When I begin to list what’s wrong with the US healthcare system, almost every item on the list fits a single category: things we could do and should do but don’t do. Time after time, we possess the science, the resources, and the know-how to improve healthcare for Americans—but cannot seem to find the resolve or momentum to change.

Those of us who once could do very little for HIV/AIDS patients are keenly aware of how much we can do now. We’re like people who survived the Great Depression to live in a time of prosperity: We never forget how it felt to have nothing, and this memory colors how we value what we have now. And we’re not alone: Healthcare professionals dealing with a vast array of mental and physical ailments have more knowledge, more therapies, and more ability to heal than even a decade ago. Given this reality, it strikes me as inexcusable—a tragedy, really—that we fail to implement healthcare solutions that are within our reach.

Songwriter, children’s author, cartoonist, and poet Shel Silverstein has a name for such regretted missed opportunities: “woulda-coulda-shouldas.”

In the US healthcare system today, the woulda-coulda-shoulda atmosphere has become paralyzing. Each stakeholder argues for what should be done, making a high-flying case for its own self-interest. Each faction insists that something dire absolutely would befall the nation if their opponent’s approach wins out. So it’s a standoff and nothing gets done. Meanwhile, the politicking is so intense, and the smoke-and-mirrors so blinding, that the populace loses sight of what actually could be achieved if everyone pulled together: We could have appropriate, accessible, cost-effective healthcare across the board.

It’s certainly not just institutions that fall prey to woulda-coulda-shouldas. Individuals do too. Like me, chiding myself that I could have saved Clarence and Tommy if I had understood their liver issues sooner. Or like many HIV-positive patients who know they should take their medications, and who said they would take their medications, except … well, it’s complicated. Glenn Treisman can help me explain. He’s a psychiatrist who works with HIV/AIDS patients, a no-bull kind of guy, and a good friend.

While the HAART drugs we got in the late 1990s were effective against the virus, they often required dosing two or three times a day with multiple tablets. Not surprisingly, medications of that number and strength were associated with some wicked side effects. But the biology dictated that the drugs had to be taken precisely, consistently, every day, lest the missed doses allow the virus to replicate with some drug still present—a recipe for developing resistance.

When patients took the medicines every day, a significant majority—by 2004, perhaps three-fourths of them—achieved such suppression of the virus that it was undetectable in their bloodstream. Once patients get to that state, it’s almost as if they don’t have HIV anymore. As I would say to them, “It’s like you rounded up all the virus in your body and locked it in jail. Although it’s still there, it’s not in a place that can hurt you. But if you stop taking the drugs, JAIL BREAK! The virus will come roaring through and put you back on the path to AIDS.”

For all the sermons our patients heard about resistance, the presence of so many side effects led to folks skipping doses. When they needed a break from the nausea, the loose stools, and the abdominal pain, one missed dose led to relief—and that relief often outweighed their guilt at skipping the meds. After a while, the dose-skipping that had started as a desperate impulse became, for many patients, a habit, and one they were reluctant to confess to their providers—people like Glenn Treisman.

During more than two decades with the AIDS Psychiatry Service at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Glenn has gained great insights into HIV-positive patients’ behaviors. On the matter of skipping medication doses, he tells this story.

A physician and good friend of mine at Hopkins’s Moore Clinic for HIV Care, Dr. Joel Gallant, asked Glenn to talk to a patient who was an enigma. The patient claimed to never miss a dose of medicine, yet his viral load remained high. Joel would ask him on every visit, “Are you missing any doses of medicine?” “No,” replied the patient, “not a single dose.” Joel checked a drug resistance assay and found that the virus from the patient was wild-type virus, meaning there was no resistance present. Now Joel was totally stumped: The drugs should be working, he thought.

At Joel’s request, Glenn followed up, asking the same questions. Again the patient stated he had not missed a single dose. Glenn asked the patient when he had taken his most recent dose and the patient answered, “Earlier this morning.” So Glenn ordered a blood sample drawn, knowing that just a few hours after the drug was taken, it should be readily detectable in the patient’s blood.

The blood level results—no drug detected in the patient’s bloodstream—proved unequivocally that the patient had not taken the medicine as he had claimed. Glenn brought the patient back in and confronted him: “You told Dr. Gallant over and over that you had been taking your medicines every day without missing a dose, but the drug level indicates you haven’t taken your medicines at all. Why did you tell Dr. Gallant you were taking them?”

The patient looked up at Glenn, shrugged, and said sympathetically, “Because it seemed so important to him.”

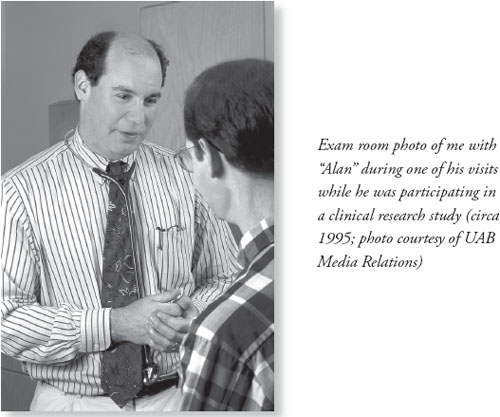

Mary Fisher and Cyndie Culpeper each struggled through several HAART regimens in the first years we had the new medications. At one time or another, each experienced almost every side effect the drugs had to offer: headaches, skin rash, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and neuropathy (numbness and/or pain) in their feet and legs. And periodically, each pleaded with me to approve of them taking a “drug holiday,” going off the medications for a while.

I can still hear Mary pressing me about it: “Mike, do I really need to take these medicines? I am doing so well. What would happen if I stopped?” To such questions from both Mary and Cyndie, my answer was the same: “The reason you are doing so well is because of the medicines you are taking—it’s not a good idea for you to stop.” But ultimately, a doctor (even when he’s a cousin or a friend) must respect a patient’s choices.

