In the eulogies for Johnny after his death, many performers spoke of his rare class. None of them ever saw it as closely as I did.

One day when we were taping, he said to me during a commercial break, “Can I see you after the show?”

Well, I thought, this is it. He’s firing me, and I’ll have to start a new career. I wonder how the opportunities are in refrigeration repair?

On my way to his dressing room, I tried to figure out what I had done wrong. We always had worked so well together. Had he found someone with a louder laugh? Or someone who could hold “Heeeeere’s Johnny!” even longer?

When I entered the dressing room, Johnny lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply, and said, “Ed, I just want you to know that I know what you’re doing out there.”

Screwing up, right? Oh well, The Tonight Show would be a good credit on my résumé.

Instead of dropping the ax, however, he said, “You’re making me look good. You’re out there just to make me look good.”

A compliment from Johnny was rare. He presumed that everyone would do his job the way that Johnny did his—like a pro. Because my own nature is hearty, people don’t suspect that compliments have always made me as uneasy as they made Johnny.

“Johnny, I’ve got to go,” I said, hoping that my eyes wouldn’t grow moist. “I’ve got a dinner date.”

“Well,” he said, “I just want to tell you that I know exactly what you’re doing out there. You’re out there only to make me look good.”

No one, of course, had to make Johnny look good; he did that job splendidly alone. As I tried to flee from his moving words, he shouted, “You see, you can’t take a compliment any more than I can!”

Johnny, of course, was right: my role was to make him look good while not looking too good myself. My job as straight man, as sidekick, as second banana, was to get Johnny to the punch line while seeming to do nothing at all. Through the years, many people felt that on The Tonight Show, I did nothing at all. Their dismissal of my work was the highest flattery.

I’ve always liked the story about the straight man who was walking on a beach when he suddenly heard a woman screaming, “Help! Help! I’m drowning!”

“You mean to say you’re drowning?” he asked.

GENTLE HUMOR

What a thoroughly decent man Johnny Carson was. In thirty years of monologues, Johnny was careful never to hurt any person of whom he was making gentle fun.

I remember one show on which one of the guests was a woman whose talent, to use the word as loosely as it can be used, was to play coins by hitting them against a table to make sounds. When this woman came out, I was struck at once by how fat she was. She wore a pink dress that she not only filled but inflated. Some comics would have made an easy joke about her weight. Johnny, however, said with genuine warmth, “What a pretty dress.”

Bad taste makes a lot of money in America, but Johnny showed another way to go. He showed that it was possible for a man to be tender as well as funny.

After the show, I told him, “You were sweet with that woman who looked like a pink weather balloon.”

“A weather balloon?” he said. “She was the Hindenburg, but I wasn’t going to blow her up. When you’re three hundred pounds and come out in a pink dress to play coins, you’re not just asking for humiliation, you’re begging for it. Well, she wasn’t going to get any help from me.”

“Absolutely,” I said. “Too easy to mock a poor thing like that.”

“And cruel,” said Johnny.

“We do get an occasional circus act, don’t we?”

“The good ones are fine. But Ed, I’ll never understand why so many people are dying to humiliate themselves on TV.”

“Andy Warhol said everyone in America will be famous for fifteen minutes,” I said.

“They should be fifteen that don’t make you squirm.”

Through the years, Johnny felt that, like so many celebrities, he had made his own children squirm, and I might have done the same to mine. My daughter Claudia was once watching a dramatic space launch with friends; and then they suddenly saw something less celestial—Claudia’s father pitching beer.

Johnny, whose fame approached that of the president’s, was always aware of the effect of that fame on his kids. On the last show, he said to them, “I hope that through the years your old man hasn’t caused you too much discomfort.”

The kind of class Johnny had is a vanishing quality in American performers, who seem to enjoy flaunting obscenity, underwear, and small arms. Johnny himself talked about it on a show that was a sentimental journey to his hometown of Norfolk, Nebraska.

“I come from the Midwest,” he said, “and Midwestern values have always been important to me—openness, honesty, and a sense of warmth.”

I never did a film with Cary Grant, probably because he didn’t want the competition, but I did get to know Cary and had a few dinners with him. At every one, I asked him to come on The Tonight Show, but he always brushed off the request. Finally, at one of our dinners, I said, “Cary, you’ve just got to come on the show.”

“Ed, I simply can’t,” he replied.

“But why?”

“Because it would break the illusion.”

How much wiser was Cary Grant than today’s film stars, who share with the public glossies of their colonoscopies. Of course, you can’t break an illusion unless one is there to break. Johnny had the same wisdom about how his appeal was sustained by a certain separation from his fans.

“I do the show and then I go home,” he once told me, “but I don’t take it home with me.”

Like every viewer in America, I knew that Johnny wasn’t making hollow show business talk when he said on his last show, “It has been an honor and a privilege to come into your homes all these years to entertain you.”

And all of us felt his deep sincerity when, during his final applause and the strains of “I’ll Be Seeing You,” he mouthed “I love you” and threw a kiss. That kiss on the air was the first time a Hollywood air kiss had any meaning.

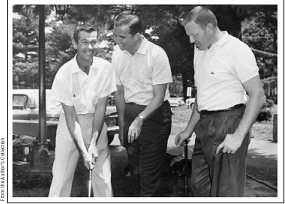

Before Johnny had his moment of truth in Fort Lauderdale and realized that golf was a gift from Satan, he and I tried to get a few tips from the great quarterback Sonny Jurgensen in Philadelphia.

Because Johnny had such high standards, he was upset the night that Tuesday Weld began behaving with a bit of arrogance. Johnny finally asked, “So tell me, what plans do you have for the future?”

And Tuesday replied, “I’ll let you know when I’m back on the show next year.”

“I haven’t scheduled you again quite that soon,” Johnny politely said, dispatching her with the lethal grace of Cyrano.

Of the twenty-two thousand guests who passed through The Tonight Show, Johnny fed all of them straight lines, appreciative laughter, and wit of his own. And once in a while, he graciously helped them get off.

I remember well a night when Peter O’Toole had come to us after forty-eight sleepless hours of filming and flying. The moment that Peter sat down, Johnny’s radar detected what he called “the dancing eye syndrome.” Seconds later, when O’Toole could not meet the challenge of speaking a complete English sentence, Johnny knew the man was in trouble and gently ushered him off the stage during the first commercial.

“I recognized the old syndrome at once,” Johnny told me after the show. “Peter’s eyeballs were twitching.”

“There were nights when you and I could have been ushered off too,” I said with a nostalgic smile.

“True,” said Johnny, “but thirty million people weren’t watching us at Sneaky Pete’s.”