Every Investor’s Bedrock Buy

I love mutual funds. Left alone to compound,

they’re the surest way to wealth—but only if you’re

sophisticated enough to keep them simple.

There are two ways of investing: directly, by buying stocks and bonds through a brokerage firm, and indirectly, by buying shares in a mutual fund.

I’m for mutual funds, especially for stock investments. Bonds are a little trickier; sometimes you should go for individual bonds instead. But for long-term growth, a well-chosen stock fund will serve you better than any other financial investment. After a collapse like the one in 2008 to 2009, you might have sworn off funds forever, but it wasn’t the funds’ fault, and they’ll be back. Stocks had near-death experiences in 1929–32 (down 84 percent), 2000–02 (down 45 percent), and 1972–74 (down 42 percent). In retrospect, those were all good periods to buy. The 2008–09 trough will be too.

A mutual fund is an investment pool. You and thousands of other people put money into the pool, which a manager invests in a wide variety of securities. You’ll find U.S. stock funds, bond funds, money market funds, international stock funds, commodity funds, real estate funds—literally something for everyone. There are even funds for people who don’t want to bother picking funds. You own a share of all the securities in the pool.

1. You can buy an index fund. Your investments are guaranteed to do as well as the market, minus fees—a promise that no other investment can make. When planners forecast the size of your retirement pot, they use “market” returns as your hoped-for gain. Only in an index fund (page 745) can you be sure of getting those long-term returns.

2. You can pick the level of market risk that you want to take: conservative, aggressive, or in the middle. By contrast, when you buy your own stocks, you generally have no idea how risky your total investment position is. That is, until the market drops.

3. You share in the fortunes of a large number of securities rather than owning just a few. If one stock in your fund goes bad, it doesn’t endanger your whole portfolio. When you buy individual stocks, you’re not diversified enough.

4. You can participate in the stock market’s long-term gains, or the gains you expect in a particular industry, without having to think about which individual stocks to buy. Your mutual fund does that for you.

5. You can automatically reinvest your dividends and capital gains. Steady compounding doubles and redoubles your returns over time.

6. You can get full-time money management if you want a fund that tries to beat the market. I don’t recommend this type of fund because managers so often come up short. But fund managers do better than stockbrokers or commission-based financial planners, whose job is to sell stuff, not to manage your money. Increasingly, brokers are simply selling mutual funds or their equivalent at a higher price than you’d pay if you bought one on your own.

What about them? Your neighbors who buy stocks would be lucky if they made a killing 1 time out of 20. In some years, they’ve probably done it more often—but everyone is a genius when the market is steaming up. Even in good years, your neighbors accumulate losers and mediocrities (which they don’t mention). Counting losers as well as winners, I very much doubt that they do as well as the average mutual fund, especially if they don’t reinvest all their dividends and capital gains. On the downside, an individual stock portfolio might drop by far more than the average mutual fund. Think General Electric, AIG, and Citigroup.

Some investors enjoy the sport of buying stocks directly. But I’d buy mutual funds first. And even if I played around with stocks, I’d use funds for my important, life-changing money.

Most investors today own traditional, open-end mutual funds—the type of investment you’ve known for decades. Closed-end funds (page 788) are for traders. The newer exchange-traded funds (ETFs—page 785) are a great improvement over the open-end funds sold by brokers but not necessarily better for people who choose their own no-load funds (funds without sales charges).

These are the traditional mutual funds that most people buy. The fund sells you shares, either directly—online or by mail—or through a brokerage account. Shares are priced at the fund’s net asset value (NAV). That’s the current value of all the securities the fund owns, minus liabilities, divided by the number of shares outstanding. Share prices rise or fall every business day. Each day’s NAV is based on prices toward the end of the day—usually 3:00 p.m. or 4:00 p.m., Eastern time. You can buy and sell shares whenever you want, at that day’s NAV.

Every year, investors receive a pro rata share of the dividends earned by their fund plus any net profits from the sale of securities. This income can be taken in cash or reinvested automatically in more fund shares. Payouts are called distributions and may be paid monthly, quarterly, or annually. (Fixed-income funds may declare distributions daily, even though they pay out on monthly or quarterly schedules.)

An open-end fund provides you with a prospectus, updated annually. It tells you what types of investments the fund makes, discusses the risks, presents the fund’s past performance, lays out the fees, and explains the rules for buying and selling shares. Fund managers also send their shareholders semiannual and annual performance reports with a letter explaining why the fund behaved as it did.

Most open-end mutual funds are actively managed, meaning that individual analysts pick the securities that the fund owns. The fund compares itself with a benchmark—a particular market index that best represents the types of securities it buys. For example, a fund that buys large companies will benchmark itself against Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, which represents how well large companies perform. An active manager’s success depends on whether he or she can exceed that benchmark with any consistency.

Passively managed, or index, funds don’t depend on managers to pick stocks. They’re designed to duplicate the performance of a particular index, such as the S&P 500 or the Wilshire 5000 index of smaller stocks. Index funds own all the stocks (or a representative sampling of the stocks) in the particular index they follow. Their manager’s job is to handle the buying and selling so that the fund price and its index stay on track. Effectively, index funds become the benchmarks that actively managed funds have to beat, in order to claim success.

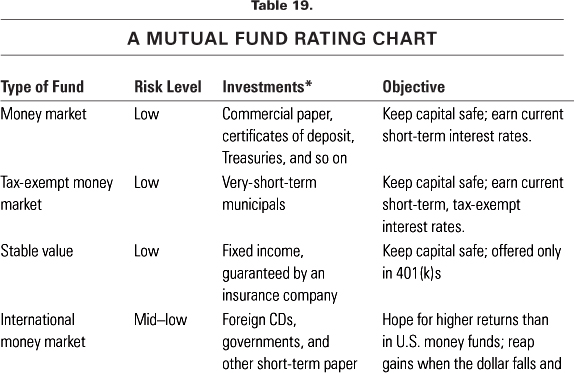

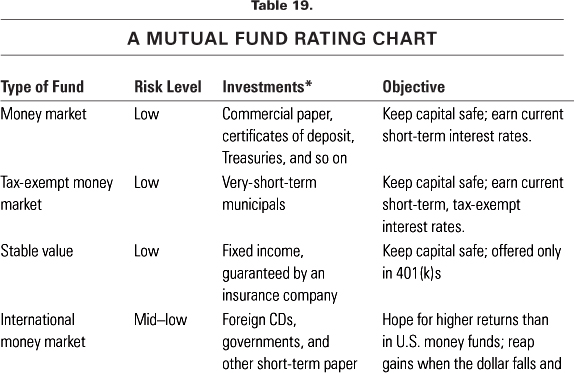

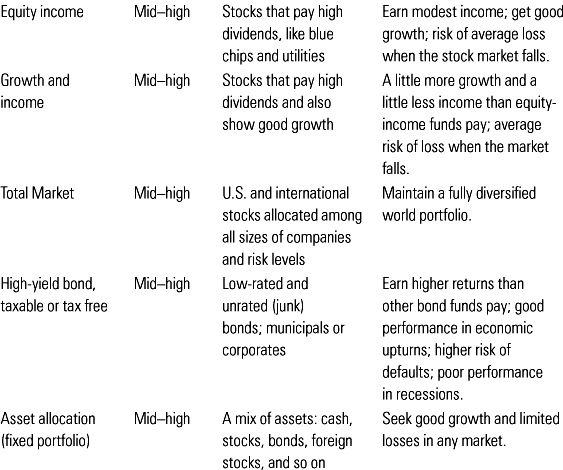

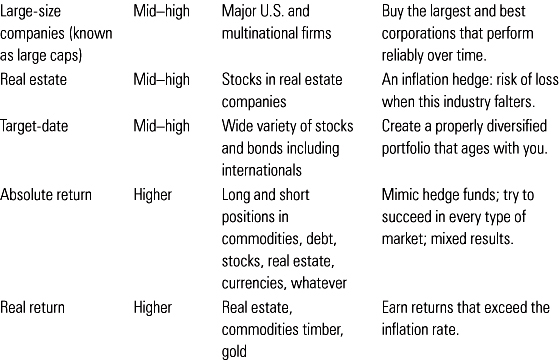

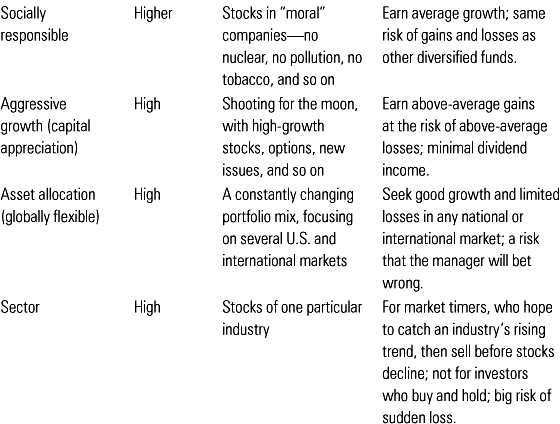

Here’s a summary of the kinds of funds available, what they invest in, and what they hope to achieve. Note that they may or may not achieve their goals. I’ve started with the funds that carry the least market risk and, roughly speaking, advanced to those that carry the most risk. Use this list as a quick reference to check on the funds you read about. There are many other types of funds, with narrower objectives, but this at least gives you a look at the landscape. For a more detailed discussion of stock and bond funds, see chapters 24 and 25.

