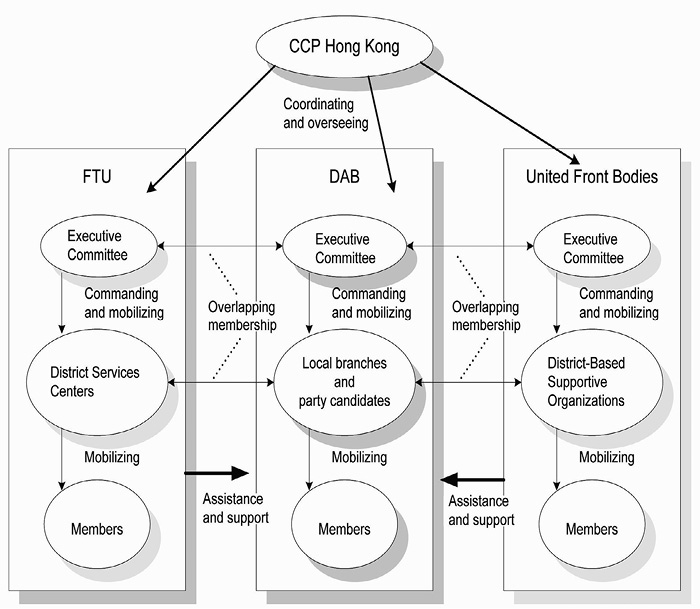

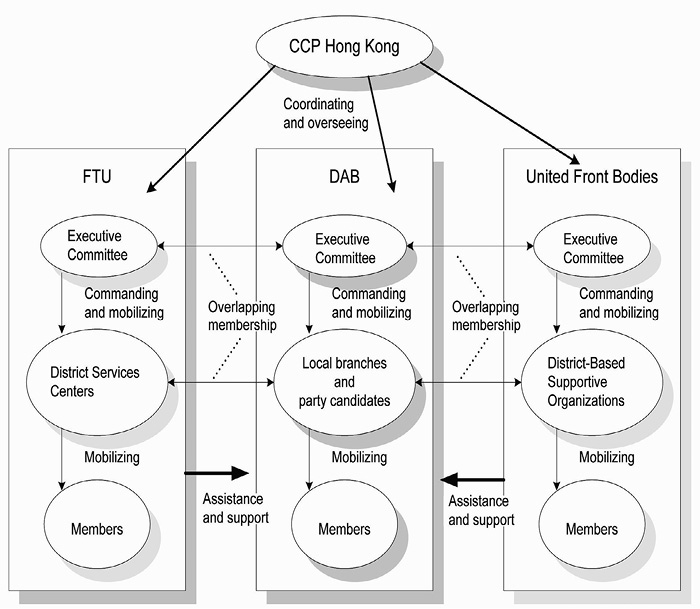

Figure 7 Triple alliance between DAB, FTU, and key united front bodies76

British rule ended in Hong Kong at the stroke of midnight on 30 June 1997. The return of this lost territory marked the beginning of a new era of Chinese Communist Party activities. The party built the new regime and fashioned a new political order to support “one country, two systems”. While the party could begin to look directly at things from inside Hong Kong, interpreting events and the mood of the Hong Kong community would prove challenging. The Mainland’s roots of suspicion of the former colonial entity, where people had lived under foreign influence for so long, ran deep. As such, the CCP’s disposition to distrust Hong Kong people, especially those whom they saw as having British or other Western connections, remained high. The underlying assumptions of how Mainland cadres saw Hong Kong and the world, and how Hong Kong people saw themselves and their worldview remained far apart. Hong Kong people also needed to get used to the fact that the HKSAR is no longer a faraway colony of a foreign power. After 1997, Hong Kong became a part of the People’s Republic and is important in national politics. Understandably, the CCP takes an intense interest in the HKSAR as part of a national political experiment.

The CCP could never quite forgive the British for changing Hong Kong’s depoliticised governing formula at the eleventh hour before their departure by insisting on elections. From its perspective, Hong Kong’s elections had to be managed to reduce the risk of surprise (i.e., unacceptable results). After 1997, extremely complex sub-sector elections select the chief executive, and similarly complex functional elections elect half of the legislators. These methods supposedly produce “balanced participation” in the political affairs of Hong Kong. In fact, they have entrenched many vested interests directly into the political system. The problem of legitimacy and fairness continues to plague the politics of Hong Kong.

The two post-reunification decades may be divided into three periods—with the eras of the three chief executives as the dividing lines. Between 1997 and 2003, the CCP took a hands-off approach with Tung Chee Hwa as chief executive. The CCP realised that it had a political crisis on hand after the seminal 1 July 2003 protest over the attempt to legislate national security laws required by Article 23 of the Basic Law. Its chosen leader for Hong Kong had effectively been deposed by a show of people power. The people were demanding a faster pace of democratic reform in the belief that it would underpin good governance. In 2005, the new era with Donald Tsang as chief executive started with high hopes for both the party and Hong Kong. Surprisingly, his administration lost popularity within a short time. By 2008, the CCP had already changed its approach to Hong Kong; and by 2009, the Hong Kong community got wind that there was a “second governing team” functioning alongside the HKSAR government. The era of Leung Chun Ying that started in 2012 was marked by several troubling mass movements. The younger generations promoted “localism” and ignited a surge of demand for autonomy, the most radical among them calling for “self-determination” and “independence”. This era was also marked by political disorder in the Legislative Council.

Twenty years after the reunification, the CCP has effectively “come out” in Hong Kong. Officials from the second governing team are visibly active. While the CCP could claim a measure of success in promoting its values and outlook in Hong Kong, the people there are girded by a different set of norms and they remain wary of being “mainlandised”. This is especially true of the younger generations, who have yet to reconcile with Chinese rule. The change in leadership in Beijing after the 18th National Party Congress in 2012 also had an impact on party leaders’ view on Hong Kong, as regime and national security became the most important objective in a politically volatile world. When Xi Jinping visited Hong Kong for the twentieth anniversary of the reunification, he emphasised that Beijing’s commitment to “one country, two systems” had never wavered. However, he asked Hong Kong people to be guided by a sense of “one country” but conceded that the “two systems” would not be neglected. He also drew a clear red line—Hong Kong must not use its privileged autonomy and freedoms to challenge state sovereignty, security, and development interests. Similar sentiments were expressed in Xi’s political report at the opening of the 19th National Party Congress in October 2017.

