A House Is a Security Blanket

… Even If It Doesn’t Make You Rich

Home ownership is your only hope of living

“free” when you retire. Rent goes on forever.

Mortgage payments eventually stop.

A house may not be your best investment in the decade ahead. If the price drop starting in 2006 taught us anything, it’s that real estate doesn’t always go up. Over the time that you own your particular house, its value might rise, fall, or stall. You can’t predict.

But there are reasons other than profit for owning a home. You get tax deductions on mortgage interest and tax-free capital gains. You’re landlord free. You know the deep contentment of holding a spot of ground that others can enter by invitation only. You won’t lose your lease. You can renovate to suit. Your mortgage payments build a pool of usable savings that you otherwise might not have. A house is collateral for a loan. House payments often cost less than rent, after tax.

As a home owner, you have three principal goals. First, to choose a mortgage you know you can afford. Second, to grow your home equity, which you can use to improve your house or trade up to something better. Third, to pay off the mortgage so that, by the time you retire, you’ll own a home free and clear.

Smart home owners cherish their home equity. Defined, it’s the difference between your home’s market value and the balance owed on your mortgage. If the house is worth $350,000 and you took a $300,000 mortgage, you have $50,000 in equity. The greater your equity, the richer you are.

There are three ways for equity to grow: (1) The magical way, during real estate booms. Home prices rise because eager buyers bid them up. (2) The usual way, in normal times. Home prices rise modestly, while you lower your mortgage by paying down your debt. (3) You improve the property in some way. Most home owners benefit from all three.

There are four ways of losing home equity: (1) Home prices fall. Times have changed and buyers aren’t willing to pay as much as you did. (2) You borrow more money against your home by refinancing into a larger mortgage or taking a second mortgage, such as a home equity loan. (3) You let the property fall into disrepair. (4) Worst case—you run into financial trouble or the mortgage rate jumps up, you default on the monthly payments, and you lose the property.

During real estate booms, people get careless with their home equity. They throw it away by taking serial loans against the house and spending the money. Or they take an interest-only mortgage, never paying down the principal. They assume that rising home prices will replace the equity they’re destroying themselves. This works in boom times. But in normal times, when home prices are flat or rising only gently, you have to put money into repaying your mortgage to see your wealth increase.

19 Ways of Buying Your First Home

1. Save money for a down payment. People are doing it every day. No video toys. No dinners out. A cheaper apartment than you really could afford. A second job. A bigger savings account in place of a vacation. Down payments are higher today than they were in 2006 and 2007, but home prices are lower, so it’s easier to start than you think.

2. Visit the Mommy-and-Daddy Bank. Many adult children nowadays rely on their parents to lend or give them part or all of their first down payment. A parent who’s a gambler might even cosign your mortgage loan. (The M&D Bank may have to tell the lender, in writing, that the down payment is a gift.)

3. Move. If you can’t afford a house near Washington, D.C., or Los Angeles, think about Wisconsin or Tennessee. Think about it when you’re young and looking for your first job, because that’s often where you’ll buy your first home.

4. Commute. The further into the exurbs you’re willing to go, the cheaper the houses, although the more expensive the gasoline that gets you to work. Maybe you can telecommute.

5. Buy an older house. It might cost 15 to 20 percent less than a newly built house for the same floor space. The down payment will be lower too. You’ll have to spend some money repairing or updating the house, but at least you’re in.

6. Buy a wreck. If you can stand living in a construction site for a year or two and are handy with tools, you can buy a wreck cheaply and fix it up.

7. Lower your consumer debt. The less debt you carry, the better the terms you can get on a mortgage.

8. Make a deal with the seller. Ask if he or she will lower the price by enough to cover your closing costs. If you can’t get a big enough mortgage to pay the asking price, maybe the seller will take what you have and let you pay the additional money over one to three years. To guarantee payment, you’d give the seller a second mortgage or deed of trust against the house. (Be sure to disclose this arrangement to the bank.)

9. Get a low-down-payment loan backed by private mortgage insurance. In their dreams, lenders want 20 percent down, but they take less when you qualify for private mortgage insurance, as most borrowers do. If you quit paying and the house goes to a foreclosure sale, the insurer covers the lender’s loss. With this guarantee, the lender may accept 10 percent down or even less, depending on the size of your income and market conditions.

Your insurance premiums are usually bundled into your monthly mortgage payment, although sometimes the first-year cost has to be paid up front. The price depends on the type of loan and how much money you put down. Some insurers charge a fixed annual rate on the loan’s declining balance. Others charge roughly 0.3 to 0.9 percent of the original loan balance for the first 10 years, then perhaps 0.2 percent in subsequent years. There are dozens of permutations, including slightly higher rates in markets where housing prices are going down.

During the real estate boom, lenders offered an alternative to private mortgage insurance, known as a “piggyback loan.” You were given a first mortgage for 80 percent of the property’s cost and a second mortgage, at a higher rate, for most of the rest. At this writing, piggybacks aren’t available anymore, because they ramped up the lenders’ risk. If they return, you’ll need to compare the cost of both options. Piggybacks might be less expensive if you’ll pay off the second mortgage fast. In other cases, mortgage insurance could be the better choice.

10. Get a low-down-payment mortgage insured by the Federal Housing Administration. You can put down as little as 3.5 percent of the market price. At this writing, FHA insurance costs 1.5 percent at closing, which can be borrowed from the lender and repaid over the mortgage term. There’s also a premium tacked onto every monthly payment: 0.25 percent for loans of up to 15 years and 0.5 percent for longer loans. On loans that closed after January 1, 2001, your insurance is automatically canceled when your equity reaches 22 percent, as long as you have made payments for at least five years.

FHA loans are offered chiefly by mortgage banks, including online lenders, but they’re also available at some commercial banks and S&Ls. If a lender’s Web site offers loans with “little or no money down,” they’re almost certainly FHA loans or loans guaranteed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (see below).

For other leads to FHA lenders, go to www.hud.gov, click on “Search,” and then on “Lenders.” Borrowing limits are usually set county by county and cover homes that are modestly priced. They were raised sharply in 2008, to help homeowners refinance during the mortgage crisis. At this writing, here are the maximum loans for single-family homes: $271,050 in lower-cost areas up to $625,500 in very-high-cost areas. The limits may change, either up or down. For the latest, see the FHA’s Web site www.fhaoutreach.gov or check the Yellow Pages for a HUD-certified real estate agent in your area. For the loan limit in your area, go to MortgageLoanPlace at www.mortgageloanplace.com. For home buying and mortgage advice, call HUD’s Housing Counseling Hotline (800-569-4287) for a counselor in your area or visit www.hud.gov/fha.

11. Get a mortgage sponsored by a housing finance corporation such as Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Corporation) or Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation). Down payments run as low as 3 or 5 percent. To find a Fannie lender, go to the Fannie Mae Web site (www.fannie Mae.com), click on its site map, and scroll down to “Find a Lender Search,” or call 800-7-FANNIE (800-732-6643). Fannie also backs no-down-payment loans offered to rural residents of modest means through USDA Rural Development (formerly the Farmers Home Administration).

12. Get a no-down-payment loan guaranteed by the Department of Veterans Affairs. You can usually borrow as much as the house is appraised for, up to a certain limit—$417,000 in 2009 (this number rises annually; limits are higher in certain high-cost counties as well as Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). For county-by-county limits, go to the Web site of VALoans.com (www.valoans.com).

The up-front fee for a no-down-payment VA loan is 2.15 percent for regular military and 2.4 percent for Reserves and the National Guard. For regular military, that drops to 1.5 percent if you can afford a down payment of 5 percent or more and 1.25 percent if you can put 10 percent down. For Reserves it drops to 1.75 percent and for the Guard to 1.5 percent. This fee needn’t be paid in cash; you can include it in the loan. For more information and a list of VA-approved lenders, go to www.homeloans.va.gov.