You can win at the stock-picking game by deciding not to play at all. Do it by buying an index fund, also called a passively managed fund. Indexers don’t try to beat the market. They don’t break their heads on stock analysis or economic trends. They don’t scour the Web for the names of “genius” managers who are beating the market. They simply buy the stocks (or a representative selection of the stocks) that track a particular market index. With just a few index funds, you can create your own well-diversified portfolio, giving you growth for the future without exposing yourself to extra risk. Here’s how index funds work and why they’re so good:

To start with, what’s an index? It’s a way of measuring changes in price. You’re probably familiar with the consumer price index, which tells you how fast or slowly prices are rising for consumer goods. A stock market index tells you how fast stock prices are moving and whether they’re going up or down. Was it a happy day in the market, a ho-hum day, or a rotten day? The index knows.

The stock market index that you hear about the most is the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The Dow covers 30 large American companies. The change in their average price shows whether the market was strong or weak that day. When the Dow rises, the talking heads on TV will intone that “stocks went up.” When it falls, “stocks went down.”

If you’re an investor, however, other indexes matter more. The most important is Standard & Poor’s 500 (the S&P 500, for short), a composite of 500 leading U.S. companies. It contains many more stocks than the Dow, which makes it a superior way of tracking how well America’s larger companies perform over time. The Wilshire 5000 index tracks the performance of smaller stocks as well as larger ones, so you get a picture of the market, overall. Other indexes track the performance of bond prices, international stocks, and the stocks of certain industries such as real estate. You can see at a glance whether their prices are up, down, or flat.

What’s an index mutual fund? It’s an investment designed to copy the performance of a particular market index. The best example is the S&P 500. An S&P index fund owns the stocks of those 500 companies. When the index rises 5 percent, an S&P 500 index mutual fund will also rise 5 percent, minus whatever the manager charges in costs. When you buy this fund, your money is invested in the average performance of America’s major corporations.

There are index funds for every market you can think of. They’re basically run by computer, which adjusts the fund’s investments to match the way the market changed that day. Each fund does as well as its particular market overall, minus costs.

How are index funds different from other mutual funds? Most other mutual funds are run by people, not by computer. They’re called actively managed funds because managers decide which stocks or bonds to hold. One manager may love Cisco Systems, so he buys a lot of it. Another may load up on Procter & Gamble, which she thinks will do even better. Only in hindsight will you know which one was right.

Professionals try to “beat the market”—meaning beat the returns on index funds. Believing (or hoping) they’ll succeed, investors pay them higher fees. That feels like the right way to invest. You assume that the people who study the market full-time will produce superior results. But it’s all mystique. I’ve run many, many long-term performance comparisons between index funds and the managed funds that compete with them. At most, I’ve found three or four individual managers—out of thousands—who beat the indexers over ten years.

You don’t have to monitor your index funds. They don’t need oversight the way that managed funds do. The manager won’t change; the investment committee won’t make a disastrous asset-allocation decision. Once you’ve settled on your asset-allocation plan, you can invest and forget.

What happens to index funds when the market drops? Index funds fall when the market does. Managed funds do too. But index funds never sink further than the market, as so many managed growth funds and emerging-market funds did during the long collapse of 2000 through 2002 and again in 2007 to 2009. The way to reduce your losses during the months when stocks turn down is not to look for a manager who will predict the downturn and outsmart it. That’s a bad bet, as the record shows. Instead, own bond funds as well as stock funds, to provide some stability when bear markets strike.

Can managed mutual funds beat index funds? They can, but most of them don’t. It’s hard to beat the performance of the total market over time. A particular fund may do better than the index for three years or even five years. When you read that the Super Bucks Fund has been rising by 30 percent in years when the market in general just poked along, you may rush to buy. But Super Bucks will almost certainly fall behind the market over the following three or five years—often by a lot. It soared because it happened to focus on an industry that suddenly got hot: telecom, energy, banks, whatever. When those stocks cool down, the fund will fall. With rare exceptions, top funds don’t stay on top, even with a talented manager at the helm. When you average their good years with their bad ones, they usually lag.

Countless studies have proved that point. Vanguard’s low-cost S&P 500 fund, for example, has beaten the average big-stock manager decisively over 10-year, 15-year, and 20-year periods. Over some 5-year stretches, the S&P fund runs toward the middle of the pack, but once you reach 10 years, it usually moves to the upper quarter or higher. Remember, investing is a game of odds. You’re not aiming for the top fund every year—that’s an impossible goal. To be a winner, you simply need a fund that runs well above the average manager over the long term. That’s what you can count on an index fund to do.

A few active managers have beaten the S&P over longer periods, even up to 15 years. But there’s no way of spotting those outperformers in advance. The mutual fund you decide to buy (because it’s hot today) will probably not be the one that tops the scoreboard a decade from now. What’s more, the winners beat the indexes by no more than 1 percentage point or so, on average, while the multitude of losers underperform by a lot. Your drive to beat the market makes it likely that you’ll fall behind.

One of my favorite studies* took the 15 largest actively managed stock funds of 1999 and compared their actual four-and-a-half-year performance with how they’d have done if their managers had hibernated over that period of time. You have probably guessed the result already: in 11 of those funds, the stocks that were owned in 1999 outperformed the stocks that the managers replaced them with. Instead of adding value, most of the managers subtracted it! A 2007 study concluded that investors, including institutions, spend around $100 billion a year trying to beat the market (counting fund fees, management costs, and transaction costs)—and don’t.

In theory, active managers have a better chance of outperforming the indexes in certain niches, such as small-company stocks or developing countries. But over 10 years, that hasn’t worked out either.

Why do active money managers lose, given all their resources and expertise? First, they can’t guess—consistently—which stocks will beat the market. Second, they’re constantly trading stocks, which runs up brokerage expenses. Trading might cost the fund up to 2.5 percent a year, which directly reduces your return. Third, they charge high fees. Counting trading and management expenses, an actively managed fund might have to do 3 or 4 percent better than the index, just to cover costs. Finally, their trading racks up taxable capital gains—another cost, if you hold the fund in a taxable account.

You hope that active managers will beat the market, which is why you pay their fees. But in most years, you’re paying them to miss! To be worth your time, a manager has to do well enough to match the investment return you’d get from an index fund, plus cover his or her extra costs, plus cover the extra taxes that result from trading, plus give you a higher return on your money. Not very likely, even if he or she has superior stock-picking skill. Over time, you’ll almost certainly beat them with a low-cost index fund.

If index funds usually beat managed funds, how come investors keep giving managed funds their money? Lots of reasons. The money managers talk a good game. They’re the experts. You read admiring stories about them in personal finance magazines and online investment blogs—always the ones with terrific recent records (recent losers don’t get interviewed). Managed funds advertise “top performance,” and advertising works. You can’t help believing that today’s best funds will stay on top—the continuing triumph of hope over experience. Everyone else buys managed funds, and you think they must know something. They’re the funds that stockbrokers and most financial planners sell. When your hot fund cools, you assume that you merely made a wrong pick and should look for another, better fund. That’s what the experts say to do.

Money managers and financial salespeople dismiss index funds. They remind you that indexing gives you “average” performance, and who wants to be just average? You want to beat the average, right? But most managed funds don’t beat the average over time, even though they claim they can. Think about Chico Marx in Duck Soup, saying, “Who are you going to believe, me or your own eyes?”

