Work up a personal investment system. What kinds of properties do you intend to specialize in? (Specialists do better than generalists.) For some overlooked approaches, see page 992.

Work up a personal investment system. What kinds of properties do you intend to specialize in? (Specialists do better than generalists.) For some overlooked approaches, see page 992.Finding the Properties That Pay

Everyone said, “You can’t lose money in real estate

because they’re not making any more of it.”

Hmmmm. Where did everyone go wrong?

Of all the nonsense written about estate, the looniest says that it’s a good long-term buy because they’re not making any more of it. Of course they are. Builders put up new condominiums and housing developments. Big tracts of land are chopped into small ones. Run-down neighborhoods are rehabbed. Or, as in 2007–2009, a tidal wave of foreclosures overwhelms the market with properties for sale. If you invest in residential estate—the favorite of small investors—all these properties become your competitors. When too much new real estate gets made, prices fall.

After a housing bust, you might think that high-profit properties are stacking up in the streets, waiting for investors to buy them for a song. Buy now, hold, rent while you’re waiting, and sell when prices jump back up.

Think again. Property is more reasonably priced than it was in 2006, but that doesn’t mean you can easily make money on it. Investing in real estate—true investing—is a professional’s game. It runs on cash flow, not on the gamble of selling the property for more than you paid. The amateurs who made money in the late 1990s and early 2000s did so by accident. The real estate boom lifted dumb investments as well as smart ones. Then it dumped the dumb ones into a sinkhole. It’s always possible that you might catch another real estate wave, but that’s speculating, not investing. If your game plan relies on prices going up, buy real estate mutual funds. Don’t get your fingernails dirty.

To make money in real estate, strategically, you have to accomplish one of two things: (1) Buy the property at a true bargain price—meaning less than a typical discount from the Realtor’s listed price, including the listed price of a foreclosed property. Or (2) upgrade the property to a higher use (hence a higher value). Successful investors find many ways of doing this. You’ll find several of their strategies starting on page 987.

Before I go there, I want to say a word about two strategies that usually fail. They’re highly popular with individual investors, so I want to discuss them before getting down to serious business.

There are two easy ways.

The most popular loser is the single-family rental house. You buy a house with a rent that won’t cover its carrying cost—and that’s almost every one of them, including houses bought out of foreclosure. You dip into your pocket to help cover the expenses, expecting to earn your money back, and more, by selling at a much higher price. This strategy worked fine from the late 1990s through 2006, when speculation lit a firecracker under housing values. But those gains have gone south. Even if home prices drift gently up—say, at 3 percent a year—most rental houses aren’t good deals. After expenses, you’d probably do better with nice, quiet Ginnie Mae bonds (page 931). And Ginnie Maes never call to complain that the windows leak or the bulb in the back hall burned out.

You run into the same problems with rental condominiums, and there you’ve got a double risk. They get overbuilt fast, in popular condo areas, and seem to attract more speculators. In a poor market, a huge number of units can suddenly be for sale, dragging down prices or, almost as bad, preventing them from going up.

You might find a house whose rents exceed your mortgage payments and other expenses in one of the cities hardest hit by real estate bust. If the property offers a double-digit capitalization rate, jump on it (for how to calculate capitalization rates, see page 1001). But packs of other investors are looking there too, which means that you probably won’t get a bargain price. You might even have to lower your rent to compete with all the other new rental properties on the market. Cash returns in the area of 3 to 6 percent aren’t worth the risk you take or the effort you put in.

The other popular strategy that rarely works is the “cosmetic” fixer-upper. You buy a house with a few minor problems and put some money into repairs. A few months later, you try to resell at a higher price. But every investor is looking for that same perfect fixer-upper, so you don’t get a bargain on the purchase price. To make money after makeover expenses, you’ll probably have to price it higher than similar houses in the neighborhood. As a result, you won’t find a buyer right away, especially in an area with a high foreclosure rate. Months, or a year, could pass. To pick up some money, you’ll eventually take a tenant whose rent won’t cover your carrying costs. That brings you back to the failed strategy I mentioned first.

As long as you sell for more than you paid, it feels as if you came out ahead. That will encourage you to get into another terrible real estate deal. So do yourself a favor and find out the truth. Determine what you really made or lost on any venture you tried in the past, taking figures from your tax returns. Count all the expenses, including capital expenditures and transaction costs. Add in the value of your time (an expense you wouldn’t have if you simply bought Ginnie Maes) and state your profits as an annual compounded rate of return. Even your boom-time gains were probably lower than you think. How would you have done without the luck of a once-in-a-lifetime real estate bubble?

Going forward, resolve not to buy into any new property without a businesslike projection of what it will take to make an acceptable profit.

Active real estate investing is a part-time or full-time job. You’re a deal maker, an entrepreneur. You’re running your own small business. The successful investor will:

Work up a personal investment system. What kinds of properties do you intend to specialize in? (Specialists do better than generalists.) For some overlooked approaches, see page 992.

Work up a personal investment system. What kinds of properties do you intend to specialize in? (Specialists do better than generalists.) For some overlooked approaches, see page 992.

Spend a lot of time looking at the kinds of properties that interest you. You might do 1 deal for every 50, or 100, or 1,000 you consider. You won’t actually visit 1,000 properties, but you might look at 1,000 deeds in the courthouse. If even reading that sentence bores you, forget active real estate investing. Buy real estate mutual funds instead.

Spend a lot of time looking at the kinds of properties that interest you. You might do 1 deal for every 50, or 100, or 1,000 you consider. You won’t actually visit 1,000 properties, but you might look at 1,000 deeds in the courthouse. If even reading that sentence bores you, forget active real estate investing. Buy real estate mutual funds instead.

On a rental property, nail all the operating costs—not just mortgage, taxes, and insurance but also advertising for tenants, repairs, utilities, trash hauling, maintenance of all kinds, reserves for repainting and replacements, fix-up costs between renters, loss of rent during those periods, minimal cosmetic improvements (to maintain the property’s value and make it rentable), and a dozen other things. Costs are so high compared with rents that you’ll have to buy at a spectacularly bargain price to make this deal work.

On a rental property, nail all the operating costs—not just mortgage, taxes, and insurance but also advertising for tenants, repairs, utilities, trash hauling, maintenance of all kinds, reserves for repainting and replacements, fix-up costs between renters, loss of rent during those periods, minimal cosmetic improvements (to maintain the property’s value and make it rentable), and a dozen other things. Costs are so high compared with rents that you’ll have to buy at a spectacularly bargain price to make this deal work.