VA loans are generally made through mortgage banks, including online lenders, although S&Ls, commercial banks, and credit unions may offer them too. Generally speaking, you qualify if you’re a veteran, on active duty, and have served at least two years, or, under certain conditions, are an unmarried surviving spouse. At this writing, VA loans also go to people who have done six years in the Selected Reserve, including the National Guard. Reservists pay an extra 0.25 percent up front. For details, check www.homeloans.va.gov or call your regional VA office.

13. Sell any stocks or mutual funds you own that aren’t part of your tax-deferred retirement plan. Put the proceeds into your down payment.

14. Borrow part of the down payment from your employee retirement savings account, if the plan allows it. For details, see page 313. The interest you pay on the loan goes back into your account.

15. Borrow part of the payment from your bank. Take a loan against the credit line on your bank credit card or write a check against your overdraft checking. This choice should be desperation only, to wrap up a deal. You’ll want to repay this high-interest loan as fast as you can.

16. Buy a house in a foreclosure sale or through a real estate agent who handles foreclosures. There are no big bargains. But you might buy for 5 or 10 percent less than the price of a similar home that wasn’t foreclosed (page 575).

17. Check the cost of buying from a builder in a new development. Builders often sell on flexible terms. One example: a buydown. The builder might pay the lender $5,000 or so to reduce your mortgage payments for one to three years. That will help you qualify for the loan. Alternatively, the lender may offer to cover the first two mortgage payments or pay closing costs and fees in return for charging you a higher interest rate.

Don’t waltz into this deal without asking how much it’s going to cost. You may have to pay list price on the house rather than bargaining it down. You may have to use the builder’s mortgage affiliate, who won’t come cheap. And what will the mortgage cost you once the buydown period passes? Always compare the builder’s offer—rates, fees, costs, points—with what you could get from a Web lender or other outside sources. If you get a better offer, the builder may sweeten his or her deal too.

18. Shop. Interest rates and fees vary more widely than you realize, especially in tight markets. You might find a lender that charges 1 percentage point less on a fixed-rate loan and more than that on an adjustable loan. Smaller, local banks are offering good deals. Here are the top sites for comparison shopping online: the major banking institutions—Bank of America, CitiMortgage, Chase Home Mortgage, and Wells Fargo—and Internet lenders (page 570) that meet the pricing transparency standards of Jack Guttentag, professor of finance emeritus at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania (www.mtgprofessor.com).

19. Lease with an option to buy. This approach faded during the years when anyone with a pulse could get a mortgage loan. It’s now coming back because buyers with shaky credit can’t borrow and sellers are having trouble getting their price.

With an option, you pay a nonrefundable fee (perhaps $3,000 to $5,000) for the right to buy the house in one to three years at a stated price. You move in as a tenant, paying more than the normal rent. The fee plus the extra rent is credited toward a down payment. When it comes time to buy, you get your own mortgage for the remaining money owed. To find one of these deals, ask a real estate agent, look for lease-option ads in the newspaper or online, or check the classifieds under “Rentals.” People renting out houses would sometimes rather sell. Don’t sign a lease option without having a lawyer go over it to be sure it’s fair. Sometimes it’s not.

Do a lease option only if you’re sure that you can get a sufficient mortgage when the option comes due. That means prequalifying yourself with a lender (page 560). The lease option should be viewed solely as a way of accumulating a down payment. If you can’t get a mortgage when the time comes to buy, your option will expire, and you’ll lose the extra money you paid. (You might recover something, however, if the option price is less than the house’s fair market value. Before the option expires, advertise it for sale. An investor might respond.)

Why Your Credit Score Matters

The mortgage interest rate you’re offered will depend on your credit score (page 265). For the best rate, you have to score above 740. A 700 score is almost as good. As your score drops, rates and fees go up, and the amount you’re allowed to borrow goes down. Below 660, rates rise a lot, and you’re offered fewer types of loans. Below 620, you’re “subprime” and may not be able to borrow at all. Your lender will check your credit score as part of your mortgage application and mail you the result. To qualify for a better mortgage, get the debt on your credit cards down to less than half your total credit lines, take out no new cards, and pay your bills on time, every time. Subprime borrowers might still be accepted by the FHA or VA.

When couples with different FICO scores apply for a mortgage, the lender uses a middle range. If one of you is subprime, however, you’ll be stuck with a higher interest rate. Consider applying in the name of the person with the better score, if his or her earnings will support the loan.

How Large a Mortgage Can You Get?

How much you can borrow depends on both your credit score and the size of your current debt. Find yourself below, to see the maximum monthly mortgage payment that lenders typically think you can afford. That helps you target a price range for the houses you should be looking at. Just because you can borrow this much, however, doesn’t mean that you should. It’s important to keep your loan within your comfort zone.

If you have a high credit score, a solid income, and some investments, lenders usually allow you to spend up to 30 percent of your stable, monthly gross income on home-owning expenses (principal and interest on your mortgage debt, homeowners insurance, and incidentals such as condominium fees). Up to 45 percent of your income could be committed to total debt, including housing expenses, alimony, child support, and payments toward long-term consumer debt (defined as loans lasting for more than 10 months, including car loans or leases, installment debt, and credit card debt). If you’re self-employed, these ratios apply to your net income after expenses. If you depend on year-end bonuses, part of that bonus might be considered “stable” income.

If you have a high credit score, a solid income, and some investments, lenders usually allow you to spend up to 30 percent of your stable, monthly gross income on home-owning expenses (principal and interest on your mortgage debt, homeowners insurance, and incidentals such as condominium fees). Up to 45 percent of your income could be committed to total debt, including housing expenses, alimony, child support, and payments toward long-term consumer debt (defined as loans lasting for more than 10 months, including car loans or leases, installment debt, and credit card debt). If you’re self-employed, these ratios apply to your net income after expenses. If you depend on year-end bonuses, part of that bonus might be considered “stable” income.

If you have an average credit score, with an acceptable credit history and sufficient income, lenders may want you to spend no more than 25 percent of your income on basic housing expenses, with a maximum of 33 to 40 percent on total debt.

If you have an average credit score, with an acceptable credit history and sufficient income, lenders may want you to spend no more than 25 percent of your income on basic housing expenses, with a maximum of 33 to 40 percent on total debt.

If you’re applying for a special lower-income loan, you’re allowed up to 30 percent of your monthly income for housing expenses and 35 percent for total debt. Ratios can be higher on loans insured by the Veterans Administration or the affordable housing loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration.

If you’re applying for a special lower-income loan, you’re allowed up to 30 percent of your monthly income for housing expenses and 35 percent for total debt. Ratios can be higher on loans insured by the Veterans Administration or the affordable housing loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration.

Sometimes lenders are willing to exceed these percentages, but they’re doing you no favor. Bigger loans let you buy a better house but also require monthly payments higher than you can really afford. Larger homes cost more to heat, light, and repair. If you move to a pricier neighborhood, you may feel the need to own a fancier car or throw expensive birthday parties for your kids. Consider all the costs before choosing a house that requires you to borrow more than the guideline amount.

Sometimes lenders are willing to exceed these percentages, but they’re doing you no favor. Bigger loans let you buy a better house but also require monthly payments higher than you can really afford. Larger homes cost more to heat, light, and repair. If you move to a pricier neighborhood, you may feel the need to own a fancier car or throw expensive birthday parties for your kids. Consider all the costs before choosing a house that requires you to borrow more than the guideline amount.

Most lenders no longer offer “stated-income” or “stated-asset” loans— otherwise known as “liar’s loans.” With these loans, you merely stated your income or assets and the lenders didn’t check. They simply charged a higher interest rate to cover the loan’s expected risk. Not surprisingly, a high percentage of them defaulted. Now you usually have to provide full documentation to get a mortgage loan. That not only protects the lender, it protects you from borrowing more than you can reasonably pay. In some cases, however, a self-employed person with good credit and a sizable downpayment might still be able to borrow on a stated-income basis.

Most lenders no longer offer “stated-income” or “stated-asset” loans— otherwise known as “liar’s loans.” With these loans, you merely stated your income or assets and the lenders didn’t check. They simply charged a higher interest rate to cover the loan’s expected risk. Not surprisingly, a high percentage of them defaulted. Now you usually have to provide full documentation to get a mortgage loan. That not only protects the lender, it protects you from borrowing more than you can reasonably pay. In some cases, however, a self-employed person with good credit and a sizable downpayment might still be able to borrow on a stated-income basis.

