Income Investing—The Right Way and the Wrong Way

Seeking future security, people drop stocks and buy bonds.

Out of the frying pan, into the fire.

Properly used, bonds are safe and solid investments. They pay regular income and protect wealth. But they’re not without risk. Investors relying only on bonds for income may find themselves eaten up by inflation and taxes. Investors seeking safety may suffer capital losses. Bonds are essential to your investment plan, but you have to know how to play them right.

… a loan. You lend money to a government or corporation and earn interest on the funds. After a certain period of time, the borrower pays the money back. When you “buy” a bond (through a discount broker or full-service stockbroker), you are accepting an IOU. Some bonds are secured by company assets, giving you a claim on those assets if the company fails. Other bonds are unsecured. One class of bonds, called zero-coupon, pays no current interest; instead your interest builds up inside the bond and is paid at maturity.

Bonds come in several types: Treasuries, issued by the U.S. government; governments, issued by various U.S. government agencies such as Ginnie Mae (page 931); corporates, issued by corporations; tax-exempt municipals, issued by cities, states, and other municipal authorities; international government or corporate bonds; and asset-backed securities, issued to help finance auto, credit card, mortgage, and other loans. The complex products that got into trouble during the 2007–2009 credit crunch—things like collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs, page 969)—are also asset-backed securities. Don’t mess with them.

… a higher-rate certificate of deposit. Bond investors shoulder some risk. Usually your principal and interest are paid on time, but they might not be if the issuer goes bad. Furthermore, the bond’s underlying value goes up and down as market conditions change. If you sell a bond before maturity, you might get less (or more) than you paid. A CD’s value, by contrast, always remains the same.

… like a bond. You can hold a bond until maturity or until it’s redeemed by the company and get all your money back. But there’s no special date when a mutual fund will return your original investment. The market value of the fund changes every day—sometimes rising, sometimes falling. How much you get when you sell your shares depends on market conditions at the time.

Many companies, including financial companies such as banks and brokerage firms, sell COBRAs, or Continuously Offered Bonds for Retail Accounts.* They may have fixed rates or variable rates. They mature in anywhere from 9 months to 30 years. They’re packaged for easy sale to retail investors like you, with $1,000 minimums. It’s easy to use them for laddered portfolios that pay a steady income stream. Some are noncallable, meaning that the company can’t redeem them early if interest rates decline.

These notes, like most corporate bonds, aren’t secured by any of the company’s assets. If the company enters bankruptcy, your claims are so low on the list that you probably won’t be repaid. If you want your money back before the notes mature, you may find them difficult to sell—especially if the company is having any sort of financial trouble. What makes these notes different from bonds is that there’s no public trading market. The brokerage firm that sold you the notes maintains a market and probably will buy them back (at some discount from face value), but you can’t count on it. One exception: if you die, your survivors can usually (not always) sell the notes back to the brokerage firm at face value. Check this point in the prospectus.

Best advice: if you like the convenience of these notes, stick with top-rated AAA, AA, or A securities, fixed interest rates, and shorter terms. If only lower-grade notes are on offer, that tells you something. Extra risk.

Why not, indeed? Certificates of deposit are the very best choice for people who want total simplicity, no fees, and guaranteed principal at all times.

But bonds have other advantages. Some are fully or partly tax free, whereas CDs are fully taxable. And they usually yield higher returns than comparable CDs.

Use high-quality bonds to:

1. Preserve your purchasing power. For this you want intermediate-term bonds (maturing in roughly five to seven years), with all the income reinvested. Your money won’t grow very much, after taxes and inflation. But you’ll hold on to the value of what you have. You could also buy Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

2. Reduce the risk of owning stocks. Bond prices tend to rise and fall at different times than stocks, and at different rates of speed. So if you own both stocks and bonds and average their performance together, you have a more stable portfolio than if you owned only one of them. Put another way, bonds secure your financial base so that you can afford to take the risk of stocks.

3. Provide income to live on. Bonds pay interest you can count on. But exactly how to invest for income isn’t as clear-cut as you might think (page 920). You might want a mutual fund withdrawal plan (page 1142) instead of straight interest income from bonds.

4. Protect you in an emergency. If you lose your job or face some other financial emergency, you’ll need your savings and investments to get you through. If you own only stocks and the stock market is down, you’ll be selling at a loss to raise the funds you need. If you own bonds as well as stocks, however, you can sell the bonds instead—probably at no loss or just a little one. You’ll be able to leave your stocks alone to recover when the market turns up again.

5. Improve the yield on money you’d otherwise keep in cash. Prudent investors hold cash for unexpected expenses or expenses they know they’ll have in the next two or three years. Treasury bills, money market funds, or bank CDs are the safest places for your “prudence fund.” But you can pick up a half point or even a full point in yield by switching to short-term (two-year) bond funds. When stocks tumble, short-term bond prices may also decline. But the drop may be small, provided that the fund is managed conservatively. If you have no emergency need for cash, you can hold your short-term bond fund until it recovers and earn more than if you had stuck with money market funds. If an emergency does overtake you at a time when bond prices are down, selling your short-term fund should result in only a modest loss.

For bonds and bond funds, I emphasize conservative—meaning yields in line with AAA to A securities. Funds with higher yields can be as risky as stocks.

Higher-risk bonds come from companies or municipalities with financial troubles (or potential troubles). Troubled companies may default. Troubled municipalities will probably pay, but their credit rating and market price will fall. Bonds with longer terms are also higher risk, even if their credit quality is high. If you’re looking for safety here are five questions to ask about any bond fund you buy:

What’s the credit quality? You’re shopping in the AAA to A range (page 918), not BBB or below. Ask the fund what its average credit quality is. No-load funds give their rating online. The lower the credit quality, the riskier the fund.

What’s it investing in? Bond funds that look sedate on the outside might actually be managed by gunslingers. Those are the funds that dropped 10 percent or more in the crash of 2008. Some of them invested heavily in lower-rated issues (BBB-minus and below) or unrated bonds. That’s something you can check in the prospectus or on the fund’s online snapshot before you buy. What’s harder to see are the exotic strategies that a manager might use—high leverage (borrowed money) and complicated derivatives that turn an apparently A-rated fund into a time bomb. These strategies are also disclosed in the prospectus but the average investor will have a hard time grasping what they mean. My advice: don’t try, just run away. The risks aren’t worth the slightly higher yields that these funds might pay.

What’s the duration? For a full explanation of duration, see page 911. Short durations shield you from too much risk; long durations expose you to larger price swings and explain the sudden losses that can occur when interest rates go up. An optimal duration is three to four years. At that point on the spectrum, you’ve increased your yield without adding too much extra risk. A speculative duration is six years or longer. No-load bond funds show their durations in the snapshots they provide on their Web sites.

What’s the volatility? This one is trickier. A bond fund may appear to have a short duration, but if interest rates drop, the duration may lengthen. The fund’s price may plunge further than you believed it could. That’s because the fund buys risky securities—the market’s toxic waste. You can tell that a fund is risky if it yields markedly more than its peers. (Funds that buy mortgage-backed securities such as Ginnie Maes also have changing durations, not because they’re especially risky but because that’s the way those investments work. You simply have to be prepared for changes in price.)

What’s the currency? Dollar-denominated bonds reflect only credit quality and interest rates. Foreign-currency bonds also reflect the changing value of the dollar in the world. They’re a bet on currency changes, not a pure interest rate decision (page 976).

Try to evaluate all five risks. Alternatively, stick with classic, well-diversified bond mutual funds from the major no-load families, which don’t take hidden risks and behave as expected in the market.

Flip the advice in the previous paragraphs. Look at funds that buy bonds of lower credit quality, longer durations, or denominated in other currencies. You take on more risk—that is, more chance of higher returns than you’d get from more conservative bonds—but also the considerable chance of getting poor returns. High-yield bonds aren’t for the “safe” part of your portfolio. They’re always better bought in mutual funds—if, indeed, you want them at all (page 936).

Whether to buy a bond or a bond fund is often a tough call. Whereas stock investors clearly belong in mutual funds, many bond investors may be better off owning bonds individually. Here are the issues. You decide.

1. You want a guarantee that you’ll get your principal back plus a fixed investment return. You’ll get it if you buy high-quality bonds and hold them to maturity. The holding period is critical. If you have to sell before maturity, you’ll take a discount on the price—and the smaller your investment, the larger the discount. Best advice: buy Treasuries, or buy corporates or municipals rated A and up. Stick to 5- to 10-year terms, no longer. You’ll get all your money back.