Mainland Institutions and Hong Kong

Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office

Soon after the reunification, Lu Ping retired as head of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office and was replaced by Central Committee member Liao Hui, the son of Liao Chengzhi, whose previous job was head of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office. Its prime responsibility after 1997 was to be the liaison and coordination channel between the HKSAR government and Mainland authorities and to act as the gatekeeper to prevent ministries and regional chiefs from interfering with Hong Kong. Liao’s policy was referred to as the “three nos”—“don’t criticise the HKSAR; don’t criticise the policies of the HKSAR; and don’t harp on about the bureaucratic links between the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office and the HKSAR”.1

The CCP’s policy over Hong Kong was reassessed and changed after the 1 July 2003 demonstration. Cao Erbao, head of the research department at CCP Hong Kong, wrote in 2008 in Study Times, a Central Party School publication, of there being two “governing teams” working to implement “one country, two systems”. The first was the local administration made up of the chief executive, political appointees, the civil service, and judicial personnel responsible to actualise the promise of “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong”. The second group was the Mainland team with responsibilities for Hong Kong affairs. This team was rather large and beyond the ambit of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office. These included “central government departments specialising in or are responsible for Hong Kong affairs; representative offices of the central government; other central government ministries responsible for national affairs and policies; and officials specialising in Hong Kong–related issues in the government and party provincial committees, autonomous regions and municipalities that are related to Hong Kong”. Cao described this second team as an “important governing force” and an “important outward expression of the ‘one country’ principle”. He stated that there were “matters that concern China’s sovereignty or come within the responsibilities of the Central Authorities or relationship between the Central Authorities and the HKSAR”. In other words, the second team supplements what the HKSAR government cannot deal with. Most notably, he argued that the Mainland team should operate legally and openly in Hong Kong, which would “reflect the significant historical change in the party’s role in Hong Kong”.2 His essay signalled that the CCP would be more explicit in its work in Hong Kong in the future. Cao’s description was not so different from Xu Jiatun’s idea of how the party might operate after 1997 (see “Introduction”). A commentary in a Macao newspaper noted that Cao’s essay spelled the “complete abandonment” of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office’s gatekeeping role and that under Hu Jintao’s leadership, the emphasis was on active engagement of the Mainland’s government and party functionaries in Hong Kong affairs rather than Jiang Zemin’s hands-off approach.3

Roles of the organs of state in Hong Kong

Post-reunification, there are three organs of state in the HKSAR.4 Apart from the party organ (Xinhua Hong Kong), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the People’s Liberation Army established themselves in Hong Kong after 1997. Though each is a separate body with no supervisory relationship, the party organ exercises de facto leadership over them. In July 1999, when President Hu Jintao visited Hong Kong to celebrate the second anniversary of the reunification, he spelt out their respective roles:

Xinhua Hong Kong has maintained a close relationship with Hong Kong, facilitated communication and cooperation between Hong Kong and the Mainland, and also effectively handled Taiwan-related matters and other matters assigned by the Central Government. The Commissioner’s Office of China’s Foreign Ministry assisted the HKSAR government in handling a large amount of foreign affairs matters, strengthened the connection and cooperation in economic and cultural areas between the HKSAR and foreign countries, regions, and international organisations. The Hong Kong Garrison of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has performed its duties in accordance with the law and established a good reputation. It has protected the national sovereignty and unity, territorial integrity, and the safety of Hong Kong.5

From Xinhua Hong Kong to Liaison Office

It was no secret that Lu Ping of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office and Zhou Nan, who headed Xinhua Hong Kong prior to 1997, had major disagreements over Hong Kong policy during the final years of the transition. Zhou was seen to be more intolerant than Lu, and the fact that the two institutions had overlapping functions made a turf battle inevitable, as it had been between Xu Jiatun and Ji Pengfei. As 1997 approached, the debate in Beijing was about the role of Xinhua Hong Kong post-reunification. Lu Ping and Tung Chee Hwa favoured a much smaller Xinhua presence; otherwise, it would be seen as the “hidden power” behind the HKSAR. After all, post-reunification, liaison and coordination between the Hong Kong and the Mainland authorities was supposed to be handled by the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office.6 The Central Authorities decided to scale down Xinhua gradually after 1997 by 60 percent.7

Zhou Nan retired in August 19978 and was succeeded by Jiang Enzhu, the Chinese representative in the Sino-British negotiations in 1993 and the Chinese ambassador to the United Kingdom from December 1995. Jiang said Xinhua Hong Kong was not another power centre and would not interfere in affairs that were within the autonomy of the HKSAR. He also indicated that the responsibilities of Xinhua Hong Kong had to be adjusted and that it would cooperate with, and support, the HKSAR government.9 However, scaling down Xinhua Hong Kong substantially did not happen. Instead, Jiang gave it a new lease of life through reframing its responsibilities.10 Moreover, Xinhua Hong Kong still needed to provide support to the DAB, FTU, Hong Kong Progressive Alliance, and other patriotic bodies.11

The status of Xinhua Hong Kong was raised. In January 2000, Xinhua Hong Kong changed its name to the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the HKSAR and relocated from Happy Valley to a new site in the Western District. The change was to reflect its official status as Beijing’s representative organisation in Hong Kong. The inclusion of the central government in the new name served to bolster its status. By the end of 2000, the number of staff had been trimmed down from 600 to about 400, much less than the 60 percent originally envisaged.12 After restructuring, there were 22 departments dealing with a wide range of activities, including research, culture, media and propaganda, education, youth, law, finance, security, Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, the New Territories, Taiwan, etc.13

In 2002, Gao Ziren, the deputy director, succeeded Jiang Enzhu as the next director. A key task for the Liaison Office was to help Tung Chee Hwa pass the Article 23 legislation so that Hong Kong would have laws to prohibit treason, secession, sedition, subversion, theft of state secrets, and ties with foreign political bodies. The Liaison Office’s responsibilities involved mobilising supporters, neutralising the majority, and defeating the “small” number of opponents. When the HKSAR government put forward the legislative proposal, Gao described it as “very lenient”.14 Tung Chee Hwa framed the passing of the proposed legislation thus: “it is the common responsibility of you and me as Chinese citizens to implement Article 23 of the Basic Law”.15 Maria Tam even said that anyone who did not support the Article 23 legislation was not fit to be Chinese.16 The left-wing press mounted a propaganda campaign to denounce opponents as traitors. Business tycoons, such as Li Ka Shing, Stanley Ho, and Gordon Wu felt they had to publicly support the bill.17 Various leftist groups organised seminars and wrote supporting submissions to the government. Twenty-seven pro-government organisations formed the Grand Coalition to Support the Enactment of Legislation to Protect National Security. The convener of coalition was the FTU’s Cheng Yiu Tong, who had been appointed to the Executive Council by Tung Chee Hwa. Senior local patriotic figures like Xu Simin, Tsang Hin Chi, and Chan Wing Kee joined a mass assembly where the coalition claimed more than 40,000 people from 1,500 organisations participated.18

