twenty-nine

At Least Tonto Didn’t

Have to Keep Laughing

Of all the twenty-two thousand guests that Johnny had, the one with whom I most identified was Jay Silverheels, the Native American actor who played Tonto on The Lone Ranger. Of course, he never went out drinking with the Lone Ranger, but he might have played the drums. And in talking to Johnny, I never sounded like Cookie Monster. In those pre-PC days, Tonto did a lot of grunting. The only word he spoke that had more than one syllable was Kimosabe.

“So you were the Lone Ranger’s closest buddy for all those years,” said Johnny. “Sort of Ed with feathers. No, actually, Four Feathers were with Ed a lot.”

“Yes, I hung out with him,” said Jay Silverheels, “even though he was the stuffiest guy west of Newark. Man, did he take himself seriously!”

“He wasn’t a lot of laughs, was he?” said Johnny.

“You got that right.”

“And he kept sending you to town to get supplies. Why didn’t he ever go himself?”

“Maybe he thought the people in town didn’t like him. But I was the only one who didn’t like him. He never heard of the Emancipation Proclamation.”

“Yes, news traveled kinda slow out West.”

“And I washed his clothes and ironed his clothes and had to use all the damn bleach to keep his stuff so white. Twenty-five lousy years.”

“And he always wore that mask?”

“He did.”

“Tell me, did you ever get a look at his face?”

“Once. He let me peek under the mask.”

“And?”

“No big deal.”

“I think he saw too many Zorro films.”

THE HOMEWORK SCHOOL OF THE AIR

One of the most painful gags I can remember happened one night when we were doing the Homework School of the Air, which will never make the Comedy Hall of Fame, especially because there isn’t one. The star of the Homework School of the Air was, of course, Johnny, although on this particular night he probably wished it had been his worst enemy.

“And now,” I said, “a man who hasn’t let education go to his head, the dean and entire faculty of the Homework School of the Air, Professor John W. Carson.”

Don’t ask me why we thought Professor John W. Carson was funny. And don’t ask me anything else about the bit.

At any rate, out came Johnny in a cap and gown—his first mistake of the night.

“Professor,” I said, “our first question is from a woman in East St. Louis.”

“Why doesn’t she move to West St. Louis?” asked Johnny. “That’s the good side.”

“And let’s see if we can find the good side of this bit,” I said.

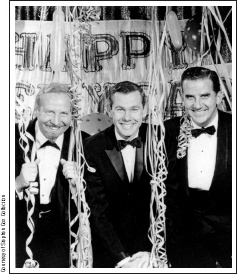

Skitch Henderson, Johnny, and me posing for the NBC calendar cover shortly after we started on The Tonight Show. The calendar was given to station affiliates, employees, and other friends of NBC.

“This woman would like to know, What is the most gullible animal?”

“What is the most gullible animal?” he asked, stalling for time until our flak jackets arrived.

“Yes,” I said, “I’m not changing the question.”

“The most gullible animal is the African mattayou.”

“What’s a mattayou?” I said.

“Nothing. What’s a matta you?”

The audience groaned. Kernels of corn should have fallen on us both.

“This audience would scalp tickets to a cockfight,” said Johnny, again the master of the rescue.

We should have mercifully ended the sketch right there, but something—stupidity, perhaps—moved us to show there were no depths to which we would not sink.

“You probably don’t know that I’m a music teacher,” said Professor Johnny.

“Is that germane?” I asked.

“Some of it is germane and some is Austrian. In fact, I’m tutoring a young lady in Austrian composers.”

“Mahler?” I said.

“Every chance I get.”

The audience topped its previous groan.

Moments later, during the commercial break, Johnny said to me, “We better not do stuff like that on the air.”

It was hard to remember that the man who had dropped those bombs was a perfectionist. On this forgettable night, the perfectionist must have been hoping for a tape delay—of a couple of years.

JACKIE REVERE

Johnny probably wanted a long tape delay on another night when a sketch was just as painful. Late in 1975, the Mighty Carson Art Players decided to either celebrate or desecrate America’s Bicentennial. In a sketch called “America’s First Comedian,” Johnny came out as a colonial stand-up comic, Jackie Revere. Well, it quickly turned out that Paul Revere had gotten more laughs when he cried, “The British are coming!”

