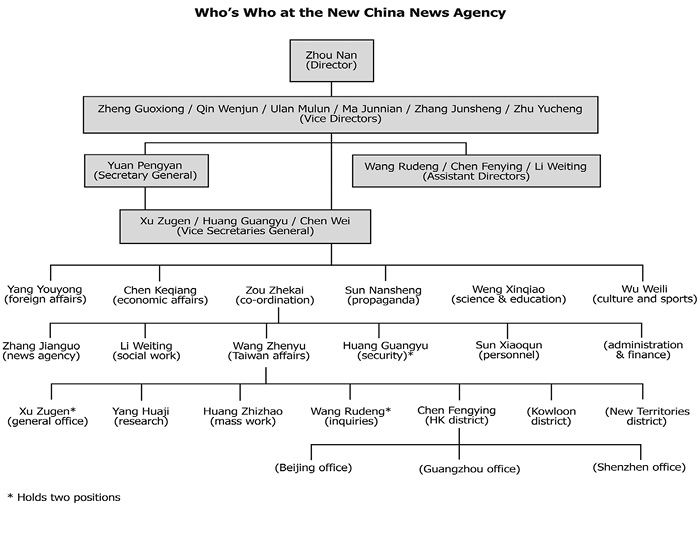

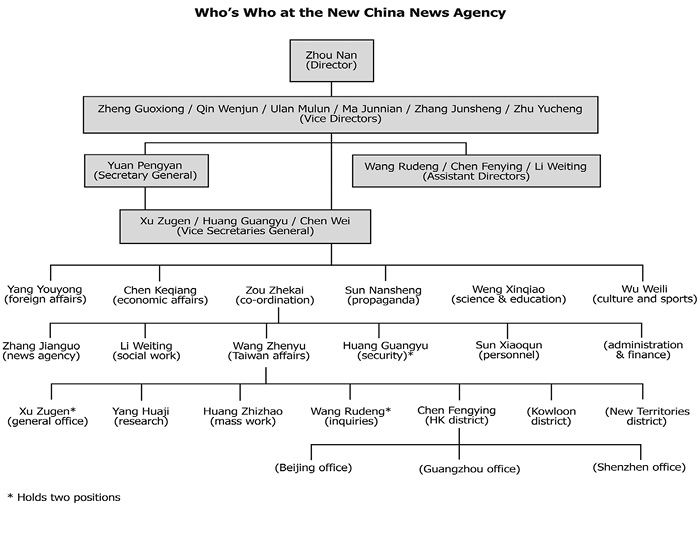

Figure 6 Xinhua Organisation under Zhou Nan24

The Chinese Communist Party wanted to ensure that the future Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government would be able to function without interference from subversive or unfriendly forces and for Beijing to be able to exert control should it be necessary. This outcome could only be assured if post-1997 power remains in the hands of patriots. A structure designed for control had to be put in place during the final years of colonial rule. The people who would work the system also had to be made ready. Once these were bolted down, Beijing could feel comfortable enough not to be seen to intervene after the transfer of sovereignty. The CCP referred to this as the zhuada concept (hold a firm grip on major things), and once this had been secured, it could tolerate minor things (fangxiao),1 such as a few opposition legislators.

The final few years before reunification required the CCP to anticipate and deal with potential British “treachery”. The threat to a smooth transition was the new British push for greater democracy after the events of Tiananmen. It was what the British needed to do to be able to leave Hong Kong with honour in the eyes of international opinion. There would be many conflicts between the British and the Chinese as they tried to achieve their respective goals. Although the CCP was ready to counter British efforts, the party could not have anticipated that it would have to deal with a new governor quite different from any of his predecessors. Beijing reserved the harshest criticisms for him.

Breaking off relations was not an appealing or workable option for either side because they needed each other to make the moment of the Reunification (for the Chinese) and the Handover (for the British) a confident affair. Although at one time, the Chinese had thought momentarily that the British and Chinese could each have their own ceremonies and it would be obvious to the world which one was more important.2 Whatever the Chinese thought of the British, one country, two systems could not be allowed to fail since it was for China to implement and realise. The eyes of the world would be on Hong Kong. Macao would come back to the fold in 1999, and there was still the big prize of reunification with Taiwan in the future.

The CCP knew it needed to strengthen the post-1997 establishment that would serve the HKSAR, including producing the first HKSAR chief executive and appointing suitable members of the first Executive Council. To be on the safe side, the party also started to create a fifth column of Mainland foot soldiers in Hong Kong to protect Beijing’s interests, especially during election time.

Post-Tiananmen Doubts

The Hong Kong community was devastated and drastically transformed by 4 June. The events were:

so dramatic that it drew around the clock coverage by Hong Kong mass media, so emotional that it ignited the nationalistic feeling of many Hong Kong Chinese, so appealing that it rekindled the democratic aspiration of the local populace, and so tragic that it made most of the Hong Kong people moan, weep, and thunder.3

The CCP saw things quite differently, as was made clear by Ji Pengfei on 22 June:

The counter-revolutionary riot in Beijing started out first as a student movement and later as turmoil. During this time Hong Kong compatriots expressed their different viewpoints in various manner. Some Hong Kong people went to the mainland and were involved in activities prohibited by the state constitution and law; in effect they provoked more riots. [Hong Kong should not] interfere or attempt to change the socialist system on the mainland. Nor should they allow some people to use Hong Kong as a base to subvert the people’s government.4

In the aftermath of 4 June 1989, Beijing had many challenges, one of which was the struggle for political authority to succeed the aging leadership led by Deng Xiaoping. Holding tightly onto power at the party centre was essential to riding through the storm. The issue of a smooth transition for Hong Kong to Chinese rule became embroiled in that struggle. Toughness had to be displayed, as softness might have given the British and the Western powers the mistaken impression that CCP rule was vulnerable. Thus, those who showed sympathy to the demonstrators had to be purged, the most senior of whom was Zhao Ziyang, the general secretary of the CCP. He was expelled from the Standing Committee of the Politburo and put under house arrest for the rest of his life until his death in January 2005.5 With Deng Xiaoping’s blessing, Jiang Zemin, the then party secretary of Shanghai and a Politburo member, replaced Zhao, and eventually assumed the posts of the general secretary of the CCP, chairman of the Central Military Commission and president of the People’s Republic of China. Jiang would stay in power as China’s top leader until 2002.

Beyond the succession challenge and economic sanctions from the West imposed after 1989, Beijing had to deal with its pariah status in the world, the implications of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, as well as the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe. In assessing world affairs, the CCP adopted a cautious and watchful outlook on foreign relations.6 An early remedial effort by the CCP to mend its reputation was to use every attraction and sweetener to invite international guests and businessmen to visit Beijing in order to give the new leadership the appearance of acceptance. This was particularly important for Li Peng, who more than anyone else was seen to have been most associated with the implementation of the crackdown.7

Invitations were extended to Hong Kong business people to visit Beijing and meet top leaders. T. S. Lo was a most willing traveller there. He met Li Peng, which made him a man to note back in Hong Kong, as he might be heading for greater prominence since a post-1997 leader had to be identified and made ready to assume power.8

Crisis of Confidence

Hong Kong’s despondency could be seen from the nervousness of even the tycoons and taipans.9 Xu Jiatun disclosed an interesting twist to the post-Tiananmen saga. In a move to stave off control of Hong Kong by China in 1997, a group of Hong Kong’s richest businessmen led by Helmut Sohmen, the Austrian son-in-law of shipping magnate Pao Yue Kong, tried to set up a plan to pay Beijing HK$10 billion to lease the territory for ten years from 1997 and for it to practise self-rule. Xu thought they were naïve and told them that there was a slim chance that the idea would be acceptable to the Chinese leadership, but he would pass it on nevertheless, but they had better not publicise it. After Jiang Zemin had become the general party secretary in June 1989, he interviewed Xu and supposedly asked Xu to send a report to him and Deng Xiaoping elaborating on the tycoons’ idea. Jiang would eventually turn the proposal down. Lu Ping and Zhou Nan criticised Xu for sending the report, describing it as a move on Xu’s part to seek power and wealth by selling the country.10

Xu must have faced a horrendous grilling by party officials for not having controlled the situation in Hong Kong. For example, the Wen Wei Po wrote unhelpful editorials. Long-time left-wing supporters, such as unionists Cheng Yiu Tong and Tam Yiu Chung, participated in marches. Worse, employees of Xinhua Hong Kong published a letter calling for Li Peng to step down.11 For Xu, the head of the CCP in Hong Kong, to have allowed such acts was unforgivable.