In late 1999, after more than eight years battling the virus, Mary decided the medications’ side effects were unbearable and stopped taking them. She felt better almost immediately, more able to care for her sons and keep up her speaking schedule. But she had given the virus an opening, which it took. In June 2001, Mary described her experience in an incredibly moving speech to a conference of AIDS doctors. The speech was titled “Passing Communities,” and in it she declared, “Community is still the driving need for us, for all of us—physicians and patients, researchers and reporters. Our only real hope is what Martin Luther King used to call ‘the beloved community.’” I was in the audience, fighting back tears as she spoke.

With Michael’s consent I went off most AIDS drugs more than a year ago. Then came the tests that said, in effect, that my body had gone into AIDS free-fall. Numbers we wanted to be low were skyrocketing and numbers we wanted to be high were tumbling. Michael wanted me back on drugs instantly. And I resisted. We talked about length of life. Then we talked about quality of life. And somehow we stumbled into the reality that Michael wants to keep me alive for ten more years because he’s convinced that, by then, he’ll hold a cure.

Three months ago in Birmingham, I was incredibly ill. Michael kept shifting the combination therapies to see if he could find one that I could survive. We both hung in there until Michael heard me say that I didn’t think I wanted to do this for another ten years … that I wasn’t going to do this for another year, let alone ten …

Michael has no clinical response to my hopelessness. At those moments he always resorts to the same thing. He says “I love you, and I do not want to lose you.” He uses the language not of the university lab but of the beloved community—and we start again, together, to find a glimmer of light.

In 2002, to Mary’s great relief and mine, we found a drug regimen that worked for her. With her success a matter of record, Mary’s experience gave me hope the next year when I went through much the same thing with Cyndie.

Cyndie had dropped her medications before. In December 1996, she told me in an email, “I’m following Nancy Reagan’s advice to ‘say no to drugs.’ I quit all of them. Can’t take the side effects anymore.” But her health grew increasingly precarious, and in January 1998, when she developed pneumocystis pneumonia, she agreed to get back on drugs. By 2003, Cyndie had settled into a three-drug regimen she could tolerate, and it was keeping her numbers where we wanted them. I was very pleased; Cyndie, not so much.

Cyndie may have lacked energy, but she never lacked gratitude. Cyndie was grateful that being on medication enabled her to teach young students at the Birmingham Jewish Day School, attend Shabbat services regularly, take her dog Annie Lucy for long walks, and travel. Cyndie loved to travel. After every trip, it became her standing joke to bring me a “barf bag” from the airplane (a little dig at me, I think, for prescribing such nauseating meds). She made a point of trying different airlines so she could scope out the different colors and styles of barf bags on each airline. Over the years, she enabled me to assemble an impressive collection.

Though the therapy was successful and occasionally she could joke about it, Cyndie was serious about wanting off the medications, which she called “the poison.” I wasn’t sure if there were some troublesome side effects she didn’t tell me about, if she was just tired of taking medicine every day—or if taking it reminded her too often about her HIV status. For whatever reason, she just wanted to stop taking her medicines once in a while. In late 2003, Cyndie notified me she was again taking a brief “drug holiday.”

On a Wednesday morning in January 2004, I received an urgent phone call from nurse Carol Linn at the 1917 Clinic. She said that Cyndie had been vomiting and was “very sick,” and that I needed to come immediately. When I got to the exam room, Cyndie was feverish and balled up in a fetal position, moaning. Asked what was wrong, she barely could croak out, “My kishkes” (Yiddish for intestines).

Cyndie’s abdomen was rigid and exquisitely painful, not just when touched but with any movement. As a former nurse, she was prepared for what I told her: This was an “acute abdomen,” most likely from a ruptured stomach, intestine, or appendix—and a surgical emergency. We called an ambulance to take Cyndie from the clinic to the UAB emergency room, and I met her there.

After X-rays confirmed the diagnosis, Cyndie was taken to the operating room where surgeons discovered a perforated cecum, the pouch at the beginning of the colon. An ulcer more than five and a half inches across had eroded through Cyndie’s colonic wall, leaking bowel contents into her abdominal cavity.

Surgeons successfully removed the diseased bowel and patched her up; she spent several weeks in the surgical intensive care unit, and then in a step-down unit. When she felt well enough to talk, I explained to Cyndie that in AIDS patients, such ulcers commonly are caused by a cytomegalovirus or a mycobacterium avium complex infection (as in Brian’s and Michael’s cases). But her pathology report revealed neither of these causes; the cause of the ulcer in her bowel wall was unknown. So in all honesty, I couldn’t tell her that stopping her ARV medicines led to the development of the ulcer. Even so, the episode convinced Cyndie to go back on her medicines and to stay on them.

Mary had started treatment with a higher CD4 count than Cyndie’s, and her virus in the test tube was much less aggressive than Cyndie’s virus. Nonetheless, I didn’t think either of them could afford the “drug holidays” they both craved, and I struggled to understand why they’d take the risk.

Glenn Treisman used his psychiatric expertise to lend me some perspective. As he reminded me, most of us will agree to try medicines we believe will do something good for us. But if the medicine makes us feel awful, after a while most will make a choice—to skip doses, or to continue despite our misery. The former choice is what Glenn calls “feeling oriented” and the latter “thinking or consequence oriented.” He explains:

Think of personality as a bell-shaped curve: on one extreme of the curve are those folks who are thinking, or consequence, oriented, and on the other extreme are those who are feeling oriented. A classic consequence-oriented person is your accountant. They don’t want to miss a single penny on the ledger, it drives them crazy. On the feeling-oriented end of the spectrum, think of Madonna or Brittany Spears or most folks in the performing arts, who act chiefly on emotion. Most of us are, by definition, somewhere in between. A good illustration is when we are in school and have a test tomorrow. Most of us don’t feel like studying, but the prospect of failure is so unacceptable that we study anyway. The thinking-driven student will stay up all night studying. The feeling-driven person will say, “Screw it, I don’t feel like studying, so I won’t. Maybe I’ll pass anyway!”

Glenn tells another story from his practice that helped me understand just how foreign the consequence-oriented approach can be to a feeling-oriented person. The story was about a patient whose cocaine addiction had once led him to tangle with, and get shot by, his drug dealer.

