Three

THE EAST END

This 1868 rendering shows the quickening pace of development and infill and the increasing definition of neighborhoods. In an era before streetcars, the soon-to-be city organized itself on walking distances. Mill workers lived in duplexes on the east end, while supervisors and professionals built large homes on the west end. (Courtesy of Montgomery County Department of History and Archives.)

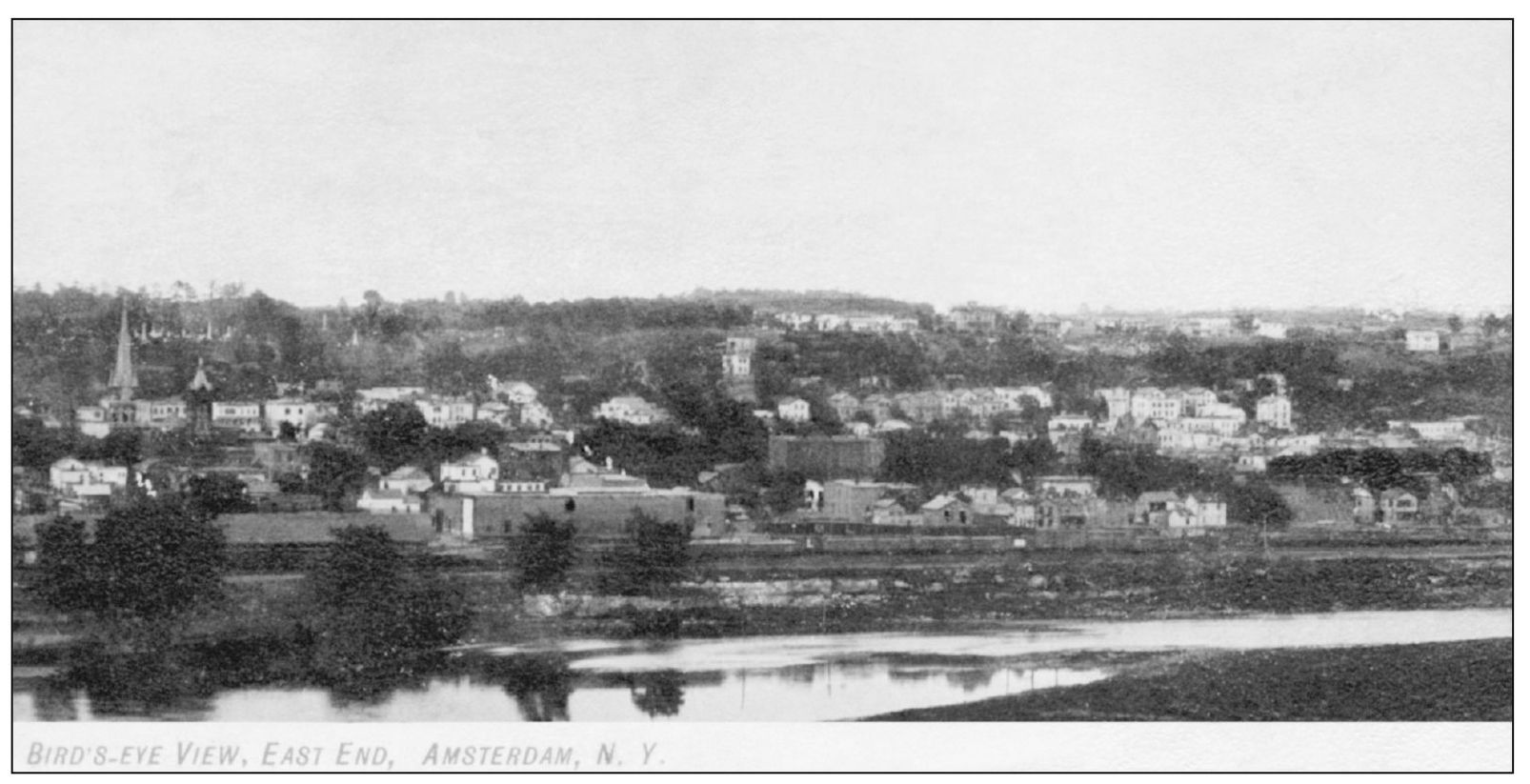

The east end is viewed here from the southwest; the distinctive steeple of St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church is visible on the left skyline. After the initial settlement in what became downtown, the next natural development of the village was along the flatlands to the east along the Mohawk Turnpike in the direction of the nearest city, Schenectady.

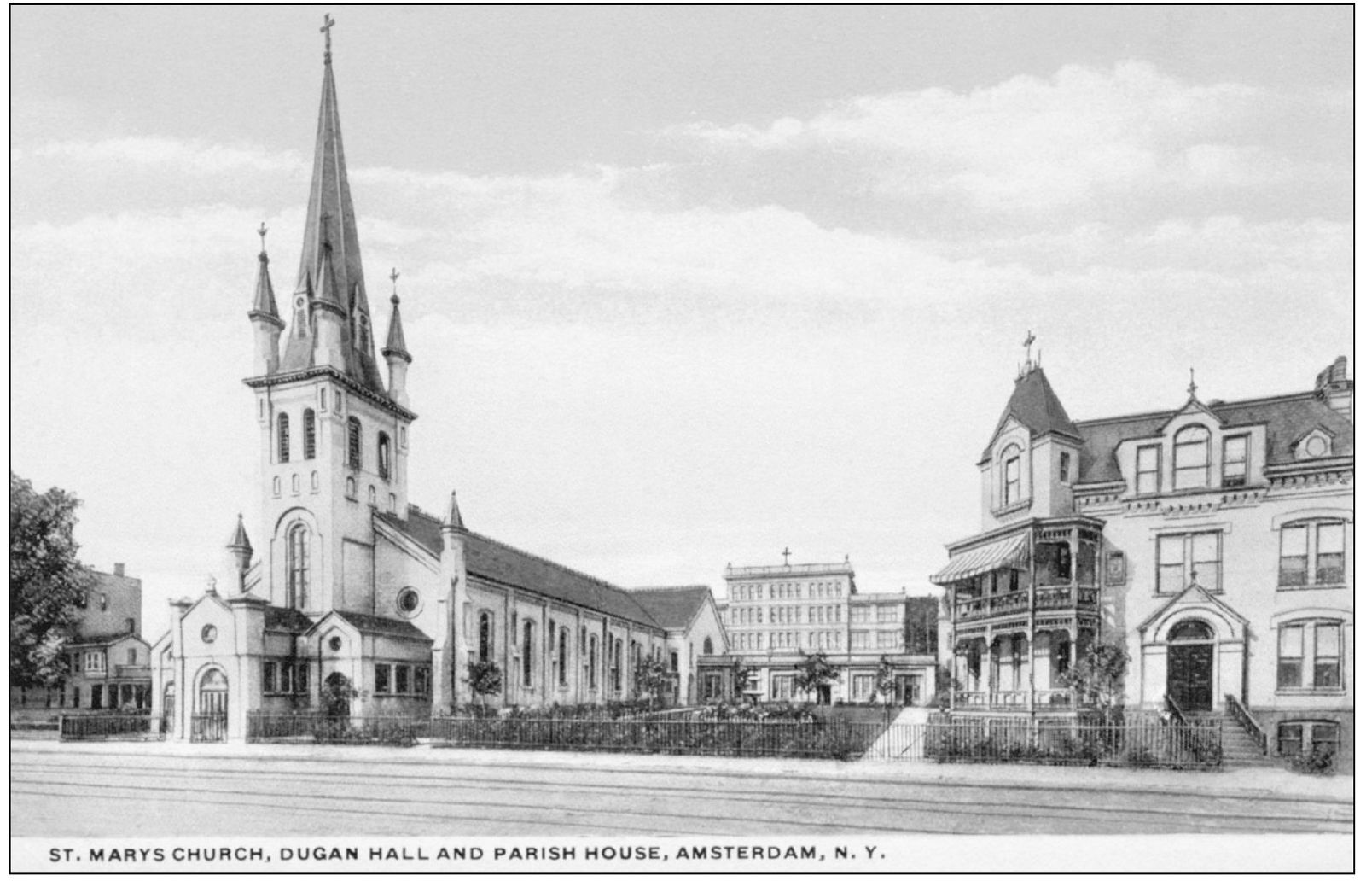

The parish of St. Mary’s was originally established on the south side of the Mohawk in 1839, where many of the city’s first Irish immigrants moved after building and working on the Erie Canal. As a new wave of Irish mill workers began to live on Reid (Cork) Hill in the east end, the decision was made to move the parish to the north side (1855) and erect a much more impressive church (1869).

