So far we have considered several important issues that pertain to our knowledge. In chapter 3 we considered the sources of knowledge and there showed how experience is one of the most important sources of our knowledge as human beings. We know, for example, that the sun has risen today because we look into the sky and see it and feel it shining down on us. I know that my wife is speaking to me because I hear her voice and see her lips moving. I walk in the door to my house and know that dinner will be ready soon because I can smell the ribs in the oven coming to a finish. In all these cases, we claim to know based on experience of a particular kind: perception. In each of these cases we use different senses to make different kinds of perceptions.

There are two important questions that we will consider in this chapter. What are the various kinds of perceptions that we have? And second, what is a perception? Or put another way, how well do our perceptions tell us about the external world outside of our minds? On the face of things it may look like we should deal with the second question first. After all, we should want to know exactly what perception is before we consider the different kinds that we have. Yet, there are reasons for ordering our presentation the way we have. First, determining the various kinds of perceptions that we have is a much easier task than determining the nature of perception itself. Second, a survey of the kinds of perceptions that we have will help us later in dealing with the various theories of perception, but noting the kinds of perceptions we have will also raise many of the important questions that a given theory will have to address. Because of this, we will deal with the kinds of perceptions first and then deal with the more difficult question of the nature of perception. For now, we will take it that perceptions are the means by which we understand the world around us.

As human beings, we have perceptions about all kinds of things. Because of this, it will be helpful to identify some broad categories of perception. On the simplest level, we could say that there are two general categories: mental perceptions and physical perceptions. Mental perceptions refer to the awareness of things that we gain not by sight or sound but by thinking, reflecting on and remembering our thoughts. It is often the case for us that while reflecting on a conversation or past event we become aware of something we had not seen before when the original event or conversation took place. While it is true that these kinds of perceptions depend on prior physical perceptions, they are still different from them in ways that warrant separate treatment and consideration. In many ways this category of perception is much easier to deal with from an epistemological standpoint than are physical perceptions. As we will see, it is possible that we can be mistaken in our physical perceptions. But when it comes to mental perceptions, our confidence is much stronger. For example, I may be able to doubt whether or not the chair in my office is there or merely an illusion. But I cannot doubt that it seems to me to be in my office. Likewise, when I reflect on a past event and begin to realize something about that event that I had not previously realized, I cannot doubt that I am thinking about that event.

The more difficult task, from an existing logical standpoint, is accounting for our physical perceptions, or the perceptions we have via the five senses: seeing, touching, hearing, smelling and tasting. Let us start with an assumption that virtually all human beings have about these kinds of sense perceptions. When we see something or hear something, most of us believe to have direct and immediate access to the object that is seen or heard. In this view, perception is a kind of direct and immediate relationship between you the perceiver and the object that you are perceiving. We will give this basic assumption a full treatment in the next section on theories of perception because it represents a common-sense view of perception known as direct realism. We mention it here in brief because it provides an excellent starting point for considering the kinds of perceptions we have via the five senses.

In this view, we tend to think that perception is a two-part relationship between the perceiver and the perceived. But as we think about it for a moment, we quickly realize that there may be much more involved than this. In fact, in some cases with some of the senses, it looks like perception could actually be a three-part relationship between the perceiver, the perceived and some sort of intermediary object. To make this clearer, let us consider what happens as we perceive things with the five senses.

Consider what happens when we see a particular object. Most of us assume that our sight of the particular object gives us direct and immediate access to the object itself, such that we are really seeing the object. If that were true, then visual perception would be a two-part relationship between the object and perceiver. Yet, in some cases, it looks like this is too simplistic and thus potentially wrong. Take, for example, what happens when we look at the sun or a star. In the case of the sun we are looking at the object as it was approximately eight minutes ago, but not as it is right now. With stars, this is even more pronounced and significant, because the light we see in our perception at present represents the star as it was years ago or even hundreds or thousands of years ago. But if that is true, it is always possible that we are looking at stars that no longer exist. What this suggests to us is that visual perception may not be as direct and immediate as we first think. This also suggests that visual perception is a three-part relationship between the object, the light waves and the perceiver.

