Which Kinds of Investments Serve You Best?

When you start, the jigsaw puzzle that’s your

personal money lies in dozens of pieces, all jumbled up.

When you finish, the picture will be clear.

For investment success, you need a concept; a framework on which to hang all the thoughts and suggestions that are constantly coming your way. Should you buy this mutual fund or that one? How do you choose between stocks and bonds? Which risks make sense and which don’t?

There are logical answers to these questions, but only if you start with a sensible investment plan. Once you’ve drawn up that plan, the mysteries of money will become clearer. You’ll see exactly the kinds of investments you ought to make. Just as important, you’ll know which investments to avoid.

Your plan will not make you rich tomorrow. You’re not betting the farm on the pipe dream of doubling your money overnight. Instead you’re using your common sense to map a steady strategy for building wealth.

I would write a get-rich-quick book if I could. Everyone (me included) dreams of learning how to beat Wall Street in three easy lessons and with no risk. But the schemes behind such books are usually a ticket to the poorhouse.

There are no easy ways to beat Wall Street. That’s not even an intelligent goal. Thoughtful people buy the kinds of investments that will yield the combination of safety, income, and growth they need. At the end of the road, they will look back and see that they did well.

Everyone needs an investment policy. It’s a written plan for making good choices in the financial markets. Professional money managers always work within a policy framework and so should you. Once in place, it will end your uncertainties about where to put your money and how to react when the markets bounce around.

Preparing an investment policy isn’t complicated. In its simplest form, it’s an asset allocation plan. You decide what percentage of your money to hold in U.S. stocks, international stocks, short-term bonds, long-term bonds, and cash. You don’t make a wild guess or pick a sample allocation from a pie chart on the Web. You create a policy for yourself alone, based on what you’re saving the money for and how much risk it’s wise to take. This chapter will show you how to do it. As you work with the plan, you can make it more detailed—for example, deciding how much you want to put in emerging markets, within your international allocation.

An investment policy should always be written down. When the markets rise or fall substantially, you consult your policy and bring your investments back to their original allocation. You know that’s going to work for you, over the long term, because it reflects your personal needs and goals.

The first step toward better investing is learning what has worked in the past. These are the lessons that history teaches:

1. For building capital long term, buy stocks. You are taking only a modest risk. Over 15-year periods, stocks have almost always outperformed bonds and have left simple bank accounts in the dust. Sometimes stocks plunge, as you know all too well. But avoiding them isn’t the answer. The answer is owning them in the right proportion, as this chapter will explain.

2. Buy stock-owning mutual funds, not stocks themselves. Funds diversify your investments and balance your risks. Picking stocks individually is a hobby, not a productive investment strategy for amateurs. You can’t beat the market with a handful of individual stocks. If you try, you’ll almost certainly wind up with a smaller retirement fund. You can’t even trust “blue-chip” stocks. In the last recession, some famous ones collapsed!

3. Diversify. Although stocks usually win the race in the long term, you and I live in the short term. That means we need buffers: investments that give our capital some protection in a year (or years) when the economy falls apart and stocks decline. You need different types of stock funds because the various sectors perform differently at different times. You need international stocks, as well as stocks based in the United States. And you need bonds, for income and stability. Sometimes, bonds do better than stocks for extended periods. A historic bull market in bonds began around 1980 and continued through two huge stock market crashes, in 2000 and 2008. Super-safe Treasury bonds outperformed stocks over that entire 30-year period. Talk about a surprise! Just when investors settled into “stocks for the long run,” bonds turned out to have been the better choice. It seems unlikely that bonds will repeat that trick. At this point, I’d bet on stocks. But that’s why you diversify—because you never know.

4. Control your risk. This means thinking, in advance, of the consequences of being wrong. A good example would be borrowing all your home equity on the assumption that home prices would keep going up. You weren’t prepared, financially, when prices dropped. Good risk managers limit the size of their bets—whether on homes, stocks, or any other investment—so they won’t be wiped out if the bet turns out badly.

5. Keep it simple. Plain-vanilla stock and bond funds will do the job. All the other stuff—options, hedge funds, cash-plus funds, whatever—usually leave you wiser but poorer.

6. Reinvest your dividends. If I do no more than make you appreciate dividends, this chapter will have done its job. An investor who put $100 into the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock average on the last day of 1925, held until January 1, 2009—and spent all the dividends—would have earned $7,079. If that investor had reinvested all dividends, he or she would have had $204,526! That comparison is my all-time favorite financial fact.* Compounding interest and dividends is the investment world’s strongest, surest force.

7. Rebalance. Once you set your investment policy—say, 60 percent stocks, 40 percent bonds—you should maintain that allocation. If your stock funds go up in value, sell some to get back to the 60 percent of your portfolio they should represent. If your funds go down, buy some to bring your stock allocation back up to 60 percent. That’s called rebalancing. You’ll read more about it on page 710. For now, it’s enough to say that rebalancing can improve returns and minimize risk. It’s one of the secrets of investment success.

8. Invest regularly. Use a portion of every paycheck to invest in your mutual funds. Don’t worry about “bad” markets. Bad markets are good buys for long-term investors because stock prices are so low.

9. Forget market timing. Market timers try to sell when the stock market nears its peak and buy again when stocks bottom out. As if they knew. This game isn’t worth the candle because you are so often wrong. On a percentage basis, stocks rise more often and much farther than they fall. So the odds are on the side of the people who stay invested all the time, rebalancing as they go.

A study done by the University of Michigan for Towneley Capital Management in New York makes this point perfectly. The researchers looked at the 42 years from 1963 through 2004. They found that if you were out of the stock market during the 90 best days—just 90 days out of 42 years—you’d have missed an amazing 96 percent of all the market’s gains. Those magic days were scattered randomly over the entire period. One dollar invested in 1963 and not touched would have grown to $73.99. But if you had missed those 90 days, your dollar would have grown to only $2.70—less than you’d have earned from Treasury bills.

If you’d been on the sidelines during the market’s worst 90 days, your dollar would have multiplied to a breathtaking $1,693.68. But if you think you can pluck those few days out of a 42-year period, I’d say you’d been spending too much time in the hot sun.

There’s a name for timing gurus who claim to have consistently picked the market’s peaks and troughs: they’re called liars.

What’s your best protection against market drops? Steady investing, reinvesting dividends, diversification, and rebalancing. It’s important to buy when prices are low as well as when they’re high.

10. Stick to your investment policy. One year you’ll make money. One year you’ll lose money. But time is on your side. Don’t let impulse investing or sudden market changes shake you out of your long-term plan. Change your plan only if your personal circumstances change.

11. Have patience, patience, patience, patience. The urge for quick returns hurls you into lunatic investments—the financial equivalent of lottery tickets, with just about the same odds. Fear scares you away, even from sensible choices. A successful investor hitches a ride on the global economy’s long-term growth.

Having made such a strong pitch for buying stocks, I can hear the echoes coming back—“Yeah, but what about the bubble that burst in January 2000? What about

a market that made no net gain between 2000 and 2006?” What about the crash of 2008, which took the market back to price levels not seen since 1997?

Well, what about it? Those drops are temporary. No one knows what stocks will do tomorrow, but the evidence is clear as to how they’ll probably perform over 15 years. You will almost certainly make money. In the 15-year period ending in April 2009—covering the market collapse of 2008 and the copycat collapse of early 2009—long-term investors still reaped 6.5 percent a year with dividends reinvested.

Furthermore, you protect yourself against a decline in a single market, like the S&P 500, by owning other markets too. Take the period January 1, 2000, though the end of December 2007. The S&P went nowhere—up a mere 1.66 percent a year. During that period, international stocks, as measured by the MSCI EAFE index of stocks in developed countries (Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Japan) rose by 5.54 percent. You’d have improved your performance by owning both. They all dropped in the 2008 bust, but some recovered faster than others.