One hallmark of the Catholic churches in Amsterdam has always been the devotion of their parishioners to the suitable appointment of their interiors. Some were more solemn, and others were more ornate, but all were impressive in their ability to convey the faith of their worshippers. In 2009, when budget concerns promoted closing two churches, laymen and clergy honored that tradition by working to see that much of the sacred art and objects found suitable futures.

From left to right are St. Mary’s Institute, the convent, and the rectory. Much of this property was lost to the arterial expansion of Route 5. Parish facilities are now housed in a modern structure immediately to the right (east) of the church. The original rectory was acquired in 1870 and damaged when the steeple blew down in 1873. The church itself has been expanded at least once and its exterior resurfaced.

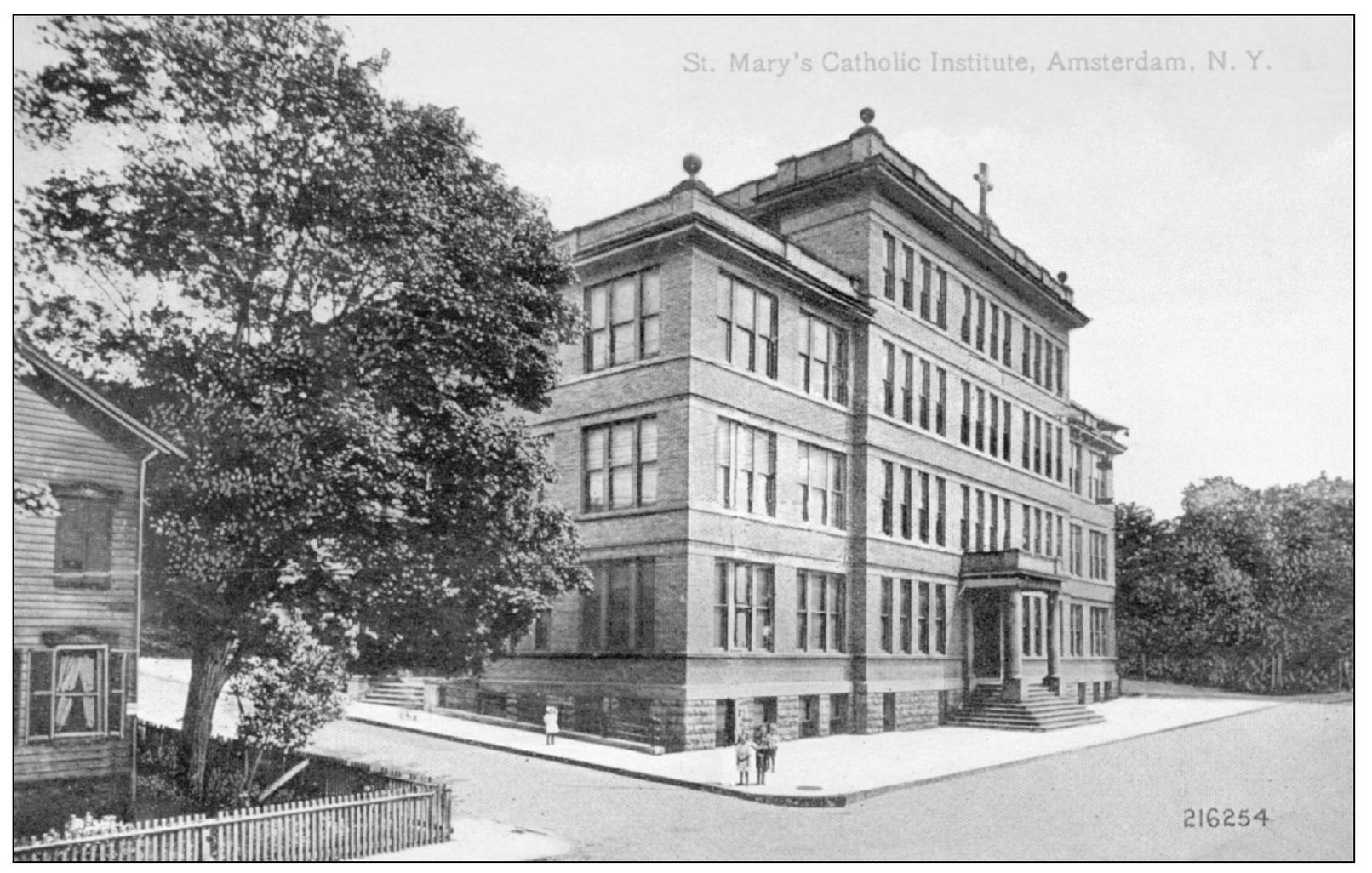

The original St. Mary’s Institute building sat much closer to Main Street. St. Mary’s was chartered in 1881 and was the first parochial school in Montgomery County. This building was replaced in 1909 by the structure seen in other images of the church grounds.

The front of the second St. Mary’s Institute faced Forbes Street. At left is a typical narrow clapboard balloon-on-frame home of the mid-1800s. At one time, these homes were seen as a sign of prosperity and improvement in the original village; by the last decades of the 1800s, they are increasingly viewed as relics to be replaced.

