6

There are not only flowers and bushes and trees and animals in the garden, but also a gardener who works there and who requires work tools for that garden. Some of them are as simple and as ancient as a pickax and a hoe; others are modern and sophisticated like the computerized irrigation system that I have never managed to fathom or activate without assistance. Twice a year, at the beginning of winter and beginning of summer, I hire a professional gardener who stops and starts it for me, because no matter how much I try to do it myself, I always manage to delete the irrigation program and have no idea how to reset it.

And there are work tools that are somewhere between a hoe and a computer, like the power scythe. I know how to operate this tool but expend much time and energy installing the cutting wire correctly, and even more time looking for the cocked spring, which always flies out of the rotating head during installation. This spring has its own ritual: it shoots out from between my hands as I work, falling and vanishing into the flora. It vanishes completely, purposefully concealed by the weeds. They have good reason: this power scythe is intended to obliterate them from the face of the earth.

To my great regret, I am no handyman. Whenever I try to repair one thing, I damage something else. My uncles and cousins, just as in the song “I have an uncle in Nahalal, and he can do it all”—and also moshavniks and kibbutzniks and those who served in the army with me—all know how to service a tractor and a jeep, install and repair water and electric systems, weld, do carpentry, erect a brick wall, cast a concrete floor, and they achieve all this quickly, confidently, without blundering or getting dirty.

Each one of them carries his own personal set of work tools in his pockets, the indispensable kinds that are carried everywhere. Today, it is invariably a Leatherman, but in my youth and childhood it was a pair of pliers, and sometimes a monkey wrench, known in Hebrew as a Swedish key and affectionately nicknamed “the little Swede.”

I recall a joke that people would tell back then, about three moshavniks who argued over which is the best work tool and should always be kept at hand.

The first said: “I take a Swedish key with me everywhere—it opens everything.”

The second said: “I prefer an English key—it opens everything.”

The third one said: “I prefer a Russian key.”

“What’s a Russian key?” his two friends wondered.

“A ten-pound hammer,” he explained, “which opens everything.”

Alas, the Swedish key and pliers and even the ten-pound hammer continuously drop from my hands, and almost always hit my toes. As for the Leatherman, I prefer my Swiss Army knife because it has a corkscrew—that is to say, its inventor recognized that man was born not only to toil. But I also have a work tool at hand which I carry in the pocket of my gardening overalls whenever I go down to the garden. This tool has no name, and so I’ll describe it briefly: It is a piece of plastic that resembles the handle of a screwdriver, and there is a small, hollow protrusion at one end which has a dual function: to pierce holes in water hoses in order to make water drippers and to wedge small spigots into holes pierced by woodpeckers.

The woodpeckers do not peck the hoses out of spite or thirst—that is done by wild boars and jackals that gnaw at the same hoses in order to drink—but because of an error they are making. The zoologist Professor Yossi Leshem, Israel’s first and foremost ornithologist, explained to me that the sound of water rushing through hoses is perceived by the woodpecker to be the very sound made by a worm in a tree. Furthermore, the woodpecker regards the outer layer of the hose to be as flimsy as a blade of grass. If I could only persuade the woodpeckers to peck the hoses solely in places where holes are needed, both functions of my tool would be unnecessary. But I have been unable to do this, and so I carry it in my pocket every time I go into the garden. To my joy, I am able to use it with relative ease, and to my sorrow I am frequently forced to use it.