The same kind of observation could be made with regard to hearing and smelling. Again, we normally believe that when we hear a car approaching, we are hearing the car itself. We also believe that when we smell cookies baking, we smell the cookies themselves. But consider what happens in the case of sound. I have vivid memories of playing center field for my high school baseball team and standing in the outfield waiting for the ball to be hit to me. As any centerfielder can tell you, you will always see the ball hit about one second before you hear the ball clank off the hitter’s bat. This is because sound travels much slower than light, and thus there is a lag in time between events and their sounds. As in the case of visual perceptions, therefore, it looks like our sound perceptions are not as direct and immediate as we tend to assume, and that these kinds of perceptions detail a three-part relationship between object, sound waves and the perceiver. Likewise, this also seems true when it comes to smelling. When we smell the cookies baking in the oven, we are smelling the aroma given off by the cookies in the oven as they are cooking, but we do not immediately and directly encounter the cookies themselves.

Unlike seeing, hearing and smelling, the perceptions of touch and taste seem to be more direct and immediate, and thus are good examples of a two-part kind of perception. For example, when you reach out and touch your friend’s hand, you are really touching his hand. This kind of perception is direct and immediate and does not require some third object like sound or light waves to make it possible. Similarly, when you put a cookie in your mouth and taste the sweetness of sugar and chocolate, it seems as though your perception is again direct and immediate. Yet, even in these cases there are some reasons to think that there is more involved in these kinds of perceptions. Consider what happens when you dip your hand in a bowl of water and perceive it to be cold. Is it actually cold? According to empiricist philosophers, the answer is no; coldness is in the mind of the one perceiving the water but not in the water itself. A simple thought experiment will help illustrate why empiricist philosophers like John Locke and others would take this view. Imagine that you have three bowls of water in front of you: one burning hot, one lukewarm and one ice cold. Now suppose that you let your left hand soak in the bowl of hot water while also letting your right hand soak in the bowl of cold water for approximately two minutes. Then, after two minutes, you take both hands out of their bowls and place them both in the middle bowl that is lukewarm. To the left hand, which has been soaking in hot water, the middle bowl will feel icy cold. To the right hand, which has been soaking in very cold water, the middle bowl will feel burning hot. Or, in the case of tasting, consider what happens when we taste a particular flavor. In most cases, taste is rather simple and straightforward. But at other times, it seems as though even this kind of perception can be tainted. When I drink orange juice, for example, after just brushing my teeth, the taste of orange juice itself is misrepresented. Empiricist philosophers argue that this suggests that sensations such as hotness, coldness, sweetness or sourness are in the mind of the perceiver and not in the objects themselves.

Generally speaking, these are the kinds of mental and physical perceptions that we have on a daily basis. Given the questions that arise regarding the directness, immediacy and reliability of these perceptions, it is no wonder that philosophers and scientists have questioned this common-sense view of perception, in favor of other theories of perception. These considerations serve as a helpful backdrop to the various theories of perception to which we now turn.

Here we consider a question that perhaps many people have never considered. What happens in perception, or put another way, what is perception? Numerous theories have been put forward, but epistemologists put these theories into three general categories: direct realism or naïve realism, indirect realism or representationalism and phenomenalism or antirealism.

Direct realism. Much of what we have been describing in the preceding section about the kinds of perceptions that we have fits well with the direct realist theory of perception. In this theory, perception is thought to give the perceiver direct and immediate access to the objects of perception themselves. But this is not everything that can or should be said about direct realism. This theory is called a realist theory because it affirms the real existence of the object of perceptions which exist outside of the perceiver’s mind even while being unperceived. In other words, this view maintains that rocks and trees continue to exist even if we are not around to perceive them, and they continue to exist even after a given perception of them has come to an end. In short, this view is a realist view because it affirms the real existence of these objects in the external world. We call this direct realism because of the directness and immediacy of the access to external objects which are given in perception. Also, this theory holds that our perceptions of the world are caused by events and objects outside of our minds. For example, the reason I perceived a sharp pain in my arm this morning is because I received a flu shot. In this case, the perception is caused by an object in the external world which acted on me and my senses. This theory is sometimes referred to as a causal theory of perceptions.