As Glenn tells it, the patient arrived requesting Valium, explaining, “I have been very nervous lately because I have been buying cocaine from the guy who shot me.”

Glenn asked, “Why do you buy cocaine from a guy who shot you?”

The patient replied, “Because he has cocaine.”

Perplexed, Glenn replied, “Look, I love prime rib, but if I went to the best prime rib restaurant in Baltimore and the maître d’ SHOT me, I wouldn’t go there anymore.”

Without hesitating the patient retorted, “You know what, doc, with an attitude like that, you’d be missing out on some good meat!”

Glenn’s conclusion: “The patient was not stupid; he processes data differently than I do.” Feeling oriented versus consequence oriented.

Rounding out the profile, Glenn explained that feeling-oriented individuals also tend to be focused on the “now” more than the future and to be motivated more by a hunger for rewards than by an aversion to consequences. This paradigm has helped me better understand how to approach the care of patients. But I can also see a broader use for it. I think we should consider which aspects of US healthcare policy generally are feeling driven, which are thinking driven, and whether the balance needs adjusting.

As I’ve told medical students who see me weep at losing a patient, I believe that conscientious healthcare providers are emotionally invested in their work—to an extent, feeling driven. And I believe that a world-class healthcare system must be run with heart as well as with reason.

That said, I also am a researcher, a lab rat who believes good data guides us in achieving good patient outcomes. I believe we should insist that healthcare interventions be judged by the quality of their outcomes. I believe those outcomes should be evaluated in a thoughtful way, through a process that is scientific, comprehensive, and objective. And I believe we should prioritize interventions that do pass—and drop interventions that don’t pass—three important tests of their outcomes:

This approach is basically what we’ve come to call “best practices”—taking measures of performance and then using them to devise procedures and standards that foster excellence. In the healthcare realm, it’s an approach that gets more lip service than serious implementation. I suspect that’s because if performance were rigorously measured, we’d find too many spots where the current system is neither health-effective nor cost-effective.

As I worked on this book, I sought out Glenn because he’s smart, compassionate, and doesn’t mince words. I asked him the central question: If the United States doesn’t have “the best healthcare system in the world,” why not? What needs to change to bring us closer to that goal? Even a portion of his longer, more thoughtful response points to the key problem:

If you’re an upper-middle-class person and you need a hip replacement, we’re the best health care system in the world. If you’re a guy on the assembly line in Detroit and you’re diagnosed with bladder cancer, we’re the best health care system in the world. But if you’re talking about the most bang for the buck, or the fairest system, or a system that does the best job of distributing resources, we suck.

The U.S. health care system is in terrible trouble and needs fixing. It is extremely idiosyncratic: If you don’t know the doctor and the doctor doesn’t know you, you might get great care or terrible care, there’s no way to predict. In the private systems of what’s called “managed care” medicine, the way they manage care is to deliver less of it and then they get to keep the money.

As the system operates now, the only way people can make a profit is by not providing care, by cutting corners on what they deliver. And that kind of system is doomed to fail, just as the auto industry and the steel industry failed when they took the same approach.

If Glenn could script the overhaul of the US healthcare system, he’d make it a government-run, single-payer system structured like those in Canada and England. In a system like that, he says, “the needs of the many could be met. The doctors and administrators of a clinic would get X dollars for that clinic and would decide how to spend it to cover caring for all their patients. If a patient needed some arcane kind of treatment, it would not be available to everybody at that clinic, but people would have the latitude to access additional care either by paying for extra insurance or by paying out of pocket.

“Critics of this approach say, ‘Oh no, that’s a two-tiered health system, you can’t do that!’ But right now in the United States we have a two-tiered, even a five-tiered system,” Glenn contends, because patients with more money and/or insurance can access almost any kind of care, and patients without money and/or insurance struggle to get even basic care.

Glenn figures that he spends about a third of his hours in the clinic “yelling at insurance companies who say they won’t pay for this or that. They’re trying to figure out, Can we get away with screwing this person so we can keep the money? Generally, I can get payment for almost any patient if I argue with the insurance companies enough—but it wastes my time. I’m penalized because I’m trying to get my patients good care.”

Glenn doesn’t get paid to advocate. So when he spends one third of his time advocating for his patients against a system in which people are paid to avoid approving pay for care of others, all that time is totally uncompensated. Like countless caring healthcare providers, he advocates because it is the right thing to do—because he cares.

If all the Good Samaritan healthcare providers stop contributing the unpaid services that are holding this dysfunctional system together, we’d see more chaos and collapse. So far, those of us who care continue to submit, knowingly, to abuse by the system. We let ourselves be used to fill the voids created by cut-corner policies and practices that generate tremendous profit for institutions and their shareholders. We do it because to stop would be to turn our backs on the patients. But to have to continue on this way … to quote my forefathers, “It’s a shanda!” A crying shame.

Glenn sees his psychiatric profiles at play in the decline of the US healthcare system. “The people who used to run the system were doctors who were future-oriented, thinking-oriented people,” he says. “Today, the people who administer US healthcare are business people and they are now oriented, feeling oriented. The more you let big-business people run it, the more you get a healthcare system that says, ‘Look, we can’t make any money on X, so let’s not do it.’”

And then we’re back where we started—faced with what we could do and maybe should do, but don’t do.

![]()

As our therapeutic options for fighting HIV grew, we could save more patients than I dared to imagine back in the 1980s. But even when we could beat back the virus, there were AIDS-related fights we could not win. Elliott’s was one.

Before Elliott got sick, he was an award-winning roller skater who prided himself on wearing outrageous costumes (kind of Evel Knievel-meets-Elvis). An Alabama native who studied at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Elliott was also an activist for what he believed in. His mother, Jean, tells of the Sunday morning her husband, Bill, “came in reading the front page story in the Birmingham News, saying, ‘Oh my gosh, Elliott is suing the University of Alabama!’ It seems Elliott and his gay friends were in one of the joints along the strip in Tuscaloosa when they started to be harassed by some rednecks. The gays were asked to leave and the troublemakers stayed. The next day found Elliott in the office of the president of the university, requesting that gays be given the same recognition as other groups on campus. That request went nowhere until he sued the university”—and after the university approved the establishment of an LGBT alliance, Elliott was a founding member and its first president.