Beijing was concerned that Hong Kong people might become difficult to deal with. Some of the Hong Kong BLDC members petitioned Beijing for a delay in the resumption of sovereignty and for the British to continue in administration. This was regarded as a top secret according to Lu Ping. Obviously, if the petition became public, it could gather steam and would put enormous pressure on Beijing. Lu sought the view of Jiang Zemin, who response was: “It is nothing. Stand firm. Don’t let it happen.”12 On 11 July 1989, when Jiang Zemin met the leading figures of the BLDC and the BLCC, he used the opportunity to issue a warning to Hong Kong people—they should not interfere with Mainland politics—“the well water should not interfere with the river water”.

Xu Jiatun knew that he did not have the trust of Jiang Zemin and Li Peng, as he had with Zhao Ziyang. Indeed, a reason he did not have the new leaders’ trust was that he was considered too close to the deposed Zhao. According to former Xinhua deputy director, Huang Wenfang, Jiang and Li had taken over the handling of Hong Kong matters at the CPP Central Committee level with the help of Qian Qichen, who was foreign minister from 1988 to 1998. Matters of importance relating to the colony were first reported to Qian, and then Jiang and Li would be asked for their advice. The two top leaders divided Hong Kong work between them: Li handled most of the issues concerning government departments, while Jiang handled party affairs and decisions concerning overall decisions.13

Xu realised that his days in Hong Kong were numbered. Indeed, he was seen by Li Peng as part of the Zhao Ziyang faction—a definite disadvantage for Xu Jiatun in those difficult days following the Tiananmen crackdown.14 In order to minimise the fallout, he asked that he be allowed to retire. On 15 January 1990, Beijing announced that Zhou Nan would replace Xu as the new director of Xinhua Hong Kong. Xu remembered events thus:

[After retirement] I had intended to stay in Shenzhen. When it was made clear to me that Zhou had set up a special team to investigate me, I woke up to the real purpose of Mr Zhou’s appointment. He was going to make me the whipping boy. I therefore decided to leave [China]. I called a friend in Hong Kong to come to see me in Shenzhen. I asked him to apply for a US visa for me in Hong Kong. The then US consul-general wondered whether it was true. It took a few days for them to issue a visa for me. I came to Hong Kong from Shenzhen by car and went to the airport. When I arrived, the Hong Kong government had made special arrangements for me to board the flight.15

Xu believed that he was facing an imminent purge and fled to the United States with three family members in May 1990. He passed away in Los Angeles in 2016. Beijing considered Xu’s defection as traitorous because his escape was seen to have been assisted by Western forces to which Xu was prepared to disclose state secrets.16 In March 1991, he was stripped of his party membership for “deserting the people”. There must have been bad blood between Xu and his three colleagues—Lu Ping, Li Hou, and Zhou Nan. While he accused them of deceiving Beijing into thinking that Hong Kong people welcomed the reunification,17 they saw Xu as disloyal. Xu Jiatun and Zhou Nan would continue to spar verbally even in 2007, when they reflected on the past. Zhou accused Xu of defecting to the United States with his mistress. Xu countered that the party had never been able to prove what he did wrong.18

Zhou Nan arrived in Hong Kong in February 1990 to take up the post of director at Xinhua Hong Kong. He was a vice minister at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and had led the Chinese team in the reunification negotiations. The status of CCP Hong Kong was changed—it no longer carried provincial level status as it did under Xu’s leadership. Unlike during Xu’s tenure, when Deng Xiaoping and Zhao Ziyang were willing to decentralise power to CCP Hong Kong, Jiang Zemin’s priority was to recentralise authority.

Some saw the power of initiating and formulating policy on Hong Kong going to the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office.19 However, in 1994 Huang Wenfang made a point of clarifying the flow of authority, two years after he retired from Xinhua Hong Kong. He stressed that Xinhua Hong Kong and the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office were of equal status, both at ministerial level and that neither had leadership over the other. Xinhua was a top-level overseas post of the CCP, while the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office was a government office of the State Council handling Hong Kong and Macao work. Huang explained that a top-level party post meant that firstly, Xinhua Hong Kong was set up and controlled by the party; secondly, it represented and was responsible for the party’s work that fell within its scope; and finally, it was the CCP’s top organ in Hong Kong. When there was an important decision to be made about Hong Kong policy, CCP Hong Kong and the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office would meet and discuss it. If the issue concerned Sino-British relations, someone from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would also join the discussion. If it concerned some other issue, such as an economic matter, then people from the relevant departments would join. Huang felt it was necessary to make this clarification because the media often referred to the Mainland’s work relating to Hong Kong as a “three horse carriage” linking Xinhua Hong Kong, the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, and the Hong Kong and Macao desk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He also wanted to clarify that leadership over important decisions related to Hong Kong were made by top party leaders—Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, and Qian Qichen—not the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office at the State Council or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.20

There was one issue however on which Zhou Nan followed in the footsteps of Xu Jiatun, that was to significantly expand the workforce within Xinhua Hong Kong. In 1983, shortly after Xu arrived in Hong Kong to take up his post, he had wanted to increase the number of staff to about 600. By the time he left, the size had increased from about 150 people to 400 people. During Zhou Nan’s time by 1997, the workforce grew to 600 people.21 (See Figure 6.) However, between 1990 when Zhou first took over Xinhua Hong Kong and August 1992, 180 middle- and low-ranking staff members were transferred back to the Mainland chiefly because of their participation in Tiananmen-related protests and parades in Hong Kong.22

Compromise on Political Reform

As a result of the massive crisis of confidence in Hong Kong as the events of 1989 unfolded, there was strong public sentiment that a faster pace of democratic reform was essential to guarantee the autonomy of the future political system. Even prior to the crackdown on 4 June,23 there was an ongoing debate within the BLDC, the BLCC and Hong Kong society about the design of the future political structure. As noted in Chapter 8, the OMELCO Consensus model, proposed in May 1989 by the members of the Executive and Legislative Councils, though popular in Hong Kong, was unacceptable to Beijing. The Group of 89 and the more liberal members within the BLCC proposed the new “4–4–2 model” that they thought was “pro–Hong Kong” and might be more acceptable to Beijing.

Figure 6 Xinhua Organisation under Zhou Nan24

They also worked with the liberal wing among Hong Kong’s opinion leaders at the time so that there could be wider agreement on what the future political model should be. This scheme provided for 40 percent of the seats in the Legislative Council to be directly elected, and the rest would be divided between functional constituencies (40 percent) and an electoral college (20 percent) from 1995 to 2001. Chinese officials rejected the 4–4–2 model.25

Beijing preferred T. S. Lo’s bicameral model. This called for the legislature to be made up of a district and a functional chamber. For the first and second terms of office, members of the district chamber would be elected by District Boards and Municipal Councils, while the functional chamber would be selected by occupational groups. In the third term, legislators would decide whether the legislature’s composition should be changed. There would be a split voting system for different categories of legislators. Members of the two chambers would vote as two separate blocks. All bills would need to be passed by both blocks to succeed. Lo’s ideas of creating a split voting system in the legislature found its way into Annex II (II) of the Basic Law. Thus, while the post-1997 legislature is one house, it functions like a bicameral body where the directly elected members could be constrained.26

The initial momentum created by the OMELCO Consensus and the efforts of the Group of 89 dissipated. In time, the business community focussed on calling upon the British Government to grant British nationality to Hong Kong people instead of pushing for a much faster pace of democratisation.27 Many of them were keen to both be on good terms with Beijing, as well as to obtain foreign passports as an insurance policy should they need to decamp from Hong Kong.

