave your $1,000 in the bank. You’re losing 15 percent a year—the 18 percent cost of the debt minus the 3 percent gain from the savings account.

Leave your $1,000 in the bank. You’re losing 15 percent a year—the 18 percent cost of the debt minus the 3 percent gain from the savings account.

Use your $1,000 to pay off the debt. Instantly, you’ve earned 15 percent (the 18 percent you gained by eliminating the debt minus the 3 percent you lost by giving up the savings account).

Use your $1,000 to pay off the debt. Instantly, you’ve earned 15 percent (the 18 percent you gained by eliminating the debt minus the 3 percent you lost by giving up the savings account).

Second, assume that, after a year, a $1,000 emergency comes up. You might:

Take the $1,000 you kept in the bank. Your cost: 15 percent (the price of not having used that $1,000 to reduce your debt).

Take the $1,000 you kept in the bank. Your cost: 15 percent (the price of not having used that $1,000 to reduce your debt).

If you used the $1,000 to reduce your credit card debt, you can borrow the money back. Cash advances are expensive so you might have to pay an interest rate of 22 percent. But subtracting the 15 percent you saved by reducing debt, your net cost is just 7 percent.

If you used the $1,000 to reduce your credit card debt, you can borrow the money back. Cash advances are expensive so you might have to pay an interest rate of 22 percent. But subtracting the 15 percent you saved by reducing debt, your net cost is just 7 percent.

You’ll probably want to keep a little quick cash in the bank, but don’t try to build a larger account until your high-rate debts are paid off.

Here’s another version of the saving-versus-borrowing question: “I need a new gallimawhatsis. I have enough money in the bank to pay cash. Should I use that money or take a loan instead?” One argument favors the loan: you will be forced to repay the money, whereas no one will grump if you leave a hole in your savings account. But a better argument favors cash: taking money from savings is the cheapest way to buy. Once you’ve made the purchase, make regular payments into your savings account (just as you’d have made regular payments on the loan) to replace the money you took out. As long as you’re capable of saving money, you don’t have to worry about using your savings from time to time.

I’d vote differently if your savings cache came from an inheritance, a life insurance payoff, or a lottery ticket, and you’ve never been able to save by yourself. In that case, consider the loan. Preserve that precious windfall for college tuition or your old age. The interest you pay, unnecessarily, is the price of lacking discipline.

Savings are, by definition, safe. You can turn your back and they won’t escape. When the stock market crashes, they’re unalarmed. Every time you look, they’ve earned more interest. You’re never going to lose a dime.

Investments, by contrast, put your money at risk. Good investments yield much more than savings over the long run. But you have to put up with losses too.

Savings will not make you rich. Only canny investments do that. The role of savings is to keep you from becoming poor. They’re your security. Your base. They preserve your purchasing power. With enough savings tucked into your jeans, you can afford to take chances with the rest of your money, and with your life.

These are tricky calculations and depend on your options. My priorities look like this:

1. Invest in a tax-favored retirement account (chapter 29). If you have a 401(k) with a company match, put in as much as you need to capture the match in full. Then …

2. Pay off high-rate consumer debt. It gives you the highest guaranteed investment return you’ll ever earn. Then …

3. Build an emergency cash reserve for personal security. I call this your Cushion Fund. Cash savings don’t earn high interest rates but help ensure that you’ll always be able to pay your basic bills. Then …

4. If your kids will go to college, start college investment accounts (chapter 20). Aim to accumulate half the probable cost, planning to pay the rest out of current income and student loans. You might get a tuition discount too. Then …

5. Return to your tax-favored retirement investments. Start putting in the maximum the law allows. If you’re already at the max, invest in regular after-tax accounts.

That depends on your age and the interest rate. Here’s how to look at it:

1. If you’re young or in early middle age, it’s more important to contribute to a tax-favored 401(k), Individual Retirement Account, or other retirement plan. If you’re contributing the maximum, open a regular, taxable investment account. Over the long run, they’ll be the better investment.

2. If you’re approaching retirement, it’s important to get your mortgage paid off. If you can’t, plan on selling the house and buying something smaller for cash when your paycheck stops. The easiest way to live in retirement is in a mortgage-free home.

3. If you’re paying a punishingly high mortgage interest rate, prepay your loan as fast as you can. You need to accumulate more equity so that you can refinance into a loan with a lower rate.

… are when you’re young. At least, they’re the best years for saving money. The sooner you start, the more time your savings have to grow.

Typically, young people turn a deaf ear. “I’m too broke,” they say. “I’ll save when I’m older.” But later money won’t earn you nearly the return that early money does.

You want proof? Take a look at the startling table on page 215, prepared by the late Professor Emeritus Richard L. D. Morse of Kansas State University. It compares early savers with savers who start late.

The Early Saver deposits $1,000 a year for 15 years at 5 percent compounded daily. Then she stops. Having put in a total of $15,000, she leaves her stash alone to build.

All during that time, the Late Saver spends every dollar he earns. In the sixteenth year, he gets religion and starts saving $1,000 a year, also at 5 percent. Forty years later, he has put up a total of $40,000. But he hasn’t caught up with the Early Saver—and never will! He can go on depositing $1,000 a year until the fourth millennium. At 5 percent interest, the Early Saver (although still depositing no more money) pulls further ahead of the Late Saver every year.

If the Early Saver’s money compounds at 8 percent, thanks to a growing stock market, the gap grows even larger. It pays to start saving at any age, but young is best.

For a close estimate, use the rule of 72s. Divide 72 by the yield you expect to earn. The result is how long it will take for your money to double. At 5 percent, your money will double in roughly 14.4 years. At 8 percent, it takes 9 years.

1. Pay yourself first. That’s the oldest financial advice in the world and one of those things you can’t improve on. Take a slice of savings off the top of every paycheck before paying any of your bills. If you pay your bills first and save what’s left, you’ll always be broke because there is never anything left.

2. Bill yourself first. Keep stamped envelopes, addressed to your bank, in the same drawer as your bills. Send the bank a fixed check every month to deposit into your savings account. Or keep a “bill” for your savings account with

the bills you pay through your bank account online. “Pay” it as if it were just as pressing as keeping the mortgage current—and in fact, it is. If you’re paid irregularly, save a fixed percentage of every paycheck.

3. Get someone else to save for you (Part One). Your bank will transfer a fixed sum of money every month from your checking account into savings or a mutual fund.

4. Get someone else to save for you (Part Two). You’ll never find a better savings machine than your company’s payroll deduction plan. A fixed amount of money is taken out of every paycheck, so the cash never hits your checking account. What you don’t see, you don’t miss—and you don’t spend. The money normally goes into retirement savings accounts.

5. Do coupons turn you on? Create your own Christmas club or vacation club. Decide how much money you want 12 months from now, divide it into 12 equal payments, and make “coupons” to remind you to keep up the monthly deposits. Or make 52 coupons for weekly payments. You could call it a Down-Payment-on-a-First-Home Club or an I’ll-Send-Junior-to-College-If-It-Kills-Me Club.

6. Save all dividends and interest when you don’t need this money to live on. If you have a mutual fund, those dividends should be reinvested automatically. If you keep stocks with a stockbroker, have the payments swept into a money market fund for reinvestment.

7. Don’t spend your next raise. Put the extra money away, even if it’s just $20 a week. The more money you earn, the more of it you should set aside. Toward late middle age, you should be saving 15 to 20 percent of your income, at least.