Develop strict financial criteria to identify properties worth buying. For example, you should have rules for how much you’ll pay for a property—any property—relative to its fix-up costs, rents, and expenses (page 1001) and rules for the minimum projected profit that you’ll accept. Investors who fail either lack sound criteria or lack the discipline to follow them. It does no good to buy the best property you can find if it doesn’t meet your financial criteria. Don’t grade on a curve! As one developer told me, “You make your money when you buy, not when you sell.” Your number one criterion: buy only properties that you can get for at least 20 percent below what you believe is their current market value. That’s not an easy job, but true real estate investing isn’t easy and never was. It only looked that way because, during the boom, so many people made money by accident. To get a big discount, you’ll have to search for sellers yourself. Lowball offers through real estate brokers rarely work.

Develop strict financial criteria to identify properties worth buying. For example, you should have rules for how much you’ll pay for a property—any property—relative to its fix-up costs, rents, and expenses (page 1001) and rules for the minimum projected profit that you’ll accept. Investors who fail either lack sound criteria or lack the discipline to follow them. It does no good to buy the best property you can find if it doesn’t meet your financial criteria. Don’t grade on a curve! As one developer told me, “You make your money when you buy, not when you sell.” Your number one criterion: buy only properties that you can get for at least 20 percent below what you believe is their current market value. That’s not an easy job, but true real estate investing isn’t easy and never was. It only looked that way because, during the boom, so many people made money by accident. To get a big discount, you’ll have to search for sellers yourself. Lowball offers through real estate brokers rarely work.

Learn how to project a property’s probable compounded annual rate of return. It’s not enough to say, “Wow, I’ll net three thousand dollars a month.” That might come to only a 3 percent return on the capital you invested. At that rate, you might as well keep your money in the bank. If you don’t have a financial calculator, get one and learn how to use it.

Learn how to project a property’s probable compounded annual rate of return. It’s not enough to say, “Wow, I’ll net three thousand dollars a month.” That might come to only a 3 percent return on the capital you invested. At that rate, you might as well keep your money in the bank. If you don’t have a financial calculator, get one and learn how to use it.

Have a large enough line of bank credit to carry a good investment through a bad market or a period when it cannot be rented. Otherwise you may be forced to sell at a giveaway price.

Have a large enough line of bank credit to carry a good investment through a bad market or a period when it cannot be rented. Otherwise you may be forced to sell at a giveaway price.

Look for properties that my friend Jack Reed* calls lepers. Neither the seller nor other potential buyers see any extra value in them. But thanks to your X-ray vision, you do. You’ll find some leper strategies below.

Look for properties that my friend Jack Reed* calls lepers. Neither the seller nor other potential buyers see any extra value in them. But thanks to your X-ray vision, you do. You’ll find some leper strategies below.

Buy for at least 20 percent less than current market value. That means finding a seller who’s in a hurry, doesn’t see the value hidden in his or her property, or doesn’t want to go to the effort of mining it. When prices are falling, you can’t be certain of current value, making your job even harder.

Buy for at least 20 percent less than current market value. That means finding a seller who’s in a hurry, doesn’t see the value hidden in his or her property, or doesn’t want to go to the effort of mining it. When prices are falling, you can’t be certain of current value, making your job even harder.

Bargain properties have to be flipped—that is, fixed and resold immediately—to achieve the highest return. But be warned that flips don’t always work out. You may misjudge the property and overpay. When the property is vacant, vandals may strike. A buried heating oil tank in the yard may have sprung a leak, socking you with a cleanup cost. And that’s just the start of the stories I’ve heard. The most successful flippers appear to be real estate brokers and the people who invest with them. Their line of work helps them find bargain properties. When the property’s problems have been solved, their own salespeople stand ready to market it.

Bargain properties have to be flipped—that is, fixed and resold immediately—to achieve the highest return. But be warned that flips don’t always work out. You may misjudge the property and overpay. When the property is vacant, vandals may strike. A buried heating oil tank in the yard may have sprung a leak, socking you with a cleanup cost. And that’s just the start of the stories I’ve heard. The most successful flippers appear to be real estate brokers and the people who invest with them. Their line of work helps them find bargain properties. When the property’s problems have been solved, their own salespeople stand ready to market it.

Buy property that can be upgraded profitably (zoning change, subdividing, renovation). These things take time, which means that you have to be able to pay the carrying costs—often for longer than you thought. The longer you have to hold, the higher the selling price you need to achieve your profit goals.

Buy property that can be upgraded profitably (zoning change, subdividing, renovation). These things take time, which means that you have to be able to pay the carrying costs—often for longer than you thought. The longer you have to hold, the higher the selling price you need to achieve your profit goals.

Don’t rely on future marketwide appreciation for making money. If real estate prices rise, fine. But that’s not what your strategy should depend on. Anything can happen during these postcollapse years: more recession, high inflation, rising interest rates, falling rents, falling prices, or, by some miracle, stability. Your business plan should provide for ways to make money even in a flat or declining market, thanks to a solid cash flow. As long as the property is earning enough, you can afford to wait until values rise.

Don’t rely on future marketwide appreciation for making money. If real estate prices rise, fine. But that’s not what your strategy should depend on. Anything can happen during these postcollapse years: more recession, high inflation, rising interest rates, falling rents, falling prices, or, by some miracle, stability. Your business plan should provide for ways to make money even in a flat or declining market, thanks to a solid cash flow. As long as the property is earning enough, you can afford to wait until values rise.

To succeed, you have to buy a property with upgrade potential or at a bargain price, not just a nice-looking property sold by a Realtor at an everyday price. Assuming that you follow through on those criteria, here are some strategies to try:

Homes and apartment houses there are far less likely to be overpriced than they are in the classier sections of town. And working-class homes rise just as much in percentage value, maybe even more.

These could occur during a recession or after a plant closing, assuming that jobs are likely to return.

Maybe asbestos was blown onto the ceiling. Maybe the foundation has dropped four inches and the floors tip. Whatever the problem, investigate the cost of solving it, then offer a low enough price to make the repair and guarantee yourself a substantial profit. The seller may accept, just to get the monster off his or her hands. (This strategy, incidentally, is a variant on buying a house that needs only cosmetic repairs. By going beyond cosmetics, you can truly get a bargain price—at least 20 percent under current market value minus cost of repairs.)

Look for a detached house, not a condominium. There aren’t many of these, but they’re dandy investments. They sell cheaply because hardly anyone wants to own them. They rent dear because they appeal to single people and childless couples. If the house has an enclosed space that you can turn into a second bedroom inexpensively—an attic, a breakfast room, a sunporch, an attached garage—you may have a real winner. But check out the neighborhood before converting the garage. In some areas, houses without garages are tough to resell. And be sure that you can get the required permits.

One of them sits in the other’s backyard. Few home owners want them, so the second house goes for about two-thirds off. But most tenants don’t mind the arrangement. You get normal rents and a fine cash flow. Take a look at the profit potential in moving one of the houses to a lot of its own.

It still has to meet your financial criteria. Assume that you yourself are paying a market rent as well as a half-share of the upkeep, and see if it still yields a double-digit capitalization rate (page 1001).