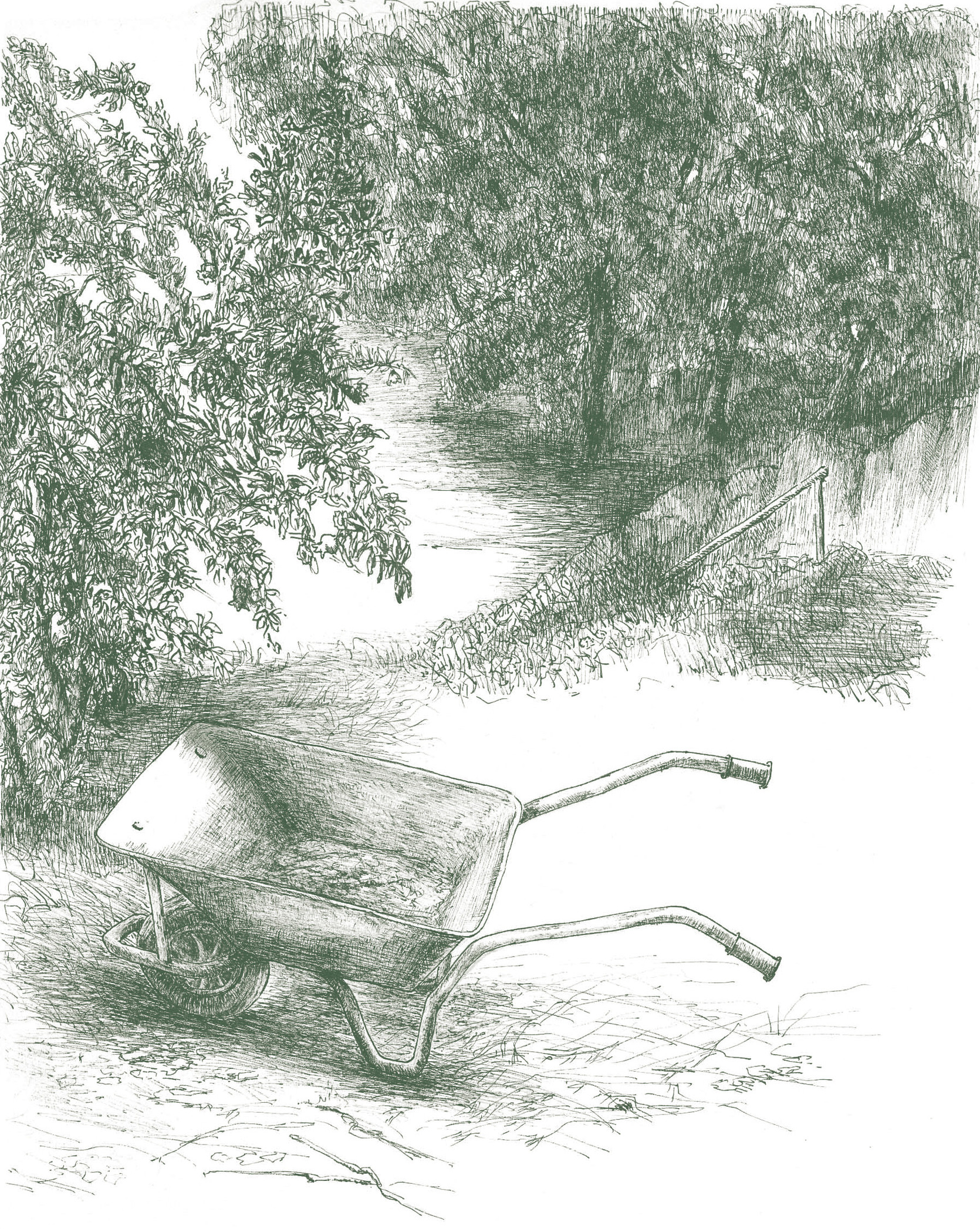

In truth, the amateur gardener should carry a few more tools and gadgets in his pockets: pruning shears, a penknife, a small hoe, a spade, drippers, all kinds of connectors and dividers, a jar of black ointment, and a sturdy trash bag. But the Americans have not yet invented overalls that possess pockets suitable for all this, and the Swiss have yet to invent a pocketknife that performs all these tasks. So I bought myself a box for my work tools, and I placed inside it everything enumerated above. I am very fond of this toolbox, and it seems the toolbox is fond of me too, because once or twice a week it joins me on a tour of the garden: I prune, uproot, plant, smear here and clear there, install and repair, and it waits patiently for its next task. The box also serves as a seat for me when I have something or other to do while sitting, and it only has one problem, that my most beloved tool cannot be placed inside it. On the other hand—the box can be placed inside it, because the tool I love most is the wheelbarrow.

I will not underrate the importance of the wheelbarrow in my life and the affection I feel toward it. Thanks to the wheelbarrow, I really appreciate the Chinese, who invented it, according to popular opinion. More precisely, not all the Chinese invented it but one specific Chinese man—a general who required it for military purposes two thousand years ago. His wheelbarrow was much larger than ours, and the wheel was located in the middle rather than the front of the barrow. A wheelbarrow with a central wheel can carry a load far heavier than that wheelbarrow we are familiar with today, because the wheel carries the entire weight, and the operator takes no part in the carrying, but it is more difficult to maneuver.

Plenty of water has flowed under the Yangtze River since then, and today the working man has at his disposal two-wheel wheelbarrows and even motorized wheelbarrows, but the simple wheelbarrow, familiar to all, still exists and it functions the good old-fashioned way. It was, and still remains, a kind of bathtub with two handles and a pair of legs on one side, and a single wheel on the other. The user stands between the handles like a horse standing between the shafts of a cart, but, unlike a horse, the user pushes rather than pulls.