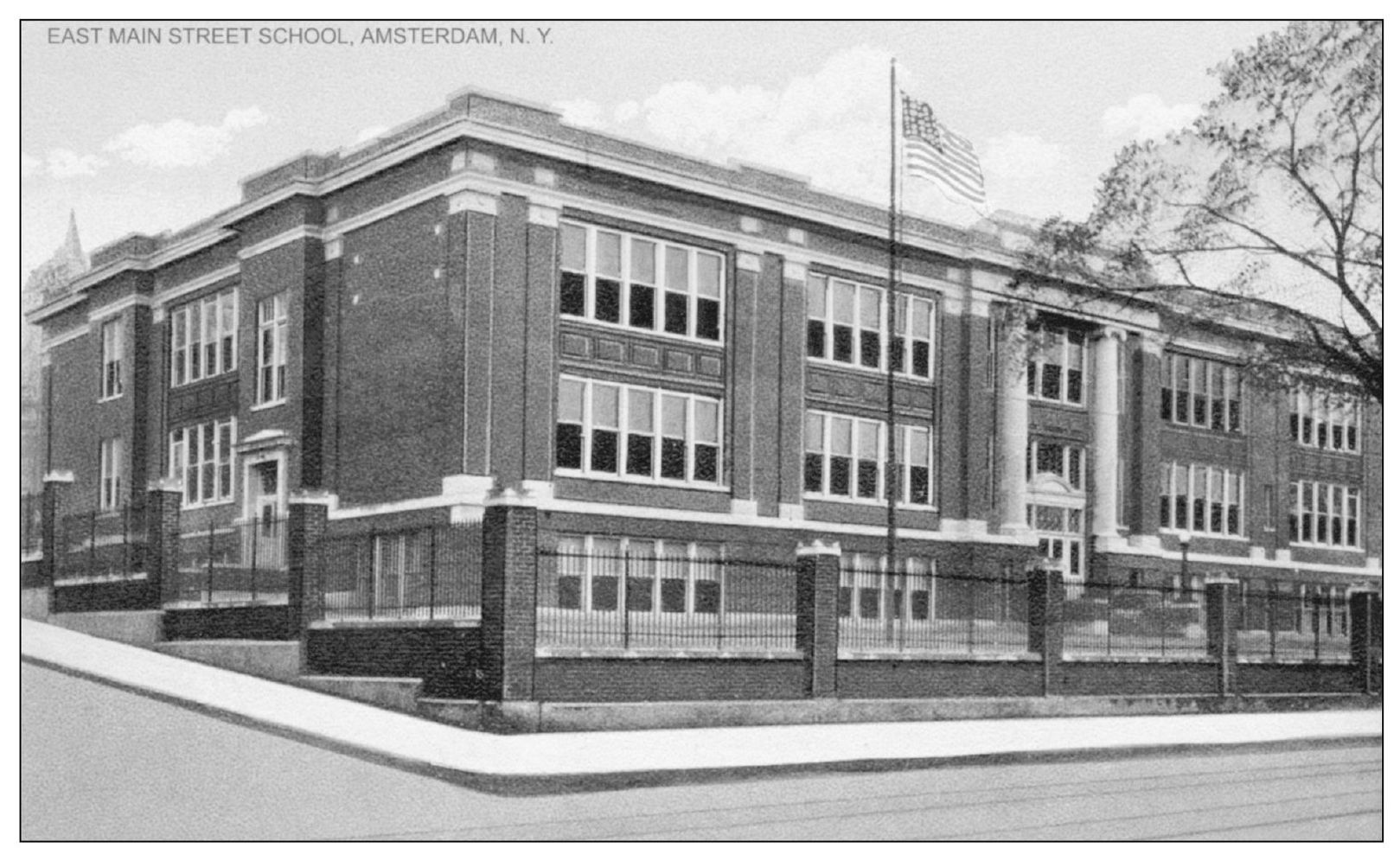

Here is East Main Street School, built in 1922. Later seen as excess by the school district, this became home to St. Mary’s Institute when its 1909 building fell to the construction of the Route 5 arterial highway prior to its eventual relocation to the north. Today it is the Calvary of God Church.

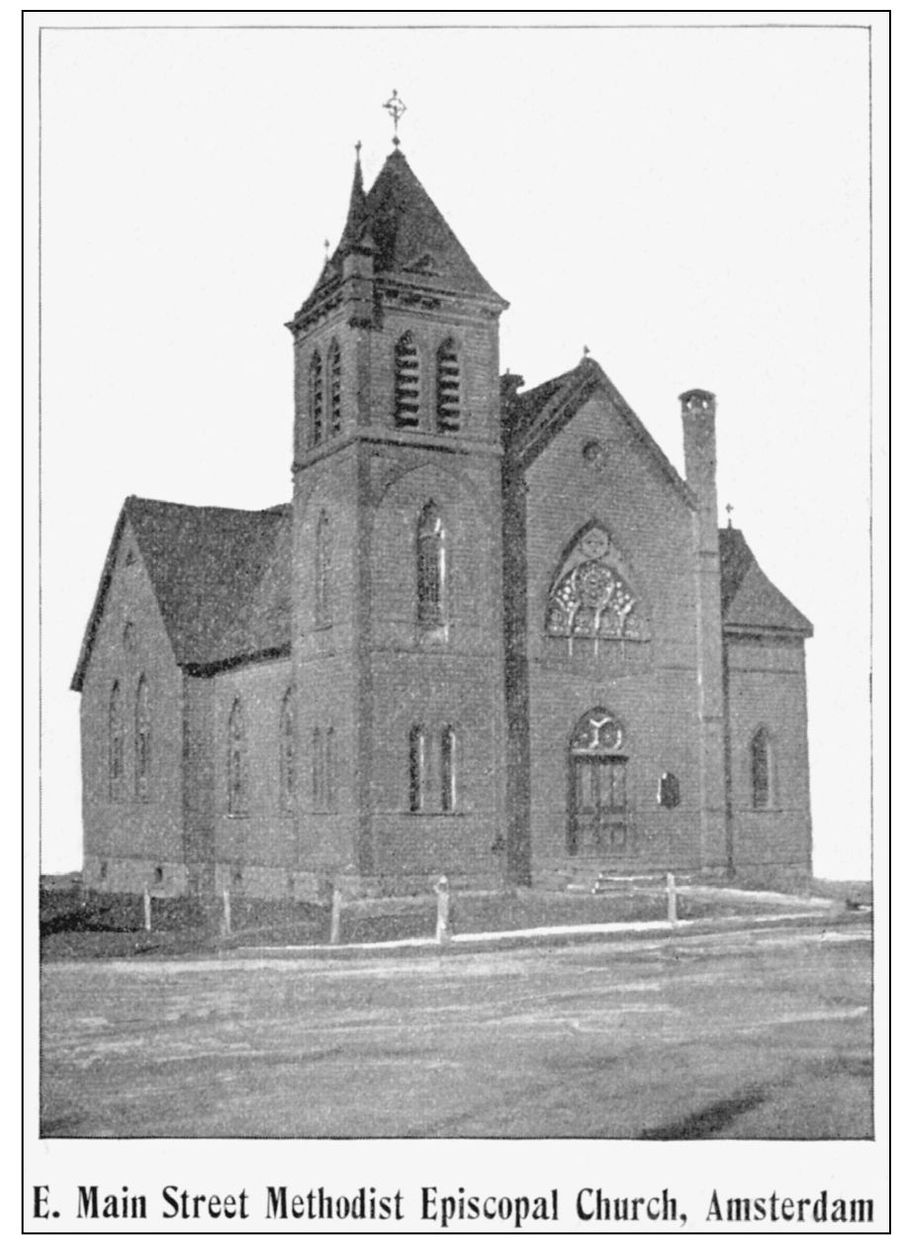

This church, located at the foot of Vrooman Avenue on East Main Street, was established in 1888. Its first members were mainly immigrants from Great Britain who came to work in the Shuttleworth Mills. The first Methodist classes were organized in the village in 1827, with a church organized by 1831.