From 2 April 2003, Hong Kong’s attention was momentarily diverted by the arrival of a new infectious disease—severe acute respiratory syndrome. However, once it had begun to subside, public attention turned back to the Article 23 legislation. Those opposing it called for more time for public consultation and amendment of certain provisions. The HKSAR government did not give way since its assessment was that it had enough votes in the Legislative Council to pass the bill on the scheduled date of 9 July 2003. The government’s insistence provoked a massive public demonstration on 1 July when more than 500,000 people took part in the protest. This was the seminal event that would change the CCP’s policy on Hong Kong. Many scholars have explored the events leading up to the demonstration. It suffices to say here that the civil society and pro-democracy groups that organised the march made sure the focus was on Tung Chee Hwa and his officials and not the CCP or the Chinese government to avoid direct confrontation with Beijing.19

Zou Zekai, the deputy director of the Liaison Office, used the Cultural Revolution as an example and said that street protests and demonstrations would eventually lead to the complete collapse of Hong Kong’s economy.20 The Liaison Office apparently thought the demonstrators were paid to protest. It had reported internally that each demonstrator was paid HK$300 to march, while those who shouted slogans were paid HK$500 each. And to make the foreign connection clear, it had reported that the money was channelled through the American investment bank, Morgan Stanley.21 If such a report had indeed been made, it would have been blatantly untrue but it could have perpetuated the longstanding belief within the CCP that foreign forces were trying to destabilise Hong Kong.

Within days of 1 July, the Politburo convened an enlarged meeting and decided that Hong Kong should keep to the original schedule to pass the bill.22 Gao Siren echoed that there should be no delay; and Mainland enterprises issued an open letter opposing postponement.23 However, with the Liberal Party supporting a delay, Tung Chee Hwa had no choice but to abort passage of the bill as the HKSAR government would not have sufficient votes to push it through.24 Gao then changed his tone and said he respected Tung’s decision.25 He added that the Tung administration should reprioritise efforts to address economic issues instead.26

The 1 July demonstration was a serious setback for the Liaison Office. It had seriously underestimated feelings in Hong Kong and the number of protesters joining the march. People were unhappy not just because of the Article 23 legislation but the community had been through several years of a weak economy and deflation, and the public mood had turned negative. Beijing must have received conflicting information just prior to the protest ranging from a relatively low turnout to figures well over 200,000. Premier Wen Jiabao, who was in Hong Kong between 29 June and 1 July, left for Shenzhen after the official reunification anniversary celebrations that morning and watched what happened in the afternoon from Shenzhen. Wen was apparently enraged by the Liaison Office for not getting matters right.27 Even the veteran leftist Xu Simin criticised the Liaison Office for not having done enough united front work in Hong Kong. Moreover, Xu said that after the 1 July 2003, the Liaison Office “just disappeared after things went wrong”.28

Personnel and structural changes were made at the Liaison Office. In 2009, Gao Siren was succeeded by his deputy, Peng Qinghua, an experienced cadre who had once served in the CCP’s Organisation Department. He had already been made a member of the Central Committee of the CCP in 2007. In 2012, Zhang Xiaoming, deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, succeeded Peng. In the same year, he was made an alternate member of the Central Committee of the CCP, which is one rank lower than all previous directors of CCP Hong Kong—and one rank below Wang Guangya, the director of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, who was his former boss. This signalled that decisions were made in Beijing and the Liaison Office was expected to implement them. Zhang was made the head of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office soon after the twentieth anniversary of the reunification and was also elevated to full membership of the Central Committee of the CCP at the 19th National Party Congress. His successor at the Liaison Office is Wang Zhimin, former head of the Liaison Office in Macao, who was also made a full member of the Central Committee. Wang used to be a deputy director at the Hong Kong Liaison Office (2005–2009) in charge of youth affairs. Their promotion to the Central Committee signalled the importance the party places on Hong Kong matters.

The Liaison Office’s responsibilities are:

1. Liaising with the Commissioner’s Office of China’s Foreign Ministry in the HKSAR and the Hong Kong Garrison;

2. Liaising and assisting relevant Mainland authorities to manage the Chinese enterprises in Hong Kong;

3. Facilitating cooperation between Hong Kong and the Mainland on the economic, education, scientific, cultural and sports areas etc.

4. Connecting with local people from various sectors, facilitating communication between Hong Kong and the Mainland, and reflecting Hong Kong people’s views on Mainland affairs;

5. Handling matters related to Taiwan; and

6. Handling other duties assigned by the Central People’s Government.29

It is unclear how many people work at the Liaison Office today. The Office had bought many residential properties worth hundreds of millions of dollars,30 presumably for staff and visitors, indicating that increasing numbers of Mainland cadres and officials go to Hong Kong for work and visits. Rita Fan revealed in 2017 that all the staff at the Liaison Office were from the Mainland—mostly from Guangdong with the rest from Fujian and other places. She suggested that the Liaison Office should hire Hong Kong staff so that it could understand local culture better.31 Her statement was a sign that even among those who were closest to the CCP in Hong Kong, there were still sentiments that Mainland officials in Hong Kong did not understand how the local people think and thus were unable to reflect matters fully or accurately to Beijing.