To be sure, this theory of perception has much to recommend it. Among other things, it seems to be based on a strong basis of commonsense thinking about our perceptions. Rarely, if ever, do we think that we are not seeing things the way they really are in the world. For the vast majority of our sense perceptions, it does seem that what we see is what is really there. And if what we see is not what is really there, then why is it that so many of our judgments about the physical and external world turn out to be reliable judgments? For example, if I drive down the road in my car and see another car in the opposing lane swerve into my lane at breakneck speed, I would be a fool not to hit my brakes or swerve out of the way. If I did not swerve or hit my brakes, I would probably be in a crash and could lose my life. In this case, my visual perceptions give me real and true information about what is happening. As a result of these perceptions, I am able to make a reliable judgment about my course of action. Likewise, when I walk into my house and smell the aroma of rotisserie chicken cooking, I am properly informed by this perception that we are having chicken for dinner tonight. What these considerations show is that there is something basically true about the direct realist theory of perception.

Yet, as we saw above while considering the kinds of perceptions that we have, it seems that the direct realist theory of perception does not tell the whole story. In truth, it sometimes seems as though our perceptions are not as direct and straightforward as this theory would suggest. And, as we have seen, it does not seem to account for the various ways that our perceptions can be tainted by other factors. Specifically, this theory does not take into account the many physical and contextual factors that affect our perceptions. In the case of the three water bowls mentioned above, the lukewarm bowl feels hot to the right hand because that hand has been soaking in cold water. And it feels ice cold to the left hand because that hand has been soaking in hot water. The reason the orange juice tastes odd is because of the lingering taste of toothpaste. What all of this means is that while direct realism gives us a partial account of the real world, it does not tell the whole story. Because this theory assumes that things are exactly the way they appear to us in our perceptions, this theory is sometimes referred to as naïve realism.

Indirect realism or representationalism. A second theory of perception might be labeled as either representationalism or indirect realism and is normally traced back to Locke. He said, “Whatsoever the mind perceives in itself, or is the immediate object of perception, fault, or understanding, that I call idea.”1 In other words, for Locke, what we directly encounter in a perception is the idea formed in the mind from the senses, and not the object itself. So, perception of the external world is indirect and representational in nature.

Like direct realism, indirect realism is a realist theory of perception because it also affirms the real existence of external objects outside the mind. It differs, however, in thinking that our apprehension of these objects in perception is direct and immediate, and thus it is referred to as indirect realism. Jonathan Dancy notes the similarity and difference of these two perspectives. He says:

The dispute between the direct realist and the indirect realist concerns the question of whether we are ever directly aware of the existence and nature of the physical objects. Both, as realists, agree that the physical objects we see and touch are able to exist and retain some of their properties when unperceived. But the indirect realist asserts that we are never directly aware of physical objects; we are only indirectly aware of them in virtue of a direct awareness of an intermediary object (variously described as an idea, sense-datum, precept or appearance).2

