seven

“Heeeeere’s Johnny!”

and “Hi-Yooo!”

While he hosted Who Do You Trust? the name Johnny Carson was hardly a household word. One evening in the spring of 1960, Johnny and I were having dinner at Sardi’s, a restaurant in Manhattan’s theater district with walls covered by caricatures of show business stars. When we were almost finished with our meal, our waitress approached the table.

“Would you like more coffee?” she asked me.

“Yes, please,” I said.

She refilled my cup and then walked away, ignoring Johnny.

“I see you’re dining alone,” he said, and then he looked up at the walls and said, “My picture won’t be there. I’ll have to go for a post office.”

Another time at Sardi’s we noticed two ladies at a nearby table who were looking at us and smiling.

“You go,” we heard one of them say.

“No, you go,” said the other.

“No, Helen, you.”

As Helen rose and approached us, Johnny and I braced ourselves for an autograph request. When Helen reached us, she asked, “If you’re not using the cream, may we have it?”

Athough we didn’t know it, The Tonight Show would be ending any wish for privacy that Johnny or I might have had.

IN SEARCH OF LAUGHTER

Just before taping time at NBC on Monday, October 1, 1962, three weeks short of his thirty-seventh birthday, Johnny left his seventh-floor office, picked me up, and we started walking down the stairs together into the unknown.

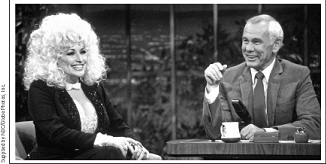

Dolly Parton, who also had a big heart, let Johnny know that every part of her was real.

“Johnny,” I said to him, “this may not be the best time to be asking this particular question, but I really don’t know what my role on the show will be.”

“I don’t know my role either,” he replied. “Let’s just go down and entertain the hell out of them.”

That was the only advice I ever got from him, but that was enough. “Let’s just entertain the hell out of them” became the guiding spirit, the fundamental philosophy, of The Tonight Show. Both Johnny and I instinctively knew that we were two explorers in search of laughter and there were no maps.

We went on the air, he was introduced by Groucho Marx, there was great applause, and then Johnny came out and said his first words: “Boy, you would think it was Vice President Nixon.”

He then went on to say, “Seriously, ladies and gentlemen, this is kind of an emotional thing for me. I don’t mean to be maudlin, but I know that a lot of people are watching all over the country. I have only one feeling as I stand here before so many people. I want my na-na.

”

A LOVABLE BAD BOY

Johnny was able to entertain the hell out of them for thirty years because he was the best thing an entertainer can be: an original. And he was not just an original but such a natural one that the work behind the wit never showed, just as no fan ever saw the effort beneath Joe DiMaggio’s gracefulness. Johnny was probably the only man in show business who could have these easy exchanges with Dolly Parton, and Raquel Welch:

“You know, Johnny,” said Dolly, “people are always asking me if they’re real.”

She wasn’t referring to her teeth.

“Oh, I would never do that,” Johnny said with his bad boy grin.

“Well, I’ll tell you.”

“Must you?”

“These are mine.”

“Both of them?”

“Both.”

“Dolly, I do have guidelines on this show, but I’d give a year’s pay to peek under there.”

With Raquel Welch, mere innuendo was enough for the laugh.

Seated close to him, Raquel was wearing a blouse that left no doubt about her gender. After Johnny had made some quick retort to her, she said, “Oh, that’s good.”

“Yes,” he said, “any opening at all, I jump right in.” And then the puckish grin and “Oh-oh.”

Johnny loved sexual jokes and always knew precisely how bold they could be because he had a special “lewdness license” as the lovable bad boy from the prairie—the boy who said, “When turkeys make love, they think of swans.”

TEA TIME MOVIE

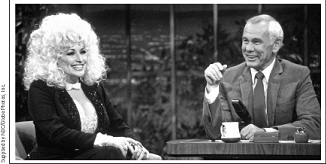

One of the running characters that Johnny played was Art Fern, the idiotic host of Tea Time Movie. However, Art Fern was smart enough to have beside him a sometime—well, really almost no time—actress named Carol Wayne, a young woman who had received more than her share from puberty. In a moving salute to her bosoms, Johnny said, “She could have nursed Wyoming.”

Johnny as Art Fern with Carol Wayne who brought an extra dimension to Tea Time Movie.

In one Tea Time Movie spot, Carol came out with the model of a house in front of her chest and Art asked the audience, “How would you like to get your hands on one of these?”

Moments later, she was holding a fan of insurance policies, as Art delicately said, “Take a look at what we cover with these policies. And then take a look at what we don’t.”

In another Tea Time Movie spot, Johnny said that Carol would never drown because she carried her own life buoys. In tragic irony, drowning is precisely how Carol died in a Mexican bay early in 1984. Her replacement, Teresa Ganzel, was pretty and played well with Johnny, but she lacked a certain dimension.

Because he had the face of a fallen choirboy, when Johnny used suggestive material, he was able to get big laughs with obvious lines. One night, a female pretzel maker was showing him how to shape the strands. Johnny tried it, but couldn’t twist his strand into a pretzel.