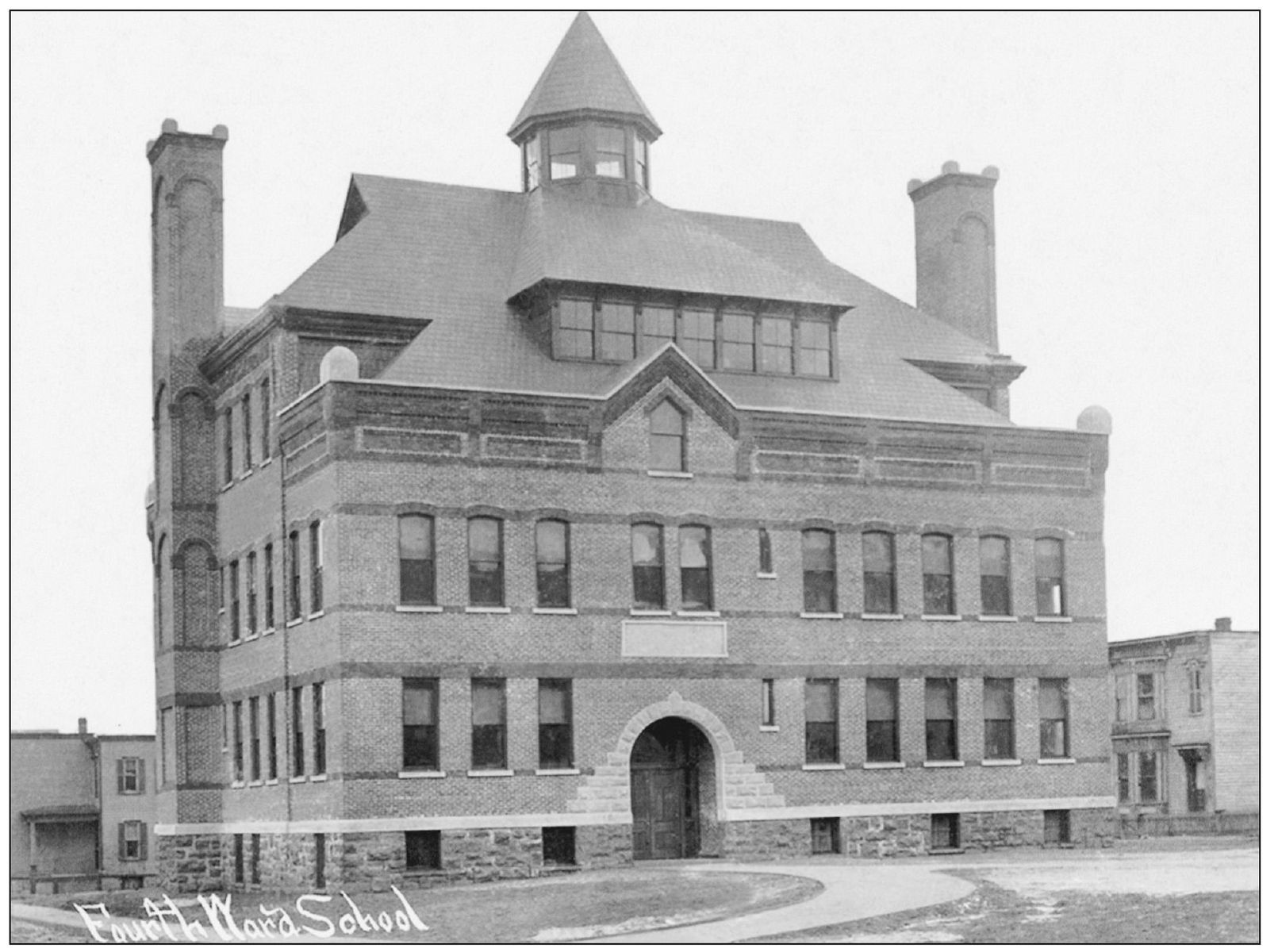

The Fourth Ward School was built on Vrooman Avenue south of Main Street in 1894. It was one of the last built in the city under the board of education constituted in 1855 prior to the consolidation of several school districts into the Amsterdam School District in 1895.

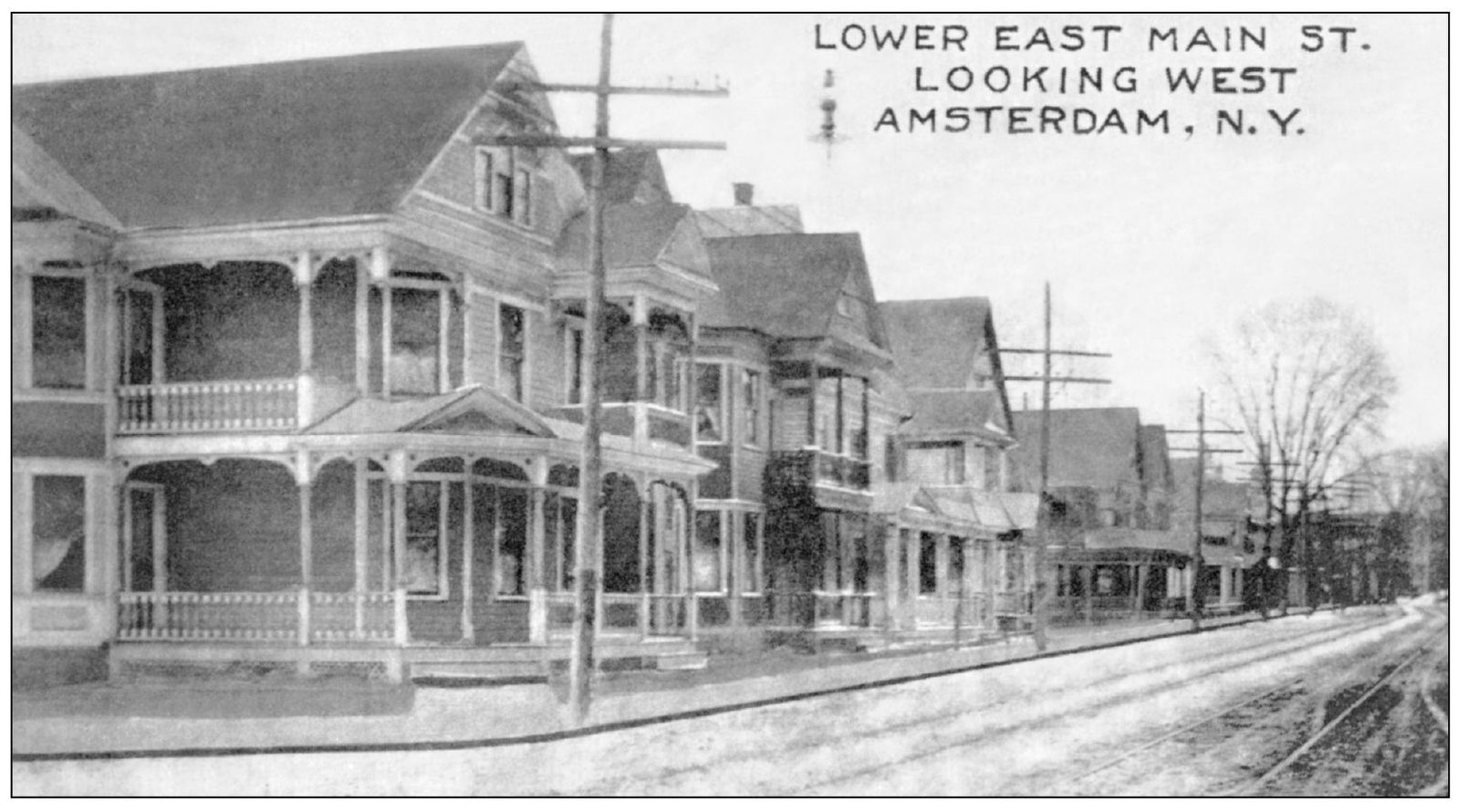

Many of these houses, minus their original ornamentation, still exist where Route 5 enters the city on the east and runs concurrent with a portion of East Main Street. Originally the homes of mill worker families, some were designed for single families, and others were two-family homes.

