THE MOST PROMINENT French collaborator with the Nazis would be none other than former Prime Minister Pierre Laval, who had decreed firearm registration in 1935, and who joined the government as minister of state and deputy prime minister in late June 1940.1 Laval spearheaded the destruction of parliamentary democracy and the Republic, introducing a dictatorship with Pétain at its head and Laval as the real power and successor behind him. This dictatorship was supported both by the Socialists and by the rightist parties.2 Laval told French senators that the constitution must be “modeled upon the totalitarian states,” including the introduction of concentration camps.3 Laval wielded power until December when he would be fired, but he made a comeback later.

Jean Guéhenno quipped in his diary, “Pétain and Laval do not speak for us. Their word does not commit us to anything and cannot dishonor us.”4

On July 14, Winston Churchill spoke these words: “This is no war of chieftains or of princes, of dynasties or national ambition; it is a war of peoples and of causes. There are vast numbers, not only in this Island but in every land, who will render faithful service in this war, but whose names will never be known, whose deeds will never be recorded. This is a War of the Unknown Warriors….”5 A “shadow army” of resistance groups rose all over occupied Europe, and it would contribute to the final victory.6 Countless unknown French citizens in the coming years would pick up arms and form the Resistance.

Resistance did not, and could not, begin with armed actions, but took many individual forms. In July, Marcel Demnet began acting as a human smuggler in Vierzon-Forges (Cher), the only city in France to be bisected by the demarcation line between occupied France and Vichy France. A young man employed at the town hall at the time, he responded to my questionnaire in 2002. In Demnet’s experience, before the war those who possessed firearms were mostly hunters, and the acquisition of a hunting gun was not regulated. Only members of shooting clubs could acquire revolvers and pistols after authorization by the prefect. There was a shooting club in Vierzon.7

Regarding the German decrees to surrender firearms, Demnet noted, “It doesn’t seem to me that in general the French in the occupied zone overwhelmingly obeyed these orders. The French are rebellious by nature and do the opposite of what one asks them to do. With the coming of the Germans, it was well within their temperament to engage in passive disobedience.”

What arms were kept by civilians and the Resistance? Demnet’s response: “Hunting guns and military rifles recovered after the debacle by farsighted French!” He added, “When the decrees appeared, some surrendered them to the occupation authorities but the others, certainly the most numerous, took care to grease them thoroughly, to slip them into protective cases, and to bury them or to hide them in places where they were more or less sure that the Germans would not be going to look for them—maybe with the hope that one day it would serve a good cause!”

For the next two years, Demnet worked for the Resistance to help as many as nine hundred people move clandestinely across the border. A favorite ruse for smugglers was to stage fake funeral convoys between the church (in the occupied zone) and the cemetery (in the free zone) over the Cher bridge.8 Then he was arrested by the Gestapo. He eventually would be released but went underground when he was about to be drafted as a forced laborer for the Germans, only to reappear to fight for the liberation of Vierzon in 1944.

This pattern repeated itself countless times. The Paronnaud family, farmers from Annezay in southwestern France, handed in their hunting weapons but tried to hide their new rifle. The mayor, already collaborating, threatened to denounce them to the occupation authorities. Their teenage sons, Yves and Robert, joined with others to form the nucleus of a resistance group. Before long their activities consisted of recovering hunting weapons, cutting Wehrmacht cables, hiding wanted people, collecting information on German troops, and writing anti-Nazi graffiti. They fought for the Resistance through the end of the war.9

Meanwhile, the Germans were settling in for a comfortable stay. From Paris, on July 31, the Chef der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich (MVF, or head of the military administration in France), decreed that the French could not hunt because they could not possess firearms, but that German soldiers could pursue game. Hunting would use the country’s resources to help meet the needs of the Wehrmacht and the German war economy.10

The way was thus paved for the plunder not only of the natural resources of the occupied country—its wild game—but also of its citizens’ firearms. Firearms of all kinds were confiscated not only to prevent any resistance, but also to be transferred to German soldiers for hunting and other purposes. Such orders were only a more organized form of the same kind of looting that took place by warring aggressors in ancient times. In the years of occupation, it was German policy to loot everything that could be looted, art and wine being conspicuous examples,11 but most prominent being labor and economic resources. As would be found in the Nürnberg (Nuremberg) trials, the pillaging of private property in all of the occupied countries was unlimited.12

However, such organized theft was not yet taking place as occupation authorities still observed some semblance of international law. An August 11 order of the Army High Command, General Staff of the Army, applicable in occupied France, Netherlands, and Belgium provided for “Weapons Confiscated from Private Citizens” as follows:

Pursuant to the Military Administration in France, in addition to captured weapons, Local and District Military Administrative Headquarters have turned over to military police staff weapons and ammunition confiscated from private citizens (mostly hunting rifles). These weapons will probably be returned to their owners later because they are not captured property. They must be separated from the captured property and held for pickup by Local and District Military Administrative Headquarters. Make sure that any documents showing ownership remain with these weapons.13

However, such registration of private property would prove illusory. A Nazi organization known as the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was at work registering Jewish cultural assets supposedly to protect them, but with the proviso that the Führer would decide their disposition. Historian Thomas Laub relates, “They described the registration of art as a measure comparable to military decrees ordering Frenchmen to register arms that could be used in a future conflict.”14 Such registration was just the first step to the confiscation of all such property.

Not foreseeing the harsh occupation to come, gun owner organizations promoted measures to identify people who had surrendered their firearms so they could be returned when peace came. The Saint-Hubert-Club de France, a hunting association, and l’Union Fédérale des Sociétés de Tir aux Armes de Chasse, a society of target shooters and hunters, supported the sending of questionnaires nationwide to do so. Monsieur Glandaz of the Saint Hubert Club met with Jean Chiappe, president of the municipal council of Paris, to implement the plan, which spread to departments throughout the occupied zone.15 Events would prove the scheme to be naive indeed.

