Johnny,” I said a few months before he died, “we’ve had so many wonderful memories, both on and off the show, that nobody knows about.”

“We’d better keep it that way,” he said, “especially that night at Jilly’s when those two nutty . . . Of course, we didn’t do anything.”

“No, not that memory, but all the others. I’d love to share them with everyone in a book.”

“Well, you’re the only one to do it,” he said. “And you can do it anytime in the next century.”

“But so many people . . .”

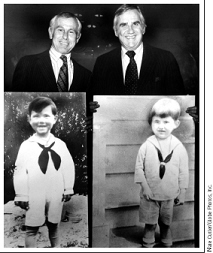

Our childhood photos reveal that from middy blouses to blue suits, both Johnny and I avoided maturity along the way.

“Ed, write A Boy’s Life of Wayne Newton first. Or The Wit and Wisdom of Fats Domino. Or the story of the Lincoln Tunnel: For Whom the Tolls. Or . . .”

“Stop!” I said, laughing hard. “Johnny, there are so many worthless books being published.”

“And you want to write another one? Hey, how about writing The Joy of Zinc for all the people who find romance in minerals?”

“Seriously, Johnny,” I said, “every day a dozen people ask me, ‘What’s Johnny Carson really like?’”

“The same dozen? Well, just tell them the truth. I’m an easygoing sociopath whose hobbies are bungee jumping, collecting swimsuit pictures of Jack LaLanne, and doing Zen meditation with P. Diddy. We pray for a new name for him.”

TOO SOON

My heart breaks to think that I do not have to wait until the year 2100 to write my memories of Johnny Carson. At a few minutes after seven o’clock on the morning of January 23, 2005, the telephone rang in my Beverly Hills house. My wife, Pam, answered it and her hand fell to her heart. As the blood drained from her face, she silently handed the phone to me. I didn’t need Sherlock Holmes to know what had happened.

“Johnny,” I said.

Pam’s look said it all. In dismay, I took the phone.

“Ed,” said Johnny’s nephew, Jeff Sotzing, “Johnny just died.”

“Oh, no, no.”

“You’re my first call. He would have wanted me to call you first. I know how much you two meant to each other.”

Being at a loss for words isn’t my style, but it was then.

“Jeff . . . I . . . I don’t know what to say.”

“You don’t have to.”

“I’m reeling now. Let me call you back.”

Then I started to cry—the first tears that Pam ever saw me shed.

The following day, I just lay in bed, watching all the tributes to Johnny, crying one minute, laughing the next. It was a style of mourning you don’t often see.

“Ed,” I can hear Johnny saying, “you needed a grief counselor. Or maybe one for volleyball. ”

In the following weeks, I went on many radio and TV shows, on each of them paying tribute to Johnny. And one day, his widow, Alexis, called.

“Ed,” she said, “I’ve seen everything you’ve done. You’ve been magnificent.”

“Johnny would’ve hated it all,” I said.

“Yes, wouldn’t he? But it’s so wonderful you’re doing it. I love you, Ed, just as Johnny did.”

FRIENDS

Skitch Henderson once said that I treated everyone with love, an observation that made me sound more like a captain in the Salvation Army instead of a colonel in the U.S. Marines. Well, I haven’t always treated everyone with love. In 1952, I dropped several unloving things on some North Koreans. But I always felt a little extra love for Johnny, who dropped a few bombs of his own when we were together.

Most comic teams are not good friends or even friends at all. Laurel and Hardy didn’t hang out together, Abbott and Costello weren’t best of friends, and Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis—well, there were warmer feelings between Custer and Sitting Bull. However, Johnny and I were the happy exception. Although he was my boss, we shared the unwavering affection of a couple of equals who drove themselves to work, finally found the right wives, and liked to lose themselves in drumming and singing while listening to jazz.

For forty-six years, Johnny and I were as close as two non-married people can be. And if he heard me say that, he might say, “Ed, I always felt you were my insignificant other.”

On his farewell show, I was deeply moved when Johnny told America, “This show would have been impossible to do without Ed.

An early publicity photo showed that we enjoyed working together.

Some of the best things we’ve done on the show have just been . . . well, he starts something, I start something . . . Ed has been a rock for thirty years and we’ve been friends for thirty-four. A lot of people who work together on television don’t like each other, but Ed and I have been good friends. You can’t fake that on TV.”

No, you can’t. George Burns said, “In show business, the most important thing is sincerity. And if you can fake that, you’ve got it made.” However, there was no faking what Johnny and I felt for each other.

Every year on our anniversary show, October 1, Johnny would turn to me and say, “I wouldn’t be sitting in this chair for [fill in a number from two to thirty] years if it weren’t for this man beside me. He’s my rock.”

My booming laugh on The Tonight Show was never just a conditioned reflex, but always a genuine appreciation for the man who could come up with something like: “A woman was arrested out here in Los Angeles for trading sex not for money but for spaghetti dinners. Would that make her a pastatute?”

That line came from Johnny, not one of his writers, none of whom had wit that approached his.

On another night, Madeline Kahn and Johnny were talking about their fears. “Anything particular that you’re afraid of?” he asked her.

“Well, it’s strange, Johnny,” she said, “but I don’t like balls coming toward me.” “That’s called testaphobia,” Johnny said.

Johnny always managed to come up with just the right line, or just the right gesture, or a blend of both.

ICE WATER?

“Johnny Carson has ice water in his veins,” some people used to say.

To which Johnny once replied, “That’s just not true; I had all the ice water removed. I did it in Denmark many years ago.”