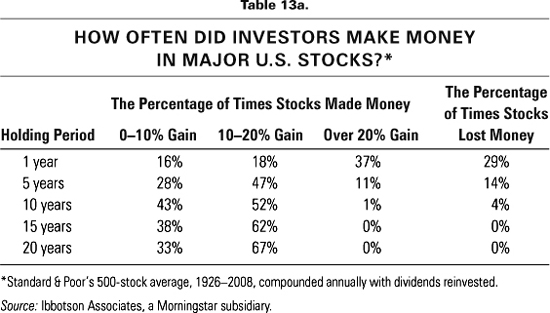

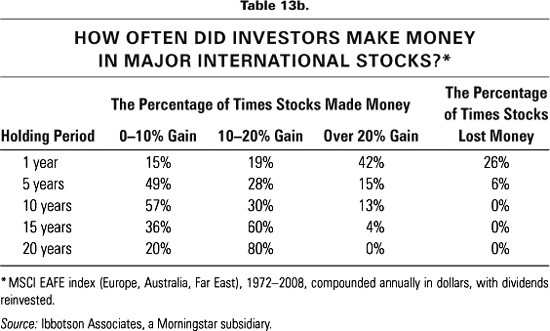

The tables on page 697 show the percentage of times that investors made money in U.S. and international stocks over various holding periods: 1 year, 5 years, 10 years, 15 years, and 20 years. The U.S. data start in 1926; the international data start in 1972. Here’s what you learn:

1. In any 1-year period, stocks are dicey. You get the biggest gains if you hit them right. But you also risk the biggest losses.

2. Over 5-year holding periods, your chance of loss is small. Over 10-year periods, it is negligible. The most recent 10-year period was one of the few losers for U.S. stocks but not for international stocks—one of the many reasons to diversify.

3. Over 15- and 20-year periods, your chance of loss is zero, provided that you reinvest your dividends. (You may lose money, however, if you don’t reinvest your dividends, a matter important to retirees who are living on dividends.)

4. The longer you hold stocks, the greater your chance of making money and the smaller your chance of losing it. During long holding periods, however, you’ll suffer through several stock market drops. If you panic and sell, you won’t get the superior returns that stocks can deliver. Best antidote: own a sizable cushion of high-quality bonds. They support your portfolio during bad markets, which can save you from your impulse to run. A written investment policy can help you too (page 694).

5. The longer you hold stocks, the greater your chance of earning an average return rather than a spectacular one. U.S. and international stocks turn out about the same. But they rise and fall at different rates and often at different times, so owning both will smooth your returns.

What about Murphy’s Law, which says that if anything can go wrong it will? Or Quinn’s Law, which says that Murphy was an optimist? In living memory, stocks have had three especially bad patches so far.

First, they were trounced by bonds during the early, and deflationary, 1930s. (The reincarnated among us will remember that bonds also rolled over stocks during the deeply deflationary 1870s.)

Second, in the inflationary 1970s, stocks (with dividends reinvested) finished modestly behind both corporate bonds and Treasury bills. Stocks hate superhigh inflation just as they hate severe deflation.

Third, in the postbubble 2000s, big-company U.S. and international stocks lagged behind bonds from January 2000 through mid-2009 (and maybe more; mid-2009 is when this book went to press).*

In most decades, however, stocks finished first, usually by a mile. They can do fine during modest inflation as long as prices aren’t accelerating by more than 4 percent. And they’re just as happy during modest deflations (although you have to go back to the nineteenth century for proof). That’s why smart investors emphasize stocks, with a prudent, age-appropriate diversification into bonds just in case.

Even during a bad patch, stocks can be rescued by the dividends they pay. Take the period from February 1966 to January 1983—17 long years. Stocks rose and fell and rose and fell but never advanced much higher than 1,000, as measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Investors earned zero in price alone. If they reinvested their dividends, however, they earned 7 percent a year. During that same period, long-term bond investors earned 4.3 percent.

Limiting losses is more important than many people realize.

When you ride stocks all the way to the bottom of a bear market, you wind up with fewer assets invested. That makes it harder for you to make up the money you lost. For example, say that you have $100,000 in stocks and the market drops 10 percent, leaving you with $90,000. To get even, you need an 11 percent gain. Now say that the market drops 25 percent, leaving you with $75,000. At that point, you need a 33 percent gain to return to $100,000 again. Recovering money lost isn’t as cut and dried as some investors think.

You may also imagine that fast-rising “growth” stocks do better over time than boring stocks (“value stocks”) that don’t rise as fast. But growth stocks also fall farther when the market drops. When prices start up again, the boring-stock holder has more money invested to catch the rise. At the end of a couple of up-and-down cycles, boring stocks usually win.

How do you beat this unhappy arithmetic? Don’t buy and hold. Buy and rebalance as the market falls (page 710).

When you open a brokerage account, you’re often asked to fill in a questionnaire. It’s supposed to tell the broker your tolerance for risk. Are you okay with aggressive investments that will plunge when the market falls? Or would you prefer something grayer and less exciting? Depending on your answers, a computer spits out an asset allocation that supposedly will suit your temperament to a T.

These questionnaires are bunk. You never know what your risk tolerance is going to be. When the market is rising, you’ve just had a promotion at work, or the sun is shining in a particularly lovely way, you may be inclined to bet the house. When the market falls, you’ve had a quarrel with your boss, or your kid got his third speeding ticket and your insurance premiums are about to jump, you may not feel like taking any risks at all.

So ignore whatever feelings are dominant today. Match your investments to your age (page 722) and to an assessment of what you’ll need the money for (page 706).

Some investors stay out of stocks in order to keep their money “safe.” But what does “safety” really mean? Bonds and bank accounts carry hazards that you haven’t thought about. A fixed-income investment can eat up your future just as surely as if you had fed it to sharks. You have to understand your whole range of risks in order to make good investment decisions.

Of all risks, the most familiar is market risk—the risk of losing money in a bad investment.

Adjust for this by (1) diversifying your investments so that a single loss (even though temporary) doesn’t leave a hole in your wealth, (2) buying only the boring old standbys such as diversified mutual funds, and (3) skipping the dizzy investment ideas that only a novice or maniac could love. If you’re dizzy at heart, give yourself a small mad-money fund to play with. I’ll wager that your boring investments come out ahead.

Everyone endures economic risk—the hit you take when the economy turns down. Adjust for this risk by minimizing investments that get bashed in recessions such as junk bonds and aggressive growth mutual funds. Those investments

soar in good times and may give you better long-term returns. But you have to be willing to suffer larger-than-usual losses when business sags. Hold a percentage of your money in high-quality bonds, which usually do well when the economy flags.

Less well understood is inflation risk—the risk of losing the purchasing power of your capital. This is the monster that eats fixed-income investors for lunch. After inflation, a certificate of deposit, zero-coupon bond, or traditional Treasury security yields little or nothing. An inflation-adjusted Treasury may preserve your purchasing power before tax but not after tax. After years and years of saving, you come out with a pittance in real terms. Inflation can devour stock investors too, on the rare occasion that the stock market goes nowhere for many years.

Adjust for inflation risk by (1) not keeping large, permanent sums of cash in money market mutual funds and similar short-term investments; (2) avoiding an all-bond portfolio, even in retirement; (3) buying some Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (page 407), which can at least preserve your capital pretax; and (4) putting at least some of your money into diversified stocks for growth. The table above shows how well (or how poorly) all the common investments survive inflation.

The consistency of long-term common-stock yields over inflation is nothing short of astonishing. The Ibbotson table above shows virtually the same returns over two different periods. Here’s another calculation, from Jack W. Wilson and Charles P. Jones of North Carolina State University, using a methodology that covers more stocks: From 1926 through 2008, holders of large U.S. stocks earned 6.11 percent annually after inflation, with dividends reinvested (6.79 percent before the 2008 market collapse). From 1871 through 1925, stocks earned 6.62 percent—again, very similar. Based on this record, it’s reasonable to expect that, 20 or 30 years from now, you’ll show close to a 6.5 percent return over inflation, whatever that may be. Charles Jones gives one warning: in the past, dividends averaged 4 percent, which accounts for more than half of the historical return. In recent years, they’ve averaged around 2 percent, which could reduce your future gains.

There’s deflation risk—not seen in the U.S. since the 1930s. The odds run against deflation, but if it occurred, cash and fixed-rate Treasuries would be a fine defense.