Believe your own eyes. The research on index funds is right.

Besides, what does “average” market performance really mean? In the normal world, average means “middle” (ugh, probably mediocre). But not in the investing world. When you’re looking at market performance, “average” is actually “high.” The stock market average is like par in golf—the score that only the best players get. A few golfers beat par, but most fall short. Money managers can sometimes beat the market over short terms, but over the long term, most fall short. If your investment performance matches the market average, you’re up there with the very best.

Indexing can get frustrating if you watch the market all the time. You’ll keep seeing funds that do better, and you’ll think you should be buying them instead. There are periods when a third or more of the managed funds may be ahead. But decades of data prove that the market is hard to beat. The funds that outperformed during the past five years will be different from the winners in the next five years. If you keep trying to guess the winners, you’ll keep making mistakes (studies show this, too). Besides, you’re busy! You want to ignore your investments while you live your life. In 20 or 30 years, you want to wake up, look at the size of your retirement fund, and say, “Wow.” Indexing is a wow.*

If you’d like to join a chat room full of ardent indexers, go to the site run by Bogleheads.org (www.bogleheads.com), named for John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, the first fund company to offer index funds to the general public. It’s an education in itself. For information on the leading index funds, see page 850.

Index funds will do that, of course. But did you notice that actively managed mutual funds collapsed as well? In theory, managed funds should do better when the stock market drops because their genius managers will get you out in time. Ahem. In practice, the majority of them do much worse. The proper hedge against the dangers of the market isn’t to shift to a managed fund. It’s to balance your stock investments with bonds and cash, so you never have everything at risk. That’s what chapter 21 is all about.

In general, there are three types of indexing strategies:

1. Classic index funds. These are the original funds and the type that most people buy. They follow indexes that are weighted by market capitalization.* In market cap indexes, each stock affects the index price in proportion to its market value. For example, take the oil stocks in the S&P 500. If they’re popular and highly priced, they will carry more weight than less popular stocks. Index investors will be proportionately more invested in oils than in other industries. When the oils lose favor, their weight in the index will decline and so will that portion of your index investment. Other portions of the index—say, chemicals or pharmaceuticals—will rise to take their place. Almost all of the open-end index funds are based on market cap indexes. They reflect the average return on the money invested in that particular market.

Critics say that the classic index fund forces you to overinvest in high-priced stocks and underinvest in the lower priced stocks that are better bets. For that reason, they’ve structured new types of indexes that they think will yield superior returns.

2. Fundamental index funds. This is the group that’s getting the most attention. Fundamental indexes are constructed with stocks that meet specific tests of operating value—for example, cash dividend payments, cash flow, total sales, and stock price compared with the company’s book value. Such measures favor smaller companies and stocks with low prices relative to earnings (called “value stocks”). Historically, these two classes of stocks have often (but not always) outperformed other types of stocks, although they carry more market risk.

The fundamental indexes, known as the FTSE RAFI series, track various types of U.S. and international stocks. You invest through exchange-traded funds (ETFs—page 785). They don’t follow the market as a whole, the way classic market cap indexes do. Instead, they’re an investment strategy, tracking the classes of stocks that the sponsors of the indexes think will do the best. And maybe they will, but only time will tell.

3. Dividend index funds. These indexes were built by analysts who believe that dividend-paying stocks will outperform the market over the long run. You invest through ETFs, sponsored principally by the investment company Wisdom Tree. Evidence for the possible outperformance of dividend stocks isn’t as strong as the evidence for the FTSE RAFI fundamental indexes.

The ETFs that track these new indexes have to buy and sell shares more often than traditional index funds do, in order to maintain a portfolio that meets the investment parameters. As a result, investors pay higher transaction costs and may receive more taxable capital gains than if they chose a traditional open-end market cap fund.

Let’s say you’ve bought my story and will use index funds for your core investing. But you want to invest at least some of your money in actively managed open-end funds—hoping to conjure up one of those wizards who might outperform. Here’s how you go about it:

1. Read up. Get some specialized books on fund investing that will carry you past what you’re learning here. The New Commonsense Guide to Mutual Funds by Mary Rowland gives you a quick roundup of investment tips. For a clear-eyed discussion of mutual funds that barbecues herds of sacred cows, pick up Common Sense Mutual Funds by John Bogle, the brilliant founder of the Vanguard funds.

2. Understand the jargon. A growth fund looks for stocks whose earnings are rising rapidly. A value fund looks for companies that have had problems (temporary ones) and whose stock prices have been beaten down. A blended fund buys both types. Cap is short for capitalization, which refers to company size. Large-cap stocks are big companies. There are mid-caps, small-caps, and micro-caps. As a group, small caps are riskier than large caps.

A price/earnings ratio compares the price of the stock with the company’s earnings (usually, earnings over the past year). High P/E ratios (say, over 25) go with stocks and funds that are highly priced relative to earnings; a 15 P/E ratio is about average; a 10 P/E ratio is low—suitable for a value stock or a market in a mess. For more on P/E ratios, see page 873.

A market timer is someone who buys and sells shares based on a short-term forecast of what the market is going to do. If you think prices will rise, you buy. If you think they’ll fall, you sell, hold the money in cash, and wait until you expect prices to go up again. As a way of making money, market timing almost never works. You’re wrong more often than you’re right.

A fund with alpha has done better than the market (that is, better than the particular market that it uses as a benchmark). Managers or strategies that outperform are said to add alpha.

A fund’s beta measures how fast it rises and falls (its volatility) compared with the market. Generally, a fund with a beta higher than 1 is considered higher risk. A beta lower than 1 is lower risk. In theory, a high-beta fund should produce higher returns (note the word should).

The measures of any fund’s alpha and beta aren’t sure things. They change with time and shouldn’t be used to forecast results. But the concepts are thrown around a lot, so you need to know what they mean.

3. Settle on an asset allocation. Decide how to diversify your assets, based on what you concluded from chapter 21. A reasonable mix would be large U.S. stocks, small U.S. stocks, international stocks, emerging-market stocks, and intermediate-term bonds. You can buy them in the form of index funds as well as in managed funds. Real estate stocks are included in U.S. index funds and will probably be in diversified managed funds too. So buy a separate real estate fund only if you want to make a bigger bet on that particular type of investment. You have not diversified if you buy three aggressive-growth funds. They may own different companies, but they’ll all soar or plunge together. Quantity doesn’t mean you’re diversified, either, because the funds probably overlap. You can cover all the bases mentioned in this paragraph with just five funds. Seven would be plenty. As you will see, even seven good managers can be hard to find.

4. Go no-load. When you’re picking funds yourself, stick with those without loads (sales charges): no front-end load, back-end load, or level load (page 766). All things being equal, you’ll do better in no-loads because none of your money goes for sales commissions. No-loads also tend to have lower annual expenses than load funds do. Some leading no-load families include Dodge & Cox Funds, Fidelity, Harbor Fund, Longleaf Partners Funds, Oakmark Funds, T. Rowe Price, and Vanguard.

If your money is being managed by a fee-only financial planner, he or she will probably use no-load funds too. Planners usually charge 1 percent or less on top of the fees the mutual funds charge.

5. Go for seasoning. Don’t buy brand-new funds. You have no idea how well they’ll perform over the long term, even if the manager had a good track record with other funds. New funds often start with gorgeous records—not because they’re in the hands of a wizard but because of the way that mutual funds are developed. A company may start a dozen funds to see how they go. Invariably, one or two will do well over the incubation period. Those are the ones that are subsequently offered to the public, at which point they may turn into very different animals. New funds are also started to catch investing fads—real estate, Internet companies, gold. It’s proof positive that stock prices in that sector are already high.

6. Discover the many research tools that are readily at hand. Here’s where you start developing short lists of potential buys—three or four funds in each of the asset categories for which you’re aiming. Good information sources include:

• Morningstar.com—the leading source of information for both traditional mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (page 785). To find a fund, enter its ticker symbol into Morningstar’s Search box. You’ll get a free “Snapshot,” containing, among other things, the fund’s objectives, investment style, fees and expenses, past-performance stats going back as far as 10 years, tax-adjusted returns, SEC filings, technical measures such as alpha and beta, and its relative attractiveness to investors (the “star” rating—see a warning, below). Another way of getting to the Snapshot is to type the fund’s name into a search engine and follow the Morningstar link. If you don’t have a fund in mind, Morningstar offers lists of recent high performers for you to rummage through.