8. Quit spending your year-end bonus in advance. Save it instead. At the very least, quit spending more than your net bonus after tax.

9. Save all gifts you get in cash, even small ones. Nothing is too small to save.

10. Pay off your mortgage faster by doubling up on principal payments every month. You’ll build equity sooner, which is a form of saving. You’ll also spend much less on interest payments.

11. Quit buying books (except, of course, for this one, which no prudent saver should be without!). Get a library card instead.

12. Refinance your credit card, auto, or other high-interest loans at a lower interest rate. You might be able to shift your credit card balances to a cheaper card. If you’re disciplined, transfer the debts to a home equity line of credit; the interest is tax deductible if you itemize deductions. Use the money you’re saving on interest payments to reduce your debts even faster.

13. Don’t trade in your car as soon as the loan or lease is paid off. Make repairs if you have to and keep it for a year or two longer. Save the money you were spending on monthly car payments.

14. Pay cash for everything by shopping with a debit card. You will spend less because it’s harder to part with cash than to put down a credit card.

15. Take $5 out of your wallet every day and put it in a coffee can. That’s $1,825 a year—a good start on funding an Individual Retirement Account.

16. Take a part-time job and save all the income.

17. Let the government withhold extra tax money from your paycheck and save the refund.

18. Pay off your credit cards, then save the money you’re no longer spending on interest charges.

19. Trim your spending by 5 percent, then trim it by another 5 percent. Best way to trim: put 5 percent of your income into savings and live on what’s left.

20. Save early and often. The sooner you put some money away, the longer it has to fatten on compound interest. Saving money young is a painless way of saving more.

1. Join the company retirement savings plan. Your basic contribution escapes current taxes and will accumulate tax deferred. What’s more, these plans often give away money free. The company matches your contribution—say, $1 for every $2 you put up. That’s a 50 percent return on investment, instantly and at no risk. There’s no better deal in the entire U.S. of A. You may also be able to add a nondeductible contribution that can accumulate tax deferred.

2. Join your company’s stock purchase plan. You run the risk that the stock will fall. But over long periods, your investment should do better than a savings account. (One warning: Don’t let more than 5 percent of your net worth accumulate there. It’s risky to bet your future principally on one stock. From time to time, sell some of the stock and diversify into other investments.)

3. Sign up for an Individual Retirement Account. Make monthly payments so you won’t have to scramble for money when the deadline for contributions looms. For more on IRAs, see page 1047.

4. Don’t spend the lump sum distribution you may get from your retirement plan when you leave the company, even if it’s small. You generally have three investment choices: leave it in your ex-employer’s plan, roll it into an Individual Retirement Account, or roll it into your new employer’s retirement plan. If you spend it, you’ll lose the value of your early saving years, and pay taxes and penalties besides.

5. If it takes a contribution to join your company’s pension plan, make it—even if you’re young. If you leave early, you’ll get your money back plus everything your money earned. You’ll also get some or all of your company’s contribution, depending on how fast it vests.

6. Start a tax-deferred Simplified Employee Pension or individual 401(k) if you’re self-employed or earn self-employment money by moonlighting (page 1043).

7. Consider a tax-deferred annuity, but only if you’ll hold the investment for at least 15 or 20 years (page 1071). If you hold for a shorter period, the expenses and eventual taxes will add up to more than the taxes you originally saved.

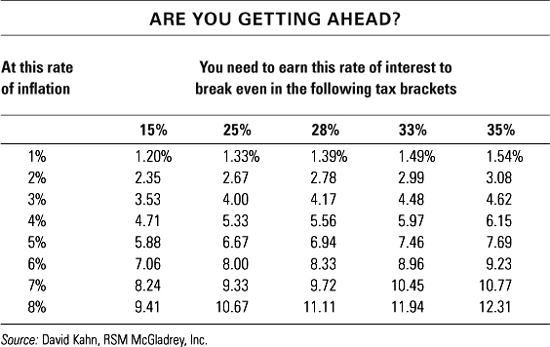

Say that inflation is running at around 3 percent. And say that you’re earning 5 percent in a five-year certificate of deposit. What’s the effective return on your money after state and federal taxes? Probably pretty close to zero—either just above it or just below, depending on your tax bracket. You may have preserved your purchasing power, but you haven’t increased it, or not by much.

I’m not knocking a break-even result. The basic job of a bond or a bank account is to keep you from falling behind. But you won’t achieve even this much protection unless you avoid low-rate deposits.

The table below gives you some guidelines. Find the current inflation rate at the left, then look across to the column showing your federal income tax bracket. Take the interest rate shown and raise it a little to compensate for state and local taxes. That’s the minimum rate that your money has to earn to keep the value of your savings from eroding.

Don’t automatically think “bank.” That’s only one of many choices. To find the right place to keep your savings safe, start with what you want from your money and work back. You need: (1) at least the break-even yield that you’ve just found and (2) access to the money when you need it but not a day sooner. Funds you

won’t want until next year can be invested differently from—and more profitably than—funds you’re going to use next week.

(I mean right now. Or a week from Friday. Within three months, at the very most.)

Hold this part of your cash cache to a minimum because ready money earns less interest than money invested for longer terms. I’d include only:

1. Funds that you know will be spent very soon, such as a down payment on a car you’ll buy this month or an ongoing renovation of your home.

2. Your permanent floating emergency fund. Don’t let this fund get too large. Keeping $10,000 in a passbook account—just in case the house should burn, the world explode, or your hair drop out—is dumb. Into the dailiness of life, costly emergencies rarely fall. If one does, you can always retrieve your money from wherever you stashed it. A quick-cash fund of two months’ basic expenses should be plenty. Savings do better when stored at higher rates of return or used to reduce debt.

3. Money waiting to be invested in stocks, bonds, or real estate.

Money Market Deposit Accounts at Banks Online. There’s no better place. Online MMDA accounts are handy, they’re government insured, and they pay higher interest rates than you’d get from traditional MMDA accounts in the very same banks. There’s no minimum deposit and no annual fee.

Money Market Deposit Accounts at Regular Banks. You earn a floating interest rate that is loosely tied to the general level of market rates. (And I mean loosely. When other interest rates go up, banks are slow to raise the rate on money market accounts. But they drop rates enthusiastically when other interest rates go down.) You can take out money whenever you want, although only six transactions a month can be with third parties and only three of those by check. Minimum balances fall in the range of $500 to $2,500. You’ll pay a penalty if your account drops below the minimum. (You may find no minimum at a few banks but probably a higher fee.)

The downside? The low interest rate. It rarely meets the break-even test. Your savings may lose value after counting inflation and taxes. If the bank charges fees, you’ll lose even more. The only hope of maintaining your money’s purchasing power is to search out an institution that pays high interest rates on money market deposits. Do it by checking “100 Highest Yields” at Bankrate.com (www.bankrate.com) or, BankingMyWay.com (www.bankingmyway.com). During the credit crunch of 2008–2009, bank money market accounts often paid higher rates than their nearest competitors, money market mutual funds.

Passbook Accounts. These pay even less than money market accounts. Skip them unless you’re below the minimum for a money market account and want to stay with a traditional bank.

