CHAPTER 4

Jesus in the Sources of the Canonical Gospels

I

n this chapter we will examine witnesses to Jesus in the hypothetical sources of the canonical Gospels. Most research into these sources has attempted to discern how the Gospel writers used them, a task that (among other things) makes clearer the Gospels’ special emphases. This kind of treatment is, in the terminology of the present book’s title, “inside” the New Testament. Thus, earlier treatments of Jesus outside the New Testament do not touch upon the Gospel sources. However, since about 1970, scholars have treated these sources as though they were “outside” the New Testament, that is, as independent sources for our knowledge of Jesus. They testify to the earliest forms of Christianity or, as some argue, “Jesus movements” that existed before or alongside early forms of Christianity.

Four Gospel sources will be examined here as extracanonical witnesses to Jesus. Mark’s possible sources—miracle collections, an apocalyptic discourse, and an early passion narrative among them—seem so disparate to modern researchers that we need not consider them here.

272

First, we will discuss the material peculiar to Luke known as the “L” source. Second is the material peculiar to Matthew, dubbed “M.” L has some narrative contents, but both L and M primarily contain teachings of Jesus. Then we will consider the special source of the Fourth Gospel, most commonly called the “signs source.” This source may have been an early, full gospel like the canonical Gospels, with teaching in a narrative framework that ends with Jesus’ death and resurrection. Finally, we will devote the bulk of this chapter to an examination of the “sayings source” of Matthew and Luke, which goes by the name “Q.” This hypothetical source is predominantly (but not exclusively) composed of teaching material. Not only is Q a more complex source than the others, but it has also been a major topic, almost a storm center, of contemporary Jesus research.

Our interest in these four sources will not focus on how the canonical Gospels use them. Our task will be instead to discern what these sources can tell us about the historical Jesus. In each section, we will introduce the proposed source and outline its history of research. We will then give the contents of the source in table form, because they are too lengthy to reproduce in full here. We will then weigh its validity as a source in conversation with recent research and examine its view of Jesus.

L: Jesus, the Powerful Teacher and Healer

The intriguing introduction to the Gospel of Luke reads:

Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who were eyewitnesses and servants of the word from the beginning, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth about the things you have been taught. (Luke 1:1-4)

What were these many written (“set down”) accounts that Luke is trying to improve upon? Did he use them in his writing? Scholars have found many aspects of this introduction fascinating, especially its genre.

273

It implicitly raises the issue of this section, a special source of Luke’s Gospel not shared by the other Gospel writers.

In the overwhelmingly accepted hypothesis of Synoptic Gospel origins, the “two-source hypothesis,” the writer of the Gospel of Luke (and Matthew) used two main sources. First is the Gospel of Mark, which comprises about one third of Luke. With only a few exceptions, Luke follows Mark’s order and takes over large portions of his material, both teachings and narrative.

274

The second source is Q, teaching material that forms about one fifth of Luke. Luke may also have used an oral or written collection of material peculiar to his Gospel, a source named “L.” The material peculiar to Luke forms a large portion of this Gospel, variously estimated between one-third and one-half. Most of it sets forth the teachings of Jesus and contains some of his most memorable parables: the good Samaritan, the prodigal son, and the rich man and Lazarus. It also contains memorable narratives: the repentance of Zacchaeus, the disagreement between Mary and Martha over true service to Jesus, and the grateful Samaritan leper. Research into the historical Jesus has found the distinctive contents of Luke, both teaching and narrative, to have a high degree of authenticity. Scholarship into L as a source of Luke goes back to the beginning of the twentieth century with Bernard Weiss and Paul Feine, who were among the first to make a thorough case for an L source.

275

Although researchers treated it from time to time through the twentieth century, it never became a major topic of investigation. The hypothesis of a “Proto-Luke” Gospel was attractive to some and often militated against L, and the rising study of Q tended to eclipse study into other Gospel sources. However, since about 1980, interest in L has significantly increased.

276

Researchers have easily discerned the outer circle of possible L material: everything in Luke without parallel in Mark or Q. A few researchers have argued that Luke himself wrote all this material, so that none of it reflects a source. I. Howard Marshall has given good reasons why this extreme view is untenable.

277

On the other end of the spectrum are those who see a close relationship between most or all of Luke’s special material (

Sondergut

, in recent German scholarship on L) and the source L (

Sonderquelle

)

.

278

Most researchers who posit an L source find a median position by subtracting from this larger body those passages thought to be written by the author of Luke. Material that may have originated from another source, such as the infancy narratives, passion narratives, or resurrection appearance narratives, is also often excluded. This is where uncertainty enters, because of all the canonical Gospel writers, Luke is the most skillful in his general literary ability and particularly in using his sources. He is no “cut-and-paste” author whose L source can easily be distinguished from his own work.

Recent scholarship has not reached a consensus on the existence of L. Some scholars deny that the special Lukan material derives from an L source. Helmut Koester, for example, emphasizes the large size and formal heterogeneity of the material, features thought to exclude the existence of a single source.

279

Udo Schnelle also concludes that Luke has no L source, because “there are linguistic differences within the special materials, and the whole bears the marks of Luke’s own editorial work.... [B]oth the disparity of the materials and the lack of an internal principle of order speak against the existence of an independent source for Luke’s special materials.”

280

Eduard Schweizer, on the other hand, argues that L did exist, because: (1) L has analogies to sections for which we have external control in Mark and Q; (2) Luke refers in his preface to “many” written predecessors; (3) shared linguistic materials are notable within the proposed source; (4) the source has unifying themes such as women, the poor, and divine grace; (5) L has changes in the order of some of its material in comparison with Mark, and agreements with Matthew against Mark; and (6) tensions in Luke point to different layers of tradition beyond the use of Mark and Q.

281

In current research into L, the most thorough and careful work is a dissertation by Kim Paffenroth published in 1997, The Story of Jesus

according

to L. Paffenroth isolates a coherent L source by eliminating material that the Gospel writer composed or edited. He then analyzes the vocabulary and style, the formal characteristics, and the content of this remaining material. He concludes that “the L material does seem to have enough dissimilarities from Lukan style, form and content to make it probable” that it forms an L source. Moreover, he concludes that it is a coherent, unified source. L has strong elements of orality, but was more likely than not a document.

282

It was written by Jewish-Christians in Palestine sometime between 40 and 60 C.E. Some questions remain about Paffenroth’s efforts,

283

but he has offered the strongest case to date for an L source. I have chosen to draw upon his research here, because it is fairly indicative of the results of others who discern an L source, and because it is likely to form the basis for subsequent research into L.