If you take a premium subscription to Morningstar, you’ll get reams of additional data, analysts’ opinions, fund search screens, asset allocation tools, newsletters, and access to a valuable tool called “Portfolio X-Ray.” When you enter all your mutual funds into the X-Ray, it will tell you how much their holdings overlap each other. You may be less diversified than you think.

• The performance, “best-buy” lists, tips, and news coverage found on the Web sites of the following magazines: Forbes (www.forbes.com), BusinessWeek (www.businessweek.com), Kiplinger’s Personal Finance (www.kiplinger.com), and Money (money.cnn.com) They recommend different funds because they make different evaluations, but any of these lists will do. Like all managed funds, these may or may not beat the market (usually not).

• FundAlarm.com, a fun site to read. It lists the mutual funds you ought to consider selling, called 3-Alarm Funds, and provides some selling rules.

You’ll also find potential “sell” flags at Morningstar. Its mutual fund Snapshots shows “flow data”—money going into the fund (new purchases) and money coming out (redemptions). If redemptions exceed new purchases, the manager will have to sell shares and won’t have new money to invest in better ideas. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the fund’s price will drop. The manager and the new purchases may recover. But it’s a warning sign.

• The Web sites of popular mutual fund groups such as Fidelity, Vanguard, and T. Rowe Price. They provide tons of investor education and advice, as well as information on their various funds.

• The Web site of a recommended fund. Look at its investment objectives to see if they mesh with yours. Call up the most recent annual report and read the letter to shareholders to see what the manager thinks about the market and his or her own performance. Does the manager make sense? Do you understand the strategy? Then check the financial parameters: recent performance, average price/earnings ratio of the shares it holds, the percentage of assets held in different industry sectors, the minimum investment required, expenses, and other data.

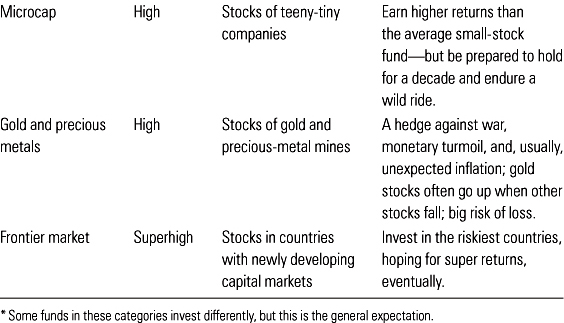

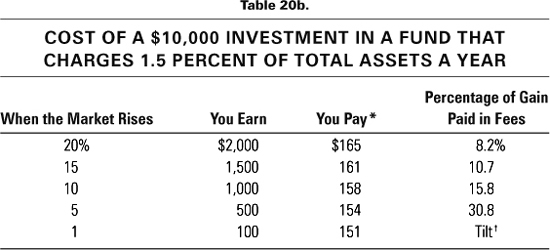

7. Choose funds with low annual expenses. You’ll find a full discussion of expenses on page 764, including the surprising bite that a “mere” 1.5 percent a year subtracts from your investment gains. (Hint: you lose a lot more than 1.5 percent.) Index funds from no-load companies have the lowest costs. To earn his or her fee, any fund manager has to deliver an investment return high enough to cover expenses and outperform a low-cost index fund, not just for a year or two but over a long period of time. That’s a tall order, especially if the fees exceed the averages shown on page 770. (Note, by the way, that not all index funds are low cost. Expensive, broker-sold index funds ought to be outlawed.) At Vanguard, many of the managed funds have beaten their benchmarks over various periods of time, partly because of their low fees.

8. Check the minimum investment. Most funds require $1,000 to $3,000 to open an account. A few hold out for $10,000 and up. You can sometimes open an Individual Retirement Account for less. Once you’ve become a shareholder, funds might accept additional investments of as little as $50 to $100. Some funds, including T. Rowe Price, let you start with $50 a month as long as the money is deducted automatically from your bank account.

9. Look for managers who have been in place for at least five years. Managed mutual funds are run by people, not computers, and you need to know who those people are. Some of them have proven to be more skilled than others. When the lead stock picker leaves a fund, it effectively has no record until the new manager shows what he or she can do. The fund’s Web site will tell you who the manager is and how long he or she has been there. You’re hoping for a wizard (even though, deep in your heart, you know that wizards don’t exist). Tenure isn’t linked directly to performance, but a manager who has been there awhile at least knows something about the research team and understands the fund’s portfolio.

A few well-regarded funds are run by teams. In this case, a change in lead manager may not matter much, as long as he or she has been with the group a long time. When a fund claims to have team management, however, read that section of the prospectus with care. The investment method used by the fund should be clearly spelled out, and most of the team’s major players should have been on board awhile.

A few funds, at families such as Harbor and Vanguard, farm out money to various independent managers. That’s a good way of signing up the industry’s leading lights.

10. Check for consistency of investment style. A fund’s style is defined by the kinds of stocks it invests in. Again, your best source is Morningstar. It prepares “style boxes” for each fund, defining the way the fund behaves. Is it invested primarily in large, medium-size, or small companies? Does its manager lean toward value stocks, growth stocks, or a blend? You want to see consistency (Morningstar shows prior-year style boxes, going back as far as 10 years, at the top of each fund’s detailed Snapshot).

If the fund has drifted into and out of different styles, pass it by. The managers aren’t in control of their strategy or are spinning the public, neither of which is promising. For example, take a high-performance small-stock fund that is now buying mid-caps. It probably got more new cash from investors than it knows what to do with. So it’s being pushed into the mid-cap arena, where it may not fare as well. And take a value fund with a mediocre record. If it buys some growth stocks in a rising market, it may outperform its peers and rise to the top of the value list, which is a cheat. Morningstar fights these games by classifying funds based on the way their securities behave rather than by the type of fund they claim to be.

11. Consider the fund’s size. Its size should be congruent with its investment goals. Small-company funds tend to lose their character once they’ve passed $1 billion in size. Funds specializing in mid-caps can generally handle up to $5 billion. Big-company funds can be any size. As for bond funds, the bigger the better.

Managers sometimes announce that they’re going to close their funds. That’s no time to buy. You’ve effectively been told that the fund has attracted more new money than it can handle, which means that performance may fall off. Reconsider the fund when it opens again, provided that its larger size hasn’t forced the manager to change his or her investment style.

In general, small-stock funds do better than large-stock funds, but not all the time. Sometimes one group outperforms the other; then their records reverse. The data suggest that the outperformance comes from small-stock value funds rather than small stocks in general, so you might consider focusing your small-stock allocation on the value group. Performance depends on the manager, of course—unless you’re in an index fund.

Small-stock funds are more volatile than those that own large stocks. On average, they rise more in good markets, attracting a lot of hot money. They fall more in bad markets, causing trend-following investors to flee. You take more risk in a small-stock fund, hoping to bag a higher return.

12. Avoid funds managed by banks and brokerage houses. They have lousy records, and not just because their fees are typically high. They have major investment banking clients they want to please and initial public offerings to manage. Studies have shown that to win big future fees, banks and brokerage firms may stick their clients’ stocks into their own mutual funds and private investment partnerships, including stocks that aren’t doing well. You can count on banks and brokerage firms to put their own interests first.

13. Look at past performance. This is the tough one. Past performance doesn’t predict future returns, and that’s not just boilerplate. It’s real. So what can you make of the performance data? Can they help you find one of the better funds?

To begin with, your quarry is always a manager, not a particular fund. So the fund’s performance is relevant only if that manager is still there and his or her methods haven’t changed. Otherwise the testing period has to start all over again.

Most investors rely on Morningstar, which rates most of the funds that have been in existence for three years or more. Funds get anywhere from one star (bottom rung) to five stars (tops), based on their past performance adjusted for risk. The categories—internationals, large-caps, real estate funds, and so on—are rated separately, so you see each fund’s performance relative to its peers. A five-star international fund has done better than most other internationals over the rating period. Investors follow ratings slavishly. Most new investments pour into funds with four or five stars. Those are also the funds most widely advertised and promoted on the companies’ Web sites.

Morningstar’s research shows that five-star equity funds, as a group, slightly outperform four-star funds three and five years later. Four-star funds slightly outperform those with three stars, and so on down the line. But the average outperformance is very small—usually just a few tenths of a percent. For example, in a period when five-star U.S. equity funds returned 11.93 percent, the four-star funds returned 11.78 percent, a difference of just 0.15 percent. The one-star funds returned an average of 10.84 percent. Each “star” group has better and worse performers, but the stars can’t tell you which ones they are.