Le Matin repeatedly published a communiqué from the prefecture of police headlined “Possession of Arms in Occupied Territory” beginning on August 13. It recited the German decrees of May 10, ordering the surrender of firearms, and June 20, ordering that hunting guns be included, and noted that the orders had been published in the Moniteur des ordonnances du commandant d’armes de Paris (Bulletin of Orders from the Military Commander of Paris), July 4, 1940. The communiqué concluded: “Following the return of many people to their homes, it is important once again to turn the population’s attention to their obligation to surrender their firearms, while reminding everyone that the offenders shall face serious punishments according to the Moniteurs des ordonnances provisions.”16

The duty to surrender arms was repeated in an edict dated August 20 of the MVF, who added that firearms must be turned in to the German authorities, while hunting guns must be surrendered to the mayors, who would keep them in custody. This applied to both usable and unusable firearms. All hunting guns and ammunition would then be transferred to the district military administrative headquarters, which would set up hunting-gun depots.17

The deadline for reporting the central registration of hunting guns and locations of depots would be extended from October 1 to November 10. Usable hunting guns were to be categorized as rifles, shotguns, or combination rifle/shotguns. The rounds of ammunition were to be counted.18

Along with enjoying French wine, women, and song, German soldiers wanted to try their luck at hunting. For the French, hunting was ended. As reflected in an August 29 order, the MVF repeated that “the local population in the occupied territory must surrender all hunting guns. Only members of the German Army may hunt.” The soldiers were admonished strictly to abide by the German hunting rules of the Reichsjagdgesetzes (Reich Hunting Laws) dated July 3, 1934.19

In the chaos, the decrees were not enforced uniformly. An August 21 report from the commune of Maisons-Lafitte noted secret field police (Geheime Feldpolizei) intelligence that “[w]eapons in the possession of civilians have not been surrendered in a consistent way. For example, one military office did not request the surrender of more than 30 rifles and shotguns, as well as several pistols, stored in the open in the office of a mayor. In some towns, surrendered weapons were apparently returned to their owners.”20

Similarly, the August 22 order of the day (Tagesbefehl) from Dijon observed that the surrender decree “has been repeatedly disregarded, mostly by people who are returning. The population must be reminded to observe the decree of May 10 conscientiously and of the penalties in case of violations.”21 Countless civilians had fled the German invasion and were now coming home.

In this early period, death sentences were by no means automatic for mere possession of a firearm. For instance, on August 26 a student named Pierre Lebelle in Rennes was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for flight and possession of weapons, and three student accomplices got eighteen months.22 As resistance activities escalated over time, death sentences became more common.

The French police assisted the Germans in all aspects of occupation policy. The situation report of the MVF for August reflected this: “The activity of the military police at District and Local Military Administrative Headquarters was limited to weapons searches, supervision of French police regarding surrender of weapons, search for and arrest of British citizens, searches for German emigrants, night watch, price control, and putting up of flyers against sabotage.”23 Aside from such provisions of occupation policy, German military law applied in the occupied zone to crimes where a German was the perpetrator or victim, and French law otherwise applied.

Service of the French police to the Germans was noted with contempt by Agnès Humbert: “At the Palis-Royal Métro station I notice a Paris gendarme saluting a German officer with obsequious servility. Rooted on the spot, I watch as he repeats the gesture over and over again for the benefit of every passing officer—stiff, mechanical, German already.”24

The German authorities trusted the French police with arms, but with reservations. As noted by the MVF, the French criminal police could be armed only with as many pistols as were needed, to include only one magazine with ammunition per pistol. Public notices of the orders banning weapons possession and the introduction of German criminal law were ordered to be provided immediately. As for the reports about weapons openly stored in a mayor’s office and mayors returning previously surrendered weapons to their owners, the district military administrative headquarters were reminded to secure surrendered weapons.25

The above was followed by an order condemning the unauthorized confiscation by some German officers of weapons from the French police, who were entitled to a sidearm, a rubber truncheon, and one pistol with nine shots.26 The need to establish a policy for issuance of weapons permits to French authorities and private entities such as banks and guard services was also recognized.27

A regular situation report (Lagebericht) began to be filed by each of the military administrative districts (Militärverwaltungsbezirke) in September 1940. They included District A at Saint-Germain-en-Laye (northwestern France); District B at Angers (southwestern France); District C at Dijon (northeastern France); District Paris; and District Bordeaux.

District Paris reported a raid netting only four illegal weapons.28 While noting some violations, District A reported that the threats of punishment seemed to have worked.29

District B had more substance. Bookstores were searched for illegal books and weapons were confiscated. About reports that weapons had not been surrendered, District B indicates that these mostly concerned farmers who had failed to turn in their hunting guns, which they either hid under hay or straw or did not bother to hide. Sentences ranged from one month to one year in prison.30 That was pretty lenient given that the death penalty could have been ordered.

A report added that German soldiers were being insulted with taunts of “boches” or “German pigs,” but admitted that the soldiers had caused the insults by being drunk or fighting with civilians.31 At least in some areas, the occupation was not going too harshly.

The MVF, which received the above reports, saw progress in disarming civilians with military arms but, given the large number of those who used to have the right to hunt, few hunting guns were confiscated.32 French hunters were perhaps not taking the threat of the death penalty seriously, or thought they would not be detected, as hunting guns were not registered.

A German decree requiring the registration of Jews was published on September 30.33 Vichy quickly fell in line. “The victor is inoculating us with his diseases,” wrote Guéhenno on October 19. “This morning the Vichy government published the ‘Statute Regulating Jews’ in France. Now we’re good anti-Semites and racists.” On the 22nd, Pierre Laval met with Hitler. “And since then, the whole country is trembling,” noted Guéhenno, adding, “What could that horse-trader have done? For what price did he sell us down the river?”34

“Through a haze of cigarette smoke we saw a stocky, greasy-faced little man behind the desk,” wrote Associated Press correspondent Roy Porter about his interview with Laval during this period. Banging his fist on the desk, Laval shouted, “I hope to God that the Germans smash the hell out of the British until they leave only a grease spot. Then, perhaps, France can take her proper place in European affairs without British domination.”35 His policy of collaboration was unabashed.

