It was a happy coincidence that one of the guests on Johnny’s first Tonight Show was Groucho Marx, as if his torch were being passed to Johnny. Also on that first show were Joan Crawford and Rudy Vallee, two people who enriched the meaning of the word ego. But for ninety minutes, they were gently upstaged by a Puck from the prairie.

When the show was over, I sensed that we had a hit, but I wasn’t sure. For a moment, I wondered if I should go to Johnny’s dressing room, where everyone had gone; but then I decided not to and went home, where I soon learned that Johnny was America’s newest star.

And a little lightning had struck me too. The following day, one person after another came up to me and said, “Heeeeere’s Johnny!”

From the night of that first show to the last show thirty years later, Johnny never gave me a single piece of direction. At each show, in the few minutes before I went out to warm up the audience, he and I talked in his dressing room—about the news of the day and the stock market and our kids and the particular mental illness that made Dodger fans leave the ballpark in the seventh inning, even of a no-hitter. But we never talked about the show.

Those few minutes with Johnny were always an elixir for me.

No matter how sick I may have been—and I did the show with every kind of flu from Hong Kong to Jersey City—Johnny was a shot of adrenaline that both relaxed and recharged me.

JOHNNY’S GENIUS

It didn’t take long for Johnny’s genius to be revealed to America. Millions quickly learned how brilliant he was with an ad-lib, a saver, or a topper.

When Groucho Marx introduced Johnny on his first appearance on The Tonight Show, he passed his creative torch to Johnny.

In just the second year of the show, one of the guests was Ed Ames, who played Fess Parker’s Indian sidekick Mingo on the series Daniel Boone. Ed was proud of the way he had learned to throw an Indian tomahawk. In a dramatic demonstration, he faced the drawing of a man on a big piece of plywood, hurled the tomahawk, and hit the man in the worst place a man could be hit if he was interested in raising a family.

And then, Johnny turned to Ed Ames and said with sweet innocence, “I didn’t know you were Jewish.”

That line would have been impressive enough, but Johnny was flying. He waited until the precise moment that the laughter started to recede and said, “Welcome to frontier briss.”

After the cascading laughter had receded again, the embarrassed Ed Ames handed the tomahawk to Johnny, asking, “Want to try it, Johnny?”

And Johnny replied, “I couldn’t hurt him any more than you did.”

A triple that could only have come from him.

From the moment that Johnny took over The Tonight Show, I watched with awe as he pulled off savers and toppers never before seen on American TV. By our third year, audiences were almost rooting for him to bomb with a joke so they could savor Johnny’s long, quizzical look and then savor an ad-lib that was even better than the dearly departed delivery.

If all else failed—and it didn’t happen often—Johnny’s last resorts were a rubber chicken and an arrow-through-the-head that sat on a prop table beside him, the same sort of arrow Steve Martin had used to get easy laughs. Johnny knew that if the audience ever began to sound like one that was paying its last respects, he could pick up the rubber chicken or the arrow-through-the-head and get a laugh. He hated to go fowl hunting or arrow shooting, however, because such props lowered him to the level where laughs were sought with the comic elegance of whoopee cushions, squirting flowers, and lampshades on heads.

Johnny’s chicken rarely made an appearance because he had an unerring instinct for how to get a laugh. I never met a better judge of comedy or a more honest one.

One night, he began to read about six pages of jokes and it didn’t take long for us to know they were going nowhere. The audience was silently informing us that it was bombs away.

Suddenly, while Johnny still had a couple of pages in his hand, I picked up a lighter and set fire to them, a hot little memory from Who Do You Trust? My career, of course, also could have been going up in smoke. Johnny gave me one of his great long takes with his steely blue eyes and then grinned and said, à la Laurel and Hardy, “You’re absolutely right.” And then he threw the burning pages into the wastebasket while Doc Severinsen played Taps. There is no script for a moment like that.

On the very first program, October 1, 1962, Johnny and I were just beginning to figure out how to follow his fundamental philosophy for the show: “Don’t make it feel too planned” and “Just entertain the hell out of them.”

One night, in another burst of either courage or madness, I became more than a second banana—I became a champion’s second. That night, Johnny’s monologue was a tribute to the Eighth Air Force’s impressive low-level bombing. Johnny almost always had the unique ability to be funny about not being funny, to make good jokes about his bad ones, but not on this particular night.

I had done some bombing on my own, but tried to avoid it on the show. And so, unable to watch Johnny hunting for his first laugh and afraid he was about to break out in flop sweat, I suddenly walked over to him, grabbed him by the shoulders, and spun him around to face me. Never before had I walked into that forbidden zone where Johnny did his monologue on a star carved into the floor. But now I had to revive the star who was standing on it—and falling fast. I felt like a football coach trying to stiffen the spine of one of his men.

“Now listen to me, Johnny Carson!” I said. “Don’t let this audience get to you! It’s time they learned why they’re sitting out there and you’re standing up here. You’re funnier than they are! Even with the worst jokes, the ones you’ve been telling, you’re still the best, so now let it fly! Go back in there and get it done.”

I was telling him to win this one for our alma mater, NBC. To win one for the Gipper, even though the Gipper didn’t work there. And then, just in case he hadn’t been paying attention, I gave him a bracing slap on the face.

“Thanks! I needed that!” said Johnny as the audience roared.

“Now you’re with me,” Johnny said to them. “I have to get beaten up to amuse you. I was just beginning to think that you’re the kind of people who would give condoms to pandas—but now I’ll take that back. You’re the kind of people who would give sex advice to rabbits.”