To test whether you’re sure you can hold bonds to maturity, ask yourself this: Could I afford to keep them if I lost my job? Even if the value of all my other investments dropped? If the answer is yes, you’re okay with individual, high-quality bonds. If the answer is no, go to mutual funds.

Mutual funds don’t offer you a maturity date, so you aren’t guaranteed a fixed return. You can’t even be sure that, on the day you sell, you’ll get all your principal back. You probably will—especially if you hold the fund for several years. Still, your true yield depends on the fund’s market value at the time.

2. You want to minimize costs. Buy newly issued bonds. You’ll get the same price that the big institutions pay, and the issuer swallows the sales commission. At maturity or when the bond is called (page 911), you can redeem it through the issuer’s paying agent at no fee.

With mutual funds, on the other hand, you pay annual fees, the amount depending on the fund you choose. If you buy from a broker, you’ll also pay sales commissions. These costs reduce your investment returns.

Warning: your costs go up if you buy older bonds out of a stockbroker’s inventory. The broker will be eager to sell them because they carry lucrative price markups—up to 5 percent and sometimes more. Discount brokers’ prices are expensive too. Mutual funds get much better prices on older bonds than you ever will. Note that if you work with a fee-only investment adviser (page 1175), he or she may buy you older bonds at wholesale prices. That works.

3. You don’t need to diversify. You can’t afford a lot of diversification when you buy individual bonds. That doesn’t matter if you invest in Treasury securities. You should also be okay with municipals and corporates rated A or better that mature within 10 years or less—assuming that you can hold them for their full term.

The minimum investment on individual bonds is generally $5,000 for corporates and municipals and $100 on Treasury notes and bonds (for the latest on Treasuries, check Treasury Direct at www.treasurydirect.gov).

In conclusion, buy individual bonds if: (1) You’ll buy only new issues; (2) you’ll buy Treasuries or other top-quality bonds, so default won’t be a worry; (3) you’ll hold the bonds until maturity.

1. They’re convenient. A professional manages your money and can buy bonds at wholesale prices. You don’t have to think about which bonds to buy and whether you’re getting a good price.

2. Your dividends can be reinvested automatically, earning the same yield that the bond fund pays. With most individual bonds, by contrast, you have to put your dividends into lower-yielding bank accounts or money market funds—that is, if your objective is to keep them safe. (The only individual bonds that let you reinvest at the same rate are zero-coupons; page 946.) Reinvestment options aren’t material, however, if you plan to live on the income from your bonds.

3. You want to be diversified. Bond funds spread your money over many different issuers. This is critical to investors attracted by the higher yields on medium- to lower-grade bonds. Some of the lower-grade bonds may default. To minimize that potential loss, you need to own a piece of many different issues.

4. You can invest in corporates and municipals with small amounts of money. The initial purchase may be $1,000 to $3,000, after which you can make small, regular contributions. Even smaller contributions are accepted in an Individual Retirement Account or 401(k). But mutual funds aren’t only for small investors. Individuals with large amounts of money buy them too.

5. You think that you probably could hold a 5- or 10-year bond to maturity, but aren’t sure. Funds are for people who want access to their money at any time, without running the risk of having to sell at a discount.

6. You want to speculate on a decline in interest rates. When interest rates fall, bond values rise, and you could sell your fund shares for a capital gain. The value of individual bonds would increase too, but you wouldn’t get as good a price if you tried to sell. Speculators should buy only no-loads. Gains melt away when you have to pay front-end or back-end sales commissions.

In conclusion, buy bond funds if: (1) You want to be well diversified— especially important when buying lower-quality bonds; (2) you have only a modest amount of money and want to earn more than Treasuries pay; (3) you have a lot of money and want it professionally managed at a low fee; (4) you want to make regular, small contributions; (5) you aren’t sure of your holding period and want to be able to sell at current market value at any time; (6) you’re speculating on a decline in interest rates (good luck!); (7) you want the advantage of automatic dividend reinvestment.

To Me, the Answer to the Question “Bonds or Funds?” Turns on These Two Points: (1) Do you demand, to a high degree of certainty, that by a specific date you will get all your capital back, in addition to all the interest you’ve earned—and will you hold until that date? If so, buy high-quality bonds, not funds. (2) Do you need a lot of flexibility, to sell anytime you might need the cash? If so, buy bond mutual funds.

If You Decide on Bond Mutual Funds: Bonds of similar types and credit quality behave pretty much alike. They pay similar rates of interest; their prices in the marketplace rise and fall by similar amounts. Bond-fund managers can’t outperform their peers by making “smarter” choices within their bond universe. They outperform only by making riskier choices, which means there’s also a chance that they’ll underperform. Actively managed funds, where the manager chooses which bonds to buy, have a hard time competing with index funds, which passively follow a leading bond index—especially after costs.

Most likely, you buy bond funds not to gamble on higher yields but to reduce your risk. You can get both—better yields and lower risk—by choosing high-quality funds with rock-bottom expenses. Two no-load mutual fund companies offer especially low expenses on bond funds of all types: the Vanguard Group (www.vanguard.com) and Fidelity Investments (www.fidelity.com). I suggest that you limit your bond fund shopping to these two firms.

What About Closed-End Bond Funds? These are baskets of bonds, either corporate or municipal, assembled by an investment house and sold to the public. They trade like stocks, on a stock exchange, which means that you buy them through brokerage firms. The portfolio is professionally managed, so your bond investments change with time. You receive monthly or quarterly payouts of the fund’s interest earnings; at the end of the year, you receive any realized capital gains. Closed-end funds are best for investors who buy and sell funds, seeking capital gains, not for investors seeking steady income. For more on closed-ends and how they work, see page 784.

What About Exchange-Traded Funds? ETFs are a form of mutual fund that’s bought and sold like stocks, on a stock exchange. For an explanation of how they work, see page 859. They’re not the best choice for people accumulating assets because you’re always paying brokerage commissions. But they have charms for people seeking a combination of income and liquidity. You might use them instead of a bond ladder (page 921). They’re also good for people speculating on lower interest rates.

Is There a Case for Buying Bonds in a Unit Trust? I’m skeptical, although unit trusts are widely sold for this purpose. Read more about them starting on page 958.

There’s no case for excluding fixed-income investments from your portfolio. Treasuries, in particular, are a hedge against the risk of seriously unpleasant times.

You never know which type of financial asset will perform the best over the next five years—stocks, bonds, or cash. A particularly good time to buy bonds has been when stock dividends are low. As I write this, in 2009, bonds have outperformed stocks since 2000, a year when dividends were a puny 1.2 percent. Since then, they’ve doubled to 2.4 percent. Traditionally, a high dividend would be 5 percent.

Can bonds outperform again? Let me read you every investor’s Miranda warning: past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. But you never know. The easiest way to capture potential market gains in bonds is by owning mutual funds. As a diversified investor, you should own them anyway, because bonds are a safety net. Besides, have I said it before? You never know.

1. Do not—repeat, not—invest most of your retirement plan money in bonds when you’re middle-aged. This is a waste of your precious youth. Adjusted for inflation and taxes, bonds give you only modest growth (and sometimes negative growth). Middle-aged people need significant holdings of stocks. This is true even though stocks go through patches of poor returns. You never know when they’ll turn up again.

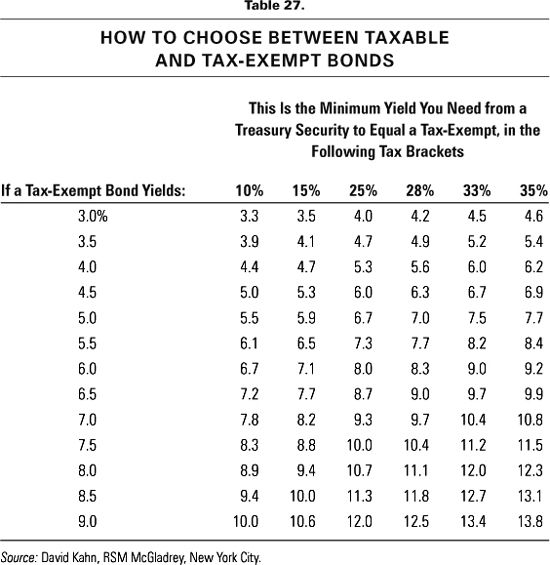

2. You should not—repeat, not—buy tax-free municipal bonds without checking to see if they’ll give you a competitive yield (page 941). They’re a best buy when they’re yielding about the same as taxable bonds; that’s rare, but we saw it in 2007–2008. Under normal conditions, you’ll profit if you’re in the 25 percent tax bracket and up. In lower tax brackets, buy Treasuries or corporates.