If you want to know whether you can borrow enough to buy a particular house, ask to be preapproved for a mortgage loan. To win preapproval, you fill in an application and have your credit checked. The bank may also verify your income and assets. If you pass, you’ll get a letter telling you the maximum you can borrow at current interest rates (assuming no change in your financial condition). This helps you target a price range for shopping and gives you an edge over other bidders who haven’t yet been approved for a loan. You can get preapprovals from many lenders free on the Web, through a mortgage broker, or from a local lender directly. Some lenders charge for preapprovals and refund the cost if you go through with the loan. But why pay if you don’t have to?

If you want to know whether you can borrow enough to buy a particular house, ask to be preapproved for a mortgage loan. To win preapproval, you fill in an application and have your credit checked. The bank may also verify your income and assets. If you pass, you’ll get a letter telling you the maximum you can borrow at current interest rates (assuming no change in your financial condition). This helps you target a price range for shopping and gives you an edge over other bidders who haven’t yet been approved for a loan. You can get preapprovals from many lenders free on the Web, through a mortgage broker, or from a local lender directly. Some lenders charge for preapprovals and refund the cost if you go through with the loan. But why pay if you don’t have to?

You can also be prequalified. That’s a free estimate of how large a loan you might be able to get, based on your financial data but with no income verification or credit check. Using the Web, you could collect several estimates. Local lenders may prequalify you too, at no charge. Preapproval, however, is more exact.

If you’re checking out mortgages on Web sites, keep in mind that the monthly payments you see cover only principal and interest. You’ll also owe real estate taxes and premiums for homeowners insurance. Those expenses are usually bundled into the amount you pay the lender each month. The lenders hold them in escrow and make the tax and insurance payments for you.

If you’re checking out mortgages on Web sites, keep in mind that the monthly payments you see cover only principal and interest. You’ll also owe real estate taxes and premiums for homeowners insurance. Those expenses are usually bundled into the amount you pay the lender each month. The lenders hold them in escrow and make the tax and insurance payments for you.

If You Have a Choice, How Much Money Should You Put Down?

A larger down payment gives you a smaller loan and lower monthly payments. If you put down 20 percent or more, you’ll get a lower interest rate and better terms. Choose a large down payment if you want to hold down costs; if you’re determined to pay off the mortgage as fast as you can; if you have an irregular income and feel safer with lower monthly payments; or if you would otherwise fritter away your spare money. Higher down payments can yield handsome investment yields, thanks to your savings on interest costs and fees. To calculate this, go to the Mortgage Professor’s Web site (www.mtgprofessor.com), click on “Calculators” and scroll down to Calculator 12a.

A larger down payment gives you a smaller loan and lower monthly payments. If you put down 20 percent or more, you’ll get a lower interest rate and better terms. Choose a large down payment if you want to hold down costs; if you’re determined to pay off the mortgage as fast as you can; if you have an irregular income and feel safer with lower monthly payments; or if you would otherwise fritter away your spare money. Higher down payments can yield handsome investment yields, thanks to your savings on interest costs and fees. To calculate this, go to the Mortgage Professor’s Web site (www.mtgprofessor.com), click on “Calculators” and scroll down to Calculator 12a.

A smaller down payment sticks you with a larger loan, higher monthly payments, and a higher interest rate. Why do it if you have a choice? I can think of only two good reasons: (1) You want enough cash to fix up and furnish your new home. (2) You’ll use your extra cash to reduce a mound of credit card debt.

A smaller down payment sticks you with a larger loan, higher monthly payments, and a higher interest rate. Why do it if you have a choice? I can think of only two good reasons: (1) You want enough cash to fix up and furnish your new home. (2) You’ll use your extra cash to reduce a mound of credit card debt.

Should you choose a smaller down payment so that you can invest the rest of your money somewhere else? Not a good idea. The cost of this choice is far higher than people realize. That’s because lenders charge higher interest rates and fees to people who put less money down. To make up for that extra out-of-pocket cost, the cash return on your outside investment has to be surprisingly large—typically, equal to your higher mortgage rate plus about 5 percent. Say, for example, that you could have borrowed at 6 percent, but your lower down payment raised your rate to 6.25 percent (plus higher fees). To make up for those extra costs, your investment would have to earn about 11.25 percent, and that’s just to break even! You’d need an even higher return to make a profit.

Should you choose a smaller down payment so that you can invest the rest of your money somewhere else? Not a good idea. The cost of this choice is far higher than people realize. That’s because lenders charge higher interest rates and fees to people who put less money down. To make up for that extra out-of-pocket cost, the cash return on your outside investment has to be surprisingly large—typically, equal to your higher mortgage rate plus about 5 percent. Say, for example, that you could have borrowed at 6 percent, but your lower down payment raised your rate to 6.25 percent (plus higher fees). To make up for those extra costs, your investment would have to earn about 11.25 percent, and that’s just to break even! You’d need an even higher return to make a profit.

Skimping on your down payment almost never makes sense. An investment in your mortgage when you buy your house is one of the smartest ways that you can use your money.

Should you put zero down? Today, you can do this only with VA loans, or near zero with FHA loans and some loans backed by Fannie Mae. But you lose flexibility and may face higher costs. If interest rates fall, you won’t be able to refinance because you won’t have enough equity in your home. If you want to sell, you might not net enough to repay the mortgage, after subtracting 5 or 6 percent in sales commissions. Having equity in your home is one of your safety nets. Save for a down payment. It’s one of the best things you can do for yourself. If you buy with no money down, make higher monthly payments to build equity as fast as you can.

Should you put zero down? Today, you can do this only with VA loans, or near zero with FHA loans and some loans backed by Fannie Mae. But you lose flexibility and may face higher costs. If interest rates fall, you won’t be able to refinance because you won’t have enough equity in your home. If you want to sell, you might not net enough to repay the mortgage, after subtracting 5 or 6 percent in sales commissions. Having equity in your home is one of your safety nets. Save for a down payment. It’s one of the best things you can do for yourself. If you buy with no money down, make higher monthly payments to build equity as fast as you can.

Special Warnings to Subprime Borrowers

If your credit score is poor, you’re classed as a subprime borrower. That costs you a higher interest rate, if you can borrow at all. After the housing bubble burst, most lenders stopped giving subprime loans. But they’ll eventually come back. If you’re offered such a loan, here’s what to watch for:

Are you really a subprime credit? Some mortgage brokers steer clients to subprime loans when they could have qualified for something better. The brokers earn higher commissions on subprimes. Before accepting a subprime verdict, consider visiting a bank directly or applying for a loan on the Web (page 572). You might get a better deal.

Are you really a subprime credit? Some mortgage brokers steer clients to subprime loans when they could have qualified for something better. The brokers earn higher commissions on subprimes. Before accepting a subprime verdict, consider visiting a bank directly or applying for a loan on the Web (page 572). You might get a better deal.

Even if you start as a subprime borrower, you don’t have to stay in that category. Make your interest and principal payments on time for two or three years, then see if you can refinance into a higher-quality loan.

Even if you start as a subprime borrower, you don’t have to stay in that category. Make your interest and principal payments on time for two or three years, then see if you can refinance into a higher-quality loan.

Subprime loans normally carry prepayment penalties. You’ll owe a fee if you refinance within the first three years or so. So be sure that you’ll be able to carry your mortgage for at least that period of time.

Subprime loans normally carry prepayment penalties. You’ll owe a fee if you refinance within the first three years or so. So be sure that you’ll be able to carry your mortgage for at least that period of time.

Beware of rising interest rates. Before saying yes to this mortgage, ask the broker to show you any built-in rate increases over the next five years and what the monthly payments would be. How much more would you pay if rates in general rose by 1 or 2 percent? If you can’t afford to pay more each month, you might default and lose the house.

