twenty-five

When the Jokes

Were on Us

Without doubt, the party that Johnny disliked more than any other was not a real party, but a practical joke I pulled on him for my show, Bloopers and Practical Jokes, when Johnny and I were in London with Brandon Tartikoff, the head of NBC programming. Because Johnny liked Brandon, Brandon was able to lure him to a party supposedly filled with people worth meeting. These people, however, were actually minor English actors and worth meeting only if you found value in meeting minor English actors.

As he entered the cocktail party with me, Johnny asked, “Are these people really worth meeting? Or do they want to borrow money?”

“Johnny, they’re potential sponsors of the Wimbledon telecast,” I said, knowing the only thing they could sponsor would be a kid applying to Eton.

At the party, all the actors played as if auditioning for Oliver Twist. One by one, they talked to Johnny in accents so thick that Johnny was looking for an interpreter. Even spoken intelligibly, their words still would have been unintelligible.

“Old fellow,” said one of them to Johnny, “tosh blowsis arfing ah riss rowse viding wot brudderr. Isn’t that right, old chap?”

“You could put it that way,” said Johnny to a man who was making Buddy Hackett sound like Laurence Olivier.

“Ah, Carson, blessum ah tumley dumster posh pratter. Eh?” said another.

“There are those who feel that way,” said Johnny, wondering if he had fallen down the royal rabbit hole.

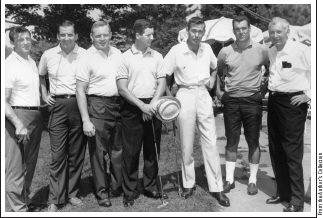

Johnny and I on a rare golf outing at a Philadelphia country club before we both gave up the insane game that is “a good walk spoiled.” Included in this group were Sonny Jurgensen (at my left) and Tom Brookshier (at Johnny’s left), both of whom played for the Philadelphia Eagles at the time.

And then, after hearing more of Her Majesty’s aliens, Johnny suddenly turned to me and said, “You’ll pay for this. And you’ll never know when.”

“Meet just one more. His name is Sir Gordon. Two grown men,” I said, shaking with laughter.

“No, only one,” said Johnny. “And one rotten child who reminds you that you’ll never know when.”

He had already decided to remember Brandon Tartikoff and me for having arranged this little joke. He couldn’t do anything to Brandon, but unfortunately I didn’t run NBC. And so, for me there would be a “when.”

“When” came a few weeks later in Burbank. After a taping, I left the NBC studio in a limousine driven by an old friend named Patrick. On the way to the gate, we passed a sign: “All cars are subject to inspection.”

A good idea, I thought. All cars should be inspected for impurities.

At the gate, we stopped and a guard told Patrick to open the trunk.

“Nothing in there but Jimmy Hoffa,” I called to him. He must have loved hearing car trunk gags.

When he opened the trunk, the guard didn’t find Jimmy Hoffa, but he found something worse: a huge collection of NBC equipment— typewriters, calculators, staplers, even a phone. The only thing missing was a peacock.

Putting his head in the car, Patrick said, “Mr. McMahon, he wants you to step out.”

“Oh, I can sign the autograph in here,” I said.

“No, there’s a lot of NBC property in the trunk, and I have no idea how it got there.”

As I sat there stunned and bewildered, someone else in uniform approached the car. I was so flustered that I didn’t recognize a guard named Johnny. He was wearing lieutenant’s bars. NBC security had taken him in grade as a transfer from the Navy.

“Would you like to call a lawyer or one of your English sponsors?” he asked.

Exploding with laughter, I said, “I’d like to ask Carnac how he got all that stuff in there.”

“By remembering the wonderful time Carnac had at a cockamamie cocktail party.”