This strategy works especially well when rents are sagging and real estate prices are going nowhere. It has made investors a lot of money, but there are some legal risks. First, the good part:

You put an ad in the paper reading “$4,000 moves you in” or “Buy a house, no money down,” depending on how much money (if any) you want up front. Usually it’s 1 to 3 percent of the purchase price. You then strike a deal that will let the tenant buy the property at a fixed price, usually within one to three years. The tenant pays the monthly rent plus something more, which is credited toward his or her down payment. If the normal rent is $800 a month, the lease option rent might be $1,200, with $400 put toward the purchase price. Part of the up-front payment might also go toward the price. At the end of the term, the tenant can buy at the specified price, although he or she isn’t required to.

You and your tenant-buyer sign a rental agreement and an option agreement. If the contract lasts longer than a year, consider annual increases for both the rent and the house price. Your local apartment association can supply a lease form, but there are no standard forms for the option sale. You’ll need a real-estate lawyer to draw it up.

Lease options greatly improve your cash flow by paying you more than you’d get from rents. They bring you tenants who take especially good care of the house. And you often can set a purchase price at the high end of the going range. If the tenant ultimately can’t buy, you get to keep all the extra money.

Fairness demands that you work only with tenants who will have a good shot at making the down payment and qualifying for a mortgage during the option period. It’s dirty pool to take lease option money from people who obviously won’t be able to buy. Even qualified buyers, however, often pass on the option rather than take it up.

Now the bad part: a lease option, if challenged, may be construed by a court to be a land-contract sale. Sales can lead to tax reassessments. They trigger the due-on-sale clause in your mortgage, giving the lender the option of ordering you to pay off the loan (lenders rarely hear or care about lease options, but they might). As a practical matter, these and similar risks are rarely encountered. Still, you should know they’re there.

You own a little more land than the zoning requires but not enough to subdivide into a separate building lot. Try to sell that extra sliver to a neighbor for a garage, a swimming pool, or a green space for planting shrubs and trees. You’ll still have to go through a formal subdivision.

Expensive homes generally make poor real estate investments because rents fall well short of covering your costs. On the other hand, you may find a house you really like at a good price. So here’s a strategy if you’re getting older and own several homes in the midprice range: Sell the midprice homes and roll the profits into a high-cost home that you’d eventually like to live in, using a tax-free 1031 exchange (page 1003). Rent out the high-cost home for a while. Move into it later, making it your permanent residence. You’ve preserved the profits from your other houses, tax deferred, and acquired a house that suits you fine for the rest of your life.

Here are some properties that can be flipped:

A Teardown. Buy a house or a duplex that is going to be torn down. Don’t pay any more than $1,000 for it. Hire a house mover to take it to another lot. You can generally sell the property for twice the money that you have in it (including all your expenses), if you do it right.

Absentee Owners. Do some research at the county records office. Write to everyone who owns land locally but lives somewhere else. Ask what they would sell their property for. Maybe 1 out of 200 will name a price that’s half the real value because he or she doesn’t know the going price of property in your town. That one you buy. (The flip side of this advice: if you ever receive such a letter, don’t answer it before calling a local real estate agent to find out what the property is worth.)

Tax-Sale Redemptions. In some states, former owners have a right of redemption, during a limited time, if their homes were seized for nonpayment of local property taxes and sold at auction. Call or write such people if their houses sold for substantially less than market price. They usually have several months to redeem their homes for the sale price plus interest. If that’s utterly beyond their means, you might make a deal. Put the redemption money into an escrow account; let the former owner use the account to redeem the house and sell it to you at the same low price; pay the former owner a reasonable fee for his trouble; and resell the house at full market value. (There is no flip side to this advice. For the former owner, it’s all found money. He or she might even advertise for someone to do this deal with.)

Houses sold to satisfy federal tax delinquencies carry redemption rights all over the country.

Expiring Options. Look for people who are renting a house with an option to buy at something less than the current market value but who haven’t the money to do the deal. You can buy their option, take over the house at the low option price, and resell for a higher price. Valuable real estate options are expiring all the time, unused. Where do you find them? Advertise: “We buy options to purchase real estate.” Or write to the tenants of any real estate investor who does a lot of lease option deals. Or write to tenants against whom eviction notices have been filed, to see if they had an option on the house they’re quitting. Or see if any lease option memoranda have been filed with the county clerk. Some investors buy valuable options and resell them to someone else rather than taking title to the property. You can do this deal with commercial properties too.

Tenancies in Common. A person who owns property as a tenant in common (page 85) may want out. But the other owners might refuse to sell and decline to buy the defector’s interest. That person can sometimes start a lawsuit to require a sale. But he or she may be constrained by personal considerations or else may want the money fast. In this situation, an investor can often buy the defector’s interest at a low price, then force a buyout or sale or wait until the other owner decides to sell or refinance voluntarily. You can advertise for these investments—“We buy the interests of tenants in common”—or go through deed records and compile a mailing list of tenants in common. Opportunities often arise when Great-Uncle Garrett leaves a plot of land to all three of his nephews, who hold different views on what should be done with it.

Probate Sales. Estates will sometimes (not often) sell real estate at a low price to buyers who pay cash. This usually happens when heirs are pressing for their money and aren’t using a real estate agent. To find these properties, phone or send a letter to the executors of every estate filed for probate. You might send out hundreds of letters a month, leading to one deal every three months on the terms you want.

Clouded Titles. Attorneys, paralegals, and specialists in title searches, in particular, might invest in properties with clouded titles. The owners may be glad to sell at almost any price. Buy only when you can cure the title and resell the property for full market value. But don’t buy if you’ve been advising the owner and have a fiduciary relationship, unless the owner gives up on the property. In that case, get a signed waiver releasing you from your duties and acknowledging your prior good-faith advice on how to handle the situation.

Houses Going into Foreclosure. Send a letter every 10 days to people whose houses are scheduled for foreclosure. Offer to buy immediately for cash. Not many people respond at first because they’re still hoping to save their homes. But they become more interested once they accept the inevitability of the loss. Do a thorough title search before going through with the deal. The house may be encumbered by liens. The records don’t always show how much is currently owed on the liens, so work with the owner to find out. The best foreclosure investors learn how to do these title searches themselves. Outside firms often don’t get the job done in time.

One advantage of buying from the owner is that you usually get a low price. One risk is that the owner may go bankrupt, which could tie up the house in court. Some states have laws regulating preforeclosure sales, so check yours out.

