Seven

SPECIAL PLACES, SPECIAL TIMES

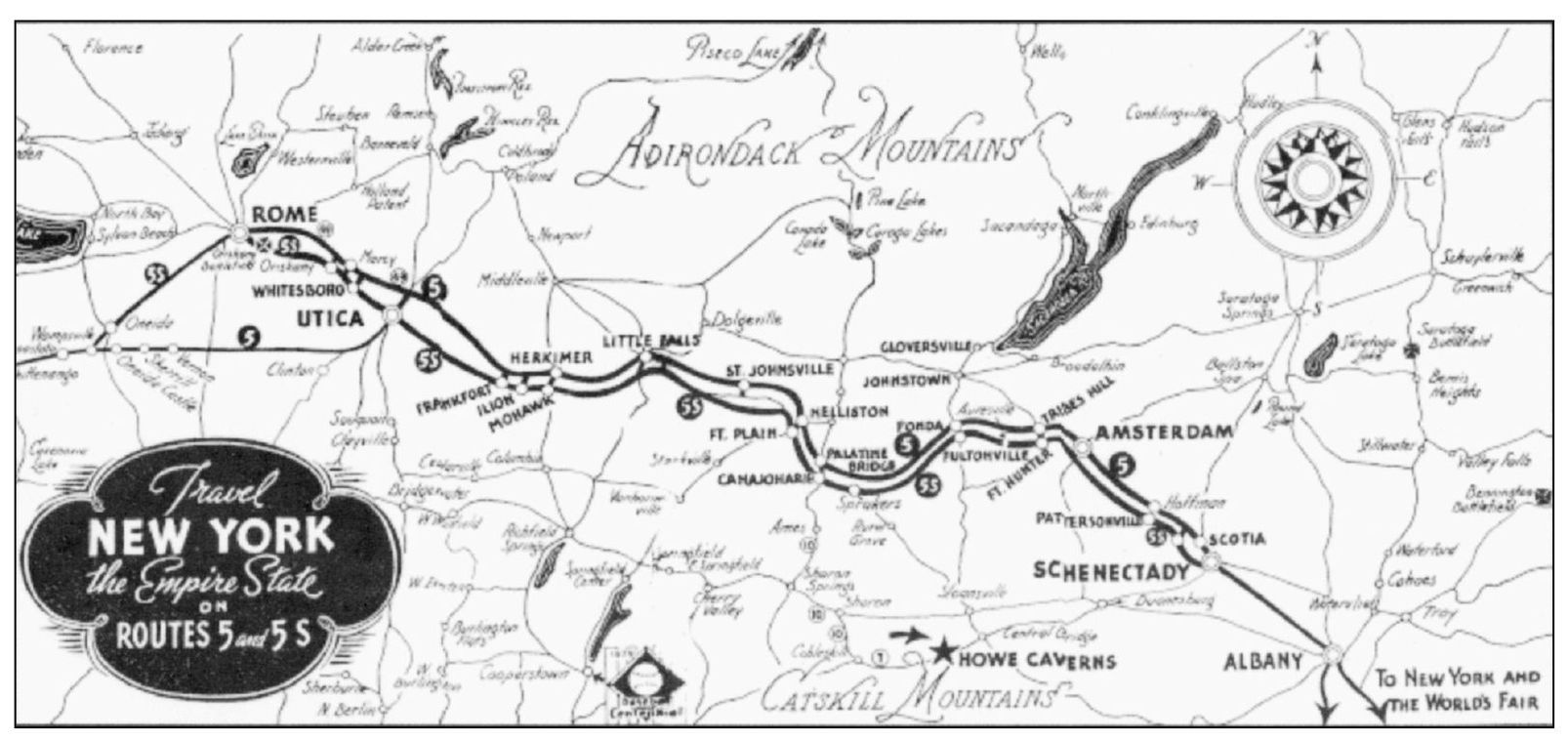

This 1939–1940 New York State tourism map shows Amsterdam in its relative position as the “gateway to the Mohawk Valley.” Routes 5 and 5S mainly follow the paths of the Mohawk and Great Western Turnpikes, respectively, which were key to the opening of both the valley and the Western frontier. (Courtesy of Montgomery County Department of History and Archives.)