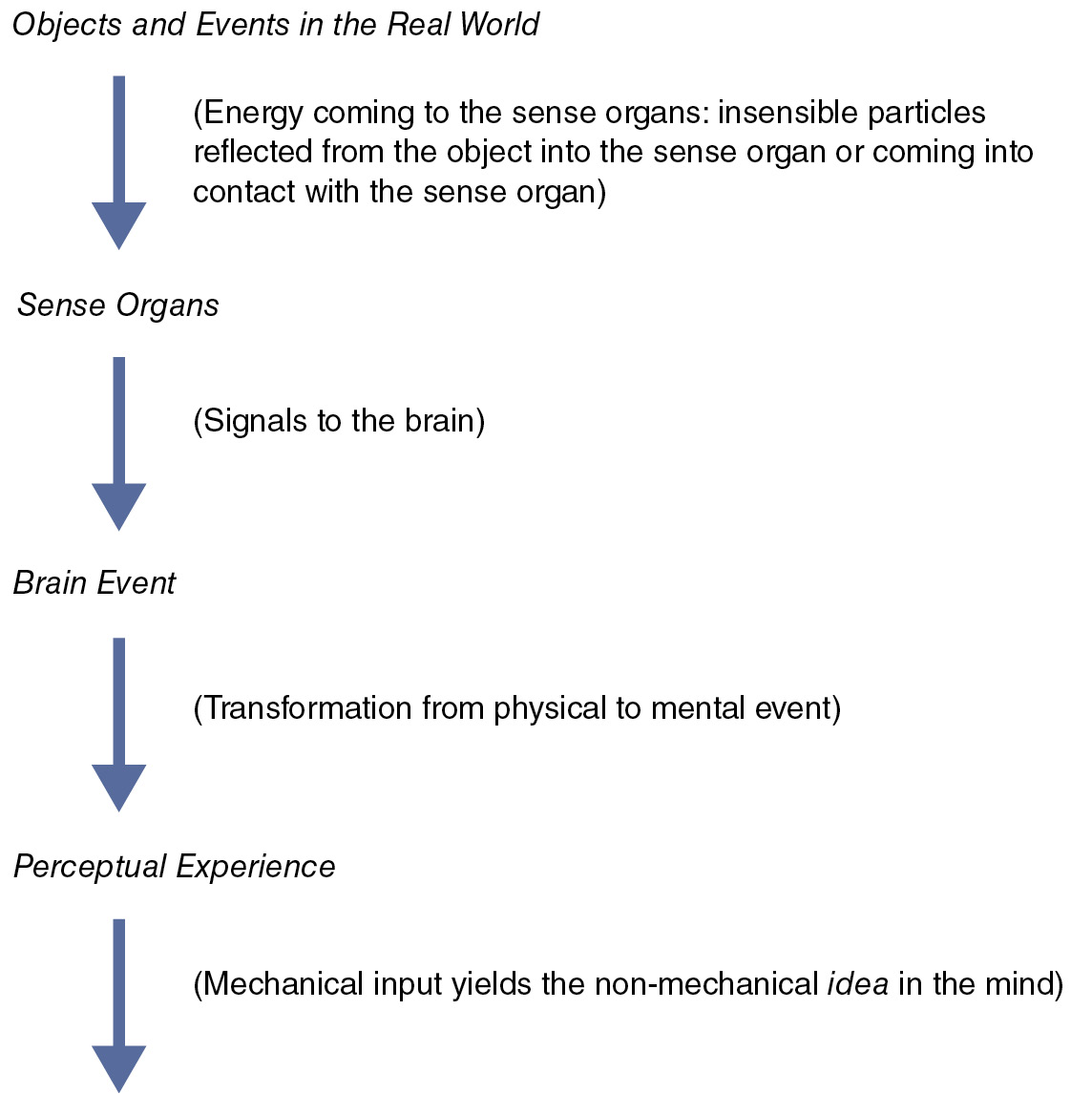

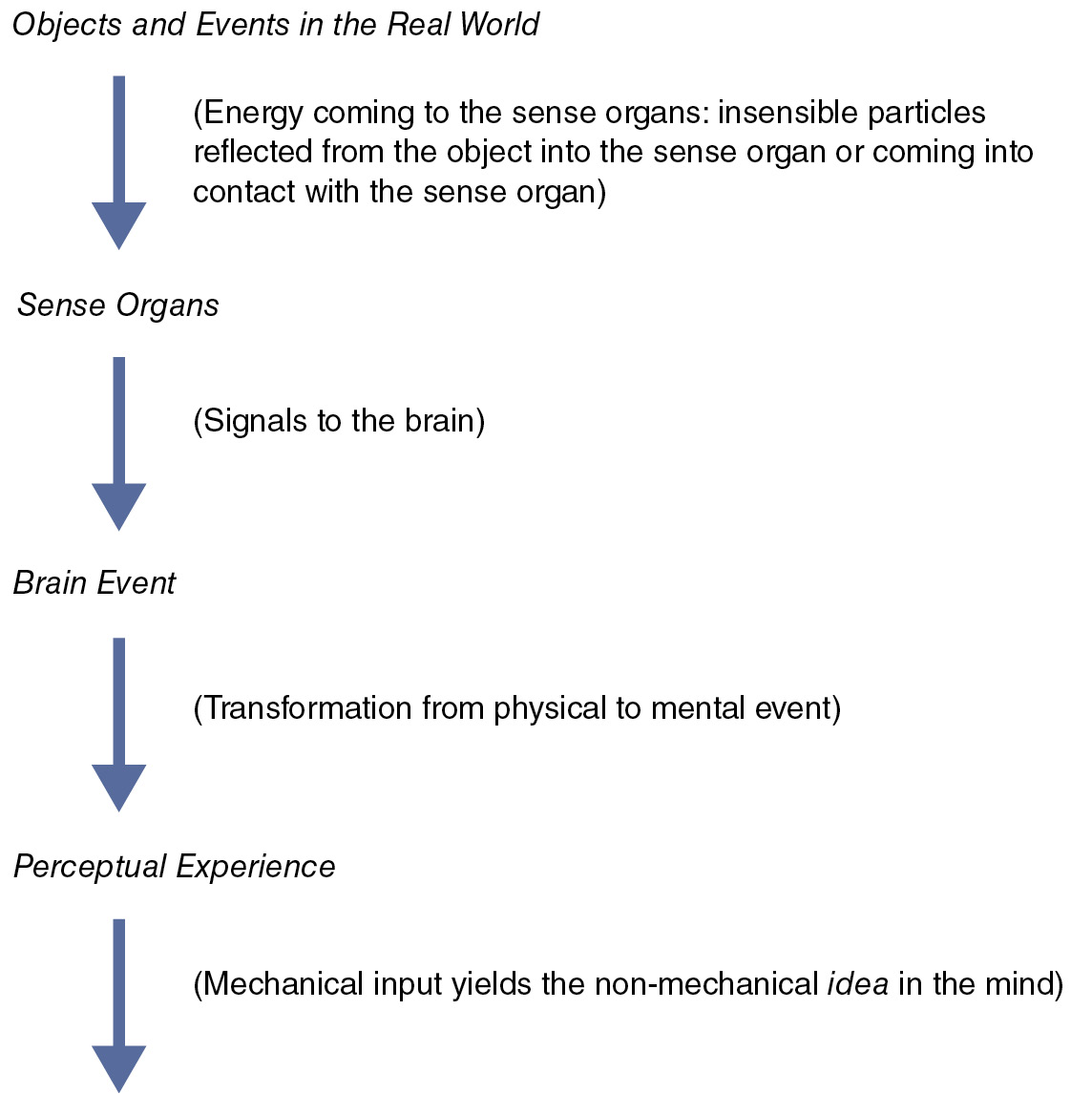

Labeling the perspective representationalism, Louis Pojman describes the process involved in this model of perception. In this account, perceptions begin with objects or events in the world, which are then collected by the sense organs, which in turn give signals to the brain. These signals are then processed as a brain event, which leads to nonphysical ideas in the mind.3 He offers a helpful chart (fig. 6.1) to illustrate the way perceptions represent the external world to the mind.4

Figure 6.1. Pojman’s View of Representationalism

So then, in a representationalist account of perception, we do not have direct and immediate access to the world. Rather, we apprehend the world as it is represented to us indirectly through the senses and our ideas that are formulated from the sense data. We do not experience things themselves but the images or representations of them.

As we have already seen, Locke argued that perception gives us indirect access to the external world through mental representations he called ideas. He is also known, however, for an important distinction between the kinds of qualities that we experience in objects. He called these primary qualities and secondary qualities. For Locke, a primary quality is a quality that is in the object itself and cannot be removed from it. He says, “Qualities thus considered in bodies are, first such as are utterly inseparable from the body, in one estate so ever it be; such as in all the alterations and changes it suffers, all the force can be used upon it, it constantly keeps. . . . These I call original or primary qualities.”5 Examples of primary qualities would include things like mass, number, solidarity and bulk. In other words, the qualities of being a physical thing or one thing are qualities that are in the objects themselves.