By now, military tribunals were hard at work punishing French citizens who had failed to surrender firearms. District A in Saint-Germain reported numerous cases, particularly in an area where house searches took place in retaliation for cut cables, netting old hunting guns and rusty pistols that had not been surrendered out of fear. The only death sentence reported concerned a man who fired a shot at a German soldier.36 Numerous searches found weapons possessed by Catholic priests and demobilized soldiers who just returned and were afraid to surrender their weapons.37

District A further reported the bringing of 54 cases of illegal weapons possession and the confiscation of 12,085 hunting guns, 115,305 hunting cartridges, and 404 pistols. The low number of prosecutions compared to the quantities seized indicates that most were voluntarily surrendered, either to German military officials or to French mayors or police. Captured property, that is, weapons taken from the French military, included 5,718 rifles and 425 handguns, together with 5 tanks, 42 artillery pieces, 2 mortars, 88 machine guns, and 2,486 sidearms (bayonets and swords).38

As reported from District B, hunting guns continued to be found, along with a few pistols seized in a search of ministers’ houses. In Châtellerault, 350 rifles, 50 machine guns, and 60 pistols were found in a basement.39 Besides weapons possession, crimes committed by the French included theft, anti-German demonstrations such as ripping off propaganda posters, currency export violations, illegal border crossings, slander of the German army, and illegal traffic with prisoners of war. Lack of French discipline caused most traffic accidents. Finally, it noted the death sentence against one André Eluau for using a knife to attack a sentry armed with a rifle who was stationed in front of the Hôtel de Paris in Le Mans.40

On October 25, General Otto von Stülpnagel replaced General Streccius as the military commander in France (Militärbefehlshaber, or MBF).41 Above all others, Stülpnagel would trust and rely on Werner Best, the central figure of the administrative staff.42 While serving in the next year and a quarter, he would order the execution of numerous French citizens for firearm possession. Earlier that month, the SS security service (Sicherheitspolizei und Sicherheitsdienst, or Sipo-SD) began operations to focus on the repression of Jews, religious groups, Communists, and other targeted classes.43

The MBF command staff reported appropriate measures taken against several cases of illegal weapons possession, some involving clerics. The military police secured abandoned military ordnance, including heavy weapons together with 160 machine guns and 1,200 handguns. Some 1,500 rifles and pistols and 27,000 hunting guns had been confiscated from civilians, proving that large numbers still lay in the hands of the population. The report noted that two German soldiers were sentenced to over five years’ imprisonment—one for rape, another for desertion—while a French citizen was sentenced for five years, and another for seven years, for weapons possession, and a third to ten years for demoralization of the troops.44

The military police of the District Paris filed a report for October 13 to November 12 that included an extraordinary number of arms confiscated or taken into custody by district military administration headquarters (HQ) #758,45 including a large number of rifles to be scrapped, 6,612 hunting guns, 1,034 shotguns and teschings (small caliber parlor rifles), 622 handguns, 10,555 hunting cartridges, and 10,000 hunting cartridge cases. Yet only 22 cases of illegal weapons possession were reported from HQ 758, suggesting that almost all of the confiscated arms were turned in voluntarily. Numerous firearm confiscations were also reported from other HQ sectors.

District A reported a decrease in illegal weapons possession in one area after a military court suggested new warnings to the prefect, who passed it on to the public. But in another area where arrests increased, to counter claims by many French that they failed to surrender their arms because they hid them too well, the court offered an amnesty for arms surrendered by November 20.46

“Cooperation with the French police is good,” reported District B. The search of a cave in Saumur based on confidential information yielded nothing, but weapons were found in a forest on the coast.47 The next monthly report noted 45 cases of illegal weapons possession and confiscations of 356 rifles, 65 pistols, 158 hunting guns, 1,121 rounds of hunting ammunition, and five kilograms of gunpowder.48

Similarly, District Paris reported, “We have a good relationship with the French gendarmes and police. Our cooperation with both of them is excellent…. They are fully at the service of the German offices.” This cooperation would have included ferreting out “illegal weapons possession,” of which only a dozen or so were reported. However, of “confiscated or secured objects,” all districts reported rifles and pistols and sizable quantities of ammunition (ranging up to 30,000 rounds in one district), and one district reported 850 hunting guns. “Captured property” included 1,300 rifles, 35 pistols, and 53 slashing and thrusting weapons.49

The fall hunting season was in full swing, about which various directives were issued. District B in Angers reiterated that hunting guns could only be issued to holders of army hunting permits. Useable and quality hunting guns stored in depots had to be maintained by workers paid by the mayor.50 Major General Karl-Ulrich Neumann-Neurode, head of District B, ordered that the depots be cleaned out of old guns, such as flintlocks without practical use as weapons for which ammunition was unavailable, and of old sabers and swords. They were to be returned to their owners either directly or through the prefect or mayor.51

The same directive clarified that no distinction existed between hunting guns surrendered by private citizens and those surrendered by dealers—both had to be transferred to hunting-gun depots immediately if they had not been already. Besides disarming the populace, this would ensure a bountiful supply for German hunters. The directive ordered a count of the number of hunting permits issued by the army as of the year’s end as well as the number of hunting guns issued to German soldiers, guns that did not need to be returned.

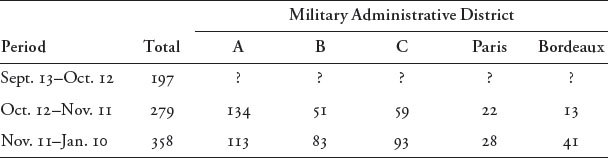

The MBF issued a comprehensive report covering four months from late 1940 to early 1941.52 French citizens were sentenced to over five years’ imprisonment for illegal weapons possession, assault on a soldier, and distribution of flyers favoring the enemy. The number of cases of illegal weapons possession was as follows:

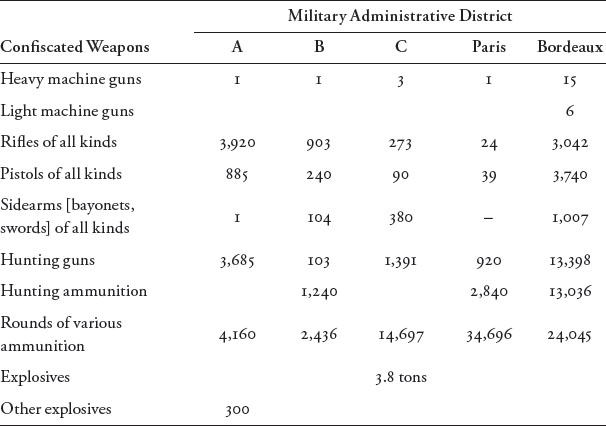

However, the number of confiscated weapons was far higher, suggesting that large quantities were surrendered to the Germans directly, or to the French authorities and then confiscated from them (see chart on next page):

As can be seen, 13,398 hunting guns were surrendered in Bordeaux, followed by 3,685 in District A at Saint-Germain-en-Laye (northwestern France), 1,391 in District C at Dijon (northeastern France), 920 in Paris, and only 103 in District B at Angers (southwestern France). Except for the latter two—nine times more hunting guns were surrendered in Paris than in District B—these figures may have reflected the prominence of hunting guns in rural France. However, more rifles were surrendered in District A than in Bordeaux, with far more pistols confiscated in Bordeaux than District A. The countless human realities behind the statistics were not recorded.

Those organizing to resist the occupation contemplated using underground publications and acquiring arms. On October 22, Alphonse Juge, representing the Popular Democrats (Démocrates populaires), organized a meeting in Montpellier in the living room of Professor Jean-Rémy Palanque. He proposed a plan of action around the review Temps nouveau. He was harshly interrupted by one of participants, P-H. Teitgen, who shouted, “Your idea is very well, my dear Juge, but it is not sufficient for us! You must obtain arms to use against enemies and traitors!”53

Similarly, in another context, Jewish resister David Knout insisted, “We have but one means of defending ourselves … taking up arms against the Germans.”54

The first arms of the Resistance were typically an old hunting rifle and an obsolete revolver model 1873. This obsolete revolver, which fired an 11 mm black-powder centerfire cartridge, was last produced in 1886, and was no longer a “military” arm banned to civilians by French law. Rifles such as the bolt-action carbine model 1892/16 8 mm Lebel, being “military,” had been banned from civilian ownership, but would be highly desirable by the future Resistance members.55

A member of the Resistance named Camaret was wanted by the Germans for hiding arms but had been tipped off and narrowly escaped. He crossed the border into the unoccupied zone on December 28, but would be in danger when he returned to Paris. Along with Guillain de Bénouville, he met with an attorney, Jacques Renouvin, who “told us that in addition to the military organizations which were hiding arms from the German commissions, other Resistance groups were already in existence…. They were unarmed, because the officers charged with hiding arms from the Germans would give them none.”56

Most would have to content themselves with unarmed resistance, even if only symbolic. Simone de Beauvoir noted in her diary that she had seen a hawker “selling comic composite pictures of gorillas, pigs, and elephants, each with Hitler’s head instead of its own.” But shoving a German soldier could be deadly. On the Boulevard Saint-Michel, she saw the following warning in red print: “Jacques Bonsergent, engineer, of Paris, having been condemned to death by a German Military Tribunal for an act of violence against a member of the German Armed Forces, was executed by shooting this morning.”57

At the end of 1940, France had experienced an occupation for six months that, while traumatic, was not the worst of all possible worlds. Regarding the focus of this study, French citizens who failed to surrender their firearms within twenty-four hours of Wehrmacht presence were threatened with the death penalty, but no instance of imposition thereof for mere firearm possession was reported. Probably thousands of violations were alleged, but incarceration, and not execution, was imposed.

Enormous quantities of personally owned firearms were surrendered to the Germans to be kept in arms depots. This provided a complete supply of hunting guns to happy German soldiers just in time for the fall hunting season. Unknowable but also enormous quantities of firearms were not turned in, prompting the occupiers repeatedly to admonish and threaten the occupied to comply with their orders. The French police received the highest praise for their collaboration with and assistance to the Germans.

To say that times would change for the worse would be an understatement.

“Laval is Hitler’s man, and collaboration is merely a fine word for servitude,” wrote Jean Guéhenno in early 1941.58 Major General Neumann-Neurode verified that cooperation with the French police was good, although they were not enthusiastic in enforcing rules about traffic and darkening houses. But illegal weapons, mostly hunting guns and pistols, continued to be found, and owners were sentenced by military courts. He added that churches and the houses of ministers had been searched for weapons, and two ministers had been sentenced for weapons possession.59

The above bears out the generalization by historian Henri Michel that “[i]n all occupied countries the Gestapo made use of the national police force, though placing little trust in it and had access to its files and saw its reports; they recruited from it volunteers who were completely at their service.”60 The records of firearm registrations were certainly within this cooperation. Although the Wehrmacht controlled the French police at this time, the tentacles of the Gestapo would increasingly assert themselves.

In the two-month period ending on January 10, some 61 cases of spying, 139 cases of sabotage, and 358 cases of illegal weapons possession were reported. The numbers of confiscated arms, surrendered or otherwise seized, were phenomenal: roughly 8,000 rifles, 5,000 pistols, and 19,000 hunting guns.61

In the same period, District A reported from Saint-Germain that numerous arms were surrendered mostly by wealthy people who were fearful of the penalties.62 District B at Angers noted sentences for anti-German demonstrations, weapons possession, theft, excessive prices, guerrilla activities, transfer of army goods, and resistance.63 An eighteen-year-old shoemaker was sentenced to death for finding a revolver and procuring ammunition.64 Hunting guns and revolvers were still in the hands of the population, and military courts intervened in fifteen cases. Roger Jeunet, an electrician working in the marine arsenal of Brest, was shot to death as he was aiming a pistol at two soldiers.65

MBF Stülpnagel issued a situation report for February praising the French police, who were supervised closely by the Germans, for their reliability and good work. The police prefect for District Paris reported several cases in which French police officers misappropriated weapons or kept them illegally, turning them over to the German authorities for prosecution.66

The MBF identified the main crimes committed as the cutting of communication cables, illegal crossing of the demarcation line, weapons possession, and giving aid and comfort to the enemy. Of eighteen death sentences, one was for illegal weapons possession and negligent bodily injury, and another for anti-German propaganda, illegal weapons possession, and failure to surrender anti-German flyers. Others were sentenced to prison terms for similar acts. Instances of illegal weapons possession for January 13 to February 12 were reduced to 176 from the previous month of 358. Thousands of firearms and tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition were confiscated.

