It was only years later, deep into The Tonight Show, that I learned Johnny had made up his mind the moment he saw me to move me above seven other candidates and make me his announcer for Who Do You Trust? By then, I knew that this was his style—he always knew instantly what he liked and he went for it at once.

Of course, on the Friday after my six-minute interview, I had no idea that my Philadelphia days were over. In fact, on Monday I was scheduled to go to Europe with the winner of a contest held by the sponsor of one of my shows. My wife didn’t want to go, but I decided to take my daughter Claudia and show her some of the glories of the old world. My ESP must have been working overtime because suddenly something made me cancel that trip.

Just two hours later, that “something” was on the phone, saying,

“Hi, Ed, this is Art Stark. When you show up, we want you to wear a suit.”

“A suit?” I asked, the way I would later repeat Aunt Blabby’s last words.

“Yes, Johnny wants to wear sports clothes, and we want to emphasize your size when you’re next to him.”

“But . . . what are you talking about?” I asked.

“Oh, didn’t they call you? You got the job; you start next Monday.”

I had been dreaming of a job like this since I was a small boy in Philadelphia pretending that a flashlight was a microphone. Now, however, in addition to liking my voice, Art Stark liked the contrast between a six-foot-four, 220-pound Irishman and the Midwestern WASP of whom there was considerably less. It had seemed like forever since my visit to Johnny—waiting for a phone call that I was certain would never come.

WHO DO YOU TRUST?

On Monday, October 13, 1958, I began work as Johnny’s announcer on Who Do You Trust? The game was the least important aspect of the show. It was simply a vehicle that allowed Johnny Carson to show off his genius. My job was to introduce the contestants, do the commercials, and have occasional brief conversations with Johnny at the top of the show. When I came out for the first time, Johnny established a relationship that would last for almost fifty years. Pretending not to see me, he suddenly turned and said in surprise, “Lothar, you startled me!”

Johnny and I had many wonderful memories, both on and off the show. On his farewell show, Johnny said, “A lot of people who work together on television don’t like each other, but Ed and I have been good friends. You can’t fake that on TV.”

You may be thinking that Lothar is the president of Sri Lanka, but he was the huge manservant to a cartoon character named Mandrake the Magician. Johnny was announcing that the big guy and the little guy—well, reverse that billing—were on their way.

He then gave me a memorably warm welcome: he set fire to my script. As I was about to make my announcement for the first of six sponsors whose copy lines were on a sheet of paper in my hand, Johnny decided they all could go to blazes. And from that day on, whenever I began to read the opening announcement, he set fire to the bottom of my script, and so I had to read the opening as fast as I could before all the words burned up. No announcer ever had And because Johnny thought that torching my copy had gone so well, he actually did it on every taping of the show for the next four years! I had to memorize all the copy and wing it as well as I could, hoping that at least I got the names right. If the copy said, “Keebler chocolate chip cookies with the big extra chips are absolutely delicious,” the fire edited my text to “Keebler . . . absolutely.” If the copy said, “Dristan is the miracle for your eustachian tube,” I managed, “Dristan . . . for your tube.” such a trial by fire. I was the first one who ever read charcoal. Of course, Johnny’s little cookout got a huge laugh.

I do not exaggerate about this particular little conflagration.

Johnny wanted to enjoy the sight of me treading water in the tube, instinctively knowing I was professional enough not to go under. One of those sponsors should have been Zippo.

In those four years of Who Do You Trust? Johnny and I shaped our unique relationship on the air. I set up the jokes and he got the laughs, sometimes at my expense. One day, he crawled under the camera and gave me a hot foot while I was doing a spot, distracting me so much that instead of saying, “StayPuff makes it easy to pin a diaper,” I said, “StayPuff makes it easy to pee.”

“I think there’s something wrong with him,” my wife said one day.

“No,” I said, “there’s something very right.”

“Why does he think you’re a barbecue?”

“He knows exactly what I am.”

“Well, I hate for the children to see you on fire.”

“I wonder if there’s a suit my size in asbestos.”

I also wondered if Mr. Brady saw how quickly Johnny was smoking in every way on Who Do You Trust? On one of the early shows, a contestant was telling Johnny at great length about a pregnant armadillo she had and how happy it was to “be with armadillo.” Johnny was clearly bored by this report of scaly gestation, and I could see that the woman was an anesthetic for the audience too. The appeal of maternity doesn’t really pick up until you’ve moved higher than camels.