By contrast, a secondary quality is a quality that gives rise to a particular kind of sensation in us and does not genuinely reflect the object in the external world. For Locke, these qualities merely give rise to the sensations that we have about the object. He says, “Such qualities, which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves, but powers to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities . . . these I call secondary qualities.”6 Examples of these kinds of qualities would include blue, red, soft, hot or cold. These types of qualities, Locke thought, were not really in the objects themselves but in our perceptions of them. A short word of caution is in order here, as it is easy to misunderstand what Locke is saying. Locke is not suggesting that secondary qualities are completely mental constructs. He does argue that the object in question, which is perceived to be blue by us, has something in it that gives rise to bluish sensations. Nevertheless, whatever it is in the object that gives rise to bluish sensations is not itself actually blue. Rather, when this quality in the object that gives rise to bluish sensations is perceived by you and me, it is always perceived as blue. What Locke and other empiricists like him argue is that the mind perceives blue as it infers blueness from the experience of the objects themselves.

Like direct realism, this perspective has both strengths and weaknesses. On the positive side, this view clearly accounts for the way our comprehension of the external world might be mediated by mental processes or even tainted by other factors. It is true that we are sometimes mistaken about the things that we think that we see or hear. For example, perhaps we have all been to a restaurant buffet where we saw a nice piece of meat that looked juicy and succulent. After putting the meat on our plate and returning to our table, we find that the meat now appears gray and tough. Whether we knew it or not, we were enticed into eating the meat because of the way it appeared while still on the buffet. But while in the buffet line, the meat sits under red lighting, which gives the meat a different—and in this case better—appearance than it would have otherwise had. In this case, the appearance of the meat is tainted by the light that shines on it.

