Severe weather events will become more commonplace.

SETTING THE SCENE |

1 |

MUCH HAS BEEN ALREADY WRITTEN about our changing world and this book does not delve into the causes, the facts or the solutions for climate change, peak oil and food sovereignty.

These are the “big three” that are taking center stage at this point in history, and for those of you who are not aware of some aspects, here is a short summary of each.

People often focus on one problem, so you find groups solely focusing on peak oil or climate change, or some other ecological problem. We really need to broaden our thinking in a more holistic way, because when you consider human existence on this planet, I believe that the most pressing issues are food sovereignty (some suggest food security), peak oil and then climate change, in that order, although this order is debatable.

While change is all around us, it is our response that is most important. As we all move through this period of transition, we will need to re-skill and adapt, find new ways to solve new problems, and amongst all of this, enjoy our lives and our families.

When we first learned about our Earth heating up a few decades ago the focus was on “global warming.” There was contention, as there still is today, about whether global warming is caused by humans, enhanced by humans or just a part of nature’s cycles — as historical evidence has shown cycles of ice ages and warmer climates in the past.

As science and observational data developed in recent years, it became more apparent that the focus was about “climate change,” the predictions of severe weather events and extremes, changing rainfall patterns and changing temperatures. While a few skeptics still believe humans haven’t really had any effect on our climate, it is commonly held that we have increased the rate at which Earth changes are occurring.

Severe weather events will become more commonplace.

From a permaculture perspective, this is a real concern and we need to respond to this in a positive way. We need to grow food plants that are resilient to local change and to develop techniques for an integrated pest management strategy, as the cycles of pests and predators also change with the seasons and some of these are “out of kilter” with each other.

Coupled with our changing weather patterns are increasing levels of pollutants in our atmosphere. We are still pumping tons of carbon gases into the air every day, and this is overlooked by governments and industry, who both seem complacent about the destruction we are doing to the planet.

Fossil fuels are being rapidly consumed, and the gases produced from burning contribute to global warming.

It would be true to say that some governments exhibit deliberate inaction, and this would only make the impact of climate change worse.

» DID YOU KNOW?

If you want to know more about what this means for our future, make a search online for transition towns, peak oil, 100 mile diet, post carbon cities and the relocalization network.

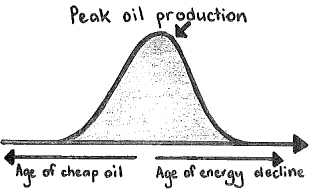

Oil resources are finite — we will eventually run out. We have so far used about half of the known reserves in the world (some scientists suggest more than half), but as more oil is pumped from the ground, what is left gets progressively harder and more costly to access. Fuel prices rise and the cost of synthetic chemicals (both fertilizers and pesticides) increases dramatically as the price of oil increases. This has implications for the cost of food.

Peak oil has occurred. We are heading towards the age of energy decline.

Like climate change, large numbers of books and articles have been written about the effect of peak oil on human existence. Our modern society is totally dependent on oil, that relatively cheap fossil fuel that drives the economy, fuels machinery and transport systems, and is used to manufacture a large number of products.

While we still have enough oil and gas and coal to last decades, we need to develop energy alternatives.

Many writers refer to this period of energy decline as a time when we could wean ourselves off oil and develop longer-lasting energy sources, such as wind, solar and water.

Bicycle use throughout the world has increased in recent years.

» DID YOU KNOW?

The concept of peak oil was put forward by Marion King Hubbert in the mid-1950s. He predicted that we would rapidly use the world’s vast oil reserves and that the rate of extraction would “peak” when half of the reserves were consumed. We appear to be at the halfway mark, and now we are heading down the slope.

As oil is depleted, goods and products will increase in cost. You might be surprised to find out just how many things we have in our homes that use oil in their manufacture. There will be issues around transport and food production, the cost of goods and services, and production of electricity and heating in our future.

I would like to think that the impact of peak oil can be offset to some extent by new and improved technologies and by changes in the behavior of individuals.