The events in Beijing from April to June 1989 greatly affected world opinion on Hong Kong’s future. Britain could not be seen to be acting honourably and responsibly if it did not provide arrangements to guarantee “a high degree of autonomy” in post-1997 Hong Kong through Hong Kong people electing their own political leaders. Soon after the crackdown, British foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe wrote to Vice Premier Wu Xueqian stating that confidence in Hong Kong had been badly shaken, and that Britain was planning to reconsider the arrangements for the direct elections of 1991 in Hong Kong. Howe also asked Beijing to postpone the passing of the Basic Law. The Chinese reply marked the start of a long diplomatic row—China would not agree to any change concerning Hong Kong’s political system by Britain.

The CCP’s Conspiracy Theory

The CCP’s assessment of Hong Kong in terms of world politics concluded that Britain had changed her policy towards China with respect to Hong Kong and the British were prepared to use Hong Kong to destabilise the CCP regime. From Zhou Nan’s recollection, which reflected the dominant CCP’s view at the time, Hong Kong was no longer a matter between China and Britain. It had become a plot organised by Western anti-China forces. For example, he considered Margaret Thatcher’s call in October 1989 to the member states of the Commonwealth to “state unequivocally its support for Hong Kong and call on China to rebuild confidence there”28 as an attempt to ask for international efforts to intervene in Hong Kong affairs.29 Qian Qichen’s reflection was more elegantly expressed. He thought Britain “considered that it had made excessive concessions over Hong Kong, and it wanted to regain lost ground”.30

The CCP regarded the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China to have been an instrument of the anti-China forces. The fear was that the West would use Hong Kong as a subversive base against China. A crucial change after 1990 to CCP Hong Kong’s united front policy under Zhou Nan was that it became much less inclusive. Pro-democracy groups and those of more liberal persuasion were excluded.31

It did not help that most of the leaders of the pro-democracy camp, such as Martin Lee and Szeto Wah, were key members of the Alliance, which had actively supported the student demonstrations in Beijing in 1989, and helped to smuggle many of the wanted activists out of the Mainland after the crackdown. The Alliance was branded a subversive group, and Martin Lee and Szeto Wah as subversives. Although Lee and Szeto had already resigned from the BLDC, they were formally expelled. A new provision was introduced to the draft post-1997 constitution to prohibit treason, sedition, secession, subversion, and theft of state secrets so as to strengthen Beijing’s ability to control events in the future. The HKSAR government’s attempt to legislate what Article 23 of the Basic Law requires would cause a massive demonstration in Hong Kong in 2003 that would change the CCP’s policy towards Hong Kong once more (Chapter 10).

Hong Kong Pre-1997 Political Parties Formation

1989: Hong Kong Democratic Foundation

1990: United Democrats of Hong Kong

1990: Liberal Democratic Foundation

1992: Co-operative Resources Group, which became the Liberal Party in 1993

1992: Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong (DAB)

1994: Hong Kong Progressive Alliance (merged with the DAB in 2005)

There is one aspect of Article 23 worth noting. It also includes a provision that requires the HKSAR to pass legislation “to prohibit foreign political organisations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organisations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organisations or bodies”.32 While the Basic Law does not have a provision specifically about political parties, Article 23 tacitly acknowledges that political parties can exist but is specific that they must not have ties with foreign political bodies or organisations. This is to make it plain that Hong Kong parties must not have ties with hostile foreign forces.

In December 1989, Percy Cradock—who was by then Margaret Thatcher’s special policy adviser—went to Beijing to deliver a long letter from the British prime minister to Jiang Zemin. The letter stated that Britain would follow the Sino-British Joint Declaration, had no intention to use Hong Kong as a base of subversion or to internationalise the question of Hong Kong. However, Britain was facing huge pressure to “increase substantially” the quota of directly elected legislators in 1991, pressure that could not be ignored. Thatcher expressed a hope that China would keep in step with Britain’s arrangement when drafting the Basic Law. When Jiang met Cradock, the Chinese understood the British wanted elections in Hong Kong to be a precondition for putting Sino-British relations back on track. Jiang warned that the Chinese were not oblivious to what the West was thinking:

In addition to domestic factors, the international environment also contributed to the political turmoil that happened in late spring and early summer in China this year. On the international stage, some people misinterpreted the situation. They believed that various socialist countries had become chaotic enough that China too would collapse with a push.33

As for public opinion in Hong Kong, Beijing suspected British manipulation. Jiang commented that:

As for public opinion, we have to find out if the views are being manipulated or genuinely expressed by the people. In Western countries, the so-called public opinion and the ruling power’s “guidance” and intention are always closely related. Some people in Hong Kong believe they are representing public views, but I cannot agree with them. Those people either have their own agendas or they simply want to make trouble.34

Crisis of Legitimacy

Subsequent to the meeting between Jiang Zemin and Percy Cradock, Cradock also met China’s foreign minister, Qian Qichen, to whom he gave a letter from the new British foreign minister, Douglas Hurd, detailing the British positions of the draft Basic Law. Qian saw Hurd’s letter as evidence that the British had indeed changed its stance on Hong Kong. He recounted that there had been smooth cooperation between the two countries in drafting the Basic Law and the British had no objections to the first published draft but now the British were raising considerable disagreements, “especially the developments of Hong Kong’s political system, and added more requirements, such as increasing drastically the proportion of directly elected members in the Hong Kong Legislative Council”.35

Beijing believed the British were taking advantage of the negative international sentiments against China post-Tiananmen to push for a more rapid pace of democratic reform in Hong Kong. To put in place a representative government in Hong Kong was seen as unnecessary and part of a ploy to strike at China.36 The British were seen to be attempting to change Hong Kong’s longstanding executive-led political system, where power was focussed in the hands of the executive to a legislative-led one, so as to restrain the executive by enhancing the power and status of the legislature. The purpose of such a ploy was to transform the post-1997 Hong Kong into an “independent entity” in order to serve Britain’s long-term political and economic interests.37

Despite strained relations and mutual distrust, China and Britain continued to negotiate. Qian Qichen and Douglas Hurd corresponded on Hong Kong’s democratic reform arrangements over a series of seven letters. By February 1990, the two sides had reached a secret agreement as a result of Governor David Wilson’s visit to Beijing and his meeting with Li Peng, where Wilson managed to persuade Beijing that without significant advance on direct election, Hong Kong would become ungovernable. The agreement reached was that the British would provide for 18 directly elected seats in 1991 to the Legislative Council (30 percent of total seats) using the “double seat, double vote” system, and in return, Beijing agreed that there would be 20 directly elected seats in 1997, 24 seats in 1999 and 30 seats in 2003. That voting system meant there would be double seat constituencies and voters could cast two votes for each of the seats.38 This method was used to reduce the chance for the pro-democracy groups to sweep all the seats if a single-member system was adopted instead. If the arrangements were satisfactorily implemented, those elected to the Legislative Council in 1995 could ride on a through train and serve until 1999. That arrangement was enacted in Annex II (I) of the Basic Law promulgated in April 1990 by making an exception of the arrangements for the first legislature after 1997. In the end, it was Sino-British agreement that proved to be more important than the efforts of the BLDC and BLCC. The Sino-British through train agreement represented the best compromise that could be reached by the two sides.

Shoring Up Confidence amidst Suspicions

To shore up confidence in Hong Kong, the British government announced the British Nationality Scheme in December 1989, which offered 225,000 people or 50,000 qualified households in Hong Kong the right of permanent residency in Britain. As stated by Governor David Wilson, the purpose of the scheme was to “give those selected the confidence to stay in Hong Kong up to and beyond 1997”.39 Britain also asked other countries such as Australia and Canada to devise similar emigration scheme for Hong Kong people. From the CCP’s point of view, rather than anchoring the people to stay, the scheme was a ploy to “internationalise” Hong Kong with the hidden agenda of turning Hong Kong Chinese into nationals of other countries.40 In response, Beijing claimed that the scheme violated the Sino-British Joint Declaration and declared that it would not recognise such passport holders as foreign nationals. Thus, China would treat them as Chinese nationals within Chinese jurisdiction. Furthermore, Beijing inserted a provision into the Basic Law that the post-1997 Legislative Council shall be composed of Chinese citizens who are permanent residents of the Region with no right of abode in any foreign country. However, permanent residents of the Region who are not of Chinese nationality or who have the right of abode in foreign countries may also be elected members of the Legislative Council, provided that the proportion of such members does not exceed 20 percent of the total membership of the Council.41 The 20 percent would go to specific functional constituencies, such as the those representing the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce and Tourism, as a concession to businessmen and professionals, some of whom held foreign nationality or had right of abode overseas.