Foreclosure Auctions. Foreclosure or trustee sales are a lot trickier than people think. You normally can’t inspect the house in advance. You have to guess what it’s like inside by its exterior condition. Some angry evictees trash the interior on their way out. The house has to be worth at least 30 percent more than the mortgage against it to make your risk worthwhile. The title may not be clean. In the frenzied market for mortgage securities during the bubble, mortgages sometimes were transferred improperly from one institution to another and you’ll need to straighten out the paperwork. If there were liens on the house that the foreclosure wiped out, there’s a risk that the lien holders who are wiped out by the foreclosure will complain that they hadn’t been properly notified. If their claims are upheld, however, the deal is generally unwound with no great harm to the auction buyer. Don’t spend money on fix-up costs before making sure that no viable liens (including IRS liens) exist.

Sales normally occur on the courthouse steps. Most states require a cashier’s check in the exact amount of your bid, but some allow you to pay the owner 10 percent, to be followed soon by the whole amount. You shouldn’t pay any more than 75 to 80 percent of the fair market value, as best you’ve been able to determine it. Get-rich-quick books often tout the bargains in foreclosure sales, but professionals say that a good house is hard to find. Maybe 1 deal in 20 makes any sense. New investors should generally buy after a foreclosure or before, not at a foreclosure auction.

Foreclosed Houses Held by a Bank. They’re generally listed with a real estate agent, and you can see the inside. But these listings aren’t bargains, they’re at market price. You can offer 20 percent below market but probably won’t even get a counteroffer. Bank foreclosure departments aren’t marketers, they’re owners trying to get a good price, and the real estate agents won’t push them on your behalf. But keep offering. If the property continues not to sell, consider dropping your offer to 25 percent below market (houses lose value when they sit unoccupied). One day the bank may suddenly say yes. Investors get perhaps 1 out of every 25 properties they pursue this way, but that house will be a bargain.

Another option is to follow the foreclosure sales to learn which lenders end up owning particular properties you like. Try to call the bank officer in charge of those properties and offer 20 percent below market value. Because of the foreclosure glut, the officer might not take your call, referring you to a Realtor instead. If you do get someone on the line, describe the property, its condition, and the length of time it has been on the market, and offer 20 percent below market value. The officer will generally say no. Again, keep offering. You never know when you might get a yes, and in-person offers may work better than going through a real estate agent. Incidentally, if the bank says that a property has been sold, ask if the deal has actually closed. If not, keep calling. Sometimes those sales fall through.

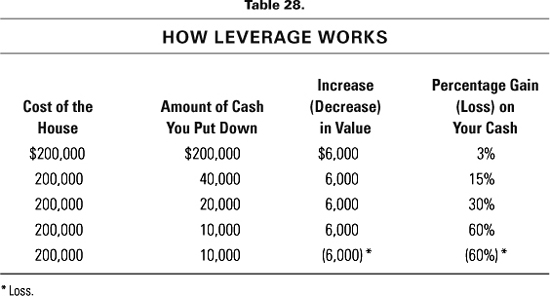

Real estate returns—both profits and losses—are greatly magnified by leverage, defined as the amount of cash you put toward the down payment compared with the property’s price. The less cash you put down, the larger your mortgage and the higher your leverage. High leverage gives you more potential for profit if prices rise. Conversely, if prices fall, the higher your leverage, the larger your percentage loss.

Gains in market value (if any) are the sideshow. If you’re hoping to flip the property, you have to reduce the gain by the money you spent on mortgage interest, insurance, taxes, fix-up costs, and selling expenses. If you’re planning to rent, you need to look at the cash flow, which is the income you get from the property after all outlays for operating expenses, mortgage payments, and capital expenses such as replacing a roof. The lower your down payment, the bigger your mortgage and the larger your monthly payments. Even with a traditional down payment of 20 percent, it’s almost impossible to cover all your costs with

rents. You’ll have negative cash flow, meaning that you’ll be reaching into your pocket each month to help support your investing habit. If you put the minimum down, your cash flow problem is even worse. What happens if you lose your job or are forced into early retirement? If your salary was supporting your real estate investment, you may have to sell the property fast, maybe for 10 to 15 percent less than its actual value. When you have a big mortgage to repay, your profits may evaporate or turn into a loss.

The wise investor arranges for rents to cover his or her costs. Working backward, that almost always means buying the house at a bargain price. No bargain, no worthwhile profit over the long run.

Before buying any rental property—a single-family home, a duplex, a fourplex—ask yourself: Do I have the guts to evict? To demand the rent on time? To demand the rent at all if someone gives me a sob story? Can I throw out an illegal pet? A sweet mutt adored by a four-year-old? With cancer?

If you can’t answer all these questions with a hard-boiled yes, don’t even try to be a landlord. In this game, nice guys get their clocks cleaned. You may set out to be the first decent landlord in history and discover too late that you were merely incompetent. Buying any sad story, from any tenant, could cost you not only your profit but your principal and your credit rating too.

I don’t mean to be harsh on tenants, having once been one myself. Most tenants are fine. They take care of your property and pay on time. Other tenants start out fine, then turn into monsters. They bounce checks. Make excuses. Break rules. When it becomes clear that you’re going to evict, they may sell your stove and refrigerator, break all the windows, and punch holes in the walls.

Before even getting into this business, rent the movie Pacific Heights to see how bad landlording can be. It’s only a mild exaggeration. Deliver an eviction notice if the rent is two days late. A salvageable tenant may be furious but will pay on time from that day forward. Bad tenants you want out sooner, not later. Good tenants won’t be late, ever, unless by an honest mistake. An eviction notice will annoy them too, but they’ll apologize.

Never take tenants without checking them out: a credit check, personal calls to the tenants’ past two employers, and personal calls to the past two landlords, asking if they’d rent to these people again. (The current landlord might lie, just to get rid of them.) Insist on cash or money orders for the security deposit and the first month’s rent; that gets rid of people who give bum checks and will hold the apartment until you can evict them. If bad tenants slip through your screen, move against them decisively. Enforce all rules to the letter. Demand cash or money orders from anyone who ever bounced a rent check. Evict anyone who violates the lease. Grrrrr. If you think I’m being overly harsh, you’re a landlord newbie.

Some home owners try to sell and can’t (or can’t sell for any price they will accept). So they move to a new house and find tenants for the old one. What happens?

If you have a recent mortgage, you probably can’t charge enough rent to cover your expenses. So the house will keep on leaking money, although not as much as it would if it were vacant. As long as you’re charging a fair market rent, you get a small tax break: all rental expenses, including depreciation, can be written off against rental income and, in some cases, against other income too (page 1002).