3. You should not—repeat, not—put tax-free bonds into your tax-deferred Individual Retirement Account. You owe taxes on withdrawals from traditional IRAs. If you use IRA money to buy munis, you’ll be converting them into a taxable investment. Don’t put them in Roth IRAs either. Roths accumulate tax free, so they’re the place for corporate bonds and bond funds that would otherwise be taxable.

4. You should not—repeat not—put most or all of your money into long-term bonds and CDs when you retire, in order to live on the income. You may live 30 years or more, and over that time the purchasing power of your money—both interest and principal—will collapse. (For more on investing at retirement, see page 1142.) Around 40 percent of your money should be in stocks.

5. You should not—repeat not—pay any attention to this last piece of advice if you’re scared of stocks, don’t know anything about them, and can live on your pension, Social Security, and interest income. In this instance, you might not even want a bond mutual fund because it will occasionally show a loss.

People unwilling to tolerate occasional losses are candidates for tax-free bonds, Treasuries, and bank CDs. As the value of the fixed portion of your income shrinks, you can compensate by dipping into capital (the longer you live, the fewer years you have left, and the less capital you will need for future expenses).

Financial advisers can yammer away about optimal returns until they’re blue in the face. What you deserve from your money more than anything else is the sense that you’re secure.

For an explanation of how best to use bonds for income, jump to page 920. But you’ll understand the strategy better if you first learn how bonds work.

Repeat after me:

Falling interest rates are good. When interest rates fall, bond prices rise. If I hold a bond mutual fund, its share price will go up.

Rising interest rates are bad. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. If I hold a bond mutual fund, its share price will decline.

These basic principles of bond investing stand behind every paragraph of this chapter, so remember them.

If you buy individual bonds and hold to maturity, changes in market prices don’t matter. When the bond matures, you will get your money back.

If you buy bond mutual funds and hold for long enough, you may also make money even if interest rates go up. That’s because the fund keeps buying new bonds at those higher rates, and the extra interest eventually overcomes your loss of principal. In general, rising rates recoup your losses after about two years if you’re holding a short-term fund; five years, for an intermediate-term fund; and eight years, for a long-term fund.

Bonds have several values:

The Principal. When you put up $1,000 for a new bond, you will get $1,000 back on the day the bond matures. That’s your principal. The bond’s face value is known as par.

The Price. When you read that a bond costs 100, that means $1,000. It’s “100 percent of the par value.” When you read that a bond costs 95.25, that means $952.50, or 95.2 percent of the par value. To get the dollar price, you add a zero to the quote.

The Interest Payment. Most bonds pay interest semiannually on your money. The interest rate is called the coupon. A $1,000 bond paying $50 a year ($25 semiannually) has a coupon rate of 5 percent.

The Market Price. If you want to sell your bond before maturity, the price will depend on market conditions. Remember your mantra. If interest rates have risen since your bond was issued, your bond is worth less than it was when you bought it. If interest rates have fallen, your bond is worth more. This is the most critical fact about bond investing and the least understood. The interest payments that you get from your bond remain the same. But the market price continually adjusts, so your bond always yields the return that investors currently demand. This makes no difference if you plan to hold your bond until maturity. But it makes a big difference if you want to sell ahead of time or if you own a bond mutual fund.

The table on page 909 shows how the bond market works. The left-hand column shows how interest rates might change. The right-hand column shows the effect of these changes on the price of a particular bond.

When you buy individual bonds, always buy new issues! These are bonds newly offered to the public by government bodies or corporations. The issuer pays the broker’s commission. You get a prospectus explaining what the money is being raised for and what (if anything!) is backing your interest and principal payments. You want a well-backed bond.

New-issue bonds come at an honest market price. No one can monkey around with the stated yield. On the whole, new-issue transactions are simple, sweet, and clean.

This is really all you need to know about buying individual bonds.

What gets you into trouble is buying older bonds. Dealers have huge inventories of these bonds, so one can be found that exactly serves your purpose. Older bonds are part of the so-called secondary market.

| HOW BOND PRICES CHANGE | ||

What Happens in the Market |

|

What Happens to Your Bond |

You buy a new 30-year bond. You pay its par value and earn a 6 percent coupon. |

|

Your $1,000 bond, at 6 percent interest, pays you $60 a year. |

Immediately, market conditions change. Newly issued bonds now have to pay 6.5 percent in order to attract investors. |

|

The market value of your $1,000 bond drops to $934.* Its fxed $60 interest payment now produces a 6.4 percent current yield. You have an unrealized loss on your investment of $66. The bond is said to be priced at a discount. |

Market conditions change again. Newly issued bonds now have to pay only 5.5 percent in order to attract investors. |

|

The market value of your $1,000 bond rises to $1,073.* Its fxed $60 interest payment now produces a 5.6 percent current yield. You have earned $73 on your original investment. The bond is said to be priced at a premium. |

Thirty (zzzz) years later . . . |

|

You have collected a total of $1,800 in interest payments ($60 a year). The market value of your bond might have dropped to $900 in some years and risen to $1,100 in others. When the value was high, you could have sold for a proft. If you didn’t, you’ll redeem it for $1,000—earning the 6 percent annual return you bargained for. |

Source: The Vanguard Group, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania |

||

What’s wrong with buying older bonds? In a word, price. All things being equal, an older bond costs more than a new one because of the dealer’s markup—the additional sum that is added to the wholesale price. You won’t find the markup on your confirmation statement. Any sales commission or transaction fee disclosed will represent only a portion of the real price you paid.

The biggest markups (and sales commissions) are usually on longer-term and zero-coupon bonds (page 945). There are also big markups on all the firm’s garbage: bonds of poor credit quality or oddball bonds with virtually no resale market. The brokerage firm’s rules might say that brokers aren’t supposed to sell that stuff to retail investors, but they sometimes do.

A few years ago, it wasn’t uncommon for brokers to charge excessive (hidden) markups even on garden-variety bonds. That pretty much ended when the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority introduced TRACE (Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine), which tracks all corporate bond transactions. Go to www.finra.org/marketdata and enter the name of the company whose bonds you’re interested in. You’ll get a list, along with the bonds’ coupon interest rates, maturities, ratings, market prices, and current yields. Check any particular bond that your broker recommends. According to industry guidelines, firms are not supposed to charge a markup of more than 5 percent. Competition should drop the cost lower than that—say, $20 on a long-term bond and $10 on an intermediate bond. Still, there are rogue brokers out there. In 2007 FINRA fined Morgan Stanley $6.1 million for letting its brokers mark up bonds by as much as 16 percent.

Contrast this with what you pay for a Vanguard bond mutual fund—about 0.2 percent a year. From a cost point of view, funds are a much better buy than bonds on the secondary market.

If you’re buying older municipal bonds, you can check their wholesale prices too. They’re tracked by the Real-Time Transaction Reporting System, run by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), which regulates the muni market. There are two sites:

(1) Investinginbonds.com (www.investinginbonds.com), run by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. Click on “Municipal Market At-A-Glance,” and enter the state whose bonds you’re interested in. You can sort by various criteria, including maturity, price, and yield. (SIFMA also offers TRACE data for corporate bonds, but the TRACE site is more complete.)

(2) The MSRB’s Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA, at www.emma.msrb.com). Click on “Advanced Search” to sort by various criteria. You can even search for bonds of a particular type. For example, if you live in Kansas and want a sewer bond, you can enter the state and the word sewer to find out what’s available.

Both sites provide the Official Statement issued with most bonds, explaining the terms of the deal and what the proceeds are being used for. You’ll also find consumer information about investing in munis.

One more source of information: the Markets Data Center at The Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/public/us). There you’ll find prices for the most widely traded bonds.

Once you stray off the straight-and-narrow path of new-issue bonds, you land in a briar patch. A few of the terms listed here apply to every bond. But most of them describe the pricing of older bonds that are selling for more, or less, than their face value. To explain these terms, I’ll use the examples I gave in the table on page 909, starting with a $1,000, 30-year bond paying 6 percent interest.

Coupon. The fixed-interest payment made on each bond. A $1,000 bond paying 6 percent a year has a $60 coupon. Put another way, its coupon rate is 6 percent. It is typically paid semiannually—$30 every 6 months.