“I don’t think yours is long enough,” she said.

“I’ve heard that before,” said Johnny.

And the audience roared, even though most of them had heard this obvious wordplay many times before.

Because of the special license given to his distinctive style, Johnny always knew exactly how far into blueness he could go— territory he again visited when a butterfly collector came to the show and showed Johnny a few specimens under glass.

“I mounted all these,” he proudly said.

“How do you mount a butterfly?” asked Johnny. “It must be very difficult.”

The gag was moderately amusing, but another obvious one and one other comics might have come to. But Johnny’s look, an endearingly funny blend of angel and devil, was what lifted the line to detonate laughter.

AS PLANNED AS A FOOD FIGHT

“Ed,” he once told me early in our New York run, “I know we’ve got all these writers, but let’s never do anything that sounds like it’s had a lot of planning.”

“Don’t worry, Johnny,” I said. “This show feels as planned as a food fight.”

“Let’s keep it that way,” Johnny said. “I don’t want to come out with something that smacks of a month’s preparation; I couldn’t keep that up every night. I’m just going to be my natural self and we’ll see what happens.”

What happened was the high-water mark of American TV, especially when Johnny threw Don Rickles into a hot tub.

“HE’S GONNA ENTERTAIN US!”

Johnny acted less like a star than any star I have ever known, although he was always aware of his place on the public scene. He drove himself to the studio alone, carrying his lunch in a paper bag. It was probably the only time anyone had ever brown-bagged it in a white Corvette.

One evening, we dropped into a nightclub to catch the act of a young comedian. We had barely sat down at our table when a large man came over to us. The look on his face told me that he wasn’t looking for an autograph. After hovering over us for a few seconds, he pulled Johnny up by one of his arms and dragged him to a table full of his friends—although it was surprising that a man like this had any friends. While I wondered which way I would throw him, he turned to the people in the club and cried, “Hey, everyone! This is the great Johnny Carson! He’s gonna entertain us!”

I could see that Johnny also wanted to rip into the guy, in spite of the gentleman’s size; but Johnny knew the newspaper stories he would be creating, and so he turned to me and said, “Ed, let’s get out of here.”

Furiously, he twisted away from the guy and we returned to our table, where we decided that the evening had already been more than enough fun and it was time to leave while Johnny was still conscious. Johnny was well aware that all his improvisation had to be with his tongue, not his fists. Or course, after fighting back against any of the large fools who came after him in bars, Johnny might have seen stories about the length of his convalescence.

“HEEEEERE’S JOHNNY!”

As the date of Johnny’s first Tonight Show approached, I had been thinking hard of a unique way to introduce him. For Jack Paar, Hugh Downs had said, “And yours truly, Hugh Downs.” But “yours truly, Hugh Downs” just didn’t feel right for me, and it just didn’t seem enough to say, “And now, Johnny Carson.”

And then, just before Johnny and I walked down one flight to NBC’s sixth-floor studio that first time, I remembered when I had been doing early radio that I had a clever way of introducing people whose names contained Rs: I richly rolled the Rs in those names.

When I walked onto the first Tonight Show, I walked into a thirty-year dream.

Well, the gods must have been smiling at me because out of my big mouth on that first show came a cry to stand beside “Heigh-ho, Silver!” as one of the most memorable phrases in television history. To several million Americans, I said, “Heeeeere’s Johnny!”

The slight pause between my bellow and Johnny’s name was less dramatic than Edward R. Murrow’s “This . . . is London,” but our show was less important than World War II.

“HI-YOOO!”

How did my “Hi-yooo!” come to be, you are asking? Even if you’re not, and even if you’re asking instead when I’ll be bringing you ten million dollars that I keep saying you may already have won from the American Family Publishers, here’s the story of the birth of “Hi-yooo!” It may not be as memorable as “Don’t give up the ship,” but it does have more punch than “Tickets, please.”

One night in our seventh year, we had a terrible audience. That night, the studio had all the merriment of Grant’s Tomb. You may feel that performers shouldn’t blame an audience for a lack of response, but a show is a collaboration. Just before the opening night of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, a friend said, “Oscar, I hope the show is a success.” And Wilde replied, “The show is already a success. I hope the audience is.”

On this particular night, in our seventh year, the audience was failing and I felt they should have been made to stay after school and watch a repeat of the show.

Standing near me just off camera was our associate producer, John Carsey. Suddenly, John raised his fist and said, as a kind of rallying cry, “Hi-yooo!” as if he were not John Carsey but John Wayne putting the wagons in a circle. I had been considering a different cry, like “Wake up, you sluggards!” but John’s somehow felt even better and I cried it loudly to the semiconscious crowd. Instantly, they came alive and transformed themselves into a little bit of New Year’s Eve in Times Square.

From that night on, I sprinkled every show with a few “Hi-yooos!” Little did I realize when I dreamed of being in radio that I would bring to television a sound that might have been the last one heard by General Custer.