Money Market Mutual Funds. Money funds offer a somewhat better chance of breaking even. In normal times, the average fund pays around 0.5 percentage point more than the average bank money market account when interest rates are low and as much as 3 percentage points more when rates are high. During the credit crunch, however, banks often paid more.

Like any other mutual fund, a money fund is a basket of various types of securities—in this case, low-risk investments that earn short-term interest rates. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) limits taxable money funds largely to U.S. Treasury securities, insured bank certificates of deposit, and top-grade commercial paper (short-term loans to creditworthy corporations). Tax-exempt money market funds, for people in higher tax brackets, invest in the short-term securities of states and municipalities, and local authorities that maintain sewers, water, and so on. All these investments usually mature within a brief time—a day, a week, three months, six months.

In theory, money market mutual funds are worth $1 a share, all the time. They don’t rise in value in good markets or fall in bad ones. They generally credit you with dividends daily (and pay them monthly), passing along whatever the fund is currently earning. Your minimum investment: $2,500 or $3,000, depending on the fund. Some require $5,000 or more. You can write an unlimited number of checks on the fund, generally for a minimum of $250 or $500. A few process $100 checks. You pay no penalties for low deposits, although many funds will cash out your shares if your balance falls below a certain minimum, such as $500 or so.

But … money funds, including the money funds sold by banks, don’t carry federal deposit insurance. So although the funds are extremely safe, they’re not perfectly safe. In 2008, the giant Reserve Primary Fund got stuck with worthless commercial paper from Lehman Brothers, an investment bank that suddenly failed. Share values at Primary dropped to 97 cents a share—a shock called “breaking the buck.” Investors fled similar money funds and didn’t return until the U.S. Treasury stepped in to offer temporary insurance.

Back in 1989 and 1990 some corporations defaulted on their commercial paper, posing a potential loss to a few money funds. In 1994 a sharp rise in interest rates damaged a handful of funds invested in the riskiest sort of derivatives—complex investments whose market value isn’t always clear. No one lost money. Those funds were sponsored by large financial institutions that dipped into their pockets to make investors whole. Reserve Primary wasn’t owned by a financial institution and couldn’t make good. I still think that money market funds are safe enough, but only if they’re owned by major institutions that can afford to support the $1 price.

Money funds come in various types:

The supersafe. They invest only in U.S. Treasury bills and buy no Treasury derivatives. In general, investors earn less than they would in other funds. An exception could be an investor in a high-tax state such as California, Massachusetts, or New York. Dividends paid by Treasury funds are exempt from state and local taxes. As a result, they may net you more than funds invested in taxable corporate securities, especially if the Treasury fund has low expenses.

The supersafe. They invest only in U.S. Treasury bills and buy no Treasury derivatives. In general, investors earn less than they would in other funds. An exception could be an investor in a high-tax state such as California, Massachusetts, or New York. Dividends paid by Treasury funds are exempt from state and local taxes. As a result, they may net you more than funds invested in taxable corporate securities, especially if the Treasury fund has low expenses.

The plenty safe. These mixed funds buy Treasury securities and corporate securities too. They usually yield 0.25 to 0.5 percentage point more than pure Treasury funds, so you’re gaining $12.50 to $25 a year on a $5,000 investment. In my opinion, mixed funds are safe enough. Tax-exempt money funds, invested in short-term municipal securities, are plenty safe too.

The plenty safe. These mixed funds buy Treasury securities and corporate securities too. They usually yield 0.25 to 0.5 percentage point more than pure Treasury funds, so you’re gaining $12.50 to $25 a year on a $5,000 investment. In my opinion, mixed funds are safe enough. Tax-exempt money funds, invested in short-term municipal securities, are plenty safe too.

The probably safe. The highest-yielding money funds buy corporate securities and follow slightly riskier strategies. Reserve Primary Fund strayed into this area. So far, it has been the only one to lose money for investors, but it probably won’t be the last. If you buy a high yielder, be sure that it’s sponsored by a major financial institution that will step in if anything goes wrong.

The probably safe. The highest-yielding money funds buy corporate securities and follow slightly riskier strategies. Reserve Primary Fund strayed into this area. So far, it has been the only one to lose money for investors, but it probably won’t be the last. If you buy a high yielder, be sure that it’s sponsored by a major financial institution that will step in if anything goes wrong.

Regardless of the type of fund you’re interested in, don’t break your neck hunting for the highest payer. There’s always a different name at the top of the list, depending on each fund’s holdings and how fast it responds to daily changes in interest rates. I’d use six criteria in choosing a fund:

1. Are its expenses low? You’ll find the answer in the prospectus, in the table that shows all the fees and expenses. Managers who charge 0.5 percent of assets or less have a good shot at being top performers. Fees of 1 percent or more usually mark the funds that do the worst. Some funds with low expense ratios levy separate service charges, such as $2 per check or $5 per telephone transfer. If those fees were figured into the expense ratio, the fund would show a slightly higher cost. Some funds waive part of their fees temporarily to produce a competitive yield. When fees return to normal, your yield will drop. In general, large money funds are more cost efficient than small ones and ought to cost you less.

2. Does it fit your purse? You should have no problem meeting the fund’s minimum balance and check-writing rules.

3. Is it handy? If you invest with a particular mutual fund group or stockbrokerage firm, you’ll probably use the firm’s own money fund as a place to park cash.

4. What’s the fund’s average maturity—meaning, how long does it take for its average investment to come due? The shorter the term, the less risk the fund takes. Under proposed SEC rules, average maturity generally can’t exceed 60 days. (An average of 75 days is also under discussion.) Most funds post even shorter terms.

5. Does the fund belong to a major financial organization—a mutual fund group, a large brokerage house, an insurance company? This is your equivalent of deposit insurance. So far, these money fund sponsors have always paid for their mistakes rather than saddle their shareholders with a loss. A fund without major sponsorship, such as Reserve Primary, might not be able to cover a major error’s cost.

6. Are you comfortable with the fund’s investment policies? Safety is the watchword here, but that means different things to different people. You might want a fund that buys only Treasury bills. In a broader-based fund, you might want certificates of deposit only from the soundest banks and a limited amount of commercial paper.

As for derivatives, some of them aren’t particularly dangerous. Others can lose an unexpected amount of value when interest rates suddenly change.

How do you find out what a money fund buys? There’s only one way: read the prospectus. For safety, a suitable disclosure is, “This fund does not invest in derivatives.” Funds that devote many paragraphs to derivatives may be running more risks than even the managers realize.

Funds that consistently pay higher yields than the competition are the ones taking higher risks. And why would you take any risks at all? On $5,000, the difference between 3.5 and 3.1 percent comes to $20 a year. Big deal. If you’ve got $5 million, that 0.4 percent is worth a tidy $20,000—but short of that, why mess around?

A note about tax-exempt money market funds: Some people will do anything to beat Uncle Sam out of a few bucks, even if it costs them money. They buy a tax-exempt fund even if they’d do better in a taxable one. Look at a tax-free fund only if you are in a middle or high federal tax bracket (at this writing, 25 percent and up).

Here’s how to figure whether you’ll net more money from a tax-exempt fund than a taxable one: Subtract your combined state and federal tax bracket from 1.00. Divide the result into the current yield of the tax-exempt fund you’re looking at. The result is your break-even point. If you can find a taxable fund paying more than the break-even point, buy it.