Beware of rising interest rates. Before saying yes to this mortgage, ask the broker to show you any built-in rate increases over the next five years and what the monthly payments would be. How much more would you pay if rates in general rose by 1 or 2 percent? If you can’t afford to pay more each month, you might default and lose the house.

A Technical Phrase You Can’t Ignore: Negative Amortization

Negative “am,” as it’s called for short, is a high-tech, death-defying, money-eating system for owing more money every time you make a monthly mortgage payment. Amortization is the payment schedule by which you reduce a loan to zero over a fixed number of years. Negative amortization means that instead of going down, the amount of your loan goes up.

You run into negative am whenever your monthly payments aren’t large enough to cover all the interest due. As an example, say that you’re paying $1,000 a month on a floating-rate mortgage whose rate goes up. You now owe an extra $50 in interest, but your mortgage contract lets you keep paying only $1,000. The missing $50 is added to your loan principal, so now you owe more than you did last month. Your interest cost rises too, because of the larger loan. The lender will let your debt increase by a certain amount. After that, you’ll be required to make much higher monthly payments on a schedule that will reduce the loan to zero.

The mortgages known as option ARMs (page 564) often mire you in negative am. So will any other mortgage whose payments stay level while the interest rate is allowed to float. At this writing, these dangerous mortgages aren’t being offered anymore, but plenty of old ones are still outstanding. If you find yourself with negative am, raise your monthly payments to climb out of it.

Finding the Right Mortgage

There are dozens of choices on the mortgage menu, all with different rates, different terms, and different fees. Here’s how to decide what’s best for you.

Traditional Adjustable-Rate Mortgages (ARMs)

With traditional ARMs, the interest rate and monthly payment change periodically—up or down—in line with the general level of rates. So far, they’ve proven to be low cost. An ARM with an annual adjustment might start at 1.5 or 2 percentage points under the cost of a fixed-rate loan—a valuable saving. Even if interest rates rise, the ARM will probably cost you less over the next three or four years. An ARM would cost more than fixed-rate loans if rates rose and didn’t fall, but rate rises rarely last longer than a couple of years. Over a full interest rate cycle, ARMs could easily cost the least. Among their advantages: you don’t have to pay fees for refinancing when interest rates fall, because ARM rates fall automatically. (For the specific questions to ask about ARMs, see page 565).

When to get a traditional ARM: (1) You need the lower monthly payment in the first year to buy the house you want. (2) You’ve looked at how payments might rise in the future and can handle them when they come. (3) You won’t panic when payments rise, because you have faith that they’ll fall again. (4) You expect to own the house for only four or five years (short-term owners should go for the cheapest ARM they can find). (5) You have plenty of money or plenty of confidence that your income will rise.

Fixed-Rate Mortgages

With these mortgages, you’re safe. Your monthly payments are fixed for as long as you hold the loan. If rates rise and stay high, you’ve got a terrific deal. If they fall, you can refinance at the lower rate (page 580). Fixed-rate mortgages make the most economic sense when they’re priced within one percentage point of an ARM’s regular interest rate (not the discounted “teaser” rate given during the ARM’s first year or so).

When to get a fixed-rate loan: (1) The size of the payment doesn’t stop you from getting the house you want. (2) You want to lock in your mortgage payments because you can’t count on earning a higher income in the years ahead. (3) You couldn’t afford your house if your mortgage payment rose. (4) The thought of rising mortgage payments scares you stiff. (5) You think current mortgage rates are unusually low. (6) You’re near retirement, at which point your income will drop.

Hybrid Mortgages

These are great loans for borrowers who want to start with guaranteed monthly payments but can’t quite afford the initial cost of a regular fixed-rate loan. With hybrids, you get a fixed rate for a specified period, often 3, 5, 7, or 10 years. Then the loan converts to an adjustable rate. You pay more per month than for a traditional ARM but less than for a straight fixed-rate loan. The longer the fixed-rate period, the higher your initial interest rate will be. Lenders refer to hybrids in shorthand. A loan labeled “5/1” gives you a fixed rate for five years, then switches to a variable rate that changes every year. A “7/1” loan fixes your rate for the first seven years. The first time the loan adjusts, the rate could jump by as much as 5 percentage points. Make sure that you understand the range of future possible rates before you sign. Also make sure your deal is guaranteed. Some hybrids let the lender change the terms if interest rates suddenly shoot up.

When to choose a hybrid loan: (1) You’ll stay in the house for only a few years. In effect, you have a fixed-rate loan at a lower monthly cost. (2) You hope mortgage rates will fall, at which point you’ll refinance. In the meantime, you want a mortgage payment that’s guaranteed. If rates don’t fall, you can still handle the payments. (3) You expect to be earning more money when the fixed term ends, so switching to a traditional ARM won’t bother you.

Interest-Only (IO) Mortgages

For the first few years of an IO mortgage, you pay only the interest on your loan and nothing toward principal. You get lower monthly payments, but you’re not reducing the debt. After 3 to 10 years (you choose), your payments jump to a level high enough to retire the loan over its remaining term. For example, say that you take a 30-year loan and pay nothing toward principal for the first five years. In the sixth year, you have to start paying enough to retire the loan over the remaining 25 years. That’s called recasting the loan, and your monthly payment jumps—often by a lot.

IOs today are being written mainly on 30-year fixed-rate loans, at a much higher interest rate than you’d pay for a traditional loan. When IOs are written on adjustable loans, they also cost more than you’d pay for a regular ARM.

When to choose an IO loan: Hardly ever. You’re looking at it only because you need a superlow monthly payment to qualify for the mortgage you want. That usually means you’re buying a house you really can’t afford. You’re gambling that you can handle the basic loan (which will be a large one, relative to your income) and make sharply higher monthly payments when the time rolls around. IOs always cost more in interest, whether you hold them for 5 years or 30 years, because of the higher rate and because the loan principal stays high.

Mortgages Called Option ARMs, FlexPay ARMs, or Pick-a-Pay

Mercifully, these terrible loans are now off the market. But plenty of old ones are still around. They allow you to choose how much you want to pay each month, including a payment so small that it doesn’t even cover the interest owed. That unpaid interest is added to your loan, so your debt goes up every month instead of down. Five years from the day you took this loan (and sometimes earlier), your options will run out. You’ll have to start paying enough to retire the mortgage over its remaining term. You won’t even be able to refinance if the value of your house is down. Anyone stuck with an option ARM should start paying enough every month to cover both interest and principal. Otherwise, you might be greasing a path to default.

Balloons

Balloon mortgages offer low, fixed payments for a specified period of time. After that, the entire loan falls due. First-mortgage balloons typically run for five to seven years. After that, the bank will usually refinance them at whatever rate is current at the time. You’ll pay a higher rate, however, if your credit score has dropped or you’ve fallen behind on some payments. You won’t be refinanced if your house is worth less than the amount of the loan. Before you borrow, be clear about your options at the end of the term and what fees and interest rates you might have to pay.

If you buy a house and give the seller a note for part of the payment due, that’s a balloon. When it falls due, the seller will rarely extend the term. If you don’t have the cash, you’ll be expected to borrow the money somewhere else.

When to consider a balloon: (1) The seller offers this loan to help you meet his or her price and you’re sure you can pay when the term is up. (2) The bank offers a balloon with very low payments—say, only the interest—for a fixed number of years. You expect to sell the house and repay the whole loan sometime before the balloon falls due. This assumes that the market value of your house will not decline. (3) If you don’t sell, you’re sure that the bank will let you refinance. But who can ever be truly sure? A balloon is a hazardous undertaking at any time.

All About ARMs

Take this checklist with you when you talk to the lender. Use it for hybrid mortgages too, because they’ll eventually turn into ARMs.

What’s the initial interest rate? ARMs usually offer bargain starter rates called teasers. Typically, they’re one or two points under the loan’s regular rate. Some teasers last for only 1 month; others, for 6 to 12 months. Some (on hybrid loans) last up to 10 years. Every time your rate adjusts, it will rise toward the regular, nondiscounted rate (although the rise can’t exceed a specified cap). During this short period, your interest rate can rise even if rates in general are coming down. Once you’ve reached the end of your teaser period, your payment will rise and fall in line with general market interest rates.