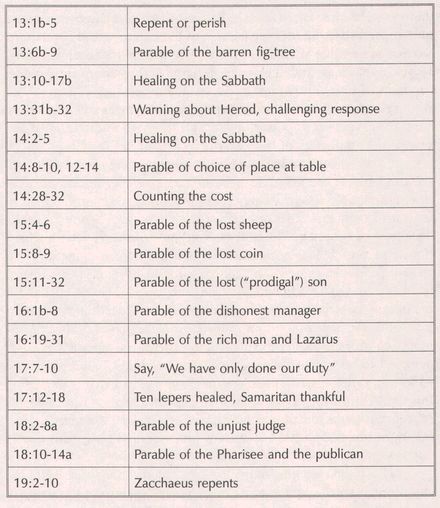

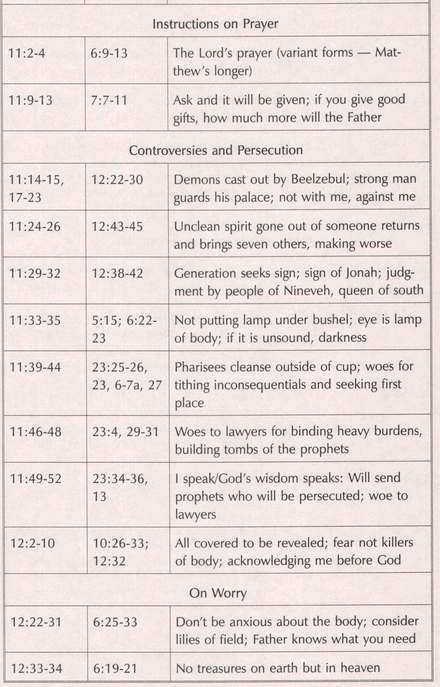

The contents of L that Paffenroth delimits are as follows:

284

Chart 1

The Contents of L in Luke

Assuming these contents are roughly indicative of the L source, how does it view Jesus? First, Jesus is an authoritative teacher of God’s radical, free grace. God’s grace forgives sin, heals human brokenness, and brings fallen members of God’s people back into the fold. Jesus is himself the agent of this activity. He came to “seek and find” the lost and to restore them to the covenantal people of God. This grace is first directed to Israel, but the bounds of Israel proper are broken, and the message of Jesus begins to go out into the world, when Samaritans are brought into the fold (implied at 10:30-37, 17:12-18). Jesus also acts to bring women into a freer state in God’s kingdom. The teachings of Jesus on wealth in L are, at least in Paffenroth’s reconstruction, remarkably conservative. Besides the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, Jesus stresses neither the virtues of poverty nor the dangers of wealth; these emphases are added by Luke, deriving perhaps from Q. Nor does the Jesus of L urge itinerant, impoverished missionary activity on his disciples; rather, a settled community of some means is implied. In sum, L sees Jesus as a “powerful ethical teacher who substantiated and revealed the authority of his teaching by acts of healing.”

285

It is also worth noting what is not present in the L source in comparison with the canonical Gospels. First, there are no christological titles in the source. Its christology is implicit in Jesus’ actions and teachings, with explicit touches of Elijah at its start in 4:25-27 and 7:11b-15. This type of prophetic christology is in line with early Jewish Christianity. Second, L does not present Jesus as a suffering, dying savior; it lacks a passion narrative, and its contents do not stress this role. It would be a mistake to conclude from this silence, however, that the community which used L did not know of Jesus’ death and resurrection, or thought them unimportant. This silence on the death and resurrection of Jesus could be explained in other ways, especially if L was designed to be only a collection of Jesus’ teachings to supplement a wider story of Jesus. Mark, Luke’s main source, had rich materials on this topic from which Luke drew, materials that perhaps displaced any reference to Jesus’ death that may have been in L.

286

Moreover, L does mention strong opposition to Jesus by Pharisees and potentially deadly opposition by Herod.

Is L a complete

telling of the message and meaning of Jesus for the community which likely used it? The answer depends on the shape of the L that is reconstructed from the special content of Luke, and how its genre is characterized. In Paffenroth’s reconstruction, L begins with John the Baptizer and stops before the passion. He excludes from L the special Lukan material such as the infancy narratives (chaps. 1-2), the women at the cross who followed Jesus (23:49) and the accounts of Jesus’ appearances after his resurrection (24:12-49). Although his reconstruction of L is shorter than that of most other critics, Paffenroth’s title points in the direction of L’s completeness: “the story of Jesus according to L.” Yet he does not deal explicitly or at any length with the completeness of L, an issue that should remain open in future research.

The Special Material of Matthew: An M Source on Jesus?

Readers of the Gospel of Matthew are often impressed by the context and content of its Sermon on the Mount in chapters 5-7. Jesus has just started to gather his disciples (4:18-22) and to launch his public ministry (4:17, 23-25). Then, after only the briefest mention of the main theme of Jesus’ teaching, the kingdom of heaven (4:17, 23), Matthew puts before his readers a long, complicated “sermon” detailing Jesus’ message. This discourse contains some of the most notable and influential teachings of Jesus: the beatitudes, authoritative reinterpretation of the law of Moses, warnings against hypocrisy, calls to trust in God, the “Golden Rule,” and others. The teaching of Jesus in Matthew has helped to gain it the place as the leading Gospel in Christianity. For example, though Matthew and Luke share common material, almost invariably Christians everywhere know and use the Matthean form of the beatitudes, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Sermon on the Mount.

Much of the influence of the Gospel of Matthew is owed to the fact that it presents teachings of Jesus that are not found in other Gospels. Matthew usually follows Mark’s order and content of Jesus’ actions, both in his ministry and passion. (One exception is Matthew’s moving most of Mark’s miracle accounts into one section, chapters 8- 9, and shortening them greatly.) Because Matthew uses Mark so extensively to relate Jesus’ deeds, most of his special material is comprised of Jesus’ teachings. Not surprisingly, then, reconstructions of M, the hypothetical source of Matthew’s special material, deal almost exclusively with teaching materials.

Three main efforts have been made to isolate an M source.

287

The first was B. H. Streeter’s

The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins.

288

Streeter defined M as all teaching material peculiar to Matthew, including Q material different enough from Luke to postulate a different form of Q influenced by Matthew. Streeter isolated the following: discourse material from Matthew 5-7, 10, 18, and 23; two parables from Matthew 13; and short sections of miscellaneous material from chapters 12, 15, 16, and 19. This source is Jewish-Christian, but not from the first generation of Christianity; instead, it shows a reaction to the law-free gospel of the Pauline mission. Streeter placed it in Jerusalem and linked it with the viewpoint, if not the person, of James.

The second main source-critical investigation was undertaken by T. W. Manson, in his wider study of

The Teachings of Jesus.

289

Manson shared most of Streeter’s method, but proposed a more extensive and developed M that included (1) teachings from the Sermon on the Mount material in chapters 5-7; (2) mission teachings from chapter 10; (3) miscellaneous material from chapter 11; (4) parables from chapter 13; (5) further miscellaneous material from chapters 15 and 16; (6) teachings on life with fellow believers in chapter 18; (7) instruction on service and reward from chapters 19 and 20; (8) sayings about “refusers” from chapters 21 and 22; (9) sayings against the Pharisees from chapter 23; and (10) teaching on eschatology from chapters 24 and 25. According to Manson, M derived from a church that was organized as a “school” of interpretation and that had a profound love-hate relationship with the Pharisees and their traditions. He dated M between 65 and 70 C.E. and, like Streeter, located it in the Jewish community of Jerusalem.

The third main study, published in 1946, was that of G. D. Kilpatrick,

The Origins of the Gospel of St. Matthew.

290

Kilpatrick concluded that M was a written source. He used a method common to the previous two studies and organized his M material into four sections: discourse, missionary charge, a collection of parables, and polemic against Jewish religious leaders. Kilpatrick attached other materials from other contexts in Matthew to the discourse and parables sections, but he was unable to place within his four main blocks many miscellaneous “fragments” of M.