In October 1989, Governor David Wilson also announced a massive infrastructure project referred to as the Port and Airport Development Strategy. The whole project would cost HK$127 billion and the first phase, which included the building of a new airport on Lantau Island, was scheduled to be completed in 1997. Announcing the project in his Annual Policy Address that year, Wilson said that: “despite the shocks we have experienced during the year, your Government is continuing to plan for the long-term future of Hong Kong. We have a clear vision of what we are trying to achieve. It is a vision that I hope will sustain Hong Kong during the present period of uncertainty and give us all confidence in our ability to overcome whatever problems confront us.”42 The British saw the new airport project as a way to instil confidence. The British and Hong Kong authorities had not expected problems because Chinese officials had voiced no objections in private briefings. Moreover, the Bank of China had also publicly welcomed the project immediately after its announcement and Xinhua Hong Kong even published the Bank of China’s suggestion that the Land Fund could be used to fund the airport.43 Thus, the decision on the part of Beijing to denounce the project was astonishing. Governor David Wilson recalled events thus:

We had told the Chinese what we were going to do at several levels but as it came at a time when all high-level contact had been broken by the European Union, frankly I don’t think anything was registered . . . the Chinese became highly suspicious of us, egged on, I fear to say, by some of their supporters in Hong Kong.44

The Chinese claimed that it would deplete Hong Kong’s fiscal reserves and the British would give out all the contracts to their favoured parties.45 Hence, Jiang Zemin publicly criticised the project as a British plot to “host an extravagant meal and leave China to pay for it”.46 Though Beijing also recognised that Hong Kong needed a new airport, it effectively blocked the project by refusing to give an undertaking on behalf of the future HKSAR government to repay loans. This strategy forced an agreement with the British that Britain and China would form a consultative body and the Hong Kong government would leave not less than HK$25 billion in reserves for the post-1997 government. In September 1991, John Major (prime minister, 1990–1997) flew to Beijing to sign the Memorandum of Understanding for the project with Li Peng.47

The controversy over the airport enabled Beijing to achieve its objective of having a say over pre-1997 affairs in Hong Kong. As early as January 1991, Beijing had wanted to find a way to assert itself. Wu Xueqian made the remark that “during the transition period, only the Central People’s Government can, and is entitled to, speak on behalf of the people of Hong Kong”.48 In April 1992, Lu Ping, by then the head of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, made Beijing’s intention very clear:

In the latter half of the transition period, the Chinese government does not intend to intervene with the administrative affairs of the British-Hong Kong government. However, for matters related to the 1997 issue and smooth political transition, which require the future SAR government to bear responsibilities and obligations, the British-Hong Kong government should consult more often with the Chinese government. The Chinese government has the responsibility to consider and participate in examining these matters. This practice is entirely consistent with the spirit of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. In the latter half of the transition period, if the British-Hong Kong government cannot obtain the support of the Chinese government, some matters would be very difficult to be accomplished.49

Indeed, from 1991, Chinese officials including those at Xinhua Hong Kong began to comment more frequently on Hong Kong affairs. For example, Xinhua Hong Kong objected to the proposed privatisation plan of Radio and Television Hong Kong, the public broadcaster. In 1991, after the landslide victory of the democratic camp in the first ever Legislative Council election with a number of directly elected seats, Beijing warned the Hong Kong government not to appoint any democrats to the Executive Council.50 In March 1992, Lu Ping expressed concern that the Hong Kong government budget planned to raise taxes to pay for increased expenditure, and in Lu’s view, this was against the principle of spending to be kept within revenue stated in the Basic Law.51

The Surprising Chris Patten

In 1992, John Major decided that David Wilson should step down as governor of Hong Kong. Major neither named a successor nor arranged another diplomatic posting for Wilson, who had another three years before he was to retire. Major also removed Percy Cradock as foreign policy adviser. To some observers, these personnel changes signalled that the British government was unhappy with its two most important experts on Hong Kong and how Sino-British affairs were proceeding.52 What was a total surprise was the eventual appointment of Christopher Patten as the last governor of Hong Kong.

Chris Patten was a heavyweight in British politics, which gave him a special authority with the British political establishment. He was after all the chairman of the Conservative Party, who had just had the party re-elected. While he charted the party’s re-election victory in 1992, he lost his own seat in the constituency of Bath and thus had to leave Parliament. Patten’s appointment as governor of Hong Kong was an accident of history. His seniority and close relationship with John Major and Douglas Hurd gave him direct access to them to discuss Hong Kong matters. Patten arrived in Hong Kong in July 1992 and created a sense of curiosity all round, since Hong Kong had never had a politician as head of government. He knew his job was to ensure Britain could exit the colony and be considered by world opinion to have done its best for the people of Hong Kong.

During the earliest weeks of his governorship, Patten took measure of his closest advisers in the Executive Council. Lydia Dunn, the most senior member then, persuaded all the other members to offer their resignations in order to give the new governor a chance to restructure his cabinet. He took the opportunity not to reappoint some of the members. Rita Fan, Selina Chow, and Allen Lee were not invited back. They would become fierce opponents to Chris Patten, but would continue to enjoy long political careers in Hong Kong, including appointments to the NPC. Rita Fan would achieve the highest accolades post-1997. In March 2008, she was made one of the vice-chairmen of the SCNPC—a highly sought-after position. Most interesting, Patten added Tung Chee Hwa, a shipping tycoon to the Executive Council. Tung was in fact Beijing’s nominee, and thus represented the voice of political conservatism and also that of Beijing.53 It is unclear exactly when Beijing decided Tung was its choice for the HKSAR’s first chief executive, but he was obviously already a contender in 1992. One report noted that by late 1995, Tung had become the top choice after a period of background checks by the Mainland security and political apparatus.54

Without anyone knowing what he would do at the time, Patten was going to surprise Hong Kong—and Beijing—with his first Policy Address in October 1992. Patten exploited grey areas and found room in the Basic Law to introduce more democratic elements in the system. Patten insisted that:

What I have tried to do with these proposals is to meet two objectives which I understand represent the views of the community—to extend democracy while working within the Basic Law. All the proposals I have outlined would, I believe, be compatible with the provisions of the Basic Law. What these arrangements should give us, therefore, is a ‘through train’ of democracy running on the tracks laid down by the Basic Law.55

The Patten Proposals had seven elements:

1. Using of the “single seat, single vote” method for all three tiers of geographical constituency elections to the District Boards, Municipal Councils56 and Legislative Council;

2. Lowering of the minimum voting age from 21 to 18;

3. Abolishing all appointed seats on the District Boards and Municipal Councils;

4. Removing the restrictions on local delegates to China’s NPC to stand for elections;

5. Broadening the franchise of certain existing functional constituencies by replacing corporate voting with individual voting;

6. Introducing nine new functional constituency seats; and

7. Introducing of an Election Committee comprising of District Board members to return 10 members to the Legislative Council.57

A fortnight prior to the announcement, Douglas Hurd had given the details of the Patten Proposals to Qian Qichen. The Chinese side warned that in their view, some aspects of the plan were in violation of the Basic Law, and a legislature so elected would not be able to straddle across from 1997 to 1999. They emphasised that any arrangements for the 1995 Legislative Council election should be agreed by both side beforehand. Beijing saw the Patten Proposals as direct confrontation. To the Chinese, Patten had ignored the Seven Diplomatic Documents between Qian and Hurd, about which amazingly the Foreign Office had not briefed him. In other words, it had inexplicably withheld the information.58

Beijing made Patten the principal culprit of the trouble and the Chinese propaganda machine singled him out for attack. Lu Ping labelled Patten as “Sinner of a Thousand Years” at a press conference.59 In Hong Kong, Xinhua officials used many occasions to criticise Patten. For example, Zheng Guoxiong, Xinhua Hong Kong’s deputy director, said that:

Patten insisted on confrontation by putting forward his reform proposals. This affected and harmed the prosperity of Hong Kong. Chris Patten did not have any sincerity to cooperate with China. His attitude was thoroughly confrontational, Chris Patten completely ignored the effort and attitude of the Chinese government and he brought harmful effects to the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong. He should be the one who bears all the responsibility.60