Commissioner and commander

The Office of the Commissioner of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has a major presence in the HKSAR.32 The first commissioner was Ma Yuzhen, a diplomat, who was ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1991 to 1995, and vice-minister at the State Council Information Office prior to going to the HKSAR. Generally, the Commissioner’s Office operated in a low-profile manner. Nevertheless, occasional comments about local affairs were made. For example, Ma warned that Hong Kong should not be used as an “operation base” by the Falun Gong, which Beijing had declared an “evil cult”.33 In 2000, when Chris Patten (then a European Union commissioner) remarked on various local issues when visiting Hong Kong, the Commissioner’s Office issued a statement criticising Patten for commenting on China’s internal matters.34 Likewise, it criticised the United States government for interfering in Chinese affairs after the Department of State released its China Country Report on Human Rights Practices, which included sections on Hong Kong and Macao.35 The Commissioner’s Office also responded to foreign news articles to emphasise the Chinese government’s “zero tolerance” for “Hong Kong independence in whatever form”.36

The stationing of the Hong Kong Garrison in the HKSAR is provided for in Article 14 of the Basic Law, as well as the Mainland’s Law on the Garrison of the HKSAR. Advance Garrison personnel arrived in Hong Kong between April and May 1997 to prepare for the transfer of defence responsibility from the British, and 500 advance troops entered Hong Kong on 30 June 1997. A 4,000 contingent of ground, navy, and air personnel arrived on 1 July 1997. Its headquarters is at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Forces Hong Kong Building (previously known as the Prince of Wales Building) at Tamar and it also controls former British army sites. The Garrison is led by both a military commander and a political commissar. The cost of keeping the Garrison in Hong Kong is borne by the Central People’s Government. Its main responsibilities are to prepare against and resist aggression, safeguard the security of the HKSAR, carry out defence duties, control military facilities, and handle foreign-related military affairs. Upon the request of the HKSAR government, the Garrison may provide assistance in the maintenance of public order and disaster relief.37 In 2012, there were 15 squads in the Garrison, which had increased to 20 squads by 2017. The Garrison is part of a larger national army and has become a well-equipped combat-ready force. While it is under the direct leadership of the Central Military Commission, administrative control rests with the Southern Theatre Command (former known as the Guangzhou Military Region).38 The Garrison can also play a role in international affairs. For example, in November 2016, its officers took part in the first ever joint military exercise overseas with their Malaysian counterparts,39 and on 5 June 2017, it conducted an air and naval patrol off Hong Kong waters, likely to show China’s determination to protect what China regards to be Chinese waters in the South China Sea.40

The Garrison had initial difficulties adapting to Hong Kong. In 2002, Commander Xiong Ziren said that Hong Kong had “a variety of political groups, social organisations and factions. They have different political views and inclinations. Hostile forces inside and outside the country always tried to take every opportunity to corrupt, befriend and instigate the Garrison”, Xiong then provided a standard Mainland description of Hong Kong—that Hong Kong had been separated from the Mainland for a long time, people had a colonial education, and there were “anti-China and extreme rightist forces” both within the territory and on the outside. These characteristics resulted in Hong Kong people holding biases and misunderstanding about the CCP and Chinese government.41 It could equally be said that in perpetuating this line of thinking, the party sustained biases and misunderstandings about Hong Kong and its people.

The garrison had to flex its muscles from time to time to send signals to Hong Kong people. It held the biggest military parade outside Beijing on 1 August 2004 to mark China’s Armed Forces Day with 3,000 troops and armoured vehicles. On that occasion, Commander Wang Jitang stated his support for the then beleaguered Tung Chee Hwa.42 On 24 January 2014, the Garrison staged a first air-and-sea drill across Victoria Harbour, providing a warning sign after several activists had broken into the Tamar headquarters on 26 December 2013, waving a colonial-era flag and calling on the PLA to “get out”.43 On 1 July 2014, the garrison opened its doors to the public at three bases, as demonstrators gathered to stage their annual march for democracy.44 The garrison held a live-fire exercise at the Castle Peak Range on 4 July 2015.45 A major land-sea-air drill was staged on 31 October 2016, soon after two winners of the 2016 Legislative Council election used their oath swearing to promote independence.46

Over time, the garrison was also assigned united front work. An early example was in May 2005, when legislators from the democratic camp were invited to visit the military camp on the garrison’s Open Day. The invitation was widely seen as an attempt by Beijing at reconciliation with the democrats after Tung Chee Hwa stepped down.47 The garrison’s overall united front work had been extensive. Since 1997, it had allowed over 620,000 people to visit army sites, trained young people at military summer camps, planted tens of thousands of trees, donated blood, and assisted thousands of seniors and children in care homes. Its military marching band and artistic team also performed for local residents on many occasions.48 It was no small feat that the garrison developed a reasonable image in Hong Kong as could be seen from public opinion surveys in 2004 and 2015.49

Political Disorder and Governance

A constant feature of post-reunification Hong Kong between 1997 and 2017 was disorder. While the CCP fashioned a new regime filled mainly by “patriots”, the post-1997 government faced many difficulties and Hong Kong people remained generally dissatisfied. The legitimacy and authority of the chief executives and their governing teams came under repeated challenge. The Hong Kong community saw the electoral system as manifestly unfair. There was a chance in 2015 to take a step forward but it was lost due to miscalculations by the democrats. Civil servants were also thought to be insufficiently supportive of the chief executives.

Dealing with elections

“Elections” was one of the very last points agreed between Britain and China and the British knew that the Chinese never bought into Western-style free elections. The bicultural nature of the Sino-British Joint Declaration meant that the word “elections” reflected the values, meanings, and understandings of two very different political systems (Chapter 8). The Basic Law, finalised after the trauma of 4 June 1989, spelt out the post-1997 framework on elections. The CCP’s concern has always been that political power in Hong Kong must rest with “patriots” (Chapter 9). The compromises in the Basic Law did not mean the inherent contradiction in how “elections” is understood had been resolved—only that they would come to the fore after 1997.

The Basic Law provides that the “ultimate aim” is the election of the chief executive and all legislators by universal suffrage with the proviso that the pace of change would depend on “the actual situation” and that “the principle of gradual and orderly progress” had to be taken into account. The Basic Law provides that the methods for elections could change after 2007 but the drafters ensured that the bar is set high—it would need the support of a two-thirds majority in the Legislative Council, the chief executive’s consent, and the “approval” of the SCNPC in the case of change of electoral method for the chief executive, and “reporting for the record” in the electoral method of the legislature.

For Hong Kong, Beijing promised universal suffrage but the goal posts kept being moved. Democrats wanted universal suffrage to be achieved in 2007 for the chief executive election and in 2008 for the whole legislature. For Beijing, it was too soon. Another opportunity arose for the chief executive election in 2017 to be by universal suffrage. When discussion started in 2013, the Central Authorities were willing to allow Hong Kong voters to directly elect the chief executive, but there would need to be a nomination process to screen out candidates unacceptable to Beijing. For the CCP, this was a major concession. A screening device was essential because who becomes chief executive is a matter of national security. The pro-democracy camp wanted a nomination process without filter. The eventual proposal was voted down in 2015 to the disappointment of many people. Almost immediately, the pro-democracy camp asked for talks on electoral reform to start again. It may be assumed that if the timing and details of reform could not be agreed between Beijing and Hong Kong, Beijing would simply not allow election by universal suffrage to take place.50 It is inconceivable to the CCP that the position of chief executive is not filled by a trusted person. From time to time, Chinese officials repeat Deng Xiaoping’s explanation from the mid-1980s—the post-1997 political model would be an “executive-led system” and not a Western model with “separation of powers”.51 What it means is that the Central People’s Government governs the HKSAR via the chief executive.