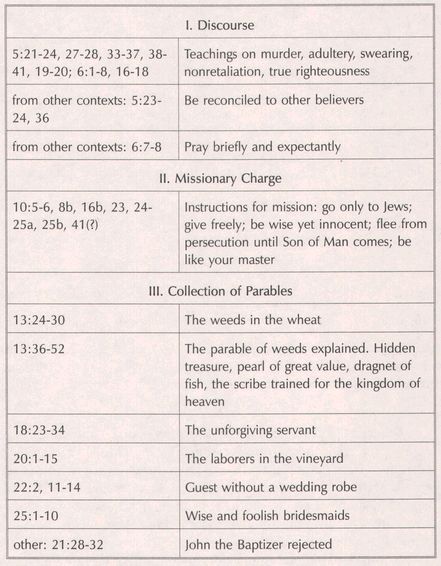

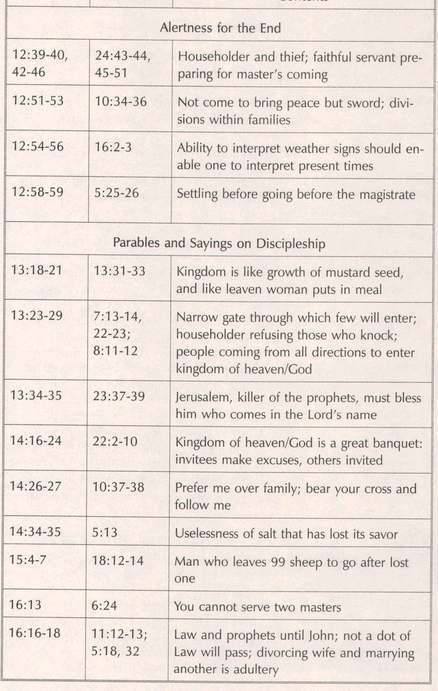

Since Kilpatrick’s is the most recent and comprehensive treatment of M, I will outline its contents here:

291

Chart 2

The Contents of M in Matthew

Kilpatrick argued that M was a written source containing only teaching material; the

narratives

peculiar to the Gospel of Matthew were added by the evangelist. Material from the M source supplied the bulk of Matthew’s special teaching content. Kilpatrick also concluded that the M source has a “weakness in connexion”: “because of the lack of any links, narrative or otherwise, it is impossible to see the plan or formal character of the source as a whole.”

292

The small size of M (170 verses), its lack of internal connection, and its lack of narrative all sug-gest that M was a “rudimentary document.” About the place, date, and authorship of M, Kilpatrick remained uncertain.

Although a single portrait of Jesus does not emerge from the M source, it does seem to roughly characterize him as an authoritative leader who founded the church, not just his apostolic band. Jesus sends his followers only to Jews. He reinterprets the law of Moses to fulfill its original intent, and the criterion of judgment by God at the end will be righteousness, the fulfillment of the law’s inner demand as interpreted by Jesus. The end of time presses near, and Jesus is its herald.

The three main efforts to isolate M come from the first half of the twentieth century, and no comparable study has been done since then.

293

Research into M probably has been stifled by the view that Matthew’s special material contains relatively little authentic teaching of Jesus when compared to Mark or Q. Manson put it most forcefully (and, in my opinion, regrettably) when he suggested that the contents of M should be treated cautiously because it has suffered “adulteration” from Judaism.

294

When New Testament scholars are engaged in quests for the historical Jesus and his authentic teaching, M and its contents are left behind.

However, scholarship is correct in concluding on other grounds that the special material of Matthew likely does not reflect a single source, whether written or oral or a combination of the two. The lack of consensus on the basic contents and structure of M stems from the considerable heterogeneity of the material unique to Matthew. This material simply varies too widely in style and content to reflect a single document, which we would expect to have some common literary style and religious message. This judgment is exemplified in Kilpatrick’s study, where approximately one-third of his M is either “other” material attached to the main sections, or miscellaneous, seemingly unrelated “fragments.” As Udo Schnelle argues, “The Matthean body of special materials is not a unified complex of tradition, is without discernable theological organizing motifs, and is hardly to be assigned to a single circle of tradition bearers.”

295

Moreover, as with Luke, it is difficult to distinguish between the source material and the evangelist’s own redaction. The theological orientation of much of M is very close, if not identical, to the religious outlook of the author of Matthew.

A careful study of the special sayings material of Matthew by Stephenson H. Brooks tends to bear out this conclusion for M as a whole.

296

Brooks isolates and reconstructs the shorter sayings of M and shows that M reflects the history of the Matthean community. He concludes that there was no single written source for M sayings, for the following reasons: (1) there are few discernible editorial connections in the collected M sayings; (2) the minor narrative touches in transitional sentences and phrases show little evidence of pre-Matthean origin; and (3) the style and vocabulary of the isolated M sayings material does not show the kind of unity typical of a written source.

297

So, while some material may have been written, most seems to have existed in oral tradition alone. Moreover, that the sayings material reflects a history of perhaps thirty to forty years indicates that it may not have come to Matthew from one source. Although Brooks does not develop this conclusion, it is reasonable to assume that if the short M sayings do not reflect a written source, the same is likely true for the larger body of special Matthean material. Thus, while some of the special material of Matthew may well have come to him from various sources, the evidence does not indicate that he used a single M source, written or oral, containing most of his special material. This material likely reflects the mid-to-late history of Matthew’s church rather than an earlier, independent source that came to the Gospel writer as L came to Luke. In sum, no single extracanonical source witnesses to the historical Jesus in Matthew’s special material.

The Signs Source of the Fourth Gospel: Jesus the Messiah

Perceptive readers of the Fourth Gospel note that it seems to have two endings. The first, John 20:30-31, speaks of the “signs” (sēmeia

) or miracles of Jesus, which the author has written to convince his readers that Jesus is the Messiah. The second, John 21:24-25, is modeled after the first. It asserts the truth of the Beloved Disciple’s testimony contained in the Fourth Gospel and states with eloquent hyperbole that the world could not contain the books that should be written about the things Jesus did. The first ending’s emphasis on signs and the accounts of the signs that form much of John 1-11 have suggested to some that the Fourth Gospel has embedded within it a “signs source” (Source = Quelle

in German; hence the conventional siglum SQ for Sēmeia Quelle

).

Source criticism of the Fourth Gospel began in the early twentieth century, commencing after source criticism of the Synoptic Gospels was well under way. Such notable scholars as Julius Wellhausen, Wilhelm Bousset, Maurice Goguel, Eduard Schweizer, Joachim Jeremias, and Rudolf Bultmann labored on the sources of John.

298

Bultmann’s source-critical analysis in his magisterial commentary on John (1941) was exhaustive, and for several decades it exhausted further creative work in this area.

299

Bultmann posited several sources, including an SQ and a separate passion source, and made complex rearrangements of John’s contents. Continually revised through twenty-one editions, this book’s source-critical position remained the touchstone of debate for thirty years, and is still significant.

300

From the Second World War until about 1970, a more limited scholarly effort contented itself with either embroidering or unraveling Bultmann’s work. No consensus formed about the sources of the Fourth Gospel, with one key exception. Most source-critics, and many commentators, agreed with Bultmann that some sort of SQ lies behind John.

301

Then, two fresh efforts reopened the question: Robert

Fortna’s The Gospel of Signs: A Reconstruction of the Narrative Source Underlying the Fourth Gospel

(1970) and Urban von Wahlde’s

The Earliest Version of John’s Gospel: Recovering the Gospel of Signs

(1989).

302

These two books will form the basis of our analysis here. We will describe and examine Fortna’s hypothesis as the leading and most influential recent contribution to source criticism of John, and then treat von Wahlde’s work more briefly.

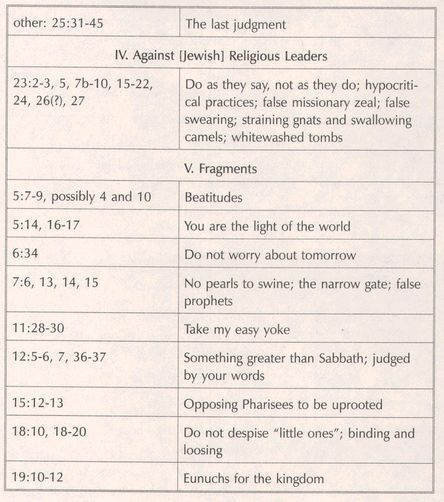

The contents of SQ as delimited by Fortna are as follows:

303

Table 3

The Contents of the Signs Source in John

Fortna gives a brief discussion of the character of SQ.