Current Yield. The coupon interest payment divided by the bond’s price. A new-issue $1,000 bond paying $60 a year has a current yield of 6 percent. If the price of the bond drops to $934, the current yield—still based on a $60 interest payment—would rise to 6.4 percent. (Remember your bondspeak: at $934, the price would be quoted at 93.4.)

Premium. The amount by which the bond’s market value exceeds its par value. A $1,000 bond selling at $1,073 carries a $73 premium. Bond prices can go to premiums when interest rates fall.

Discount. The amount by which the bond’s market value has fallen below the par value. A $1,000 bond selling at $934 is at a $66 discount. Bonds go to discounts when interest rates rise. If you buy at a discount and eventually realize a profit, that profit is taxed as ordinary income, not a capital gain.

Call. When the issuer decides to redeem a bond before its maturity date. For example, a bond maturing in January 2020 might be called in September 2010, and you’d have no choice but to surrender it. The earliest possible call date is usually specified in the bond contract. Some bonds are callable at any time. The call price is usually the par value plus a sweetener.

Term. Generally speaking, short-term bonds run for under 3 years. Intermediate-term bonds run up to 10 years. Long-term bonds go longer than that.

Duration. Duration doesn’t affect you if you buy individual bonds and hold to maturity. It’s a sophisticated measure for two groups of people: (1) investors who speculate in bonds—buying in hope of a price increase so they can sell at a profit; and (2) bond-fund investors wondering which of two similar funds carries the higher risk.

By risk, I mean how far the fund’s price might drop when interest rates rise and bond prices decline. A general measure is the fund’s maturity. Long-term bonds swing more in price than short-term bonds do (page 909). But what about two bond funds of the same average maturity? One might be riskier than the other because of the kinds of investments it makes.

That’s where duration comes in. It estimates how violently a bond or bond fund will react to a change in interest rates. The shorter the duration, the less price change you can expect.

When you’re looking at two bond funds with similar credit ratings, maturities, and yields, ask about duration (you’ll find the duration on the Web sites of no-load funds; for load funds, ask your broker). If one fund has a noticeably higher duration, it carries more market risk. When you take higher risks, you should be rewarded with higher yields. Some bond funds have changing durations (see “What’s the volatility?” page 901). They shouldn’t be offered to individual investors in the first place (except for funds that invest in mortgages).

Yield to Maturity. What your bond would earn if you held it to maturity and reinvested each interest payment at the same yield paid by the bond itself. For example, if the broker says that your yield to maturity is 5.4 percent, that assumes that every single interest payment is reinvested at 5.4 percent. If you spend your interest income or reinvest it at a lower rate, as usually happens, you will earn slightly less. That’s not a big deal if you buy the bond at par ($1,000). But if you buy an older bond, there may be a marked difference between the current yield and the yield to maturity. Because of this difference, you might be flimflammed into buying a bond that yields less than you think.

For example, say that new 10-year bonds are selling at 5.4 percent yields. Your broker calls you up one day and says, “Hey, I have this nice little number at 6 percent.” “Great,” you say. “Buy.” You think that the bond is beating the market. But your broker doesn’t mention that the bond costs $1,046, a $46 premium. At maturity, you will redeem the bond for $1,000, taking a $46 capital loss. Your yield to maturity, counting that loss, would be 5.4 percent. So you’re getting less than your broker claimed. If the bond is called before maturity (as bonds selling at premiums often are), you might get less than 5.4 percent. You’d also get less if the broker charged you more than $1,046 for the bond.

The reverse is true when you buy a bond selling for less than its face value. Say that you pay $946 for a $1,000 bond. At maturity, you’ll have a $54 gain. Counting that gain, the bond’s yield to maturity will be higher than its current yield. Why would you deliberately buy a bond reporting a lower current yield? Because the issuer isn’t likely to call it early. You accept less current income in hope of hanging on to the bond’s high yield to maturity, including its built-in gain. (I say “in hope” because this strategy doesn’t always work. If interest rates fall far enough, these bonds too may rise to premiums and be subject to a call.)

So … always check an older bond’s price and yield on TRACE (page 910), to see if your broker is charging a fair price. Better yet, consider buying only newly issued bonds, not older ones.

Yield to First Call. This is what a bond will yield if the issuer calls it (repays it) at the earliest date the contract allows. It’s also the yield that you will most likely get if you buy a bond that’s selling at a premium (that is, over $1,000). In the previous section, I showed what the yield to maturity might be for a premium bond—that is, a bond selling for more than its $1,000 face value. But that was just an academic exercise. In real life, the issuer won’t let you keep those bonds until maturity. They pay high current rates of interest, and the issuer will want to replace them with bonds paying lower rates. So the information you really need is the yield to the first date that these bonds can be called. That’s your likeliest yield and holding period.

Continuing the example used in the previous section: If you paid $1,046 for the bonds and they were called the following year, your actual yield would be only 1.4 percent because of that $46 capital loss. That’s something your broker probably forgot to mention. Anytime a broker offers you a bond with a high current yield, ask: (1) Is the bond selling above par (above $1,000), and if so, what is its yield to first call, and (2) is it a junk bond (page 936)? Most Treasuries cannot be called.

Yield to Worst. A bond may have several call dates, in which case you want to know the lowest possible yield that the bond can pay. This is called yield to worst. Always ask for it.

Tax Equivalent Yield. This applies to tax-free municipal bonds. It tells you what rate of return you’d have to earn on a taxable bond to equal what you’re getting from the muni, in your tax bracket.

Total Return. Ultimately, this is the only return that matters. It’s all the money you earn on the bond or bond fund, and it comes in two parts: (1) the annual interest and (2) the gain or loss in market value, if any.

For example, take a $1,000 bond with a 6 percent coupon, and assume that bond prices go up. If you sell that bond for $1,050, your total return that year (before brokerage commissions) is $110, or 11 percent—$60 from interest and $50 from the gain in the market price.

Or suppose that you pay $1,050 for a $1,000 bond with a $60 coupon, for a current yield of 5.7 percent. If you sell that bond one year later for only $1,000, you’ll have taken a $50 loss. Your total return is $10, or 1.0 percent—$60 from the bond interest minus the $50 loss.

Out of all these yields, brokers have created so many sophisticated fiddles that I couldn’t begin to understand them all. Nor would I want to. Just give me a nice new-issue bond and leave me alone. If you do buy an older bond from a broker, the only way to know what you’re getting is to ask for the current yield, the yield to maturity, the yield to first call, and the yield to worst. If you buy and hold, you get something slightly less than the yield to maturity (because you probably couldn’t reinvest your interest payments at the same rate you were getting from the bond). If you sell before maturity or your bond is called, your return will depend on the commission you pay, the call price, and market conditions at the time of sale.

Bond mutual fund managers can fiddle too, to make you think that you’re earning more than is actually the case. Because of their sorry abuse of the public in the past, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) wrote a rule dictating how yields must be disclosed. All bond funds have to do that calculation in the same way, so that you can compare them.

The SEC yield is computed from the bond portfolio’s average yield to maturity over the past 30 days, minus expenses and any sales loads. The yield is then annualized. This rule covers yields shown in advertising material, online disclosures, and automated quote services on the phone, but not what you’re told in person by a stockbroker or financial planner. So ask the broker or fund salesperson specifically for the SEC yield. Any other yield may be misleading.

Beware the distributed yield. This yield calculation counts only the interest currently paid on the portfolio, not any built-in capital losses that come from buying bonds at a premium (page 911). Distributed yields look high when the actual yield you’ll receive, after adjusting for losses, is much lower.

Here’s what else the rules say you should receive: the yield to average maturity, which is the average maturity of all the bonds in the fund’s portfolio; the yield to average call, if there’s a good chance that bonds will be called before maturity; and the fund’s total return for the latest 1-, 5-, and 10-year* periods. Funds with shorter life spans have to disclose their performance from the day they began. Total return is their interest income plus or minus any gains or losses in the value of their shares.

You cannot compute your actual yield from your dividend check. The check might not contain every penny of this term’s interest income (some of it might be in your next check). It might also include income from writing options or capital gains distributions from bonds that were sold at a profit. You have to rely on the fund to tell you what it’s yielding.

Bonds aren’t as risky as stocks. But they’re riskier than many investors realize—especially the longer-term bonds. Bond risk comes in several forms.