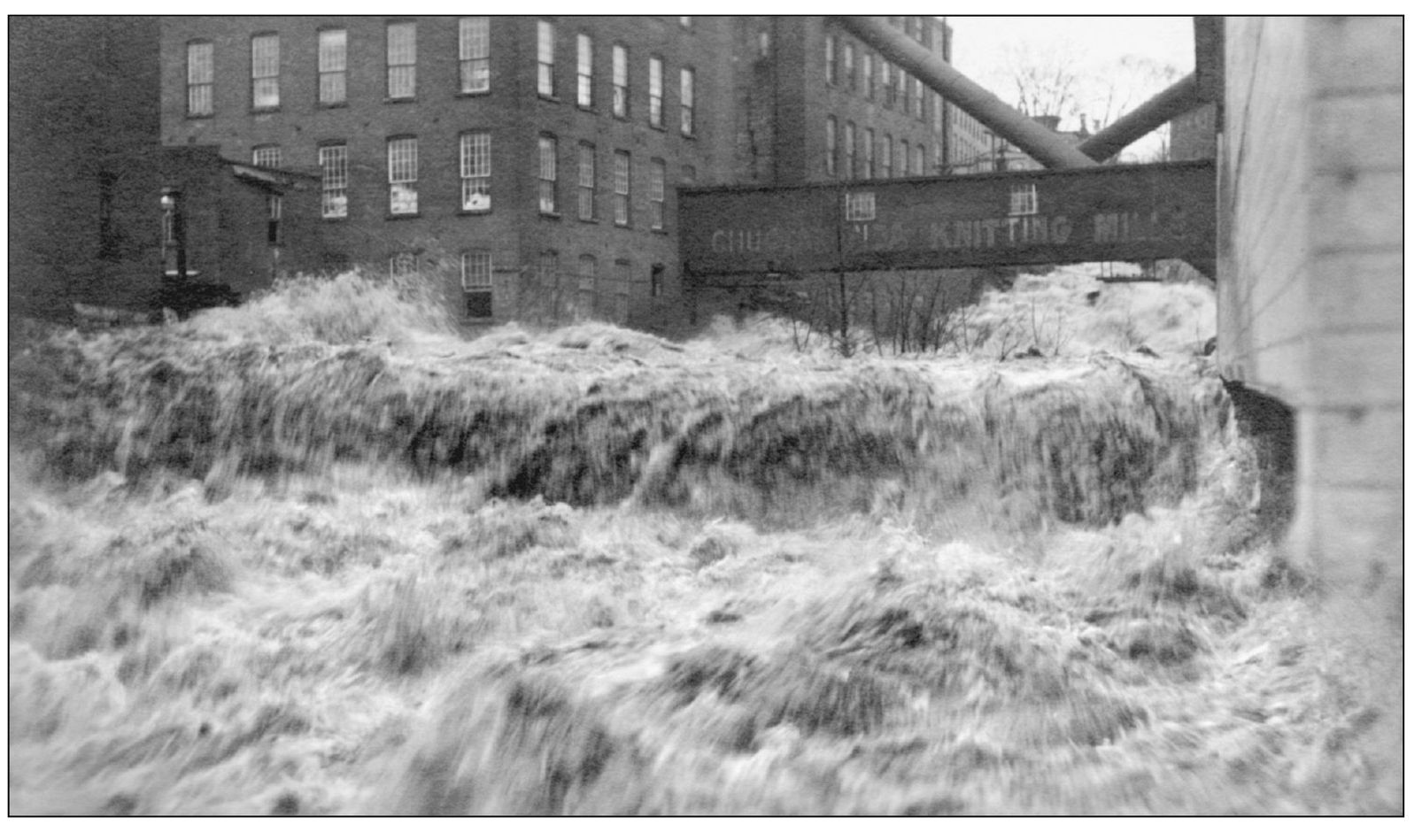

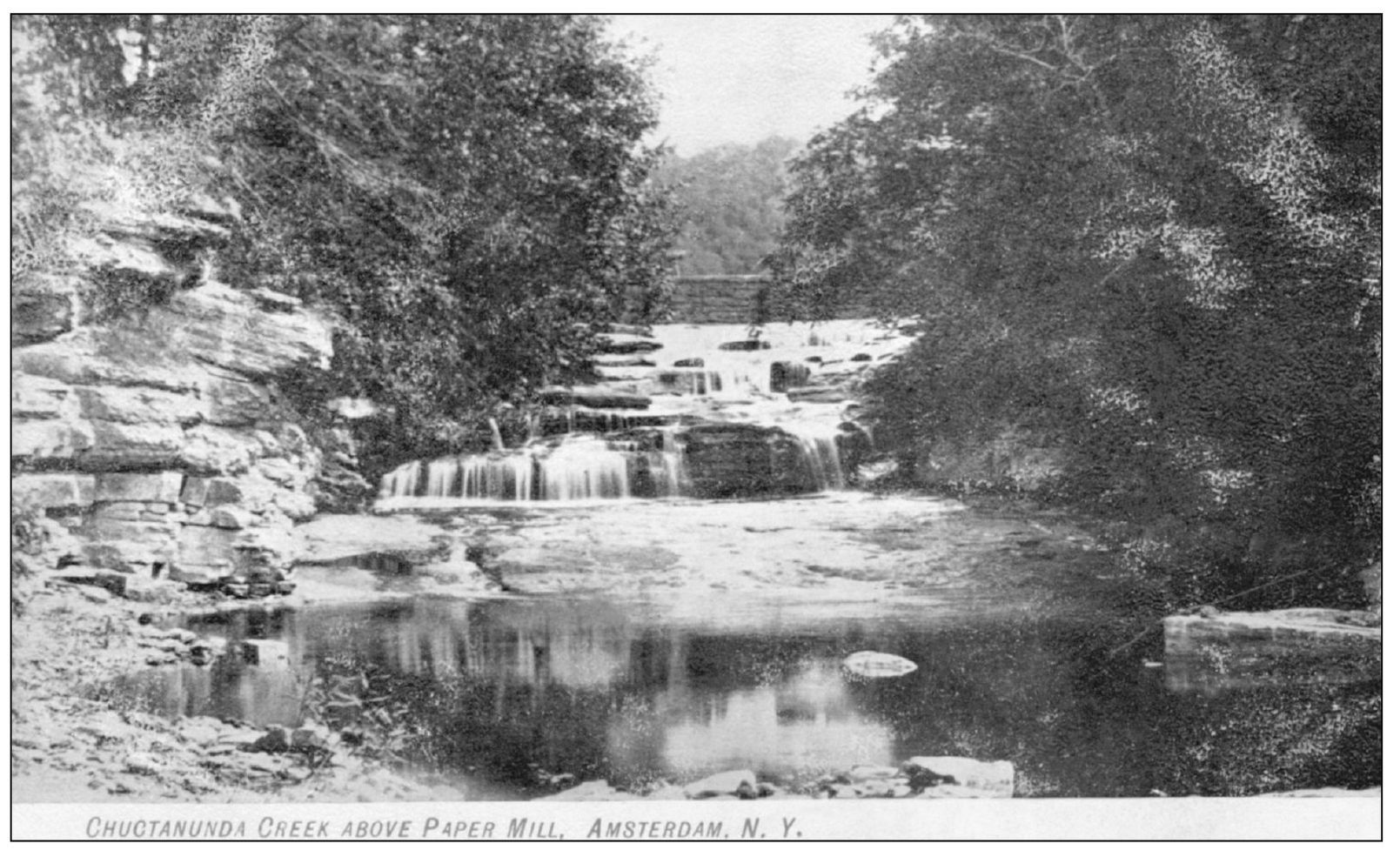

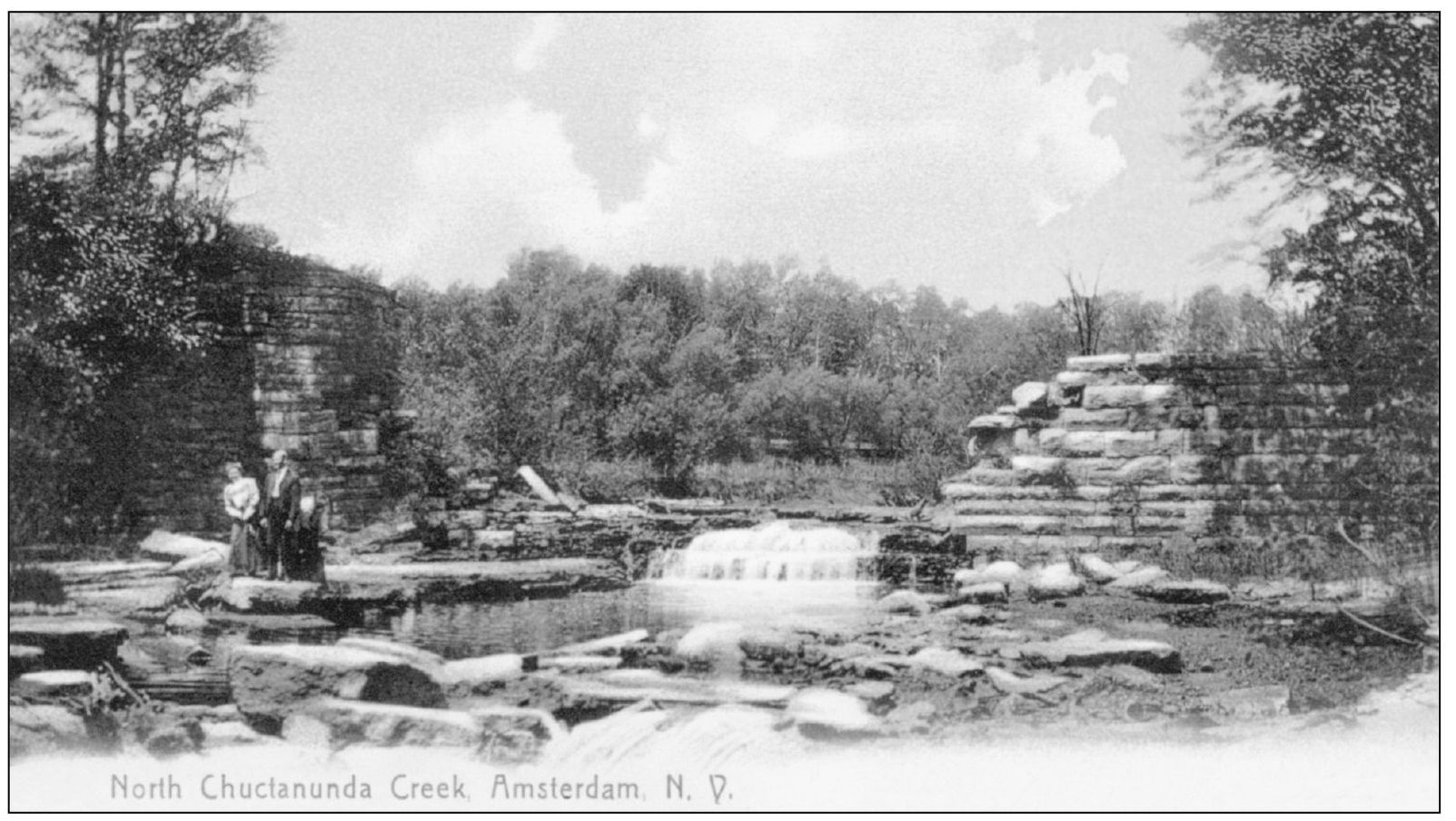

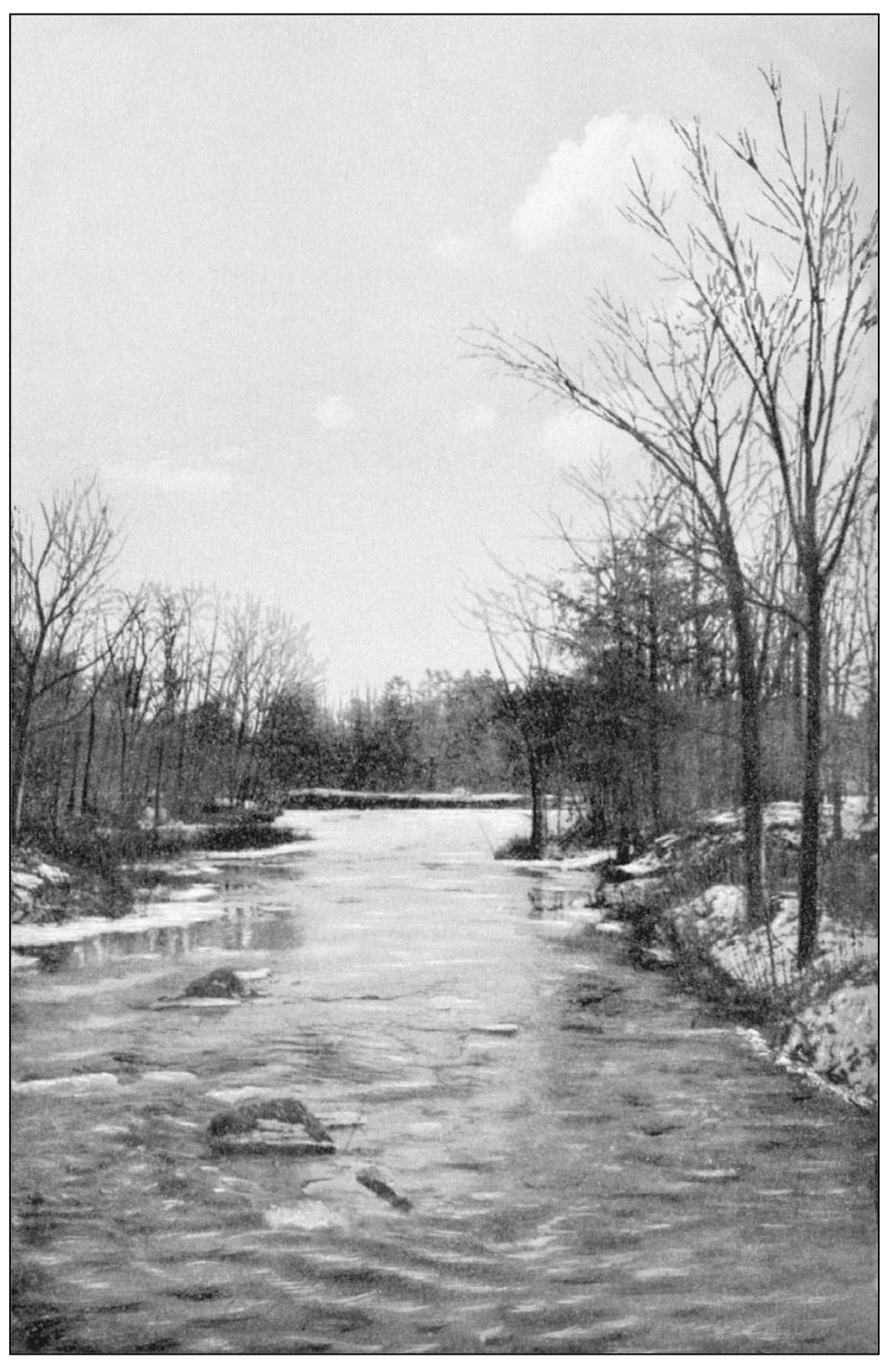

These two postcards, photographed northward from nearly the same position, demonstrate that the very thing that makes the Chuctanunda Creak beautiful and useful also makes it dangerous. Regarding the storm that created the rushing waters of the image below, one Amsterdamian wrote on her postcard, “Fear and excitement. Schools, Mills, stores dismiss in fear of the reservoirs. Wed night residents in the path notified to leave homes. Fire hydrants opened relieved pressure [sic].”

The Chuctanunda Creek is a source of both beauty and power along its 17-mile course from Galway Lake to the Mohawk River. Its power arises mainly from the 300-foot drop within its final 3 miles. The dam and falls shown above are just off Forest Avenue and originally provided power for the Stewart and Carmichael and later the Smeallie and Voorhees paper mills.