Despite whatever benefit indirect realism may have, many epistemologists note a major problem with this account of perception. First, it seems counterintuitive. Each of us sees things and feels confident that we are seeing what is really there. When, for example, I see the tree in front of me, I always think that I am really seeing the tree. So, no matter how well indirect realism accounts for the various ways we can be deceived in our thinking about our perceptions, it is plagued by the persuasive force of common sense. Second, if this perspective is true, then it seems that we can never be sure about anything that is presented to us through our perceptions. If we do not encounter the objects of the external world directly but only encounter them indirectly through the sensations and ideas that represent them, then how do we know that things really are the way our sensations and ideas suggest they are? The indirect realist might respond by saying we can have confidence in the representations because they are caused by the external objects of the world. But this seems to be an insufficient basis to guarantee that our ideas truly reflect the objects outside our minds, because what we end up seeing, hearing, tasting, and so on has gone through an elaborate mental process that only represents something outside the mind. How do we know the representation is right?

To illustrate this problem, we might consider what it would be like to live life inside a good flight simulator. Inside this simulator, we are constantly given visual and spatial indicators about things outside the simulator. We see clouds, runways, birds and raindrops. We also feel the movement of the plane as wind gusts hit the plane, forcing our bodies to think that we are really being moved by wind gusts outside of the plane. But are these really happening, and do these representations truly reflect the world outside the simulator? Unless we can step outside the simulator to see the world directly, we will never know. This seems to be the problem with indirect realism. According to this view, we never have direct access to the world, but only indirectly perceive the sensations and ideas in the mind that represent the external world. These representations might give genuine reflections of the external world. But then again, they might not. This view naïvely assumes a reliable correspondence between the objects of the world and our ideas of them.

Phenomenalism or antirealism. There is one final category of views on perception known as phenomenalism or antirealism. According to this view, perception is a phenomenon of the mind which is not necessarily connected to the world itself. To be clear, phenomenologists and antirealists do not necessarily deny the existence of the external world, as metaphysical idealists would be inclined to do. Nevertheless, in their view, perception is not caused directly by external objects outside the mind. Rather, perception itself has to do with data drawn from the senses and the internal mental processes, such that knowledge is a mental construct of the individual’s mind. As a result, this view sees a radical disconnect between mind and reality. As Jack Crumley II notes, this understanding of perception “denies that we should think of perception as involving mind-independent objects at all. Rather, physical objects are identified in some way with our sensations.”7 In other words, this view goes beyond indirect realism by emphasizing the role the mind plays in interpreting the data from the senses. In this view we perceive what the mind gives us. Thus, this view is much bolder than indirect realism because our sensations tell us nothing about the way things are in the world outside our minds.

At first blush, it might be hard to see how this is any different from indirect realism or representationalism. This is because they are very closely related. Both indirect realism and phenomenalism argue that perception does not give us direct access to the external world. But what makes phenomenalism different and more radical than indirect realism is the fact that, with phenomenalism, external objects do not dictate what we will perceive. This view is more extreme than indirect realism because it no longer assumes a real correspondence between objects in the world and the ideas in our minds.

Like indirect realism, this view has no problem accounting for the many times and places where our perceptions fail to properly reflect the world as it is. But, despite this, most philosophers—and most people in general—find this view problematic. There are two primary problems that we must note. First, what this perspective affirms is counterintuitive. The impressions we get from the world around us about its nature and detail are so strong that this theory of perception is hard to take seriously. We may very well have to grant that things can taint our perception such that we fail to see something at a given moment directly. Despite that, however, all our interactions with the world we live in are predicated on our ability to see what is really there. So, it is difficult to see how this perspective on perception is right.

Second, this account is challenged strongly by the advances made in modern science. If, for example, phenomenalism is right, then we should not be able to do most of the things that we do in the natural sciences. Consider the fact that we have been successful in putting human beings on the moon. This project required incredible precision and planning on the part of scientists as they considered the laws of physics. If their measurements and calculations had been off by even a slight margin, such accomplishments would have been impossible. If their calculations had not been exactly right, then we would have launched people off into the great expanse of space and they would have been lost forever. Instead, however, these astronauts arrived safely on the moon and returned to Earth to tell about it. All of this would have been impossible if our perceptions about the external world told us nothing about the way things are outside of our minds. In short, it seems as though modern science itself would be impossible if phenomenalism were true.