For example, say you’re in the 25 percent bracket and are considering a fund that yields 2.5 percent. Subtracting 0.25 from 1.00 gives you 0.75. Dividing 2.5 by 0.75 gives you 3.33 percent. A taxable fund paying more than 3.33 percent will yield you more, after federal taxes, than the tax-free fund.

Four alerts:

1. A general tax-exempt fund includes the securities of many states. Your state may tax the interest on out-of-state bonds, making these tax exempts less attractive.

2. Single-state funds exist for states with higher taxes (California, Ohio, New Jersey, New York, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, among others). Your dividends should be entirely tax exempt. You take on slightly more risk, however, because you’re not diversified.

3. U.S. government money market funds include a mix of government securities, only some of which are state tax–exempt. Your fund should tell you what’s reportable in your state.

4. Some state and local securities are considered private purpose. That subjects them to the alternative minimum tax, as long as it survives. Ask about this if you’re in an AMT bracket (you know who you are!).

Beware of look-alike money market funds! They yield more than regular funds because they’re invested in the securities of a single company, such as Ford Motor Credit Company or GMAC Financial Services. At this writing, the Ford and GMAC notes are paying the interest due, despite their ties to the shrinking auto industry, but the notes are worth much less than you paid. Money funds need to be diversified to be acceptably safe—or, like bank money market accounts, they need to be federally insured. Check the money fund industry’s current average yield at iMoneyNet (www.imoneynet.com), and be suspicious of any “money account” that pays more.

Beware of “enhanced” cash funds! They’re diversified, but they invest in securities maturing in up to a year instead of super-short-term 30- to 60-day securities. If interest rates rise, the enhanced funds may lose money—not a lot, but enough to notice. Enhanced funds are fine for people who want to take a little risk in the hope of earning a higher return. But they’re not for savers who intended to keep their money safe.

Beware any investment that claims to act like a money fund while paying a sharply higher yield. That was the promise of the complex instruments called auction rate securities. They yielded high returns for 20 years. Then the market froze and investors couldn’t get their money out. Don’t play games with money fund look-alikes. For liquid savings, stick with the real thing.

Here I count everything from college tuition due next fall to the down payment on the house you hope to buy the year after next. You can’t risk losing a penny of it, so you can’t afford to play around. On the other hand, neither should these funds nap in a low-interest savings account. By choosing a guaranteed investment that pays a higher interest rate, you’ll pile up savings faster.

Most of you will agree with me about keeping six-month money safe. But five years sounds a lot further away. Why not invest in stocks for growth? Here’s my argument: Stock prices rise and fall. For money you’ll absolutely need, it’s the “fall” you have to worry about. If you have the bad luck to invest just before stocks go into a decline, you’ll lose some of your principal, which could be disastrous if that money is needed to pay a specific bill. Since 1929, it has taken investors an average of nearly four years to get even again after a major stock market drop, assuming that dividends were reinvested.

If you’re more adventurous, you might decide to keep only two-year money totally safe. Since World War II, the average stock market dip and recovery took just over two years. Still, the second longest dip and recovery on record started in August 2000 and lasted until October 2006—more than six years. And then the market fell again, with years of recovery still ahead! How much risk are you willing to take with money you must have within a shorter period of time?

Certificates of Deposit. With a CD, you put your money in a bank or credit union for a fixed term. You normally earn a higher interest rate than you would in a bank money market deposit account.

Some people hate CDs because they feel that their money is locked away. But it’s not. You can break into a certificate anytime you want before maturity. The worst that can happen is that you’ll pay an interest penalty. Big deal. That’s nothing compared with the interest you lose by keeping too much money in a low-interest savings account. If you balance risk and reward, CDs are a shoo-in. Most savers will not face an emergency need for cash. You’ll hold your CD to maturity and earn more interest along the way. Note that CDs at online banks usually pay more than those at traditional banks.

Institutions may offer standard terms for CDs, such as 6, 12, or 30 months. Some let you pick whatever term you like. Normally, the longer the term, the more interest you earn. For how to get higher interest through laddering CDs, see page 67.

U.S. Treasury Securities. A Treasury security is the fruit of federal deficit spending. When the government spends more money than it collects in taxes, it has to borrow to make up the difference—and it borrows from you, by selling you Treasuries. You are actually lending money to Uncle Sam for a fixed period, earning interest all the while.

To buy Treasuries, go online to TreasuryDirect (www.treasurydirect.gov) and set up an account. You can do it in five minutes flat. If you aren’t online, write to the nearest Federal Reserve Bank (they’re listed on page 229) for the forms you need. The job is not exactly a brain buster and there are no charges to pay when you buy direct from the Fed. Still, I can hear some of you groaning. If this sounds like too much work, a bank or a stockbroker will buy Treasuries for you for a fee. Or you can buy a TIPS mutual fund (see page 226).

What’s your reward for becoming a Treasury investor? In most states, an instant break on your income taxes. The interest you earn on U.S. Treasury securities, while taxed at the federal level, cannot be taxed by states and cities. So you might earn a higher after-tax return than you’d get from the average certificate of deposit.

The minimum investment for Treasuries is $100. The yield is set through public auction by the big institutions that put in bids. When you buy directly from the Federal Reserve, you piggyback on what the institutions pay. You’ll find the auction dates at TreasuryDirect.

Which Treasuries to buy depends on when you’ll want the money:

Treasury bills mature in four weeks, three months, or six months. You send the Fed a certified check for the bill’s face amount or authorize a direct payment by your bank. Immediately after the auction you get a discount payment back, representing the difference between the face value of the bill and the lower auction price. At maturity, you’re paid the face value. Your profit is the difference between the two. For example, say you send $1,000 for a six-month bill that sells for $950. The Treasury sends you $50 back. At maturity, your T-bill pays $1,000, for a $50 profit.

There are two ways of measuring your return on investment. The newspaper stories generally highlight the discount rate, which compares your profit ($50) with the bill’s face value ($1,000). By this measure, you’ve apparently earned 5 percent.

But that understates what you’ve really earned. After all, you didn’t put up the full $1,000. In this example, you invested only $950. A $50 return on $950 comes to about 5.3 percent. That’s called the coupon-equivalent yield and is the true measure of your return. Use it to compare the profit in Treasury bills with what you might get from alternative investments, such as bonds and CDs. You’ll find the coupon-equivalent yields on the Web site TreasuryDirect.

T-bills let you play income tax games. If you buy a security today that matures in the next calendar year, your interest income falls into that year, so you defer the tax you owe. Note that your taxable profit is not the discount check that the Treasury sends you right away. It’s the profit you make when the bill matures.

Treasury notes mature in two, three, four, five, seven, or ten years. Different maturities are auctioned at different times (you’ll find the dates at TreasuryDirect). Just authorize a withdrawal from your bank account for the face amount of the notes you want, or mail a check. Immediately after the auction, you will usually get a few dollars back because the notes sold for a hair less than their face value. Only one yield is reported (there’s no coupon-equivalent yield to worry about, as with Treasury bills). Interest is paid on your full investment twice a year.

When choosing Treasury notes, pick a maturity that coincides with the date you’ll want to use the money.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) are issued for terms of 5, 10, and 20 years. They protect both your principal and interest from inflation. Your principal rises by the percentage change in the consumer price index (the increase is compounded daily and added to the value of your bond every six months). The interest rate is fixed, but it’s paid on a rising amount of principal, which means that your income, in dollars, increases too. If inflation rises by 1 percent, the value of your TIPS will also rise by 1 percent.