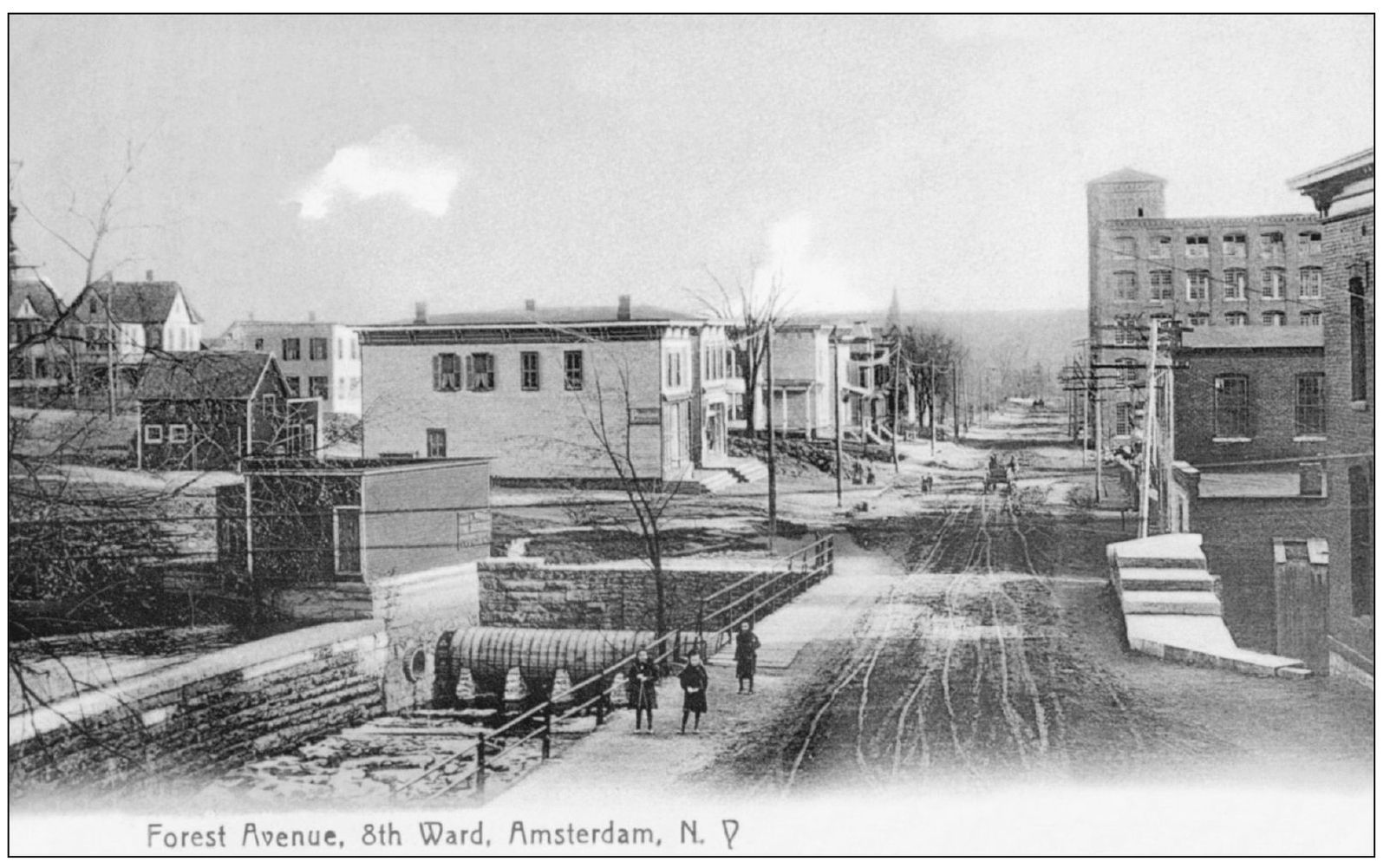

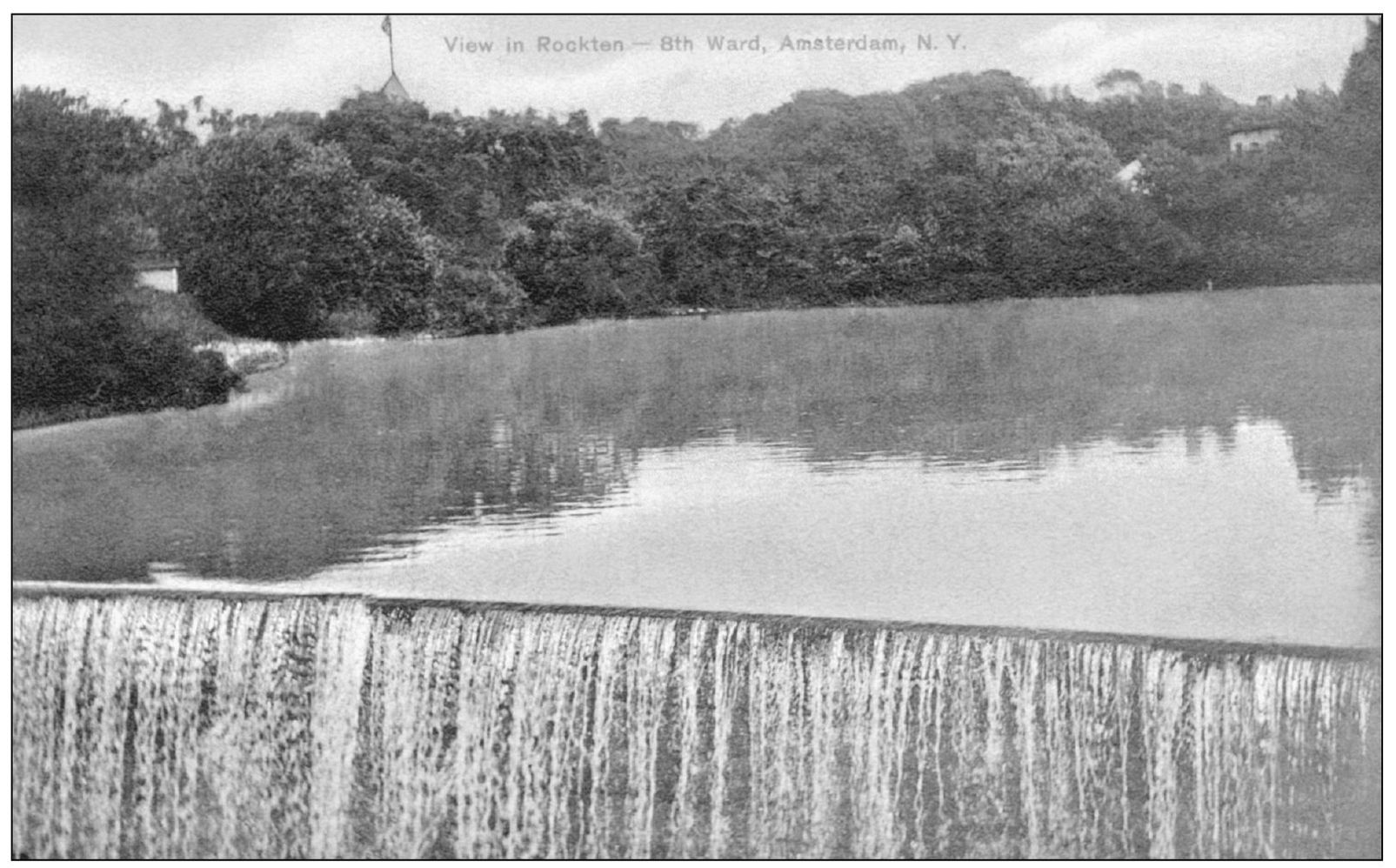

Rockton (originally Rock City) was a hamlet north of the city line when Amsterdam was chartered as a city in 1885. Rockton became the eighth ward of the city with two aldermen joining the common council in the spring of 1901. The dam at the right, remnants of which are still visible, supplied water to the McCleary, Wallin, and Crouse carpet mills.

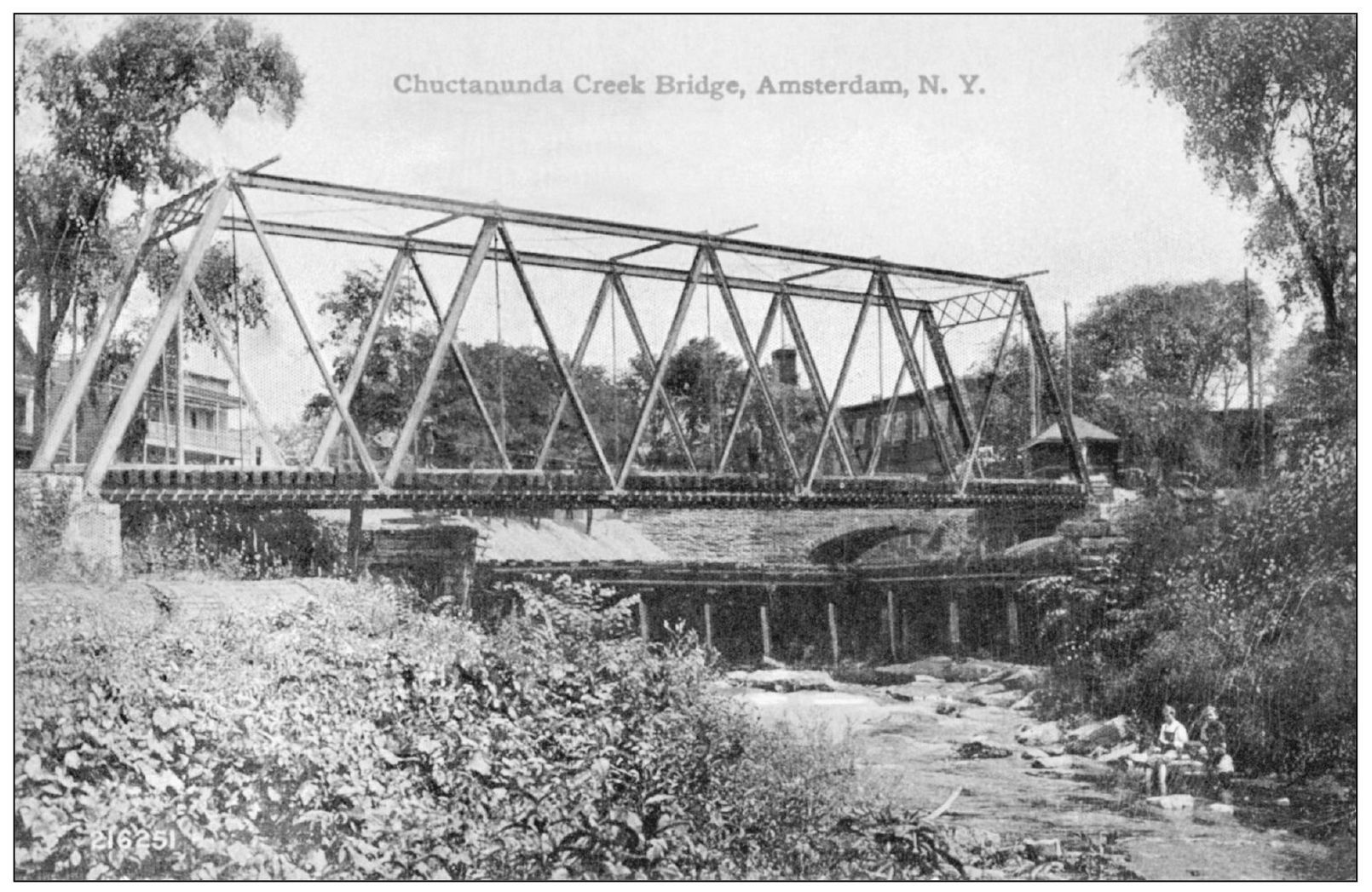

This is the trolley bridge crossing the Chuctanunda Creek from Lyon Street to the Rockton trolley wye. The milldam and penstock visible at left center are taking water to the L. L. Dean Park Spinning Mills.

The power of the Chuctanunda Creek was harnessed by a series of dams along its course through the city. This dam, just north of the Rockton wye bridge, provided power for the textile and box mills along the east side of the creek and Hewitt Street.

Many residents of Amsterdam are unaware of the creek’s beauty and that it winds continuously through the heart of the city and beyond. Periodic tours and lectures about its history, geology, and wildlife have rekindled awareness, and many hope someday that a nature and recreation trail can be established along its length.