The market value of your bonds will rise and fall as interest rates go down and up. If you sell, you might get more than you originally paid or you might get less, just as would happen if you sold a stock. This matters only if (1) you sell your bonds before maturity or (2) you own a bond mutual fund. Anytime that you sell a mutual fund, the price is set by market rates.

Short-term bonds are safest (if they’re conservatively invested) because they fluctuate the least in price. They also pay the lowest rates. Intermediate-term bonds come next. Long-term bonds fluctuate the most.

To minimize market risk, buy a “ladder” of short- to intermediate-term bonds, as explained on page 921.

Two apparently similar bond funds can behave differently when interest rates change. A rise in rates may hurt one fund’s price just a little bit while hurting another fund a lot. The difference may depend on the fund’s duration (page 911). It might also depend on how each fund uses derivatives—complex securities where the price of one asset depends on the price change in another asset. Some derivatives increase a fund’s market risk; other derivatives lower it. A fund yielding more than its peer group may be using derivatives in a speculative way.

The longer it takes for your bond to reach maturity, the greater the chance that you’ll have to sell ahead of time. You risk losing money when you sell early because market prices might be down.

To minimize holding-period risk, don’t buy 20- and 30-year bonds. The odds of your holding that long are small. The average income investor should buy short- to intermediate-term bonds, defined as lasting no more than 10 years.

As consumer prices rise, both your principal and interest lose purchasing power. Take that $1,000 bond with a coupon of 6 percent a year. After just five years of 3 percent inflation, your $1,000 principal will have a purchasing power of only $862, while your $60 interest check will buy only $52 worth of goods. Your standard of living has dropped by 14 percent. And what will happen over the next five years and the five years after that, if inflation persists?

To minimize inflation risk, buy Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS, page 929). Their yield rises with the inflation rate.

To minimize inflation risk with corporate bonds, don’t spend all the interest if you can avoid it. Instead, reinvest enough to counter the inflation rate. For example, suppose that you own a $1,000 bond and inflation is running at 3 percent. In order to maintain its purchasing power, your $1,000 principal needs to rise in value by $30. If you’re earning $60 in interest, you should reinvest $30 (to bring your principal up to $1,030), pay the taxes due, and live on what’s left. In a bond mutual fund, reinvestment is easy. If you own individual bonds, put that $30 into a bank or money market fund. Reinvest the whole $60 if you don’t need the income to live on.

If interest rates fall, corporations and municipalities will call in their older, high-interest bonds and issue new ones at lower rates. Typically, you get 5 to 10 years’ call protection from both corporations and municipalities. The call may come at par ($1,000) or par plus a little bit extra. But that’s not much consolation. You will have been earning a high rate of interest. After the call, you’ll have to reinvest at a lower rate.

Most bonds are called through a refunding. The company issues lower-coupon bonds and uses the proceeds to retire its higher-coupon debt. You may also be parted from some of your bonds, usually long-term municipals, by a sinking fund—a lottery system for retiring a certain number of bonds each year (in which case, no sweetener is paid). A special or extraordinary redemption can occur in specified circumstances, such as changes in the economics of a project that make it unworkable.

Calls used to be one of the normal hazards of bond investing that you could hedge against successfully. Now it’s guerrilla war out there. Bond issuers tuck weasel words into the finest of print to deceive you and your broker about how early a call could come. One reason not to be a bondholder (or to buy a mutual fund and let the fund manager worry about it) is that so many corporations and municipalities are playing fast and loose with your call protection.

What do you lose when your bonds are called? If you bought at par, your principal is returned intact (sometimes with a little sweetener). But you lose the capital gain you earned when the bond’s value rose. If you paid more than the call price, you suffer an early capital loss. When a convertible bond is called, you’ll lose the higher price it might have been selling for in the open market. Calls also deprive you of high bond income that would have kept you sitting pretty for many years.

To eliminate call risk, buy newly issued U.S. Treasury notes and bonds. They are almost always callproof (or not callable until 25 years have passed, which, by me, is the same thing). Plenty of intermediate-term corporate and municipal bonds are also noncallable.

If you buy an existing bond, it’s smart to choose one with low interest payments, selling at a discount from par value. Your yield to maturity will equal that of higher-coupon bonds, but your investment isn’t as likely to be called. Or buy zeros that are callable only at par. If zeros are callable at their accreted value—meaning their original price plus all the interest earned to date—they’re no better than garden-variety bonds.

The issuer might not pay the bond’s principal and interest on time. For example, the company might go bankrupt, or its loans might have to be restructured. U.S. government bonds have no default risk. Municipals, even those of middling quality, rarely stumble. High-quality corporates are usually solid too. Low-rated bonds, especially corporates and those of developing countries, are the ones most likely to descend into default.

To minimize default risk, buy only higher-quality stuff. You will sacrifice some yield. A 10-year AAA bond might yield 0.5 percentage points less than a BBB-rated bond, depending on the market at the time. That’s a pretty small price to pay compared with the risk of losing money. To avoid default risk in the muni market, you can buy insured bonds, giving up maybe 0.15 to 0.3 percent of the yield. But what’s the point? Munis hardly ever default. In the credit crisis of 2007–2009, muni bonds turned out to be stronger than the insurers that supposedly guaranteed them. At this writing, there’s only one AAA-rated insurer left. (For more on muni bond insurance, see page 942.)

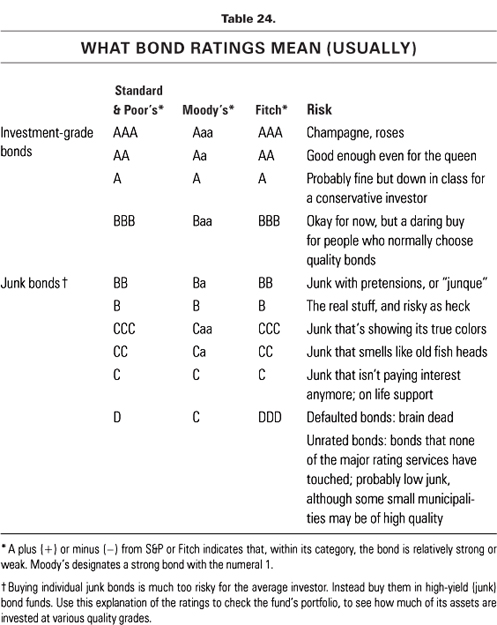

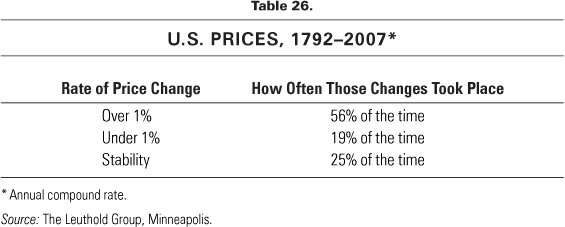

The three most common bond-rating systems, from Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch, are shown below. These systems aren’t perfect. In 2007 the firms were caught giving high ratings to what turned out to be poor-quality securities. Those were complex securities, however. With occasional exceptions, ratings on plain-vanilla securities do a reasonable job of identifying risk. You can get free ratings on public companies by registering at these sites: Standard & Poor’s (www.standardandpoors.com), Moodys.com (www.moodys.com), and Fitch Ratings (www.fitchratings.com).

If a company starts racking up losses or a municipality reveals huge unfunded pension obligations, the credit rating on its bonds will fall. As long as you hold those bonds, your interest payments stay the same (provided that the issuer doesn’t default). But if you have to sell before maturity, you’ll take a beating on the price. When a company’s or municipality’s finances improve, its credit rating rises, and so does the price of its bonds.

To minimize credit risk, check your bond’s current safety rating and whether that rating is likely to change. Moody’s publishes a “Watchlist.” At S&P and Fitch, you look up the company to see if it’s on credit watch.

There are several ways of making you think you’re earning more than is actually the case. Two examples:

1. A broker or planner may tell you that your fund’s current yield (from interest and other income) is 7 percent. But that’s only part of the story. If interest rates rose last year, your fund may have dropped in value—say, by 4 percent. So its total return—7 percent in income minus 4 percent in market losses—was actually only 3 percent. Quite a difference.

2. A unit trust might buy a three-year, A-rated $1,000 bond with an 8 percent coupon interest rate that has only one year left to run. It might be selling at a current yield of 7.8 percent, compared with only 5.5 percent on newly issued one-year bonds. The trust buys that bond in order to jack up its current yield. But it has to pay a fat $1,024 for it. When the bond is redeemed, the trust will take a $24 loss. As a result, the bond’s actual yield to maturity is only 5.5 percent. Thus are customers duped. Salespeople are supposed to give you the current yield plus the yield to maturity, which would show what you’ll really earn. Good ones do. Be sure to ask for it.