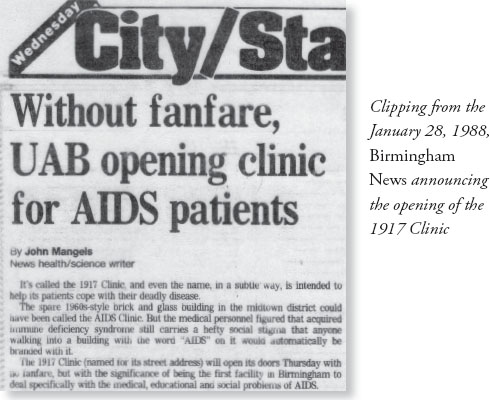

Elliott was just twenty-six years old when he first visited the 1917 Clinic within months after it opened. At that point he had fairly advanced HIV infection and was placed in an AZT study. From then on, Elliott proceeded to participate in almost every study we initiated at the clinic. He played the guinea pig with DDI, saquinavir, ritonavir, L–697,661—and probably others that I’m forgetting. He was dauntless. And to help others coming to the clinic, he organized and chaired a patient advisory board that provided information, counsel, and encouragement.

By 1996 Elliott was on a steady three-drug regimen (AZT/3TC/indinavir) that was keeping his HIV in check. But throughout most of the 1990s, he was fighting related illnesses, and those battles were taking their toll. He suffered one GI problem after another. The rectal cancer diagnosed in 1998 required chemotherapy and radiation that left him with enteritis (inflammation of the bowel). That made Elliott wary of going out lest he be unable to make it to the bathroom when needed, and that drastic restriction of his activities weighed heavily on him.

In summer 1999, Elliott was winning the battle against HIV: His viral load was consistently below 50 copies/ml and his CD4 count was 107. Then in August, he developed abdominal pain more severe than anything he had experienced, and we admitted him to the hospital. An X-ray revealed that there was “free air” in his abdomen, meaning his intestines had perforated somewhere. I consulted UAB surgeons who agreed Elliott needed an emergency operation.

With the surgical team standing by, I explained to Elliott what we needed to do. He answered me through teeth clenched in pain, and there was no mistaking the words or his conviction. “No more, Dr. Saag. I’ve had enough.”

My immediate reaction was to argue: “Elliott, no! This is fixable! We can get you through this. Your virus is totally undetectable, you’re controlling HIV—you’ve WON!” But from the look in his eyes, I knew the truth: He was done. So I held my tongue. In the past, he would have regarded this emergency as just one more battle to fight. Now, even in the grips of agonizing pain, he saw it as relief. Deliverance.

For several seconds, we sat in silence, searching each other’s eyes. Then I said, “I’ll be right back,” and went to give the surgeons Elliott’s decision.

The surgical resident said something offhanded like, “He’s probably right, he might not make it through surgery. We’ll sign off. Call us back if you need us.” Though I’m sure the words were well intended, I wanted to scream at the resident, “You don’t know who you’re talking about—this guy has fought through worse than this and made it!” But instead I thanked the resident and waved him on, so I could be alone to compose myself.

Giving up, when he had a condition we could remedy—that’s what I felt Elliott was doing, and it devastated me. How many other patients of mine would have given anything to be in that situation? Brian, Jacob, Jim, Ed, and so many more. We kept HIV from taking this guy’s life, and now he was giving it over. How could Elliott do this?

It took a few minutes before I realized that what I really meant was: How could Elliott do this to me? This wasn’t my professionalism talking. It was my grief, my sense of avoidable loss, my pain from watching all those other patients die of things they couldn’t avoid and I couldn’t fix.

Elliott had been through a lot, physically and emotionally. He had weathered too many illnesses. Felt too much pain. Lost too many friends. Suffered too much survivor guilt. The ruptured intestine had given him an out, and he was taking it with dignity and grace. Who was I to get in the way?

We started Elliott on opioids to dull the pain. His family gathered immediately: His parents Jean and Bill, sweet, loving people who had embraced Elliott unconditionally from the very beginning. His devoted older sister Pat, who to this day sends me birthday greetings via Facebook. I told them of Elliott’s condition and asked them to visit with him for a bit. When I returned ten minutes later, I spoke to Elliott for his family to hear. I told him his condition required an operation that he might not survive, but that it was much likelier that he would survive it and have a complete recovery from the episode.

Elliott smiled as he quietly confirmed his choice. “Thank you, Dr. Saag. Thank you. You’ve been great from day one, and I love you for everything you’ve done for me and my family. But my mind is made up. I’m ready to go. My family understands. I hope you do as well.”

I sat on the hospital bed with Elliott and gave him a big hug, then embraced his relatives as we all wiped away tears. “Visit with your family as long as you’d like,” I told Elliott, “and then we’ll increase your pain medicine to make sure you are not suffering.” He told me again that he loved me. I told him I loved him, too. And I waved good-bye.

Jean later told me that her son’s last words were quintessential Elliott, concerned about others and touched with good humor. “Momma, will you be all right?” he asked. “Please don’t cry and look like Tammy Faye Bakker …”

Of the many patients’ funerals I have attended, Elliott’s was one of the few where I gave a eulogy. I spoke of all Elliott had been through and all he had accomplished. I said that from day one until his last breath, Elliott did things his way. And I said that he was, in every sense, a winner. A champion, in roller-skating and in life.

![]()

About a decade into the HAART era, though there still were problems with the drugs, we had learned another critically important thing they could do. Once the medications suppressed a person’s HIV to undetectable levels in the blood, that person was highly unlikely to transmit the virus during sex, pregnancy, or childbirth. Indeed, such transmissions are so rare today they are considered “reportable.” We have less conclusive research data on whether people with “undetectable” HIV can spread the virus by sharing needles (transmission via the bloodstream). But we have almost 100 percent certainty that suppressing the virus to undetectable levels prevents sexual transmission and transmission from mother to child.