Your principal’s increase in value is taxable in the current year, even though you don’t get the money until the bond matures or until you sell before maturity. For this reason, investors prefer to hold individual TIPS in tax-deferred retirement accounts. Most TIPS mutual funds work differently. They pay out the gain in your principal in monthly or quarterly installments, so you have cash in hand when your taxes come due.

Initially, TIPS pay a lower interest rate than you could earn on fixed-rate Treasuries, but they’ll pay more if inflation rises faster than people generally expect. For help in choosing between TIPS and fixed-rate Treasuries, see page 929.

Shorter-term zero-coupon Treasuries can be good ways to save over four years. A zero is a Treasury note bought for less than its face value. It pays no current interest (also called the “coupon”). Instead you buy the note for less than its face value. Every year the interest builds up within the bond until it reaches face value at maturity. For example, you might pay $865 (before sales commissions) for a zero that will be worth $1,000 in five years. That’s an annual compound yield of 4.8 percent.

Zeros are sold by stockbrokers and banks, not through TreasuryDirect. Just be sure that you can hold the note until its maturity date. You may lose money if you have to sell a zero before maturity.

What’s nice about zeros is that they reinvest your interest at the same rate that you’re earning on the bond itself. With the zero just discussed, for example, you earn 4.8 percent on every interest payment. With other bonds, you’re paid in cash and have to reinvest the money yourself. Small payments (if not spent) will probably land in a bank account or money market fund, where they’ll generally earn much less than you’re earning on the bond itself.

What’s bad about zeros is that you’re taxed every year on the interest that builds up, even though you don’t physically receive the money. If you’re younger and will want the cash at maturity, you’ll have to grin and bear it. If you’re older and can wait for the cash until after age 59½, buy your zeros in a tax-deferred retirement account.

A four-year zero-coupon Treasury is a reasonable bet for your teenager’s education fund. Buy one when the child is 14 years old, to cash in when he or she reaches 18. Your money is safe, and the earnings should compound at a reasonable rate of interest. (For younger children, don’t buy zeros, buy stock-owning mutual funds—see page 845.)

Long-term zeros are another story. Like other Treasury bonds, they’re generally wrong for short-term savers. When interest rates rise, zeros lose value faster than other bonds do, which can hurt you if you have to sell before maturity. For more on zeros, see page 945.

Treasury bonds have the longest maturities, generally up to 30 years. They’re auctioned in the same way as Treasury notes, with interest payable twice a year. I mention them here only to be orderly. Long-term Treasuries aren’t the right place for savings you might have to tap. If you sell them before maturity, you’ll be exposed to the hard, cold winds of the open market, where your bond might bring less than you originally paid. The newer inflation-indexed Treasuries don’t vary in price as much as conventional Treasuries, but they pay a smaller current income. For ways to use long-term Treasury bonds, see page 921.

— How to Buy Treasuries —

There’s no such thing as a physical Treasury certificate. Your purchase is recorded. You get a statement. But you don’t get the thing itself to hold in your hand because there is no “thing itself.” A Treasury certificate has become a concept in the mind and a byte in the computer.

You can buy Treasuries online at TreasuryDirect, through a Federal Reserve Bank (page 229), or through a commercial bank or stockbroker. Which to choose depends on the kind of investor you are. (Note that TreasuryDirect is only for personal investing. You can’t buy for your Individual Retirement Account.)

Savers: Buy Through the Fed When you buy online or through the Fed, you pay no fees or commissions on securities held to maturity. Every penny you earn in yield is yours to keep. The system, called TreasuryDirect, is entirely Web based. Older accounts, now called Legacy Treasury Direct, can still be handled by mail.

With TreasuryDirect, you open an account with the Federal Reserve, which keeps track of all your transactions. You’ll be asked for your bank’s nine-digit American Bankers Association routing transit number. That’s the mystery number on the bottom of any check or deposit slip. Usually it’s on the left; your account number is on the right.

To buy, you authorize the Treasury to withdraw the money from your bank account. Your interest earnings can be paid electronically into your bank or mutual fund account. Ditto the proceeds when your securities mature. If you’ll want to reinvest, check the date when the proceeds will be paid. Tell the Treasury to return to your account that day and withdraw the money again for a new purchase. You can also have the proceeds parked in a non-interest-bearing Treasury security (called a certificate of indebtedness), waiting for reinvestment.

Investors with legacy accounts still have to send a tender form and certified check for their purchases. However, you can arrange for your maturing Treasury bills to be reinvested automatically, for the same term. You may find it convenient to convert from a legacy account to the new TreasuryDirect, so that you can operate entirely by Web.

If you want to sell a security prior to maturity, you have to mail a form to the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank (page 229), which will get three price quotes from dealers and sell for you at the highest bid. The fee for this service: $45.

Speculators: Buy Through Banks or Stockbrokers A speculator buys and sells long-term Treasury bonds, hoping to earn a profit from changes in interest rates. This means selling securities before they mature and at a moment’s notice. Only commercial banks or stockbrokerage firms do that. They also let you order by phone and will lend you money against your securities. Sales commissions: a minimum of $15 to $60 every time you buy or sell. Online brokers may let you buy large amounts of Treasuries free.

It makes no sense at all to use brokerage firms for small orders of short-term Treasury securities. The commission might slash your yield by 0.5 percent on a six-month T-bill. On larger purchases or on longer-term securities, however, brokerage fees don’t take such a big bite.

Buying Zero-Coupon Treasuries They’re bought through stockbrokers. But some firms clip you for a higher price than you should pay. They trap you by quoting a dollar figure—“only $865 for these bonds”—without telling you what the bonds are priced to yield. That might saddle you with an unfairly low rate of return.

A smart investor buys through a discount broker. Ask for both the dollar price and the net yield to maturity after sales charges, which is what the bond pays over its full term.

Risk part of it in the stock market or other growth investment—the amount depending on your age. Otherwise, you’ll never get ahead of inflation and taxes.

But you might want to keep even some of your long-term money absolutely safe. For this purpose, two suggestions:

Five-Year Certificates of Deposit or Treasury Notes, Continually Reinvested. They should roughly preserve your purchasing power, provided that you reinvest all of the interest as well as the principal. You’re buying for only five years at a time, so you’ll probably be able to hold each note until maturity. That’s important, as you might lose money if you have to sell before the notes mature. You can ladder Treasury bills and notes just the way you do certificates of deposit (explained on page 67).

U.S. Savings Bonds. Savings bonds, although issued by the U.S. Treasury, are not what investors know as Treasury securities. Treasuries pay competitive interest rates and can be bought and sold on the open market. Savings bonds don’t and can’t. They’re a special type of bond, sold principally to small investors. You pay no fees to buy or sell. You cannot lose money on savings bonds regardless of general market conditions.

Savings bonds come in two types: (1) The traditional Series EE bonds, which pay a fixed rate for the life of the bond, and (2) Series I bonds, whose yields adjust for inflation. They pay a low fixed rate, good for the life of the bond, plus a floating rate linked to the consumer price index. The floating rate changes every May 1 and November 1. Interest on both types of bonds is compounded semiannually and credited monthly. I bonds usually yield more than EE bonds, but not always.