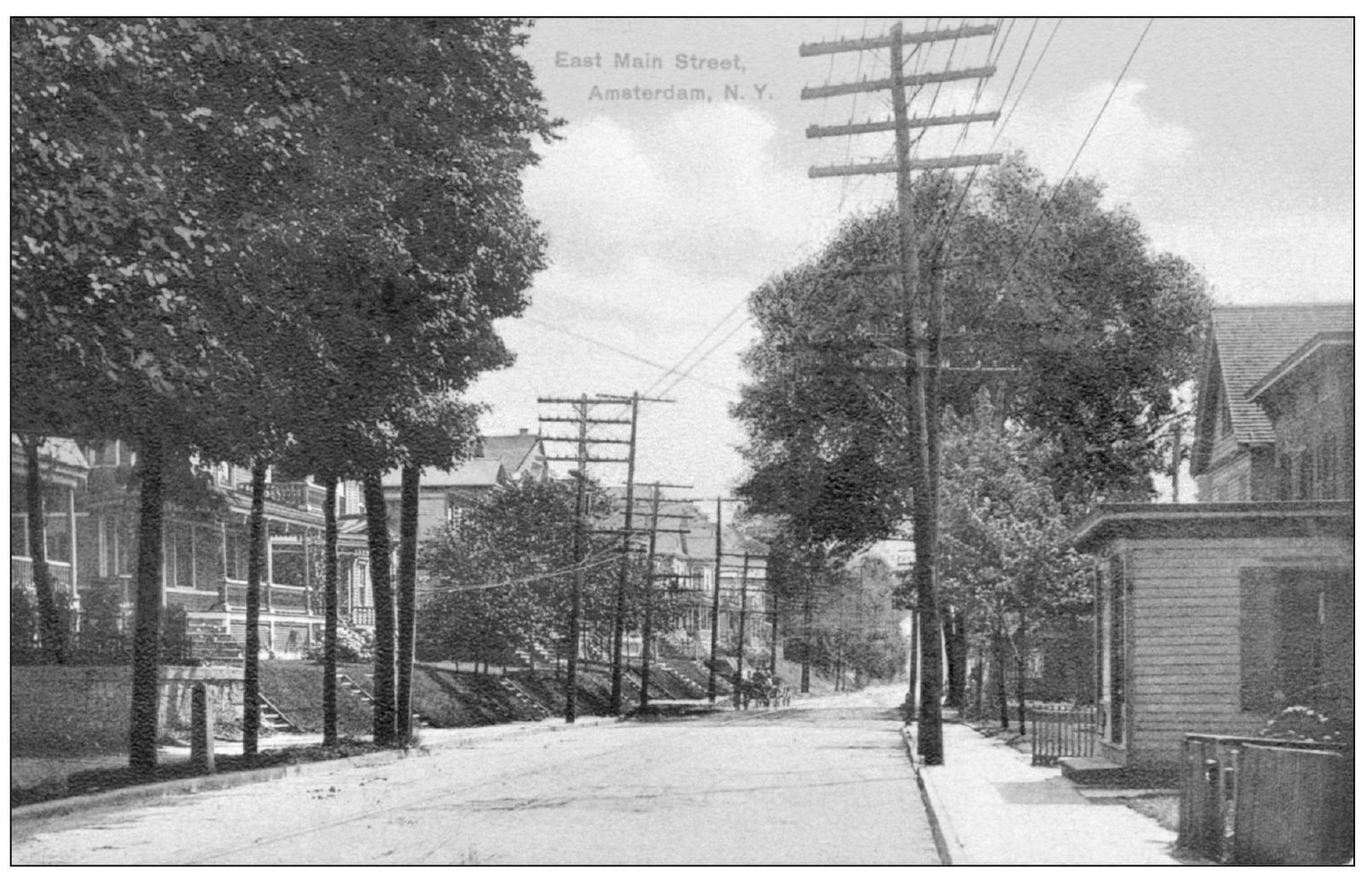

This is another view of Main Street in the east end looking east from Vrooman Avenue. The telephone poles have gone but so have many of the natural trees. Some fell victim to two waves of Dutch elm disease that swept through the city in the early decades of the 20th century. Others were removed in a misguided attempt to improve roadway safety.

Shortly after World War I, this park was renamed Coessens Park in honor of the first Amsterdamian killed in that conflict. Popular with city children for its pool and playground equipment, the park was encroached upon first by the construction of the city’s new Department of Public Works building to the west in the 1930s and later by the creation of an industrial park to the east.