The election of the Legislative Council is a balancing exercise between direct election on a geographical basis and election through functional constituencies. The CCP’s approach is to ensure that patriots win a majority of the seats. The assumption was that the patriotic majority would ensure smooth conduct of government business through the legislature. That assumption proved to be wrong.

Patriots, elections, and opposition voters

Between 1984 and 2004, the CCP used various occasions to describe what it took to pass the patriotism test. It included loving China and Hong Kong, respecting the Chinese nation, supporting the resumption of sovereignty over Hong Kong, not impairing Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability, not subverting the authority of the Central Authorities, not supporting Taiwan and Tibet independence, not colluding with foreign powers to interfere with China’s internal affairs, and not endangering state security by opposing the Article 23 legislation.52 In 2013, in discussing the nomination process for selecting chief executive candidates for the 2017 election, Qiao Xiaoyang, chairman of the NPCs Law Committee, said that no person who “confronts” Beijing could lead the HKSAR;53 and Zhang Xiaoming said politically undesirable candidates should be excluded.54 In June 2014, the State Council made it absolutely clear why being patriotic is important:

Hong Kong must be governed by Hong Kong people with patriots in the mainstay, as loyalty to one’s country is the minimum political ethic for political figures . . . [otherwise] the practice of “one country, two systems” in the HKSAR will deviate from its right direction, making it difficult to uphold the country’s sovereignty, security and development interests, and putting Hong Kong’s stability and prosperity and the wellbeing of its people in serious jeopardy.55

To the CCP, democracy is not the end goal but a means to choose safe hands—“patriots”—to run Hong Kong. The electoral systems for the chief executive and half the legislators have a congenital design flaw, however. They are dominated by various vested interests for which Hong Kong pays a heavy price in efficiency, innovation, and competitiveness. Moreover, the public see the electoral systems as grossly unfair, as vested interests take precedence over the public interest; and here lies a crucial part of the people’s discontent.

Among Hong Kong voters, there is a hardcore group that supports the opposition. The 2010 by-election showed the size of this group, as well as the strategising capability of the CCP. The League of Social Democrats floated the idea in July 2009 that the democrats should provoke a by-election and use it as a de facto referendum of public desire for universal suffrage to be achieved at the 2012 elections for both the chief executive and the legislature. The League of Social Democrats and the Civic Party joined hands in this enterprise. Five legislators from the two parties resigned in January 2010 to trigger the by-election, which was held on 16 May 2010. The CCP’s counter-strategy was not to field candidates thereby minimising voter turnout so that the by-election could not be considered a referendum. Beijing adopted this strategy because it was unsure whether the pro-government side would do well enough to make a direct punch-up worthwhile. Moreover, a full-scale battle ran the risk of allowing the democrats to claim the by-election was effectively a referendum. Tactically, the pro-government camp questioned whether the by-election violated the Basic Law and attacked the perpetrators for destabilising Hong Kong and wasting time and resources. With no credible opponents, the one-sided by-election returned the five legislators who resigned. The turnout rate was 17.19 percent representing 579,795 voters, the bulk of whom may be said to be hardcore opposition voters.56

Election of the chief executive

Members of the chief executive Election Committee are made up of ex officio members from political bodies and representatives from business, community, and the professions. Except for the ex officio members, Election Committee members are chosen from various sub-sectors, which are both corporate and personal in nature. Corporate sub-sectors include such bodies as chambers of commerce, employers’ federation, manufacturers’ association, enterprises association, banks, and associations made up of property-related companies and even transport-related bodies. The nature of corporate voting is that those who control a member corporation effectively control its vote. Those sub-sectors that are personal in nature are tied to specified professions. For example, the accountancy sub-sector is made up of certified public accountants. Likewise, the legal, engineering, medical, and education sub-sectors are made up of members of those professions. The idea for functional elections was the creation of the pre-1997 colonial administration, designed to co-opt the then pro-establishment business and professional elites when election to the Legislative Council was first introduced in the 1980s.

Over the course of the post-1997 years, more political bodies and sub-sectors were added to expand the size of registered electors and members of the Election Committee. By the 2017 chief executive election, there were 38 sub-sectors, and the number of registered electors grew from under 132,000 to over 230,000. The size of the Election Committee expanded from 800 members in 2002 to 1,200 members in 2012. The HKSAR government worked out all the eligibility details. In the eyes of the CCP, the election of the chief executive became increasingly democratic because “such a composition is an expression of equal participation and broad representativeness”.57 Along this line of thinking, having the overwhelming support from the Election Committee is the proxy for having the support of Hong Kong society. Thus, the driving force for the CCP in chief executive elections is to ensure its candidate has the overwhelming support of the Election Committee.

In the case of Tung Chee Hwa’s re-election in 2002, while it was unchallenged, the party had to show that Tung had strong support. While a candidate only needed 100 nominations, Tung got over 700 nominations. Party officials made it clear that to maintain “stability and continuity” it was best that Tung served a second term.5858 Hong Kong NPC and CPPCC members, business tycoons, and leftist leaders were mobilised to show support, some of whom felt pressured, fearing that non-cooperation would be reported to the Liaison Office.59 In gratitude, Tung later described the Liaison Office as the “HKSAR government’s best friend”.60 After Tung stepped down in 2005, an election had to be organised. Beijing decided that Donald Tsang, the then chief secretary, should be the successor. Tsang was the only valid candidate and got 674 nominations.

Donald Tsang’s re-election in 2007 was more challenging. The pro-democracy camp participated in sub-sector elections to win seats to the Election Committee by relying on sub-sectors for the professions. The democrats fielded Alan Leong of the Civic Party. Donald Tsang secured 641 nominations. Alan Leong got 132—enough to get to the starting line. Even though Tsang would win, the CCP knew some Election Committee members had reservations. The party wanted to minimise blank votes since it would show internal division. A good occasion to wheel out “big guns” to lobby for Tsang was in March 2007 in Beijing, when many of the Election Committee members were there for the annual meetings of the NPC and CPPCC. The head of the United Front Department, Liu Yandong, hosted meetings to consolidate votes.61 In the end, Donald Tsang got 649 votes and Alan Leong got 123 votes. There were 11 blank votes and six Election Committee members did not vote. The most memorable aspect of the 2007 election was two widely watched televised debates, where the sure winner had to justify his policies and governance style—a welcomed experience for Hong Kong.