This was an enormous achievement. Before the medicines, there was a 25–30 percent chance of a baby acquiring HIV during pregnancy or during labor and delivery. Now, if we get women into prenatal care, identify those who are HIV-positive prior to the third trimester, and put them on medications that suppress viral replication to the point of undetectable virus in the bloodstream, there is no transmission to the baby. Just as for any HIV-positive person on medications that suppress the virus to undetectable levels, the likelihood of transmitting the virus to others via sexual activity approaches zero (perhaps not absolutely zero, but close to it).

Now, consider this: If we could identify all people infected with HIV, get all of them into care and on treatment, and have all of them achieve undetectable levels of virus in the bloodstream, three really good things could happen: People with HIV would live a near-normal lifespan, they would be spared illness caused by HIV—and they would be very unlikely to transmit the virus to other people. Theoretically, we could stop the epidemic.

There’s that word again: could. Because there’s a catch.

The drugs work best when started before the patient has more advanced disease. The mortality rate increases dramatically when therapy is started at lower CD4 counts than when it is started at higher levels. In our clinic, among those who start therapy with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/ul, mortality is 50 percent at eight years. Among those who start at counts greater than 200/ul, the mortality at eight years is less than 10 percent.

So for better outcomes, we need to get folks into care earlier—but the problem, is, most don’t show up for care until their CD4 count is less than 250 cells/ul. There is one group, however, that consistently presents with CD4 counts greater than 450 cells/ul. Who are they?

Pregnant women.

Why? Because since the late 1990s we have recommended routine testing of all pregnant women for HIV. (This is done through so-called “opt-out” testing, meaning the mom is offered the test as part of routine practice, but may opt out of having the test done. Very few moms refuse the test.) Once identified, a woman is referred for HIV care and started on treatment to prevent transmission of HIV to her baby and prevent progression of her own disease, an unquestioned a win-win situation.

I’m certain that if tomorrow I magically invented a conclusive “cancer test,” people would be lined up for miles to find out if they had cancer so they could be treated early and have a chance for long-term, meaningful survival. But for years we’ve had an HIV test—conclusive, noninvasive, inexpensive—that can tell people if they have the virus so they can be treated early and have the opportunity to live a near-normal life span. We don’t see any miles-long lines; we don’t see any lines at all.

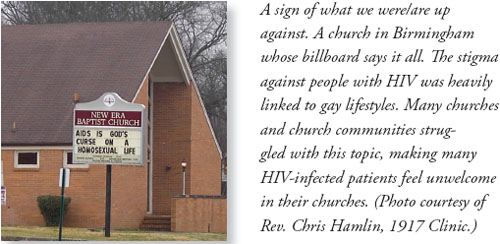

Why would people rush to be tested for cancer but avoid being tested for HIV? You already know the one-word answer: stigma.

As my cousin Mary Fisher, who’s had HIV for decades and was diagnosed with breast cancer months before she finished her 2012 book messenger, wrote: “If you have cancer in America, you look for a great doctor. If you have AIDS, you look for a place to hide.” That, as Mary rightly observes, is because “we’ve infused American AIDS with so much shame that women and men at risk are too afraid to be tested; they’d rather die than know. And once you are diagnosed positive, you head for silence, not support.”

For all the education campaigns and consciousness-raising during the past thirty years, HIV-positive people still face ostracism and condemnation. They are told they have HIV because they did something wrong, aberrant, unclean; that their disease is God’s will or God’s curse. This hateful treatment at the hands of their “community” makes them feel shame, and the shame keeps them from going to “that clinic” to get tested, lest someone see them. Add to the mix an unhealthy dose of denial, plus ignorance of how treatable HIV is if caught early, and you have a perfect storm of testing avoidance.

Since 2006, the CDC has recommended routine HIV testing for all individuals between the ages of sixteen and sixty-four. I don’t know how or why they came up with those ages, though it’s a good start. If it were up to me, I’d say that all patients followed in primary care settings should be tested for HIV. Those identified as HIV-positive should be referred immediately for care in an HIV treatment center.

We could do this—today, in all fifty states effectively—and yet we don’t do this. To me, this is the new tragedy of AIDS, a tragedy of missed opportunities.

As a result, patients show up in our emergency rooms with symptomatic HIV. Often they have had encounters with the health system in the months preceding their ER visit and no one ever considered the possibility of HIV. The patient “didn’t look like” they had HIV, or “had no risk factors.” The provider was in too much of a hurry to consider the possibility of HIV. So their diagnosis is delayed until they present with pneumocystis pneumonia, cryptococcal meningitis, or another of the telltale diseases of advanced HIV. And in those cases, even with all our miraculous new drugs, we all too frequently cannot save them.

This is a failure we could prevent, or at least mitigate, with two relatively simple actions.

The first would be to educate the public about the advances in managing HIV disease. We need to replace the old notion of HIV as a death sentence with the new medical reality: If people with HIV are treated early and appropriately, they can live a near-normal life span. Driving home this message will go a long way toward reducing the stigma that makes people fear disclosing their HIV status or even confirming it.

And that brings us to the second action we must take: aggressively implementing the policy of testing everyone for HIV, regardless of perceived risk. In this way, we would begin to make the test no more stigmatizing than other checks many people get during regular physical exams. And when we identify those who are positive before they experience advanced disease, they can reap the full benefits of modern therapy.

Gone are the days when we imagined the at-risk population could be circumscribed, as in the “4-H Syndrome” (for homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users, and Haitians) of the early1980s. Now that we know the virus crosses lines of age, gender, race, class, religion, sexual orientation, and more, how could we expect physicians to determine a given patient’s risk of HIV infection and thus who should or shouldn’t be tested? I often say that anyone who is sexually active, or even thinks about being sexually active, should be tested routinely for HIV. The testing is easy, quick, and accurate. Rapid oral tests can be administered in physicians’ offices and a result is available in twenty minutes.

This one-two punch, routine testing followed by linkage to care, is one of our best chances as a society to stop HIV transmission and, ultimately, eradicate the virus. If we’re interested in savings lives, here’s a way to do it. If we’re interested in saving money, here’s a way to do it.