The government limits how much you can put into savings bonds every year. At this writing, it’s just $5,000, for a bond with a $10,000 denomination. Fixed-rate Treasuries or TIPS pay higher interest rates, but savings bonds have some special virtues:

You can earn these rates on a very small amount of money. The cheapest bond costs $25 ($50 if you buy through payroll deduction).

You can earn these rates on a very small amount of money. The cheapest bond costs $25 ($50 if you buy through payroll deduction).

You can tax-defer the interest until the bonds are finally cashed in or until they reach their final maturity.

You can tax-defer the interest until the bonds are finally cashed in or until they reach their final maturity.

You receive no money until redemption, so you can’t go out and spend the interest. Savings bonds (as well as zero-coupon bonds and TIPS) force you to save.

You receive no money until redemption, so you can’t go out and spend the interest. Savings bonds (as well as zero-coupon bonds and TIPS) force you to save.

If you bought savings bonds after December 31, 1989, and use the proceeds to cover tuition for qualified higher education, you might pay no income tax on the interest you earn (page 678).

If you bought savings bonds after December 31, 1989, and use the proceeds to cover tuition for qualified higher education, you might pay no income tax on the interest you earn (page 678).

There are four ways of buying savings bonds, with different rules.

1. You can buy online through TreasuryDirect. You won’t get a paper bond. Instead your purchase will be held in your electronic account. With investments over $25, you can buy to the penny; for example, you could get a bond worth $70.45. Interest is paid on the purchased amount.

2. You can buy paper bonds through most banks and some credit unions. You’ll receive the bond in about three weeks. Paper bonds are sold in denominations of $50, $75, $100, $200, $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000, at a 50 percent discount from face value. The $100 bond costs $50; the $500 bond costs $250. Each month’s interest is added to the bond’s redemption value. Since December 11, 2001, paper EE bonds bought through banks have been stamped “Patriot bonds.” That’s just a name. They’re the same as any other EE bond.

3. You can buy through a payroll savings plan if your company offers one. There are plans for both paper and electronic bonds through TreasuryDirect.

4. You can check a box on your tax return, asking that your refund be paid in savings bonds instead of in cash.

No matter how you buy, the interest rate will be the same. You must hold the bond for at least 12 months. After that, you may cash it in whenever it suits you. As with other Treasury securities, you owe only federal income taxes on the interest you earn, no state and local income taxes.

Plan to hold for at least five years. There’s a three-month interest penalty on bonds redeemed within that period. If you sell after the first five years, you’ll get whatever the bonds have earned since the month you bought. If you hold for 20 years or more, the government offers a guarantee: your EE-bond investment will—at minimum—double in value. That gives super-long-term holders a base rate of 3.5 percent, and higher if long-term interest rates stay above that level. For a recorded announcement of current savings bond interest rates, call toll-free 800-US-BONDS. Or visit the Web site TreasuryDirect.

Here’s a subject that’s widely misunderstood. Unlike certificates of deposit, savings bonds do not have to be held until a particular maturity date. You redeem them at your convenience, receiving whatever they’re worth at the time.

This misunderstanding arises because of the way that paper EE bonds are sold. You buy at a 50 percent discount, paying $50 for a $100 bond. So you naturally might think that you have to hold until your bond is worth $100. Not so. You have no idea when it will be worth $100 because that depends on what happens to interest rates. At the very worst, you’d get $100 after 20 years because that’s your government guarantee. But the bond might reach $100 in value sooner than that. In any event, none of this matters. You just cash in the bond when you need the money and get all your principal back plus any interest due. You do not have to hold for 20 years.

Here are the maturities for savings bonds and what they mean:

1. Original maturity. This is the maximum time it will take for a paper bond to reach its face value. For newly issued bonds, that’s 20 years, even though they may actually reach face value sooner.

2. First extended maturity. This lasts for 10 years after the original maturity date.

3. Additional extended maturities. Older bonds with original maturities shorter than 10 years get an additional extension, allowing them to pay interest for 30 or 40 years.

4. Final maturity. This is the date after which the bond will no longer earn interest. On newly issued bonds, the final maturity—printed on the face of the bond—is 30 years away. Here are the final maturity dates for all other bonds (note that the oldest of these are no longer earning interest):

Series E bonds issued earlier than December 1965—40 years after their issue date

Series E and EE bonds and Freedom Shares issued after November 1965—30 years after their issue date

Series H bonds issued between 1959 and 1979—30 years after their issue date

Series HH bonds issued since 1980—20 years after their issue date (new Series HH bonds are no longer being issued)

5. Maturities on bonds bought through TreasuryDirect. They’re a flat 30 years, with no complications.

Don’t hang on to old savings bonds that aren’t paying interest anymore! Cash them in and get the money. Ask older family members whether they have any E bonds stashed away and check the dates. When an E or EE bond reaches its final maturity, all the unreported interest becomes taxable even if you don’t turn it in. Here are the dates for the bonds no longer earning interest: those issued between May 1941 and May 1963 and those issued between December 1965 and May 1973. Americans now hold more than $12 billion in bonds that are no longer earning interest! Savings Notes, also called Freedom Shares, are also no longer earning interest.

— Some Angles to Savings Bond Investments —

An individual can invest up to $5,000 in a calendar year in each series (EE and I) and in each format (paper and electronic). That’s a total of $20,000 or $40,000 for two co-owners. Paper savings bonds bought as gifts aren’t included in your annual limit.

An individual can invest up to $5,000 in a calendar year in each series (EE and I) and in each format (paper and electronic). That’s a total of $20,000 or $40,000 for two co-owners. Paper savings bonds bought as gifts aren’t included in your annual limit.

Bonds earn interest from the issue date, which is always the first day of the month you bought. If you buy a bond on the last day of the month, it will be backdated to the first day. Interest on new bonds is credited every month.

Bonds earn interest from the issue date, which is always the first day of the month you bought. If you buy a bond on the last day of the month, it will be backdated to the first day. Interest on new bonds is credited every month.

Interest on older EE bonds—those bought prior to May 1, 1997—is normally credited every six months. You earn more money by cashing them just after the crediting date rather than just before. You can find that date at TreasuryDirect.

To find out what your bonds are worth today, go to the pages for EE or I bonds at TreasuryDirect. Click on Redeem and look for the Savings Bond Calculator.

To find out what your bonds are worth today, go to the pages for EE or I bonds at TreasuryDirect. Click on Redeem and look for the Savings Bond Calculator.

You can redeem just part of a bond if its face value is at least $50 for Series E bonds, $75 for Series EE or Series I, and $1,000 for Series H or HH. For example, a bond worth $1,000, with an accrued value of $700, can be turned in for $700 in cash and $300 in bonds. The new bonds will have the same issue date as the old one did.

You can redeem just part of a bond if its face value is at least $50 for Series E bonds, $75 for Series EE or Series I, and $1,000 for Series H or HH. For example, a bond worth $1,000, with an accrued value of $700, can be turned in for $700 in cash and $300 in bonds. The new bonds will have the same issue date as the old one did.

If you buy a savings bond in your own name, you control it completely. If you name a beneficiary on an EE bond, you can change the beneficiary whenever you want just by filling in Form PD 4000 (available at TreasuryDirect or from many of the agents who issue savings bonds). The rules are different for the older, Series E bonds. With them, the beneficiary has to agree to being removed by signing Form PD 4000.