The 2012 chief executive election was more gripping. The punch-up was between two high-profile patriots—Henry Tang, a second-generation tycoon, who was Donald Tsang’s chief secretary—and Leung Chun Ying, who had been the secretary of the Basic Law Consultative Committee in the 1980s and served on the Executive Council under Tung Chee Hwa and Donald Tsang. In July 2011, Wang Guangya articulated Beijing’s criteria for the next chief executive: the person should be patriotic and love Hong Kong, be able to govern, and be broadly acceptable to the people.62 Unlike before, Beijing did not express a preference. As the size of the Election Committee had been increased to 1,200 members, candidates had to obtain 150 nominations to get to the starting line. Henry Tang got 390 nominations and Leung Chun Ying got 305. The democrats fought for seats to the Election Committee, like they did in 2007, and fielded legislator Albert Ho of the Democratic Party. Ho garnered 188 nominations but was a side show. There was no clear indication of preference from Beijing even by the annual meetings of the NPC and CPPCC. There was much speculation about why Beijing did not indicate a preference, and why Wang added public acceptability as a criterion. One line of thinking was that leaders had different preferences, or that either was acceptable. Another line of thinking was that the public acceptability criterion was put forward because Leung Chun Ying’s supporters in Beijing thought he was the more popular candidate and it was an indirect way of showing support early in the race without articulating a preference. Tang and Leung fought a bruising battle. The media revealed Tang’s marital infidelities and that he had an unauthorised underground extension in his home. Tang claimed at a televised debate that Leung had suggested at a confidential meeting to use the riot police and tear gas against protesters in 2003, which Leung denied. Tang’s claim could not be substantiated and he breached the confidentiality of high-level government meetings. The CCP threw its weight behind Leung after that debate. Leung reaped 689 votes, Henry Tang got 286 votes, and Albert Ho received 76 votes.

The 2017 chief executive election had many surprises. Veteran DAB member Tsang Yok Sing sought but failed to get Beijing’s support to run.63 Long-time patriot, Regina Ip, failed to get to the starting line but Woo Kwok Hing, a retired judge, did.64 Leung Chun Ying did not seek re-election.65 John Tsang, the financial secretary, said a reason he sought the top job was that he had an unexpected handshake with Xi Jinping in 2015.66 The democrats managed to grab 325 Election Committee seats and decided to back Tsang.67 A Wen Wei Po commentary described Tsang as the proxy of the opposition.68 Lo Man Tuen, the vice-chairman of the CPPCCs foreign affairs sub-committee, added two further reasons why Tsang was unacceptable to Beijing: he “lacked principle on major issues”—referring to his non-committal attitude to mass protests and he ignored signals from Beijing urging him not to run.69 Carrie Lam, the chief secretary, who was preparing for retirement, became Beijing’s candidate. She received 579 nominations. Woo Kwok Hing and John Tsang garnered 179 and 160 nominations respectively. The televised debate on 14 March 2017 did not have the high drama of 2012. The most notable aspect of the other televised debate organised by the Election Committee on 19 March 2017 was how few Election Committee members bothered to show up. Only 507 members attended. With more than 200 from the opposition camp targeting Lam, she had a tough ride.70 In the end, she got 777 votes. John Tsang received 365 votes and Woo Kwok Hing got 21 votes.

Bernard Chan, executive councillor and the campaign director for Carrie Lam, noted what it was like to run in Hong Kong’s chief executive election. It provides a window into how the vested interests lobby for their causes:

We needed to win over a majority – and preferably a sizable one – of the . . . Election Committee . . . In theory, it should not be too difficult to lobby for votes . . . In practice, it is impossible to address the committee as a single group. It is a small body, so every individual vote counts. Yet the body is splintered into 38 subsectors, many of which are fairly narrow constituencies. Every candidate must visit all of them, listen to their concerns and give them reasons why they should back him or her. This electorate is not simply split into two or three broad factions. Many of these groups have very specific positions on issues to do with their industries or professions. Quite a few have very detailed demands. In some cases, the demands are impossible to meet. And some are contradictory.71

Strategising and mobilising for elections

The CCP has been successful in mobilising the united front forces at elections and strategising for the best outcomes through optimising the placement of candidates in constituencies. Its success has been built upon investing time and resources to turn the DAB into the dominant party, assisting other pro-government parties, and maintaining alliances among patriotic bodies to turn out the vote. In other words, Xinhua Hong Kong and its successor body, the Liaison Office, is the mastermind behind elections for the pro-government camp.

The DAB was established in 1992 with 56 members. Even by the 1999 District Councils election, it was already the best organised political party in Hong Kong. By 2005, it had absorbed the moribund Hong Kong Progressive Alliance. By 2017, the DAB had over 32,000 members, including 117 district councillors, 12 legislators, as well as 7 NPC and 25 CPPCC deputies.72 Just how close the DAB is to the Liaison Office could be seen from its biannual fundraising event. In 2014, the event raised nearly HK$70 million. Zhang Xiaoming donated a piece of his own calligraphy that sold for HK$13.8 million. In 2016, the DAB raised HK$60 million that included another piece of Zhang’s calligraphy that fetched HK$18.8 million. Pro-Beijing business people were extremely generous in opening their wallets.73

Overlapping memberships among the DAB, FTU, and key united front bodies result in a “triple alliance” among them to count on each other for campaigning support.74 The Liaison Office also supported “independent” candidates to win seats at district and legislative elections. For example, in the 2015 District Council elections, out of 943 candidates, 384 of them declared themselves to be independent or non-affiliated candidates but 88 of them were found to be active members of pro-government political groups.75

Figure 7 Triple alliance between DAB, FTU, and key united front bodies76

In 1999, a part of the electoral landscape was changed to disadvantage the opposition. The elected Urban Council and Regional Council were dissolved. These bodies had executive power and budgets to run sanitation services, fresh food markets, and sports and cultural events. Doing away with them not only centralised power within the HKSAR government but also removed the electoral bases of many opposition councillors. At the same time, the advisory District Boards (Chapter 7) were transformed into the District Councils. Tung Chee Hwa brought back a number of appointed seats to the District Councils between 1999 and 2015 (appointed seats were eliminated before 1997), which was another way to dilute the influence of the opposition. There are 18 District Councils with 458 elected seats for the 2016–2019 term of office. District Councils election are on a first-past-the-post basis.