In the United States today, it’s estimated that about 20–25 percent of people who are HIV-positive do not know it. Sadly, because they’re not on medications that would suppress the virus to nontransmissible levels, this 20–25 percent is responsible for more than 55 percent of the new HIV infections spread each year. By not knowing their status, they’re losing time getting into treatment that could save their lives—and they unwittingly pull others down with them. If we identified those folks earlier, got them into care, and initiated treatment, imagine how much benefit they and we could realize.

Could.

![]()

In the beginning, there was AZT. A few years later we got DDC and DDI—but that didn’t mean we had three approaches to treatment; it meant we had six when we used different drug combinations. And then once we had four drugs in play, we had as many as twenty-four combinations … and on and on, expanding exponentially. By the time we perceived triple-drug combinations as the best way to go, we had at least eight drugs we could administer by threes, creating hundreds of potentially therapeutic combinations with more on the way.

To track options and selected treatments, we needed a medical records system a little more robust than the database I had launched in 1988 on my home computer.

We were enrolling more and more people in care at the 1917 Clinic and in trials—and just for their care and treatment, there was so much we needed to track. Every one of them presented with a unique combination of factors, many of which had an impact on whether their HIV regimens were effective. There were medical issues: not just AIDS-related conditions but non-AIDS-related conditions ranging from diabetes and food allergies to drug and alcohol dependence. There were mental and emotional factors: depression, anxiety, family and marital upheaval, all of which could interfere with steady adherence to medical regimens and clinic visits. And there were social and economic factors—patients who drifted in and out of homelessness and joblessness, on and off insurance—that complicated treatment. To provide the most coherent, farsighted care, we needed to keep our arms around all those variables.

From the founding of the 1917 Clinic, we intended to use our database and repository to conduct research and then apply our findings to treatment. By the late 1990s, we saw just how dramatically we could scale up this process—how gathering high-quality data over a large range of patients would give us a remarkable, even unprecedented, capacity for research. And it was research that could inform best practices not just of care but of healthcare policy, a benefit that I hadn’t even imagined in 1987 when I dreamed up the clinic.

First, though, we needed the right tool. I could see it whole, in my mind, and it was a grand vision: a dream-machine system to collect, store, and draw findings from large amounts of patient and scientific data. A few electronic systems existed for that purpose, but the few built for research scientists weren’t user-friendly for care providers, and the many built for care providers focused on billing and appointments and weren’t adequate for researchers. The right tool for both jobs would have to be custom designed and custom built.

A streak of luck (or magic) brought me just the right people to make that happen—one of whom was Flohoney Switow’s daughter. Especially since I had been involved in Mary Fisher’s care, her parents, Marjorie Switow Fisher and Max Fisher, had been interested in my work at UAB. Max was a brilliant entrepreneur who had grown a tiny oil reprocessing business into the largest independent oil company in the Midwest. He was a regular on the Fortune magazine list of the world’s wealthy, a Republican Party power player, and, with Marjorie, a great benefactor of Detroit, the state of Israel, and other causes.

In March 1999, I went to Max and Marjorie’s winter home in Palm Beach, Florida, to seek support for a project to develop an electronic medical records system from scratch. I was perhaps four minutes into my spiel when Max interrupted me to ask, “How old are you?” Taken aback by the abrupt question, I responded, “Forty-three.” “Hmmm. Young man,” replied the ninety-one-year-old. I realized Max was already several steps ahead of me: Assuming that it would be successful, he wanted to be sure I had enough career time to convert this to a business. To him and Marjorie, this was the best gift they could give to me. As the conversation continued, it was clear both Max and Marjorie understood what this project could achieve; they “got it.”

In 1999, the Fisher Foundation made the initial grant to develop the UAB Electronic Medical Records (EMR) Database Project. I’ve never forgotten my great-uncle Sam declaring that only SOBs thrived in business, and I still didn’t think I was an SOB. But if Max Fisher thought I had enough business smarts to lead this new product development project, I was not going to argue.

We immediately began building an EMR from scratch. We started with a systems analysis to assess the origin of every data element we needed to include in the EMR, who entered the information, who used it, and in what form. The analysis took more than two and a half years to complete—but it was worth the time because with the groundwork laid by the systems analysis, the programming was much easier and much faster.

In August 2004, we launched an EMR system that was groundbreaking. Patient information could be entered simply, in formats personal enough for doctors’ use yet uniform enough for research analysis. If a clinician tried to order a medication that might interact with a patient’s other prescriptions, an alert popped up on the EMR screen. And perhaps most importantly, the providers loved working with it.

That year, the team got a new member: Dr. James Willig. Because he brought both a medical degree and computer expertise from his native Dominican Republic, he could understand the features physicians and researchers needed in the EMR, then help our technologists build them. One of the first questions James asked me was a stunner: “How do you know data in the EMR are accurate?”

Incredulous, I answered, “Because they are entered directly by the providers—no middle man. The data are coming directly from the medical encounter.”

James listened, thought for a moment, and asked, “Do you mind if I do an experiment?”

Over the next six months, James dug into the data that had been entered in the EMR. He carefully compared the information that the providers had entered in two places. The first was the problem list and medication profile, the data fields that were discrete and analyzable, the essence of what we use for research. The second was the free text comments at the end of the encounter note—in essence, what the provider was truly thinking at the time of the encounter. His results were shocking: In fields where medication data was recorded, accuracy was only 73 percent. In the problem list fields that concerned diagnosis, accuracy was only 53 percent.

What James obviously had suspected was borne out: Our EMR had a serious accuracy gap. We played the findings back to the providers and their performance improved in entering data. But James’s point was made: We needed to continuously reconcile the provider’s intent with the discrete, analyzable data elements in the EMR. Under James’s leadership, the quality-control software was backed up by a medical team that reviewed every piece of EMR data within seventy-two hours after it was entered, flagging discrepancies, correcting errors—a 100-percent, 24/7 data reconciling process that produced one of the most error-free bodies of HIV/AIDS patient data in the world.