CCP Hong Kong’s strategy was to galvanise Hong Kong people to oppose Patten and his reform package, and to persuade the people that China, not Britain, was the real protector of their long-term interests. Zhou Nan, in meeting with the chairmen of the District Boards, said that:

More and more Hong Kong people have realised that Patten’s political reform package is in serious violation of the Joint Declaration, the Basic Law and the previous agreements reached by Chinese and Britain. They also realised that by walking along this wrong path, Patten has already jeopardised and will continue to jeopardise the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and a smooth transition. We have already taken and shall take all the necessary measures to maintain the stability and prosperity of Hong Kong, to ensure a smooth transition in 1997 and to protect the long-term interests of Hong Kong people. The only way out for Patten is he should immediately abandon his so-called political reform package and stop playing political tricks.61

It is interesting to speculate whether Chris Patten would have acted differently had he known about the seven diplomatic exchanges. Perhaps the packaging would be different, but the substance could well have been much the same because the totality of the Patten Proposals was in fact quite modest. The Chinese side appeared to have been so upset with the last governor that perhaps they saw the expert packaging for more than what it was.62 Chris Patten had to be publicly humiliated whenever possible to show China would not bow to pressure. Thus, on one famous occasion in December 1993, Zhou Nan refused to shake Patten’s hand at a public event.63 In Beijing’s view, the fight over Hong Kong’s political system related to the integrity of Chinese sovereignty and China had to be tough.64 However, the crudeness and rudeness did not go down well with the people of Hong Kong or in world opinion. Patten understood that if he submitted to Beijing’s pressure, he would no longer have the credibility and authority to govern Hong Kong in the remaining years before 1997. For many Hong Kong people, while they may not have believed Patten’s way could change Beijing’s mind, they still saw him as a champion for their cause. After all, there were not many people who could say no to Beijing.65 According to the polls conducted by the Public Opinion Programme of Hong Kong University, Patten enjoyed high popularity ratings throughout his tenure in Hong Kong.66

In February 1993, Britain’s foreign minister Douglas Hurd wrote to Qian Qichen for proposing negotiation “without preconditions”. In March 1993, the Hong Kong government published Patten’s political reform package in the official government gazette. On 22 April 1993, the two sides reached a decision that negotiations between them would start in Beijing. Jiang Enzhu, the deputy foreign minister, represented the Chinese side, and Robin McLaren, the British ambassador to China, represented the British side. Patten played an all important role in controlling the content of the negotiations. The two sides held seventeen rounds of talks on the arrangements for the 1994 District Boards and 1995 Legislative Council elections but were not able to reach agreement. Beijing blamed Britain for breaking off the talks.67 Jiang Enzhu would become ambassador to London in 1995, and director of Xinhua Hong Kong from 1997 to 2000 before becoming the director of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong until 2002.

On 30 November, negotiations effectively came to an end when Douglas Hurd wrote to Qian Qichen that the British had decided to present the Patten Proposals to the Hong Kong Legislative Council for scrutiny. The Chinese saw that as “a declaration of a showdown with China”.68 Qian’s reply was that it was a matter of principle to China that the opinions of the Hong Kong legislature could not supersede the discussion between the two governments and that if the British did indeed put the Patten Proposals to the legislature it would mean a breakdown in bilateral negotiations.

With the tabling of the Electoral Provisions (Miscellaneous Amendments) (No. 2) Bill 1993 (giving effect to the first four proposed reforms) and the Legislative Council (Electoral Provisions) (Amendment) Bill 1994 (giving effect to the last three proposed reforms) in the Legislative Council, CCP Hong Kong’s role was to do its best to torpedo them. It was a close call for Chris Patten, but the two bills were passed on 24 February 1994 and 30 June 1994 respectively. Beijing made it clear that the last District Councils, the Urban Council, the Regional Council and the Legislative Council would be terminated with the expiration of British administration. The through train would not run and Beijing would organise matters separately.

Overt Route to Taking Charge

In preparing for the resumption of sovereignty, Beijing had to cultivate individuals and groups in Hong Kong to become part of the post-colonial establishment under Chinese rule. In light of the deteriorating relationship with the British since 1989, and especially after the arrival of Chris Patten, the CCP had to do its best to counter British interest to promote political reform, derail the Patten Proposals, and put in place a shadow government to undermine the colonial authorities after the passage of the proposals.

Since Xu Jiatun’s time, CCP Hong Kong had already begun to institutionalise the co-option mechanism by first focussing on the capitalist class to bring them onside in the belief that the business elites were the most crucial in maintaining prosperity. As many of the leading business people were already members of the political elite through appointments by the British into the colonial structure, the CCP’s strategy was to win them over by giving them a place in the post-colonial establishment. As Xu had observed, businessmen were pragmatic and their first concern was always their business interests. The Hong Kong appointees to the BLDC and BLCC reflected the party’s successful effort to recruit large numbers of influential business people. As noted in Chapter 8 and above, some of these voices cultivated by the Chinese side proved most useful in resisting demands for more liberal reforms, as shown by Louis Cha’s mainstream model, and T. S. Lo’s bicameral model. Moreover, appointments to the BLDC and BLCC provided useful experience for the CCP in working with the business elites and other opinion shapers. Indeed, from those appointments, many of the individuals have gone on to occupy important positions in post-colonial politics, and even their sons and daughters.

Local affairs advisers

Nevertheless, it was necessary for CCP Hong Kong to further expand its reach in the Hong Kong community after the promulgation of the Basic Law and to strengthen its ability to counter the British pursuit of political reform post-Tiananmen. Implementing an idea from Lu Ping, China created general honorific advisory positions in order to outreach to a larger number of people. Between March 1992 and April 1995, a total of 186 people were appointed for two years as Hong Kong affairs advisors in four batches. The appointments were given much fanfare by the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office and Xinhua Hong Kong. These advisors were appointed on individual basis and mainly consisted of prominent businessmen, pro-Beijing politicians and professionals, academics and labour union leaders.69 Tung Chee Hwa, who would become the first chief executive of HKSAR, was appointed as one of the first batch of 44 advisors along with other tycoons like Henry Fok, T. K. Ann, Run Run Shaw, and Li Ka Shing. No one from the democratic camp was appointed. The Chinese officials emphasised that the appointment of these advisors was to “build a regular channel of communication with Hong Kong people and gather the wisdom of Hong Kong people” and they would not “undermine the administrative capacity of the Hong Kong government” nor “be a second power centre”.70 There was no formal work for the advisers. Another 667 district affairs advisers were appointed to bring in less important people who had influence within a narrower sphere such as District Board chairmen and Municipal Council members.71 Indeed, expanding its network would have been in China’s interest whatever the state of Sino-British relations. These appointments had endorsement value, being of individuals who had respectable records of public service but who would not engage in the confrontations over democratic reforms that had occurred on the BLCC.72

Preparing for elections

The CCP was prepared to be pragmatic. While it was not in favour of a faster pace for elections, once it became clear that an election was going to occur, the party begun to mobilise pro-China groups to take part. The appointment of district affairs advisers was an important step in fighting district elections. The CCP would need to find suitable people to stand for election, as well as people in the districts to drum up support. At the same time, CCP Hong Kong had actively to establish its power base at the grassroots level, cultivating relationships with such people as the leaders of kaifongs, mutual aid and area committees, members of District Boards, members of the Heung Yee Kuk, as well as urban councillors and regional councillors. To fight legislative elections, it needed to encourage both the grassroots leaders and the elites to form political parties and stand for direct and functional elections. Moreover, the party would also need to strengthen its traditional bases with left-wing trade unions, women’s groups, youth groups and other satellite united front organs to mobilise support during campaigning. Examples of newer united front groups included the Federation of Women which was inaugurated in 1993 with 600 members with legislator and CPPCC delegate Peggy Lam as the chairperson, the Association of Chinese Enterprises (an organisation made up of Mainland companies in Hong Kong), the Association of Post-Secondary Students (a patriotic student union), and the Federation for the Stability of Hong Kong (made up of various politicians and Hong Kong affairs advisers, district affairs advisers, NPC and CPPCC deputies).73