Notices of the sentences of transgressors, often including several on one poster, were posted to deter future offenses. The following example would not have had much dissuasive force compared to the possible death penalty: farmer Jean Nolle was sentenced on March 17 to three weeks in jail for grenade and munition possession.67

Others got four years in prison for arms possession. In one case, the defendant possessed three rifles and over 100 rounds of ammunition that he stole from a captured property depot.68

Meanwhile, hunting guns continued to be appropriated for use by the occupation forces. Brigadier General Adolph, head of District B at Angers, issued an order on March 19 reciting orders from 1940 about the surrender of arms and purchase thereof for use by the occupation authorities.69 The hunting guns were not captured property but were private property belonging to those who surrendered them. Compensation for guns taken for the German forces would be determined by the MBF. The Reich Hunting Office (Reichsjagdamt) was taking 25,000 hunting guns from the depots at District A, while the commander in chief of the Luftwaffe (Ob.d.L., or Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe) was taking 20,500 from District Bordeaux. The latter suggests that this was a power grab by Hermann Göring, Germany’s hunt master and Luftwaffe chief, to take over the above total of 45,500 hunting guns as loot. Göring was notorious for looting art, and looting firearms would have satisfied his artistic and hunting lusts as well as provided booty for Luftwaffe fighters.

The German brass did enjoy the delicacies of French game, courtesy of special officers assigned to hunting. Reinhard Kops, an officer in the Abwehr (German military intelligence), was quartered in a beautiful room in the palatial building in the rue de Paris, where the other personnel of the Komandantur (commander’s headquarters) lived. In his memoirs, he recalled a hunt officer, a first lieutenant, who acted as a forest ranger in the forest of Compiègne, located sixty kilometers north of Paris, who provided game for the Kommandantur.70

Roast of wild boar was served at Kops’s first lunch at the headquarters. Kops wrote, “All arms had been taken from the French. In the Kommandantur, there was a huge room full of hunting arms, all carefully numbered and provided with the names and addresses of the owners.” The hunt officer and his minions had now replaced French hunters in controlling the stock of game.71 These must have been some of the finest confiscated hunting guns to be stored in such a place.

The issue of compensation for confiscated arms was being pursued at the highest levels. On March 24, the French minister, state secretary of national economy and finances, sent a memorandum to the MVF on the confiscation of arms belonging to private citizens. It stated:

Since the armistice came into effect, German authorities have confiscated, either directly or through the French police, all weapons and ammunition held by dealers for sale or by private citizens.

This confiscation was apparently conducted pursuant to art. 53, paragraph 2, of the Hague Convention of October 18, 1907. That treaty provides that weapons and ammunition belonging to private citizens may be confiscated by the occupying forces, but that they may not be considered captured property. This means that when peace is reestablished, they must be returned and their owners reimbursed for any damage suffered. In reality it appears, however, that the German authorities did not limit their actions to the safeguarding of objects confiscated in this manner. Rather, they used them and often in a way that will make their return impossible.72

The above-cited provision of the Hague Convention provided that “all kinds of munitions of war, may be seized, even if they belong to private individuals, but must be restored and compensation fixed when peace is made.”73 Hunting, competition, and other civilian firearms were not “munitions of war,” which meant military weapons. Needless to say, no firearms were ever restored or compensation made.

The above French memorandum went on to say that weapons dealers should be indemnified immediately for the arms confiscated from then since their businesses were destroyed. Confiscations from private citizens such as hunters and marksmen need not be compensated until later. It suggested that the confiscation of weapons from dealers be treated the same way as all other confiscations and that the dealers be paid the same way. Incredibly, it ended that the Germans would be responsible for these payments, but they could be deducted from the amounts due from France to Germany under the armistice.

A response concerning payment for confiscated firearms was issued by the MBF, apparently authored by Dr. Rudolf Thierfelder of the military administrative office (Kriegsverwaltungsrat, or KVR).74 Noting that in the beginning the plan was to secure about three million confiscated firearms, most could not be returned for the following reasons: (1) contrary to repeated orders of the MBF, ordnance staff treated many firearms as captured property and transferred them to collection centers without identification; (2) the Army High Command ordered 125,000 firearms to be transferred to Germany; (3) firearms loaned to German soldiers to hunt were no longer available; and (4) the safeguarding of firearms in collection centers was poor and many became useless.

A plan existed to negotiate compensation with the French government, but the criteria was unclear because the French government had ordered the surrender of some firearms even before the German invasion; some of the weapons collections at mayors’ offices were then taken over by the Germans, while others were destroyed in battle. It was thus impossible to determine the number of firearms appropriated from French collection centers and their owners. Moreover, in many cases, the Germans did not issue receipts for firearms surrendered at their request. German compensation to the French for confiscated firearms, like compensation for untold other items, was a hypothetical exercise that would go nowhere.

The MBF issued a situation report for March noting that, of eighteen French citizens sentenced to death, one was for guerrilla activity—shooting at a German airman who made an emergency landing—and two others were for illegal weapons possession and assault on a German soldier. There were 193 weapons offenses for the previous four weeks, the highest number being 76 cases from District A. District A also had the largest number of hunting guns confiscated, numbering 2,760. Not many firearms were surrendered in the other districts for this period.75 Not surprisingly, District A would brag about the good cooperation between German authorities and French police and gendarmes in a later report.76

As an example of the ongoing collaboration, what was described as an assassination attempt against Wehrmacht soldiers in Paris resulted in the apprehension of the terrorists with French cooperation. Fernand de Brinon, secretary of state and third-in-command for the Vichy government,77 declared to the press:

Two French construction site workers in a Paris suburb ran after a terrorist immediately after he had shot a German army soldier, and contributed to handing him over to the French authorities.