What’s the initial interest rate? ARMs usually offer bargain starter rates called teasers. Typically, they’re one or two points under the loan’s regular rate. Some teasers last for only 1 month; others, for 6 to 12 months. Some (on hybrid loans) last up to 10 years. Every time your rate adjusts, it will rise toward the regular, nondiscounted rate (although the rise can’t exceed a specified cap). During this short period, your interest rate can rise even if rates in general are coming down. Once you’ve reached the end of your teaser period, your payment will rise and fall in line with general market interest rates.

What interest rate is my loan linked to? Most mortgages today are tied to Treasury securities. Six-month ARMs rise and fall with six-month Treasury bills; one-year ARMs link to one-year Treasury bills. Over a whole interest rate cycle, a mortgage linked to short-term Treasuries should cost less and is the easiest to follow in the newspapers.

What interest rate is my loan linked to? Most mortgages today are tied to Treasury securities. Six-month ARMs rise and fall with six-month Treasury bills; one-year ARMs link to one-year Treasury bills. Over a whole interest rate cycle, a mortgage linked to short-term Treasuries should cost less and is the easiest to follow in the newspapers.

Other loans adjust twice a year in line with the London InterBank Offer Rate (LIBOR), which reflects Eurodollar borrowing rates. It tends to rise and fall more rapidly than Treasury rates do. In the West, mortgage rates might follow the cost-of-funds index (COFI) for savings and loan associations in the Federal Home Loan Bank Board’s 11th District, which covers California, Arizona, and Nevada. The COFI changes slowly, so your payments don’t rise or fall a lot, even if they’re adjusted once a year. But the sluggishness of the cost-of-funds index means that it may still be going up when rates in general have turned down, and vice versa. Finally, there’s also a cost-of-deposits index (CODI) that follows the interest rates that banks pay on three-month certificates of deposit. In practical terms, it doesn’t really matter which index your lender uses—you’ll have to take what you get.

What’s the margin? When figuring your ARM rate, the lender takes the index it uses and adds a fixed number of percentage points called a margin. This is one of the most important things that consumers should shop for. To see how it works, assume that your margin is 2.5 points. With the Treasury index at 3 percent, plus a 2.5 margin, your interest rate comes to 5.5 percent. If Treasuries rise to 4 percent, adding the margin raises your rate to 6.5 percent. Borrowers with good credit should get a low margin over the index (2.25 points is very good). Borrowers with poorer credit pay a higher margin (3 points or more). If you’re a good credit risk, be sure you get the low margin you deserve.

What’s the margin? When figuring your ARM rate, the lender takes the index it uses and adds a fixed number of percentage points called a margin. This is one of the most important things that consumers should shop for. To see how it works, assume that your margin is 2.5 points. With the Treasury index at 3 percent, plus a 2.5 margin, your interest rate comes to 5.5 percent. If Treasuries rise to 4 percent, adding the margin raises your rate to 6.5 percent. Borrowers with good credit should get a low margin over the index (2.25 points is very good). Borrowers with poorer credit pay a higher margin (3 points or more). If you’re a good credit risk, be sure you get the low margin you deserve.

The margin doesn’t matter during the months you have a discounted teaser rate (or the 3 to 10 years of fixed rates on a hybrid loan). It matters a lot, however, when your rate starts adjusting normally. Between two lenders linking their mortgages to the same or a similar index, the one with the smaller margin will cost you less (unless that lender blows it by charging higher fees).

How often will the interest rate change? Most traditional ARMs adjust your interest rate once a year. Some adjust every six months. Generally speaking, the more frequent the adjustment, the cheaper the mortgage over an entire interest rate cycle (including both rising and falling rates).

How often will the interest rate change? Most traditional ARMs adjust your interest rate once a year. Some adjust every six months. Generally speaking, the more frequent the adjustment, the cheaper the mortgage over an entire interest rate cycle (including both rising and falling rates).

What are the caps? You want fixed, annual limits on what you’ll have to pay in case interest rates go leaping up. If you took a teaser rate, your first adjustment cap is typically large—maybe as much as 5 percentage points. After that, the periodic cap dictates how much the lenders can add each year—typically up to 2 percentage points, no matter what happens to the underlying index. For example, say that market rates rise by 3 percentage points in the second year and stay there. Your mortgage rate will rise only 2 points the second year, then 1 point the third year. Alternatively, if rates rise by three percentage points and then fall back, your mortgage rate will rise 2 points the second year and then stay level or fall the third year, depending on how far the index drops. Over the life of the loan, your rate can’t rise by more than 5 or 6 percentage points, usually measured from your low, initial teaser rate. Given two similar loans, choose the one with the lower caps.

What are the caps? You want fixed, annual limits on what you’ll have to pay in case interest rates go leaping up. If you took a teaser rate, your first adjustment cap is typically large—maybe as much as 5 percentage points. After that, the periodic cap dictates how much the lenders can add each year—typically up to 2 percentage points, no matter what happens to the underlying index. For example, say that market rates rise by 3 percentage points in the second year and stay there. Your mortgage rate will rise only 2 points the second year, then 1 point the third year. Alternatively, if rates rise by three percentage points and then fall back, your mortgage rate will rise 2 points the second year and then stay level or fall the third year, depending on how far the index drops. Over the life of the loan, your rate can’t rise by more than 5 or 6 percentage points, usually measured from your low, initial teaser rate. Given two similar loans, choose the one with the lower caps.

After the initial interest rate period expires, what will I pay? The lender should show you a range of possible future payments based on various changes in interest rates. Ask for an illustration of the worst case too. If you faint dead away, maybe you should look at fixed-rate loans instead.

After the initial interest rate period expires, what will I pay? The lender should show you a range of possible future payments based on various changes in interest rates. Ask for an illustration of the worst case too. If you faint dead away, maybe you should look at fixed-rate loans instead.

What happened in the past? Ask the lender to show you how a mortgage payment like yours would have fluctuated over the past 10 years, using real interest rates. If the payment gyrations of an ARM make you uncomfortable, consider a fixed-rate loan instead.

What happened in the past? Ask the lender to show you how a mortgage payment like yours would have fluctuated over the past 10 years, using real interest rates. If the payment gyrations of an ARM make you uncomfortable, consider a fixed-rate loan instead.

Is there a floor? Some loans limit how far your interest rate can fall. All things being equal, look for a loan without a floor.

Is there a floor? Some loans limit how far your interest rate can fall. All things being equal, look for a loan without a floor.

Is there a risk of negative amortization? Loans with negative am sometimes allow your monthly payments to slip below the total amount of interest due. The lender adds the unpaid interest to the loan balance, so your loan amount goes up instead of down. Not recommended. You’ll find plenty of ARMs without this catch.

Is there a risk of negative amortization? Loans with negative am sometimes allow your monthly payments to slip below the total amount of interest due. The lender adds the unpaid interest to the loan balance, so your loan amount goes up instead of down. Not recommended. You’ll find plenty of ARMs without this catch.

How often does your monthly payment change? You want it to change every time the loan’s interest rate does. Otherwise you run the risk of negative amortization.

How often does your monthly payment change? You want it to change every time the loan’s interest rate does. Otherwise you run the risk of negative amortization.

Can I convert? Some ARMs carry the right to switch to a fixed-rate mortgage after a certain number of years without paying closing costs all over again. Lenders charge for this in various ways. Some add an up-front fee. Some tack an eighth or a quarter of a point onto your initial interest rate or an extra half point or more to the interest rate on your future fixed-rate loan. With charges like these, nobody’s giving you a bargain. Since you can’t predict whether you’ll want to convert, this generally isn’t an option worth paying for.

Can I convert? Some ARMs carry the right to switch to a fixed-rate mortgage after a certain number of years without paying closing costs all over again. Lenders charge for this in various ways. Some add an up-front fee. Some tack an eighth or a quarter of a point onto your initial interest rate or an extra half point or more to the interest rate on your future fixed-rate loan. With charges like these, nobody’s giving you a bargain. Since you can’t predict whether you’ll want to convert, this generally isn’t an option worth paying for.