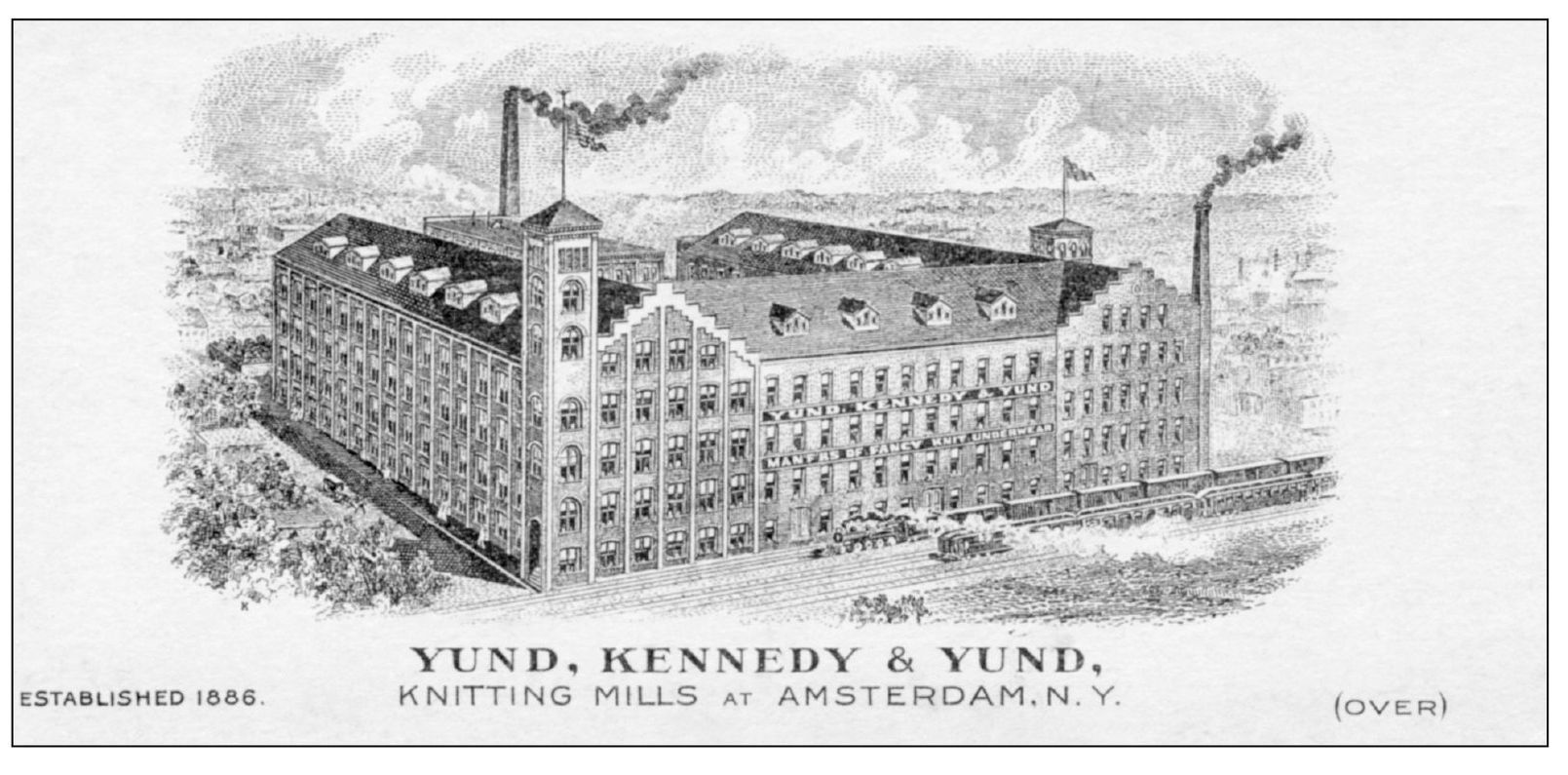

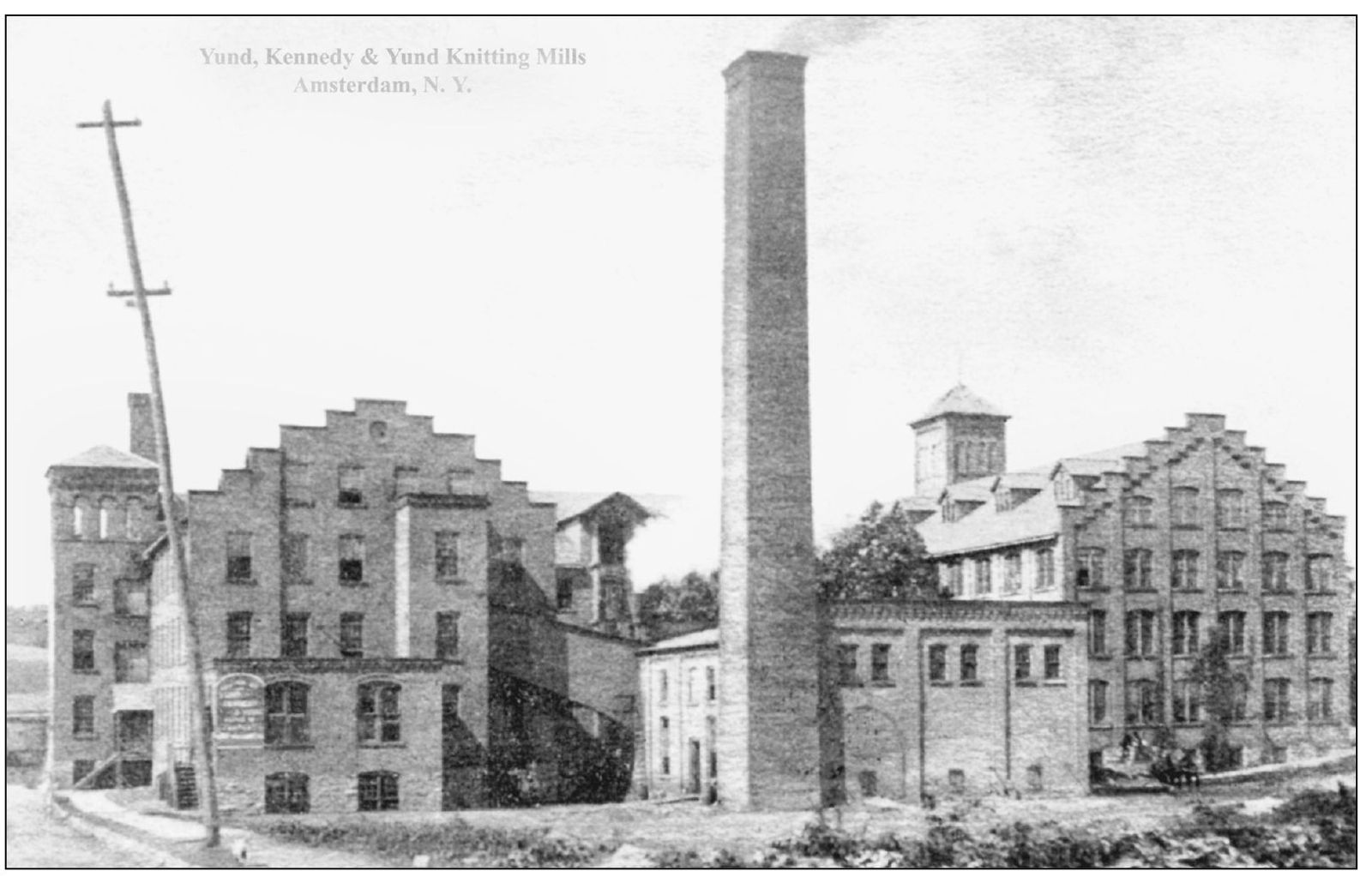

The Yund, Kennedy, and Yund Mills were established on Eagle Street in 1886 to produce knitted goods. Numerous other knitting mills were spread throughout the city, making it the second most prevalent business after carpet and rug making. Another major concern was broom making, which started early, using broom corn gown along the banks of the Mohawk River. Eventually there were at least seven firms in the city using corn stalks from the Midwest to manufacture almost all the corn floor and whisk brooms made in the United States.

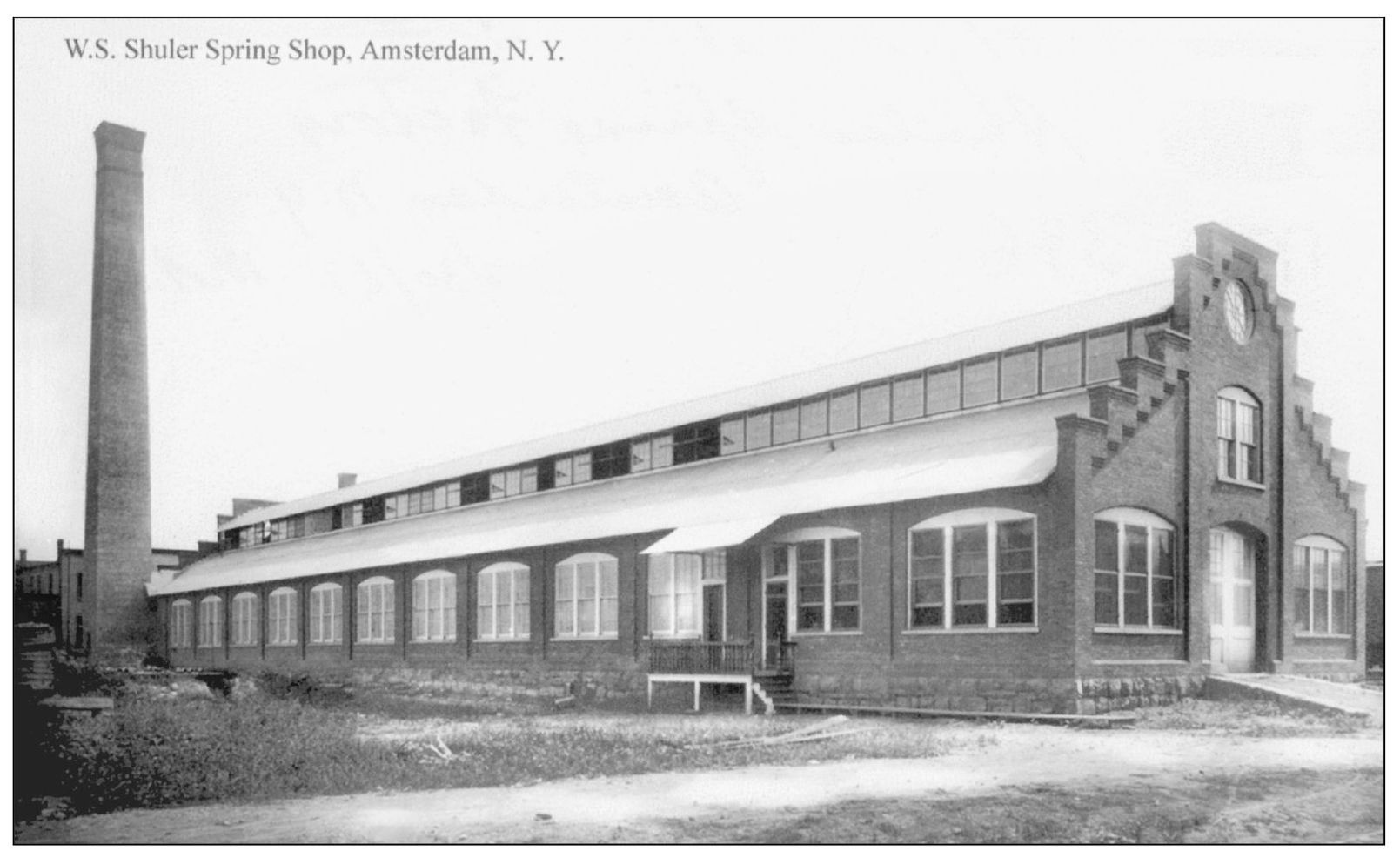

Sometime in the early 1900s, possibly due to a fire in 1903, the Shuler Spring manufacturing operation shifted from its original location on Church Street (see page 104) to this mill building on Eagle Street. The building was purchased and incorporated into the Shuttleworth holdings in 1920.