Maneuvering the wheelbarrow is as simple and intuitive as riding a bicycle and, just like riding a bicycle, can be improved and made more professional—to tilt when turning, for example, and to thus improve the angle of steering and the diameter at which it is rotated. Indeed, the wheel is not visible to the eye, but acquired experience gives the operator a sense of where the wheel is.

Since purchasing the wheelbarrow, I have transported soil, stones, firewood, sacks of compost, sand and cement, flowerpots, trash and junk, weeds I uprooted, foliage I trimmed, crates of books from the car to my study, and my firstborn granddaughter, who at the age of three asked for her first wheelbarrow ride. I am not utterly certain as to whether the aforementioned Chinese general intended all this, but the wheelbarrow did not object and the little girl was as happy as a lark.

Every time I use my wheelbarrow, I wonder how I ever lived without it and am impressed by the ingenuity concealed within its incredibly simple structure. The years have made no significant changes to it. On the contrary, they have only refined and improved it, and as an ancient work vehicle, it has character, balance, and a maturity that not only benefits me but also gives me pleasure. And why mince my words? I believe that everyone, not only gardeners and farmers and builders, should have a wheelbarrow in their house. With small alterations in structure, pots and dishes can be brought from table to kitchen sink, a stack of books by the bed can be returned to shelves, washing transferred from washing machine to clothesline, a partner, male or female, who fell asleep by the television can be brought to the bedroom, where the handles will be lifted up and he or she will be poured into bed.

The wheelbarrow is a direct and natural continuation of the body. In this it resembles the hoe, the scythe, and the sickle—they, too, are ancient agricultural tools that have undergone no radical change for thousands of years and that I also use in the garden. With the sickle I crop weeds in places where it is impossible to get close enough with the power scythe. Hold it in your right hand if you are right-handed or with the left if you are left-handed; with the other hand grasp a bunch of weeds tightly, and then simultaneously pull it out while cutting.

As a child, I watched my uncles harvesting corn and durra with sickles. They harvested the alfalfa and clover with an ordinary scythe, not a mechanical one. That scythe appeared magical to me. Its blade, close to the ground and hidden among the stalks, could not be discerned with the eye. Only the bowing of the plants could be seen and the whisper of the cutting heard, and every few minutes the harvester pulled a small file out of his pocket to sharpen the blade with precise, measured movements.

As mentioned earlier, the contemporary scythe, sickle, and hoe still resemble their forefathers of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and so, too, the pickax and shovel, but the metal they are fashioned from today is far superior and much sharper. This is even more pronounced with regard to what we call here the Japanese saw, a magical instrument with which I cut branches much thicker than the span of the jaws of the largest pruning shears. The quality of the steel teeth and the angles of their sharp blade surprise me anew every time I use them. A branch as thick as my arm yields to it within five or six motions, and even an amateur like myself, with limited technical abilities, can appreciate a tool of such high quality.

And there’s another gardening tool, a very practical one that cannot be found in stores or garden nurseries. I do not know its name, but after having it explained to me I was able to set it up myself: take a metal pipe that is seven feet long and two inches in diameter, and insert the blade of a pickax into one end. With a few vertical blows, the blade can be embedded within the hose, and its other end, the one that protrudes, deepens and widens planting holes that the pickax and hoe are unable to advance through without hitting the walls of the hole. If anyone among the readers is familiar with the tamping iron, known in these parts as the balamina, the ancient stonecutter’s rod—I can tell you that this gardening tool is the balamina of soil.

Apart from all these implements, most of which were originally used in agriculture, I regularly use work tools from the kitchen: a wooden rolling pin helps me to thresh a variety of seeds; and I also make use of a number of sieves in order to separate seeds from chaff.

Once, Hebrew speakers used the word nafa, a sieve with fine holes used for sifting flour, and kevara, a sieve with wider holes, and mesanenet, a strainer that is smaller in diameter than the others. We no longer mill grain at home and hardly ever use a sifter in the kitchen, and we further describe all of these with the one word left over from this holy trinity—mesanenet. But a garden like mine, more primitive than other gardens, with plants far simpler and more ancient than cultured plants, demands old-fashioned tools and primeval names and simple craft. And so I use a nafa for sifting poppy seeds, a kevara for Agrostemma seeds, and a mesanenet for the chicken soup I prepare, because I like mine perfectly clear.