In 2007, UAB was notified that our EMR had earned an Excellence in Information Integrity Award, an international honor for achievement in information technology. Out of seventy nominees in the not-for-profit category worldwide, we won first place—an honor that James and I were proud to accept at the award ceremony in Chicago.

In medical school, James had imagined a career of hands-on patient care. With the EMR, a much bigger world opened up in front of him. He described it to me in an equation, xyz, exponentially expanding. “Say x is the amount of patients we can care for directly at UAB. When we publish research findings from the EMR, you expand the impact by y, all the scientists and physicians who can do their jobs better because of that knowledge. Then you increase that to the z power, all the patients around the world whose care will be improved because of what has been learned and shared.” And the gains would keep redoubling, as we incorporated EMR users’ feedback to make the system work even better.

At which point, we welcomed “Mugs.” Mugs is the affectionate nickname of our beloved team member Dr. Michael Mugavero, who’s played a key research role for both the 1917 Clinic and the UAB CFAR. A Long Island native, Mugs came to UAB as an internal medicine resident, fresh out of Vanderbilt University Medical School and inspired by his work at a Nashville AIDS clinic. He later joined the UAB faculty, where he found that the research gains made possible by the EMR were “dramatic.” While other institutions might spend months doing studies with older and incomplete information, the EMR gave UAB researchers what Mugs called “100-percent quality-controlled, real-time data” as fresh as the weekly computer run. That capacity vaulted us ahead in developing scientific knowledge and in publishing what we learned in the world’s top medical journals.

The strengths of the EMR helped Mugs—who went on to be leader of the UAB 1917 Clinic Cohort, director of the UAB CFAR Clinical Core, and ultimately codirector of the CFAR overall—win a five-year NIH grant to study HIV/AIDS care access issues. The EMR helped UAB secure a lead position among eight US universities merging their AIDS research data in a $2.45 million NIH project called CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. And with EMR data, we documented how the consistent use of ARV drugs dramatically reduced healthcare expenditures by keeping HIV patients healthier overall—findings that were published in an ID journal and shared on NPR’s All Things Considered program where I was interviewed by host Michelle Norris.

In 1999 we wanted the EMR system because it would advance patient care and research capacity. In the years since then, EMRs and related tools—known collectively as Health Information Technology (HIT)—have been identified as a key element in curbing healthcare costs. A research report by the nonprofit Rand Corporation concluded that “Properly implemented and widely adopted, [HIT] would save money and significantly improve healthcare quality. Annual savings from efficiency alone could be $77 billion or more. Health and safety benefits could double the savings while reducing illness and prolonging life.” The Rand report projected that the savings from HIT would be vastly greater than the costs: “Implementation would cost around $8 billion per year, assuming adoption by 90 percent of hospitals and doctors’ offices over 15 years.” Since Rand produced those estimates in 2005, the cost of implementation undoubtedly has increased, but I’m sure the savings we could reap have increased even more.

There’s no silver-bullet solution to all of what’s broken in the US healthcare system. But I know, based on my own experiences, that HIT has enormous potential for improvements in quality and cost-efficiency in healthcare. With just our relatively small system at UAB, we were able to guide treatment and enhance quality of care significantly, in real time. With knowledge developed from our data, we became much more proficient at saving lives and saving money. And if an EMR system could handle a hydra-headed monster of a disease like HIV/AIDS, it certainly could prove useful in other medical fields.

As usual, Max and Marjorie Fisher knew a good idea when they saw it.

![]()

I traveled to Zambia again in 2001, the year that Drs. Jeff and Elizabeth Stringer and their two young children moved there full time to lead the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ). As a nongovernmental organization working in partnership with the Zambian government and UAB, CIDRZ set up research facilities in government-sponsored clinics that delivered primary care. By colocating, CIDRZ practitioners could swiftly adapt treatment based on what their research revealed, helping immediately to stem the HIV epidemic that infected an estimated one in six Zambians.

Jeff and Elizabeth, both gynecologists, focused intensely on developing therapies for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT for short). Their challenge was to find PMTCT approaches that were feasible and affordable even in such a resource-poor setting. And our ongoing challenge back at UAB was to help them roll up as much additional funding as possible so their work could continue and expand.

I distinctly remember a conversation with the Stringers in fall 2003. Elizabeth was eight months pregnant with their third child, and they had returned to the United States for the birth. Jeff said they had heard of a possible new source of funding, but he would need UAB’s help to position CIDRZ to compete for it. “It’s this thing called PEPFAR,” Jeff said—an odd-sounding acronym that at that moment meant little to me. But since then, of course, PEPFAR—the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief—has become one of the best-known and most widely hailed global health initiatives ever.

Zambia was named one of PEPFAR’s first fifteen “focus countries,” and CIDRZ was one of the early grantees. In March 2004 I went to Lusaka with several UAB 1917 Clinic staff, including Jim Raper, to help CIDRZ set up its PEPFAR-funded programs. At our first organizational meeting after arriving, I remember thinking about what I knew of federally funded programs and cutting to the chase. As I opened our meeting I said, “It’s great that the US government is giving this amount of money to support treatment here in Zambia. But in two or three years, Congress is going to call us in and ask us, ‘What did you do with all that money?’ We need to be able to respond with data, not emotion. We need to know precisely how many patients have been treated and what their outcomes were.”

Echoing what we had done Alabama with the 1917 Clinic, we set up the CIDRZ PEPFAR-funded treatment program to enroll patients as rapidly as possible and to serve them as comprehensively as possible. Alongside the treatment facilities, we set up labs and computers so the staff could study and document every patient outcome, logging results both for CIDRZ research and for accountability to its funder, the US government.