To minimize deception risk: Check bond prices on EMMA or TRACE (page 910). Check the bond fund’s prospectus for the SEC yields and the annual total returns (page 772). You can use these yields to compare one fund with another.* Use discount brokerage sites, where yields are disclosed. Buy through fee-only investment advisers. Avoid unit trusts (page 958).

You are an income investor if you expect to live on the monthly checks that your capital produces. Instead of reinvesting your dividends and interest, you take the money and spend it. For bond buyers, there’s a right way and a wrong way to go about this.

The wrong way, in my view, is to buy a lot of long-term bonds. This conclusion may surprise you because “long bonds” usually pay the highest interest rates. The year you buy them, you’ll earn some real spending money, even after inflation and taxes.

So you love Year One. Year Two, however, isn’t quite so terrific. Both your capital and your income lose purchasing power. By Year Three you are barely breaking even after taxes and inflation. By Year Four, you are probably in the hole. Each subsequent year, your bond income buys you less and less. How much less depends on the inflation rate.

If inflation holds steady or declines, you’ll get poorer slowly, losing a modest amount of purchasing power every year. For extra money, you may have to sell some bonds before maturity. If interest rates have fallen, the sale might yield a modest profit, but you’ll take a loss if interest rates are up. Small amounts of municipal bonds may be virtually unsalable. Your money may still stretch over your lifetime, but you can’t be sure. If your savings are small, the diminished real value of your bonds may force you to reduce your standard of living in later years.

If inflation holds steady or declines, you’ll get poorer slowly, losing a modest amount of purchasing power every year. For extra money, you may have to sell some bonds before maturity. If interest rates have fallen, the sale might yield a modest profit, but you’ll take a loss if interest rates are up. Small amounts of municipal bonds may be virtually unsalable. Your money may still stretch over your lifetime, but you can’t be sure. If your savings are small, the diminished real value of your bonds may force you to reduce your standard of living in later years.

If the rate of inflation rises, the purchasing power of both your capital and your income will take a devastating hit. You will have to use up your money at a much faster rate than you had planned or cut back sharply on expenses.

If the rate of inflation rises, the purchasing power of both your capital and your income will take a devastating hit. You will have to use up your money at a much faster rate than you had planned or cut back sharply on expenses.

If deflation occurs, and soon, you’ll be glad that you’re collecting income from long-term bonds. In that case, your purchasing power would rise (provided that you owned noncallable Treasury bonds; corporates or municipals would be called by their issuers, robbing you of your high-interest income). But deflation is a way-outside bet. Americans lived through bouts of deflation in the 1870s, parts of the 1880s and 1890s, and the 1930s, but not since.

If deflation occurs, and soon, you’ll be glad that you’re collecting income from long-term bonds. In that case, your purchasing power would rise (provided that you owned noncallable Treasury bonds; corporates or municipals would be called by their issuers, robbing you of your high-interest income). But deflation is a way-outside bet. Americans lived through bouts of deflation in the 1870s, parts of the 1880s and 1890s, and the 1930s, but not since.

Why take any of these risks when you can pursue a sensible income strategy with intermediate-term bonds instead? The extra yield you get from long bonds may be in the 0.5 percent range. That’s a pretty skinny bonus for putting your money at such hazard.

Buy a mixture of intermediate- and shorter-term bonds and ladder them. Here’s why:

They pay a reasonable income. It’s less than you’d get from a portfolio of long-term bonds, but usually just a tiny bit less.

They pay a reasonable income. It’s less than you’d get from a portfolio of long-term bonds, but usually just a tiny bit less.

They give you inflation protection. If interest rates rise, your maturing short-term bonds can be reinvested at a higher interest rate. That will preserve some of your purchasing power. Unlike the owners of long-term bonds, you’re not chained to a fixed check.

They give you inflation protection. If interest rates rise, your maturing short-term bonds can be reinvested at a higher interest rate. That will preserve some of your purchasing power. Unlike the owners of long-term bonds, you’re not chained to a fixed check.

They protect you against the need to sell bonds before maturity, perhaps at a loss. With the right mix of bonds, you always have some that are reaching their maturity date. That gives you fresh cash to use.

They protect you against the need to sell bonds before maturity, perhaps at a loss. With the right mix of bonds, you always have some that are reaching their maturity date. That gives you fresh cash to use.

Historically, the total return on intermediate bonds—changes in principal plus interest—has been just as good as that on long-term bonds. Intermediates do a little better when inflation rises; long bonds do a little better when inflation falls. But the differences even out. So you can pursue this strategy without feeling that you’re losing capital on the deal.

Here’s how to carry it out:

Buy bonds with maturities of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years—all the way up to 10 years. That’s called laddering your investments. Altogether, your income might equal what you’d get from a 7-year bond. People with substantial assets will choose a ladder of municipals or Treasury securities, including zero-coupon Treasuries. It’s generally assembled with the help of a stockbroker or other financial adviser. People with fewer assets can build this same ladder with bank certificates of deposit (page 67).

When your one-year bond (or CD) matures, you have a choice. If short-term interest rates are uncommonly high, you can increase your income by reinvesting for another one-year term. Alternatively (and this is the usual case), long-term rates will be higher. So you’d increase your income by reinvesting in a 10-year bond. This helps offset the hole that inflation has left in your purchasing power.

The following year, your two-year bond will come due. You’ll again have a choice about where to reinvest for better returns—probably by buying another 10-year bond. Or you might fill in a particular bond maturity that’s missing.

Eventually, you will have a ladder of 10-year bonds, some of which are maturing every year. Result: a decent income plus some inflation protection. Every year you will have fresh cash in hand. If you need money, it’s there to spend. You won’t be forced to raise it by selling bonds before maturity, perhaps at a loss. If you don’t need money right now, you can reinvest for higher income if rates are up.

What can go wrong?

Being no dope, you have already spotted the crack in my ladder. If interest rates decline steeply, you lose. Every time one of your bonds matures, you might have to reinvest at a lower interest rate. In that case, you’d have been better off putting all your money in intermediate- or long-term bonds. But that’s strictly hindsight. Standing here today, you don’t know where interest rates will go.* You have to be ready for anything. The ladder gives you liquidity and choice.

Even if interest rates do decline, bond ladders don’t have to lower your income right away. In the first year, for example, you would reinvest the proceeds of your one-year bond in a 10-year bond. Assuming that 10-year rates are higher, your income might rise, even if rates in general are coming down. The risk of reinvesting at lower rates may not arise until most of your bonds are in the 7- to 10-year range.

You might include some long-term bonds to hedge against the risk of declining rates. Hold them for the rest of your life. If they have to be sold at a loss before maturity, let your heirs do it. For them, it’s free money anyway.

An alternative to laddering: buy bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs—page 785). You can get an intermediate-term ETF, paying the kind of interest rate that you’re seeking in a bond ladder. At the same time, you have liquidity: you can sell the ETF at any time, at market rates. You pay a brokerage commission when you buy an ETF, and there’s an annual fee. That compares with zero cost for a Treasury or CD ladder that you assemble yourself. On the other hand, an ETF is a onetime purchase—you don’t have to keep managing it, as you do with a bond ladder (or paying a broker to manage it for you). Your income from the ETF will vary as interest rates rise and fall.

1. Don’t put all of your money in bonds, regardless of their maturity. Going back to the table on page 719, you can see that adding stocks improves your returns while reducing risk. At older ages, you might keep 70 to 80 percent of your money in bonds, for the interest they produce, and put the remainder into stocks.

Which kinds of stocks? Income investors will probably go for equity-income mutual funds or blue-chip stocks with a history of dividend increases. But looking only at dividends is taking too narrow a view of how one can get income from stocks. Capital growth is a source of income too. As your stocks rise in value over time, sell some of the shares and spend the money. It makes sense to supplement bond interest with cash withdrawals from stock-owning mutual funds. For a simple, creative way of setting up such a withdrawal plan, see page 1142.

2. You might add some zero-coupon bonds (page 945) to the mix. The financial adviser who figured out the strategy I’m about to explain calls it his “nursing home bailout program.” Pretend you’re the client, and think about it this way.

“I’m sixty, I own my house, and statistics say I have twenty-four years to live. I want to live well.

