Oak produces acorns during the autumn feed gap.

FODDER AND FORAGE SHRUBS AND TREES FOR FARM ANIMALS |

9 |

MANY TYPES OF PLANTS are used to feed animals. Grain crops (oats, sorghum, millet, corn) and a whole host of grasses are the most commonly used fodder worldwide. This section mainly deals with the larger shrubs and trees.

In the US and Canada and most other countries there are several climatic zones, typically based on rainfall. So there could be areas classified as dry temperate, wet temperate, subtropical, monsoonal and alpine, for example, and as different plants tend to grow in different areas, it is not possible to always obtain, grow and nurture every tree and shrub mentioned here. Do some research and select the plants most suited to your soil and climatic region.

For simplicity I have divided these plants into three groups: those that survive in dry climates (arid, desert, low rainfall areas), those that prefer cold climates (temperate and Mediterranean) and those that tend to thrive in warmer climates (subtropical and tropical). Species are listed alphabetically by common name.

In North America there are 11 recognized climate zones, with unique flora in each zone, so trying to place particular plants into one of three zones is not ideal.

» DID YOU KNOW?

The terms fodder and forage are often interchangeable. However, some texts suggest that fodder is what is given to animals (cut and carried) while forage is what they source themselves. The following sections just talk about fodder as meaning both fodder and forage.

Fodder from trees and shrubs is especially useful during drier periods and the autumn feed gap when nutritious food is not always available. Fodder plants should not be seen as just providing food during shortfalls, but also as positively contributing to an animal’s growth and weight gain.

Providing appropriate fodder on the farm negates the need to buy grains or food during these shortage periods and to compensate when adverse weather or other conditions minimize pasture production.

Ideally fodder plants should:

• be long-lived, perennial plants

• be reasonably drought tolerant (extensive root systems)

• be waterlogging and salt tolerant

• have the ability to be severely pruned or coppiced and then recover

• have high productivity of edible material (many tons per hectare)

• provide high quality nutrient-dense food

• be cheap and easy to establish, grow and harvest

• have fast growth rates

• be multifunctional (fire retardant, N-fixing, windbreak, useful shade, timber)

• provide leaves, pods or seeds in summer and autumn

• have high digestibility (easily broken down by the animal’s digestive system so that nutrients become available)

• be highly palatable (pleasant to eat)

• contain no toxic parts

• not inhibit nearby plants and pastures (allelopathic relationships).

Unfortunately, many fodder species are short lived and do not have all of these characteristics, so it is difficult to find the perfect plants.

From a permaculture perspective we also look for plants that reduce wind and soil erosion, require minimal water use to maintain their growth, improve soil structure, increase the biodiversity of the farm and do not themselves become environmental weeds. The ways in which pasture and fodder plants are accessed by animals is mainly discussed in chapter 11.

Animals are selective eaters. They will eat saltbush and tree medic, for example, but if other herbaceous (grassy) plants are available these are preferred.

Young trees can contain too much sap, harmful chemicals and other organic substances that deter browsing, so mature trees and shrubs are more often eaten.

On the other hand, other types of young plants are often vulnerable to browsing and the whole plant can be killed. Whereas grasses can recover quickly if stock are moved on, trees and shrubs need more observation and management as greater damage can be done by overgrazing. Also, a particular forage may have low palatability in the wet season but become desirable in the dry period (or vice versa). So there are many factors and intricacies between plants and their consumers.

I also need to stress that some of the plants discussed here may be declared (and prohibited) weeds in your region. Furthermore, seed and plant material may not be available where you live.

You can substitute any of these for others that are more appropriate to your soils, climates and animal types (but do remember to check their environmental status).

Animals, like humans, cannot live on one food type alone. The plants discussed here should be seen as just one part of a varied diet.

The foods that are normally consumed are often seasonal, and many of the fodder species are useful additions or supplements to seasonal feed shortages, and as an alternative food source when adverse conditions or disasters occur.