There’s something else interesting about these ratings. Over three and five years, the top-rated funds fall to the middle of the pack. As a group, they start out with five stars and wind up with three stars. That’s consistent with everything else we know. Regardless of tenure, managers who produce positive, risk-adjusted returns for three years are not likely to repeat their performance in subsequent periods. They’re on top when their favorite industries or stocks are hot; then they fall back, and other stock pickers take their place. The next generation of five-star funds could come from anywhere on the list.

So what good are the star ratings? Use them this way:

• One-star funds are less likely to move up, so that’s not the best place to troll for good managers.

• Five-star funds aren’t likely to retain their ranking, so that may not be the best pool to choose from either. If you buy, look beyond the stars.

• Consider the three-star and four-star groups. A three-star manager with five stars in his or her past might cycle back up when those types of stocks gain favor again.

• Low-cost funds get better star ratings than high-cost funds. That’s probably because the high-cost funds take on more investment risk. They need higher returns to cover their expenses and still be competitive. Their strategy might be successful, but it’s also more likely to fail. That’s what risk is all about.

• The best place to start would be a higher-rated fund with low costs. Low costs are still the best predictor of long-term performance, Morningstar says.

14. Look at the fund’s cumulative record and deconstruct it. The fund’s Web page and its Morningstar Snapshot give you the average annual returns over five years, three years, and year to date, compared with an appropriate market benchmark. But even though it’s nice to have beaten the market, that’s not nearly enough. Maybe the manager had four poor years plus one huge year, thanks to some lucky stocks that put him ahead. So check the year-by-year performance—again, you’ll find it on Morningstar. You’d like to see consistency compared with the benchmark, not wild ups and downs.

15. Look at how well the manager performed compared with his or her peers. Here again, Morningstar can help. The Snapshot shows the fund’s performance relative to other funds in its broad category, as well as to the general market. Another great source is FundAlarm.com, a site that focuses on which funds are candidates for trash. Click on your fund, and you’ll see how the manager stands, compared with the fund’s most suitable benchmark, over the past one, three, and five years.

You can’t expect a manager to beat the market all the time, but he or she should do well compared with other managers buying the same kinds of stocks. Skip any fund that hasn’t kept up with, or exceeded, the average performance of its peer group for at least three years.

16. Check the fund’s performance in down markets. For recent markets, that means 2000–2002 and 2008–2009

In bear markets, some funds drop further than the general market average and then spring back: small-cap growth funds, for example. Others go down less but may not turn up as fast—more descriptive of value funds. Think about which type of fund would make you happier. Daring investors love volatility; sharply declining markets let them buy funds cheap. Conservative investors hate excessive drops in price; they might be scared into selling near the bottom, which costs them their chance to recover their loss. Over the long term, supervolatile funds generally don’t perform as well as steadier ones. They lose so much in down markets that it’s harder for them to recover their previous peaks.

Probably not. Investors usually don’t do as well as the mutual funds they buy. The reason is simple. You buy, or add to, successful funds after they’ve started zooming in value, not before. You sell during mediocre years, before the fund picks up again. On a buy-and-hold basis, the fund’s past performance could be fine. But because of the way you timed your investments, you might show a loss.

How far behind do individuals fall? You can find out at Morningstar.com, which keeps track of average investor returns. Go to Morningstar’s home page and enter the name of a fund in the “Quotes” box. When the fund page comes up, click on “Total Returns” to get its performance record. You’ll then see a tab for “Investor Returns.” Click there to find out how well (or poorly) a typical investor did.

Investors have fared the worst in volatile funds where prices zoom and dip. One example would be the technology sector. In a particular 10-year period when those funds grew at an annual 6.4 percent, their average investor was losing 4.2 percent. Investors have fared the best in conservative funds, where returns are steadier. This group includes the giant, well-diversified stock funds as well as funds that buy both stocks and bonds.

What’s the lesson? If you seek the thrill of aggressive funds, you should be prepared to stick with them during their poor years too. Otherwise you’re more apt to lose money than gain it. Investors who will sell after a couple of poor years should choose more conservative funds. Over the long term, you’ll make more money in a fund that you can buy and hold.

A contrarian’s starting place. Hunt for managers of lower-cost funds who have done well against their peers in the past and whose investment style is currently cool, not hot. They’ve probably lagged the market for two or three years. The types of stocks they buy have been out of favor for a while but might be ready to come back.

Don’t be driven by fund envy. Every month the personal finance magazines and Web sites heap praises on the Fabuloso Funds of the Moment. Unfortunately, they’re almost never funds you own. If you buy them, they’ll usually shine for a while, then fall off. That’s because it’s not skill that puts most of these fund managers on top. Their stocks or investment style just happens to be in vogue. When styles change, their stars will dim, and the magazines will fall in love with another set of funds. Screen a Fabuloso Fund just the way you’d screen any other. Magazine editors have to produce exciting new reading matter every month and don’t know any more about the future than you do.

Why would you bother? A new fund is a huge risk. Its manager may have hit home runs at his or her last fund, but these are new conditions and who knows how long it will take for the portfolio to shake down?

There are some possible advantages. A new stock fund starts small, so its winning picks will have more impact than they would on a bigger fund (ditto its losing picks, of course). The fund has a flow of fresh cash to leverage the manager’s best ideas. In bull markets, these funds often have pretty good opening months.

Still, performance is a question mark. Unless you’ve screened the manager at his or her last position and think you have a wizard, stick with seasoned funds whose long-term records are spread out for all to see (page 763).

Screen it as carefully as you would any other fund. Bank funds aren’t safer or better. They are not government insured. They’re not cheaper or smarter or more attuned to small investors. You can lose money; these are not CDs. They’re just mutual funds with sales charges, competing for your money along with all the rest.

Stocks went exactly nowhere after the tech bubble burst in January 2000. Correction: large-company stocks went down, then clawed their way back to a little above their previous peaks and then dropped again. Tech stocks never reached their previous peak. Real estate stocks bubbled and broke. Investors started talking about alternatives to stocks: commodities, currency futures, gold, and various hedge fund strategies.

A hedge fund supposedly protects you from market declines. Here are some of the strategies being offered to stunned and unhappy stock investors:

Market-neutral funds. These funds include long positions in stocks (where you profit if prices rise) and short positions (where you profit if prices fall). The two types of positions should be of roughly equal value and invested in similar industries. If the stock market rises, the longs are supposed to produce more gains than the losses you take on your shorts. If the market falls, the shorts are supposed to earn more than you lose on your longs. Some market-neutral funds exploit small technical anomalies among stocks, making quick and constant trades. In either case, the managers aim to make money in any market, with returns exceeding the Treasury bill rate.

Absolute-return funds. By “absolute,” they mean that they’re managed to produce returns that, specifically, are not linked to the stock market in general. They’re the anti–index funds. They’re managed to decline less in bad markets by limiting risk. In return for that protection, you earn less in good markets. Absolute-return funds use a variety of hedge fund strategies, including long/short positions, commodity and currency speculations, international investments, real estate, managed futures, cash, bonds, and assorted derivatives. Some of these funds are marketed as being able to make money in any market, which I’d call deceptive and delusive. Ditto for funds that appear to promise specific returns over a designated time period. The proper function of these funds (if managed well) is to fall less than stocks do when the market declines.

Synthetic absolute-return funds. These are sold in the form of ETFs. They track average hedge fund performance at much lower cost than you’d pay to be in a fund itself. Two such: the Goldman Sachs Absolute Return Tracker fund and Natixis ASG Global Alternatives fund.

What’s the record on these funds? So far, decidedly mixed.

At this writing, market neutral funds have done worse than Treasury bills and ultra-short-term bond funds. Even if they did a tad better from time to time, I have no idea why you’d want to pay for a complicated and expensive investment that aspires to the same returns you’d get from something simple and safe. My opinion: skip them.

Absolute-return funds, on average, lost less during the 2007–2009 carnage than all-stock funds. In that respect, they fulfilled their charter. Still, not all strategies worked, and expenses can top 4 percent. Hundreds of hedge funds collapsed during the market crash. For success, you depend absolutely on the manager’s skill, which, as a practical matter, you and I can’t figure out. A few of them are supergood (for a while, at least) while the rest just run up trading costs and expenses. If you want a diversification into an absolute-return fund, buy the ETFs of one of the synthetic funds that copy the sector’s average performance. Unlike the funds, ETFs carry reasonable costs.