Don’t let the house become a permanent rental! If that happens, you will owe a capital gains tax on the property when you sell. How do you hang on to the status of “temporary” landlord? Keep offering the house for sale, don’t give a lease, and pray that you won’t have to rent it for very long. Best advice: (1) Don’t get into this box in the first place. Owning two homes can be Bankruptcy City. Sell your own house before buying another. If you take a new job in another city, live in a rented room until your house is sold, even if it means leaving your family behind. It’s the lesser misery. (2) Sell on a lease-to-own option (page 990). You can usually strike a fair deal with an individual buyer who will pay a fair rent plus something extra toward the down payment. A professional real estate investor, however, who’s aware of your anxiety, might offer only rent and demand that the entire payment go toward the purchase. Whatever you decide, try not to let the option run for more than a year or two. Never sign a lease option contract without the advice of an attorney who specializes in real estate. (3) Slash the price on your unsold house, just to get rid of it. It might be worth selling for less than its mortgage value if you have enough savings to cover the remaining debt. The amount you’re earning on your savings may be less than the carrying costs on the house.

Generally speaking, it’s not smart to buy land and sit on it, waiting passively for its price to rise. Prices may rise slowly, and in the meantime empty land devours money. You’ll owe real estate taxes and maybe loan interest if you financed your purchase with the seller. There’s almost never any rental income. (If it’s a meadow, maybe you can get a farmer to hay it.)

Owners of raw land also face enormous political risks. For example, your town might decide that it’s growing too fast and downzone your land from commercial to residential, or from multifamily to single-family use, or to a green space. That sharply reduces your property’s value. Or a new town environmental officer might declare part of your property a wetland, which virtually prevents its use as a building lot. In some parts of the country, you may be unable to get water rights. Anything can happen to a piece of raw land, and most of what can happen is bad.

When a land deal is good, however, it is often very, very good. Consider investing when:

You have reason to believe that you can, within a reasonable period, make the land more valuable. For example, you might subdivide it into building lots, get its zoning upgraded to higher-density use, or get a road approved for a plot that was previously inaccessible. Any of these changes will raise the land’s value.

You have reason to believe that you can, within a reasonable period, make the land more valuable. For example, you might subdivide it into building lots, get its zoning upgraded to higher-density use, or get a road approved for a plot that was previously inaccessible. Any of these changes will raise the land’s value.

You believe that you have some inside information about where roads will go or where a major company plans to move. In real estate, it is usually legal to trade on such tips. Your risk is that the tip was wrong or that, though right, it didn’t affect the value of your property.

You believe that you have some inside information about where roads will go or where a major company plans to move. In real estate, it is usually legal to trade on such tips. Your risk is that the tip was wrong or that, though right, it didn’t affect the value of your property.

You can buy on an option. With an option, you pay the owner for the right to purchase the land, at a stated price, within a certain number of months or years. During that period, you do the rezoning or subdividing and line up a buyer. Then you take possession of the land or assign the option to your buyer. If your plans don’t work out, however, your option will expire. The landowner gets to keep both the improved property and your option money.

You can buy on an option. With an option, you pay the owner for the right to purchase the land, at a stated price, within a certain number of months or years. During that period, you do the rezoning or subdividing and line up a buyer. Then you take possession of the land or assign the option to your buyer. If your plans don’t work out, however, your option will expire. The landowner gets to keep both the improved property and your option money.

The checklist is long. Can you build on the property? What are the town’s environmental rules? What’s the current zoning? How will water and electricity get to the site? Where will the town allow roads to be built? What about sewage systems? Can foundations be dug, or will a developer have to blast or pound in pilings to reach deep bedrock? Where does the town stand on development, politically? How fast does the planning board act on proposals brought before it? Arm yourself with a good local real estate lawyer. If you plunge into raw-land development, you are going to need one—especially one who knows the territory.

Any real estate investor—from the owner of a single-family house to a major-league developer—potentially faces huge liabilities under the rapidly changing laws on environmental protection. You may say, “I have no problem with my property.” But a year from now a new substance may be found to cause cancer and be added to the government’s “horribles” list. Surprise! That substance may be in your roof. Unless you replace the roof, your investment will lose value.

You think this far-fetched? Consider the retired California couple who invested in a mortgage on a pear orchard. The borrower defaulted, and they foreclosed. Two fuel tanks were found buried on the property. To start, they had to pay $30,000 toward the cleanup, and the state could force them to spend $100,000 more. And consider the Indiana home owners who lived near an area where the state stored road salt. The salt got into the groundwater and contaminated the wells. The water was drinkable, but the home owners’ pipes and appliances corroded. Their property values plunged.

And consider that nice piece of land you just bought. Fifty years ago, it might have been the site of a factory that left toxic chemicals in the soil. Or tomorrow night two guys in dark clothes may use it as a dump for leaky drums of industrial waste, leaving you financially liable and responsible for the cleanup. You’re also in trouble if you own a building that’s found to have asbestos or lead paint in it. The law may not force you to remove it. But few people will buy or finance the building as long as the asbestos is there, so your investment has been damaged.

Professional investors won’t buy a commercial property anymore without first getting an environmental audit. The auditor tests the property for buried oil tanks, chemicals, pesticide residues, asbestos, and other substances that impair its value. Individuals should get audits too, especially if you’re buying open land, land next to an old gasoline station, a commercial or industrial property, farmland, or an apartment building. In fact, your lender may require it. Probable price range for small investors: $500 to $30,000, depending on the property. Before rejecting the expense of an audit out of hand, think what you’d lose if you bought a contaminated piece of real estate that had to be cleaned up.

Three other reasons to check for toxic waste: (1) If you buy a property and waste crops up later, you may not be forced to pay for the cleanup as long as you made “all appropriate inquiry” before buying. “Appropriate” hasn’t been defined, but an audit should do it. (2) Even if the government has to pay for cleaning up your property, it might not do the job for years. In the meantime, you’re holding an asset that can’t be sold for anything close to what you paid. (3) Anyone who buys your property will probably subject it to an environmental audit. If wastes are found, it may kill the deal and will certainly reduce its price.

In short, the risks of investing in real estate have risen sharply. The average investor has not yet caught up with these new environmental dangers, which could wreck any deal you do.

Total Awareness, All the Time. You should follow real estate constantly, tracking the ever-changing political and financial risks. The new environmental hazards, for example, might persuade you to lean toward the shorter-term investing ideas. Some investors don’t even want their names on a chain of title, lest they get hit for part of a property’s cleanup costs. So they’re finding ways to trade property interests without ever owning the real estate themselves. One idea: options. You can trade them without taking title to anything.

Patience. You may have to look at dozens of properties in person, and hundreds on paper, to find one that meets your investment specifications. Many a seller is lying in wait for an idiot who will overpay.

Tough-Mindedness. You have to be firm with tenants, firm with buyers, firm with sellers. Not mean, but firm. Real estate investing is a deal-making, business-to-business world with fewer rules than the average consumer is used to. Consumer laws provide some protections when you buy a house to live in but not when you buy one to rent out. That’s why your investment criteria are so important, as is your discipline in following through.

Flexibility. A truly superior investor brings his or her technical knowledge of real estate contracts and finance to bear on a single critical point: the special needs of the person on the other side of the deal. What can you give him or her to secure the terms you want? If there’s no way to reach your minimum requirements, bow out. Never do a deal just to do it or because you’ve already put in a lot of time.