304

It was a written book, as its conclusion, now in John 20:30-31, makes explicit. A “gospel” in the same sense that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and even John are gospels, it presents a connected story of Jesus from the beginning of his ministry through his passion to its end in resurrection. All this is presented as a message to be believed, which its conclusion makes explicit. Because it has no developed teaching of Jesus, it is a “rudimentary gospel, but a gospel nevertheless.”

305

SQ is Jewish-Christian for reasons of Greek style and especially content. It has no concern with the Gentile question and no controversy about keeping the Law of Moses. Moreover, although Fortna does not make this explicit, its purpose indicates that the community that produced it was in active missionary contact with the wider Jewish community. Its social setting is hard to determine: “Whatever its roots, the Greek-speaking community which used the source as a gospel could have existed in almost any part of the Hellenistic world.”

306

Fortna cannot date SQ with any precision; it could have been written before or after the first Jewish revolt in 66-70 C.E.

According to Fortna, SQ was designed to function as a missionary book with the sole intent of showing that Jesus is the Messiah, presumably to potential Jewish converts.

307

Fortna explicates the theology of SQ as thoroughly christological. Jesus’ miracles are signs of his messianic status, and the passion account is “christologized” in SQ by the addition of sayings of Jesus that call attention to his messianic standing. SQ gives many titles to Jesus—Messiah/Christ, Son of God, Lamb of God, Lord, “King of the Jews”—but the first of these is central to all the rest. There is a consistent emphasis on the

fact

of Jesus’ messiahship to the complete exclusion of any explication of its nature. This would indicate that both SQ and the wider Jewish community it was missionizing had a common understanding of what messiahship entailed, an understanding that evidently centered around the notion that the Messiah would prove himself by miracles. SQ is indeed (to use Fortna’s characterization) “narrow” and “rudimentary” when compared to the canonical Gospels. Its narrowness may owe to its singular, strictly executed purpose: to convince its readers that Jesus is the Messiah in whom they should believe.

Urban von Wahlde’s source-critical work roughly confirms Fortna’s efforts. He seeks, as his title indicates, to recover “the earliest version” of John’s Gospel. This method entails first detecting the literary seams in the present Gospel. Then von Wahlde exploits four “linguistic differences” such as terms for religious authorities, miracles, and Judeans. Next he applies nine “ideological criteria” such as stereotyped formulas of belief, reaction of Pharisees to signs, division of opinion about Jesus, and especially “the predominance of narrative.” Theological criteria come next, including christology and soteriology. Finally, five miscellaneous criteria are employed. His analysis yields thirty-seven units covering almost all of Fortna’s source, and extending it by about one-third.

308

This signs gospel has more transitional sections than Fortna’s and features foreshadowing of Jesus’ death. Von Wahlde interprets the background and theology of the source in much the same way as Fortna. The signs call attention to Jesus’ power and engender belief in him, especially among the common people. The christology of the source is “low,” with a special background in Moses typology. The center of the signs gospel emphasizes that Jesus is Messiah. Von Wahlde places it in Judea because of the emphasis on Jesus’ ministry there. It was written perhaps from 70 to 80 C.E. in a Jewish-Christian community. On the whole, von Wahlde’s method is not as sophisticated or rigorously applied as Fortna’s, and the latter’s work continues to be the leading effort at discerning a signs source.

309

Raymond Brown has accurately stated, “In the last decades of the twentieth century one cannot speak of a unanimous approach to John:”

310

In particular, among those who do hold to a signs source, there is no strong consensus on what precisely was in it. The major point in this lack of consensus concerns whether SQ contained a passion and resurrection narrative. Is SQ unique among all precanonical sources in having such a narrative, or did it contain only the signs Jesus did during his ministry? Both Fortna and von Wahlde reconstruct full-blown signs gospels with passion and resurrection narratives, but many scholars disagree. Bultmann and others following him, for instance, have posited separate passion/resurrection sources.

311

Very little in the first half of Fortna’s SQ points to the death of Jesus, and very little in the second half points back to the first half. Moreover, with Fortna’s placement of the cleansing of the temple and death plot at the beginning of the passion narrative, the first half of his SQ shows no hostility against Jesus that would foreshadow his death. This lack of reference to Jesus’ death and resurrection would be odd indeed for the first half of a full gospel, even a rudimentary one. Then, too, the second half of his SQ features the formula “thus the scripture was fulfilled,” which the first half does not. This discrepancy seems implausible if SQ was a full gospel with passion and resurrection narratives. Why should a signs gospel insist that Jesus’ passion is the fulfillment of scripture but not use explicit scriptural argument to establish Jesus’ messiahship? Further, that the signs performed by Jesus total seven, the biblical number of fullness, may be an indication that the signs source dealt with only the public ministry of Jesus and not his passion and resurrection as well.

Q: Jesus, the Agent of the Kingdom of God

Readers of the Gospels have long noted that Matthew and Luke are remarkably similar to each other in their presentation of the teaching of Jesus, and that Mark lacks much of this teaching. Matthew and Luke have many more parables, “sermons,” and other sayings of Jesus than Mark does, and the material that Matthew and Luke share is very close in wording. From ancient times, this situation was explained by saying that Matthew was written first (Matthean priority) and that Mark and Luke used Matthew as a source, expanding or abridging it for their own needs. Today, most scholars maintain that Mark was written first (Markan priority) and that Matthew and Luke both drew upon two main sources: Mark and

≪

Q.≫

312

This theory of synoptic literary relationships is known as the “two-source hypothesis.

≫

Q can be defined simply but accurately as all the parallel material common to Matthew and Luke that is not found in Mark.

313

Of all the sources of the Gospels, Q is by far the most important in New Testament study. It has been continually researched for more than one hundred and fifty years, and since about 1970 has become a focal point, perhaps

the

focal point, of scholarship on the historical Jesus.

314

While the existence of M, L, and the Johannine signs source is not uniformly accepted, the Q hypothesis is embraced by an overwhelming majority of scholars. In this chapter we will briefly state the alternatives to the two-source hypothesis with its postulation of Q, outline the contents of Q, and describe recent study of it. Then we will focus on two questions important for our study: Does Q portray Jesus as a Jewish-Cynic teacher? What is the significance of the death and resurrection of Jesus for Q and its community? Our major concern in examining Q centers on its putative status as an independent, pre-Gospel source for the historical Jesus.

Did Q actually exist?

315

Once the priority of Mark is accepted, the common material in Matthew and Luke can be explained in one of two main ways: either one used the other, or they used a common source. That Matthew and Luke did not use each other is evident for several reasons. To begin with, as we noted above, both Matthew and Luke have a good deal of material peculiar to their Gospels. If either one used the other, we could reasonably expect much less special material. Then too, Matthew and Luke do not agree in order and wording against Mark. If one used the other, we would expect more agreement in the order and wording in Matthew and Luke when they differ from Mark. Also, the material common to Matthew and Luke but not in Mark is in a different order in Matthew and Luke, and often Luke’s form seems less developed. Matthew has the sayings material in five main blocks (Matthew 5—7, 10, 13, 18, 23—25), while Luke has it quite evenly dispersed (Luke 3-19). This difference in distribution is hard to explain if one used the other. Further, once the non-Markan material shared by Matthew and Luke is isolated, it seems to have a good deal of internal coherence in form and content, far more than L or M. Finally, the discovery of the

Gospel of Thomas

in 1945 silenced those who claimed that there was no analogy in early Christianity for a collection of Jesus sayings without a narrative framework. For these and some other reasons, the great majority of scholars have concluded that Matthew and Luke independently used a separate source for the common material they did not derive from Mark.