You know what Marshal Pétain thinks of these cowardly and vain attacks; he stigmatized them himself, by saying that they were committed against men who do their duty. Therefore, I have decided to congratulate, tonight, on behalf of the Marshal, the two workers who reacted with such determination and with courage, for their instinct worthy of good French citizens.78

This expressed Vichy’s collaborationist policy that sought to ingratiate itself to the Germans. As de Brinon told AP correspondent Roy Porter in an interview, “France has only one way to look and that is toward Berlin.”79

In this period, there was no organized armed French resistance. The Resistance instead was publishing underground newspapers and organizing for armed actions against the occupation when the appropriate time came. The Réseau du Musée de l’Homme (Network of the Museum of Man), a student group that used the museum’s duplicating machine, began publishing the newspaper Résistance the previous fall.80

The group did not have any weapons, related Noël Créau, a member of the group who responded to my questionnaire in 2002.81 Born in 1922, he was a college student living in a Paris suburb when the war came. He was supposed to go to the air force flight training school in June 1940, but the German occupation obviously changed that.

In prewar France, Créau explained, “[a]side from hunting guns, the law made it difficult to keep other types of arms.” When the Germans came, “I think most French people were reticent to hand over their hunting guns to the gendarmerie, and delayed doing so. But my father, as well as my father-in-law, veterans of 1914–18, buried their weapons in their gardens. They had to replace the shoulder stocks once they retrieved them.” They risked death: “It was common practice for the German police to execute firearm owners.”

That last comment requires qualification. Execution for mere gun possession would have been less common in 1940–41 but more ordinary after the SS assumed police duties in 1942 and also as armed resistance grew, particularly in 1944. Moreover, there were only about 3,000 German police in France. Most of the killing would be done by the French police and particularly by the Milice, Vichy’s paramilitary organization formed with German aid to fight the Resistance.

As Henri Frenay detailed in his memoirs, Resistance leaders changed their appearances and addresses often, and carried guns to defend themselves.82 Yet Communist operative Charles Tillon opined about his organization, “The Paris region did not contain fifty combatants capable of using any weapons at all in the spring of 1941.”83

The MBF issued a directive on May 20 regarding the management of hunting-gun depots. Noting insufficient adherence to previous orders, it mandated that each district must immediately establish a central depot large enough to store all confiscated hunting guns on shelves where they would be dry and secure from unauthorized access. Existing arms depots at district headquarters, mayors’ offices, offices of the ordnance staffs, or in other locations were required to be transferred forthwith to the central hunting-gun depot.84

Smokeless powder hunting guns that needed little or no repair were required to be separated from those that needed repair or were old or unusable. They were to be categorized by those whose owners were known and those whose owners were unknown. Usable guns would be sorted by type, that is, shotgun, rifle, three-barrel or similar combination, and small bore rifle. Each district would stock up to 1,000 hunting guns to be issued to soldiers.

All of the usable hunting guns would be immediately confiscated from private French ownership and placed in the depots for use by the occupying forces. The unusable and old hunting guns would be safeguarded and administered as confiscated private French property. Weapons that could be traced back to their owners would be listed with the name and address of the owner and the weapon number.

The hunting-gun depots would be set up by the war administrative inspector (Kriegsverwaltungsinspektor) assigned to forest services at each district. The staff person for forests and woods would supervise all hunting-gun depots of a district, and hunting officers would be in charge of the local administration of the depots. French assistance for care of weapons was subject to restrictions.

Finally, depots for hunting ammunition would be secured separately from hunting-gun depots. All hunting and small caliber ammunition from existing depots or other stocks were required to be stored in those depots. All other ammunition, including pistol ammunition, had to be surrendered.

Soldiers were not getting the guns free. Purchasers of hunting guns were given a receipt with the buyer’s rank and name, a recitation that the gun was purchased from captured property pursuant to AHM 1941, item 462, the price, the type of gun, manufacturer (if known), serial number, place and date, and disbursing officer. Payment for hunting guns was due by June 5.85

Meanwhile, the Vichy government was tightening the screws on Jews. The commissioner-general for Jewish affairs (Commissaire-général aux questions juives, or CGQJ), headed by Xavier Vallat, had been created in March. On June 1, Vichy issued a law prohibiting the possession, purchase, and sale of arms and ammunition by Jews.86

An internal debate within the Wehrmacht ensued about whether to declare an amnesty for new arms surrenders. The district military administrative counselor (Feldkriegsgerichtsrat) of the military court at Angoulême wrote on June 24 to Mr. Schmeichler, the MBF’s senior military administrative counselor (Oberkriegsgerichtsrat).87 He noted that the surrender decree of June 20, 1940, stated: “This order shall not apply to unusable weapons with sentimental value. [Für Erinnerungswaffen ohne Gebrauchswert gilt diese Verordnung nicht.]” However, the French translation of this sentence stated: “This order shall not apply to weapons with sentimental value that are not in use. [Ce décret ne s’applique pas à des armes souvenirs hors d’usage.]” Because of the mistranslation, many prosecutions had to be dismissed since the defendants believed that the decree did not apply to weapons of sentimental value if they were not being used.

Many people, the counselor continued, missed the original deadline but feared to surrender their arms later because of the penalties. Because of that, the courts in several districts proclaimed a new deadline for the surrender of weapons and granted an amnesty. Out of fairness, prior offenders had to be resentenced. Such a proclamation issued in October 1940 had no effect because the prefect delayed its publication and the new deadline expired in just twenty-four hours. The counselor concluded that the victorious Wehrmacht could afford to issue a new decree and grant amnesty, which would result in the surrender of numerous weapons and a reduction in prosecutions.

Dr. Grohmann, military administrative counselor (Kriegsverwaltungsrat) to the MBF, soundly rejected the proposal in a memorandum dated July 5.88 He doubted that the courts had authority to set surrender deadlines with the promise of amnesty. The twenty-four-hour surrender deadline in the decree of May 10, 1940, was absolutely necessary to protect the advancing troops. Some violators received death sentences that were carried out. Given the death sentences imposed so far, it would be inadvisable a year later to set a new deadline with the promise of an amnesty.