There was a flurry of activities among the younger members of the political elites to face upcoming elections. Maria Tam was the chairperson of the Liberal Democratic Federation. T. S. Lo founded the New Hong Kong Alliance, but it never got very far as Lo realised he would not become the first chief executive. A group of legislators formed the Co-operative Resources Group in 1992, which eventually morphed into the Liberal Party.74 Tsang Yok Shing founded the DAB in 1992 with Tam Yiu Chung also becoming a member. Since the DAB was the pro-Beijing party, its role was to check the pro-democracy parties in elections prior to 1997, support the policies of the HKSAR government post-reunification, and act as a united front umbrella within the Hong Kong community.75 When it was felt that the DAB was too grassroots and a middle-class pro-China party was needed, solicitor Ambrose Lau was encouraged by Xinhua Hong Kong to form the Hong Kong Progressive Alliance in 1994 through the merging of various groups that had heavier business and professional memberships.76 While Maria Tam’s party never got very far, she eventually joined the Hong Kong Progressive Alliance, and when that folded into the DAB in 2005 after its lacklustre performance in the 2004 legislative election, she became one of the DAB’s vice-chairmen. The functional electoral system also ensured that the left-wing camp would win a number of seats through its allies in various functional constituencies, such as labour, and the Heung Yee Kuk.

In election campaigns, CCP Hong Kong functioned as a “behind-the-scene commander, orchestrating the co-ordination of pro-China candidates and mobilising satellite organisations”.77 In order to prepare for the 1994 District Board elections and the 1995 Legislative Council elections, Huang Zhizhao, the deputy secretary-general of Xinhua Hong Kong was given the responsibility of coordinating the fielding of candidates, and there was also a working group within Xinhua Hong Kong led by Zheng Guoxiong responsible for mapping out long-term strategies for its favoured candidates and groups in future elections.78

Subsequent to the 1994 and 1995 elections, the election machinery would continue to expand to include the Federation of Hong Kong–Guangdong Community Organisations, Kowloon Federation of Associations and Hong Kong Island Federation. The older New Territories Association of Societies had already been established in 1985 and going forward, these bodies would play important coordination roles in election campaigns to assist the patriotic camp. Taking the Hong Kong Island Federation as an example, it has a number of affiliated organisations, including the Unified Associations of Central and Western District, Unified Associations of Wanchai District, Unified Associations of Eastern District, and Unified Associations of Southern District. These affiliates would play active roles as well in mobilising yet other affiliated groups and their members to vote for patriotic candidates and parties.79

Up until today, the united front organs and their satellites implement top down, pyramid-like, mobilisation for the DAB or specific candidates the CCP supports by spreading messages of support to every corner of the networks. The satellites embedded in the community are like transmission belts for these messages to flow through. Moreover, the large united front organs, such as the FTU, also provide people and money to assist in campaigning. To ensure these organs work hard for the preferred parties and candidates, there are overlapping memberships between the DAB and the united front organs (Chapter 10 and Figure 7). For example, DAB leaders such as Tam Yiu Chung and Cheng Yiu Tong are long-time leaders in the FTU, and the DAB has also invited district leaders to join the party. For example, former legislator and District Councillor Chan Kam Lam represented the Kwun Tong Residents’ Union, and District Councillor Suen Kai Cheong was once the leader of the Wanchai Federation of Associations.80 The party also acts as mediator to reduce competition and conflicts among the parties and groups.81

Preliminary Working Committee

On 16 July 1993, just as the first two batches of Hong Kong Affairs Advisers had been appointed, and in the midst of the Sino-British row over the Patten Proposals, Beijing decided to create yet another body called the Preliminary Working Committee. The intention to form the committee was first made known publicly in March 1993. However, it seemed Beijing already thought some such body was necessary in order to prepare for the final phase of the transition, even before Chris Patten’s appointment, but his reform proposals might just have provided opportunities to score bigger propaganda and diplomatic points. The row over the Patten Proposals enabled Beijing to issue a warning that unilateral action would result in the setting-up of a “second stove” and, when it was formed, to say it was an unfortunate product of British confrontation.82

The term “second stove” was used in reference to various Chinese folk tales in which a second wife sets up a separate stove or kitchen to rival that of the first wife. The term denoted the seizing of initiative to control the establishment of the post-1997 political system. As Zhou Nan acknowledged, the Chinese side wanted to take an early initiative to make arrangements for the setting up of the HKSAR government83 although Beijing insisted that the Preliminary Working Committee was not a second power centre or a shadow administration. Chinese officials said it could not be so because it was an advisory body operating under the SCNPC in Beijing and not functioning in Hong Kong. Despite Beijing’s denial, the committee was generally seen to be a shadow government.84

The forming of such a body was not envisaged by either the Sino-British Joint Declaration or the Basic Law. When the legality of setting up such a committee was raised, Beijing argued that a decision made by the NPC on 4 April 1990,85 at the same time that the Basic Law was passed, provided that the NPC shall establish a Preparatory Committee for the HKSAR and that the Preliminary Working Committee was just preparation for the Preparatory Committee to be set up in 1996. It would “lay down the preparatory work for the future Preparatory Committee, including to the methods of forming the HKSAR government, legislature and other matters”.86

The Preliminary Working Committee held its first meeting in July 1993 and ended its work in December 1995. It consisted of 57 members, of which 30 were from Hong Kong. The large number of Hong Kong members was to make it palatable to Hong Kong people, but the composition of the Mainland members and the seniority of them was what really mattered. It was a body that enabled Beijing to coordinate its takeover of Hong Kong among the various parts of the Chinese political hierarchy. The chairman was Qian Qichen and the six vice-chairmen consisted of four Mainland officials (Lu Ping, Zhou Nan, Jiang Enzhu, and Zheng Yi). Mainland members included those with vice-ministerial rank from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, Ministry of Public Security, People’s Liberation Army, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, People’s Bank of China, and the CCP’s United Front Work Department. Of the Hong Kong vice-chairmen, were two tycoons who were among the most trusted by Beijing (Henry Fok and T. K. Ann) and a judge (Simon Li). Other Hong Kong members consisted of many of those who were the targets of the united front, such as David Li, Li Ka Shing, T. S. Lo, and Maria Tam. Old faithfuls, such as Tsang Yok Shing, were also included.

Although there were five sub-groups focussing on various aspects of local affairs,87 the main focus of work was to put forward proposals on political issues arising from the Reunification, in particular the formation of the first HKSAR government, the role of civil servants after 1997, and identifying existing laws that might contravene the Basic Law and to discuss what needed to be done. Beijing also expected the Preliminary Working Committee to work with other pro-Beijing organisations in Hong Kong, such as the Hong Kong delegates to the NPC and CPPCC, and the newly appointed affairs advisers, of which there were many overlapping memberships.88

Preparatory Committee

The Preparatory Committee was established on 26 January 1996. It consisted of 150 members with 94 Hong Kong appointees and 56 Mainland appointees. All the members of the Preliminary Working Committee were appointed to serve on the Preparatory Committee. The chairman was Qian Qichen. Lu Ping and Zhou Nan were two of the four vice-chairmen from the Mainland side. The five Hong Kong vice-chairmen were the familiar faces of Henry Fok, T. K. Ann, Tung Chee Hwa, Simon Li, and Leung Chun Ying. Mainland members included appointees from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, the Joint Liaison Group,89 the People’s Bank of China, the Bank of China, the State Planning Commission, the State Economic and Trade Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, the State Council Special Economic Zones Office and the Ministry of Finance. Representatives from security agencies included the People’s Liberation Army, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of State Security. There were also officials from united front organs like the CCP’s United Front Work Department, the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait and the State Council Overseas Chinese Affairs Office. Further, there were representatives from local authorities like the Shenzhen Communist Party Committee, the Guangdong People’s Congress and the Beijing Communist Party Committee. For the Hong Kong members, a large proportion of them were businessmen, and the rest were professional, pro-Beijing politicians, and representatives of other social sectors. Many of them were previously appointed as Hong Kong affairs advisers or delegates to the NPC and CPPCC.90

The Preparatory Committee was responsible for implementation work related to the establishment of the HKSAR, including the prescription of the method for the formation of the first government and the first Legislative Council of the HKSAR. It was also responsible for preparing the establishment of a 400-member Selection Committee, which in turn was responsible for the selection of the first chief executive of the HKSAR.91 Since the Preliminary Working Committee had in fact exceeded the parameters set for the Preparatory Committee in the Basic Law, the Preparatory Committee had a wider scope of work than the one set by the Basic Law. For example, it endorsed the Preliminary Working Committee’s proposal for a Provisional Legislature to be formed; gave advice on how the Mainland’s Nationality Law could be applied in Hong Kong; provided recommendations on how to interpret parts of the Basic Law; and recommended which existing laws contravened the Basic Law.