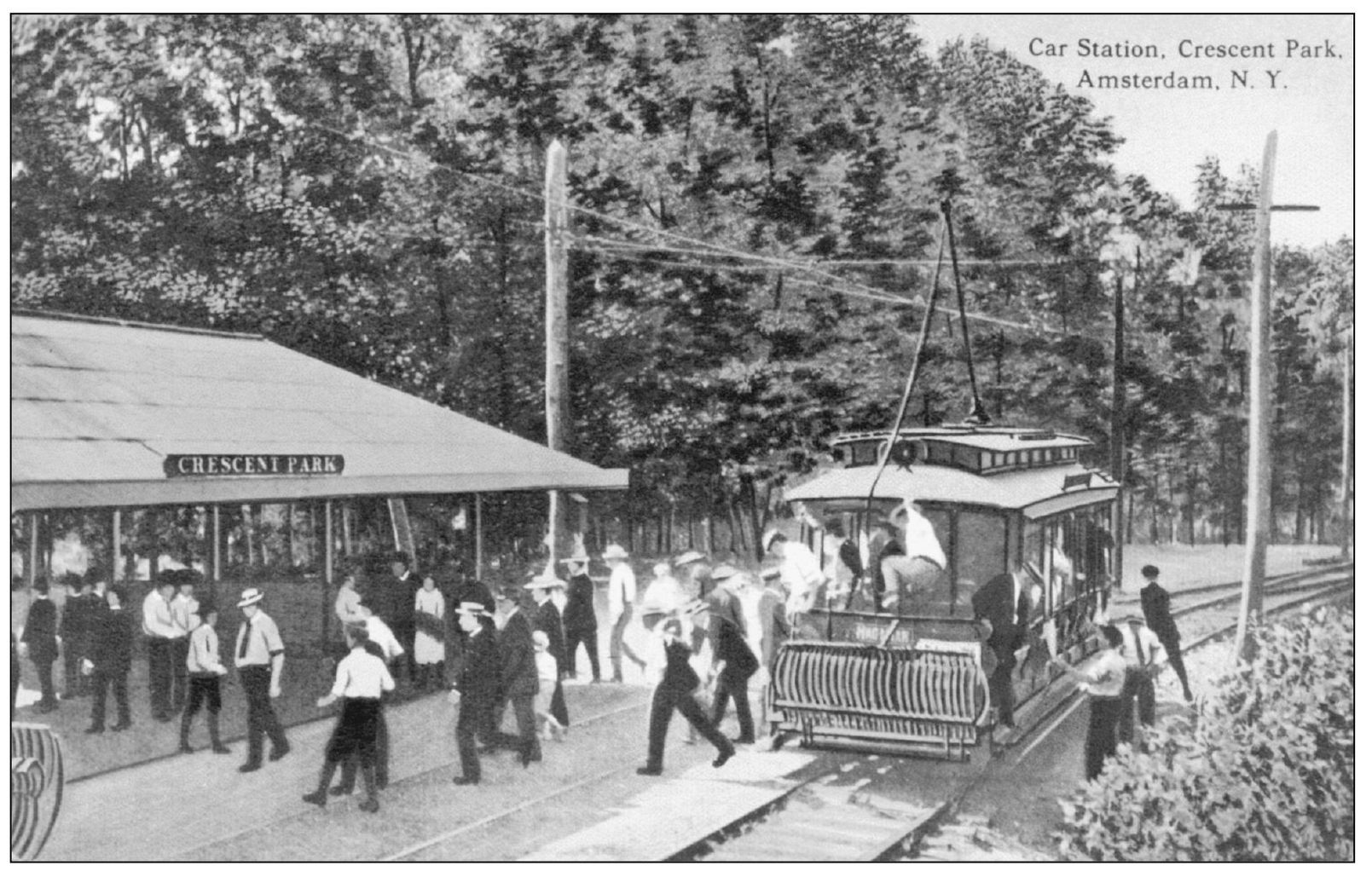

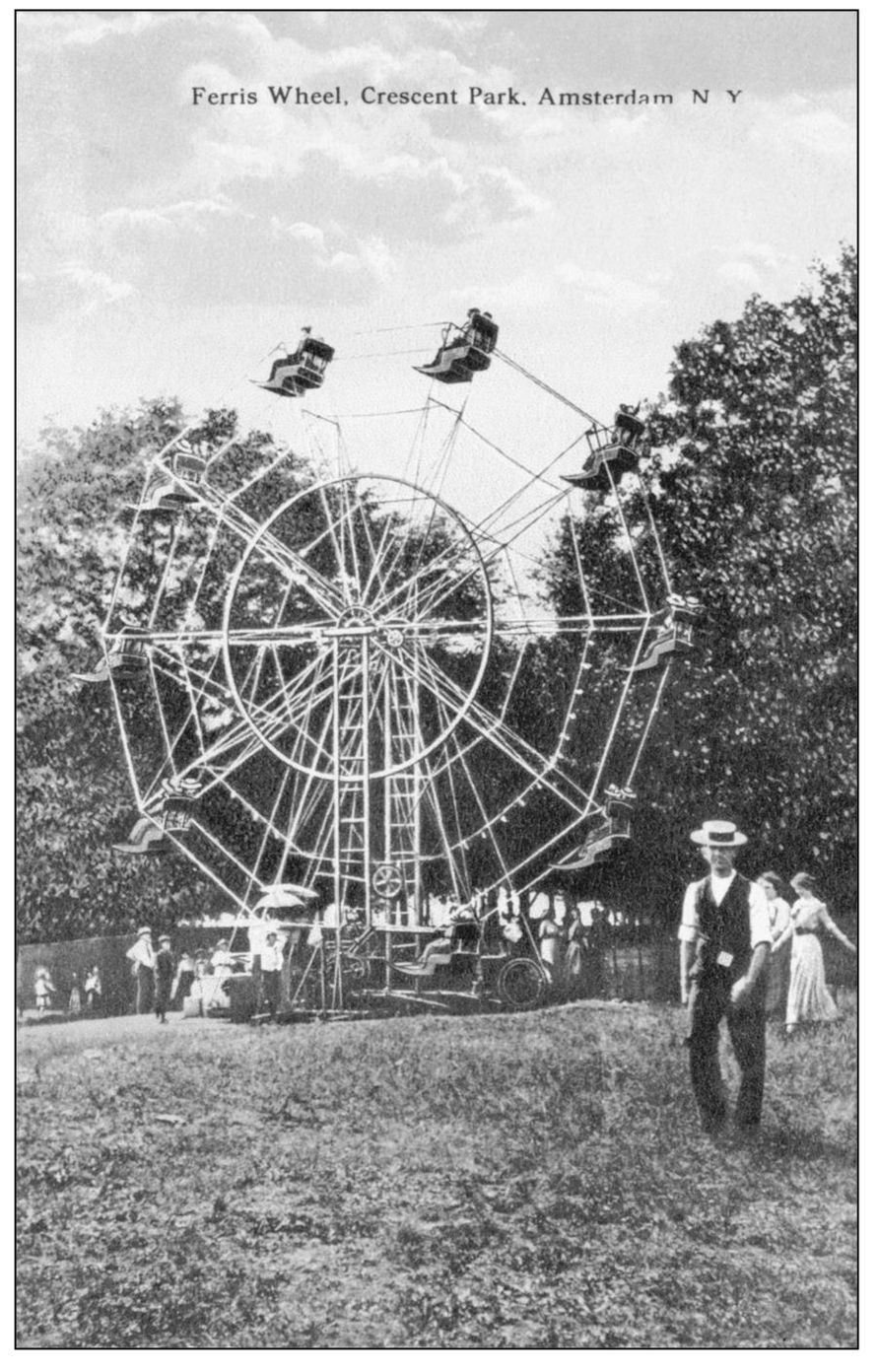

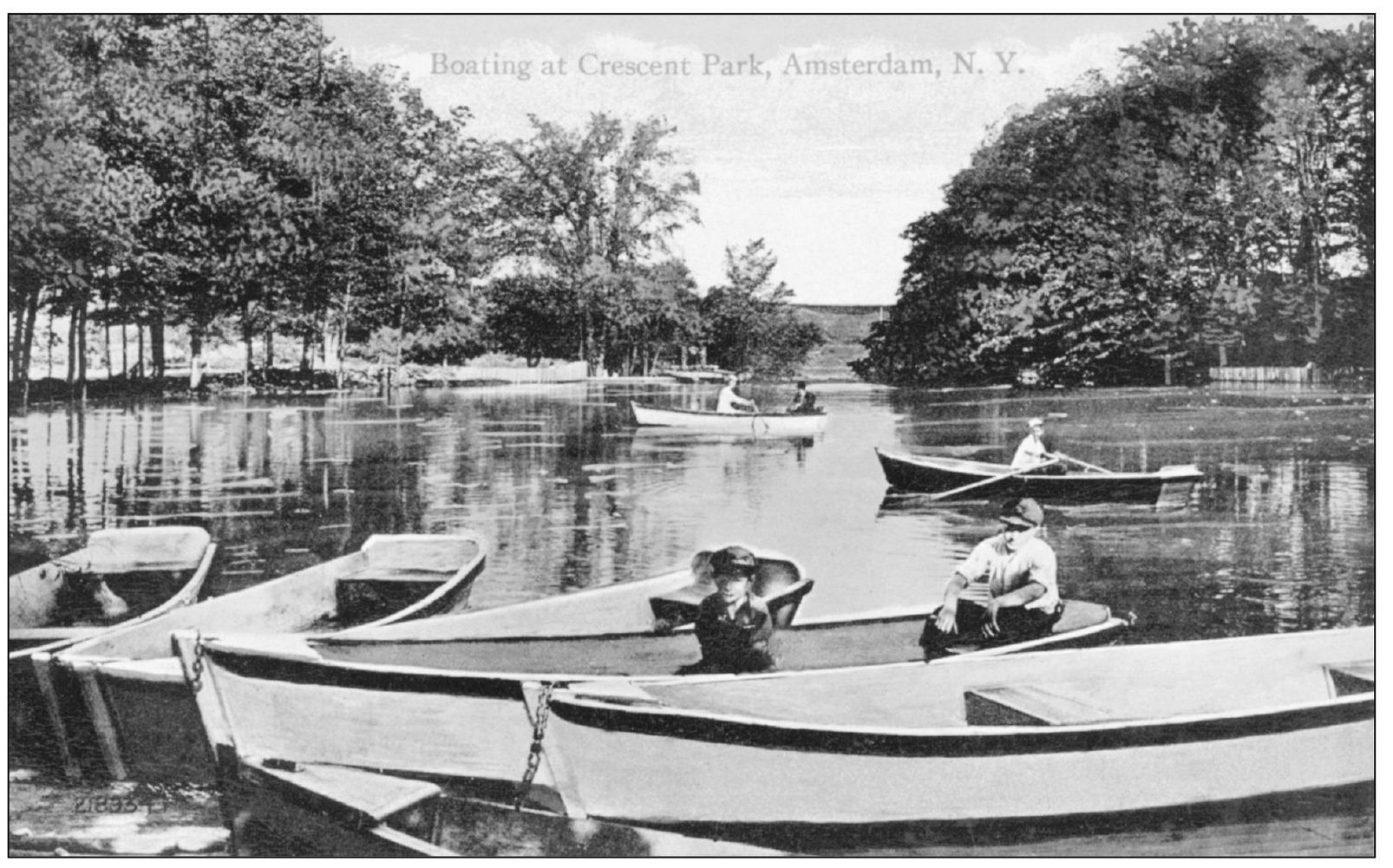

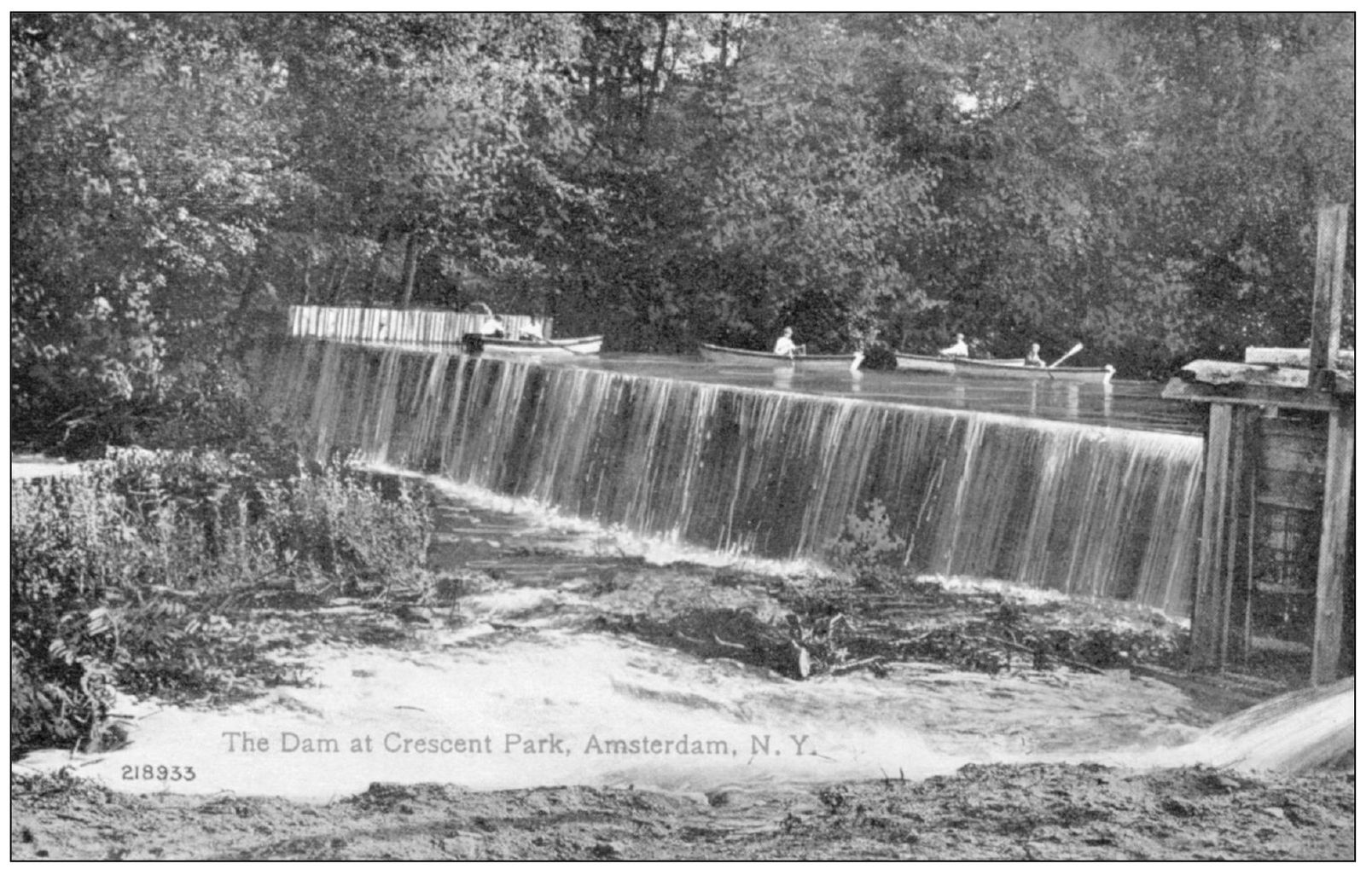

In 1914, a private realty company involving the McCaffrey brothers (see page 26) developed an area east of Locust Avenue as Crescent Park, an amusement park. Bordering the Chuctanunda Creek and served by the Hagaman line of the Fonda, Johnstown, and Gloversville Trolley, the park was a popular destination for those seeking escape from the noise of the looms and weariness of a six-day workweek.

In 1923, management of Crescent Park fell to Fred J. Collins, who purchased the property and renamed it Jollyland. He also added more rides and games, including a miniature railroad.

Subsequently purchased by a leading manufacturer and renamed Mohawk Mills Park, the park was donated to the city and renamed Shuttleworth Park in 1977. Long gone are the lake and dam, replaced by more modern recreational facilities, including a minor league baseball stadium.

Other than a few large stone blocks behind the baseball field’s center field, little remains today of the Crescent Park Dam, one of the few dams on the Chuctanunda erected for recreation rather than industry. Some of the former boating area became a winter ice skating rink.