Commodity prices normally move on a different track from the prices of stocks and bonds, which is a plus for a diversified portfolio. At this writing, they’re down. In recessions, demand for commodities falls. With recovery, however, they’ll pick up again. As a diversifier, they’re worth maybe 5 percent of the money that you normally allocate to equities.

The easiest way to invest is through an exchange-traded fund (page 785). Commodity ETFs buy futures (page 963), not the commodities themselves. They also buy Treasuries and borrow against them for leverage. These complications make them expensive to run, so fees are higher than you’d normally find in ETFs. But they’re cheaper by far than commodity mutual funds, especially when you consider sales commissions. For information on appropriate ETFs, see page 852.

Read the prospectus before you buy! Sales literature is fine, but it takes a prospectus to clue you in to the fund’s costs and risks. When investing, there’s no avoiding risks, but you should understand the ones that you’re about to take.

Prospectuses for the widely sold no-load mutual funds have become remarkably clear, so there’s no reason to shy away from them. They’re well presented and written in plain English. Sit down with a pen and underline the important points as you read. That helps you focus. Most of the key things you need to know are in early pages. Toward the end of the prospectus, you’ll get more detailed information about fees, taxes, and all the special rules that affect buying and selling. For example, many no-load funds apply frequent trading limitations: if you sell (say, to nail down a year-end tax loss), you may not be able to buy again for 30 or 60 days. Most load funds, by contrast, are happy to have you trade—it’s a commission to the broker each time.

Also, ask for (or download) the Statement of Additional Information (SAI). That’s part B of the prospectus. Most of the data there is probably not your cup of tea. But you might be interested in the list of directors and officers, their compensation, and whether the manager is investing in the fund. You want the manager to have a substantial amount of skin in the game (at least $500,000).

If a fund is still offering an old-style, clear-as-mud prospectus, it doesn’t care much about its retail investors. You should take the hint. A complex or technical prospectus also suggests that the fund uses complicated investment techniques that entail more risk than you care to take. If you don’t understand the explanations, this is definitely not the fund for you.

Mutual funds are allowed to give you a plain-English summary prospectus—just a few pages disclosing key facts: investment objectives, costs, risks, performance, investment advisers, and the top 10 holdings. Each fund will have to deliver the information in the same order, making it easier for you to compare them. For reaching an investment decision, the summaries will probably be enough. Still, you should get the full prospectus too, in case there’s something about the fees or transaction rules that you want to look up or if a question ever arises. The summaries and the prospectus can be mailed, if you want them, or downloaded from the fund’s Web site. Keep the original prospectus, along with the SAI, permanently on file, or bookmark them on your computer for future reference. You’ll get a new prospectus every year to bring you up to date. If the fund makes any changes in its investment methods or objectives, you’ll be notified separately.

Investors also get annual reports, which are also posted on the fund’s Web site. Always read the fund manager’s letter in the front of the report before you invest. It discusses the fund’s performance during the previous year. The best managers are very explicit about what happened and why. I’d suspect a fund that gave me fog or boilerplate. Many no-load funds post previous reports, so you can track the manager’s thinking over several years.

Prospectuses for no-load funds are available on the company’s Web site too. Some load funds put up prospectuses, but many of them don’t want you to look. They put up only sales material and tell you to call a broker for more information. If you do, ask for the prospectus and the most recent annual report before you buy. No matter how hard he or she pushes, look at the prospectus first and run its costs through the Fund Analyzer at www.finra.com (page 769).

When you read a prospectus, here’s what you’re looking for:

Read this section with great attention. What you see is (usually) what you get. Study the fund’s objectives in light of the ideal portfolio you have designed for yourself. Will this fund fit in? Does it buy small stocks, invest for growth, emphasize income? Does the manager try to time the market, and is that what you want? If the fund has two objectives—say, income and growth—it won’t maximize either one of them. But that mixed objective may be exactly what you want.

Some prospectuses speak for several funds, each with a different investment objective. Make sure you’re reading about the one you want.

This section tells you how the fund expects to meet its goals. What will it buy? Just as important, what won’t it buy? Some funds stuff everything into this section, to leave its manager free to go in any direction he or she chooses. That’s not a good sign. Your intent is to buy a particular type of investment, not give its manager a blank check. A useful fund defines its style and stays within those limits.

To help you understand its investments, the fund may include little primers on such things as how the bond markets work and what options or derivatives are. Small growth funds often get their performance kick by investing in high-risk initial public offerings—something buyers often aren’t aware of.

On the front of the prospectus, READ ANY SENTENCES SET IN CAPITAL LETTERS. That’s usually a red alert. It might say, INVESTING IN THE SHARES INVOLVES SIGNIFICANT RISKS. Or INVESTORS ARE SUBJECT TO SUBSTANTIAL CHARGES FOR MANAGEMENT. Or whatever. A sentence in capital letters tells you there might be trouble or cost. The risks will be covered in greater detail inside the prospectus—a section you shouldn’t fail to read. If you lose money and complain, you can count on the lawyers for the fund to say “We told you so.”

You’ll see average annual returns for 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years (or since inception, if the fund hasn’t been around that long). But these numbers don’t tell you much. They’re not compared with a standard market index, so you can’t tell whether the fund has done better or worse than the market as a whole. To see the annual returns compared with an index, you have to look in the annual report, which—for no-load funds—is viewable on the Web site.

There’s one important line in prospectus’ performance table, however. It shows your returns after tax, with taxes figured in the highest bracket. When you’re planning your future, it’s important to work with after-tax returns, so you don’t kid yourself into thinking you’re richer than you are.

There are five types of costs: direct sales commissions (loads), marketing charges (known as 12b-1 fees), money management fees, account maintenance or service fees, and overhead expenses.

No-load funds charge no sales commissions and usually no 12b-1 fees (although occasionally there’s a small fee of 0.25 percent). You buy them directly from the fund company or through a mutual fund supermarket (page 779). Annual money management fees vary from fund to fund. There may be $10 or $20 account fees on small accounts.

Load funds charge sales commissions, 12b-1 fees, overhead expenses, service fees, and, on average, higher money management fees than the noloads do. You buy them through stockbrokers and commission-based financial planners.

The 12b-1 fees, overhead, and money management expenses (but not the sales commission) make up a fund’s expense ratio—the ratio of costs to total net assets—also called the fund’s annual operating expenses. Every investor pays a pro rata share.

As a result of the terrible market performance from 2000 through 2009, investors have been paying more attention to fees. There’s been a general migration to low-fee fund groups by people who choose their own investments.

Fees have stayed high, however, in broker-sold funds. You may think that they don’t amount to much because they’re quoted as a small percentage of your total investment. But when measured against your investment gain, they actually take an enormous bite. In fact, the 2.5 percent you might pay for a broker’s mutual fund advisory account can only be called confiscatory. Even a 1.5 percent fee burdens your returns. In a slow-growing market, only a low-cost fund—charging 0.5 percent or less—keeps you alive. See the proof in the table on page 765. Bond funds need low fees to make any headway at all.

You’ll find the fund’s loads and expense ratios in the fee table in the front of the prospectus. If you look at nothing else, look here. How many of the following costs will you have to pay?

(continued on page 766)

A Front-End Load—an up-front commission paid to the salesperson. It’s assessed on what the fund calls A shares and typically ranges from 4.5 to 5.75 percent. That’s $45 to $55 for every $1,000 you put up, leaving you $955 to $945 to invest. Some funds, plagued by weak sales, are cutting their loads to less than 3 percent.

At any commission level, you get a discount for investing a lot of money at once. The levels where the discount applies are called the break points. For example, the commission might drop to 3.5 percent if you invest $50,000 or $100,000, 2.5 percent for $250,000, and 1.5 percent for $500,000. If you’re going to put up, say, $100,000, but in stages, see if you can file a letter of intent giving you a reduced commission right from the start. When several people in your immediate family invest in the same family of funds, the fund might count everyone’s assets to determine whether each of you has passed the break point.

A Contingent Deferred Sales Load—an exit fee, charged if you drop your fund within a specified number of years. For example, you might pay 6 percent if you sell the first year, 5 percent the second year, and so on. Six full years would have to pass before you could sell your shares without paying a penalty. Some funds assess the exit fee against your original investment. Others assess it against whatever the fund is currently worth, which raises your cost if the market goes up.