In our global economy, there’s dollar risk. This affects investors who hold international mutual funds. The value of your fund can rise for one of two reasons: (1) Foreign stock markets do well because those economies are growing. Or (2) the dollar falls against foreign currencies. When the dollar falls, holdings of international funds are worth more, in dollar terms. Similarly, the value of international funds can fall for one of two reasons: (1) Foreign economies are doing poorly, so their securities are worth less. Or (2) the dollar rises against international currencies, meaning that your funds are worth less in dollar terms. The performance of your stock fund will always be a combination of these two elements—economic results and currency changes. Bond fund performance depends almost entirely on currency changes.

Some international mutual funds try to hedge their dollar risk so their funds will do well even if the greenback’s value rises. But professional managers are no better than you and I at predicting currency changes, and hedging raises the costs investors have to pay. So don’t bother looking for funds that hedge. Just diversify internationally and let the dollar chips fall where they may.

For market timers, there’s error risk. Timers try to sell at market tops and buy when stocks are low. Often they get it wrong, losing money on both ends of the cycle. Their biggest risk is selling when stocks are partway down and waiting and waiting before they have the nerve to jump back in. By the time they decide to buy again, the market has typically turned around and moved up strongly. Historically, you lose more money by missing the upside than staying too long and enduring declines. Defend against error risk by not trying to time the market. Rebalance instead (page 710).

Bond investors face interest rate risk—the risk that interest rates will rise. When that happens, the value of your bonds or bond mutual funds falls and you lose money (or make less money than you expected). Furthermore, the income you’re earning may no longer beat inflation and taxes. Adjust for interest rate risk by owning short- to medium-term bonds (maturing in maybe 2 to 10 years). When rates rise, these bonds don’t fall as much in price as 20- or 30-year bonds.

Fixed-income investors also face reinvestment risk. Say that interest rates are rising and you have to choose between a one-year CD at 4 percent and a five-year CD at 3.5 percent. You decide on the higher rate. But when that CD matures, one-year rates may be down to 3 percent. That 3.5 percent you spurned last year is no longer available. You’d have made more money by going for the five-year CD originally.

Adjust for reinvestment risk in one of two ways: (1) Ladder your fixed-income investments. For example, you might own CDs or Treasury bonds maturing in one year, two years, three years, four years, and five years. Every year, when a CD or bond matures, reinvest it in a new five-year instrument. If interest rates have risen, you’ll get a higher rate. If they’ve fallen, you’ll still be getting high interest income from your existing investments, and you’ll have another shot at higher rates the following year. (For more on laddering, see page 67.) Some investors ladder up to 10 years. (2) Buy a bond mutual fund. There is always new money coming into funds. When interest rates rise, the fund manager will be buying those higher-yielding bonds, whose high rates will help offset any decline in market value. What’s more, you’ll be buying higher-rate bonds yourself through your reinvested dividends.

You also face reinvestment risk if you hold a callable bond (a bond is callable if the issuer can call it in before maturity). Take a 30-year tax-free municipal bond that’s supposed to pay 3.5 percent interest for another 20 years. If interest rates fall, the municipality will call in the bond after 5 or 10 years, and you can kiss that income good-bye. Adjust for this risk by buying munis with faraway call dates. For a tax-deferred account, such as an IRA, buy noncallable Treasury bonds.

Then there’s liquidity risk. A liquid investment can be sold immediately, at market price, if you suddenly find that you need some money. An illiquid investment can’t be sold fast except at a discount. Not all of your investments have to be liquid, but enough of them should be, to ensure you quick cash if you ever need it without having to take a loss. So what’s liquid?

A money market deposit account at a bank. You can get your cash at any time. Money market mutual funds are almost always liquid (although a large one failed in 2008 and froze its customers’ funds).

A money market deposit account at a bank. You can get your cash at any time. Money market mutual funds are almost always liquid (although a large one failed in 2008 and froze its customers’ funds).

A certificate of deposit is relatively liquid but not perfectly so. You can always get the money, but it may cost you an early-withdrawal penalty.

A certificate of deposit is relatively liquid but not perfectly so. You can always get the money, but it may cost you an early-withdrawal penalty.

Mutual fund shares are liquid. You can sell at any time, at current market value. If there’s an investing scare, the fund’s price may be down, but you can still get your money out. In a true panic, your fund has the right to suspend redemptions or delay mailing your check for up to seven days, but I can’t recall that ever happening in any mainstream fund.

Mutual fund shares are liquid. You can sell at any time, at current market value. If there’s an investing scare, the fund’s price may be down, but you can still get your money out. In a true panic, your fund has the right to suspend redemptions or delay mailing your check for up to seven days, but I can’t recall that ever happening in any mainstream fund.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are liquid. They’re mutual funds that are traded on the major stock exchanges (page 785).

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are liquid. They’re mutual funds that are traded on the major stock exchanges (page 785).

Individual stocks are liquid as long as they trade on the major stock exchanges.

Individual stocks are liquid as long as they trade on the major stock exchanges.

Gold bullion coins can be sold anywhere in the world but at a stiff discount from market price. Gold ETFs, by contrast, can be sold right away at market price.

Gold bullion coins can be sold anywhere in the world but at a stiff discount from market price. Gold ETFs, by contrast, can be sold right away at market price.

Retirement accounts are liquid in that you can usually cash them in. But I count them as illiquid because of the tax cost and penalty of breaking into them too soon.

Retirement accounts are liquid in that you can usually cash them in. But I count them as illiquid because of the tax cost and penalty of breaking into them too soon.

Small amounts of tax-exempt bonds are often illiquid. No one wants to buy them except at a steep discount.

Small amounts of tax-exempt bonds are often illiquid. No one wants to buy them except at a steep discount.

Real estate is generally illiquid. It can take months to sell, and even then you might have to mark down the property’s price.

Real estate is generally illiquid. It can take months to sell, and even then you might have to mark down the property’s price.

Precious gems are hugely illiquid. They’re salable, but the dealer may not offer you anything close to what you paid or what you think they’re worth.

Precious gems are hugely illiquid. They’re salable, but the dealer may not offer you anything close to what you paid or what you think they’re worth.

Your own business is illiquid.

Your own business is illiquid.

Shares of the exotic new financial instruments that Wall Street invented in the 2000s may become so illiquid in a market panic that they’re completely unsalable. Moral: buy the simple stuff, not the fancy stuff.

Shares of the exotic new financial instruments that Wall Street invented in the 2000s may become so illiquid in a market panic that they’re completely unsalable. Moral: buy the simple stuff, not the fancy stuff.

Adjust for liquidity risk by balancing illiquid assets with liquid ones. Anytime you buy something, ask: What happens if I want to sell? Can I get my money fast? Can I sell at market price without taking a discount or paying a penalty? If not, how long might I have to wait for my money? You should have enough liquid assets to carry you for a year even if no other money is coming in.

A risk almost no one thinks of is holding-period risk—the chance that you’ll have to sell an investment at a time when it’s worth less than you paid.

Say, for example, that you’ve been saving for a down payment on a house and are keeping the money in a stock-owning mutual fund. Three weeks before you’ll close on the house, the stock market drops. You lose 20 percent of your down payment, can’t buy the house, and your marriage breaks up. That’s holding-period risk.

Or say that you bought a 30-year zero-coupon bond (page 945) for your child’s college education. When college begins, the bond still has 15 years to run. You have to sell it to pay the tuition, but the market is down, no one wants a single bond unless you’ll chop the price, and you’re stuck. That too is holding-period risk.

I like stocks if the holding period will last for more than 5 years and you can tap other funds in case stocks happen to be down when the need for cash arrives. I love stocks for holding periods of 10 years or more. But I hate and fear stocks for periods shorter than 5 years because you cannot count on getting your capital out.

I fear 30-year bonds for any purpose but speculation on falling interest rates (page 924). I hate any bonds that will mature well past the date when I know that I’m going to need the money.

To adjust for holding-period risk, match your investments to how soon you’re going to want the funds.

Cash you’ll need within 1 to 2 years belongs in a supersafe place. Four possibilities: money market mutual funds, bank money market deposit accounts, short-term CDs, and short-term Treasury bills (page 225). They’ll preserve your capital while offering some inflation protection. (On money funds, your inflation protection is the fact that interest rates can rise. On CDs and three- or six-month Treasuries, you can roll over your investments at a higher rate.)