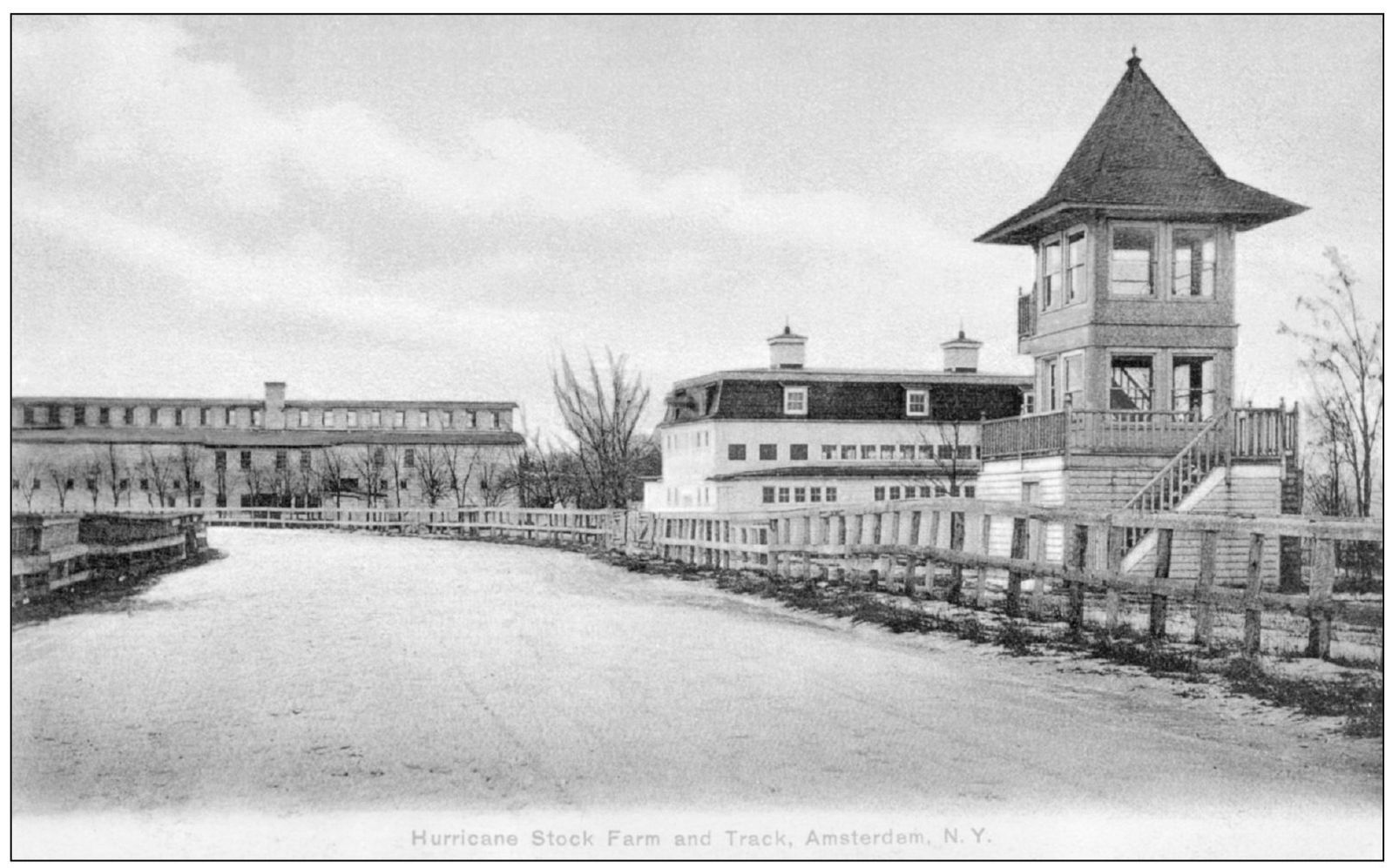

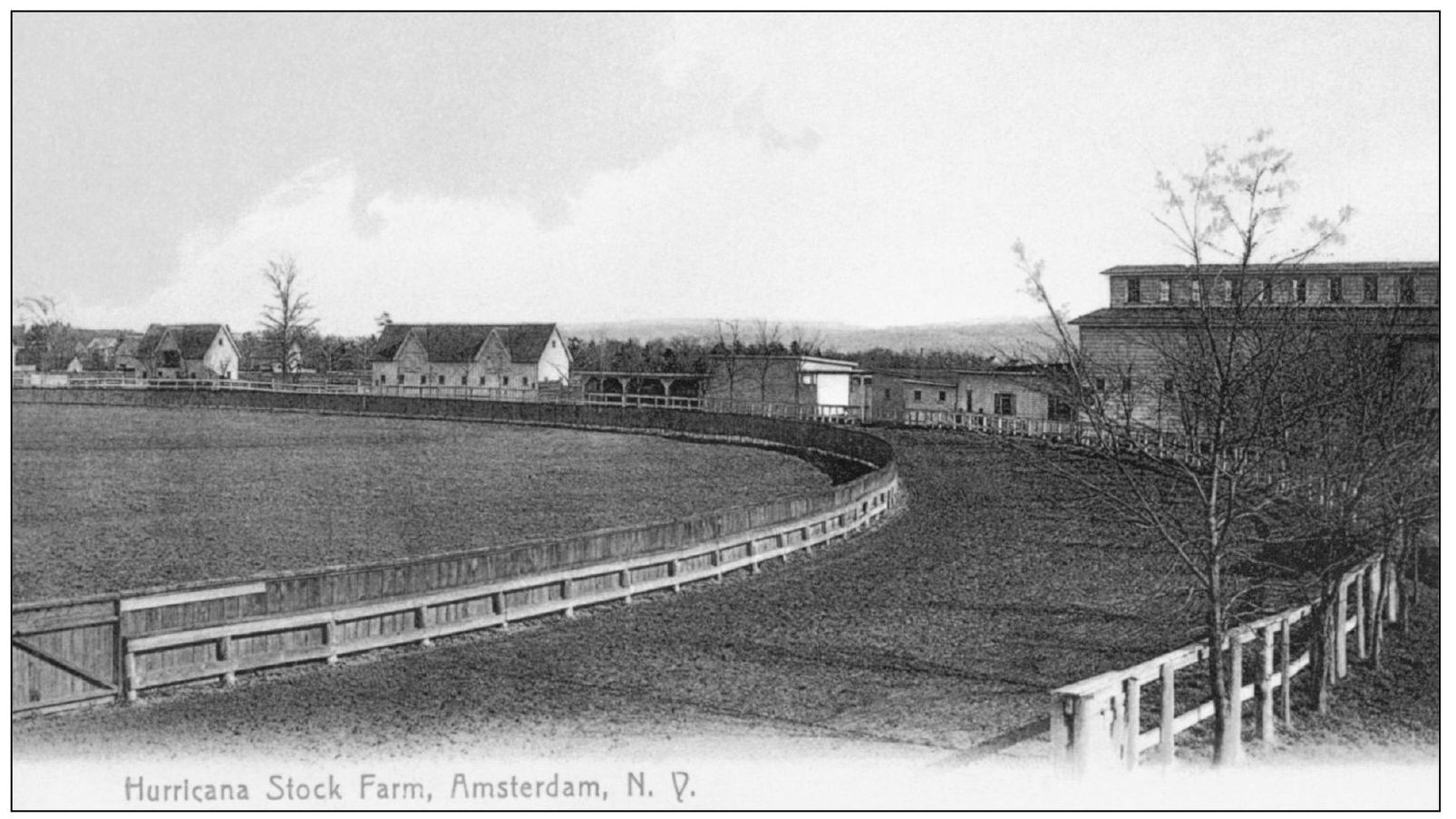

In the 1870s, mill owner Stephen Sanford took his doctor’s advice to get a hobby and began buying up land along a windy ridge north of the city to create a farm to breed horses. He called it Hurricana Farm. In this view, the outdoor exercise track is seen in the foreground, and from left to right are the broodmare barn, the stallion barn, and the judges’ stand. For several years in the early 20th century, Sanford invited employees to a yearly picnic at the farm, complete with exhibition races.

The farm not only supported the breeding of Sanford’s own horses for racing at Saratoga and elsewhere (including the 1916 Kentucky Derby winner), but it also contracted out its services to other breeders. Thus in the 1930s, the name was changed to Sanford Stud Farms. One expert estimates that the majority of modern Kentucky Derby winners can trace their lineage through this farm.

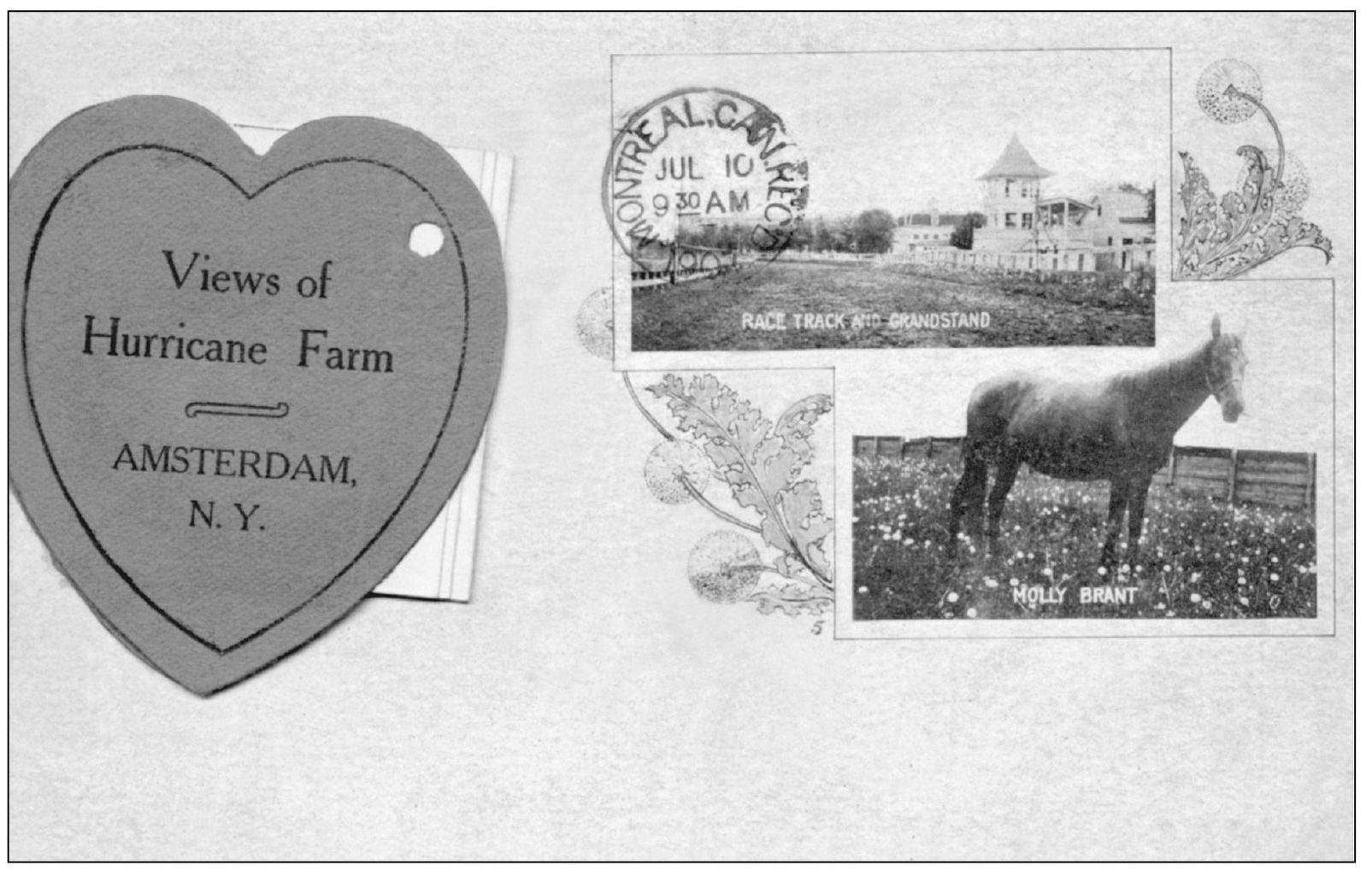

Sanford made a practice of naming his most beloved or promising horses after local features or persons. This rare Valentine’s Day card shows one such, Molly Brant, who was named after the Native American wife of Sir William Johnson (see page 124). Other favorites who appear in a foldout strip behind the heart included Chuctanunda, Rockton, and Caughnawaga (the original name for the township including Amsterdam).

The farm closed in 1977, and portions were sold to make shopping centers along Route 30. The broodmare barn and several structures were ceded to the Town of Amsterdam, and a friends group is preserving them. These monuments to Sanford’s favorite horses once adorned the farm. Contrary to local legend, these are not grave markers of horses, including the 25 horses killed in a barn fire in 1939. Only one horse, Monarchist, is known to be buried here.