He also had a less comic reply: “Ed, I’m so tired of the same old crap: people telling me, ‘You’re cool and aloof.’ They always want to know why I’m cool and aloof instead of hot and stooped. You’ve known me for eighteen years. Am I cool and aloof?”

“No, my lord.”

Johnny had developed the reputation for being cold and aloof because he was uncomfortable with people he didn’t know, but I knew him better than anyone outside of his family, and I can tell you there was never any ice water to remove. In July of 1995, when my son Michael died at forty-four from stomach cancer, Johnny called me with just the right words. And after speaking those words, he said, “There’s not a day when you won’t think of him.”

Ice water? When his own son Rick was killed in a car crash in 1991, Johnny gave a short, moving eulogy that let America know what flowed in his veins.

“I’m not doing this to be mawkish, believe me,” he said as he showed a picture of Rick and then some of Rick’s nature photographs. “Rick was an exuberant young man, fun to be around. And he tried so hard to please. You’ll have to forgive a father’s pride in these pictures.”

The final one was a sunset.

And America knew that warm flow again on the next to last Tonight Show, when Bette Midler sang to Johnny and his eyes moistened on hearing “You Made Me Love You” and “One for My Baby and One More for the Road.”

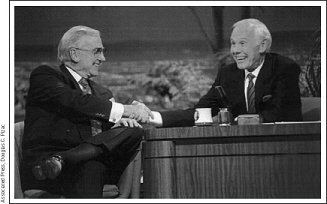

May 22, 1992, was the last of nearly five thousand times that Johnny and I sat on opposite sides of the desk on The Tonight Show.

That was one of the very few times I saw Johnny tearful. I can remember only three others: at Jack Benny’s funeral; when Alex Haley, the author of Roots, gave Johnny a leather-bound volume titled Roots of Johnny Carson—A Tribute to a Great American Entertainer with the inscription, “With warm wishes to you and your family from the family of Kunta Kinte” on the flyleaf; and when Jimmy Stewart read “I’ll Never Forget a Dog Named Beau,” a poem about his golden retriever. The poem was forgettable, but Johnny was moved by the way Jimmy Stewart delivered it. Jimmy was a blend of great actor and great person. Both Johnny and I were in tears. Just a couple of maudlin mutt mourners.

ACHINGLY MISSED

I don’t think I will ever be able to accept that Johnny is gone. His favorite song, “I’ll Be Seeing You,” is hard for me to hear now, much harder than hearing Stevie Wonder sing it to Johnny on one of the last shows. So often I look at a phone with a sinking feeling because I can’t pick it up and get to him.

“And well you know that sinking feeling,” Johnny would say, “from all the nights we went into the tank. ”

Johnny Carson is achingly missed. The critic James Wolcott described him as “cool, unflappable, precise, Carson always knew how to pivot. He was comedy’s blue diamond, the master practitioner, the model of excellence.”

Yes, blue diamond, this large rhinestone remembers well how you pivoted with all those guests who suddenly made you dance with them. You weren’t Fred Astaire, but you weren’t Fred Mertz either. You danced endearingly one night with Pearl Bailey to “Love Is Here to Stay,” moving with an airy blend of comedy and grace. You danced courageously with Vlasta, the international queen of polka, who easily could have made you look like someone falling down stairs. And the night I watched you rhumba with that fat woman from Detroit, looking funny but not foolish, never mocking her but sweeping her along with that same airy blend, I wondered, Is there nothing this man can’t do?

For more than three decades, we performed together on two television shows and at road shows, conventions, and state fairs. We read each other so well that either of us could launch a bit and the other would know where to take it. When a dog in one of my Alpo commercials walked away from the food instead of eating it, Johnny knew how to jump right in. On all fours, he crawled over to the food bowl and became TV’s first animal understudy.

When Johnny said that one of Joan Embrey’s chimps was seven or eight years old and I said, “No, Johnny, I think he’s nine,” we looked at each other and were off on another flight from an unlikely launching pad.

“Let me get this straight, Ed,” said Johnny, tapping the pencil he often held. “You’re correcting me about the age of a chimp?”

“Sorry, Johnny,” I said, playing it just as straight, “but a man has got to have standards. You start with faking the age of chimps and then you fake elephants and the next thing you know, you’re five years younger yourself. You just work your way up.”

“Or down.”

“Yes, that’s certainly another way to look at it.”

“Ed, you studied philosophy in college and maybe even learned a little. In the grand scheme of things, how important is the age of a chimp?”

“Well, maybe not important to Plato,” I said.

“Right. Plato had hamsters.”

“But you’ll have to admit it’s certainly important to the chimp.”

“Eight, nine . . . he’s too young to drive anyway.”

“But not for certain theme park rides, if the cutoff is nine and not eight.”

“I have a theme park ride in mind for you, Ed. The half-built roller coaster.”

WHAT WAS JOHNNY REALLY LIKE?

Since Johnny’s death, every national magazine except Cattleman’s Quarterly has been telling things about him that small children already knew. Well, I’m going to tell you some things that neither small children nor large adults know. Here, with Johnny’s nervous blessing, is my answer to the question that almost drove this second banana bananas: What was Johnny really like? And as I spin these memories, I’ll be hearing him say, “Easy on the bull, Ed, or I’ll find a way to have Carnac let everyone know that the Marine Corps issued you a security blanket.”

On his last show, Johnny read this line from a letter: “Now we’ll see if Ed McMahon really thinks you’re funny.”

A cute line. But for anyone seriously wondering if I were the world’s greatest actor for thirty-four years, these pages contain the resounding answer.