Johnny was the greatest perfectionist I have ever known. Near the end of any show that he felt had not been excellent, he would say to me during a commercial, “Well, there’s always tomorrow.”

At other times during a commercial, he would become a TV critic and ask, “How much longer do you think we can get away with this?”

One night, during a commercial that followed a stillborn sketch, Johnny made my favorite off-air remark.

“Ed,” he said, “do you know When The Tonight Showy dream? I really want to become an aluminum siding salesman.”

The commercial just after the five spot was when Johnny often talked to me, sometimes dropping a bombshell. One night around 1970, he softly said, “You know, why don’t we move the show to California?”

“A great idea,” I said. “We’d have the best guests out there.”

“More important, the best weather for tennis.”

When The Tonight Show started, New York was the center of the entertainment industry. Rudy Tellez, an early producer of the show, remembers Johnny saying, “I’m never leaving New York. I love it.”

But in the early seventies, Fred de Cordova—Mr. Hollywood—had become the producer and wanted the show moved to California; more celebrities were available in California, and Johnny was enduring a bitter divorce struggle in New York. Johnny explained that “there’s not much television in New York anymore. When you do five shows every week for a year, it’s a little sticky sometimes to find a large number of lively people in New York.”

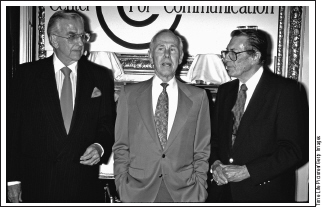

Johnny and myself with our masterful producer, Fred De Cordova, at a 1992 Communications Award ceremony honoring Johnny. A former film producer, Fred brought a disciplined intelligence to The Tonight Show.

And so in 1972 we moved to Burbank.

In Burbank, The Tonight Show aired from the studio that Bob Hope had used, and one Johnny liked. When we did the show in New York, we had used a converted radio studio that had only 250 seats. It was very small.

How small was it?

It was so small that when Dodge once demanded I use a real car in a commercial, we had to cut one in half and use only the front half; but the Burbank studio could fit a stretch limo. Johnny liked a big studio, and this one was so big that when he played the Jolly Green Giant, huge kernels of corn were able to fall as a sight gag. There were nights when I was expecting the arrival of other vegetables as well.

Bob Hope had insisted that the seats in that studio be steeply banked so the last row could be as close as possible and the laughs from it would be coming to him at the same time as those from the front. Johnny also wanted the audience to react as one unit, and not send him laughs in installments.

The audience certainly reacted as one unit when an elderly lady named Myrtle Young brought to Johnny her prize collection of potato chips, which had remarkable shapes. She had made the crispy shapes of such things as a beagle, a flower, and a candle.

Glancing at Johnny, I said, “Look at this one.”

“Oh yes,” she said, “it’s Yogi Bear.”

“Can’t these break?” I asked.

“They certainly can,” she said; and while she spoke to me with her eyes away from Johnny, he reached into a bowl of potato chips and chomped on one with the unmistakable sound of a chomped potato chip.

Myrtle Young looked at him as if she were seeing a Hitchcock film and she clutched her heart.

“I don’t think the nurse is on duty now,” I said, and then Johnny allowed her to breathe again by revealing that he had eaten a chip that belonged in no one’s collection. It was the kind of lovably impish thing he could spontaneously do better than anyone else.

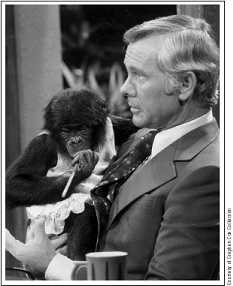

Johnny connected well not just with people of all ages and eccentricities, but also with other species, like the animals that Joan Embrey brought from the San Diego Zoo to the show: the gibbon, the goat, the baby kangaroo, the baby ape, the marmoset, and the chimpanzee. Johnny loved turning the show into his own Wild Kingdom, which inspired the wildness that often burst from him.

Johnny connected well not just with people, but also with other species, like the animals that Joan Embrey brought from the San Diego Zoo. Is the chimp holding a pencil to ease his nerves as Johnny did? Or does he have a new gag?