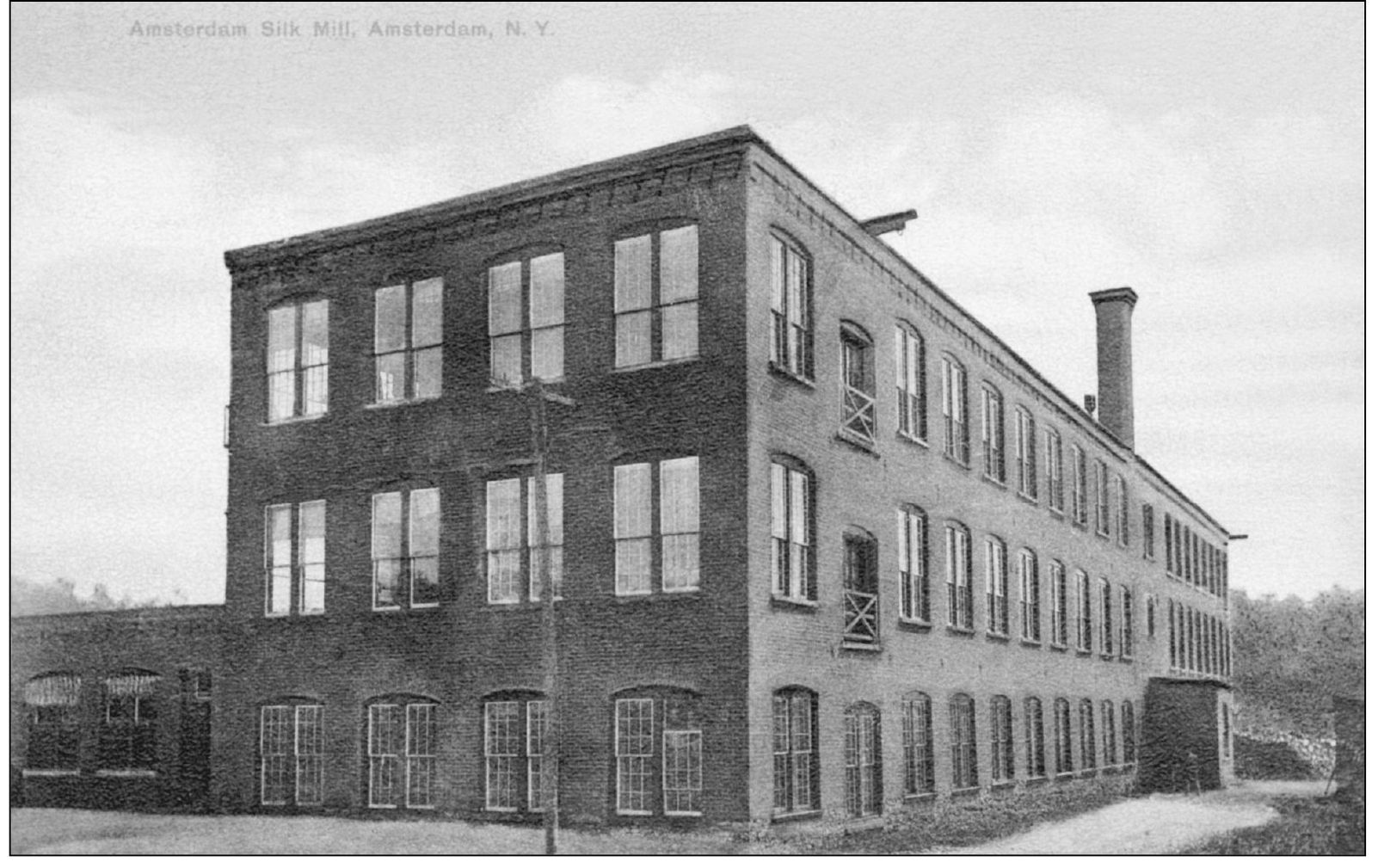

Established in 1889–1890, the Amsterdam Silk Mill manufactured gloves, hosiery, underwear, netting, and other silk products. It came under the control of Julius Kaiser and Company in 1903, part of a firm with plants in New York and Germany, and closed in 1924. In many ways, it was typical of the smaller mills and shops spread through the city that made products other than carpet, which were important to the Amsterdam economy.

This advertising card shows the McCleary, Wallin, and Crouse plant and the Shuttleworth plant, which were combined in 1920 to form Mohawk Mills. Locals for years afterwards referred to these as the upper mills and the lower mills, respectively. The first was located on the upper Chuctanunda Creek and the latter on the Mohawk River. The “From the looms of Mohawk” and other advertising campaigns gave Amsterdam and the Mohawk Valley their greatest modern national recognition.