Although Q seems to be, in Michael Goulder’s term, a “juggernaut” in modern scholarship,

316

there are at least four other explanations for the similarities of Matthew and Luke against Mark that deny the existence of Q. The first is the “two-gospel hypothesis,” stoutly espoused by William R. Farmer and his associates.

317

It argues that Matthew was written first, that Luke then used Matthew as a main source, and that Mark abridged both of them. The second is the “multiple-stage hypothesis” of M.-E. Boismard.

318

This highly intricate theory postulates that four written sources of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Q formed the beginning of the Gospel tradition. Then two of these documents became what Boismard terms “Intermediate Mark” and “Intermediate Matthew.” Next, a Proto-Luke emerged with Q material and Intermediate Matthew material. Finally, parts of Intermediate Mark influenced the present forms of Matthew and Luke, and the present form of Mark uses Proto-Luke and Intermediate Matthew. The third hypothesis is from Michael Goulder, who has argued that Luke used the Gospel of Matthew and combined it with Mark.

319

Goulder views the special material of Luke as Lukan development of Matthew, and he argues that both the special material of Matthew and what others call Q are Matthew’s development of Mark. On his theory, Q is not necessary, so Goulder denies its existence. Goulder here expands the work of Austin Farrer.

320

Finally, Bo Reicke tried to explain the agreements among the Synoptics, including what others called Q, as parallels arising from oral tradition, not from written documents.

321

The Gospel writers had no contact with each other or with other written sources like Q.

These alternative theories are rightly rejected by most scholars as inadequate. Two (those of Farmer and Goulder) depend on Matthean priority. That Matthew was written first is of course possible

, but the theory of Matthean priority cannot adequately explain why Mark would use Matthew so oddly, expanding some of Matthew’s material so fully and at the same time radically cutting other parts, such as more than half of Jesus’ teaching in Matthew. Neither does the theory of Matthean priority explain why so much of Luke is special material; that this material represents Luke’s development of Matthew is simply not credible, given its different content and emphases. In addition, Boismard’s hypothesis impresses most scholars as unnecessarily complex, a violation of the scholarly principle that the simplest explanation is to be preferred. Most scholars rightly conclude about Reicke’s theory that the high degree of word-for-word similarity among the Synoptics cannot be explained by oral development alone of the Jesus tradition. As for Reicke’s corollary that the Gospel writers used no written sources, Luke 1:1-4 explicitly testifies that the author knew other sources, which makes it possible that he used them. The two-source hypothesis with its postulation of Q is therefore, despite some lingering problems, to be preferred to these four alternative hypotheses as the simplest and best

explanation of Synoptic origins and relationships. The case for Q is far stronger than any rival theory of Synoptic relationships. Q remains a hypothesis, and like every hypothesis it deserves to be tested constantly. However, it has been a fruitful working hypothesis and will likely remain so.

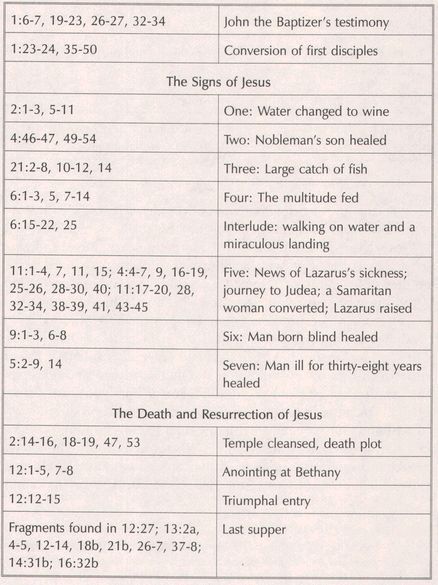

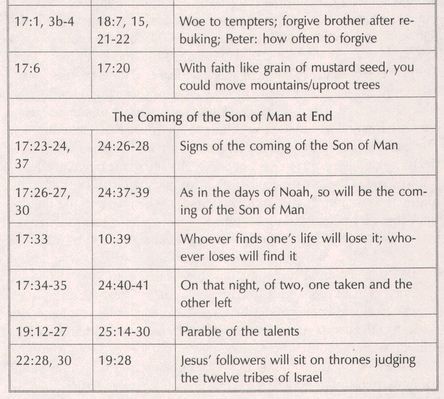

Research into the exact extent and wording of Q in Greek has been proceeding for more than a century now, and today is a special effort being led by the International Q Project, which reported annually from 1990 to 1997 in the Journal of Biblical Literature

and is now compiling a critical text of Q. While reconstructions of the exact contents of Q vary somewhat, the basic outline is clear. The following table outlines the commonly accepted general contents of Q.

Table 4

As this outline shows, Q contains mostly teachings of Jesus. It has only a few narratives, at the beginning with John the Baptizer and the temptations of Jesus, and near the middle with one miracle narrative (the Roman centurion’s servant). That Jesus worked many other miracles can be inferred from Luke 7:21, 10:13, and 11:20. In a few instances the teachings have a short narrative introduction or context (e.g., Luke 7:18-20, questions from the Baptizer). The teachings of Jesus are about equally divided between parables and shorter sayings. Wisdom sayings and eschatological sayings, many of them warnings, abound. The overall structure of Q shares a good deal with the later Synoptics. Like them, it begins with John and the temptations, and more treatment of John appears farther on. Q ends with, and the Synoptics have as their last main teaching section, a block of eschatological sayings and parables.

The precise sociohistorical setting of Q remains uncertain, but some consensus exists. Most researchers place it in Palestine, many in south-central Galilee, and a few in southern Syria. Q is a Jewish-Christian work and oriented to the people of Israel. The dates proposed for its writing vary from 40 to 70 C.E., with most in the middle of that range. The earlier part of the period may well have featured itinerant missionaries continuing the ministry and message of Jesus throughout the areas in which he worked. The initial collection of Jesus’ sayings that these itinerants used may have reached back to the first post-Easter community. These missionaries likely began the earliest settled Christian communities throughout the old territory of Israel. The end of the range, at 70 C.E., is the period of the Jewish revolt. Both missionary work and settled communities were probably severely disrupted by the war, and the predictions about Jerusalem and the temple do not seem to feature military action (Luke 13:34-35), as in the Synoptics. Also, the use of Q by Matthew and Luke, both commonly dated in the 80s, implies that Q would have been written and circulated some time before that decade.

Q was in all probability a written document. The high amount of verbal agreement between Matthew and Luke, especially in longer segments like the parables, is better explained by a written rather than oral source. At many points the passages are in parallel order in Matthew and Luke, which again points to a written source. Q was almost certainly written in Greek. Many Q traditions likely were at first in Aramaic, the language of Jesus and probably the early Palestinian itinerant missionaries. This, however, is not certain; the retroversion of Q texts into Aramaic is highly questionable and does not form an important subject in research into Q.

323

Since about 1970, in the most recent wave of interest in Q, much research has been devoted to discerning the compositional stages by which Q may have grown and to correlating the work’s growth with the history of the community that produced Q. This undertaking has been a most controversial element of Jesus research, and it is fraught with difficulties. Here we can only describe a few of the leading proposals and offer a brief critique. In perhaps the most influential reconstruc-tion of Q composition history, John Kloppenborg posits a three-stage model. Q1 was composed of “wisdom speeches” that promoted a radical countercultural lifestyle (e.g., the nucleus of the Sermon on the Plain/Mount, and Luke 11:2-4, 9-13, 12:2-12, 22-34). Q2 is the second stratum, with judgment against Israel when the wisdom message and its messengers encounter opposition (message of John the Baptizer, healing of centurion’s son, and the all apocalyptic material). Q3 was the last to be added, an exegetical stratum that moved Q closer to Torah-observant Judaism. The temptation story which presents Jesus as model for true relationship with God was also added at this stage.