Quick Decision Making. When you first think about real estate, take a lot of time to study up. Read some books on real estate finance. Learn about local property values. Analyze your area’s economy: Are jobs and people moving in or out? Check the environmental hazards. Choose some investment niches to investigate. Set some yardsticks for yourself (page 1001). But once you step into the arena, be prepared to move quickly. No one leaves money lying on the table for very long. If you have to think and think and think and think about it, someone else will buy. The best deals go the fastest. You should buy the first acceptable deal (one that meets your criteria), not keep prowling for the “best” one.

An Iron Gut. In almost every deal, something goes wrong. Rehab estimates are off. Somebody dies. The town passes new laws that change the rules. Your lender reneges. The seller tries to change the terms. A tenant sets fire to an apartment. Most of the problems can be worked through. But it will take time, your nerves will fray, and you might not make as much money as you thought. That’s how real estate investing goes. If you can’t handle the drama, buy Ginnie Maes.

Time. Direct investing in real estate is a part-time or full-time business. To make money, you have to be personally involved: inspecting properties, evaluating prices, negotiating, arranging for tenants, seeing to repairs, going to zoning hearings, lining up financing, living your deal in a dozen ways. If you don’t have the time, don’t even think about trying to buy.

Clear Financial Yardsticks. Before you begin your real estate investment career, draw up some yardsticks for yourself. Measure every opportunity against them. If they fit, follow up. If they don’t, move on. Find out quickly if a deal falls within your financial parameters, so you won’t waste your time on something that can’t produce a large enough return. These yardsticks will change as you gain experience, but they should always be written clearly on your cuff. They act as a discipline against the all-too-human tendency to buy that pretty house or lot just because it’s there.

No set of financial parameters fits every investment or every investor. But here are some guidelines to start with:

A rental property will work only if you bought it at a bargain price (20 percent under current market value) or you create value by rescuing a problem property. Buying at market price, just to rent, doesn’t give you decent returns. Neither does buying at market price and making ordinary improvements.

A rental property will work only if you bought it at a bargain price (20 percent under current market value) or you create value by rescuing a problem property. Buying at market price, just to rent, doesn’t give you decent returns. Neither does buying at market price and making ordinary improvements.

Don’t make improvements to a house or building you own unless you can get $2 of increased market value out of every $1 you spend. You need to fix up a fixer-upper, but by just enough.

Don’t make improvements to a house or building you own unless you can get $2 of increased market value out of every $1 you spend. You need to fix up a fixer-upper, but by just enough.

On rental properties that you plan to hold, focus on the capitalization rate, which is the rate of return on your invested capital. You have a 10 percent cap rate if your net operating income comes to 10 percent of the price of the property. (Net operating income is the rental income from the property minus expenses such as insurance and repairs but before mortgage payments.) Many buyers go with low cap rates of 4 or 5 percent, counting, for their profit, on the property’s future rise in value. But those are poor investments. Tougher-minded buyers won’t accept cap rates lower than 10 percent and preferably 12 percent.

On rental properties that you plan to hold, focus on the capitalization rate, which is the rate of return on your invested capital. You have a 10 percent cap rate if your net operating income comes to 10 percent of the price of the property. (Net operating income is the rental income from the property minus expenses such as insurance and repairs but before mortgage payments.) Many buyers go with low cap rates of 4 or 5 percent, counting, for their profit, on the property’s future rise in value. But those are poor investments. Tougher-minded buyers won’t accept cap rates lower than 10 percent and preferably 12 percent.

Given all the risks in rental real estate, you should be shooting for a combined annual return of 25 percent, in upgrading and/or bargain-purchase profits, marketwide appreciation, amortization, cash flow, and tax savings. To calculate a one-year rate of return, add the dollar amounts of those six items and divide by the money you invested, including the value of your acquisition time. There are fancier ways of calculating returns, but for individuals, this will do.

Given all the risks in rental real estate, you should be shooting for a combined annual return of 25 percent, in upgrading and/or bargain-purchase profits, marketwide appreciation, amortization, cash flow, and tax savings. To calculate a one-year rate of return, add the dollar amounts of those six items and divide by the money you invested, including the value of your acquisition time. There are fancier ways of calculating returns, but for individuals, this will do.

Bargains are measured by the discount you can get from current market value. Professionals demand discounts of at least 20 percent. If they can’t get that price on a particular deal, they move to the next one.

Bargains are measured by the discount you can get from current market value. Professionals demand discounts of at least 20 percent. If they can’t get that price on a particular deal, they move to the next one.

Have an exit strategy. That’s one of the big differences between professionals and amateurs. Amateurs buy with dreams of profit in their heads. When professionals buy, they already have a plan for getting out. Specifically, they need to see a way of reselling almost immediately for a profit. Their plans don’t always work out, but quick resale should be a reasonable possibility. If you buy at a bargain price because the house has a cracked foundation, for example, a repair should get it right back on the market at a sizable increase in price.

Have an exit strategy. That’s one of the big differences between professionals and amateurs. Amateurs buy with dreams of profit in their heads. When professionals buy, they already have a plan for getting out. Specifically, they need to see a way of reselling almost immediately for a profit. Their plans don’t always work out, but quick resale should be a reasonable possibility. If you buy at a bargain price because the house has a cracked foundation, for example, a repair should get it right back on the market at a sizable increase in price.

All things being equal, invest close to home, in neighborhoods you know—but only if prices are reasonable there. If they’re not, you have two choices: forget about real estate or buy in another part of the state or the country where you think you can make a profit. Long-distance rental-property ownership is feasible as long as you have some local help, although local help raises your costs. Real estate investing requires a close understanding of the pertinent laws in the state you choose.

All things being equal, invest close to home, in neighborhoods you know—but only if prices are reasonable there. If they’re not, you have two choices: forget about real estate or buy in another part of the state or the country where you think you can make a profit. Long-distance rental-property ownership is feasible as long as you have some local help, although local help raises your costs. Real estate investing requires a close understanding of the pertinent laws in the state you choose.

You Can Deduct Your Rental Costs, including depreciation, against your rental income from this and similar projects, within the limits allowed for passive losses (see page 607). Any excess expense can tax-shelter some of your regular income if you meet the income test. If you don’t, all your unused tax deductions are allowed to accumulate. You can use them against taxable rental income in future years or to reduce the size of your taxable profit when you finally sell this or another investment property.

Investors in Raw Land Get Virtually No Deductions because land isn’t depreciable. If you borrowed money to buy the land, you may or may not be able to write off the interest. Such interest can normally be deducted only if you own the property for trade or business; or, if it’s an investment, only against income from other passive investments, such as stock dividends or the sale of a rental property. The interest on loans of up to $100,000 become deductible, however, if you borrowed on a home equity line of credit.