“I’ll divide my capital into money to spend and money to save. The spending money will be deployed partly in short- and intermediate-term bonds and partly in conservative dividend-paying, stock-owning, no-load mutual funds. My savings will go into twenty-four-year zero-coupon bonds and a small amount of stock-owning mutual funds.

“Over the next twenty-four years, I will consume every dime in my spending account—all the bonds and all the mutual funds. I’ll tap the funds through annual cash withdrawals. I’ll spend a certain percentage of my bonds as they mature. I have figured out a spending rate that gives me a reasonable chance of maintaining a steady standard of living.

“If I’m still breathing after twenty-four years, I will turn to my savings stash. There my stocks will have gained and my zeros will have matured. That gives me a fresh pot of capital to sustain the remainder of my life. If I have to enter a nursing home, my stocks, my zeros, and the value of my house should pay for quality care.”

That’s what I call a creative use of bonds!

Can you ladder with bond mutual funds? No, because most bond funds have no maturity date. For true ladders, you need individual bonds or bank CDs.

But you get a similar effect by owning a combination of short- and intermediate-term funds. Leave all your dividends in the funds to be reinvested. For the income you need, make regular, fixed withdrawals from each fund, once a year or on a monthly cash withdrawal plan. The fund company T. Rowe Price offers a “Smart Ladder” through its savings bank affiliate. With a single deposit, you get a product that provides the yields a five-year CD ladder would pay.

If you don’t need to live on the income from your bonds, you can use that money to maintain the purchasing power of your capital. Here’s how:

Buy individual, high-quality, intermediate-term bonds—perhaps 5- to 10-year Treasuries. They’re safe, and you owe no state or local income taxes on the interest. Reinvest every dime that you earn in more Treasury notes or in a money market mutual fund. You might pick a money fund fully invested in Treasuries, so state and local taxes won’t be due on those dividends either. If you’re in the 25 percent bracket or higher and investing outside a retirement plan, consider tax-free municipal bonds instead. One last option: buy zero-coupon bonds, maturing when you expect to use the money (page 945). Your interest will be reinvested automatically at the same rate of interest that you earn on the bond itself.

Don’t buy your bonds all at once. Buy a few of them every few months, over the next 18 to 24 months. That way, you’ll cover a range of interest rates.

With this strategy, your investment won’t grow much in real terms, but your purchasing power will be preserved.

That depends on what happens to interest rates. Yes, if interest rates stay roughly level or decline. No, if interest rates rise substantially and you hold the fund for only a few years.

But mutual funds have an ace in the hole. You can reinvest small dividend payments at the same yield as the mutual fund returns, which is better than you’d get from a money market fund. If interest rates rise and you hold long enough, these reinvestments will offset the fund’s decline in market price.

Here’s where long-term bonds come in. They’re a terrific way to speculate on the direction of interest rates.

Suppose you’re convinced that interest rates are going to drop. Remember your mantra: Falling interest rates are good. Falling interest rates mean profits. When interest rates fall, bond prices rise. To your mantra, add this corollary (no modern mantra is without its corollary): the longer the term of the bond, the bigger the profit when interest rates decline.

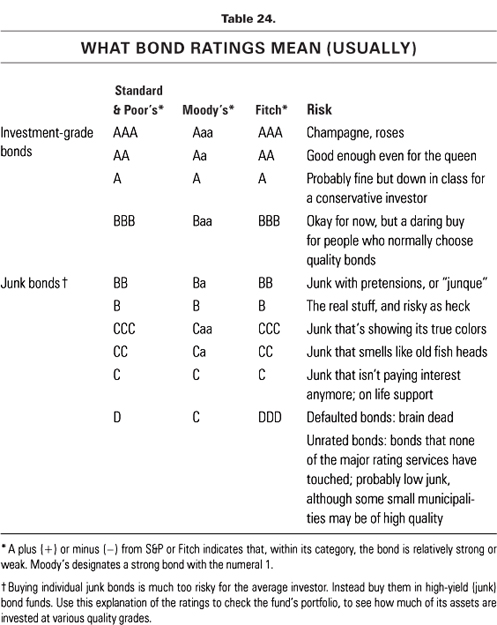

The following table shows exactly how much bigger. If you put $10,000 into Treasuries and interest rates drop one percentage point over the next 12 months, you’ll pick up only $97 on a 1-year bill—a gain of less than 1 percent. But you’d get $1,637 on a 30-year bond, for a 16.4 percent gain. The potential gain on a 30-year zero-coupon bond is a huge 34 percent. Conversely, if interest rates rise, the longer-term bonds would lose the most.

The nerviest speculators buy Treasury bonds on margin, putting up 10 percent of the cost and borrowing 90 percent. They go for zeros, where the price swings are biggest. You can make huge profits if your timing is right and take huge losses if it isn’t.

Take the 30-year zero shown in the table. Assume that you bought it on 90 percent margin, putting up 10 percent of the cost and borrowing 90 percent from your broker. If, over the next year, interest rates fell by 1 percentage point, you’d earn a 277 percent profit before costs—big-time leverage! But if rates rose 1 percentage point, you could potentially suffer as much as a 316 percent loss. (In the real world, you’d get margin calls and would probably bail out.)

Speculators should buy only Treasury bonds. Unlike corporates or municipals, most Treasuries cannot be called away from you if interest rates decline. They will pay today’s rates for 25 years or more.

Yes, but do it with exchange-traded Treasury funds. You can buy through any discount broker. In a typical market cycle, bond prices rise before stock prices

do. A speculator would swing first into long-term Treasury ETFs and then into stocks.

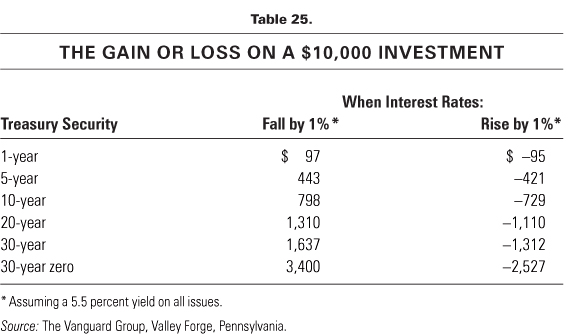

Some investors get scared every time rates pop up, for fear that they portend a drift back to double-digit price increases. But that’s not likely. From 1791 to 2007, U.S. prices rose at an annual compound rate of only 1.5 percent, and that included three periods of inflation greater than those we experienced in 1980.*

Inflationary spasms are usually followed by periods of disinflation or even deflation, when prices fall. In stable periods, long-term U.S. Treasury bonds yield around 5 percent. Here’s the record of American price changes:

Not real losers, just losers in this calendar year. If interest rates rise and your bonds show a substantial loss, you can do a tax swap that actually leaves you better off. Here’s how:

1. Sell the bonds to realize the loss.

2. Use the proceeds to buy other bonds at the market’s current, lower prices. The swap extends the maturity of the investment, and your yield to maturity drops a bit (that’s the price of the transaction). But you wind up with roughly the same interest income you had before.

3. Use the loss in bonds to tax-shelter any capital gains you took this year or to offset $3,000 of your ordinary income. Carry forward any additional losses and use them on future tax returns.

4. Be sure not to buy exactly the same bonds. If you do so within 30 days, you can’t claim the loss.

Tax-loss swapping works with exchange-traded funds, just as long as you switch to a different ETF. You can also do it with mutual funds, as long as you buy a different fund (or park your money for 30 days before buying back the same fund). You’d do such a swap only if you owned no-load funds, because they have no sales charges. Sales charges could erase any taxes you saved.

Before hustling to sell a fund, find out if you really have a loss. If you bought several years ago and reinvested the dividends, the total value of your account may still be higher than it was at the beginning.

Hold your long-term, fixed-income investments in a tax-deferred retirement account. That saves you from paying annual taxes on the interest that you earn. The full payment will grow and compound in your account. Withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income, just as they would be if you invested outside the account.

You now have (I hope) a theory of bonds. You know why you want them and how you’ll use them. The next step is to choose the bonds that will serve you best.

When buying individual bonds, always look to the credit rating (page 918). AAA and AA are top quality, while A might be called a “business risk.” BBB is on the very cusp of investment quality. One slip, and it’s junk. Unfortunately, bond ratings aren’t reliable, as we learned in the 2008 credit crash. Some AAA securities crumbled overnight. Still, they work for most issues and are the best we’ve got.

No bond is safer than a Treasury. Other bonds pay higher interest rates, but Treasuries’ strong advantages may matter more.