If you buy a savings bond in your own name, you control it completely. If you name a beneficiary on an EE bond, you can change the beneficiary whenever you want just by filling in Form PD 4000 (available at TreasuryDirect or from many of the agents who issue savings bonds). The rules are different for the older, Series E bonds. With them, the beneficiary has to agree to being removed by signing Form PD 4000.

If you buy a savings bond in joint names, both owners have to agree to any changes. But either one of you can cash in the bond and the other doesn’t have to know. Whoever holds it, controls it.

If you buy a savings bond in joint names, both owners have to agree to any changes. But either one of you can cash in the bond and the other doesn’t have to know. Whoever holds it, controls it.

The person whose money bought the bond is called the principal co-owner, and all the income should be taxed to him or her. If both of you contributed, there is no principal co-owner and taxes should be allocated according to what percentage each of you paid. As a practical matter, however, the tax is usually paid by the person who redeems the bond.

The person whose money bought the bond is called the principal co-owner, and all the income should be taxed to him or her. If both of you contributed, there is no principal co-owner and taxes should be allocated according to what percentage each of you paid. As a practical matter, however, the tax is usually paid by the person who redeems the bond.

If you buy a paper bond as a gift, you don’t need the recipient’s Social Security number; you can use your own. Gifting is more complicated, however, through TreasuryDirect.

If you buy a paper bond as a gift, you don’t need the recipient’s Social Security number; you can use your own. Gifting is more complicated, however, through TreasuryDirect.

If the bond is a gift, the interest is taxed to the person receiving it. In theory, the purchaser should sometimes pay the tax. For example, the interest is taxable to you if you buy a bond as a gift for a child and name yourself co-owner. Nevertheless, if the child grows up and redeems the bond, the 1099 will be issued in the child’s name.

If the bond is a gift, the interest is taxed to the person receiving it. In theory, the purchaser should sometimes pay the tax. For example, the interest is taxable to you if you buy a bond as a gift for a child and name yourself co-owner. Nevertheless, if the child grows up and redeems the bond, the 1099 will be issued in the child’s name.

The interest earned on savings bonds is normally tax deferred. But children who own bonds and are in low (or zero) brackets should not defer. Report the interest now, when little or no tax will be due, rather than wait until the child grows up. To get this easy tax break on bonds bought this year, file a return for the child showing how much the EE bonds gained in value (your bank or credit union may have this information; you can also use the Savings Bond Calculator at TreasuryDirect). No further tax returns have to be filed for those particular bonds as long as the child owes no tax. In any year the child does owe a tax, his or her return will have to report that year’s gain in the EE bonds’ value.

The interest earned on savings bonds is normally tax deferred. But children who own bonds and are in low (or zero) brackets should not defer. Report the interest now, when little or no tax will be due, rather than wait until the child grows up. To get this easy tax break on bonds bought this year, file a return for the child showing how much the EE bonds gained in value (your bank or credit union may have this information; you can also use the Savings Bond Calculator at TreasuryDirect). No further tax returns have to be filed for those particular bonds as long as the child owes no tax. In any year the child does owe a tax, his or her return will have to report that year’s gain in the EE bonds’ value.

What if your child deferred income taxes in the past and now wants to pay them currently? In the year that you switch, all past gains must be reported.

What if the child has been paying taxes currently and now wants to defer (deferral is smart for children who have enough unearned income to be taxed in their parents’ bracket—page 91)? File Form 3115, Application for Change in Accounting Method, with the child’s tax return for the year you want the change to start.

Keep copies of all the child’s tax returns. When the bonds are cashed in, you or your child must be prepared to prove which gains were previously reported. Otherwise the IRS might conclude that the child owes taxes on all of the profits.

Bonds may be held by the trustee of your trust. But the trust can’t be co-owner or beneficiary.

Bonds may be held by the trustee of your trust. But the trust can’t be co-owner or beneficiary.

What if you die holding savings bonds? Your executor or trustee has two tax choices:

What if you die holding savings bonds? Your executor or trustee has two tax choices:

1. All the income to date can be reported on your final tax return and the taxes paid. The beneficiary who receives the bonds should then be taxed only on the income earned from that point on. To avoid being taxed on the full amount at redemption, however, the beneficiary must have a copy of the tax return to prove how much was previously paid.

2. The bonds can be passed to the beneficiary as is, with all the tax deferred. When the beneficiary redeems, he or she pays the entire tax.

When one owner dies, a co-owner takes over the bonds automatically. But they should be reissued in the surviving owner’s name (or in the name of the surviving owner—named first—plus a new co-owner). If you inherit a savings bond that was issued to someone else, you can also have it reissued in your name or in your name plus a co-owner.

When one owner dies, a co-owner takes over the bonds automatically. But they should be reissued in the surviving owner’s name (or in the name of the surviving owner—named first—plus a new co-owner). If you inherit a savings bond that was issued to someone else, you can also have it reissued in your name or in your name plus a co-owner.

On reissue, the bond’s final maturity remains the same, interest accumulates as usual, and no taxes are due. However, you can’t have a bond reissued if it’s close to its final maturity. Such bonds must be redeemed.

To redeem a bond after a death, or have it reissued in a new name, a beneficiary has to produce a death certificate. A co-owner can redeem without a death certificate but will need it for reissue.

If you inherit a bond and die without having the former owner’s name removed, your heirs will have to produce two death certificates—yours and the former owner’s—before they can redeem the bonds.

Co-owners can redeem their bonds at any bank that handles that business. If you inherited someone else’s bond, however, you have to redeem through a Federal Reserve Bank or the Bureau of the Public Debt (page 237).

If you die without a will, your family will have to suffer a mess of paperwork (Form PD 5336) before your savings bonds can be passed to a new owner. So don’t.

If you die without a will, your family will have to suffer a mess of paperwork (Form PD 5336) before your savings bonds can be passed to a new owner. So don’t.

If you co-own bonds that cannot be found after the other owner’s death, file a lost-bond claim with the Bureau of the Public Debt and have them reissued. You may discover that the other owner cashed them without telling you.

If you co-own bonds that cannot be found after the other owner’s death, file a lost-bond claim with the Bureau of the Public Debt and have them reissued. You may discover that the other owner cashed them without telling you.

For a reissue form (PD 4000), ask a bank that handles savings bond sales, call the nearest regional Federal Reserve bank, or go online to Treasury-Direct. The forms are fairly simple. If you have a question, call the nearest Fed. Your bank might also help you—sometimes free, sometimes for a fee.

For a reissue form (PD 4000), ask a bank that handles savings bond sales, call the nearest regional Federal Reserve bank, or go online to Treasury-Direct. The forms are fairly simple. If you have a question, call the nearest Fed. Your bank might also help you—sometimes free, sometimes for a fee.

What if you want to give away a savings bond? Don’t have it reissued in the new name. If you do, you’ll owe income taxes currently on the accumulated interest even though that interest won’t actually be paid out. Years later, when the recipient redeems the bond, all the interest will be taxable unless he or she can prove that part of the tax was already paid. These rules also apply if you’re the bond’s principal co-owner (listed first on the bond’s face) and want to reissue it solely in the name of the other owner.