You Can Defer Paying Taxes When You Dispose of an Investment Property by doing a 1031 tax-free exchange. Instead of selling the property, you exchange it for another one. You don’t even have to do a direct two-way swap. You can set up a three-cornered trade (or more). For example, suppose you want Jennie’s property, Jennie wants Cipa’s, and Cipa wants Lynn’s. You can each deed the house to the proper person, noting that the agreement is part of an overall plan to accomplish an exchange. Get help from a professional to do this right.

If You Don’t Do a Tax-Free Exchange, You May Have a Taxable Gain Even if You Sell at a Nominal Loss. That’s called a phantom gain. The depreciation deductions reduce your adjusted basis* in the property. You have a gain if you sell for more than your adjusted basis, even if it’s less than you originally paid.

A second mortgage (mortgages are called trust deeds in some states) is a second loan against a home. It makes a tempting income investment because it pays a lovely yield and normally doesn’t require property management, as direct real estate investing does. But you face huge risks if the borrower defaults.

When you buy a second mortgage, you are betting that the borrower is going to make his or her payments on time—as, in fact, most do. You advertise for these loans (“We buy second mortgages”) or find them through real estate brokers and lawyers. They are usually bought at a discount from face value in order to increase your yield.

Before buying, put the borrower through a credit and employment check (don’t count on the broker to do it for you). Some of these borrowers are perfectly sound, but others are flakes whom normal lenders wouldn’t touch.

You want a loan that comes due within a short period—say, two or three years. It should be collateralized by real estate, usually by the property itself. The borrower should have substantial equity in the property and a history of making all payments on time. In general, the house should be worth at least 30 percent more than all the loans against it. Raw land should be worth at least 60 percent more because of the risk. Many investors won’t buy second mortgages against raw land.

If the borrower defaults, he or she will probably default on the first mortgage too. If the first mortgager forecloses, your interest will almost certainly be wiped out. You might have to make monthly payments on the first mortgage yourself while you wait for the house to be sold, or bid on the house at the foreclosure auction yourself, in order to salvage your investment. Talk about these risks with a real-estate attorney before getting into second mortgages. Attorneys often invest in mortgages themselves, because they understand the process. Anyone who buys into second mortgages should have a substantial personal income or a large pool of assets, to support the investment if something goes wrong.

In most cases, no—you can only get poor. Poor, by spending your hard-earned money on the windy, deceptive books and tapes they flog. Poor, if you try to follow their half-baked schemes, which will cost you money with small chance of reward. Really poor, if you can’t afford the deals you get into. They set you up for default and maybe even bankruptcy. Many of these “geniuses” have wound up bankrupt themselves. A few have gone to jail.

I studied a group of guru TV programs once, talked to the gurus, and got their materials. I found them misleading, fantastical, false, and, in some cases, flatly illegal. The dream they sell—that you can buy profitable property with no credit, no job, no experience, even with a bankruptcy behind you—shouldn’t pass anyone’s first-round BS test. For terrific and detailed reviews of dozens of gurus, including their books, tapes, and seminars, visit John T. Reed’s Web site at www.johntreed.com/Reedgururating.html. Some are recommended, many others aren’t. You’ve been warned.

If dealing with tenants or bidding at auction is harder work than you had in mind, consider the stocks of real estate investment trusts (REITs—pronounced reets)—or even better, a mutual fund that buys them. They’re for potatoes who want to own properties without leaving their couches.

REITs do your investing for you. They’re real estate management companies that buy, own, and manage properties that they intend to hold for the long term. They earn income from rents, leases, and the occasional capital gain.

By law (and to avoid being taxed), REITs have to pay out most of their earnings to their investors every year, in stock or cash. As a result, their yields are relatively high, attracting income investors. Be warned that dividends received from REITs are taxed in your ordinary income bracket. Dividends from other real estate stocks are normally taxed as capital gains. Qualified taxes paid on global funds, to other governments, are passed through to U.S. investors as tax credits.

Most REITs trade on a stock exchange. That means you can buy and sell at will. You’re not locked in, as you would be with a real estate limited partnership. You invest through a discount or full-service stockbroker, paying normal brokerage commissions. A REIT’s share price will rise and fall in line with its management success, dividend payouts, property values, and broader industry and stock-market trends.

Over the long term, REITs act as a proxy for the commercial real estate market. They follow a price path that’s somewhat different from that of other stocks. For this reason, investors use them as a way of diversifying their portfolios. But just because a class of stocks is different doesn’t mean that it carries less risk. When the market crashed in 2008–2009, REITs led the slide and fell further than the market as a whole. That’s the danger of investing in a single industry. Its fortunes depend entirely on how that industry performs—and in 2008–2009, commercial real estate stank. You own it because you want a toehold in this portion of the economy. When the odor of real estate improves, REIT stocks do too.

Some REITs—called unlisted, untraded, or private REITs—don’t trade on an exchange. They invest in real estate companies, and you’re expected to leave your money there for 10 to 12 years. You earn attractive dividends. At the end of the period, the sponsor will list the REIT on an exchange so that you can sell, or liquidate the properties and distribute the proceeds. Only then will you know what your investment has actually earned. If you need the money before 10 or 12 years are up, you’ll take a haircut on the price. That is, if you can get your money out at all.

You’d be wise to stay away from unlisted REITS, for several reasons. First, they’re high cost. Counting sales commissions and other fees, you’ll pay 11 to 16 percent up front. Put another way, out of every dollar you invest, only 84 cents may actually go into real estate. Second, these investments lock you in, so you give up flexibility. If you need your money early, you’ll have to accept a discount from the shares’ estimated value. The sponsor may have the right to let you out only for “hardship” reasons and to suspend redemptions at any time. Third, they harbor substantial conflicts of interest. The sponsor usually owns several companies that do business with the REIT, and at high fees. (Other REITs have conflicts too, but unlisted REITs appear to have more than most.) Fourth, you’ll have paid more fees over the years than if you had invested in publicly traded REITs, so your returns probably won’t be as good. In the end, how well you do depends on the sponsor’s exit strategy. When the REIT finally goes public, what will it be worth? Less than you’d net from public REITs.

Equity REITs are the principal object of desire—your best long-term bet for dividends and growth. They own apartment buildings, hotels, community shopping centers, regional malls, outlet centers, industrial parks, office buildings, self-storage buildings, nursing homes, mobile home parks, and other properties. Some are regional, others are nationwide, but most specialize in certain types of properties. Speculative REITs raise money for unusual types of properties, such as private prisons, or properties they haven’t even purchased yet. Blue-chip REITs are major real estate companies with long histories of superior management, rising dividends, and increasing profits. The newest direction: global REITs that invest in properties abroad.