Cash you’ll need within 1 to 2 years belongs in a supersafe place. Four possibilities: money market mutual funds, bank money market deposit accounts, short-term CDs, and short-term Treasury bills (page 225). They’ll preserve your capital while offering some inflation protection. (On money funds, your inflation protection is the fact that interest rates can rise. On CDs and three- or six-month Treasuries, you can roll over your investments at a higher rate.)

Cash you’ll need in 3 to five 5 years could go into a CD. It might be okay in an ultra-short-term bond fund too, but for true security—with liquidity—I’d keep 3- to 5-year money in money markets too. When the credit bubble burst in 2008, one popular ultrashort fund dropped more than 15 percent in value. Not good for people who needed to get their money out.

Cash you’ll need in 3 to five 5 years could go into a CD. It might be okay in an ultra-short-term bond fund too, but for true security—with liquidity—I’d keep 3- to 5-year money in money markets too. When the credit bubble burst in 2008, one popular ultrashort fund dropped more than 15 percent in value. Not good for people who needed to get their money out.

Cash you won’t need for 5 to 10 years should be invested for income with a modest tilt toward growth. This is the window for bonds and mixed stock-and-bond funds (called equity income funds).

Cash you won’t need for 5 to 10 years should be invested for income with a modest tilt toward growth. This is the window for bonds and mixed stock-and-bond funds (called equity income funds).

Cash you won’t need for more than 10 years should be invested for income and growth. It’s always possible that the stock market won’t rise over that period of time. For example, large U.S. stocks went nowhere from 1998 to 2008. But for well-diversified investors, the odds of success are high.

Cash you won’t need for more than 10 years should be invested for income and growth. It’s always possible that the stock market won’t rise over that period of time. For example, large U.S. stocks went nowhere from 1998 to 2008. But for well-diversified investors, the odds of success are high.

Don’t forget expense risk. It’s hard to make money if you’re taking a chunk out of your assets to pay high expenses each year. The best predictor of mutual fund performance is cost—on average, the less you pay, the higher your net gain. Paying less than 1 percent is fine. Paying 3 or 4 percent, as you might for a variable annuity, is cutting yourself off at the knees.

I’d be neglectful if I didn’t mention idiot risk. That’s the risk that you will take an idiot’s advice about money (including that of all too many Wall Street professionals) or get swept up in a fad and act like an idiot yourself. Don’t kick yourself. We’ve all been there at one time or another. The trick is never to put a lot of money into anything you suddenly get excited about. No single investment should be large enough to endanger your standard of living if it goes wrong.

Finally, there’s investment book risk. Many of the investment returns you see here are averaged over calendar years. The same is true for most articles in personal finance magazines. But there are zillions of possible holding periods, which may produce higher or lower returns. Sophisticated financial planners use something called a Monte Carlo simulation. It looks at thousands of random possibilities to help you assess the chance of achieving average, above-average, or below-average results. If you work with a financial planner (chapter 32), he or she should have this capability.

You cannot escape taking some kind of risk, so the next thing to ask is whether your current range of risks supports or undermines your purpose. Here’s a general guide.

1. Use safe savings, with no market risk, for:

2. Use stocks for:

(continued on page 708)

4. Use long-term bonds for:

5. Use investment real estate for:

To find out if you’re carrying the right investments to support your personal goals, fill in the table on page 707.

First, list all your savings and investments, both inside and outside your retirement plan. Divide them into short term and long term. Then list your short- and long-term goals. Note that growth isn’t a goal, it’s a strategy. Early retirement and college tuition are goals.

When you’re finished, the table may show a mishmash of investments acquired without thinking what goals they should serve. The money you’re saving for a down payment might be in a bond fund instead of cash; your retirement savings may be in certificates of deposit. Later chapters will help you straighten all this out.

“But where’s the fun?” you ask. “Where are the kicks, the highs, the joys of the chase? I want to have some sport with my money!”

And why not? So do I. Over the years, I have fallen in love with one oil well (dry), one new venture (bankrupt), one glamour stock (down 80 percent, which is when I learned about stop-loss orders), and one of the worst mutual funds in history. I did make some money on some of my fliers (including that mutual fund, which I dumped before it went too far down). But that’s not the point. What matters is that I was gambling with play money, not with the bulk of my assets. My basic holdings were, and are, in a suitable range of sober investments for my old age.

I want you to get all the pleasure you can from the money you’ve earned. If that means rolling dice in a Wall Street crap game, so be it. Just don’t throw around your kid’s college tuition account or the life insurance proceeds meant to see you through widowhood. Fund your serious needs seriously. If there’s anything left over, do whatever you want with it.

A bull market goes up. A bear market goes down. A bear market rally, when stocks rise only to fall again, is a dead-cat bounce. A crummy stock is a dog. If you waste your brains throwing money at the hottest stocks, you’re a pig. No one who reads this book is a pig!

So far we’ve been matching appropriate investments and levels of risk with a whole range of personal objectives, short term and long. Now it’s time to consider pure long-term investing, such as parlaying your savings into enough to live on when you retire. Here other kinds of matching schemes come into play. You are asking the question: What return do I need from my long-term investments? How much risk am I willing to swallow to try to get it? Do I even know how much risk I’m willing to take? (When stocks plunge, minds change!)

Enter the concept of asset allocation. To explain it, let me start with a tale of two investors, as told by Marshall Blume, professor of finance at the Wharton School in Philadelphia.

Fighter Jock puts $100 into stocks in August 1929, just before the Great Crash. Measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average, with dividends reinvested, it takes him almost 16 years to get his money back.

Savvy Sal also has $100, but she puts $50 into stocks and $50 into bonds and maintains that 50–50 split. When her bonds are worth more than 50 percent of her capital, she sells some and buys stocks. When her stocks are worth more, she sells some and buys bonds. That’s called rebalancing. She rebalances every month (Blume is measuring by the market averages here), always seeking to keep half of her money in each investment. In just six years, she recovers her original stake.

Notice what Sal did not do:

She did not sell all her stocks at the bottom and give up the market for ever and ever.

She did not sell all her stocks at the bottom and give up the market for ever and ever.

She did not try to guess when the market would rise or fall again. She just followed her investment formula.

She did not try to guess when the market would rise or fall again. She just followed her investment formula.

She did not let herself be swayed by the news of the day. Instead she invested for the long term.

She did not let herself be swayed by the news of the day. Instead she invested for the long term.

She did not fail. She beat Fighter Jock, who bought stocks and held them. And she beat the investors who fled the market and put their money in the bank.

She did not fail. She beat Fighter Jock, who bought stocks and held them. And she beat the investors who fled the market and put their money in the bank.

Sal practiced asset allocation, which, simply put, means dividing your money among stocks, bonds, cash, and other kinds of investments. She also practiced rebalancing, which means keeping each type of investment at the same percentage you started with, even when the market changes. People don’t pay a lot of attention to asset allocation and rebalancing. Yet they’re the two key decisions that determine your investment success, not how smart (or dumb) you are at picking stocks or mutual funds.

“But wait,” you say, “Sal was just lucky. What would have happened had stocks bounced right back after 1929?”

In that case, Fighter Jock would have done somewhat better. But from time to time, he’d have taken a big loss.

Sal would have taken occasional losses on her stocks as well as her bonds. But because she owned both, her total portfolio of investments would never have dropped as far as Jock’s. Her long-term results would still have been fine, without as much fear along the way.

But the fact remains that stocks didn’t bounce back after 1929. And Sal was positioned to handle that risk. Balanced portfolios did better after the 2000 bubble too.

To rebalance means to keep your investment portfolio on an even keel. You want to hold roughly the same percentage of your money in stocks no matter what the market does. That keeps your account from getting either too risky or too conservative, too exposed to stock market declines or too conservative to grow. You’re aiming for a steady course.

To start the process, you have to decide what your balance should be—how much in stocks and how much in bonds. As an example, I’ll assume that you’re putting 60 percent of your investment money into a stock mutual fund that copies the behavior of the market and 40 percent into a bond mutual fund that does the same. That’s your home base. (Funds that copy the market are called index funds—see page 745.)