Again, don’t rely on one main fodder species but a combination of several different trees and shrubs along with pasture is more likely to provide a good balance of protein, energy, carbohydrates and good nutrition.

Mixtures of fodder plants have production increases of about 1 t/ac/yr for every 1.5 inch increase in rainfall. As grasses dry out digestibility decreases. This is because dry grass is high in cellulose and lignin (fiber) and low in carbohydrate and protein. Stock can then move onto other fodder species.

Animals that eat plants (fodder, forage) are herbivores. They have specialized stomachs and digestive systems to break down cellulose and other tough plant components.

Animals that mow grass and other plants close to the ground (grasslands, pasture) are called “grazers,” while those that chew on leaves, stems, fruits and woody twigs of the larger shrubs and trees are termed “browsers.”

Many grazing animals can be seasonal browsers. Sheep may nibble on pasture grass most of the time, but if the grasses start to dry out and shrubs and trees are present, they will eat the leaves and branches as well.

Oak produces acorns during the autumn feed gap.

This is typical of most animals — if their preferred food is not available they will eat something else. Most grazers will also browse and even ringbark trees if their diet lacks certain minerals.

Common farm animals that graze on low-lying plants include sheep, geese, rabbits, horses, donkeys and cattle. Farm animals that are browsers include goats and deer. Non-farm animals such as giraffes and camels also fit into this category.

Browsing animals can have an advantage over grazers when grasses die off, as they can turn their attention to woody plants.

Grazers have an advantage as there is often more nutrition in the young, rapidly growing grasses than in old mature shrubs and trees, which tend to be very woody.

Even though grazers and browsers have their own niche in the ecosystem, both groups of animals can interchange their roles to some degree.

If farmers can’t provide enough food, they may need to de-stock during lean times (either sell or agist elsewhere) or store hay and silage for later use. Fodder trees and shrubs should be seen as important supplements to pasture grazing.

Saltbush (like some other fodder species) may change its palatability from one soil type to another.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Sheep, goats and cows are ruminant animals, and they are foregut fermenters. They have four chambers in their stomach, which allows them to fully digest fibrous plant material. They can regurgitate their food, re-chew their “cud,” then re-swallow and finally continue with the digestion process.

Horses and rabbits, on the other hand, are hindgut fermenters. They have an enlarged cecum, an offshoot of the large intestine, which permits them to digest tough plant material.

A third group of animals called pseudoruminants (alpacas, llamas and camels) have a three-chamber stomach to help them slowly ferment and digest food. They are modified ruminants as they do regurgitate and chew their cud for many hours each day.

The following plants can survive in areas with an annual rainfall of less than 24 in. In some cases they are quite productive, but others only just survive. The growth habits and productivity of most plants respond to water, and to a lesser extent soil type. These same plants may be much more productive in higher rainfall areas, and possibly not so productive in clayey soils when compared to growing in sandy loams, but each species does have a preferred range of conditions in which it will grow.

Carob is a drought-hardy tree.

Table 9.1. Generic fodder plants for dryland areas.

Cool climates have rainfall between 24 and 40 in, and include wet and dry temperate and Mediterranean climate zones.

There are many plant species that are used as fodder for animals. Some plants are specific for particular animals and some plants are eaten by many different types of animals. Here are a few generic fodder plants.

Table 9.2. Generic fodder plants for cool areas.

Typically this includes plants that thrive in annual rainfalls over 36 inches in the subtropical, monsoon and tropical zones.

Some plants may not be suitable for your area. Mesquite, for example, is a declared (prohibited) plant in most states of Australia, but it is a remarkable multifunctional tree.

Coprosma produces succulent leaves.

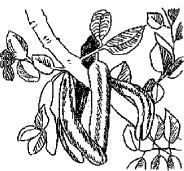

Honey locust pods contain high levels of sugars.

Acacia saligna leaves contain 15% protein.

Tree medic is a nitrogen-fixing shrub.

Pigeon pea provides food for both humans and animals.