How can I check the rate? If I had one dollar for every mistake a lender made when it adjusted an ARM payment, I’d be an instant millionaire. The bank may pick the wrong index, loan balance, or adjustment date; it might round the rate up when it should have been rounded down; a new loan servicer might get your loan terms wrong; principal prepayments might not have been credited properly. Small errors compound into large ones over the years. When you take an ARM, ask when the rate will be adjusted, how it’s done, and how you can track the index that underlies your loan. Verify the rate whenever a change looks too big or too small or your payment rises when interest rates in general have been going down. Pay the most attention to older loans. Small errors grow into big ones over several years. Consumers can get refunds if they were overcharged on a paid-up loan.

How can I check the rate? If I had one dollar for every mistake a lender made when it adjusted an ARM payment, I’d be an instant millionaire. The bank may pick the wrong index, loan balance, or adjustment date; it might round the rate up when it should have been rounded down; a new loan servicer might get your loan terms wrong; principal prepayments might not have been credited properly. Small errors compound into large ones over the years. When you take an ARM, ask when the rate will be adjusted, how it’s done, and how you can track the index that underlies your loan. Verify the rate whenever a change looks too big or too small or your payment rises when interest rates in general have been going down. Pay the most attention to older loans. Small errors grow into big ones over several years. Consumers can get refunds if they were overcharged on a paid-up loan.

You can check your ARM rate free at HSH Associates Financial Publishers (www.hsh.com), a reliable provider of mortgage information. Click on the “ARM Check Kit” on the left-hand toolbar.

On Points

In mortgagespeak, one point is 1 percentage point of the loan amount. For example, on a $100,000 loan, one point equals $1,000—to be paid in cash or added to the loan amount. Adding the fee to the loan saves you money up front, but you’ll wind up paying two or three times that amount in interest costs.

There’s a trade-off between the discount points you pay and the mortgage interest rate you’re charged. The higher the points, the lower the rate, and vice versa. So what should you do: cut your interest rate by paying extra points or not? Here’s how to decide:

Pay zero or minimal points if you’ll be in the house for only a few years. The points would cost you more than the higher interest you’ll pay. Points also make no sense when interest rates are very low.

Pay zero or minimal points if you’ll be in the house for only a few years. The points would cost you more than the higher interest you’ll pay. Points also make no sense when interest rates are very low.

Pay extra points if you’ll hold the house for many years. A lower interest rate will save you money over the long run, especially when interest rates are high.

Pay extra points if you’ll hold the house for many years. A lower interest rate will save you money over the long run, especially when interest rates are high.

To compare the dollars and cents, Web calculators help. There are two ways of looking at the question: (1) Over 10 years, will you save more money by lowering your points or raising your down payment? Test this at www.dinkytown.net, the site of KJE Computer Solutions of Minneapolis. (2) How long will it take for the savings from lower interest payments to offset the cost of paying higher points? You can test this at www.mtgprofessor.com, or Choose to Save, at www.choosetosave.org.

To compare the dollars and cents, Web calculators help. There are two ways of looking at the question: (1) Over 10 years, will you save more money by lowering your points or raising your down payment? Test this at www.dinkytown.net, the site of KJE Computer Solutions of Minneapolis. (2) How long will it take for the savings from lower interest payments to offset the cost of paying higher points? You can test this at www.mtgprofessor.com, or Choose to Save, at www.choosetosave.org.

Short Term or Long?

A traditional mortgage runs for 30 years. Monthly payments are low, which is what younger buyers usually need. In the early years, most of that payment goes for interest, not principal. Over any holding period, 30-year loans cost more in interest than loans of shorter terms.

Among the middle-aged, buyers are choosing 15-year and even 10-year terms. Monthly payments are higher, but these loans build equity faster and minimize interest costs. They’re a way of ensuring that you’ll own your home free and clear by the time you retire.

The new 40-year mortgages offer especially low payments to the cash poor. They’re more predictable than interest-only loans. You won’t face a sudden jump in payments five years from now, as IO borrowers will. The downside (and it’s a big one): You pay a high interest rate. When you sell, you’ll have paid much more interest and built less equity than with a 30-year loan. I’d stay away.

How to Shorten the Term of Your Current Loan

Anytime you want, send in a larger monthly check than the amount that is actually due. The extra money will automatically go toward reducing your loan. Many lenders even have a spot on the monthly bill where you can note extra principal payments. Others suggest that you send a note with every larger check, so the bank will know there’s no mistake. A disciplined way of prepaying is to add money every month. Alternatively, send a larger check whenever you can. Every dollar counts.

With a fixed-rate mortgage, your prepayments shorten the term of the loan. If you have an adjustable-rate mortgage, however, the bank may keep the term the same and lower the monthly payment you owe. To accelerate that mortgage, keep on paying the same monthly amount that you did before.

Note that making prepayments doesn’t give you the right to skip a month. You still owe the basic monthly payment, no matter how far ahead of schedule you are.

For Maximum Flexibility, Take a 30-Year Loan and Repay It on a Faster Schedule

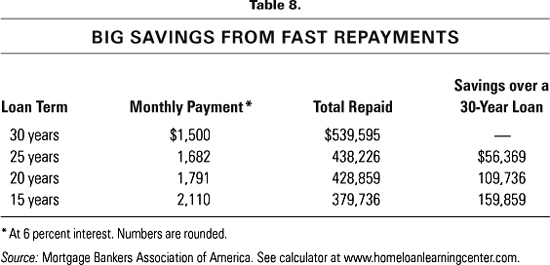

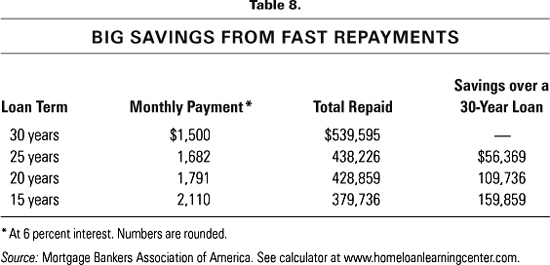

Take a 30-year loan. Then find out how large a monthly payment you’ll have to make to get rid of the loan over 15 or 20 years, and pay at that rate. To decide how much extra you want to spend, use the calculators at www.bankrate.com, www.choosetosave.org, www.dinkytown.net, or www.mtgprofessor.com. I guarantee that the savings will amaze you. If there’s a month when you’re squeezed for cash, you can always drop back to the minimum payment the loan requires. Be sure that you get a loan without a prepayment penalty. The table on page 570 shows how much money shorter terms can save you on a $250,000 loan.

Is It Worth Your While to Pay Off Your Mortgage Faster?

Usually, yes. Faster payments will:

Force you to save. Otherwise that money might be frittered away.

Force you to save. Otherwise that money might be frittered away.

Reduce the amount of interest you pay over any period of time that you hold the loan.

Reduce the amount of interest you pay over any period of time that you hold the loan.

Give you an attractive risk-free return on your money. Prepaying a loan is an investment. The return on your investment equals your mortgage rate. As an example, prepayments on a 6.5 percent mortgage give you a 6.5 percent investment return, guaranteed. That’s a better deal than you’d get from other safe, taxable investments, such as a bank or money market savings account.

Give you an attractive risk-free return on your money. Prepaying a loan is an investment. The return on your investment equals your mortgage rate. As an example, prepayments on a 6.5 percent mortgage give you a 6.5 percent investment return, guaranteed. That’s a better deal than you’d get from other safe, taxable investments, such as a bank or money market savings account.

Build your home equity faster. That’s especially important in a weak housing market, where rising prices aren’t building equity for you.

Build your home equity faster. That’s especially important in a weak housing market, where rising prices aren’t building equity for you.

Put you in a better position to trade up to a larger house. When you sell, you’ll have more money in hand to put toward your next down payment.

Put you in a better position to trade up to a larger house. When you sell, you’ll have more money in hand to put toward your next down payment.

Ensure that you’re mortgage free by the time you retire.

Ensure that you’re mortgage free by the time you retire.

Lower your cost of living, if you inherit a bucket of money and put it toward reducing or eliminating your loan.