Selection Committee

The Selection Committee was created by the Preparatory Committee using a formula that represented the kind of selection method Beijing is most comfortable with. Under the Basic Law, the Selection Committee would have 400 members made up of Hong Kong permanent residents. The composition of this body required that membership be equally split among four broad functional sectors: industrial, commercial and financial; professional; labour, social services and religious; and politics (Hong Kong deputies to the NPC—those 26 members became members of the Selection Committee automatically, former political figures, and Hong Kong members of the National CPPCC). Three hundred members from the first three sectors were “elected” by all the members of the Preparatory Committee, and the number of candidates would be 20 percent more than the number of seats. Those from the first three sectors who wanted to be involved in the selection had to first submit his or her name to a body he or she was a member of (such as the Chinese Manufacturers’ Association or professional institutes). After the applications were reviewed by the relevant bodies, they could then be nominated to the Preparatory Committee. The list of nominations was then edited by the Secretariat of the Preparatory Committee after the closing date for entering names on 30 September 1996. The list was then given to all members of the Preparatory Committee to solicit opinions. After that, names could be put forward as candidates. On the method of the election, all members of the Preparatory Committee could vote for members of every sector of the Selection Committee. The ballots were anonymous. Those who won the most votes were elected. Those belonging to the fourth (politics) sector, who wanted to take part in the Selection Committee, could enter their names to the organisations of their own sector, or other sectors. They could be nominated to the Preparatory Committee after relevant organisations reviewed their applications. They could also be nominated by five preparatory committee members. There were a total of 5,789 applicants who put their names forward. On 2 November 1996, the 400 members were elected by members of the Preparatory Committee.

The Selection Committee was responsible for recommending the candidate for the first chief executive through local consultations or through nomination and election after consultations. The ambit of the Selection Committee was later expanded by the Preparatory Committee to include responsibility for the selection of the 60 members of the Provisional Legislative Council.

For the selection of the chief executive, three candidates received enough nominations (50 nominations from members of the Selection Committee) to stand for selection—Tung Chee Hwa got the largest number of nominations; Peter Woo, believed he had a chance and offered his own candidacy and scraped through; and T. L. Yang, a former chief justice, was supposedly the candidate encouraged by Xinhua Hong Kong to run. Simon Li failed to get enough nominations, and T. S. Lo had already pulled out of the race on 16 October 1996, when he realised he was not Beijing’s chosen one.92 A voting process was held and Tung was declared the winner.

Tung’s office and Executive Council

In setting up the Chief Executive’s Office, Tung Chee Hwa appointed Chen Jianping, known to be Lu Ping’s protégé and a former correspondent of Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po stationed in Beijing. A medium-level cadre, Chen’s role was to act as liaison between Tung Chee Hwa and the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office. Chen would continue to serve beyond Tung’s term to assist the other chief executives. Various mechanisms and channels were set up for Tung and his office to consult parts of the Central Authorities in Beijing ranging from hotlines between Tung’s office and Beijing, to regular reporting trips to the capital.93

Tung Chee Hwa was reputed to have consulted Beijing on many things major and minor. He wanted to ensure he knew what the bottom lines were so that he would not transgress them on a variety of issues. There were even rumours that he consulted Beijing so often that some cadres suggested to him that he could be more autonomous. Examples included whether to allow the Democratic Party and democrats to use the balcony of the Legislative Council Building in the early hours of 1 July 1997 to make their “we will be back” proclamation, as well as whether to allow all secretary-level civil servants to continue to serve in his administration. Reputedly Lu Ping made the decision to let the democrats go ahead and the CCP leadership decided all the serving secretaries should continue.94 Nevertheless, when the HKSAR government was planning to intervene in the market during the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998 and Tung asked Qian Qichen to send people to Hong Kong to discuss the government’s plans, Qian refused because it was a local matter.95

Tung Chee Hwa would go on to appoint his first Executive Council in July 1997. Unsurprisingly, his closest advisory body was dominated by members of the business elite and professionals with longstanding relations with Beijing. They included Leung Chun Ying, Henry Tang, who had inherited a textile business and was a member of the Liberal Party, Chung Shui Ming, a banker with the Bank of China and a member of the Hong Kong Progressive Alliance, Antony Leung, a banker, and Nellie Fong, an accountant. One DAB and FTU member were also appointed—Tam Yiu Chung, so as not to exclude a face that can claim to represent the grassroots. The most important aspect of Tung’s Executive Council was that it was considered entirely patriotic by the CCP.

Provisional Legislature

In August 1994, the SCNPC decided that the Legislative Council elected in 1995 would be disbanded at the time of reunification because the election methods used did not comply with Sino-British agreement. Shortly afterwards, a sub-group of the Preliminary Working Committee proposed that a provisional legislature should be set up instead as a temporary measure until such time as new electoral legislation could be passed that conformed with the Basic Law. The Chinese side claimed that forming a provisional legislature was a necessary response to the breakdown of the through-train arrangement caused by the British side. In March 1996, the Preparatory Committee, with one dissenter, voted in favour of the establishment of a Provisional Legislative Council with similar powers to those provided for the Legislative Council under the Basic Law.96 At about that time, Chinese officials had also let it be known in Hong Kong that any civil servant who wanted to participate in the post-1997 government must declare his or her support for the Provisional Legislative Council.97

The Provisional Legislative Council was created in December 1996 by block vote by the members of the Selection Committee. Among the 60 legislators so selected were 51 members of the Selection Committee (in other words, they voted to select themselves), 24 of whom were also members of the Preparatory Committee. Among them, 33 were legislators elected in 1995. Since the “pro-democracy” camp legislators stayed away because they regarded the Provisional Legislative Council as a body without proper legal foundation, those who filled the provisional body were essentially from the ‘pro-Beijing’ camp, which included 10 failed candidates in the 1995 election.98 The DAB had 10 seats, the Hong Kong Progressive Alliance also had 10 seats, and the FTU had one seat. This was the solid pro-Beijing core, and together they controlled 21 seats in the provisional body. The business-friendly Liberal Party had 10 seats and the Liberal Democratic Federation occupied 3 seats. From among the pro-democracy camp, only the Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood, a small political party, was willing to serve in the provisional legislature (they had 4 seats but would not have as many seats in the legislature again).

For the 33 legislators who served on both legislatures, they had to scurry between Hong Kong and Shenzhen since the Hong Kong Government refused to allow the Provisional Legislative Council to conduct meetings in Hong Kong alongside the Legislative Council. The provisional body operated in Shenzhen before the Handover with logistics support from the Shenzhen Municipal Government. In his capacity as the chief executive designate, Tung Chee Hwa proposed the Public Order (Amendment) Bill 1997 and the Societies (Amendment) Bill 1997. They sought to revive various provisions that the colonial administration had repealed to liberalise laws that restricted freedom of assembly and association.99 The provisional body passed the amendments even before the transfer of sovereignty, and with the passage of a special Reunification Ordinance enacted immediately after China resumed Hong Kong, these amendments were confirmed as laws of the HKSAR.