324

Dieter Lührmann sees two main layers of material, the first having an eschatological one with sayings on the Son of Man, judgment, and the imminent parousia; and the second incorporating a mission to Gentiles and wisdom teachings, when the hope of an imminent parousia had waned. Lührmann sees the Q community as a Gentile Christian group that faced persecution from Jews.

325

Siegfried Schultz’s reconstruction posits two stages of Q and its community: an early Palestinian Jewish community with strong eschatological expectation and apocalyptic material in Q, and a later Hellenistic Jewish phase with other types of material.

326

M. Sato envisions three steps: “Redaction A” brought together material on John the Baptizer, “Redaction B” incorporated the material on mission, and “Redaction C” included declarations of judgment against Israel and wisdom teaching.

327

Given the diversity of its material, it is indeed likely that Q grew by stages. It probably began with the clustering of materials for preaching that were similar in both form and content. Then, as the mission to Israel continued, opposition and eventual failure led to the incorporation of other, diverse teaching materials stressing judgment on Israel and a turning to the Gentiles. What types of materials were added when is difficult to discern. Kloppenborg’s proposal that wisdom elements came first and apocalyptic elements second has been influential in North America, especially with Burton Mack, John Dominic Crossan, and other members of the Jesus Seminar, who argue that the historical Jesus was a wisdom teacher. But as the brief sketch above indicates, others have proposed that apocalyptic material was first and wisdom second. It is probably wrong to draw a firm distinction between sapiential and apocalyptic material and to force them into different strata of Q. Already in the history of Judaism, apocalypticism and wisdom had been powerfully blended in influential literature such as Daniel and

1 Enoch

.

328

There are some passages in Q that make it difficult to assign its wisdom and apocalyptic elements to different stages of composition. Adela Yarbro Collins, for example, has shown that eschatological “Son of Man” sayings occur in every layer of

Q

as stratified by recent research, and her conclusions on eschatology in Q have recently been ratified by Helmut Koester.

329

The same is true of other passages. In Luke 11:31-32, the Queen of the South, who “came from the ends of the earth to listen to the wisdom of Solomon,” will be a witness with the people of Nineveh at the judgment. In Luke 11:49 prophets and apostles are sent out by “the wisdom of God”; they will be persecuted “so that this generation may be charged with the blood of all the prophets” from the beginning. In Luke 12:4-7 steadfastness in the face of persecution is given first an eschatological basis (w. 4-5, fear God who can kill and then cast into hell) and then a wisdom basis (w. 6-7, God cares for sparrows, and you are of more value than many sparrows, so do not fear). Texts like these suggest that wisdom and apocalyptic materials were likely present throughout Q at its various stages of growth.

The time and manner in which material entered Q is also disputed. Are the narrative elements early, or were they added later as Q was on its way to becoming a gospel before being incorporated into Matthew and Luke?

330

And was later material invented outright? Some researchers imply or state explicitly that the later strata of Q were

created

by the Q tradents and that only the first stratum has a claim to represent authentic teaching of Jesus. Here we must recall the maxim that “tradition history is not literary history.” It is possible that the changing situation of the Q community would have led them to appropriate different teachings of Jesus that were swimming in the sea of Q oral tradition on which the Q document floated and to incorporate those teachings into written Q.

Many researchers question whether we can even correlate a literary stratigraphy

of Q with a communal

history

of the group that evidently produced it. For many scholars, though, it remains valid to ask what kind of a community is reflected by Q as a whole. Much attention has been paid to itinerant preachers of Q, especially for their role in using and developing the Jesus tradition. Passages such as Luke 9:57- 10:12, 12:22-31, 33-34, 51-53 seem to reflect the lifestyle of preachers sent out to extend the ministry of Jesus. They have left their families and are homeless; they practice poverty and depend on the generosity of the people among whom they work for their sparse livelihood; and they wander from town to town preaching before the Son of Man comes at the end of the age. They live and proclaim Jesus’ message, “Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God” (Luke 6:20). The description of Jesus’ itinerant followers in Q does also seem to indicate that they work miracles. However, this occurs only once (Luke 10:9), which may account for the little mention of miracles in Q itself.

Alongside this itinerant way of life, however, Q presupposes settled communities of believers with a different lifestyle.

331

“Remain in the same house.... Do not move from house to house” (Luke 10:7), while spoken to itinerants, puts some value on settled life. In Jesus’ strict forbidding of divorce, marriage is upheld as God’s continuing will (Luke 16:18). The ability to provide generous, seemingly continuous material support to others (Luke 6:30) shows that not all members of the Q community have given away all their property. The continuing necessity to choose between God and wealth (Luke 16:13) also directly implies a community with enough wealth to be tempted by riches. Q parables in particular, while not directly teaching about possessions, show a more positive attitude to settled life of some means: God is like a householder (13:25-30); God gives a rich banquet (14:16); God is like a man who owns one hundred sheep yet cares for one (15:4-7); and God gives rich talents to his people expecting them to be multiplied (19:12-27).

This implicitly positive view of settled life and some wealth would be unthinkable for a community comprised of only impoverished itinerants who view possessions as evil. Spiritual laxity and hypocrisy have entered the community, since some people can call Jesus “Lord” and not do his words (Luke 6:46-49). This situation seems more reflective of settled believers than of wandering, Spirit-filled missionaries. The existence of both itinerant preachers and settled communities in the wider Q community makes sense: preachers win converts, and unless all converts join them in their mission, settled communities of believers will soon develop. In the Q community radical and traditional ways of life probably challenged and enriched each other, a scenario not unlike others known from the New Testament and later church history when traveling missionaries and settled churches had a creative but strained relationship.

332

What is Q’s portrait of Jesus? While it is obvious that Jesus is a teacher, he is more than that. Jesus in his teaching is

God’s agent of salvation,

bringing the kingdom of God near enough for people to respond to it. “If it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come near to you” (Luke 11:20). Jesus is presented at the opening of Q as “the fulfillment of the prophets and in his person and words the authoritative expression of the law.”

333

He is the Son of Man (Luke 8:19-22, 11:16-19) and the Son of the Father (Luke 11:25-27). He is the final envoy of the Wisdom of God (Luke 7:35). Strikingly, Q does not call Jesus Messiah, but its christology may affirm Jesus as Messiah in everything but name.

334

One’s response to Jesus’ person and teaching determines one’s relationship to God in this world and one’s place in God’s kingdom in the world to come (Luke 12:8-9). Neutrality to Jesus is impossible (Luke 11:23). The time of salvation has dawned in Jesus, and those who hear and obey him are blessed. Those who reject Jesus come under God’s judgment, and warnings to flee from final judgment by turning to God are plentiful in Q. Miracles accompany Jesus’ authoritative teaching. Although Q narrates only one miracle, it also states that healings were characteristic of Jesus’ entire ministry: “the blind see and the lame walk, lepers are made clean and the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news preached to them” (Luke 7:22). Jesus sends out his disciples to announce this offer of salvation and the nearness of God’s kingdom (Luke 10:5-6, 9, 11). They, perhaps by implication like Jesus, are “like sheep among wolves” and will suffer persecution from Jews who do not believe (Luke 10:3, 6:22-23). Nevertheless, they must pick up the cross and follow Jesus (14:27) and meet persecution with love. Jesus in his earthly life is identified with the exalted Jesus, who will return as the Son of Man.

Was Jesus a Jewish Cynic?