Where does this leave us, and which theory of perception is correct? It is hard to deny that our perceptions are sometimes tainted and that we fail to see things (or smell, taste, touch or hear) as they are. To deny this would be dishonest. As we saw at the beginning of the chapter, there are too many examples of times when something like this is going on in our perceptions. These difficulties have led some philosophers to affirm either indirect realism or phenomenalism. These perspectives have some advantages over direct realism because they suggest that we do not perceive things directly. Nevertheless, we have also seen that each of these perspectives on perception comes with some fatal problems. Phenomenalism takes what many consider to be an absurd position in that it suggests that we never know anything about the external world. All we know are our perceptions, which are not caused by objects outside the mind. This position is countered by our strong and persuasive common-sense intuitions and the successes of modern science.

Indirect realism seems to strike a middle ground between direct realism and phenomenalism by claiming we have indirect access to the external world with our mental representations, which are caused by the objects outside the mind. In this account, we know our sense data directly and the external world indirectly. But as we have seen, it is hard to see how we can ever be confident that our mental world squares with the external world. In other words, if indirect realism is right, how do we know that we know anything about the world itself, because we never have direct access to the external world?

Because of these concerns, many philosophers have returned to some form of direct realism. This does not mean, however, that they have rehashed what was said before. Instead, they have embraced a perspective that once again affirms a direct encounter with the external world but at the same time acknowledges the various factors that might cause us to misapprehend reality. Here is what we can and cannot say about our perceptions.

First, aside from times when deception or hallucination takes place, it does seem that our perceptions are caused by the objects outside of our minds. If this is the case, then it seems that we have access to things outside our minds and there is at least some sense in which our perceptions of the external world are direct and immediate. When a ball, for example, strikes me on the head, it is safe to say that I have direct and immediate access to the ball itself. After all, in this case I am in direct contact with the ball itself, not just the sense data of the ball. When I see my wife walk through the door of my office to bring me lunch, I see her and not just a bundle of sensations about her. In the case of the cookies I smell cooking in the oven, it seems that even here we are justified is saying that I have direct access to something about the cookies. Perhaps it is the aroma of the cookies and not the cookies themselves. But I am still experiencing something about the cookies that is caused by the cookies. Thus, most of us are still inclined to think that our perceptions give us some kind of direct access to the world around us.

Having said that, this does not mean that we have to be naïve about our perceptions, as if we have to think that what we see is what we will necessarily get. As some scientific experiments and a little reflection show us, there are various ways that our perceptions can be wrong. We have briefly hinted at a few of these in this chapter. So, while direct realism seems to give the best account of the nature of our perceptions, it is still a possibility that some of these perceptions can be wrong. Generally speaking, we can trust our perceptions, but we must not be naïve about the potential epistemological pitfalls that can lead to error.

Given the strengths and weaknesses of each theory of perception, we may never be able to say which theory is absolutely correct. We may, however, be able to adopt a methodology that allows us to take the strengths of each theory into account. In a wide variety of intellectual disciplines—such as philosophy, theology, sociology and science—much attention has been given to developing a methodology that will allow for genuine knowledge of the external world while also noting the potential for perceptual and cognitive error. This approach is described in various ways, but it most often is referred to as critical realism. When applied to the issue of perception, this approach holds that we can apprehend the external world itself (following the intuitions of direct realism) but can also be misled by both external and internal factors (heeding the warnings of indirect realism). Though it is a genuine form of realism, it emphasizes a need for critical assessment of our perceptions, beliefs and truth claims. It holds that we see the real world, but we might not see it exactly the way it is and should thus shun the naïveté of direct realism.

Later, in chapter 8, we will look at what is often called the epistemological virtues. There we will explore in more detail how it is that we might go about being critical in our mental engagement with the world itself. When we function with these kinds of mental virtues, we go a long way toward making sure that we are not misled by our perception of the world.

In this chapter we considered the issue of perception. We looked at the different kinds of perceptions that we have and at different theories of perception. Reflection and scientific evidence suggest that it is possible for some of our perceptions to be wrong, but this does not mean that we must embrace phenomenalism or indirect realism. In the next chapter, we explore the issue of justification.