As market prices change, however, the ratio of stocks to bonds will change as well. If stocks zoom up, they might soon account for 70 percent of the value of your investment portfolio. You’ll feel rich, but you’ll also be in a riskier position. If the rally fails, you’ll have more to lose. So you rebalance. You sell some of your stock fund (at a profit) and put the proceeds into your bond fund. That returns you to your original 60–40 split between stocks and bonds.

The next year, stocks might do poorly—dropping in value to only 50 percent of your portfolio. Your investments have now become too conservative, with too little money invested for growth. This time, you’d sell bonds and reinvest the proceeds in stocks to raise your stock allocation back to 60 percent.

You handle all the investments you own in the same way. If you start with 20 percent in an international fund and price changes raise its value to 25 percent of your money, you’d sell some of the shares to bring it back down to 20 percent and reinvest the proceeds in your U.S. stocks or bonds.

Rebalancing makes you a smart investor—much smarter than people who keep on chasing hot mutual funds. The chasers buy at high prices, then get disappointed and sell when prices drop, locking in a loss. Rebalancers do the opposite. You are selling at high prices (taking profits) and reinvesting in lower-priced assets that haven’t done as well. Those slower performers will eventually go up, and you’ll make money because you bought them cheap. Remember, the types of assets that were yesterday’s losers will be tomorrow’s winners. A faithful rebalancer buys tomorrow’s winners automatically.

Rebalancing is also a smarter strategy than buy and hold. If you always stand pat in a falling market, you give away the profits you made when stocks ran up. You also lose the chance to buy more stocks at the bottom when they’re cheap. Market timers try to guess at the magic moments to buy and sell—and over time, they’re going to lose. Rebalancers practice a discipline that reaps some of the advantages of successful market timing without getting you into trouble.

Sometimes rebalancers kick themselves. The market shoots up, you sell some of your stock position, and prices go higher yet. Then the market declines and you buy some stock, only to see prices drop even more. “Hey,” you say, “wasn’t I supposed to cut my losses and let my profits run?” Sure, except how are you supposed to know when the run is over and when to cut? Rebalancing works over time. When you practice it faithfully, you’ll look back and see that it steered you right.

How do you rebalance? That depends on where the money is:

1. In a tax-deferred retirement account such as a 401(k) or IRA, rebalancing is easy. You’d sell some of the shares you hold in the investment that went up and reinvest the proceeds in investments that lagged. You might be able to make the changes yourself online. Some plans can be rebalanced automatically. Or call the plan’s customer service center. No taxes or penalties are involved. The service rep might even help you make your rebalancing calculations.

2. If you’re investing outside a retirement fund, you should handle rebalancing in a different way. You don’t want to sell investments that rise in value, because you’ll owe taxes on the gain. So leave them alone and rebalance by adding extra money to asset that fell behind. As an example, say that you’ve been putting $200 a month into your investment account—$120 into a stock fund and $80 into a bond fund, for a 60–40 split between stocks and bonds. After a good year, your stocks are now worth 70 percent of your portfolio. To bring your investments back into balance, start adding the whole $200 a month to your bond fund until its value rises back to 40 percent of your total investment.

Rebalancing works best for mutual fund investors, who can easily sell shares in one fund and move to another. It works especially well for index fund investors (page 745), because your funds are clearly divided into different investment types. You know exactly which fund to buy and which one to sell when your portfolio falls out of balance. It doesn’t work well when you own a portfolio of individual stocks. Deciding which stocks to sell or how much of each position to sell gets too complicated. Moral: get smart, use mutual funds.

There’s no need to rebalance after every little wiggle in the stock market. Do it only if one investment misses its home-base target by more than 5 percent, up or down. Check your investments once a year to see if you should act. You can get help with these calculations if you keep track of your finances with the latest versions of Quicken Personal Finance and Microsoft Money. Both products offer rebalancing programs that will tell you instantly whether you ought to sell or buy and, if so, how much.

You’ll hear me say over and over again that smart investing is easy. You save money regularly, set yourself an investment policy using mutual funds, and rebalance. End of story. But I have to confess that rebalancing can be hard—not mechanically but psychologically. You’re selling stocks as their price goes up, when your every impulse is to hold or buy. If prices keep going up, you’ll kick yourself for selling “too soon.” The opposite happens on the downside. When stocks decline, you’re supposed to buy. If you get scared and sell instead, you won’t get the long-term advantage that this strategy brings.

Rebalancing takes discipline and courage. The only way to stand the strain is to hold a really deep belief that rebalancing works. To reinforce your belief, remember the stock market bubble. Wouldn’t it have been nice if you’d sold some stocks when prices went sky-high? Wouldn’t it have been nice to reinvest in bonds, which rose in value during the years that stocks collapsed? Rebalancing could have done that for you. It works over every stock market cycle, all the time.

The best idea: let someone else rebalance for you. Many 401(k) plans now have a rebalancing feature. You might be able to: (1) press a “rebalance” button online, to have your investments adjusted; (2) call the plan’s manager and ask how to rebalance; (3) invest in your plan’s target-date retirement fund, which rebalances your investments for you automatically; (4) choose a 401(k) managed account. The manager picks funds and rebalances for you.

You can also invest in target-date funds outside a 401(k)—in your taxable account or individual retirement account. For more on target-date funds, see page 846. To me, they’re best buys. Anything that helps you rebalance will improve your returns over time.

A mutual fund is a big pool of money, contributed by thousands of people just like you. The manager of that money invests it in stocks, bonds, or both. Your share in the fund gives you a tiny ownership interest in all the fund’s investments. You’re spreading your money around, which is the right thing to do. There are many different types of funds. I’ll explain them and how to use them in chapter 22. Here I want to show you why they work so much better than buying individual stocks.

Mutual funds have three big virtues:

1. They make it easy to construct an investment policy. You can match the types of funds with the types of investments you want to hold. An easy call would be international stocks. Instead of hunting for specific foreign companies, you’d buy an international mutual fund. Or say you wanted to bet 10 percent of your money on U.S. stocks that are probably underpriced. Do you know which stocks those are? I don’t. But you can buy a “value” fund that specializes in those kinds of companies. Successful investors start with an investment policy (page 694), and mutual funds make it easy to carry that policy out.

2. They make it easy to rebalance. If the U.S. stock market goes way up, you’ll want to sell some of your position and invest the proceeds in an asset that has not performed as well—for example, bonds. If you own individual stocks, however, which ones would you sell? The ones that performed the best? A portion of all the companies you own? Who knows? If you own mutual funds, it’s simple—just sell a percentage of your fund shares.

3. They save you from making huge mistakes. If you own a substantial amount of a stock that goes bad, it wrecks your performance. The right mutual funds (see chapter 22) keep you so well diversified that one bad company won’t get you into trouble.

For some people, buying mutual funds goes against the grain. You think that your job is to find “great companies” and hold their stocks forever. But “great companies” don’t necessarily last. The superstars of 1990 were has-beens by 2000. The leaders in 2000 soon saw their stocks collapse. In hindsight, you can always find stocks with wonderful long-term records. Going forward, however, you can’t know which stocks will be the big winners (or losers) in the decade ahead.

Even if you know that you’re supposed to diversify your investments, maybe you don’t know why. A lot of study has established several things:

1. Different types of investments tend to move in different cycles. Some may go up, while others go down. Some go in the same direction, but not at the same time or at the same speed. Some move by larger percentages than others. Owning different types of investments protects you from big losses in your total portfolio and can improve your returns.

2. When you buy isn’t nearly as important as what types of assets you buy and how much you own of them. You can be all wrong on your market timing and still do well if you are properly diversified.

3. Market timing (which means buying before the market goes up and selling before the market goes down) is extraordinarily hard to do. The average investor won’t guess right often enough to beat the investor who buys and holds. Most professional investors don’t do much better. You definitely won’t beat the rebalancer. The Forecaster’s Hall of Fame is an empty room.

4. Almost no one, including investment professionals, “beat the market” over the long term. It’s a waste of time to set that kind of standard for yourself or to invest with that phony goal in mind. It will lead you wrong.

5. You cannot predict which types of investments—known as asset classes—will do better over the next five-year period. U.S. stocks? European stocks? Emerging markets? Bonds? Treasury bills? Who knows?

