two

Good-bye,

Mr. Philadelphia

Television

Johnny came to New York from a CBS show in Los Angeles called The Johnny Carson Show, which was canceled after thirty-nine weeks. Its producer, a man named Brady, said, “Johnny Carson isn’t a strong voice. He just can’t do stand-up comedy.” It couldn’t have been an easy thing to do, but Mr. Brady managed to overlook what was already an impressive comic talent. He must have been related to the Hollywood producer who saw Fred Astaire’s screen test and said, “Can’t sing, can’t act—dances a little.”

A former carnival barker, boardwalk pitchman, and Marine Corps pilot in World War II and Korea, I had come from broadcasting at Philadelphia’s WCAU, a show so deep in TV’s prehistoric age that its eleven o’clock news ended at nine fifteen. The station then became a night-light until the next morning for a city that W. C. Fields saluted on his tombstone with the words: I’d rather be in Philadelphia.

It was 1958, and unlike Mr. Brady, the programmers at ABC saw enough in Johnny Carson to make him the host of a daytime game show called Who Do You Trust? And one of them saw enough in me to suggest me as an announcer to Johnny. My road to Johnny was long and full of detours and potholes. It led from the boardwalk in Atlantic City, where I sold Morris Metric Slicers; through carnivals, where I boomed enticements for strange acts; and it even took me door-to-door selling pots and pans.

Heeeeere’s stainless steel!

EARLY REHEARSALS

I began to prepare for my life with Johnny when I was eight years old. I did more than just lie on a rug and dream of microphones. I turned my grandmother’s parlor into a studio where I did my own shows. Those were the golden days of American radio, when the announcers had rich, full voices fit for pulpits. In my boyish voice, I announced everything from the sinking of the Titanic to the rising of the sun. And I knew how to introduce, tease, or sum up every fifteen-minute adventure serial on the air.

People who came into the house were startled by the boyish cries:

From out of the night comes Bulldog Drummond! . . . Have you tried Wheaties? . . . Heigh-ho, Silver, away! . . . This is a job for . . . Superman! . . . Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows! . . . Jack Armstrong, the all-American boy! . . . L-A-V-A, L-A-V-A . . . I have a lady in the balcony, Doctor . . . Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. North and South America and all the ships at sea. Let’s go to press! Flash! Ed McMahon got hit by another nun today!

To my parents, my dream of being a radio announcer was merely a whim, but not to the boy who even announced, “Good morning, Bayonne. It’ll be sunny and mild in Hudson County today. There’s a twenty-minute delay at the Lincoln Tunnel, fifteen-minute at the Holland, and a great view from the George Washington Bridge. Adolf Hitler just took over Germany.”

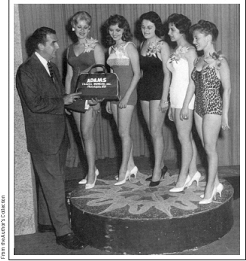

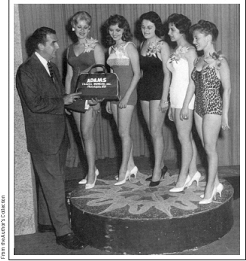

As host of the Miss Philadelphia Contest for the Miss Universe Pageant, I always looked for intellectual depth. Once I almost found it.

At seventeen, I had my first job in radio, but I also prepared for Johnny by working as a bingo announcer at carnivals. “Here’s the winner—Fannie Schmertz! Come up here, Fannie, and get your forty dollars! Where are you from, dear? Jersey City? What a glamorous place that is!”

My unwavering dream was to be America’s greatest radio announcer. I never dreamed, of course, that “I have a lady in the balcony” was rehearsal for feeding El Moldo. And that “Heigh-ho, Silver!” was a prelude to “Hi-yooo!”

“PHILADELPHIA’S MR. TELEVISION”

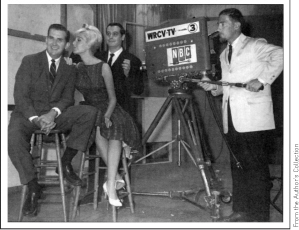

Philadelphians saw more than enough of me in the fifties. In 1952, I had thirteen shows. I was host of the late-night movie, starred on a game show, and did spots on the news. I also had a show called Strictly for the Girls and played a clown on a Saturday morning circus show called The Big Top.

McMahon and Company was one of my thirteen Philadelphia television shows. In Philly I did everything but air traffic control.

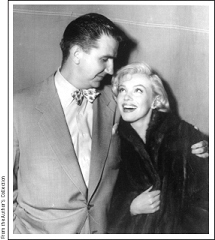

When I met Marilyn Monroe on the set of How to Marry a Millionaire, she told me, “You know, Ed, I don’t have anything on under this.” But, of course, I saw right through that.

Yes, I did everything on local television but describe the traffic on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. The magazine that would become TV Guide called me “Philadelphia’s Mr. Television.” Of course, W. C. Fields would have said, “Being Philadelphia’s Mr. Television is almost as great an honor as being Newark’s Mr. Mail.”

And then the Marine Corps recalled me and sent me to Korea. My recall was a double jeopardy faced by many reserve officers who were transferred from warm beds to cold mountains after North Korea decided that five years of peace were too many. Ensign Johnny Carson, who dreamed of becoming a professional magician, was lucky—there was less need in combat for men who knew how to make the three of spades disappear.

During World War II, I served my first tour of duty in the Marines, learning how to fly and then teaching flying and carrier landing to others, including some of Pappy Boyington’s pilots, who went on to lead the famous Black Sheep squadron. Now the Marines were asking me back to see an exotic Asian land and for a chance to get killed there. I put on my uniform again, bought some life insurance, and flew into the unfriendly North Korean skies. New “critics” were gunning for me now—and they hadn’t seen any of my shows. It was my great fortune that all of them missed during the eighty-five combat missions I flew.

I returned from Korea to a heartwarming welcome. All thirteen of my shows had been canceled. And so, every morning, I took the eight o’clock train to New York, where I went into my office—a Penn Station phone booth—took out a five dollar roll of dimes and index cards, and called agents, talent scouts, and producers to try to get a TV audition. On most days, after not getting one, I took an early train back to Philadelphia for my only TV work—a five-minute commentary at the end of the local nightly news. Regular commuters knew how my day had gone. If I took the 4:30 Congressional back, an audition had opened for me. Most days, however, I took an earlier train back to Philadelphia to keep dreaming the seemingly impossible dream.