At the end of the fourth century, Gregory of Nazianzus, recently retired to a monastery from his post as patriarch of Constantinople, asked, “Who has not heard of the Sinopean dog?”

335

He was speaking of Diogenes, the founder of the Cynic school. His question was rhetorical, for every educated or semi-educated person in the Roman Empire had heard of Diogenes. He was held up as a model of intellectual and moral courage by some and villified as a threat to goodness and order by others. Recent studies in Q reflect a similar division over the religious identity of Jesus, a division epitomized in the question Was Jesus a Cynic? This question is now one of the most hotly debated issues in studies on the christology of Q.

336

What with the traditional separation between Judaism and radical Greek philosophical schools,

337

and with the current emphasis on seeing Jesus within Judaism, it might seem a strange thing to argue that Jesus was a Cynic or was significantly influenced by Cynicism. We should begin with an outline of Cynicism and the proposed parallels to Jesus.

The Cynics were a Greek philosophical school that formed from Stoicism in the fifth century B.C.E. Early Cynics advocated “self-sufficiency” (

autarkeia

), a life of moral virtue by simplicity of life, and they rejected ordinary conventions of speech and behavior as pretense. Compared to members of other philosophical schools, Cynics were typically short on theory but long on praxis. The ideal Cynic, following the pattern of Diogenes (ca. 400-ca. 325 B.C.E.), reduced wants to a bare minimum, wore only a cloak, carried only a staff and a small begging bag for food, left hair and beard untrimmed, and cultivated a “boldness in speech” (

parrēsia

) to denounce stupidity, conventionality, and immorality. Cynics practiced radical renunciation of material goods, seeking freedom from attachment to possessions. Most notably, they also displayed “shamelessness” (

adiaphoria

) by doing shocking, obscene things to shake people out of their complacency. For example, they would sometimes eat food and spit it out as they lectured and, especially at the end of their presentation, defecate or engage in sexual activity (with others or alone) in public. This behavior likely earned them the name “Cynic,” which means ‟doglike.” With their orientation to praxis, they articulated no general philosophical system, even of ethics. Where more systematic ideas about religion did arise among a few Cynics, they viewed the gods as human constructs and rejected cultic practices as inherited superstitions; alternatively, they promoted the true god of Nature (and of their “natural” lifestyle). Cynicism waxed and waned in the ancient world, and the degree to which it flourished in the first century is debated. But it lasted until at least the third century C.E., when Diogenes Laertius wrote his

Lives of the Philosophers.

338

From this description, some evident parallels to the Cynics arise in the description of Jesus given in Q. Jesus was an itinerant teacher who called on his followers to lead an itinerant lifestyle as well. They were to leave their families (Luke 14:26). In his teaching, Jesus often put things in a provocative way. He criticized those who had many possessions (Luke 7:24-26, 16:13). Instead, he urged a way of life based on simplicity and faith (Luke 12:22-24). Jesus stressed action over empty belief (Luke 6:46-49). His mission instructions to his disciples bear several similarities with Cynic practices (Luke 10). Those who argue that Jesus was a Jewish Cynic teacher often depend upon a stratification of Q that puts the wisdom material in the first, supposedly most authentic layer. They view Galilee—or parts of it, at least, such as the city of Sepphoris—as Hellenized enough to have Cynic teachers.

Dissimilarities to Cynicism are also evident in Q. In Luke 10, Jesus has authority over his disciples, which is most un-Cynic for people seeking radical autonomy. Jesus sends his disciples out two-by-two, suggestive of community (v. 1; “we” in v. 11; and the plural “you” that runs through w. 2-12), but Cynics in their view of self-sufficiency typically traveled solo. Jesus’ mission instructions are in some ways more radical than those of the Cynics: his followers are not to carry a bag or purse (v. 4). They are not to talk to anyone on the road, but only work in the towns (v. 11). They are dependent upon others for food and shelter (w. 7-8). The preaching of Jesus and his disciples is also different in key ways from Cynic teachings. For example, Dio writes, “Do you not see the animals and the birds, how much more free from sorrow and happier they are than human beings, how much healthier and stronger, how each of them lives as long as possible, although they have neither hands nor human intelligence. But to compensate for these and other limitations, they have the greatest blessing—they own no possessions” (Dio Chrysostom, Orations

10.16). In contrast, Jesus’ admonition about the birds is connected to faith: God feeds them, and God will feed you (Luke 12:22-31). Thus, Jesus’ ideas about ‟self-sufficiency” are quite different; instead, he teaches reliance on the sufficiency of God, a trait the humble poor of Israel embody. In sum, Q’s focus as a whole centers not on a lifestyle, but on Jesus himself. This personal connection between the master and disciple is lacking in Cynicism, but forms the essence of Jesus traditions in early Christianity.

The debate over these parallels continues, with each side claiming that the other misinterprets them. Obviously, some significant parallels exist, perhaps enough to say that Jesus was influenced, directly or indirectly, by Cynicism. But to our question “Was Jesus a Cynic?” the answer inclines strongly to the negative. That Q is a

sayings

tradition makes it difficult to deduce much from it about Jesus’

actions.

Because Cynics were known more by actions than teachings, it is difficult to identify the Jesus of Q as a Cynic with any certainty. The speech of Jesus in Q does not reflect the bawdiness common to Cynics, and the idea that some form of obscenity-free Cynicism was practiced in the first century has recently been rejected.

339

The mission instructions Jesus gave to his disciples in Q may have reflected his own practice, but this must remain an assumption. Further, the overall content of Jesus’ teaching is notably not Cynic. He teaches faith in the God of Judaism. His message has an eschatological background and meaning that cannot be shunted from any strata of

Q

. This eschatology, its meaning and urgency, undergirds Luke 10 and the life of the Q community. Finally, as we have seen, Q presupposes a settled community as well as itinerants, a setting that does not argue in favor of identifying Jesus as a Cynic. It is more fruitful to understand Jesus’ mission and message both in Q and other Jesus traditions on the model of an eschatological Jewish prophet.

No Concern for Cross and Resurrection?

What is the significance of the death and resurrection of Jesus for Q and its community? At first sight, this might seem to be a meaningless question, because Q does not have passion or resurrection narratives, or say anything explicit about these events. Most older interpreters of Q have argued that Q and its community presuppose some preaching of the cross and resurrection,

340

and this was formerly a consensus. Recently, however, some leading interpreters of Q have argued that because the death and resurrection of Jesus are not recorded in Q, the Q community did not know of these events or, if they did, did not think them important. For example, Stephen J. Patterson has written, “Together with the

Gospel of Thomas

, Q tells us that not all Christians chose Jesus’ death and resurrection as the focal point of their theological reflection.”

341

While John Kloppenborg acknowledges that “it would be absurd to suppose that those who framed Q were unaware of Jesus’ death,” they had a different understanding of his death drawn from wisdom traditions and the Deuteronomic history.

342

However, N. T. Wright urges, “It would be well to keep a tight rein on any theories which depend on the significance of, for instance, Q’s not having a passion narrative. Proceeding down that sort of road is like walking blindly into a maze without a map”

343

While it has been argued, most recently by Erik Franklin, that Q did have a passion narrative that is detectable in the similarities of Matthew’s and Luke’s passion narratives, this is a difficult thing to show evidence for, let alone prove.