These findings lead to the conclusion that you shouldn’t break your head trying to predict what will happen to stocks, interest rates, or the economy. Don’t seek truth in the financial press. Don’t consult gurus. Don’t be stampeded into the market, or out of it.

Instead focus on what you’re investing for (page 707). Then split your money among the types of investments most likely to achieve that goal. And stick with them. Amen.

To minimize risk, you need a mix of investment types that rise and fall at different times or at different speeds. Each type is called an asset class. In the real world, no investments counter one another quite that neatly. Nor do they maintain their relationships consistently. In general, however, here’s how the various assets move in relation to one another:

In case of unanticipated inflation, you want Inflation-Adjusted Treasury Securities (TIPS), gold, or money market mutual funds. Real estate can work too, although very slowly over time. Commodities are wild cards. They often rise during inflationary times, but not always.

In case of unanticipated inflation, you want Inflation-Adjusted Treasury Securities (TIPS), gold, or money market mutual funds. Real estate can work too, although very slowly over time. Commodities are wild cards. They often rise during inflationary times, but not always.

For anticipated (but moderate) inflation and economic growth, you want U.S. and international stocks. You also want stocks during periods of mild disinflation, when consumer price increases are gradually going down. To diversify among U.S. stocks, you need mutual funds dedicated to small companies, large companies, value stocks (low priced and unloved), and growth stocks (earnings rising rapidly). For more on value versus growth, see page 874. To diversify among international stocks, you need funds in developed markets such as Europe and Japan and in emerging markets such as Brazil, India, and China.

For anticipated (but moderate) inflation and economic growth, you want U.S. and international stocks. You also want stocks during periods of mild disinflation, when consumer price increases are gradually going down. To diversify among U.S. stocks, you need mutual funds dedicated to small companies, large companies, value stocks (low priced and unloved), and growth stocks (earnings rising rapidly). For more on value versus growth, see page 874. To diversify among international stocks, you need funds in developed markets such as Europe and Japan and in emerging markets such as Brazil, India, and China.

In case of economic slowdowns, you want high-quality, noncallable long-term bonds—which means Treasuries.

In case of economic slowdowns, you want high-quality, noncallable long-term bonds—which means Treasuries.

If we ever see actual deflation, with price levels falling, you’d want Treasuries too. Stocks can do well during a moderate deflation, depending on what the economy does, but they get creamed during severe deflations.

If we ever see actual deflation, with price levels falling, you’d want Treasuries too. Stocks can do well during a moderate deflation, depending on what the economy does, but they get creamed during severe deflations.

To stabilize the value of a portfolio, you want cash equivalents (money market mutual funds, short-term Treasuries) and short- to medium-term bonds.

To stabilize the value of a portfolio, you want cash equivalents (money market mutual funds, short-term Treasuries) and short- to medium-term bonds.

To prevent weight gain, hair loss, acne, and wrinkles—and to confront an unknown future—you want a stake in all of these investments. The exact mix, however, has to be matched to your personal needs (page 707) and will change over time.

To prevent weight gain, hair loss, acne, and wrinkles—and to confront an unknown future—you want a stake in all of these investments. The exact mix, however, has to be matched to your personal needs (page 707) and will change over time.

To keep it simple, you want to own most of these investments through mutual funds.

To keep it simple, you want to own most of these investments through mutual funds.

You have not diversified if you own 15 stocks. It takes a minimum of 50, spread carefully over many different size companies and types of industries, to approach a proper U.S. mix.

You have not diversified if you own five growth mutual funds. Those managers all pick the same kinds of stocks and they’ll rise or fall in tandem.

You have not diversified if you own all stocks or all U.S. mutual funds, even if they’re different classes of stocks.

Nor have you diversified if you buy a bond fund, a Ginnie Mae fund, and some certificates of deposit. These too are much alike.

At minimum, you need a mix of U.S. stocks, international stocks, and high-quality medium-term bonds. An investor with more money will add emerging-market stocks and commodities. Real estate also belongs in the pot. Beyond your own house, consider real estate investment trusts.

When the markets collapsed in September and October 2008 and again in February 2009, there was nowhere to hide. All the risky assets fell together—every class of U.S. and international stock, real estate investment trusts, commodities, gold, high-yield bonds, and corporate and municipal bonds. The only bright spot was U.S. Treasury securities.

You might assume from that dismal record that broad diversification isn’t worth it because it doesn’t protect you when the market drops. That would be the wrong conclusion. You shouldn’t draw up a long-term investment strategy based on a once-in-a-lifetime (we hope!) global financial meltdown.

The right conclusion is that you should look at your investment portfolio in two ways: What helps you when stocks are moving up, and what protects you when stocks are moving down?

In rising markets, stock diversification pays. You should own large stocks, small stocks, U.S. stocks, international stocks, and emerging-market stocks. These various classes of investments rise at different times and at different rates of speed. If you invest in just one of them—say, U.S. stocks—you run the risk of choosing a market that doesn’t do as well as the other ones. To keep the wind in your sails, you want to own all types of stocks, across the board.

In falling markets, however, all these classes of stock will plunge at roughly the same time. Your equity diversification won’t help you at all. To limit your risk in down markets, you should own Treasury securities, cash, and very-high-quality corporate or municipal bonds.

It’s not possible to guess when those random bad markets will come along. For that reason, your long-term investment portfolio should contain both diversified stocks and a permanent allocation to diversified bonds, in an amount appropriate to your age (page 723). Just be sure to make them high-quality bonds. High-yield (low-quality) bonds tend to fall in price when the stock market does, so they don’t reduce your risk.

The second lesson is how to assess your exposure to risk. Typically, you measure risk by the length of your holding period—as I have on page 697. The longer you hold a portfolio of diversified stocks and reinvest the dividends, the less likely your chance of losing money over the entire term.

But it’s a mistake to focus only on your investment’s theoretical ending date—say, 15 or 20 years from now. That assumes you’ll be able to withstand the occasional market crash prior to that date, which may not be the case. On the way to its (presumed) positive, long-term result, your portfolio might suffer several declines of 20 percent or more.

The longer you hold your stocks, the more likely it is that such a collapse will occur. Looked at that way, your stock market investment grows riskier, not safer, with time. If you hold too much in stocks, one of those crashes might drive you out of the market entirely or force you to lower your stock allocation to protect the money that remains.

That’s another reason to leaven your stock portfolio with a hefty portion of bonds. During one of those temporary stock market drops, your bonds will keep enough of your money safe that you can afford to stay the course.

Selecting an appropriate level of risk means more than choosing among stocks and bonds. Within any class of investment, some types of securities carry more risk than others.

Say, for example, that you’re buying stocks to help fund a college education for your kids. A conservative investment would be a mutual fund that buys blue-chip, dividend-paying companies. An aggressive choice would be a fund that buys the stocks of small companies or companies in Southeast Asia.

If you want bonds, a conservative choice would be Treasuries, an aggressive choice would be junk bonds.

So you really have two decisions to make: (1) What mix of investments best suits your needs? (2) Within each investment class, how much risk do you want to take?

A Fixed Mix Versus a Flexible Mix. Within the Church of Asset Allocation, two theologies are at war. One says: fix your portfolio at whatever mix of assets is right for you and stay there until circumstances change (which is my view). The other says: keep changing the amount you hold of each type of asset, to focus on whichever market you think is the strongest.

With a fixed mix, you might own, say, 45 percent U.S. stocks, 25 percent international stocks, and 30 percent bonds. From time to time, you’d check your portfolio to see if it needs rebalancing. That means bringing everything back to the percentages that you started with. In general, you rebalance when your investment mix gets out of line by 5 percent.

With a flexible mix, you might decide that U.S. stocks will make up, say, 30 to 70 percent of your portfolio. When times look good, you’ll put in 70 percent; when you get worried, you’ll cut back to 30 percent.

In other words, you try to time the market, guessing when it will rise or fall. And not just one market but perhaps four or five of them, depending on how diverse your portfolio is. To me, this is a gambler’s game. It adds greatly to your chance of loss. I’m a fixed-mix type of dame.