All hell was about to break loose with events that would dramatically increase activities of the Resistance. The German firing squads were about to shoot more French citizens than ever before, above all Jews and alleged Communists. People caught with anti-German propaganda or firearms, or who took steps to oppose the occupation, would be increasingly subject to execution.

1. Warner, Pierre Laval, 428–29; Pierre Laval, The Diary of Pierre Laval (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948), 63.

2. Shirer, Collapse of the Third Republic, 903–11, 919–46.

3. Warner, Pierre Laval, 197.

4. Guéhenno, Diary of the Dark Years, 3.

5. Guillain de Bénouville, The Unknown Warriors, trans. Lawrence G. Blochman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1949), 8.

6. Michel, Shadow War, 15.

7. Marcel Demnet, response to author’s questionnaire, November 13, 2002.

8. See histoire-en-questions.fr/vichy et occupation/ligne de demarcation/vierzon.html.

9. “Paronnaud Yves,” Mémoire et Espoirs de la Résistance, Association des Amis de la Fondation de la Résistance, www.memoresist.org/resistant/paronnaud-yves/.

10. BA/MA, RW 35/326, Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres, Vorschriften für die Jagdnutzung im Bereich des Chefs der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich, 31. Juli 1940.

11. Lynn H. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa (New York: Random House, 1994), 119–51; see Don and Petie Kladstrup, Wine & War: The French, the Nazis, and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure (New York: Random House, 2001).

12. United States v. Goering, 6 Federal Rules Decisions 69, 120 (International Military Tribunal in Session at Nürnberg 1946–47).

13. BA/MA, RW 35/544, Oberkommando des Heeres, Generalstab des Heeres, General-quartiermeister, Sichergestellte Waffen aus Privatbesitz, 11. November 1940.

14. Laub, After the Fall, 78.

15. “À nos adhérents,” in Le Saint-Hubert, organe officiel du Saint-Hubert-Club de France, n°4, 39e année, décembre 1940, 33.

16. “La Detention D’Armes Dans La Region Occupee,” Le Matin, August 13, 1940, 1. Reprinted in issues dated August 27, September 3 and 10.

17. BA/MA, RH 36/430, Erlass des Oberbefehlshabers des Heeres, Chef der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich, über die Verwaltung der Jagdwaffen und Jagdmunition in dem Bereich des Chefs der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich, vom 20. August 1940.

18. BA/MA, RH 36/430, Tagesbefehl Nr. 47 des Bezirkschefs C Qu./Ia in Dijon, 12. Oktober 1940.

19. BA/MA, RW 35/135, Div. Nachschubführer 157, Antrag zu den “Besonderen Anordnungen,” 29. August 1940.

20. BA/MA, RW 35/1195, Tätigkeitsbericht der GFP [Geheimen Feldpolizei] bei den Militärverwaltungen, 21. August 1940.

21. BA/MA, RH 36/430, Tagesbefehl Nr. 22 des Bezirkschefs C, Qu./Ia in Dijon, 22. August 1940.

22. Venner, Armes de la Résistance, 144–46.

23. BA/MA, RW 35/4, Lagebericht des Chefs der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich, Kommandostab, für den Monat August 1940.

24. Humbert, Résistance, 11.

25. BA/MA, RW 35/1196, Besondere Anordnungen Nr. 32, Chef der Militärverwaltung, Bezirk A, 2. September 1940.

26. BA/MA, RW 35/1196, Besondere Anordnungen Nr. 33, Chef der Militärverwaltung, Bezirk A, 3. September 1940.

27. BA/MA, RH 36/565, Bericht des Chefs des Militärverwaltungsbezirks Paris, Kommandostab, Stabsoffizier der Feldgendarmerie, Tgb. Nr. 51/40 betreffend Genehmigung zum Waffenbesitz, 12. September 1940.

28. BA/MA, RH 36/565, Monatsbericht des Chefs des Militärverwaltungsbezirks Paris, Kommandostab, Stabsoffizier der Feldgendarmerie, Paris, 21. September 1940.

29. BA/MA, RW 35/1196, Lagebericht für die Zeit vom 21. August bis 4. September 1940, Militärverwaltungsbezirk A, St. Germain, 8. September 1940.

30. BA/MA, RW 35/1254, Lagebericht September 1940, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, Gericht, 22. September 1940.

31. BA/MA, RW 35/1254, Durchschrift für den Chef des Kommandostabes, 20. September 1940.

32. BA/MA, RW 35/4, Lagebericht des Chefs der Militärverwaltung in Frankreich, Kommandostab, für den Monat September 1940.

33. Journal Official, no. 9, September 30, 1940, 92, cited in Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), 1:984; available at https://archive.org/stream/naziconspiracyag01unit/naziconspiracyag01unit_djvu.txt.

34. Guéhenno, Diary of the Dark Years, 28–29 (entries for October 19 and 24, 1940).

35. Roy P. Porter, Uncensored France (New York: Dial Press, 1942), 10–11.

36. BA/MA, RW 35/1198, Lagebericht für den Zeitraum vom 20. September bis 20. Oktober 1940, St. Germain, 20. Oktober 1940.

37. BA/MA, RW 35/1198, Lagebericht für Zeitraum vom 21. September. bis 20. October 1940, Chef der Militärverwaltung A, St. Germain, 24. Oktober 1940.

38. BA/MA, RW 35/1198, Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht für die Zeit vom 12. September 1940 bis 12. Oktober 1940, Militärverwaltungsbezirk A, Tgb. Nr. 796/40, 21. Oktober 1940.

39. BA MA, RW 35/1258, Ic Lagebericht für die Zeit vom 21. September bis 20. Oktober 1940, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, 23. Oktober 1940.

40. BA/MA, RW 35/1258, Lagebericht, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, Gericht, 23. Oktober 1940.

41. Laub, After the Fall, 43.

42. Allan Mitchell, Nazi Paris: The History of an Occupation, 1940–1944 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010), 6, 42.