344

The view that Q reflects an early form of the Jesus movement that did not care about the cross and resurrection is not sustainable. The eschatology of Q presumes Jesus’ death and resurrection. Despite the efforts of some scholars to eliminate all eschatology from the first layer(s) of Q, or to de-eschatologize terms like “the kingdom of God,” every stage of Q has a significant eschatological dimension. In particular, Q contains probable allusions to Jesus’ rejection, death, and return as Son of Man to judge the world. Prophets coming to Jerusalem, like Jesus, are always killed. Nevertheless, Jesus will triumph somehow over Jerusalem’s opposition and unbelief: “I tell you, you will not see me until the time comes when you say, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord’” (Luke 13:34-35). Jesus’ death is presupposed most prominently in the saying that his disciples must pick up their own cross and follow after him (Luke 14:27). This can hardly be explained as a metaphor for difficult discipleship with no reference to what actually happened to Jesus. The several sayings dealing with persecution of those who follow Jesus and preach his message may well have Jesus’ death in mind. Further, the Son of Man sayings identify Jesus with the Son of Man who will come at the end to judge. And even if one stratifies Q and assigns sayings about suffering to later stages, this shows that the Q community itself grew to understand that its collection of sayings had to be supplemented by some understanding of Jesus’ death. The basis for this is the strong association that Q makes between Jesus’ person and his teaching. So, although Q as we have it contains no passion and resurrection narratives, and probably never did, this lack should not be taken to mean that Q and its community downplayed or assigned no significance to the death and resurrection of Jesus, much less were ignorant of it. The evidence we have does not permit such a sweeping conclusion and may well point in the opposite direction.

Conclusions

The existence and value of the sources of the Gospels will likely remain lively topics of debate in New Testament research. L is accepted by some, with recent research leaning toward it. M remains unlikely as a single source for Matthew. John’s signs source is rather widely accepted, but its scope is disputed. Q is widely accepted as part of a solution to the Synoptic problem, but much controversy adheres to its origin, growth, and interpretation. Despite all the consensus that accompanies Q and to a much lesser degree L and the Johannine signs source, these sources remain hypothetical. No amount of consensus can constitute certainty in this regard, and the hypothetical nature of these sources can only be lifted by the discovery of actual documents or a reliable reference to them in other, as yet undiscovered documents, which is unlikely. Moreover, these documents may be incomplete. We know them only as the Gospels used them, and we do not know if they used them fully. Neither can we reconstruct their exact wording to a certainty, nor be sure of their exact internal order. The hypothetical nature of these reconstructed sources should always be kept in view. To take a small example, in my opinion Q passages should be cited as “Luke (chapter and verse)” or “Luke (chapter and verse) Q,” and not as “Q (chapter and verse).”

Scholarship should also welcome dissenting voices that challenge the existence of these sources, the way source-critics reconstruct them, and the use New Testament scholarship makes of them. Also, source critics should be duly cautious in their work.

345

Carefully applied, though, source-criticism of the Gospels is a necessary and often fruitful endeavor. Naysayers may reject it entirely as an inherently hypothetical enterprise, but then any theory designed to explain the Synoptic problem is hypothetical. Source criticism arises to a significant extent from the text itself and is an effort to solve its mysteries. Even radical proposals are welcomed as a part of the debate over Christian origins. As long as hypotheses are tested, and what is hypothetical is weighed against what is (more or less) known with greater certainty, the debate should move forward on the whole.

Research into L and the Johannine signs source is a still under-appreciated counterbalance to research on Q. As we have seen, L has just as much or more a claim to preserve authentic Jesus traditions as Q. With its narrative form, christological titles, and miracles, the Johannine signs source gives a needed counterpoint to Q. All too often, those who promote the value of Q tend to overlook other Gospel sources and imply that Q is representative of the

early Palestinian community. Only when a comprehensive view of the Gospels’ sources is taken will the relative contributions of all the sources become clear.

What happened to these no longer extant sources? It is obvious that, aside from being used in the Gospels, they disappeared without a trace. No manuscript evidence has survived, and no ancient Christian author mentions them. This silence in itself is not necessarily proof that they did not exist, as Michael Goulder claims.

346

The usual explanation offered is that when they were taken up by the Gospel writers, they became obsolete and were ‟lost.” This is very plausible, but the communities that used and copied them also disappeared, most likely into the churches that used the fuller Gospels.

Much is sometimes made of the distinction between the theologies of the sources and those of the Gospels in which they are preserved. But would the authors of Matthew, Mark, and Luke have used sources diametrically opposed to their own views? This is hardly plausible. We should assume at least

some

compatibility in theology between the Gospels and their sources. Matthew’s appropriation and adaptation of Q’s wisdom christology provides a prominent case in point.

347

The Gospel writers used their sources and combined them, sometime with other sources and always with their own compositional contributions. Q was set in a wider context, with a narrative framework for Jesus’ teaching taken largely from Mark and with a passion and resurrection narrative at the end. Luke incorporated as well his L source, bringing it in line with his overall religious ideas. The author of the Fourth Gospel used the signs source for much of the first half of his work, affirming and correcting its view of signs as he wrote.

348

Thus the authors of the canonical Gospels probably saw their sources as valid traditions about Jesus, but needing supplementation and correction. This may be part of what Luke means when he says that he has followed “everything” carefully from the first (Luke 1:3). In a way, the church continued this process by including four Gospels in the New Testament, so that it would continue to have four views; Gnostic Christians, to judge from Nag Hammadi, had even more diversity.

The picture of Jesus that emerges from these sources is varied. L presents Jesus as God’s authoritative teacher, whose miracles buttress his claim. The Johannine signs source presents him as God’s Messiah, belief in whom brings life. Q presents Jesus as God’s agent of the kingdom. The christology of these sources is “low” when compared to the full christologies of the Gospels, but this is to be expected. All the sources speak of the relationship between Jesus’ teaching and/or action and his person. They all claim that Jesus is God’s authoritative messenger and insist that one’s stance toward Jesus’ message and person determines one’s standing with God. In this sense, they are not representative of “Jesus movements,” but of Christianity. This view of Jesus is important when we think of how those who read these sources thought about the death and resurrection of Jesus. If only Jesus’ teaching is important in Q, if Jesus is not the “broker” of God’s rule, then his life, death, and resurrection are not important. But if his person and teaching connect, the door is open for these documents and their communities to join the developing full Gospels and their churches, who made such a connection.

Finally, should we reconstruct modern Christianity on the basis of precanonical sources? Should Q, for instance, be “admitted” to the New Testament canon? Robert Funk has urged just such a program. To a significant degree, this is a theological question, to which historical study can give only a partial answer. Given the nature of the Christian faith as historically based, however, the issue is important. The following four caveats should be considered. First, on which of the many interpretations of Q is Christianity to be based? Second, to “re-vision” Christianity on the basis of Q is to ignore other precanonical sources which also give an early view of Jesus. Third, to change Christianity on the basis of historical research alone

is to ignore the limitations of historical knowledge. If scholarship cannot discover for certain when and by whom the term “Q” arose in the nineteenth century, and what exactly it meant to those who first used it, how can scholarship reconstruct a first-century document Q to such a certainty that people will risk this life and the next on it? Fourth, in weighing the probability of any reconstruction of Christian origins, one should consider the increasing improbabilities of those that rest on multiple successive hypotheses. Probability theory states that the probability of a conclusion is found by multiplying the probabilities of each link in the chain leading to the conclusion. In this case, the conclusion that the earliest Q community represents the best model of Christianity rests successively on five assumptions: (1) Markan priority; (2) the existence of Q; (3) the reconstruction of the wording of Q; (4) the correct stratification of Q; (5) the comparative judgment that earliest Q is, compared to other early Christian literature, most representative of Jesus’ teaching. While most New Testament scholars accept (1) and (2), to press on all the way to (5) is to make this position exponentially more uncertain. This is not to argue that it cannot or should not be done; rather, it is to say that those who press on to (3), (4), and (5) should recognize the increasing tenuousness of their positions. The future of Q studies will in all probability be occupied with the issue of the ancient and modern significance of Q.