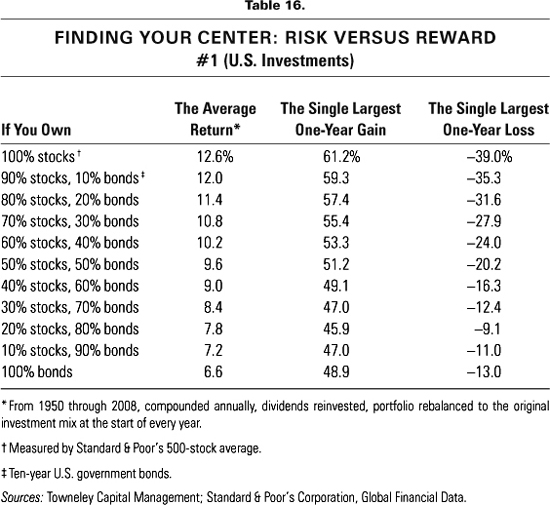

Tables 16 and 17 take some of the guesswork out of allocating assets among U.S. stocks, bonds, and cash. They help you decide how much risk you are willing to tolerate in order to earn a desirable return. The first table, covering stocks and medium-term Treasury bonds, was prepared by Towneley Capital Management, an investment advisory firm in New York City. The second table, for stocks, medium-term Treasuries, and cash, comes from the mutual fund company T. Rowe Price. Here’s how to use the data.*

Read down the columns headed “The Average Return.” They show the average long-term return you can expect if you hold the indicated mix of investments. When you see a return that looks good to you, read across to the “loss” column. There you’ll find the largest percentage loss that that particular mix of investments has ever had in a single year. In table 16, for example, the all-stock portfolio with a 12.6 percent return once lost as much as 39 percent. You recover those losses in later years but must be prepared to suffer through.

If the loss looks too scary, read on down the column until you find a one-year loss that seems tolerable. Then look back to the first column to see what mix of investments you’ve chosen and what your average return is likely to be. If that return looks too low, rethink the size of the one-year loss that you’re willing to risk (remembering that these losses are temporary).

That’s investing in a nutshell. You are looking for the highest possible return commensurate with the risk you’re willing to take.

The middle column, by the way, is strictly for fun. It shows the kind of luck you might have in a superior year, in both stocks and bonds. But it shouldn’t enter into your investment decision. Long-term investors won’t earn the single highest return; they will earn something closer to the average return.

These tables are pretax, so they’re for people who are investing their retirement accounts. Your returns will vary if you’re investing after tax.

For safety with minimal risk, don’t choose an all-bond portfolio. Always include some stocks. For proof, look at table 16 and compare the portfolio fully invested in Treasury bonds with the one that contains 70 percent bonds and 30 percent stocks. The mixed portfolio had a higher average return and a smaller maximum one-year loss. Then look at table 17. The all-bond portfolio gives you poorer returns—and with more risk—than a portfolio combining bonds and cash with a modest amount of stocks. Diversification wins again.

For maximum growth potential, choose all stocks—at least for that portion of your money available for long-term investment. Stocks show the highest risk of loss in a single year but the biggest average gain over time. You’ll want to take the risk, however, only when you’re young and have a lifetime of paychecks in front of you. As you grow older and your future earnings potential shrinks, you should gradually shift money into bonds. Bonds provide your portfolio with the security you’ll need as you reach midlife. (For more on bonds, see chapter 25.)

For growth with less risk, add bonds to the portfolio rather than cash. The risks are about the same, and bonds give you a slightly higher return. Cash belongs in regular, taxable accounts, for paying your future expenses.

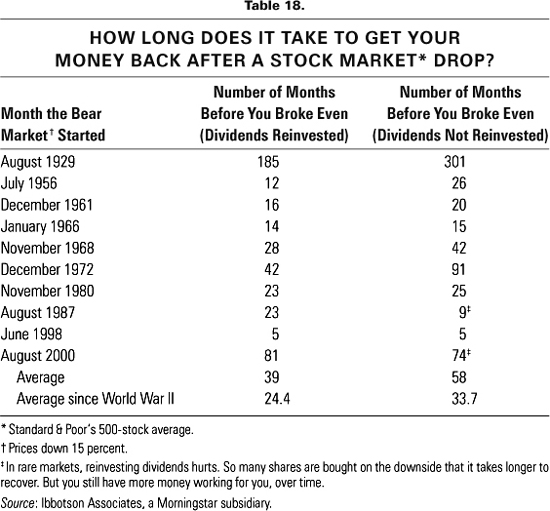

There’s one more thing that you might want to know about investment risk—namely, your break-even time. Say that you hold stocks at a bull market peak and then a bear market slide sets in. You didn’t rebalance (tut-tut), so you’re stuck with holding your securities until they recover. How long will it take before you get your money back? The following table gives you the answer for every 15 percent decline since 1929. One column assumes that you reinvest all your dividends; the other assumes that you cash the dividend checks and spend them.

Two points to note: (1) I draw my personal risk assessments from the period since World War II. After 2008, the 1930s started looking more relevant. Still, the financial structure was different then. (2) Reinvesting dividends gives you an enormous payback, especially after long bear markets. Each reinvested dividend gains value in the subsequent market rise. With this strategy it usually takes much less time to get your money back.

Take your age and subtract it from 110. The resulting number is the percentage of your assets that you should put into stock funds with the rest in bond funds. If you’re 30, put 80 percent into stocks. At 50, hold 60 percent in stocks. At 70, hold 40 percent in stocks. And so on.

This rule of thumb accounts for the fact that you need more asset growth when you’re young and more security as you age. It also gives you a money cushion when stocks decline. Even at younger ages, you might suddenly need some cash. Holding part of your investments in bond funds gives you something to sell if you urgently need money at a time when stocks are down. Bonds hold their value better than stocks, so you won’t be forced to sell investments at a loss. For help in using this rule of 110 to get you safely through retirement, see page 1141.

You need to take a total-portfolio approach. Put all your assets in a pot, then divide them into the types of investments that serve your personal time horizon and control your risk. You’ll find specifics on all these investments in later chapters. Here you’re constructing your battle plan.

What follows are examples, not gospel!! Every investor is a little bit different as to wealth, health, income, expectations, needs, and financial responsibilities. Every investment adviser will have different ideas about how portfolios should be constructed. Every time period is marked by different tax laws, interest rates, and market conditions—all of which influence portfolio choices. But the suggestions below are reasonable frameworks with which to start.

When tracking your progress, don’t look at just one of your investments. Your stocks might slide by, say, 10 percent, giving you a scare. But all types of investments rise and fall periodically. That’s why you diversify, so you’re not dependent on just one thing. If your stocks are down 10 percent but your bonds are up 3 percent and you have some cash, your total portfolio might be down by only 2 percent. That’s the measure to go by.

Here are some portfolio suggestions for people of various ages. For more on the types of mutual funds to buy, see chapter 22. For bonds, see chapter 25.

1. Cash reserve—in a bank or money market fund.

2. Retirement account—as heavily into stock funds as you can stand. Consider target retirement funds, stock-index funds, value funds, growth funds, internationals, and emerging markets.

1. Cash reserve—in a bank or money market fund.

2. Inflation hedge—a house and the stock funds in your college and retirement accounts. The value of your home should rise with the inflation rate once the bad 2006–2009 housing market rights itself.

3. College account—consider an age-based account in a tax-exempt 529 plan (page 664). When your child is young, the account is heavily into stocks. As he or she moves through the teenage years, it automatically switches toward bonds and cash. When tuition is due, you’ll have no-risk money on hand. Follow this same system if you’re handling your own investments, inside or outside a 529.

4. Retirement account—as heavily into stocks as you can stand. Consider target retirement funds, stock-index funds, value funds, growth funds, internationals, and emerging markets. For bonds, consider Treasuries, general bond funds and high-yield funds.

5. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

1. Cash reserve—in a bank or money market fund.

2. Inflation hedge—a house, maybe a vacation house, the stock funds in your college and retirement accounts, and some inflation-protected Treasury bonds. The value of your home should rise with the inflation rate once the bad 2006–2009 housing market rights itself.