Lower your cost of living, if you inherit a bucket of money and put it toward reducing or eliminating your loan.

Get you a lower interest rate. The rate on a 15-year loan may be a quarter or half point less than the rate on a 30-year loan.

Get you a lower interest rate. The rate on a 15-year loan may be a quarter or half point less than the rate on a 30-year loan.

Save you a small fortune in interest payments.

Save you a small fortune in interest payments.

It does not make sense to quick-pay your mortgage if:

You’re carrying credit card debt that’s costing you 12 to 28 percent or more. By paying it off, you get a 12 to 28 percent return on your money. First get rid of consumer debt. Then accelerate mortgage payments, starting with any home equity debt.

You’re carrying credit card debt that’s costing you 12 to 28 percent or more. By paying it off, you get a 12 to 28 percent return on your money. First get rid of consumer debt. Then accelerate mortgage payments, starting with any home equity debt.

You aren’t investing enough for your retirement. Maximize your 401(k), 403(b), IRA, or Roth IRA account before tackling your mortgage debt.

You aren’t investing enough for your retirement. Maximize your 401(k), 403(b), IRA, or Roth IRA account before tackling your mortgage debt.

You don’t have an emergency savings account. Build this cushion fund first (page 213).

You don’t have an emergency savings account. Build this cushion fund first (page 213).

You have children and haven’t been saving enough to help them with the expenses of higher education. Start or add to your 529 investment (page 667).

You have children and haven’t been saving enough to help them with the expenses of higher education. Start or add to your 529 investment (page 667).

Once you’ve taken care of your retirement fund, emergency savings, and college savings, you’re ready to prepay your mortgage loan.

Once you’ve taken care of your retirement fund, emergency savings, and college savings, you’re ready to prepay your mortgage loan.

One way to quick-pay painlessly is through a biweekly payment schedule. Instead of making monthly payments, make half a monthly payment every two weeks. Result: one extra full payment per year, which shortens the term of a 30-year loan to about 23 years. Lenders sell quick-pay plans, charging you $195 to $350 or more for the paperwork. That’s a waste of money. Here’s Jane’s Free Biweekly Payment Plan: add 1/12th of a payment to your regular payment every month. You get the same result that you would with a useless commercial plan.

Another quick-payment scheme, called an offset mortgage, involves money transfers among accounts. Just watch the bouncing ball: (1) You open a home equity line of credit. (2) You borrow an amount equal to the size of your monthly payment from your home equity line and use it to reduce your mortgage balance. (3) You use your paycheck to repay the home equity line. (4) You pay your monthly bills by withdrawals from your home equity line. (5) All together, these transactions get money into your mortgage a little faster. If you spend your whole paycheck, you might save something in interest, depending on the home equity interest rate you pay. If you spend less than your total paycheck, your mortgage will shrink at a faster rate.

Naturally, this is sold as a package, for a price. It’s complex and confusing, and you can’t be sure how much you’re saving (if anything). Skip it, and simply add money to your mortgage payment every month.

You may think prepayments don’t matter because you expect to sell your house within just a few years. But they do. No matter when you sell, prepayments will lower your interest costs and increase your home equity.

Are you keeping your big mortgage because you “need” the tax deductions? Phooey. “Needing” deductions must be the most successful piece of financial propaganda that the industry has ever launched. Okay, you can tax-deduct mortgage interest. But your tax savings amount to only a fraction of the cost. You pay the rest right out of your pocket—money transferred from you to the bank.

For example, if you’re in the 25 percent bracket, the write-off saves you 25 cents out of every dollar you pay in interest. The remaining 75 cents is pure expense. If you had no mortgage (or a smaller mortgage), here’s what would happen to every dollar you didn’t pay in interest: 25 cents would go for federal income tax and 75 cents would be yours to keep. Getting rid of a loan is pure gain.

How to Find a Good Mortgage

It’s nuts not to shop. Some lenders charge lower interest rates and fees than others do. A percentage point saved on a 30-year, $200,000 loan is worth almost $64 a month.

Start with the Web. Check rates at sites such as Eloan (www.eloan.com), which provides offers from competing lenders. Also, check the lenders that make loans directly and meet the conditions for being a full-disclosure, Upfront Mortgage Lender (UML), as laid out by Jack Guttentag, the Mortgage Professor (for details, see www.mtgprofessor.com). UMLs disclose all costs—including rates, fees, and other terms—and let you price your individual mortgage online. They don’t necessarily have the lowest costs, but they’re visible and guaranteed. Note that UMLs don’t qualify you for loans, they only give you prices based on the information you supply. People with lower credit scores will have to pay higher rates. If you’re not approved for a conventional loan, reapply for a loan backed by the FHA.

Start with the Web. Check rates at sites such as Eloan (www.eloan.com), which provides offers from competing lenders. Also, check the lenders that make loans directly and meet the conditions for being a full-disclosure, Upfront Mortgage Lender (UML), as laid out by Jack Guttentag, the Mortgage Professor (for details, see www.mtgprofessor.com). UMLs disclose all costs—including rates, fees, and other terms—and let you price your individual mortgage online. They don’t necessarily have the lowest costs, but they’re visible and guaranteed. Note that UMLs don’t qualify you for loans, they only give you prices based on the information you supply. People with lower credit scores will have to pay higher rates. If you’re not approved for a conventional loan, reapply for a loan backed by the FHA.

For comparison, you’ll also find the largest mortgage banks online: Bank of America (www.bankofamerica.com); Chase Home Mortgage (www.mortgage.chase.com); CitiMortgage (www.citimortgage.com); and Wells Fargo (www.wellsfargo.com).

If you find a good rate on the Web, borrow there. E-lenders are fully equipped to handle their side of the paperwork by phone, e-mail, and local agents.

Ask a local bank, mortgage bank, savings and loan, or credit union. You might prefer the experience of talking with someone locally. Often, local banks offer lower interest rates and fees. Once the loan closes, however, the bank will probably sell it to an investor somewhere else in the United States (or the world), so some other institution will be servicing it for you.

Ask a local bank, mortgage bank, savings and loan, or credit union. You might prefer the experience of talking with someone locally. Often, local banks offer lower interest rates and fees. Once the loan closes, however, the bank will probably sell it to an investor somewhere else in the United States (or the world), so some other institution will be servicing it for you.

Ask a mortgage broker. Mortgage brokers know all the lenders and the offers. Their job is to shop the market and find you a suitable loan at the lowest possible rate. They can be especially helpful if you’re a first-time buyer, need an FHA or VA loan, have problem credit, or need other special services.

Ask a mortgage broker. Mortgage brokers know all the lenders and the offers. Their job is to shop the market and find you a suitable loan at the lowest possible rate. They can be especially helpful if you’re a first-time buyer, need an FHA or VA loan, have problem credit, or need other special services.

Getting a loan through a mortgage broker should cost exactly the same as you’d pay if you went to the lender yourself. Unfortunately, not all brokers play fair. Some of them overcharge in ways you don’t suspect. For example, they might: (1) steer you into a higher-rate loan because it pays them a higher commission, all the time telling you that it’s the best you can get; (2) quote you an extralow rate (even lower than you found on the Web) to get your business, then tell you (falsely) “the market has changed” and deliver a higher rate; (3) say they’re charging you “one point” (1 percent of the loan) without disclosing that the lender pays them a second point, which is included in your mortgage rate; (4) claim “Our services are free,” then put you into a high-rate loan that pays them an extra-high commission. No services are free. A study for the Department of Housing and Urban Development, published in 2008, found that borrowers pay an average of $300 to $450 more in fees when they work with a mortgage broker than when they borrow directly from the lender. At this writing, some lenders won’t deal with brokers because so many of them brought in deceptive loans during the housing boom.

To be sure you’re dealing with an honest broker, start by negotiating a fee. Then ask to see—actually see—the sheet that shows the wholesale interest rate and points the lender charges. The sheet might say “6 + 1,” meaning 6 percent plus one point. You should pay that amount plus the broker’s fee, and no more. The broker should put the fee in writing and agree not to add a percentage to any third-party charge, such as the appraisal.