First we need to distinguish between food sovereignty and food security. Food sovereignty is about our control over the food we eat. This means that as we are the growers and consumers of food, we should take more responsibility and be more involved in the policies of food production and its distribution, rather than the large corporations that currently dominate the global food system.

Food sovereignty is about the rights of people to make their own decisions regarding the way they farm and what they grow, and this enables greater choices for consumers.

Food security is about the supply of food: year-round access to sufficient food that is safe and nutritious and can support an active life. It is both about quality and quantity. Food security has four components: availability, access, use and stability.

Food availability relates to production and distribution: how much food can be grown and how it can be moved to other areas. A country doesn’t necessarily have to grow food in order to achieve food security, but most countries endeavor to promote agricultural enterprises.

Access to food refers to the ability (or inability) to obtain food. Poverty can limit access to food, so income is strongly correlated with the purchase and allocation of food.

Food use refers to the efficiencies of individuals in metabolizing food, so both the food quantity and quality are important. People need to eat safe foods and to make sure their dietary requirements are met.

The fourth component of food security, stability, is about our vulnerability in regularly obtaining adequate food. It is a reflection of the previous three components (availability, access and use) over time.

As we are losing more arable land each day, and as the world’s population keeps growing, eventually there won’t be enough food for everyone. This becomes even more severe as our climate changes (and so plant cycles change, and drought or fire may seriously affect some food bowl areas) and the cost of operating machinery (costs of production and fuel) escalates.

No amount of science, genetic engineering, cloning or advances in agricultural techniques and methods will provide the shortfall.

Many people believe that to grow more food on the scale required will ultimately mean the increased use of pesticides and herbicides to control the pests that are just as keen to eat our food as we are.

Furthermore, half of every ton of fertilizer applied to fields never makes it into the plant tissue. It ends up evaporating or being washed into local watercourses or leached through the soil.

» DID YOU KNOW?

In Australia 440 different pesticides are routinely used, and in 40 years of intense pesticide use we have not eradicated a single pest.

This madness must stop. If we are to have a future, we need to grow our food organically. We need to embrace the concept of food sovereignty and work towards more recognition and support for our farmers and growers. But we also need to address the issue of overpopulation. There just won’t be enough resources for everyone, and while governments and countries recognize this problem, few seem to be doing anything about it. Some countries have brought in measures to curb population growth and they have been looking afar to ensure they secure resources to meet their growing needs. Governments move forward in an exceptionally slow way. Any changes that occur will happen at the grassroots level, and this is why the Transition initiative and other similar endeavors have been so successful to date.

Food sovereignty is about controlling where your food comes from and what types of foods you want to consume.

The issues surrounding food sovereignty and food security are complex because they involve international trade and economic development, and impact directly on our health and wellbeing.

We need to learn how to better use foods.

Some people suggest that there is enough food in the world to feed everyone adequately; the problem is distribution. Others contend that we need to develop strategies for resilience because we just don’t know what our food production capacity will be in years to come. We need to learn how to make better choices when buying food and make better use of leftovers and thus reduce food waste.

Permaculture promotes home food production.

Historically, permaculture focused on redesigning our agricultural systems and reintroducing food production into the household economy. This led to excess produce being stored and, in turn, greater food security.

We believed that food security was storing enough away for tougher and lean times, when particular seasonal foods were not available. And while we still hold onto those beliefs, we also need to see the bigger picture.

The challenge we need to set ourselves is:

• How can we strengthen and expand our current farming sector, as many industrialized countries are experiencing declines in their annual food production?

• How can we support the agricultural sector of our community to produce safer foods?

• How can we make farming a more resilient enterprise because, as we have seen so often, it only takes a severe drought or extensive floods to seriously cripple a country’s food production?

These questions are clearly about food sovereignty as they involve economics, markets, policy, politics and people.

The power of community revolves around food. Food is what brings people together.

People get and understand food much more easily than water and energy efficiency, so it is easier to bring people together to discuss growing food. That is where permaculture comes in.