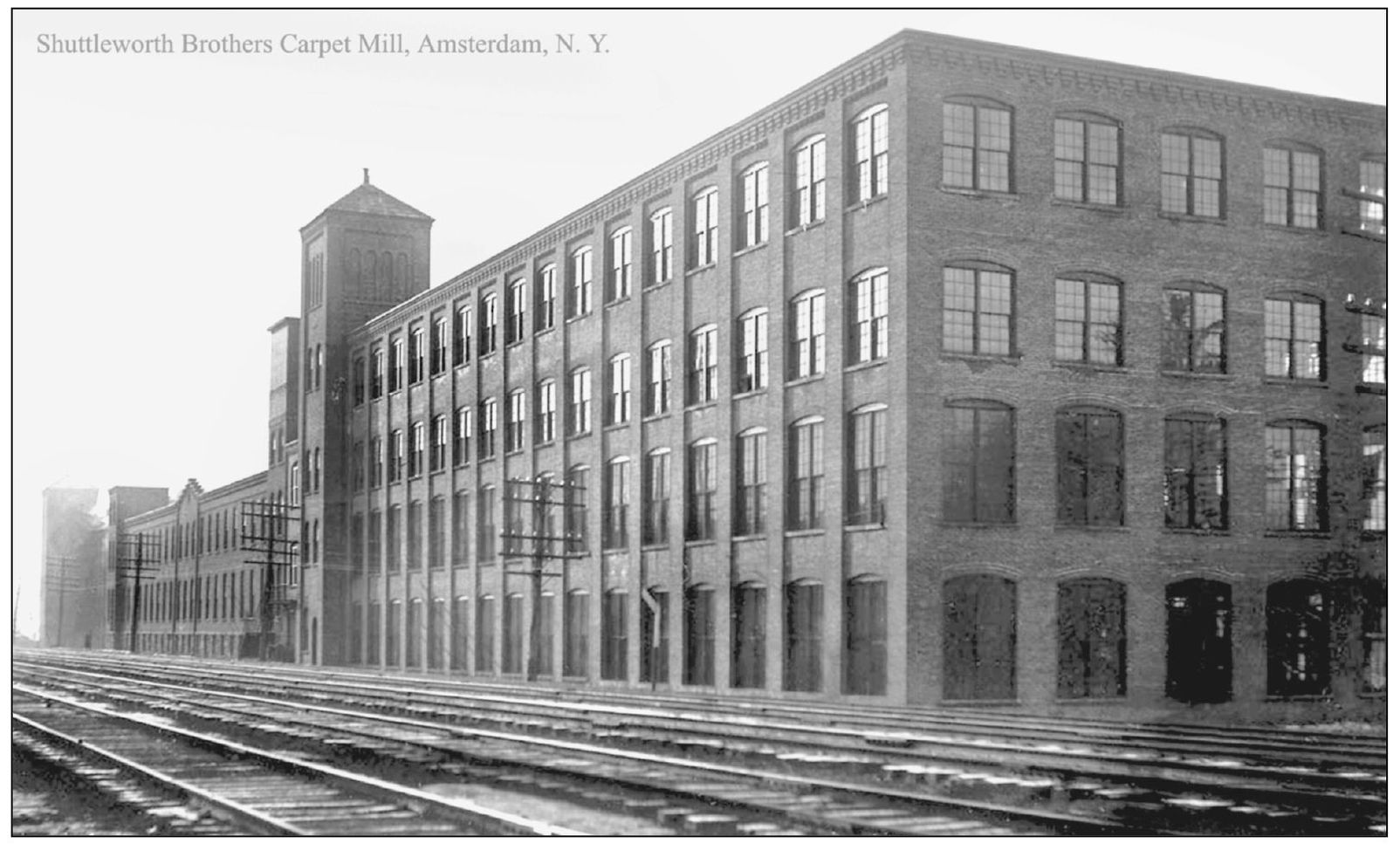

In 1872, the firm of Kline and Arnold attempted to give the Sanford Mills their first real competition but failed. Their original mill south of the New York Central Railroad tracks near the banks of the Mohawk River provided the basis for four aptly named brothers from England with carpet experience to establish their own company in 1878. In this view, the original Shuttleworth Mill is the three-story structure to the right.

Expansion was rapid during the first decade of operation, and additional buildings were constructed south of the train tracks. This view is similar to the previous but looks from east to west. As expansion continued north of the tracks, overhead connections were made over the train tracks to the more modern buildings on the north side.

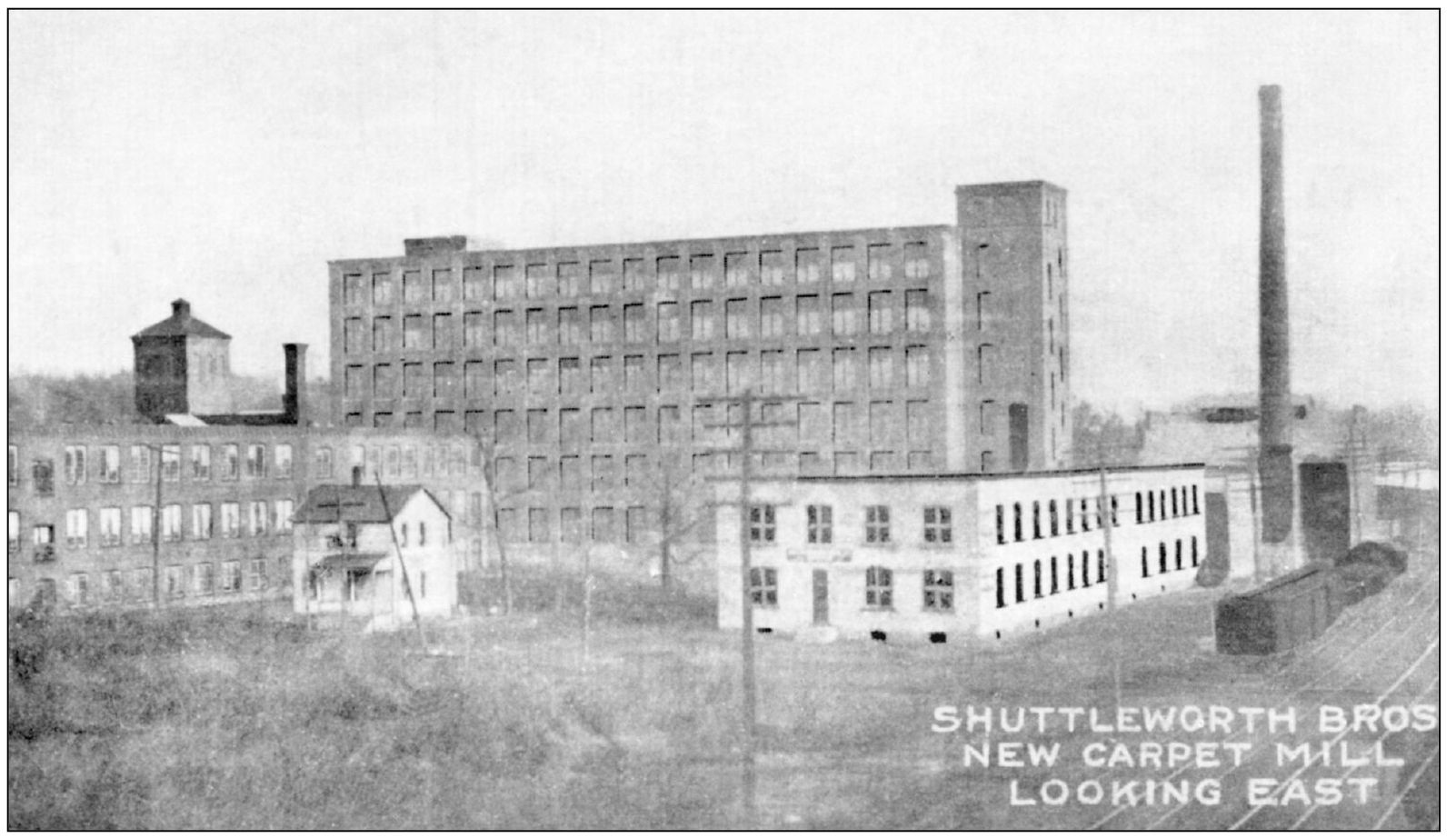

As business expanded so did the plants north of the rails. Operations in older buildings to the south were phased out, and a power plant was erected to reduce costs. Never having been dependant on waterpower permitted locating away from the Chuctanunda and closer to the New York Central Rail tracks. This allowed the firm to bring in coal and raw materials and ship product without reliance on the Amsterdam, Chuctanunda, and Northern Railroad. This view looks to the east, with the Amsterdam Silk Mill to the left.

The same buildings as the previous image are seen looking west, and the power plant’s coaling trestle and door are visible. Mohawk Mills survived the Depression and prospered in World War II, as did the Sanford Mills. In 1955, Mohawk merged with the Alexander Smith Company of Yonkers to become the ambiguous-sounding Mohasco (short for Mohawk Alexander Smith Company).

Herbert L. Shuttleworth II became president of the new firm. Shuttleworth regarded himself as an Amsterdamian and was noted for civic works, particularly with St. Mary’s Hospital, local baseball, and Shuttleworth Park. Corporate control remained in Amsterdam for a number of years. However, with over 17,000 employees worldwide and sales of $650 million annually, the pressure was soon on to move out of Amsterdam. All manufacturing operations ceased by 1968.