Consider doing business with one of the people who call themselves an Upfront Mortgage Broker. They promise to find you the best wholesale rate you qualify for and to disclose all their fees. You’ll find them listed at the Upfront Mortgage Brokers Association site (www.upfrontmortgagebrokers.org). If none is local, you can deal with some of them by phone or online. For other mortgage brokers, check the National Association of Mortgage Brokers (www.namb.org), the Web, the Yellow Pages, real estate brokers (some of whom have mortgage broker affiliates), and friends. Ask these brokers to follow the same fee-disclosure procedures that Upfront Mortgage Brokers do. If they won’t, don’t work with them.

Regardless of the type of broker you use, keep careful notes of your conversations, including the interest rate the broker says you’ll get. Make a list of features you want in the loan, such as no prepayment penalty. Go down your checklist before agreeing to the loan. Any broker, including the Upfronters, can pull a fast one.

By the way, mortgage lending officers at the big banks can deceive you, too. They might put you into a more expensive loan when you could have qualified for something cheaper. That’s why it’s so important to comparison shop.

Ask your real estate agent. He or she may know of a local lender with good deals. But back off if the real estate firm has an affiliated mortgage company. Your agent might pressure you to pop over to the next desk and apply for a loan. Don’t sign anything until you’ve shopped around to find out what rates and fees are normal for someone in your situation. The mortgage you’re being pushed toward might be high priced.

Ask your real estate agent. He or she may know of a local lender with good deals. But back off if the real estate firm has an affiliated mortgage company. Your agent might pressure you to pop over to the next desk and apply for a loan. Don’t sign anything until you’ve shopped around to find out what rates and fees are normal for someone in your situation. The mortgage you’re being pushed toward might be high priced.

Apply through several sources—a bank, a mortgage broker, a Web lender—to see what you can get. Shop, shop, shop! Multiple mortgage applications normally show on your credit history and pull down your credit score. But all applications made within a single 14-day period count as a single application, so you’re okay.

Apply through several sources—a bank, a mortgage broker, a Web lender—to see what you can get. Shop, shop, shop! Multiple mortgage applications normally show on your credit history and pull down your credit score. But all applications made within a single 14-day period count as a single application, so you’re okay.

Don’t answer spam ads for low-rate mortgages—they aren’t from real lenders. At best, the spammers are collecting personal information to sell to middlemen who, in turn, will sell it to real lenders, who may want to offer you a loan. At worst, they’ll use your information in some identity-theft scam.

Don’t answer spam ads for low-rate mortgages—they aren’t from real lenders. At best, the spammers are collecting personal information to sell to middlemen who, in turn, will sell it to real lenders, who may want to offer you a loan. At worst, they’ll use your information in some identity-theft scam.

Don’t Get Soaked by Fees

Some lenders go crazy with fees and mortgage-closing costs because they know that consumers usually don’t compare. Fees vary widely. The same $200,000 loan could cost anywhere from $2,000 to $10,000, depending on where you borrow. So shop for fees as well as rates. You want to be sure that an apparently low-rate loan doesn’t come larded with extra costs. A typical list includes application fees, points, “origination fee” (that’s an additional percentage point for making the loan), underwriting, document preparation, escrow, recording, wire transfer, lender inspection, appraisal, title insurance, payments to the mortgage broker, payments to the bank’s lawyer, rate lock (the cost of guaranteeing your rate for a certain period of time), credit report, courier, “processing” (a shameless kitchen-sink fee), pizza, coffee, Gucci shoes (well, maybe not, but if they could … ).

Lenders have to give you a “good-faith estimate” of their fees within three days of receiving your loan application. But an estimate isn’t a guarantee. At the closing itself (or only 24 hours before), you might discover that fees have miraculously risen. At that point, all you can do is walk away or pay.

Some Web lenders bundle their fees into a single charge and guarantee it—a welcome development. Whenever consumers are able to make comparisons, fees soon decline. You’ll also find some lenders who advertise that they have “no closing costs”; they’ve bundled those costs into the mortgage itself. I wish all lenders would do this, because it gives you just one number to compare—the interest rate—with nothing else to trip you up.

At the closing, you’ll have additional costs, such as local transaction taxes, prepaid interest if your mortgage closes before the end of the month, and the price of any oil or propane that the seller left in the tank. You’ll also owe impounds—your first monthly payments toward real estate taxes and homeowners insurance. Some lenders let you pay your taxes and insurance separately but may charge you for the privilege.

Random Mortgage Recommendations

Don’t sign an agreement to buy unless it includes a mortgage contingency clause. That makes your purchase contingent on finding a loan. If you can’t borrow enough money, the deal is off and you get your deposit back.

Don’t sign an agreement to buy unless it includes a mortgage contingency clause. That makes your purchase contingent on finding a loan. If you can’t borrow enough money, the deal is off and you get your deposit back.

To compare the cost of fixed-rate loans, look at the annual percentage rate (APR). The APR includes points and certain other financing charges, and is always higher than the stated lending rate. But it doesn’t include all your closing costs, so a loan that looks a tad cheaper could be a tad more expensive after everything is paid. To get the best deal, you still have to check the fees.

To compare the cost of fixed-rate loans, look at the annual percentage rate (APR). The APR includes points and certain other financing charges, and is always higher than the stated lending rate. But it doesn’t include all your closing costs, so a loan that looks a tad cheaper could be a tad more expensive after everything is paid. To get the best deal, you still have to check the fees.

On adjustable loans, the APRs last only until the first interest rate change. They’re useful for comparing two loans with adjustable rates but tell you nothing about what you’ll ultimately pay.

Here’s the minimum your lender will need when you apply for a standard loan:

Here’s the minimum your lender will need when you apply for a standard loan:

1. The purchase contract for the new house and the sales contract if you sold an old one.

2. Banking information: names and addresses of your banks, bank account numbers, copies of your latest statements.

3. Employment information: employer’s name and phone number, proof of earnings (pay stubs, W-2 forms), your two most recent tax returns.

4. If you’re self-employed, balance sheets for your business and three years of business and personal tax returns. It will take longer to process your loan, and you may be asked for a higher down payment.

5. Names and addresses of all creditors and the amounts you owe. (This will be checked against your credit report.)

6. Proof of what you currently pay for housing, either mortgage or rental payments.

7. Proof of other assets you own, such as mutual fund or brokerage house statements and retirement fund reports.

8. Proof of a cash reserve—enough for the down payment, closing costs, and the first two or three mortgage payments.

9. A certificate of eligibility if you’re applying for a VA loan.

10. A letter from the donor if you’re using a cash gift for the down payment. (The bank wants to be sure it’s not a loan.)

11. The mortgage application fee.

There will be more requests for financial data as the loan processor checks you out. In fact, it’s going to drive you crazy. But button your lip and supply the data. If the application seems stalled, keep calling to try to move it along.

When a lender drags its tail and a deadline looms, call the mortgage broker and ask about starting all over again. Some lenders can close loans fast, efficiently, and at no extra cost.

When a lender drags its tail and a deadline looms, call the mortgage broker and ask about starting all over again. Some lenders can close loans fast, efficiently, and at no extra cost.

The lender will have the property appraised. If the value turns out to be less than you agreed to pay, that’s your problem, not the bank’s. It will lend only on the appraised amount. You’ll have to come up with more cash than you’d planned or get the seller to accept a lower price.

The lender will have the property appraised. If the value turns out to be less than you agreed to pay, that’s your problem, not the bank’s. It will lend only on the appraised amount. You’ll have to come up with more cash than you’d planned or get the seller to accept a lower price.

Some loans carry prepayment penalties. They’re typically added to loans with especially low up-front fees or low interest rates that will soon rise. The penalties usually apply only during the loan’s first three to five years and only if you refinance (page 580) or prepay more than 20 percent of the loan balance in a single year; no penalties are levied on the prepayment strategies outlined on page 569. The upside of accepting a loan with a prepayment penalty is that you start with a lower monthly payment. The downside is that you effectively can’t refinance during the penalty period if interest rates decline.