Shares with deferred sales charges are generally known as the fund’s B shares. Some salespeople tell B-share customers that they’re buying a no-load because there’s no sales charge up front. That’s a lie. The broker always gets a commission. You simply pay it in other ways—including higher 12b-1 fees (described further on). Before buying, be sure you understand how long you’re going to be locked in.

A Level Load—an annual charge for sales commission and money management combined. Typically, it’s 2 to 2.5 percent of the value of the account. There may also be a 1 percent front-end or back-end fee. Brokers usually call these C shares.

A 12b-1 Fee—an annual fee paid to cover sales expenses, principally the salesperson’s commission for B and C shares but also advertising, marketing, and distribution fees. It ranges from 1 to 1.25 percent and is levied every year, eternally. Some firms, however, reduce it on B shares after five or six years. Load funds are the heaviest users of 12b-1 fees. By definition, a no-load can’t charge a 12b-1 of more than 0.25 percent. A majority of no-loads don’t levy this fee at all.

An Exchange Fee—levied by some fund families when you sell one fund and buy another within the group. It runs between $5 and $25 and is usually the only charge. You should not have to pay a sales load all over again.

A Money Management Fee—charged by every mutual fund, load and no-load, to compensate the managers who run the money.

Transaction Costs—the price of buying and selling securities. These include brokerage fees, market impact costs, and the spread. Market impact is the cost to the fund if a large order to buy pushes up the stock’s price (or if a large order to sell pushes it down). The spread is the difference between a security’s bid and asked price—page 867.

The more a fund manager trades, the higher these internal costs—all of which come out of your pocket. In some cases, trading costs exceed the fund’s expense ratio! On average, they add almost 50 percent to the costs included in the fund’s published expense ratio. That’s another reason why active managers find it hard to beat the market index.

Index funds cost the least to run, because there’s virtually no trading. Next lowest in cost should be U.S. bond funds, then U.S. funds that buy large-company stocks. Funds that buy smaller U.S. companies incur higher transaction expenses because they buy in the NASDAQ and over-the-counter markets, where spreads are wider. Global and international funds, especially those in emerging markets, carry the highest costs of all.

Transaction costs don’t show in the funds’ published list of fees and expenses. They’re paid out of assets as a regular cost of doing business.

Service Fees—placed on smaller accounts. They amount to $10 or $20 a year on accounts smaller than $5,000 or $10,000, depending on the fund. They might be waived if you transact all your business online.

Other Fees—shareholder accounting, franchise tax, start-up fees, account maintenance fees, legal and audit fees, printing, and postage—you name it, someone is charging it.

Waived Fees—Some funds raise their returns and hold down reported costs by temporarily waiving some of their fees. Only the asterisk tells the tale. Say, for example, the prospectus shows an expense ratio of “1.25%*.” Under the asterisk, you might learn that the full fee is 1.8 percent, but the fund manager is taking less for a certain period of time. In the future, the fund will try to recover any fees it waived in the past. When making a buying decision, go by the full fee, even if it isn’t currently being collected. You’ll have to pay it eventually.

Redemption Fees—penalties charged by some no-load funds for selling shares within a short time after buying them, typically three to six months. The fee usually runs between 0.5 and 2 percent and is meant to deter you from using the fund for short-term trading. Trading adds to fund costs and can make it hard for managers to execute their long-term strategies.

Hypothetical Costs in Dollars and Cents—A table in the prospectus discloses what you might pay over 1, 3, 5, and 10 years, in dollars and cents, for every $10,000 invested, assuming an investment gain of 5 percent a year. Stated this way, the expenses look too small to worry about—another reason that high-cost funds get away with noncompetitive charges. Sneak another peek at the tables on page 765 to remind yourself what you’re really paying.

The Published Performance Data You See in Magazines Make Load Funds Look Better Than They Really Are.That’s because those “best buy” lists usually compute performance without deducting the up-front or back-end sales charge. You’re looking at gross returns, not the net to the investor. A load fund may look better before fees, but the no-load may beat it after fees. Morningstar shows returns adjusted for fees and the fund prospectuses do too.

Choosing a Sensible Way to Pay. (1) Buy a no-load. (2) Buy a no-load (yep, I repeated myself). (3) Buy an ETF if you’re dealing with a broker. (4) Very last choice, if you’re dealing with a broker: buy an open-end fund. Broker-sold open-ends offer A, B, or C shares, each type carrying a different level of fees. Here’s what that alphabet is all about:

A shares—You pay an up-front sales commission and a small annual 12b-1 fee. This is usually the cheapest way of buying load funds for the average investor. Over time, what you save on annual fees will more than cover your up-front cost. The up-front commission declines if you are investing large amounts. I ran dozens of comparisons on the Fund Analyzer (page 769), using popular funds. A shares consistently came out on top—sometimes even in the very first year.

A shares—You pay an up-front sales commission and a small annual 12b-1 fee. This is usually the cheapest way of buying load funds for the average investor. Over time, what you save on annual fees will more than cover your up-front cost. The up-front commission declines if you are investing large amounts. I ran dozens of comparisons on the Fund Analyzer (page 769), using popular funds. A shares consistently came out on top—sometimes even in the very first year.

B shares—You don’t pay an up-front commission, but there’s a deferred sales charge if you sell within five or six years. There are no break points, so you don’t get a discount if you’re investing a large amount. You’re charged a higher 12b-1 fee, which may or may not be reduced after five or six years. The dollar cost of a 12b-1 increases as your fund rises in value, so high 12b-1s take extra nips out of your gains. Brokers have sometimes missold B shares by telling customers they’re buying a no-load fund (fat chance at a brokerage house!) or selling them to large investors who should have been given A shares for the lower commission. Some funds have quit selling B shares or sell them only with the approval of a supervisor.

B shares—You don’t pay an up-front commission, but there’s a deferred sales charge if you sell within five or six years. There are no break points, so you don’t get a discount if you’re investing a large amount. You’re charged a higher 12b-1 fee, which may or may not be reduced after five or six years. The dollar cost of a 12b-1 increases as your fund rises in value, so high 12b-1s take extra nips out of your gains. Brokers have sometimes missold B shares by telling customers they’re buying a no-load fund (fat chance at a brokerage house!) or selling them to large investors who should have been given A shares for the lower commission. Some funds have quit selling B shares or sell them only with the approval of a supervisor.

C shares—You pay no front-end or back-end load, but the annual 12b-1 is high and it never declines. For longer-term holders, this is the most expensive way to pay. C shares are cheaper than A shares only if you sell within five years or so, and why would you buy a load fund if you intended to hold for only five years? If you want to trade in and out of mutual funds, go with a no-load or an exchange-traded fund (page 859). C shares just waste your money. Some firms have quit selling C shares, too.

C shares—You pay no front-end or back-end load, but the annual 12b-1 is high and it never declines. For longer-term holders, this is the most expensive way to pay. C shares are cheaper than A shares only if you sell within five years or so, and why would you buy a load fund if you intended to hold for only five years? If you want to trade in and out of mutual funds, go with a no-load or an exchange-traded fund (page 859). C shares just waste your money. Some firms have quit selling C shares, too.

There’s a Beautifully Simple Way of Comparing All These Fees and Share Classes with Just a Few Mouse Clicks. Go to the excellent Fund Analyzer at www.finra.org/fundanalyzer. Enter the names of the funds you’re interested in and choose three to compare. The calculator shows how much each fund will cost you year by year for 20 years, assuming a 5 percent return, and how much you’d net each year if you redeemed your shares. You can compare a load fund’s A, B, and C shares in the blink of an eye, to see the best way to buy. Or compare two competing target-date 2025 funds or two competing index funds. All the funds’ fees are broken out. You’ll see immediately how many more dollars a low-cost fund will put in your pocket. You can store the data on up to 50 funds for future reference.

The analyzer also shows you each load fund’s break points and lists its other fees and terms, such as whether you can sell shares and then repurchase them at no sales charge within a limited period of time. You can use this calculator to compare exchange-traded funds too, or compare an exchange-traded fund with a similar, traditional mutual fund. It’s a terrific tool.