I’ve mentioned the unforgettable night when one of Joan Embrey’s baby leopards growled at Johnny and he decided to say good-bye to it, sprinted across the stage, and jumped into my arms. A hilarious moment, and so was the moment when one of Joan’s chimps preferred hugging Johnny to eating a banana. When I tried to pet the chimp, he pulled away. He wanted nothing to do with a second banana either.

Yes, the timing of Johnny’s reactions was always flawless: the sly grins and the long deadpan double takes that he learned from Jack Benny. I will never forget the look on Johnny’s face when one of Joan Embrey’s marmosets climbed up to his head and just sat there. He seemed to have been born knowing the funniest possible responses, both physical and verbal, to suddenly wearing a furry headpiece.

“Tell me one other place in this whole world of seven billion people,” he said, “where a man is sitting with a marmoset on his head.”

THE TAKE-NO-PRISONERSGENE

Whether in New York or California, this seemingly laid-back Nebraska boy drove himself like a Prussian general. In every enterprise, he was both a perfectionist and a fierce competitor. Not only did he want his show to be the very best, but he wanted to be the very best at every other activity too. It was a take-no-prisoners gene that came directly from his mother, an inheritance I discovered when he asked his parents to play poker with us.

After Johnny and I had played a state fair anywhere near his home, he invited his mother and father to come back to his hotel, and he didn’t want to look at baby pictures; he wanted to play killer poker. Johnny’s father was a gentle man, but his mother was a killer at cards; and so, she and Johnny played not like a Hallmark mother and son but like Mother Earp and Wyatt.

When Johnny made his memorable three jokes after Ed Ames had thrown his tomahawk at the most tender part of the target, Johnny let the laugh play and then he sharpened the tomahawk, eager to show how well he could throw it.

In everything Johnny did, he felt a compulsion to excel, a truth I learned one night at a cocktail party in Omaha, where I met people with past connections to him. One of the girls had dated him, one of the guys had boxed with him—and he wanted to be a knockout with both. When he went to Russia, he learned Russian; when he went to Africa, he learned Swahili. Some TV stars are still working on English.

As you know, Johnny finished every Tonight Show monologue with an easy golf swing. What delicious irony! On a vacation in Fort Lauderdale in November of 1962, after the show had been on the air for just a few weeks, Johnny played a round of golf at a country club the way so many people play—he stank. Luckily, however, while feeling his mind beginning to depart, he found relief at a water hole. He threw his clubs into it and was happy to see them disappear because it wasn’t a water hole, it was a lake.

Now aware that golf was a gift to man from Satan, Johnny vowed never to play again. The following day, he took up tennis; and because of his passion to excel, he didn’t merely play tennis, he strove for excellence, pouring his intensity into the sport to which he had turned because he was too intense for golf.

“ANYTHING YOU CAN DO, I CAN DO BETTER”

He was a Renaissance overachiever. One day on Who Do You Trust? an expert archer gave a demonstration, after which Johnny proudly shot the arrows just as well. He blended his passion for perfection with great athleticism, so he tried to top every guest expert on both shows: the karate expert, who showed him how to break a board with his head; the woman holding the hula hoop record, which Johnny tried to break with his slim lithe body; and the contortionist who tried to twist Johnny into a pretzel. He wanted to be the kind of pretzel that would make a Budweiser ad.

In fact, his passion to be the best caused an embarrassing moment on Who Do You Trust? An expert fisherman demonstrated fly casting and then Johnny topped the fisherman by fly casting with more accuracy. For Johnny, it was always that line from Annie Get Your Gun—“Anything you can do, I can do better.” I’m glad that the show never had a guest heart surgeon.

I remember Johnny spending an entire weekend in a hotel room to practice tricks for the show. More than just a magician, Johnny was also a ventriloquist who knew how to throw his voice. I knew how to throw mine, but it was always the same voice. He also taught himself how to play the guitar. He learned ballroom dancing and won an Arthur Murray jitterbug contest. In fact, Johnny was so competitive that when we went to state fairs, I had to act as his bodyguard in case he issued a challenge to the local middleweight champ.

Yes, life for Johnny was an endless salute to Vince Lombardi.