The Provisional Legislative Council moved to Hong Kong on 1 July 1997 and remained in office until the first HKSAR legislature assumed office in October 1998. During that year, it repealed or amended 25 pieces of legislation that were considered to have been in conflict with the Basic Law. The electoral laws based on the Patten Proposals were substantially changed, including the adoption of the proportional representation voting system using the Largest Remainder Formula. This was designed to enable the leftist camp to capture more seats in future legislative elections.100 Zhou Nan asserted that those provisions enacted during Patten’s time had the hidden intention of “undermining the governing capacity of the future HKSAR government”.101

A feature of the Provisional Legislative Council was that, when Tung Chee Hwa spoke there, legislators sometimes clapped their hands to show deference and support. With the new elected Legislative Council in 1998, this particular feature resembling Mainland political practice stopped, despite many of the provisional legislators being returned.102

NPC and CPPCC: Pre- and post-1997

The national NPC is comprised of delegates elected by lower-level people’s congresses in provinces and municipalities. Prior to 1997, the Hong Kong deputies to the NPC were chosen by Xinhua Hong Kong and endorsed by Beijing before being formally elected by the Guangdong Provincial People’s Congress to form part of the provincial delegation to the national legislature. Election in Hong Kong to the NPC was not considered possible under British rule. The sorts of people who used to be appointed to the NPC were leading left-wing figures from the labour, education, cultural and patriotic business sectors. However, from 1984 onwards, appointments begun to shift to the elites who were never part of the left-wing camp. There was a clear preference for appointing business elites. In 1988 and 1993 for the Seventh and Eighth NPCs, there were 18 and 26 Hong Kong appointees respectively. In 1988, there were 7 appointees from the business sector and 5 professionals. In 1993, there were 10 from the business sector and 8 professionals. In both NPCs, labour, culture and publishing combined only had 5 appointees.103

The selection of Hong Kong deputies to the Ninth NPC in 1997 after reunification initially provided much public interest because it gave Hong Kong a side seat to witness how the Mainland political culture worked. How would Mainland officials organise an election in Hong Kong? Some scholars believe the selection process became the most open in terms of Mainland experience in the history of NPC elections.104 A 424-member Electoral Conference was appointed by Beijing of which the 400-member Selection Committee made up the bulk of the electors. All in all, there were 22 NPC members, about 100 national CPPCC members, while another 50 or so were members of provincial people’s congresses or consultative conference members. While anyone who could get 10 nominations from the Electoral Conference could compete for the 35 seats, members of the Democratic Party did not manage to get past the door even though the party was given a chance to enter the race, as Tung Chee Hwa’s special adviser, Paul Yip Kwok Wah, publicly stated that if the Democratic Party wanted to enter the race he would be willing to be a nominator. This was an early olive branch from the CCP to the democrats, but it required them to be willing to enter the race and thereby signify their acceptance of the Mainland system. Their platform called for the end to one-party rule on the Mainland, which was a sign to the CCP that the Democratic Party remained in opposition and unpatriotic. Nominations became scarce for their three candidate and they eventually withdrew from the election altogether. Of the 35 deputies selected, the largest number of votes was won by Jiang Enzhu, the newly inaugurated director of Xinhua Hong Kong. His joining the race appeared nonsensical to the Hong Kong community since the people of the city did not ever consider Jiang able to represent them, but it provided Hong Kong with a quick lesson in Mainland politics. The NPC could not be equated with a parliament in the Western tradition. While it has formal law-making functions within the Chinese political structure, it is in effect “a concentrated manifestation of state power. Provincial interests were not so much represented there as ‘reflected’ in the formal presence of their delegations which were all headed by their provincial leaders.”105 In the HKSAR’s case, in the absence of Tung Chee Hwa heading the team of NPC deputies, Jiang Enzhu was there to enable the HKSAR deputies to stand on an equal footing alongside other delegations in accordance with the usual Mainland practice. Among the next highest vote getters were Ng Hong Man, Tsang Tak Sing, Maria Tam, and Rita Fan.106

For the election of the Tenth NPC in 2002, the number of seats was increased to 36 but tight control was exerted by the CCP Hong Kong. One of the candidates was Wang Rudeng of the Liaison Office, the successor body to Xinhua Hong Kong after 2000. This time, the Electoral Conference was made up of 953 appointed members including the expanded 800-member Election Committee that would also select the second chief executive plus numerous other pro-government figures. A total of 78 candidates fulfilled the requirement of getting ten nominations. Four members of the Democratic Party and Frederick Fung of the Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood sought to stand and got the required number of nominations. This caused some excitement in Hong Kong that Beijing might be prepared to accept a symbolic presence of the pro-democracy camp in the NPC. The Democratic Party candidates had toned down their platform and no longer called for the end to one-party rule. After the first round of voting to reduce the number of candidates to 54, the five democrats were eliminated. There were plenty of media stories that voters brought with them various lists of preferred candidates. For example, the DAB and FTU had preferred candidates. Insiders also claimed the Liaison Office had a recommended list. Topping the votes were Maria Tam, Wang Rudeng and Rita Fan. Some Liberal Party members did surprisingly well, and old timers like Tsang Tak Sing and Ng Hong Man only ranked relatively low but made the first cut. However, the second round of voting was what really mattered and it was this that showed the CCP’s order of preference. There was a considerable amount of behind-the-scene calculations and mobilisation to ensure certain people won and the most favoured ones got high votes. Thus, almost all the deputies to the Ninth NPC were returned. Rita Fan and Wang Rudeng were the top two vote getters. Members of the DAB, FTU and Hong Kong Progressive Alliance took a total of 12 seats.107

In 2008, members of the Democratic Party still did not make any headway to join the Eleventh NPC, but an unexpected candidate who just waltzed in was the former permanent secretary for education, Fanny Law, who resigned from government after an official inquiry found that she had interfered with academic freedom.108 This created an impression that the NPC seat was a consolation prize for a senior HKSAR government official whom the Mainland considered patriotic. In the past, favoured retired officials had been appointed to the CPPCC. In 2012, the Democratic Party did not bother to try to join the Twelfth NPC. Two minor members of the democratic camp made an attempt but they were never going to get anywhere.

While the NPC is an important body within the Mainland political system, the role of the Hong Kong deputies remains undefined. This problem arises because of how the deputies are chosen: essentially by an appointed election body. Moreover, there is also an attempt on the part of the Central Authorities to ensure the NPC deputies are not seen as a second power centre in Hong Kong. Thus, calls from the deputies for office and resource support have fallen on deaf ears. In March 2008, the SCNPC’s deputy secretary, Qiao Xiaoyang, told the Hong Kong deputies they did not need “to hang up a signboard” referring to the request for an office to be established in the HKSAR. Instead, the Liaison Office would request additional manpower and resources instead.109

As already discussed in Chapter 2, the CPPCC is China’s highest political consultative-advisory body and a national-level united front organ. It meets once a year in Beijing at the same time as the NPC sessions. The CPPCC is consulted on important political policies and major problems. Appointments of Hong Kong members in the run up to reunification formed part of China’s overall united front strategy to win hearts and minds, and it seems an understanding had been reached between the Liaison Office and the HKSAR government to involve CPPCC members more in local affairs through appointments to various bodies.110 In 1998, Hong Kong had two members among the 31 vice-chairmen of the Ninth CPPCC—Henry Fok and T. K. Ann. Henry Fok was the ultimate pro-China business tycoon—there was no one quite like him or who could match his patriotic credentials. His connections with China went back to the 1950s during the Korean War. He had never been part of the colonial establishment, never received any British honours and had always been low-key and low-profile. He had been a member of the CPPCC since the Fifth CPPCC in 1978 and vice-chairmen since the Eighth CPPCC. Fok had also been a member of the NPC since 1988. Indeed, he was the only person who served on the NPC, CPPCC and the Preparatory Committee concurrently, although already in his mid-70s by then, making him the most important and honoured person in the pro-China camp. T. K. Ann was a recruit from 1984 as a member of the Sixth CPPCC. His example is of particular interest for study. He was a successful textile industrialist in the 1950s and a member of the Legislative Council from 1970 to 1974. He was a member of the Executive Council under Governor Murray MacLehose from 1974 to 1979. He was awarded an OBE and later a CBE. In early 1982, Ann was invited by Xinhua Hong Kong to join the national CPPCC. During a trip to Tokyo together with Chung Sze Yuen and Kan Yuet Keung in February 1982, they discovered that all three had been so invited. Chung and Kan would decline the invitation but they provided the following analysis to their friend T. K. Ann:

[he] had already retired from the Legislative and Executive Councils, and later also from the chairmanship of the Trade Development Council. He was, however, still engaged in public affairs and was very knowledgeable about the operations of the Hong Kong Government. He could, and would, contribute his insights to the Chinese cause.111