What if you want to give away a savings bond? Don’t have it reissued in the new name. If you do, you’ll owe income taxes currently on the accumulated interest even though that interest won’t actually be paid out. Years later, when the recipient redeems the bond, all the interest will be taxable unless he or she can prove that part of the tax was already paid. These rules also apply if you’re the bond’s principal co-owner (listed first on the bond’s face) and want to reissue it solely in the name of the other owner.

The best way of making the gift is to add the lucky person to the bond as co-owner. There are no tax consequences. The co-owner can cash in the bond whenever he or she wants, deferring taxes until that time. There’s also no tax if you remove the second co-owner’s name or have the bond reissued in the name of the trustee of your trust.

What if you marry and change your name? You don’t have to get your savings bonds reissued. When you cash them in, just sign the bond with both your maiden name and your married name.

What if you marry and change your name? You don’t have to get your savings bonds reissued. When you cash them in, just sign the bond with both your maiden name and your married name.

What if you buy a bond and it comes with your name spelled wrong or the wrong date on it? Don’t fix it yourself. You cannot redeem a bond that has been altered. Return it to the place that issued it and get the error fixed.

What if you buy a bond and it comes with your name spelled wrong or the wrong date on it? Don’t fix it yourself. You cannot redeem a bond that has been altered. Return it to the place that issued it and get the error fixed.

You’re not allowed to borrow against your savings bonds.

You’re not allowed to borrow against your savings bonds.

If you lose a bond, it’s easy to replace as long as you know its face value (denomination), issue date, registration number, and the name or names in which it was issued, their addresses, and their Social Security numbers. Photocopy each bond you own or list the critical information. Keep these records in your safe-deposit box or fireproof home safe.

If you lose a bond, it’s easy to replace as long as you know its face value (denomination), issue date, registration number, and the name or names in which it was issued, their addresses, and their Social Security numbers. Photocopy each bond you own or list the critical information. Keep these records in your safe-deposit box or fireproof home safe.

If you don’t keep good records, the Treasury may be able to trace the bond for you, especially if it was issued after January 1974. All those savings bonds have Social Security numbers on them. What’s lost can be found if the Treasury knows the Social Security number of the first owner named on the bond.

If you don’t keep good records, the Treasury may be able to trace the bond for you, especially if it was issued after January 1974. All those savings bonds have Social Security numbers on them. What’s lost can be found if the Treasury knows the Social Security number of the first owner named on the bond.

Older bonds sometimes carry Social Security numbers too. If not, the Treasury can’t hope to trace ownership unless it knows the bond’s serial number or the name on the bond and that person’s address when it was bought.

A lost bond can be replaced at no cost to you. If you’re replacing a partly burned or mutilated bond, send the Bureau of the Public Debt the remains. The form used for replacement is PD 1048, available online or from many commercial banks, a regional Federal Reserve bank (page 229), or the Bureau of the Public Debt. Replacement takes anywhere from 8 to 24 weeks.

If you replace a bond and the original turns up, it must be surrendered for cancellation. The government won’t let you cash the same bond twice. If you try, you’ll find out that Big Brother knows.

If you’re in a payroll deduction plan, you can buy fractions of bonds. For example, you might have $25 taken from every paycheck and credited toward the $50 cost of a $100 bond. After two payments you should be issued your bond. Arrange to have the bonds mailed to you and check that the amounts are right. Your only proof of purchase is normally the deduction shown on your pay stub, and it’s up to you to check that you received what you paid for. To simplify the job, buy a full bond with each deduction rather than a fraction of a bond. If your bonds don’t arrive or you get the wrong denominations, query your payroll department, which should initiate a claims procedure.

Any bank authorized to sell EE bonds can also cash them in for you, although some redemptions, such as those by a guardian or trustee, may have to be handled directly by the government. Try to redeem at a place where you’re known, such as your own bank. If you’re not known, you will need documentary identification—a picture driver’s license, an employee card with your picture on it—and may be limited to redeeming only $1,000 worth of bonds per day.

Any bank authorized to sell EE bonds can also cash them in for you, although some redemptions, such as those by a guardian or trustee, may have to be handled directly by the government. Try to redeem at a place where you’re known, such as your own bank. If you’re not known, you will need documentary identification—a picture driver’s license, an employee card with your picture on it—and may be limited to redeeming only $1,000 worth of bonds per day.

Your accumulated bond interest becomes taxable when you cash in the bonds. So if possible, don’t redeem them in a high-earning, preretirement year. Wait until well after you retire, when your income may have dropped.

Your accumulated bond interest becomes taxable when you cash in the bonds. So if possible, don’t redeem them in a high-earning, preretirement year. Wait until well after you retire, when your income may have dropped.

A tip on older savings bonds, bought prior to May 1, 1995: these bonds have interest rate guarantees ranging from 2.5 to 4 percent. Don’t cash in an older bond without ascertaining its guarantee. It may be earning more than any other fixed-income investment you own. To check the guarantee, consult TreasuryDirect’s online “Table of Guaranteed Minimum Rates and Original Maturity Periods.”

A tip on older savings bonds, bought prior to May 1, 1995: these bonds have interest rate guarantees ranging from 2.5 to 4 percent. Don’t cash in an older bond without ascertaining its guarantee. It may be earning more than any other fixed-income investment you own. To check the guarantee, consult TreasuryDirect’s online “Table of Guaranteed Minimum Rates and Original Maturity Periods.”

— Where to Get Information on Savings Bonds —

You can’t rely on banks to answer your questions on savings bonds correctly, even if they handle them. The program is complex and the clerks may not be fully trained. You should go online to TreasuryDirect or get information brochures to research the bonds yourself. The Bureau of the Public Debt answers questions, handles problems, and mails out forms. You can order forms online or write to the Bureau’s Division of Customer Assistance at P.O. Box 7012, Parkersburg, WV 26106.

For a question about paper savings bonds, call the Savings Bond Processing Site. There are two numbers: 800-245-2804 and 800-553-2663.

If you don’t want to dig through all the numbers yourself, you can buy a personal savings bond report from SavingsBonds.com (www.savingsbonds.com). It tells you about each bond you own—interest rate, current value, maturity date, and so on. If you’re cashing bonds in, it will advise you on which ones to redeem first (those paying lower interest rates) and when to redeem them, to capture the final six-month interest payment. The Web site also contains plenty of free information.

You can get a similar report from the Savings Bond Informer at P.O. Box 11721, Monroe, MI 48161, or call 800-927-1901. If you want to look before you buy, the Informer will send you a free example.

I also recommend the Informer’s valuable reference book on how the bond program works, U.S. Savings Bonds. It was published in 1999 but comes with an update on all the latest changes, strategies, and interest rates. Cost: $19.95.

When you buy cash-value life insurance, you buy a kind of savings account that builds up over many years. But there are two fatal drawbacks to this form of savings: (1) Very little money normally accumulates in the early years. (2) To get at your money, you generally have to borrow it, paying interest as you go. If you choose the money fund option in a variable-life policy, the annual fees will virtually wipe out your yield. I’m all for good insurance, and, in a few cases, a cash-value policy may be exactly what you want. But if savings are your primary interest, look somewhere else.

When you’re young, you have to learn how to save. When you’re old, you have to learn how to stop. Many older people deny themselves comforts because they’re afraid to spend the money they have so carefully put aside.

Past a certain age, it’s time to spend your children’s inheritance, to give yourself the decent retirement you deserve. In chapter 30, you’ll find guidelines on how to spend your money without running out.