43. Laub, After the Fall, 65.

44. BA/MA, RW 35/4, Lagebericht des Militärbefehlshabers in Frankreich, Kommandostab, für den Monat Oktober 1940.

45. BA/MA, RH 36/565, Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht des Chefs des Militärverwaltungsbezirks Paris, Kommandostab, Stabsoffizier der Feldgendarmerie, für die Zeit vom 13. Oktober bis 12. November 1940, 19. November 1940.

46. BA/MA, RW 35/1199, Lagebericht für den Zeitraum vom 20. Oktober bis 20. November 1940, Chef der Militärverwaltung A, 21. November 1940.

47. BA/MA, RW 35/1258, Ic Lagebericht für die Zeit vom 21. Oktober bis 20. November 1940, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, Gericht.

48. BA/MA, RW 35/1258, Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, 21. Dezember 1940.

49. BA/MA, RH 36/565, Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht des Chefs des Militärverwaltungsbezirks Paris, Kommandostab, Stabsoffizier der Feldgendarmerie, Tgb. Nr. 454/40. für die Zeit vom 13. November bis 12. Dezember 1940, 19. Dezember 1940.

50. BA/MA, RW 35/1257, Der Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, 21. November 1940.

51. BA/MA, RW 35/1256, Der Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, 18. Dezember 1940.

52. BA/MA, RW 35/4, Lagebericht für die Monate Dezember 1940 und Januar 1941.

53. Henri Noguères, Histoire de la Résistance : La Première Année, Juin 1940 - Juin 1941 (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1967), 1:162.

54. Anny Latour, The Jewish Resistance in France (1940–1944) (New York: Holocaust Library, 1970), 24. The author made arms deliveries for the resistance (p. 10).

55. Venner, Armes de la Résistance, 130, 143; Garry James, “French Model 1873 Revolver,” American Rifleman, November 2012, 120.

56. de Bénouville, Unknown Warriors, 13, 16, 18.

57. Simone de Beauvoir, The Prime of Life, trans. Peter Green (New York: Lancer Books, 1966), 511 (entry dated December 8, 1940), 570 (entry dated December 28, 1940).

58. Guéhenno, Diary of the Dark Years, 58.

59. BA/MA, RW 35/1260, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, 15. Januar 1941.

60. Michel, Shadow War, 258.

61. BA/MA, RW 35/286, 1941 Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich, Lagebericht Dezember 1940 / Januar 1941, 31 Januar.1941.

62. BA/MA, RW 35/1201, Lagebericht für den Zeitraum vom 15. November 1940 bis 15. Januar 1941, Chef der Militärverwaltung A, 16. Januar 1941.

63. BA/MA, RW 35/1260, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, Gericht, 16. Januar 1941.

64. BA/MA, RW 35/1261, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, Gericht, 19. Januar 1941.

65. BA/MA, RW 35/1261, Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, Südwestfrankreich, 22. Februar 1941.

66. BA/MA, RW 35/5, Lagebericht, Februar 1941.

67. Musée de l’Ordre de la Libération in Paris, exhibit #408 (on display April 2006).

68. BA/MA, RW 35/1203, Lagebericht für den Zeitraum vom 16. Februar bis 15. März 1941, Chef der Militärverwaltung A, 18. März 1941.

69. BA/MA, RW 35/1256, Der Chef des Militärverwaltungsbezirks B, 19. März 1941.

70. Juan Maler [Reinhard Kops], Frieden, Krieg und “Frieden” (Buenos Aires: J. Maler, 1987), 88. After the war, Kops escaped to Argentina and lived under the pseudonym “Juan Maler.”

71. Maler [Kops], Frieden, Krieg und “Frienden,” 89.

72. BA/MA, RW 35/624, Der Minister, Staatssekretär der nationalen Wirtschaft und Finanzen ; Betr.: Beschlagnahme der Privatpersonen gehörenden Waffen und Munitionen, Paris, 24. März 1941.

73. Hague Convention, Article 53 (October 18, 1907).

74. BA/MA, RW 35/624, Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich; Betreffend Entschädigung für sichergestellte Schusswaffen, Paris, 17. April 1941.

75. BA/MA, RW 35/5, Lagebericht März 1941.

76. BA/MA, RW 35/1205, Lage- und Tätigkeitsbericht für die Zeit vom 13. April bis 12. Mai 1941, Militärverwaltungsbezirk A, Tgb. Nr. 1131/41, 20. Mai 1941.

77. “1947: Fernand de Brinon, Vichy minister with a Jewish wife,” April 15, 2008, www.executedtoday.com/2008/04/15/1947-fernand-de-brinon-vichy-minister-with-a-jewish-wife/; “NBC Tells France,” Time, May, 26, 1941, www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,765661,00.html.

78. “Après l’arrestation à Paris d’auteurs d’attentats contre l’armée d’occupation,” Le Temps, April 25/26, 1941, 1. Also in “Apres l’arrestation des terroristes a Paris,” Le Figaro, April 25/26, 1941, 1.

79. Porter, Uncensored France, 67.

80. Humbert, Résistance, 23, 36.

81. Noël Créau, ancien président national, Amicales des Anciens Parachutistes S.A.S. et des Anciens Commandos de la France Libre, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, letter to author, February 4, 2002. For more details on Noël Créau, see www.francaislibres.net/liste/fiche.php?index=62760.

82. Frenay, Night Will End, 73.

83. Pryce-Jones, Paris in the Third Reich, 118.

84. BA/MA, RW 35/624, Verwaltung der Jagdwaffenlager, Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich, Paris, 20. Mai 1941.

85. BA/MA, RW 35/1275, Tagesbefehl Nr. 60 des Militärverwaltungsbezirks C, Nordostfrankreich, 21. Mai 1941.

86. Loi N°2181 du 1er juin 1941, J.O., 6 juin 1941.

87. BA/MA, RW 35/544, Gericht der Feldkommandantur 540, Aussenstelle Angoulême, Vorschläge hinsichtlich der Verordnung über Waffenbesitz im besetzten Gebiet, 24. Juni 1941.

88. BA/MA, RW 35/544, Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich, Verwaltungsstab, Abteilung Verwaltung, Verordung über den Waffenbesitz im besetzten Gebiet vom 10. Mai 1940, 5. Juli 1941.