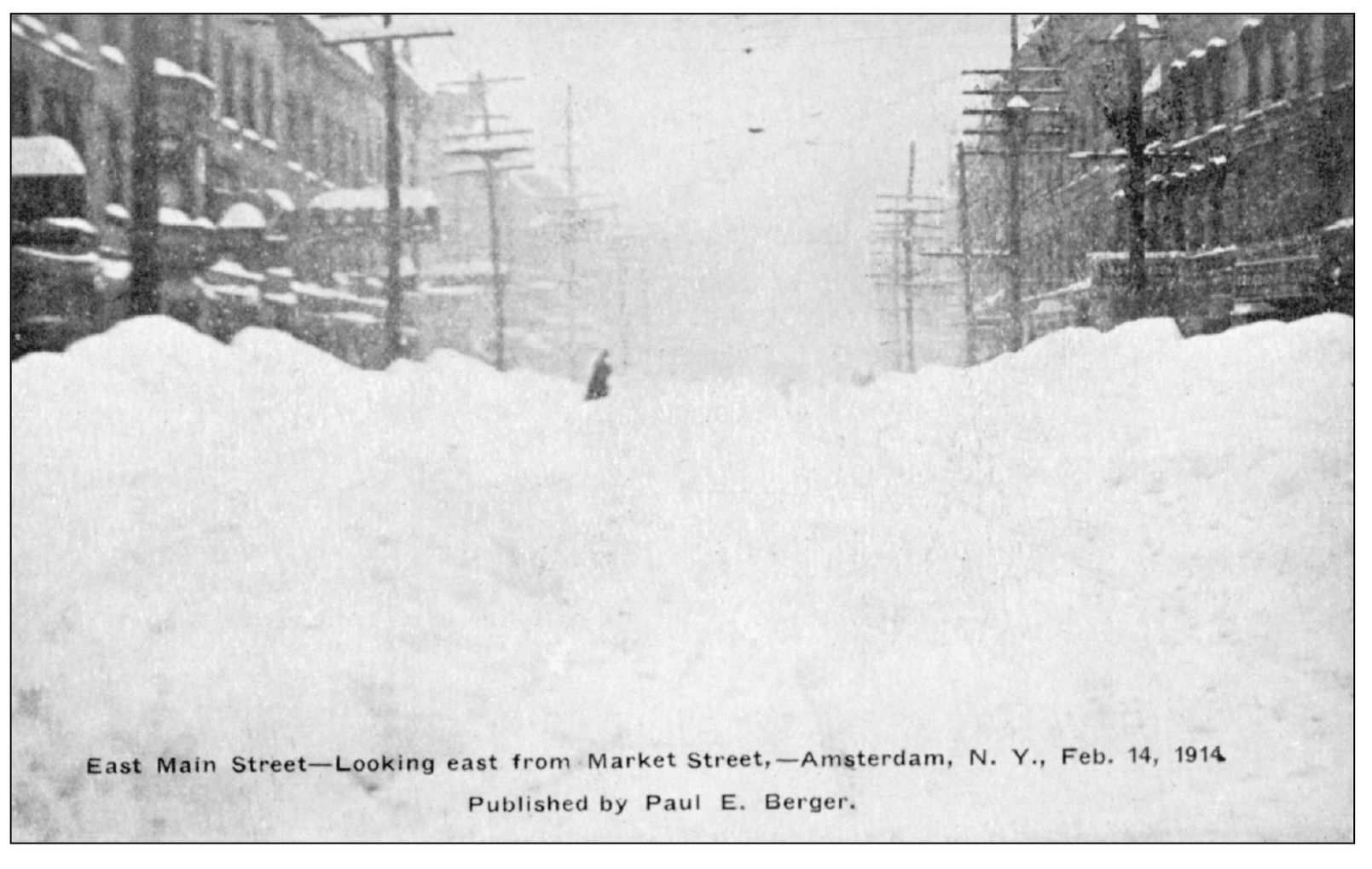

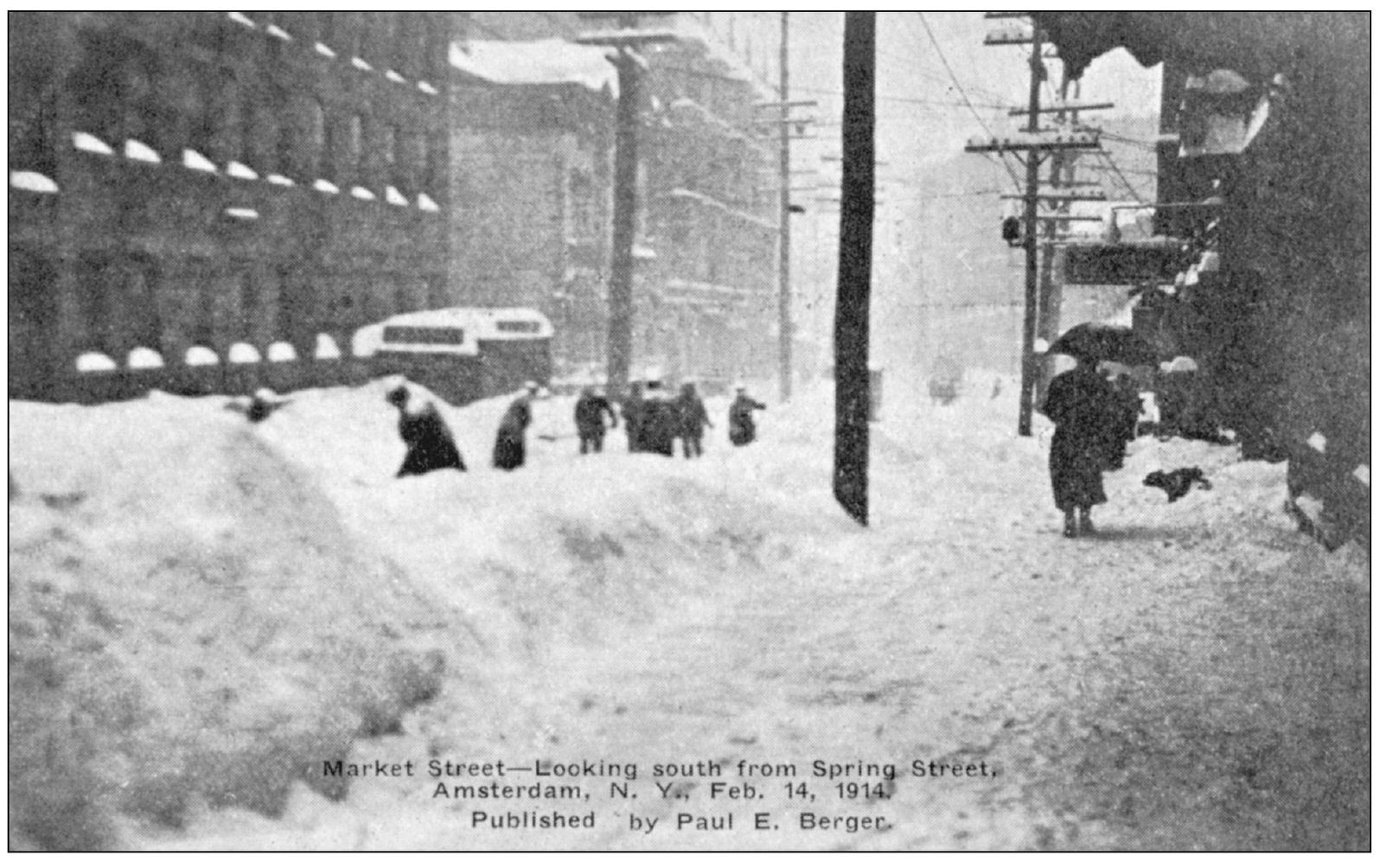

People attempt to cross downtown streets in the aftermath of the Valentine’s Day blizzard of 1914. Winters may be harsh or moderate, but throughout its recorded history, Amsterdam has never been more than 10 to 20 years away from a crippling snowstorm. Snow removal remains a make-it-or-break-it issue for each mayor of Amsterdam.

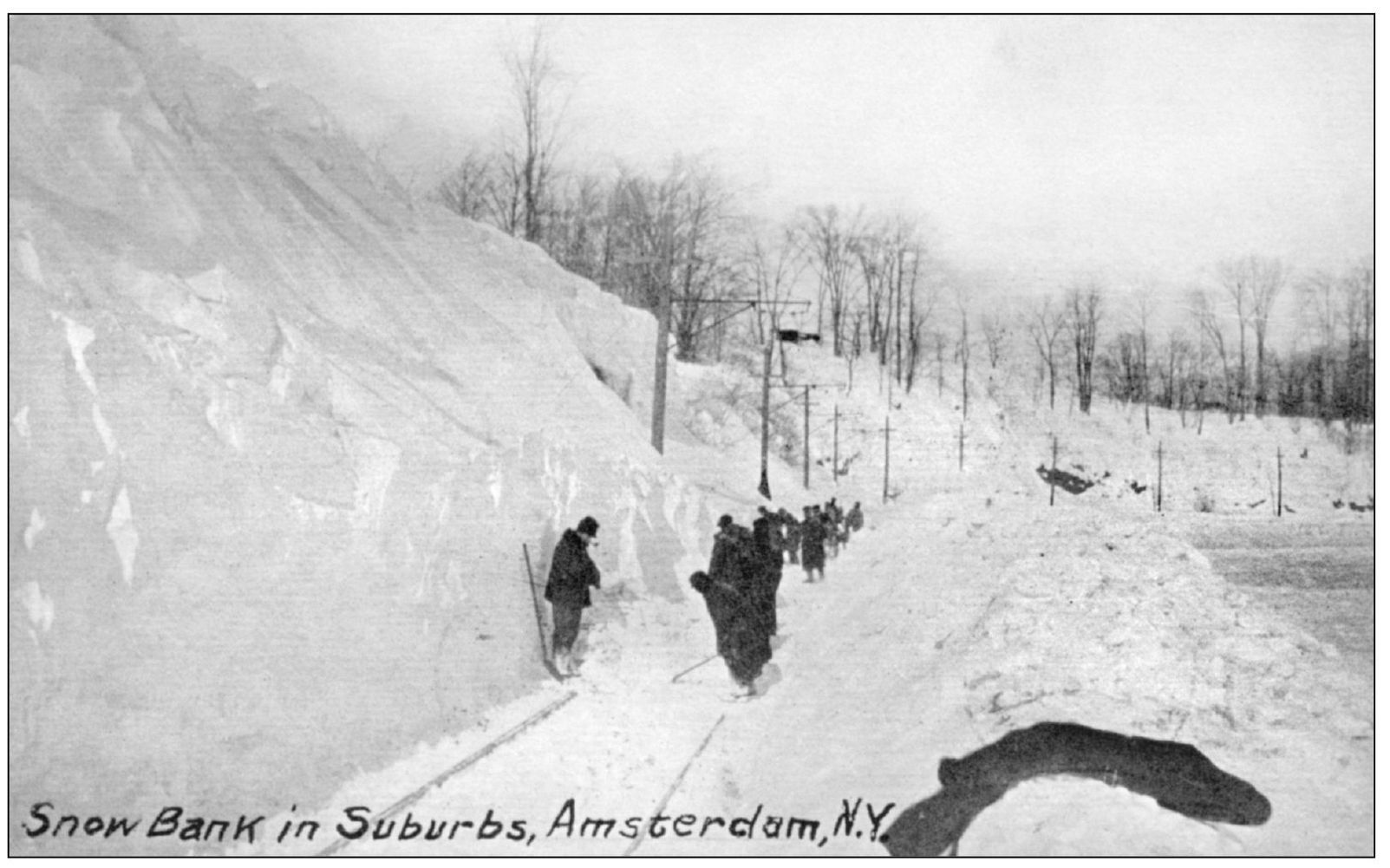

Work crews from the Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Rail Road dig out trolley lines on the outskirts of the city in 1914. This railroad was equipped with snowplow machinery, but even after they had passed through, individual shoveling crews were required to complete the clearing of the tracks.

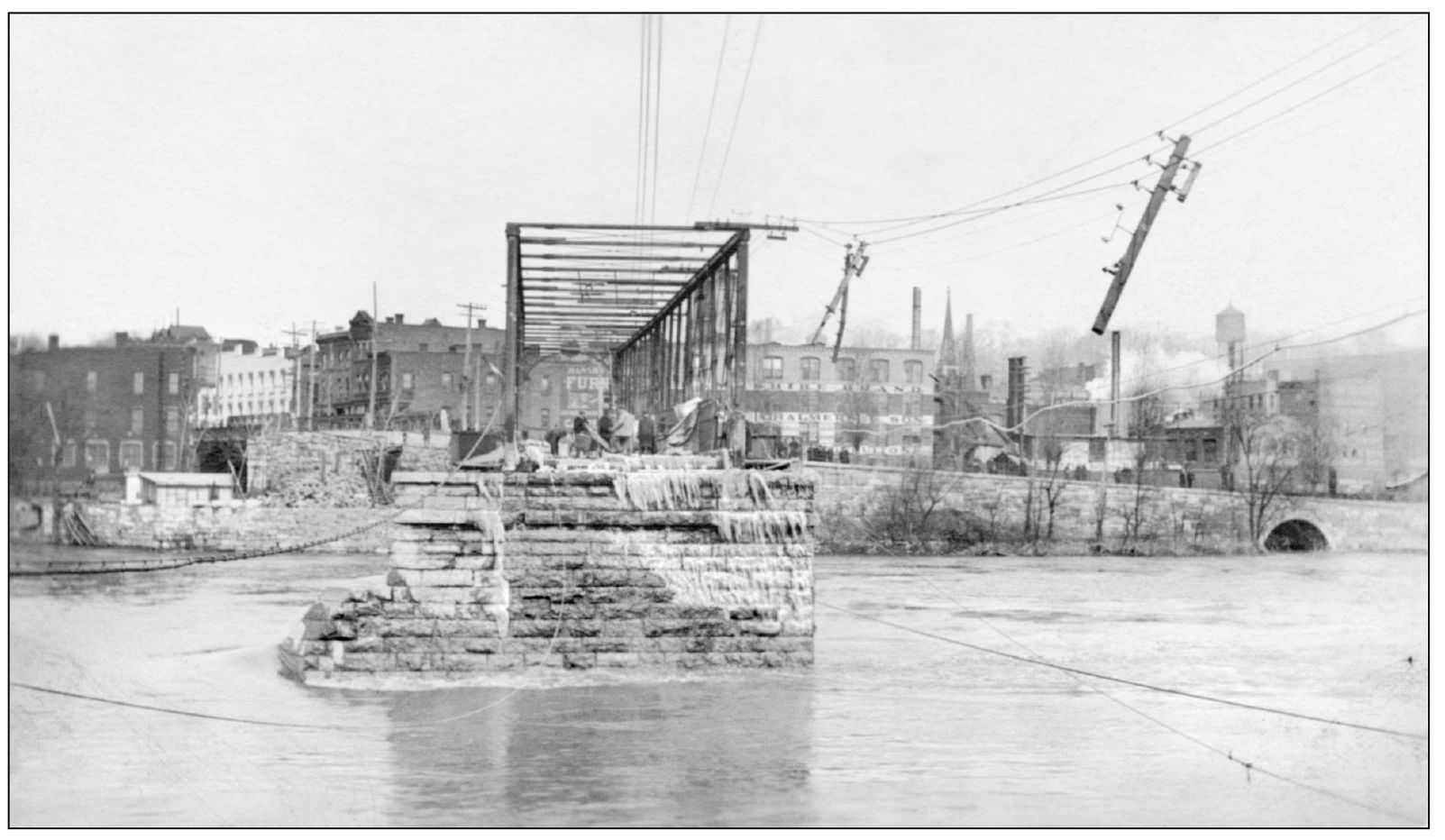

For many years, March 27 was “bridge day” in Amsterdam. On March 27, 1913, floodwaters tore the southernmost span of the bridge over the Mohawk River from its footings. Exactly one year to the day later, the trestle erected as a repair was demolished in another flood. Here workmen inspect the damage after the first flood.