Treasuries, Defined. Medium-term Treasuries run from 2 to 10 years and are called notes. Minimum investment: $100. (Treasuries of 1 year or less, called bills, are generally for savers, not investors; see page 225.)

When I say that Treasuries are safe, I mean only that the interest and principal payments will always be made on time. Treasuries are exposed to the same market risk as any other bonds. If you sell before maturity, you might get more or less than you paid, depending on market conditions at the time. You have to hold to maturity to be sure of getting all your capital back.

Treasuries don’t pay as much income as other bonds of comparable maturities, but the interest is taxed only at the federal level, not by states and cities. For people in high state tax brackets, Treasuries may yield more. Most Treasuries pay fixed rates. Some of them offer inflation adjustments.

Why You Might Want a Treasury

1. You might want a bond with no credit risk. Treasuries will never be downgraded or default.

2. Treasury bonds are noncallable, at least for the first 25 years. That’s important if you’re speculating on declining interest rates and win your bet. Most corporate and municipal bonds would be called away (page 911) and replaced with lower-rate securities.

3. Treasuries are liquid. If you have to sell before maturity, you get better prices on them than on other kinds of bonds.

4. You can buy Treasuries from the Federal Reserve at www.treasury direct.gov, paying no brokerage commission. For more on buying and selling, see page 228.

The Drawbacks

1. In return for their safety and liquidity, Treasuries yield less than other bonds of comparable maturities.

2. Taxpayers in high brackets net a lower current income from Treasuries than they would from tax-exempt bonds. But you might not care in view of Treasuries’ other advantages, especially their immunity to call.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). These securities promise that inflation won’t erode your purchasing power. Whether inflation goes up or down, you get a fixed, real return. Here’s how that works:

When an issue of inflation-protected Treasuries is sold, the market sets a basic, fixed interest rate. The government credits additional interest, equal to the rise in the consumer price index. The inflation adjustment accrues semiannually and is applied to your principal. In other words, your principal grows. The fixed rate is paid on top. Your total return is the basic rate plus the inflation rate, no matter how high inflation runs.

As an example, say that new Treasuries pay 3 percent. If inflation is running at 3.5 percent, your total return would be 6.5 percent. If inflation rises to 5 percent, your total return that year would be 8 percent. After inflation, you’re always left with that real return of 3 percent.

If the consumer price index ever dropped, your bond’s principal would drop too, but never below the bond’s face value. So you also get a bit of protection against deflation.

Both TIPS and fixed-rate Treasuries are priced to cover whatever future inflation rate the market currently expects. TIPS outperform when inflation turns higher unexpectedly. To see how much inflation is built into a TIPS bond today, compare its basic, fixed interest rate with the rate on a comparable fixed-rate Treasury. The difference between the two is the forecasted inflation rate for the term of the bond.

TIPS aren’t a perfect hedge against inflation. If interest rates rise because real growth picks up, TIPS prices will fall. They’re still bonds and behave like them. If you had to sell before maturity, you’d take a loss. Prices also fell during the 2008 panic when big investors dumped TIPS to raise cash. In a hyperinflation, the semiannual adjustment of your TIPS would lag the rapid rise in the price index. Still, TIPS are as close to a pure inflation hedge as you can get if you hold to maturity. You receive a real rate of return with no credit risk.

TIPS tax alert: if you hold individual TIPS, only the basic interest rate will be paid semiannually in cash. You don’t get the inflation adjustment until you sell the bond or it matures. Even so, you’re taxed on that inflation adjustment every year. There are two ways around this: (1) Hold your TIPS in a tax-deferred retirement fund, or (2) buy TIPS mutual funds or ETFs. They distribute the inflation adjustments monthly, in the form of dividends. You can reinvest the dividends in new shares.

… Individual Bonds? Absolutely yes. You don’t need to diversify, because Treasuries carry no credit risk. So there’s no point paying a mutual fund’s annual management fee or the brokerage commission on an ETF. You can buy your Treasuries free from www.treasurydirect.gov. If you buy through a broker or commercial bank, you’ll be charged its normal sales commissions.

You can also redeem your bond through TreasuryDirect at maturity, but not before. If you want to sell early, you’d have to ask for your Treasury to be transferred to something called the commercial book-entry system, to make it accessible to stockbrokers. Anyone who expects to sell before maturity (for example, interest rate speculators) should buy through a broker or bank.

Always buy newly issued Treasuries if you can get the maturity you want. When you buy existing bonds, the bank or broker who sells them will mark up the price. Treasuries are ideal for the ladder suggested on page 921. If you don’t need current income, reinvest all the interest you earn in order to maintain the purchasing power of your capital.

If you’re buying individual TIPS, hold them in a tax-deferred retirement fund.

… A Mutual Fund or ETF? No. Funds and ETFs charge annual fees. You’ll net more money more securely by buying Treasuries individually. If you want a mutual fund invested in government-insured securities, go for one with higher yields, such as a fund that buys government agency issues, including Ginnie Maes. Don’t fall for the funds that call themselves Treasury “Plus.” They try for higher yields by pursuing fancy options programs, but they’re often at the bottom of the performance lists. If ever there were a plain-vanilla investment, it’s a Treasury bond.

One exception: consider a mutual fund or ETF if you’re buying TIPS in a taxable account. They distribute the inflation adjustment monthly, which isn’t true of individual TIPS (see above). TIPS mutual funds may also buy the inflation-protected bonds of corporations and other countries, in an effort to outperform straight Treasuries.

A Ginnie Mae is a black-box investment whose workings you and I will never see. It’s a fine, conservative bond with an appealing yield. But you have to treat it carefully. Very carefully.

Ginnie Maes, Defined. Ginnie Mae is short for Government National Mortgage Association. It’s the highest-yielding government-backed security that you can get. New Ginnie Maes often yield 0.5 to 1 percentage point more than Treasuries of comparable maturities—and they’re guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Unfortunately, it takes at least $25,000 to buy a new issue. That’s why so many investors buy their Ginnie Maes in the form of mutual funds or unit trusts (page 958).

A Ginnie Mae is a pool of individual mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration or guaranteed by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Your own mortgage might be in a Ginnie Mae. Every time you make a monthly mortgage payment, your bank might subtract a small processing fee and pass the remainder to the investors in that pool.

Each investor gets a pro rata share of every home owner’s mortgage payment. When a home owner prepays a mortgage, the investors get a pro rata share of that too.

Important! Ginnie Maes work differently from bonds. When you buy a traditional bond, each semiannual check you get is pure interest income. At maturity you get your capital back. But with a Ginnie Mae, each monthly check is a combination of (1) interest earned and (2) a payback of some of the principal that you originally invested. At the end of the term, you’ll get no capital back. It will have been paid to you already over the life of your investment.

Suppose, for example, that you get a check for $237. Of that amount, $229 might be interest; $8 might be principal. That’s an $8 bit of your original investment, returned to you. If you’re living on the income from your investments, what should you do with this check? You can spend up to $229 of it because that’s interest income. But you must save the remaining $8. If you spend that $8, you are consuming your principal, which is something that few Ginnie Mae investors understand. The statement that comes with your check will tell you how much is interest and how much is principal.

Each month, the amount of principal in your check will be a speck higher and the amount of interest a speck less. Over the term of the Ginnie Mae, you will gradually receive all your principal back. If you spend every check you get, all your principal will be gone. Conversely, if you save every check, including the interest, you will preserve the purchasing power of your capital, after taxes and inflation.

Also important! If a broker says that the fund is “government guaranteed,” that means only guaranteed against default. Principal and interest payments will always be made on time. But the feds don’t insure your investment result. How much money you make on a Ginnie Mae, or a Ginnie Mae fund or unit trust, depends on investment conditions and how wisely you buy.

Why You Might Want a Ginnie Mae

1. You like its high current yield and its government-backed protection against default. Unlike Treasuries, Ginnie Maes are fully taxable by state and local governments as well as by the federal government. So you might choose them for the “safe” portion of your tax-deferred retirement fund. They’re also worthwhile in states that have no income tax.

2. If you’re living on your savings, Ginnie Maes deliver attractive income. They’re especially good for people in low brackets who pay little or no income tax.

The Drawbacks for Investors in Individual Ginnie Mae Bonds and Unit Trusts. (The following list of risks is formidable, but plunge on. It has a happy ending.)

1. The size of your check varies every month, depending on how fast the mortgages are prepaid. This can disconcert an income investor. Some months you get more, some months you get less.