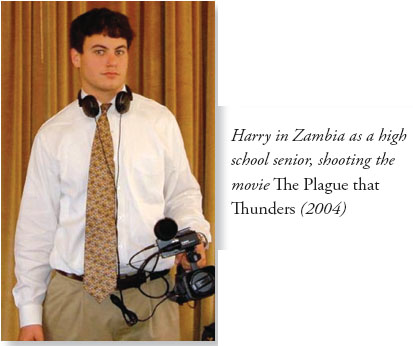

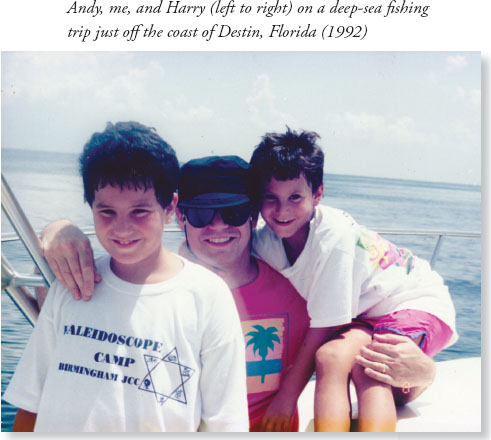

If the PEPFAR start-up wasn’t exciting enough, this trip had another bonus: My son Harry, then eighteen and a high school senior, took time off school to go on the trip with me. The principal of Harry’s high school, Dicky Barlow, had agreed that Harry could do a special project on AIDS in Africa. I suggested that the project’s “term paper” be a documentary video, and Principal Barlow agreed, on the condition that Harry would show the documentary to the entire school at an assembly upon our return. I said, “No problem.”

Because this was Harry’s first visit to Africa, and his first experience of HIV/AIDS in the developing world, he saw everything with fresh eyes. Here’s how he would later recall it:

I knew the basics about Africa and had watched documentaries, but there is no movie or picture that can do justice to what it really is like when you’re there. Nothing could have prepared me for the way the people live—which is, obviously, how people live in a large part of the world but so different from how we live in the United States.

The other thing that struck me was how different the AIDS epidemic was in Zambia and in the United States, like night and day. By 2004, HIV had become more of a controlled phenomenon in the United States—but in Africa, it might as well have been 1980 in terms of the lack of control, the unmitigated spread, and the death rate.

I’ve always thought my dad had a lot of foresight. In Africa, it was amazing to watch him and his colleagues basically build out an entire HIV care machine—to identify how to allocate funds, how to build alliances with the government and other groups, how to set things up from the pharmacy side to the doctor side to the lab side, and how to get people into care.

While in Zambia, Harry and I shot twenty-seven hours of video. When we got back to Alabama, we spent hours editing it into a twenty-four-minute production he could show at the high school. On the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe, we had photographed the breathtaking Victoria Falls. In Swahili it is called Mosi-ao-Tunya—“The Smoke that Thunders”—because the waterfalls create smoke-like clouds of mist and a thundering roar that’s heard for miles. Playing off that name, we gave the documentary the title AIDS in Africa: The Plague that Thunders.

After Harry showed the video to the school assembly, there was a short discussion period. Harry answered his classmates’ questions about the experience—and then I asked the final question. “Since we got back, all of the parents have asked me, ‘Did this trip change Harry at all?’ Well, did it?” I asked.

Without hesitation, Harry said, “Yes, it did.” And then turning to the audience, his peers, he continued: “We think we have problems here. We don’t get the car we want. We don’t get the date we want to the prom, or get into our first choice of college. Now I know, we don’t have problems. They do.” The audience responded with a standing ovation.

With support from PEPFAR, UAB, and others, CIDRZ began to turn the tide of HIV/AIDS in Zambia. Its antiretroviral therapy (ART) program enrolled more than 53,000 children and adults in long-term HIV/AIDS care by the end of 2006, treating 33,000 in the first twenty-four months. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention official hailed CIDRZ’s ART program as number one among those PEPFAR funded. And CIDRZ’s PMTCT program expanded to serve hundreds of thousands of women and infants at dozens of sites across Zambia.

As CIDRZ’s reach grew, Lusaka’s mortality rate dropped, falling by more than half in just a few years. When I returned to the United States from a 2008 trip to Zambia, I was delighted to tell Harry of my conversation with Medicine, the improbably named gentleman employed as a driver for CIDRZ.

As he was driving me across town late one morning, I said, “Medicine, I know you are proud to work for CIDRZ and you can see how the programs are helping, but does the average person on the street see a difference?”

His response was instant: “Oh, yes. Just look at us.”

I didn’t understand: “What do you mean, Medicine?”

“Look at us! Right now. We are moving. No traffic jams.”

“I don’t get it, Medicine. What was the cause of the traffic jams?”

“Funerals.”

No gridlock; no delays. No more coming to a halt so a funeral procession—or two, or three, or a dozen—could pass through the city to the cemetery. Before, the daily deaths from AIDS resulted in all those funerals and all those traffic jams. Now, traffic moved freely. And the people of Lusaka could see the difference—a visible victory of the health system in Zambia over the thundering plague.

I’ve been hard on presidents. But the PEPFAR program that President George W. Bush initiated was rightly hailed as “a lifeline” in a congressionally mandated Institute of Medicine (IOM) evaluation released in early 2013. As I write this, PEPFAR has funneled more than $44 billion to more than 100 countries. The IOM report says that PEPFAR “has achieved—and in some cases surpassed—its initial ambitious aims. These efforts have saved and improved the lives of millions of people around the world.”

From the beginning, PEPFAR required countries to have created a national AIDS strategy in order to be eligible for those US aid dollars. Makes sense, right? And yet, the United States itself did not devise such a strategy until some six years after the launch of PEPFAR—and two years after President Bush left the White House.

The good news is, when the Obama administration unveiled the National AIDS Strategy in 2010, it set the right priorities. It emphasized universal testing, linking newly diagnosed people to care, and then retaining them in care.

It’s great that US leaders have gone to bat against HIV with PEPFAR—but while looking to Biafra, they sometimes lost sight of Birmingham. And it’s fine for presidents to unveil strategies and lawmakers to make speeches and think tanks to release reports. But when AIDS was ravaging Lusaka a decade ago, what cleared the funeral traffic jams was testing, care, and treatment, offered as quickly and broadly as humanly possible. Just that simple.

I don’t mean to sound ungrateful. I mean no disrespect when I say this. But when it comes to mounting a response to HIV/AIDS at home as well as abroad, and it when it comes to dealing with the health of our people as well as of our economy, it’s painfully clear: America really could do vastly, vastly better.

Could.