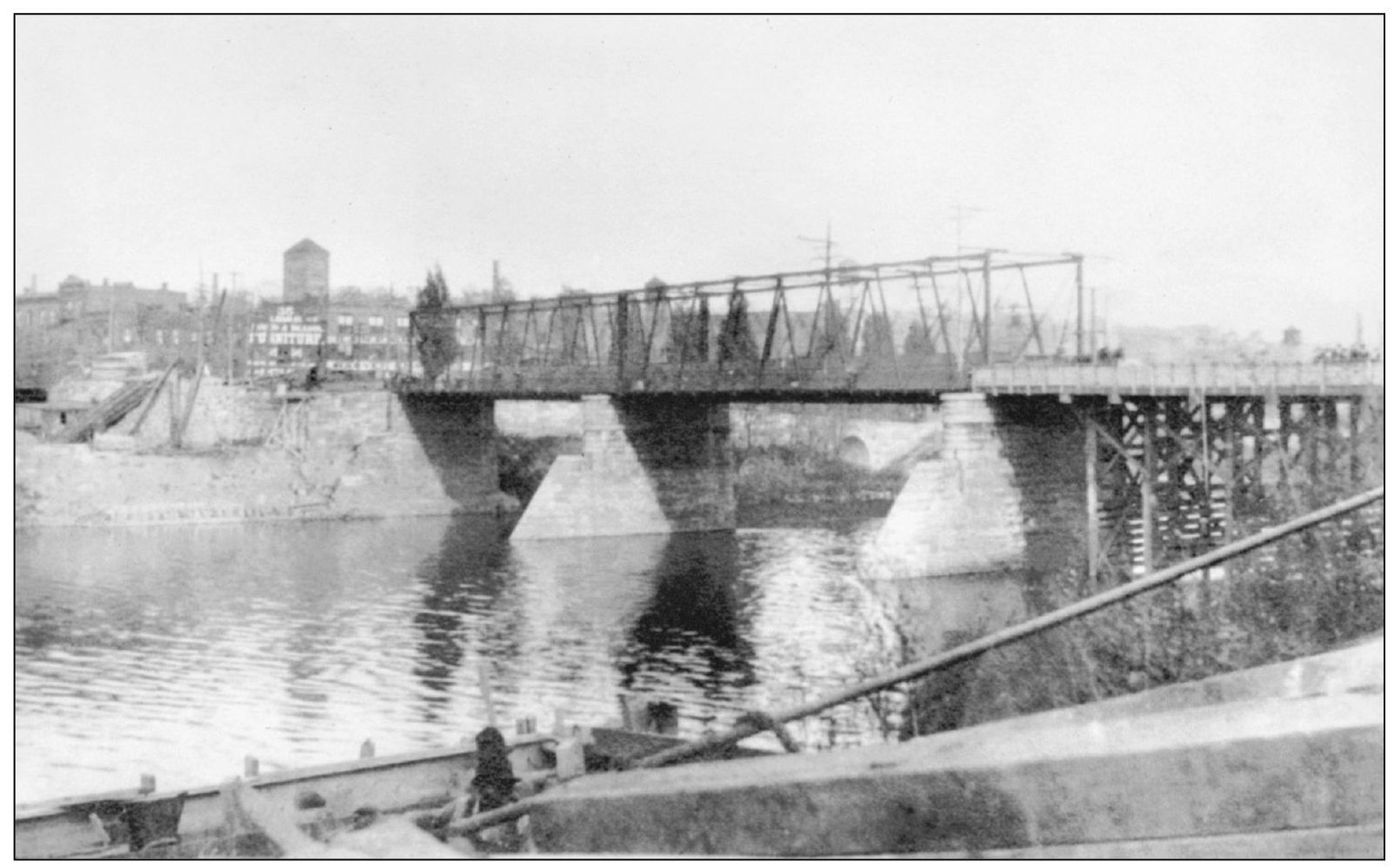

In this image, the 1914 repair trestle is emplaced. This was destroyed on March 27, 1914. After each time a span went down, individuals and businesses were left to find their own ways across the river either by going to another crossing up- or downstream or by using the temporary ferry services that sprang up. At least two deaths were caused by small boats being used as ferries in bad weather.

Here is the bridge as it was further damaged in 1914. In the foreground is a popular hotel and restaurant operated in the south side by an Italian immigrant family. On the north bank, the Chuctanunda Gas Light Works are visible. After the 1914 destruction, no more attempts were made to effect repairs to the 1876 bridge; a new and stronger one was built in 1916.

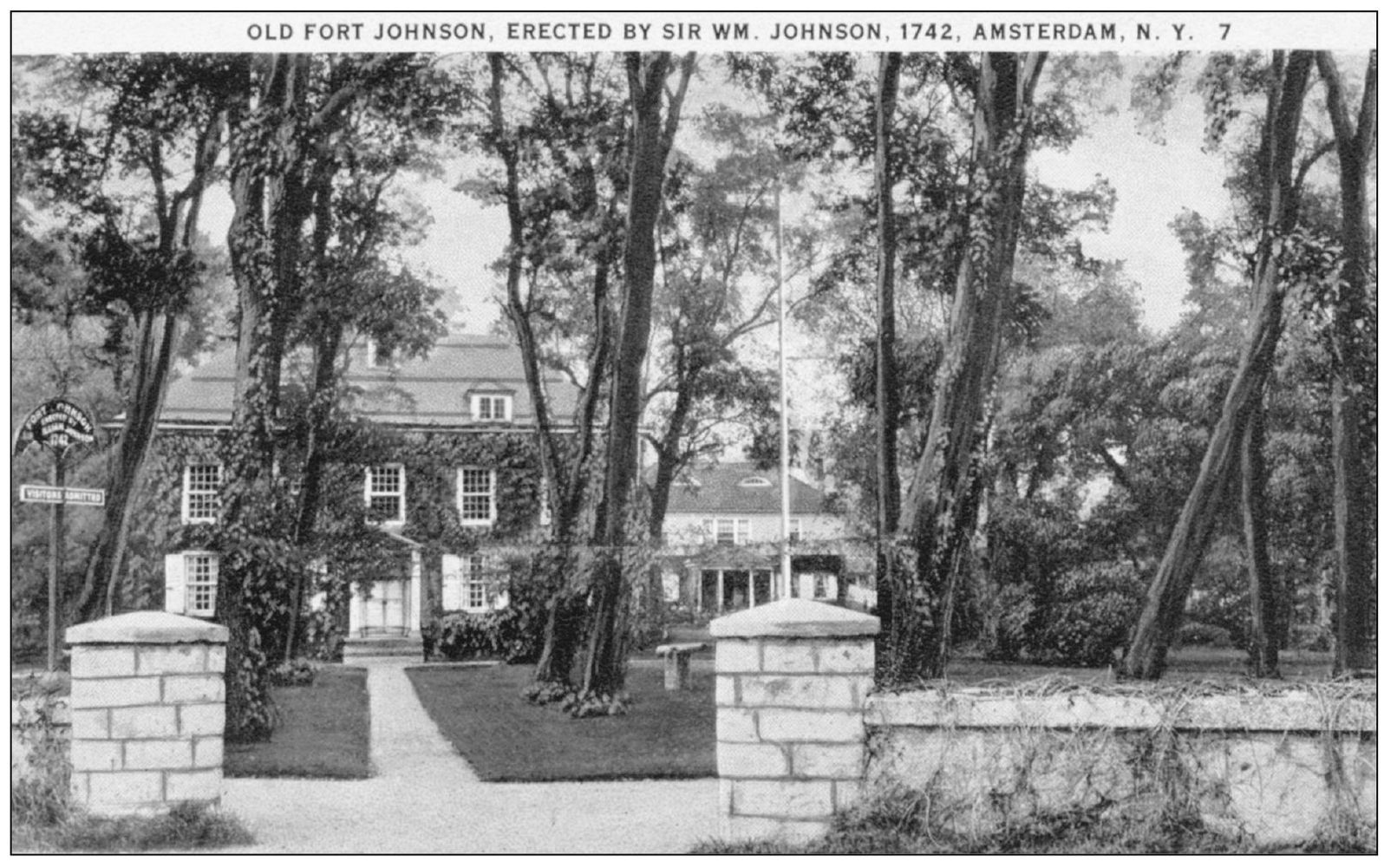

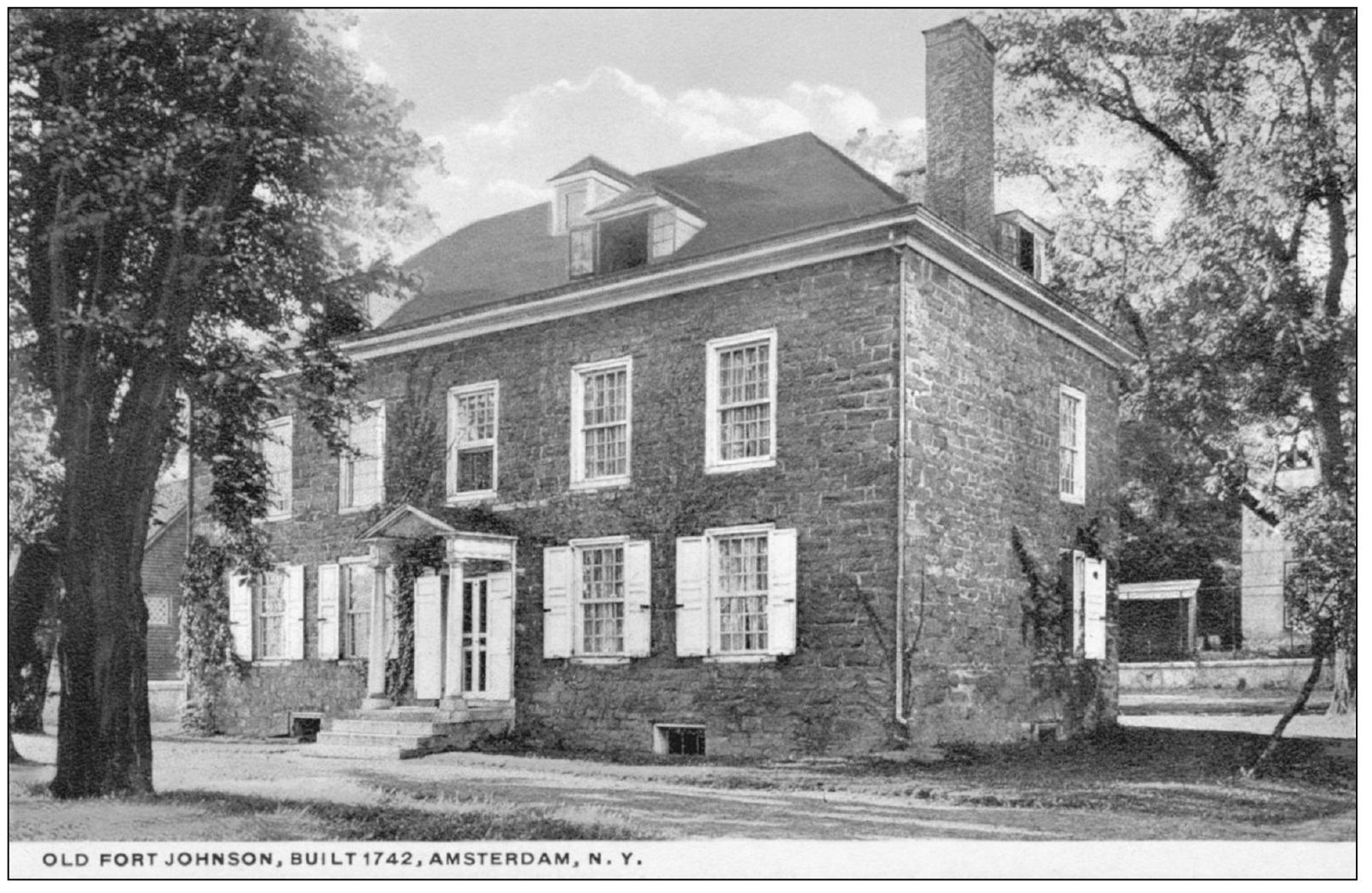

After immigrating to the colony of New York in 1739 to attend to his uncle’s land holdings across the Mohawk River from what became Amsterdam, William Johnson sought to obtain his own land and business opportunities on the north bank. Using his knowledge of and good relations with Native Americans, Johnson embarked on a career that brought him land, wealth, military honor, nobility, and the especial trust of many Native American nations and the king of England. This was his second home on the north bank, built in 1749. An earlier home was built in 1743 a mile closer to present-day Amsterdam. Today the house is extensively restored and open as a museum. Old Fort Johnson is a national landmark.