The slapping of the star might not be funny today, but I did it in a time when there was a commercial for shaving lotion in which a gorgeous blonde gave a man a bracing slap on the face and he said, “Thanks! I needed that!”

It was lucky for me that, in this little play off a shaving commercial, I didn’t cut my own throat.

BACK INTO THE CAVE

People often ask me, “What was the funniest breakdown of a sketch on the show?” (Well, not that often. I think a guy in Toledo may have asked it, but I might have him confused with someone else.)

At any rate, there was one breakdown of a sketch that I will never forget, although I’ve tried to. In that sketch, Johnny was playing the oldest man in the world. Wearing a loincloth, with his hair askew, and carrying a club, he came out of a cave, where I greeted him. I had a clipboard in my hand and I was wearing a trench coat. Don’t ask me why. Don’t ask me why we did the whole sketch.

“I am standing here next to the oldest man in the world,” I said.

“Who’s that?” asked Johnny.

“That’s you.”

“Whatever.”

“So tell me, Oldest Man in the World . . .”

“My name is Mort.”

“Say, Mort, it just struck me . . .”

“Something should.”

“If you have a name, it must’ve been given to you by your father, who must have been older than you.”

“Yes, fathers usually are.”

“So you’re not the oldest man in the world.”

“And you’re not the best announcer in the world, or even in Burbank.”

“Tell me, Mort, did you know the Flintstones?”

“I think I met them once at temple.”

Well, temple was an appropriate reference because the studio audience sounded as if they were attending a memorial service. Johnny and I not only had entered the dumper, we had taken permanent residence there. Aware of this, perhaps because we were still awaiting our first laugh, Johnny suddenly turned and began walking away.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“I’m going to get out of this sketch,” he said, and he went back into the cave.

“Take me with you!” I cried and joined him in going from the dumper into the cave.

Johnny could have walked instead to his desk, beside which the small table always had those two small dumper-blockers—the rubber chicken and the arrow-through-the-head. However, because of his remarkable talent, that emergency hokeyness was almost never used. If you need a rubber chicken to get laughs, then your goose is cooked.

SWIT VS. SHARK

The best example I can remember of the two of us making a suit from whole cloth came on the night that Johnny said he had just learned something astounding about a small bird called the swit.

“I just saw a National Geographic show about the swit, and it’s absolutely astounding,” he said. “Are you aware that for the first three years of its life, the swit never stops flying? I mean, talk about your frequent fliers. This crazy bird eats in the air and mates in the air and has its babies in the air and—well, isn’t that incredible?”

“That’s fascinating,” I said, “but what about the shark?”

“The shark?” he replied. “What are you talking about?”

“Well, maybe the swit bird flies all the time, but eventually it lands somewhere and says, ‘Thank goodness that’s over; from now on, it’s Amtrak for me,’ but the shark never stops swimming. The water has to flow in and out of its gills, and if it stops swimming, it stops breathing and dies. So the swit is like a shark, only not really.”

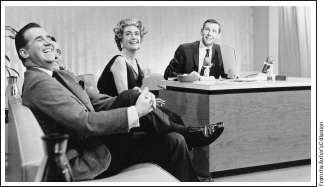

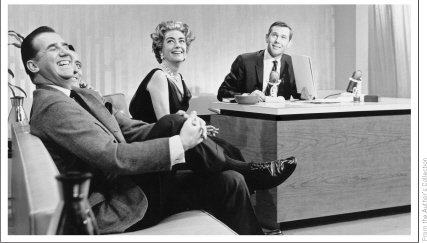

The guests on the first Tonight Show included not only Groucho Marx and Rudy Vallee, but also Tony Bennett (barely visible behind me) and Joan Crawford, smiling because she must be watching herself on the monitor.

“No, All Wet One,” Johnny said, “not just like a shark. The shark isn’t flying continuously for three years. You don’t have to be Peter Benchley to know that. Or even Peter Rabbit. You mean to tell me that at night the shark doesn’t stop and rest?”

“Now let me ask you: How would a shark know night from day?” I said. “Or, to put it another way, day from night? But there is a parallel, O Learned Ornithologist.”

“No, not a parallel or even a hexagon,” said Johnny, sending me his usual telepathic message that we should keep rolling as long as we could. “The bird can’t float—unless the birdbath is full of gin.”

“A Gordon bird.”

“That very species.”

“But much as I hate to correct you, O Birdman of NBC, O Prime Time Peacock, the continuous swimming of the shark is analogous to the continuous flight of the bird.”

Johnny paused and smiled at me as if to ask, How much longer can we do this crap before they replace us with The Three Stooges?

“No, Large Land Creature,” he said, “it is not analogous, whatever that means. It is easier to swim than to fly, except on Delta. The shark can actually stop swimming and do the dead man’s float in memory of his lunch.”

For another few seconds, Johnny and I rolled on and the laughs did too. He had said that he never wanted the show to feel too planned, and he certainly was getting his wish with this funny free fall in which neither of us had the slightest idea of where we were going—but how happy we were to be going there.

People often thought that from time to time, Johnny deliberately structured the monologue to bomb.

“They think I want to go down the toilet,” he told me. “But we work from the morning papers and sometimes the audience isn’t yet aware of what’s happened in the news. I guess I should base more jokes on the lottery numbers.”

Every morning over coffee, Johnny would go through the paper, marking stories that might be grist for the monologue. The Tonight Show both shaped and reflected American opinion because Johnny began every day making circles with a pencil. And he wasn’t picking horses.