“I rode my wife halfway to Lexington until I found out I was on the wrong nag,” Jackie Revere said, and there was respectful silence. “You know how I got the title Minuteman? On my honeymoon.”

There was continued silence from people who had first heard that joke in nursery school.

“But I’m surprised I hung around that long,” said Jackie Revere with the guts of Paul. “My wife is so ugly that she won a King George look-alike contest.”

Johnny was being as funny as King George.

Okay, Johnny, I thought, it’s another 911 call for you.

Hearing the call, he answered it by turning to the audience with a lingering look of puzzled innocence, a look that said, It’s not my fault; maybe it’s yours.

It was a look that would have made Jack Benny know that his legacy bloomed in Burbank. I wanted to help Johnny with the rescue, but there was no way I could get into the sketch because the entire solemn event was in costume. Finally, however, I got a cue.

“Philadelphia is so small,” said Jackie Revere, “that town drunk is an elective office.”

“Did someone mention my civic position?” I said. “Mr. Gordon ran my campaign for the job.”

“Ed, come on in and go down with us,” said Johnny. “Come and salute the Titanic.”

I don’t remember how we did it, but at last, as Johnny and I had done so often before, we became comic firemen who somehow managed to pull some laughs from the ashes.

Of course, like all entertainers who go before the public day after day, Johnny struggled with a maddening problem: he was competing with himself, and the better each show was, the harder it was to follow it with one just as good.

“There’s only one solution,” Johnny told me. “We have to be rotten from time to time to make our next ones look good.”

I never liked it when people told me, “The show was okay, but Tuesday’s was better.”

“Okay, we’ll stink tomorrow,” I wanted to say, “and then you can catch our comeback on Friday.”

Our opportunity for a comeback was never more inviting than after one Homework School of the Air that actually stopped the show, but not for the traditional reason. It stopped the show when Johnny discovered that my index cards with the questions didn’t match the answers he was getting from the cue cards behind the camera. Of course, this lack of synchronization could not have hurt a sketch that brought to mind a living will. In fact, giving answers to wrong questions might have been funnier than giving wrong answers to the questions that matched. Gum surgery also might have been funnier.

This sketch had been going down the drain when Johnny suddenly grabbed the index cards from my hand and began to look for a certain one that he felt had to be there. As he did so, I sat there in naked splendor, waiting for Johnny to save the moment with his wit. But for the first time I could ever remember, his wit was silent. He just kept going through the cards while I began wondering if this might be a good time to lie down in my dressing room. And it might have been if I’d had a dressing room.

This is the first dead air we’ve ever had on the show, I thought. And Johnny can’t resuscitate it because he’s busy doing research.

At last, however, he surfaced and said to the audience, “Ed may not quite be on top of what’s going on here. He just dropped in to get his mail between Star Search and his blooper show.”

This particular sketch wasn’t good enough for the blooper show.

Because Johnny was the best rebounder in the history of television, the show needed these lows to inspire his highs. He had another wonderful chance to bounce back after he had spoofed a Ronald Reagan press conference with a sketch that was almost good enough for a Rotary roast. Sometimes The Tonight Show’s writers were on target, but other times, it seemed that they deliberately wanted to challenge Johnny’s powers of recovery by giving him material that belonged in intensive care.

“Mr. President,” asked a reporter, “what is the state of our relations with China?”

“Well,” said Johnny as Reagan, “you know what happens: you have a peace talk with China and two hours later you’re at war again.”

Nothing could have been more challenging for Johnny than having to tell an ancient joke wrong. If you had to retell it, and I can think of no reason why, the retelling should have been “two hours later, you have to talk peace again.”

The writer who had descended to that subterranean level should have been sent directly to China—on a slow boat. I cringe remembering a few other lines.

“Mr. President,” asked the reporter, “have you any new appointments?”

“Yes,” said Johnny, “to see my barber at three o’clock.”

“And what came out of the last joint session of Congress?”

“We all got stoned.”

No proof of Johnny’s talent was more dramatic than his ability to somehow manage to get laughs during and right after material that would not have disturbed Yom Kippur or Lent.