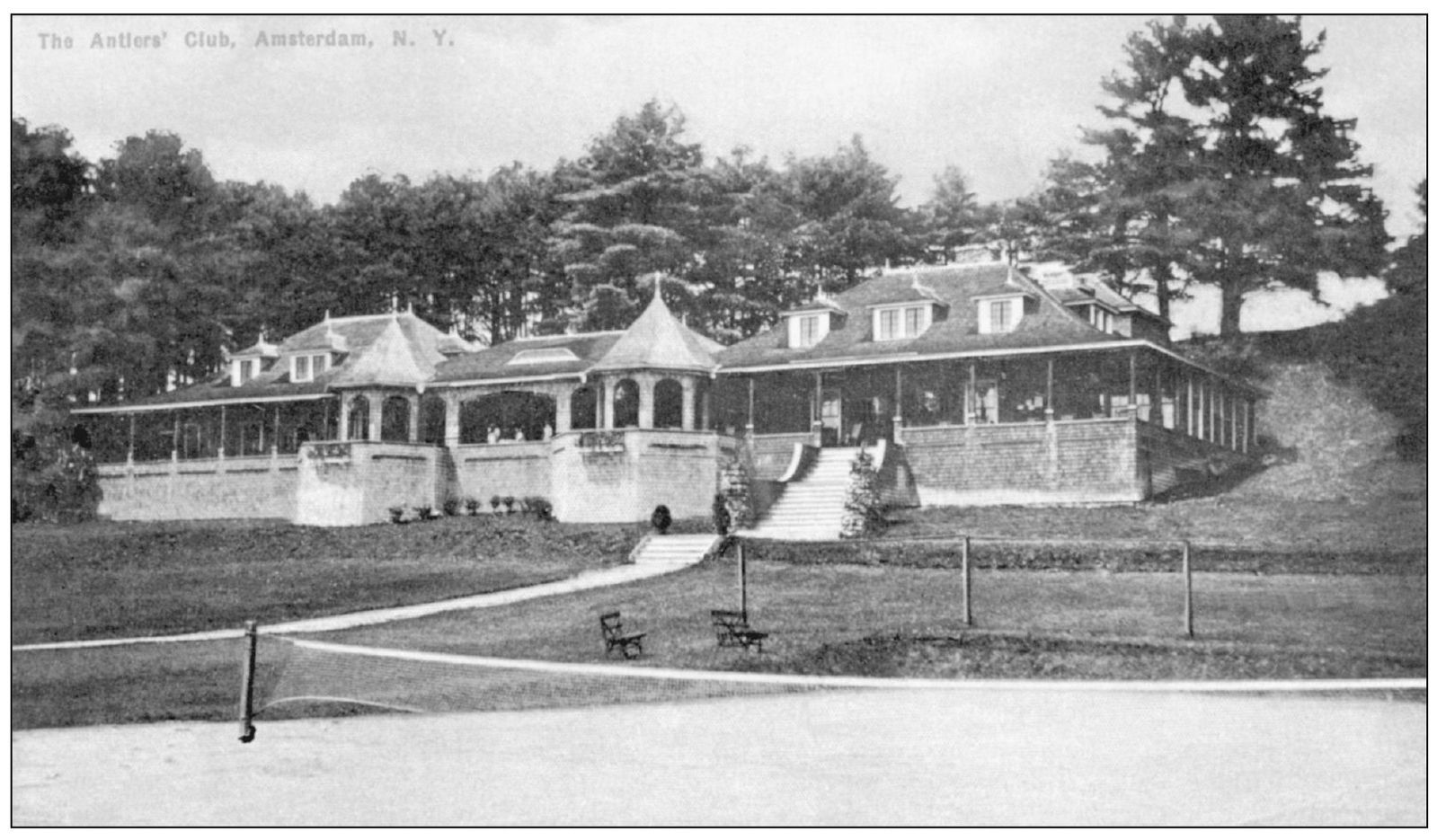

The Antlers was founded in 1900 as a private club for Amsterdam’s well-to-do. Membership was by invitation only and restricted to “eligible males of the county over 21 and of approved character.” With a professionally designed golf course and tennis courts overlooking the scenic Mohawk, it was the popularity of the clubhouse for social functions that lead to its expansion within four years of opening. The expansive clubhouse was destroyed by fire in 1965 and replaced with a smaller version.

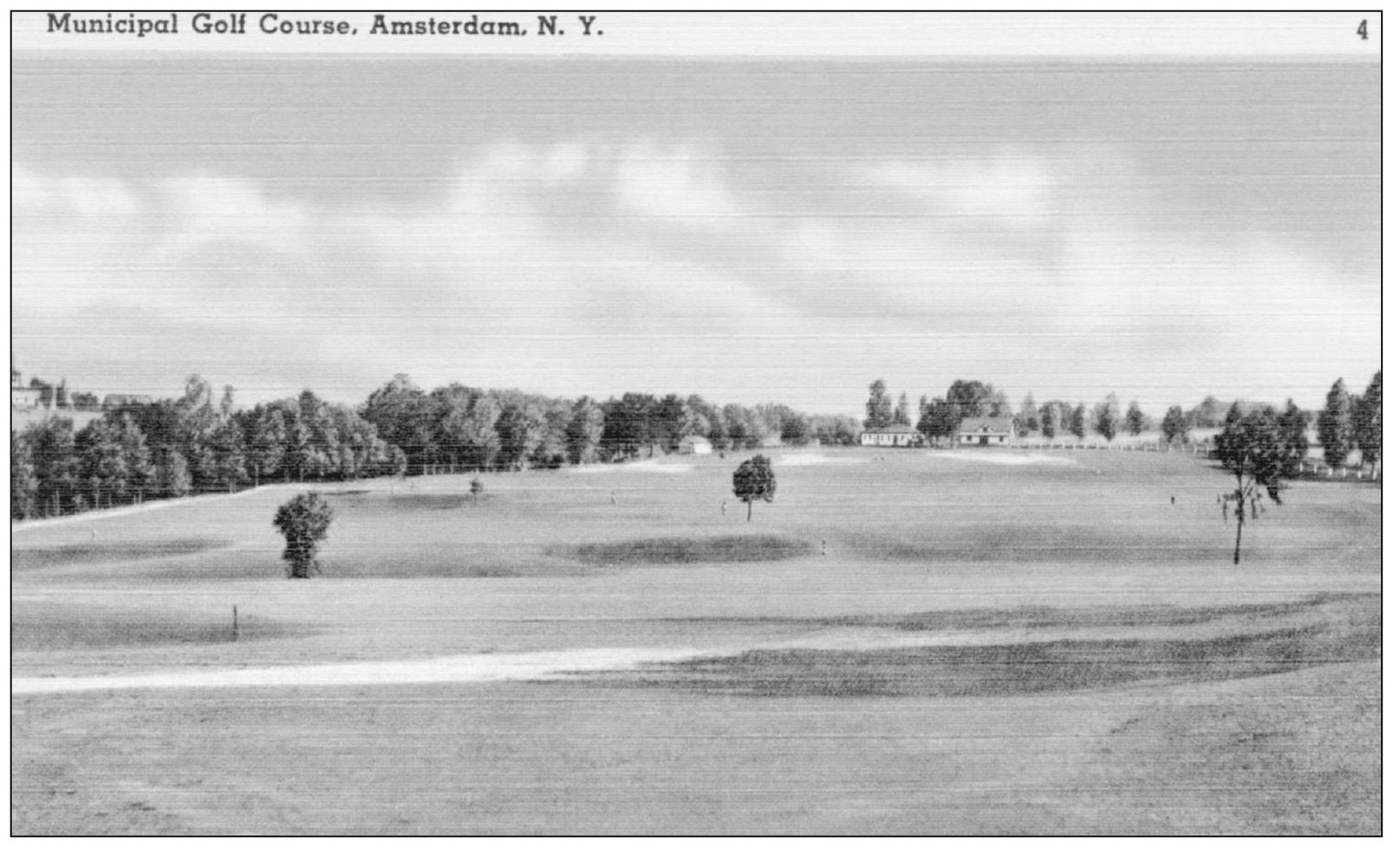

A golf course for Amsterdam had long been considered, and efforts commenced in 1929. Approximately 200 acres of farmland was purchased for $16,000. Federal Works Progress Administration funding paid for four-fifths of the construction costs ($123,000), and the Muni opened on July 19, 1938, with national titlists Gene Sarazen and Tom Creavy teeing off. Debate continues today as to the degree which the course should be supported by public funds.

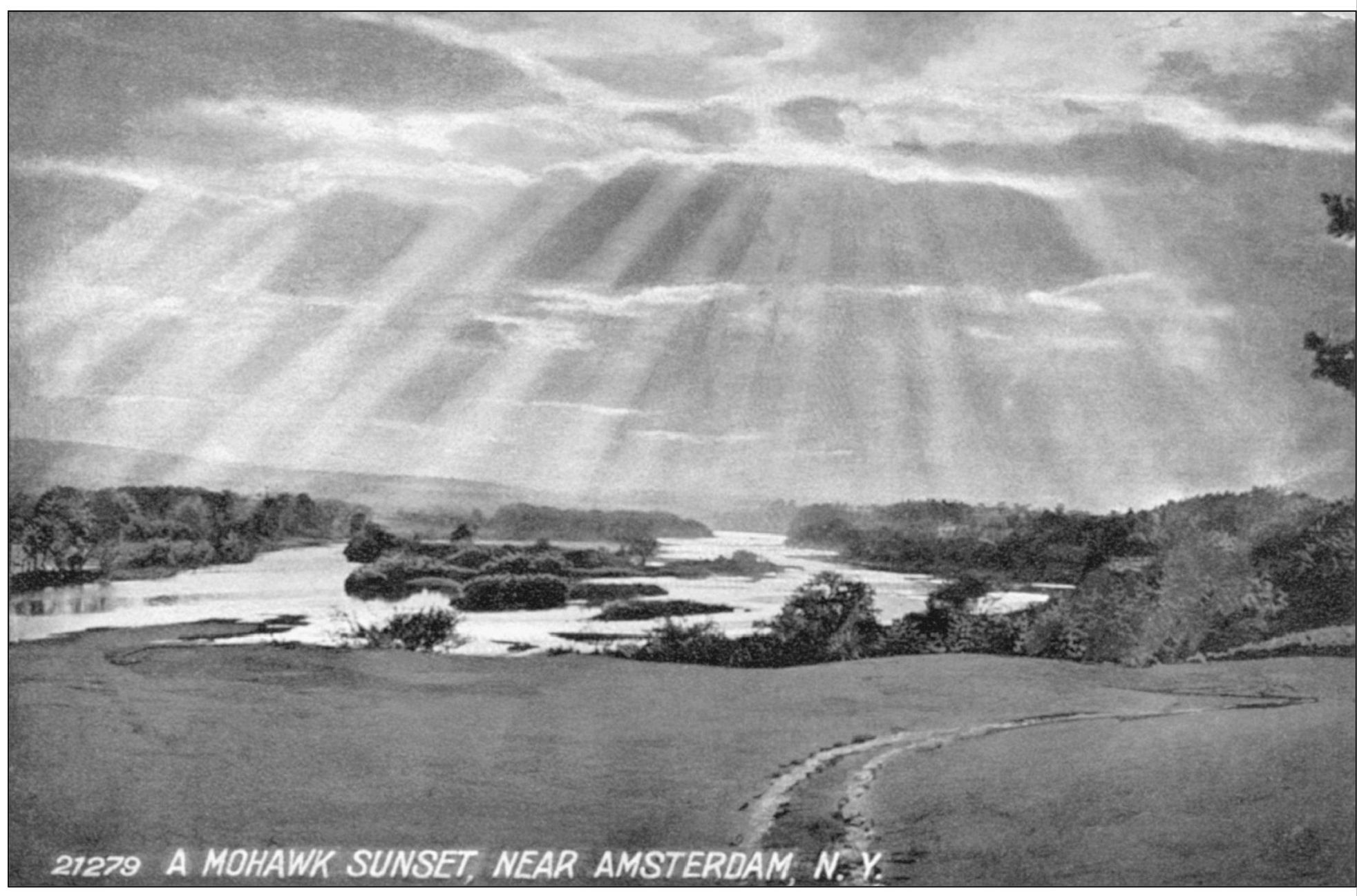

This card was chosen to be presented last because it best represents the continuing nature of Amsterdam history. As the postcard fad passed so eventually did the industrial heyday of the city. Now a new day awaits its dawning, and its outcome will depend on how Amsterdam capitalizes on the same forces—the land, the water, and the people—that made it great once before. (Courtesy of Rob von Hasseln.)