REITs are tough for individuals to analyze. The key number is funds from operations (FFO)—generally defined as income after operating expenses and before depreciation and amortization. You want the FFO to grow. Publicly traded REITs disclose FFOs on their shareholder reports.

To check how the market assesses a REIT, compare its FFO to earnings. A high FFO-to-earnings ratio says that the REIT is expected to keep on growing at a high rate; a low ratio says it’s in trouble (although it could improve). Different types of REITs carry different ranges of ratios, and you need to know where yours fits in.

Another question: Where are the dividends coming from? Are they fully covered by FFO (as they should be), or is the REIT paying its investors by taking loans, selling properties, or dipping into reserves? If any of the latter, avoid it; the dividends may not be sustainable. An especially high yield is always suspect. It means that the REIT has dropped in price—maybe because some of its properties are failing or because its dividend may be cut. Your dividend payment might also be partly a return of your own original capital, in which case you’re not earning as much as you think.

Not that you can always tell what’s going on with FFO. Some REITs fudge that number or structure themselves to benefit their sponsors more than their shareholders.

Mortgage REITs haven’t as good a performance history as equity REITs. Instead of buying properties, they invest in mortgages (bad in 2008–2009) and, sometimes, construction loans. They may have some sort of equity participation, so they’re not necessarily straight income investments. Still, they behave more like bonds than stocks, doing their best when interest rates are stable. If you want to diversify into real estate, mortgage REITs don’t cut it.

Hybrid REITs combine equity and mortgage REITs. But for real estate participation, the equity side is the only one that counts.

REIT initial public offerings (IPOs)—companies selling stock for the first time—are always risky. Untested real estate companies will try to raise money for properties they haven’t even bought yet. Well-established companies are more promising, although, like other IPOs, they might come to market overpriced. Best bet: don’t chase a new REIT stock. See if its price settles back after a few months and consider it then.

But consider secondary offerings—new issues of stock from REITs that are public already. They’re generally raising money to purchase more property. Their history tells you something about their likely success.

REITs Often Suffer from Conflicts of Interest. A mortgage REIT that lends to its sponsor has its sponsor’s needs in mind, not yours. An equity REIT “advised” by a developer may be paying too high an advisory fee, lending money to the developer or buying his or her properties at too high a price. REITs that invest in nursing homes may be controlled by the homes’ operators. Look for these interlocking relationships in the REIT’s prospectus, proxy statement, and annual reports (get them all from your broker before investing). You want an independent REIT, preferably one whose management owns a significant portion of the stock. (That’s in the proxy statement too.) Owner-managers are investing with you, not against you.

The Best Way to Buy REITs. Don’t try to analyze these complex stocks. Instead let a smart mutual fund manager buy them for you. Cohen & Steers (www.cohenandsteers.com, 800-330-7348) offers the widest range of U.S. funds, global funds, and exchange-traded funds; its expenses are high, however, and you pay up-front sales charges. No-load Fidelity has both a U.S. and an international REIT (www.fidelity.com, 800-343-3548). No-load Charles Schwab has a global REIT, covering both U.S. and international real estate companies (www.schwab.com, 866-893-6699). Vanguard’s REIT Index Fund is the low-cost choice (www.vanguard.com, 877-662-7447). For a full listing of REITs, mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds, go to REIT.com at www.reit.com. Check the expense ratio on any fund you consider. When you’re investing for income, it’s especially important to choose a fund that has low costs. Also, choose funds with long records, not the newer ones. For diversification, pick one U.S. fund and one international fund or a single global fund.

Some investors buy second mortgages or deeds of trust from people who don’t want to hold them anymore. For example, take a home owner who sells a house and takes back a note for part of the down payment. The buyer-borrower promises to pay over the next three or five years. After a while, however, the home seller wishes that he or she had cash instead. Enter an investor, who buys the note at a discount from its face value. Assuming that the borrower pays on time, these notes can yield a high rate of return.

Personally, I rank mortgages as my 21st favorite investment—roughly between unsecured loans to horseplayers and Chinese railway bonds. Here’s what you face:

1. These borrowers aren’t first-rate risks. If they were, they’d have had enough cash for the down payment or enough credit at the bank. Don’t invest without running a credit check, to be sure that the borrower always pays all of his or her loans on time. Don’t invest if the borrower put little or no money down on the home.

2. If you hold a second mortgage and the first mortgage goes into default, you may be wiped out. In foreclosure, the house may sell for enough to cover the first mortgage but not yours too. As a safety cushion, don’t invest unless the house is worth at least 30 percent more than all the loans against it—and get your own appraisal to prove it.

3. If the first mortgage goes into default, the only way to save your investment may be to make the payments yourself for a while, in hopes that the house can be sold for enough to cover both loans. If the house has value and goes to foreclosure, you might buy it yourself, repay the first mortgage holder, and hope to resell at a profit. (Investors in second mortgages need fat cash reserves.)

4. If the mortgage you’re holding goes into default and you want to foreclose, it will trigger foreclosure on the first mortgage too. Out of the frying pan and into the fire.

5. A property that looks good now will lose a lot of value if the economy sours or a local plant shuts down. You limit these risks by buying notes with no more than two or three years to run.

6. The highest yields come from mortgages or deeds of trust on properties that would be tough to dispose of if the borrower didn’t pay: raw land, cooperative apartments, vacation lots, mobile homes. In these cases, don’t invest unless the property’s appraised value is at least 50 percent more than all the loans against it.

The mortgage business is full of brokers who try to match investors with sellers in return for a finder’s fee. A broker may assure you that he or she has checked out the deal thoroughly—which may be false. Either do all the checking yourself or invest with a well-established broker known for dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. Lawyers are especially suited for making mortgage investments because they’re not daunted by the idea (or price) of going to court. If a court fight would worry you, let me suggest a few peaceful Chinese railway bonds.

Investors buy real estate to make a buck. They study the market, see an advantage, and go for it. But it’s riskier than, say, a no-load stock-owning mutual fund. Real estate in general may do well, eventually. But if your particular property comes a cropper—because of an environmental hazard, a lawsuit, a difficult tenant, a change of zoning, a market collapse—your loss can be huge. You can’t easily trade out of it, the way you can a stock. That’s what makes REITs more attractive than, say, raw land.

The classic argument for owning property is diversification. Real estate prices may go up at a time when stocks are going down.

But if diversification is the only draw, the average investor needn’t bother. You may own your own home. You may also own a vacation home. Odds are that a substantial percentage of your net worth is tied up in these properties. Your next logical step would be stocks rather than another piece of property. What’s more, stocks have greatly outperformed real estate prices over time.

The lure of real estate, however, isn’t always logical. A devoted investor becomes obsessed by properties—tromping through them, judging them, reshaping them, haggling over them. They’re not like mutual funds that you can buy and forget. You have to give real estate your soul.