3. College account—consider an age-based account in a tax-exempt 529 plan (page 667). When your child is young, the account is heavily into stocks. As he or she moves through the teenage years, it automatically switches toward bonds and cash. When tuition is due, you’ll have no-risk money on hand. Follow this same system if you’re handling your own investments, inside or outside a 529.

4. Retirement account—consider a long-term mix of medium risk rather than high risk. Maybe 65 percent stocks, 35 percent bonds (you can’t afford too much stock market risk in case there’s a problem with your health or job). For stocks, consider the usual suspects: target retirement funds, international funds, emerging markets, stock-index funds, and growth-and-income funds, but perhaps with more emphasis on the latter. For bonds, consider Treasuries, general bond funds, and high-yield funds. Outside a retirement account, use tax-deferred municipal bonds.

5. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

1. Cash reserve—a paid-up credit card. (All your cash is in the hands of the college bursar! Your only emergency money is your credit line.)

2. Inflation hedge—a house, maybe a vacation house, the stock funds in your retirement account, and some inflation-protected Treasury bonds. The value of your home should rise with the inflation rate once the bad 2006–2009 housing market rights itself.

3. College account—in savings bonds, Treasuries, short-term bonds, or bank CDs timed to mature when semesters begin. An age-based account in a 529 plan should do this for you automatically if it’s properly invested.

4. Retirement account—consider a long-term mix of medium risk (page 726) rather than high risk. For stocks, it’s international funds, emerging markets, stock-index, and growth-and-income, perhaps with more emphasis on the last. For bonds, consider Treasuries, general bond funds, and high-yield funds. Outside a retirement account, use tax-deferred municipal bonds.

5. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

1. Cash reserve—enough money in a bank or money market mutual fund to cover 24 months of current expenses not paid by your pension and other regular income. Enough in a money fund, CD, or short-term bond fund to cover 4 more years of current expenses. (For more on retirement investing, see chapter 30.)

2. Inflation hedge—a house, maybe a summer house, your common-stock funds, and some inflation protected Treasury bonds. The value of your home should rise with the inflation rate once the bad 2006–2009 housing market rights itself.

3. Retirement account—a long-term allocation of moderate risk; say, 45 to 55 percent stocks and the rest in bonds. Consider stock-index funds, growth-and-income funds, value funds, growth funds, and internationals. For bonds, buy Treasuries, intermediate- and short-term bond funds, high-yield funds, or individual bonds. Outside a retirement account, use tax-deferred municipal bonds.

4. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

1. Cash reserve—enough money in a bank or money market fund to cover 24 months of expenses not paid by your pension, Social Security, and other regular income. Enough in a money fund or short-term bond fund to cover 3 to 4 more years of current expenses. For more on retirement investing, see chapter 30.

2. Inflation hedge—a house, maybe a vacation house, stock funds, and inflation protected Treasuries. The value of your home should rise with the inflation rate once the bad 2006–2009 housing market rights itself.

3. Retirement account—a long-term allocation of moderate risk; maybe 30 to 35 percent stocks with the rest in bonds. Consider stock-index funds, growth-and-income funds, value funds, growth funds, and internationals. For bonds, buy Treasuries, intermediate- and short-term bond funds, high-yield funds, or individual bonds and ladder them (page 67). Outside a retirement account, use tax-deferred municipal bonds.

4. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

1. Cash reserve—enough money in a bank or money market fund to cover 1 to 5 years of expenses not paid by your regular retirement income. Also, a firm determination to spend your principal as well as your income, if that’s what it takes to live comfortably. To make your money last for life, see chapter 30.

2. Inflation hedge—a house, stock funds, and inflation-protected Treasuries. You’ve sold your vacation house and reinvested the proceeds for income and some growth. Why growth? Because you could easily live for another 30 years.

3. Retirement account—a stock/bond mix of medium risk, if you have enough pension and Social Security income to live on. Concentrate on stock funds that pay high dividends, such as equity-income funds. Buy intermediate- and short-term bond funds, or buy individual bonds or CDs and ladder them (page 67). Choose a low-risk portfolio, maybe only 20 percent stocks, if your current income is insufficient and you’re dipping into principal to pay the bills. You can’t afford the risk of losing money in a stock decline. For bonds, choose Treasuries, intermediate- and short-term bond funds, and laddered individual bonds. Outside a retirement account, choose tax-exempt municipals.

4. Deflation hedge—Treasury bonds with fixed interest rates.

What if all your retirement money is in company plans that don’t allow the investment choices suggested in the sample portfolios? Your plan should at least

have a stock fund and a fixed-income fund. Given these choices, younger people should put most of their money into stocks—especially an index fund or target retirement fund if you’re offered one. It doesn’t matter that you might leave the company in five years; you can roll that money into an Individual Retirement Account and keep it invested in stocks. In early middle age—say, age 45—you might want 65 percent of your money in stocks. At 60, your stock allocation might drop to 50 percent (see rule of 110, page 722). These are only examples, but they indicate a direction.

Don’t make the mistake of diversifying your retirement savings separately from your other savings. Conceptually, you possess a single sum of money, some of it in the retirement account, some of it not. Your diversification plan should be tailored to that sum of money as a whole. The investments outside your retirement plan can fill in the gaps that the plan doesn’t offer.

For example, your 401(k) plan might restrict your stock investments to U.S. mutual funds, so use your outside money to diversify into an international fund. Alternatively, allocate higher investment risks to your retirement plan (because you won’t touch that money for 20 years or more) and choose lower risks for the savings that you keep outside the plan (because that’s Junior’s college money, which you’ll need 5 years from now).

You get the idea: count all of your money when deciding whether you’re properly diversified. Married couples should consider both spouses’ portfolios as a unit. You might run your money separately, but you’re going to retire together, and your standard of living will depend on what’s in the common pot.

It’s no mystery.

Live on less than you earn.

Invest the surplus.

If that doesn’t work, inherit.

Don’t look to the stars, look to yourself, as the great playwright wrote. You read all this stuff about steady investing and nod your head. But in a bear market, you may forget your good intentions. Our attitudes and emotions tend to undermine the strategy we set. Mastering these emotions is just as important as mastering an investment discipline. Here are the most common mental errors:

1. Fear of loss. We’re more alarmed by a minor loss than we’re cheered by a major gain. To prevent these temporary losses, we panic and sell or invest more conservatively than we should. Antidote: become a rebalancer (page 710), to check your tendency to cut and run. To encourage growth investing, study the market’s past performance. See how little you get from conservative income investments after taxes and inflation.

2. Short-term focus. If the mutual fund in your 401(k) loses money over 6 or 12 months, you might sell it and shift to something “safer.” Conversely, you might leap into a fund that currently tops the performance list. Antidote: keep checking Morningstar (www.morningstar.com), the publisher of mutual-fund data, to see which funds are currently ahead. A fund that’s hot for six months often cools in the next six months and vice versa. Once you’ve chosen a fund for good reasons (chapter 22), stick with it for 3 or 4 years unless the fund’s management and objectives or your circumstances change.

3. Fear of making the wrong decision. With so many investments to choose from, some investors freeze. They leave their money in the bank or the fixed-income account in their retirement plan. They leave it in mutual funds that they know are unsuitable because they’re afraid to change. They might hand it over to someone to manage without knowing much about the person they’ve handed it to. Antidote: this book, of course! Keeping your money in its usual place is a decision too—and often the wrongest one of all.

4. Fear of regret, also known as hindsight bias. You’re afraid that you’ll hate yourself in the morning. You should have bought that East Asian fund that rose 25 percent instead of the balanced fund that did only 10 percent. You should have switched to a money fund this year because stocks went down. Self-recrimination produces one of two effects: you do nothing, so you won’t have to kick yourself around; or you desperately try to catch up by jumping into that East Asian fund (too late). Antidote: proper asset allocation and rebalancing. Simple and steady gets you where you want to go.

5. Reluctance to take losses. This is the reverse side of panic selling. We refuse to sell because that seals our doom. We can’t help believing that a stock is worth the price we paid for it, so we hang on to losers, waiting for them to “come back.” As long as we wait, we have hope. Selling buries hope, which makes us miserable. Antidote: take losses in December, when you can think of them as tax deductions. Or think of the sale as a “swap” for another investment you like better. Or sell just some of the stock today and sell more later if it keeps doing poorly.