Suddenly, Johnny asked the woman, “Tell me, how come you know these things if you’re not an armadillo?”

Another time, one of the contestants was a Latin Quarter showgirl wearing a poured-on dress, Day-Glo makeup, and a hairdo that could have crowned Miss American Hooker.

“On your way to a Four-H Club meeting, are you?” asked Johnny, and I knew that I was on my way too.

He’s got it, I thought. This man thinks funny. I’ve hitched my wagon to a star.

One day the jackpot question for a young couple was “Give the difference between an African elephant and an Indian one.”

I don’t remember if the couple gave the right answer, but I do remember what Johnny said: “Well, at least they don’t visit each other. Not too many African elephants in New Delhi. Or any deli. They don’t need more tongue.”

This, I thought, is going to be fun. I’m tied to a wit as fast as Groucho’s.

For another couple, the jackpot question was “Name the female flier who was lost in the South Pacific.”

After that couple had correctly answered, “Amelia Earhart,” Johnny said, “You know . . . Amelia Earhart was more like a guy. Most women would have stopped at Guam for directions.”

And then there was the jackpot question that was a remarkable preview of things to come. The question was “Name the man who explored North America before Columbus.”

The answer was Eric the Red. After a woman gave the answer, Johnny offered the smile that would enchant America and said, “That could also be the answer to ‘What did the Nixon committee call Eric?’”

Neither of us knew it, but Carnac the Magnificent was being born.

Another day, after Johnny had given the audience a few such gems, I said to him, “Johnny, you’re a natural. I don’t understand how your CBS show could have failed.”

“Because they wouldn’t let me be natural,” he replied. “Our reviews were good, but the network people wanted higher ratings and I was dumb enough to let them start telling me what to do.

‘We’ve got to make the show important,’ they said. Now how the hell were they going to do that? Have me come on to ‘God Save the Queen’? They wanted a funny Edward R. Murrow. Ed, I’m an entertainer—no more, no less. I learned the hard way that you have to follow your own instincts.”

“And also,” I said, “anyone who never fails can never have success.”

“You’ve been eating Chinese.”

“Well, I know you’re a funny guy. And your interviewing is great. You’ve got the curiosity of a child.”

“You mean a child who’s curious. I know some curious children. And I know some who are just plain strange.”

FEARLESS

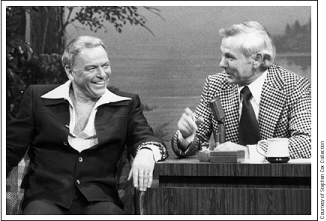

Yes, from the beginning, Johnny knew precisely what he was and he stayed true to it. He was as unpretentiously brilliant as Noël Coward, who described his own gift as “a talent to amuse.” And

Johnny enjoyed sparring with the Chairman of the Board, whether on The Tonight Show or in Jilly’s.

Johnny had the self-confidence of Coward. In fact, he was fearless— of man or beast.

Jim Fowler, an animal trainer, once brought a tarantula to the show and put him on Johnny’s hand. With a sick smile, Johnny asked, “He’s poisonous, right?”

“Not that poisonous,” Fowler said.

“So I won’t be that dead,” said Johnny.

“Just don’t anger him.”

“How am I going to make a tarantula angry? By saying, ‘You’re ugly’?”

“By blowing on him.”

“I never blow on a tarantula,” Johnny said. “That’s one of the things my mother taught me.”

And Johnny was unafraid of something even scarier than the tarantula—Frank Sinatra.

Johnny’s courage was burned into my memory one night early in the run of The Tonight Show. It was well past midnight and we were sitting in the piano bar of a Manhattan restaurant called Jilly’s, basking in the glow of vodka sours and looking forward to our two-man jam session of voice and drums. Suddenly, Frank Sinatra came in and the congregation fell silent, for Sinatra’s appearance in Jilly’s was a religious experience. Everyone just watched in reverence as His Holiness walked past the bar. No one would dare speak to him unless he spoke first. No one wanted to be turned into salt. And then, throughout the restaurant the voice of Johnny Carson was heard: “Dammit, Frank,” he said, “I told you ten thirty!”