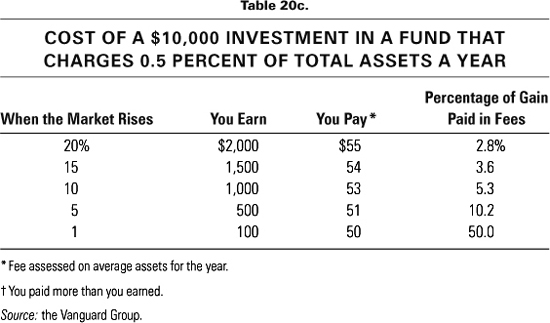

Here is the average annual percentage of assets you pay for various types of open-end funds, both no-loads (no sales charges) and similar load funds. These expense ratios include all money management and overhead costs but no front- and back-end sales charges, so the load funds cost even more than it appears. Smart investors, in funds of any type, stay away from those that charge higher than average fees.

This tells you how fast the fund manager buys and sells. An 80 percent turn-over rate means that 80 percent of the portfolio’s average value changes in a single year. Generally speaking, 20 percent is a low turnover rate for stock portfolios; 80 percent, about average; and 120 percent, high. Rapidly traded funds have high transaction costs. To compensate, they need superior returns. Among funds that make high-risk investments, a high rate of turnover might help if the manager can choose the right stocks. Among lower-risk funds, it generally hurts. As a general rule, high trading costs reduce returns.

The financial tables show the fund’s results per share, in dollars and cents, for up to the past 10 years. Some parts of the table won’t interest you, but there are some nuggets here—especially the bottom line. Here’s what to look for:

Net Investment Income (Loss)—shows what the fund is earning in interest and dividends, after expenses. Income funds will show larger dividends; aggressive growth funds, smaller ones. The fund has to pay out at least 98 percent of what it earns.

Dividends from Net Investment Income—your dividends per share. Income investors can look back to see how reliably the fund has paid. You can take this distribution in cash or reinvest it in more fund shares.

Net Realized and Unrealized Gains (Losses)—shows how the securities are performing. Aggressive growth funds may show larger capital gains; income funds will show smaller ones. Realized gains are distributed to investors. Unrealized gains remain in the fund.

Distributions from Realized Capital Gains—your share of the taxable capital gains. The fund distributes at least 98 percent of its net capital gains (after deducting losses). You can take this distribution in cash or reinvest it in more fund shares.

Net Asset Value, Start of the Year and Net Asset Value, End of the Year—shows the value of each share at the start and end of each year, after distributing income and capital gains. A common investor mistake is to think that the change in the net asset value equals the total return. It looks low, so you think that you’re not doing well. But to figure your actual total return, you have to include all the distributions too—the dividends and capital gains. If they’re reinvested automatically in new fund shares, multiply the number of shares you now own by the fund’s net asset value. That shows you what your investment is currently worth. Do this at the end of each year to see how your investment has progressed.

Ratio of Expenses to Average Daily Net Assets—gives you a figure for operating expenses. This ratio should fall when net asset values rise. If it stays level or rises too, the fund isn’t managing its expenses well.

Total Return—the payoff line. This tells you what percentage return the fund earned (or lost) in every fiscal year. Look back at the record. Does the fund bounce around a lot—a great year followed by a lousy year—or is it reasonably consistent? How high has it gone in a good year and how low in a bad year, and is the low okay with you? If the fund changed managers, can you spot a difference in the annual returns? Even if it didn’t change managers, do the recent returns suggest that the investment method might have changed? One warning: you can’t use these returns to compare the performance of two different funds. Funds have different fiscal years, so their returns may be shown over different time periods.

For the fund’s return compared with a standard market index, see the annual shareholders’ report. Sometimes it’s in the prospectus, but usually not. You’ll also find it at www.morningstar.com.

Most funds are led by an individual money manager. The prospectus provides the manager’s name and how long he or she has been there. For a manager with a short tenure, you also get a sketch of his or her business career for the past five years.

If the manager leaves, you must be informed. The change can be shown in the prospectus (check this when you get your new prospectus every year), or you might get a notice in your midyear report.

If your fund is run by a team of managers, it doesn’t have to note when one of them departs. But except for index funds and money market funds (which don’t have to disclose a manager’s name), there’s almost always a single shot caller. Check for managers’ tenure, to try to judge whether the team has changed.

You know from the annual report how the fund performed, but you don’t know how you performed. Your total return will be different from the fund’s if you added money during the year (for example, by reinvesting dividends) or took money out. Maybe you earned more than the fund because you invested or withdrew at a lucky time. Maybe you earned less. Financial planners who manage your money will report your personal, annualized return, but the funds ought to tell you too. It’s not a big deal to develop the software and give you an individual report. How can you plan for the future if you’re only guessing at what rate your money is building up?

With the prospectus comes sales literature. It shows you “the mountain”—the amount by which your investment would have grown had you been in the fund for many years. But each fund’s mountain shows a different time period, so you can’t compare one with another. Nor does the mountain show each year’s percentage gain or help you spot the years when the fund didn’t do as well as the general market average. In short, the mountain is there to impress, not inform. Go to www.morningstar.com or look at the annual report for performance data compared with a standard index.

The propaganda will also explain the fund’s investment objectives and investor services. It’s a good place to start, provided that you go on from there.

Read every communication from your fund’s manager. This normally isn’t boilerplate, it’s serious stuff. All funds have to report semiannually; some report quarterly too.

These reports include financial statements for numbers mavens who understand them. They list what securities the fund held on the reporting date, for shareholders in a position to analyze them. The list isn’t current. Some of those securities will have been sold before the report was even posted on the Web. But you can see if your manager really diversifies or if he or she makes big bets on certain industries.

The annual report has to show you how the fund performed relative to a standard market index. Some funds skip this step in the semiannual report, which gives their managers six months to string you along. (In this case, go to Morningstar. It knows.)

A distribution is money paid out by a mutual fund to its investors. An income distribution (known as a dividend) comes from the interest and dividends earned on a fund’s securities. A capital gains distribution is the net profit realized by selling securities that rose in price (after subtracting any losses). Common-stock funds generally make distributions once a year.

Before buying a fund, check its distribution date. If you buy just before a distribution (usually in December), you’re buying yourself an extra tax. Say, for example, that a fund is selling for $10 a share. The planned distribution is $1 a share. After the distribution, the fund will sell for $9—reflecting that $1 was paid to shareholders. The fund has not lost money! Investors still have $10, but only $9 remains part of the fund’s net asset value. The other $1 is in your pocket or reinvested in additional fund shares. If it’s reinvested, the value of your fund account will go back to $10. Still, that $1 distribution is a taxable dividend. When you buy just before the distribution, you get that year’s tax without profiting from the fund’s gains.

The best time to buy is right after the annual distribution date. If you want to sell, consider waiting until after that date so you’ll collect the dividends you’ve earned. That’s especially important for investors selling at the end of the year, to nail down a tax loss. If the dividend will be paid on December 14, sell on the 15th, not before.

Stock funds often make distributions quarterly. Bond funds may declare dividends daily and pay them monthly, so timing your purchase isn’t an issue. Money market mutual funds credit interest daily.

Even on stock funds, the distribution date doesn’t matter if you own the fund in a tax-deferred retirement plan.

1. Reinvest everything in more fund shares (the right option for anyone trying to lay a nest egg).

2. Reinvest enough of the distribution to preserve your capital’s purchasing power (the right option for people who need income but will be living on their capital for many years). The rest can be withdrawn and spent.

3. Receive everything in cash (the right option for anyone deliberately eating up a nest egg—usually in late old age).

If I had my investment life to live over again, here’s what I’d do: from the very first day I got a steady paycheck, I’d put money away regularly. If I couldn’t do it through payroll deduction, I’d do it through automatic payments from my bank into a mutual fund. You can set it up yourself through your online bank account or ask the fund to set it up for you. Some funds let you start an automatic monthly investment plan with as little as $50 plus additions of only $25 a month. If you’re eligible, your investment can go into funds held in a tax-deductible retirement plan. Otherwise, put it into a regular, taxable account. If you have a retirement plan at work, use your outside mutual fund account to buy types of investments that your company plan does not include.

I sure wish I’d done it. I got smart too late.

Almost all funds offer traditional and Roth Individual Retirement Accounts, Simplified Employee Pensions, and 403(b) plans. You can roll money out of a 401(k) at work and into a mutual fund plan tax free. You can also transfer money held at an old IRA to a new one at another fund company. The company will tell you how.