When sacrifices had to be made, it was clear who had priority. In the 2008 Legislative Council election, the Liaison Office’s last minute “get out the vote” effort went to the DAB–Heung Yee Kuk alliance over the Liberal Party.77 Extra effort also went to the DAB instead of the FTU in the 2016 election, which veteran unionist Wong Kwok Hing believed led to his defeat.78 Favouritism at election no doubt hurt the feelings of those who felt they did not get sufficient help.

Ideologically, the FTU represents grassroots and blue-collar workers’ interests while the DAB represents lower-middle and middle-income interests. The Liberal Party is pro-business and aligns with upper economic circles. Internal strive caused the Liberal Party to split after the 2008 election. Over time, through reorganisation and rebranding among pro-business patriotic politicians, the Business and Professional Alliance for Hong Kong was formally created as a political party in 2012. The New People’s Party, founded by Regina Ip in January 2011, is also part of the pro-government camp. Michael Tien left the New People’s Party in 2017 to form the Roundtable Pragmatism.

Pro-Government Forces in 2016–2020 Legislative Council and Year of Formation

1948: Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (FTU)

1992: Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong (DAB)

1993: Liberal Party

1999: New Century Forum

2011: New People’s Party

2012: Business and Professional Alliance for Hong Kong

2017: Roundtable Pragmatism

Fragmentation and veto power

The Legislative Council is made up of geographical and functional members in equal proportion. To ensure the DAB could win more seats in the geographical constituencies, the pre-1997 first-past-the-post election system was replaced by proportional representation using the Largest Remainder Formula from the 1998 election. This kind of system favours weaker parties, which was what the DAB needed at the time. Functional elections are like sub-sector elections described above for the chief executive election.79 A mark of functional constituencies is the high frequency of there being just one candidate who is automatically elected in the business-related seats. In other words, these are seats that are spoken for, where the vested interests agree who should represent them, such as in real estate.80 While functional seats are mainly held by pro-government lawmakers, the opposition has been able to hold on to various constituencies with individual voting, such as for teachers and lawyers.

The combination of the proportional representation method for geographical election and functional elections has enabled the patriotic forces to win a majority of the legislative seats from election to election but the same system is also limiting the advance of both the pro-government and pro-democracy forces. What cannot grow tends to fragment.81 Proportional representation enables even small groups to have a chance to win. On the pro-democracy side, small parties have grabbed seats, such as the League of Social Democrats and People Power. In the 2016 election, new opposition groups—Demosistō, Democracy Groundwork, Land Justice League, and Civic Passion—each won a seat, and Youngspiration won two seats. They have also split the pro-democracy camp between the traditional democrats and a radical faction. A further observation can be made: despite the fierce battle for seats, the overall result between the pro-government and pro-democracy camps is about winning or losing at the margins that affect a very small number of seats.

The opposition’s ability to retain one-third of the seats enabled the democrats to veto government proposals to change the electoral system, as the Basic Law requires a two-thirds majority in such cases. On 18 June 2015, the Legislative Council voted down the HKSAR government’s electoral proposal for the chief executive to be elected by universal suffrage in 2017. It was expected that the package would not pass as there was insufficient support for the two-thirds majority needed. What will not be forgotten in Hong Kong’s legislative history is the bungling of the vote by the pro-government camp. Only eight pro-government legislators voted for the proposal, as the others walked out in the mistaken belief that the vote would be adjourned while they waited for Lau Wong Fat of the Heung Yee Kuk to arrive. Confusion was caused by the spur-of-the-moment request from Jeffrey Lam of the Business and Professional Alliance to the president of the Legislative Council to adjourn the vote, which prompted the DAB’s Ip Kwok Him to signal to pro-government lawmakers to leave the chamber. In fact, the voting process had already been initiated.82 Not only was the pro-government camp unable to blame the opposition for rejecting reform, they were widely ridiculed for getting things so wrong. There were tears and apologies.83 Beijing was surprised by the walkout. A Mainland official admitted what happened was “embarrassing”.84

Filibuster and disorder

The bungling of the crucial vote on 18 June 2015 illustrated a recurrent problem with the pro-government camp. Like the pro-democracy camp, it is also fragmented and pluralised. While it is common for parliamentarians to time their presence in the chamber to when they expect to speak or cast their vote, opposition lawmakers in Hong Kong had exploited the lack of resolve of pro-government lawmakers to stay in their seats by using the filibuster to delay or stop legislative proceedings. The pro-government lawmakers could have minimised the filibuster by being present during legislative meetings to discourage time-wasting quorum, division, and adjournment calls. The efforts of just a handful of the more radical lawmakers to sustain tedious filibustering proved most effective. Through perfecting the art of filibustering during the Leung Chun Ying administration, the opposition substantially affected government business.85 From the HKSAR government’s perspective, the cost to effective governance was enormous:

This is already the fourth year in which Members put forward loads of amendments to the Appropriation Bills and made incessant quorum calls . . . driving the Government to the verge of a “fiscal cliff” . . . [Other] meetings . . . have also been affected by individual Members’ filibusters from time to time. The objective result is a serious congestion of agenda items.86

The financial secretary made a point of noting on 26 April 2017 in relation to the 2017–2018 Budget that:

In the past four fiscal years . . . on average, over 16 meeting days are required each year for the passage [of the Budget] . . . which is six times the average time needed for scrutinising the same bill . . . since 1997.87

The pro-government camp is in fact just a mixed bag and motley crew with different interests. Its deficiencies were colourfully described by the head of the Central Policy Unit, Shiu Sin Por, in March 2016. He criticised its lawmakers for “messing around” with their own agendas and failed to fulfil their duties, while still collecting a decent pay cheque every month. He highlighted their poor communication, inability to work together, and unwillingness to sit through meetings to prevent filibustering.88 Tung Chee Hwa suggested in June 2016 that the HKSAR government might work more closely with the pro-government camp to solve the problem of lack of unity. He lamented that all three chief executives could not run an “executive-led” government:

As a result, past administrations have been unable to achieve what they aspired to. The problem is that . . . the chief executive does not lead any political parties, while the lawmakers are popularly elected. Of the lawmakers, some are non-affiliated while even more are attached to different political parties. They represent different interest groups, and have thus constantly disputed with one another and the SAR government. Therefore, the chief executives found it difficult to effectively execute the executive-led governance model as stipulated under the Basic Law, resulting in even greater friction . . . The government should work even closer with the pro-establishment camp, build a closer partnership relationship with them, and allow them to get more involved in the implementation and discussion of government policies. At the same time, the pro-establishment camp not only should consider the interests of their voters, but also should think about the interests of the whole of Hong Kong.89

Chief executive and civil service

The CCP’s assumption was that with Tung Chee Hwa as chief executive, supported essentially by the senior ranks of pre-1997 civil servants, the administration of the HKSAR would function effectively from day to day. Yet, this did not happen. There were two sets of circumstances which casted doubts about the competence of the first post-1997 government. Firstly, the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and its aftermath drained confidence, as stock and property markets collapsed. The HKSAR government took aggressive and courageous actions to defend the Hong Kong dollar against speculative attack and bought stocks to support the market. The many opinions at the time on whether the HKSAR government took appropriate actions created doubts in the minds of the public about the competence of the governing team.90 Secondly, Tung and the civil servants had their differences. He was seen by the seasoned bureaucrats as an inexperienced politician. The civil servants felt Tung did not always listen to them and Tung felt he was not supported. The government appeared poorly joined up and the public blamed Tung Chee Hwa.91 Mainland officials, from Hu Jintao to officers of the Liaison Office, had to repeatedly voice support for him. As Tung’s popularity did not improve, the Liaison Office was asked by Beijing to investigate the reasons for the widespread discontent. The Liaison Office reported that Tung’s problems were mainly caused by the chief secretary, Anson Chan, who had not been fully supportive of him.92 Chan was the quintessential successful “administrative officer”—a generalist class of bureaucrats under the colonial system groomed for the senior ranks. In September 2000, Chan was asked to visit Beijing where Qian Qichen gave her a dressing-down. He emphasised that Chan and the civil service should do better to support the chief executive.93 Anson Chan announced in January 2001 that she had decided to step down and left in April. She later revealed that there had been considerable disagreement between her and Tung:

If you are not able to influence the course of events, particularly events that you very much disagreed with, you must make your choice. So I decided to step down and not be forced out. Mr. Tung and I may not have agreed on how to tackle particular issues. The difficulties were compounded by the introduction of the political appointee system.94

Tung Chee Hwa established a new ministerial system in 2002, where the chief executive would appoint ministers to support his policy direction. Civil servants would then be politically neutral rather than be politicians and administrators at the same time. As with any new system, there were many teething problems with the ministers and how the system functioned. Its implementation did not make governing easier for Tung.95 After Donald Tsang was re-elected in 2007, he appointed mainly civil servants to be ministers and added deputy ministers and political assistants. Questions arose about the need for having yet more layers of inexperienced appointees, how they worked as a team, and their division of responsibility with the civil servants. Tsang also expanded and embedded more administrative officers in the bureaucracy since he believed the supposedly multi-skilled administrators—part of the colonial governing structure—were the ones who would know how to solve problems. Leung Chun Ying relied on both civil servants and external appointees to make up his team. Carrie Lam too had to rely mostly on civil servants as ministers. It was difficult to attract external talent at a time when the political environment was highly charged with officials being frequently vilified and pilloried. While a ministerial system could not solve the problems of legitimacy for the post-1997 chief executives, it did show that the CCP had to accept people from outside the traditional patriotic camp in the creation of ministerial teams. Some of the appointees served more than one term and some were promoted from deputy ministers to ministers. New systems take time to take root and Hong Kong’s ministerial system will no doubt continue to evolve.

There has been little attempt to reform the civil service, led by administrative officers, for Hong Kong to stay competitive and cope with a fast-changing world, including technological, financial, managerial, and communication developments. The highly segmented and stratified bureaucratic structure of the Hong Kong civil service made working across disciplines and departments difficult. The lack of legitimacy and toxic political environment discouraged initiatives that are considered politically “risky”. The speed of getting things done was not helped by extended filibusters in the legislature. Moreover, dealing with the Mainland did not come naturally to the Hong Kong civil service. Speaking Putonghua remains a challenge for many bureaucrats. Not only is the Mainland a very different system, but the People’s Republic of China is also a rising world power with a large and expanding economy with significant research, policy, military, scientific, technology, and innovation capabilities. Beijing has strategies and plans to play an increasingly significant part in global affairs and Mainland officials are ambitious. The HKSAR civil service’s outlook of Hong Kong and its role within the nation and the world seems parochial by comparison.

Another area of discomfort for civil servants is that Beijing takes an intense interest in the HKSAR because it is a part of the nation. In the past, Hong Kong was a faraway afterthought for the British. The attitude of senior civil servants in supporting the chief executive became an issue for Beijing. In May 2017, Politburo member Zhang Dejiang emphasised that Beijing’s “implicit powers” includes “supervising whether [Hong Kong’s civil servants] uphold the Basic Law, and whether they pledge allegiance to the country and [Hong Kong]”.96 This means Beijing has a say in not only the appointment of ministers but also the most senior civil servants in terms of their suitability. In his speech on 1 July 2017 in Hong Kong, Xi Jinping specifically stated that the “awareness of the constitution and the Basic Law” needed to be raised “among civil servants”; and he called upon the Carrie Lam administration, which included the senior bureaucrats, to “advance with the times, actively perform your duties, and continue to improve government performance”.97

United front supporting cast

The CCP’s mobilisation of united front groups when needed has become a part of Hong Kong’s post-1997 politics, such as when the HKSAR government consulted the public or the Legislative Council called deputations on public order or electoral reform issues. The language used and positions adopted were highly similar, which pointed to the likelihood that the CCP machinery played a coordination role. The united front forces include the Hong Kong Island Federation, Kowloon Federation of Associations, New Territories Association of Societies, and the Federation of Hong Kong, as well as a wide range of bodies, such as the Shaukeiwan and Chaiwan Residents Fraternal Association, Hong Kong Federation of Women, Fukien Athletic Club, Youth Executive Subcommittee of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, Hong Kong Federation of Students, Hong Kong Swatow Merchants Association, Hong Kong Clerical Grades Civil Servants General Union, Personal Care Workers and Home Helpers Association, Kowloon Elderly Progressive Association, and Hong Kong Overseas Chinese General Association.98 Scholars estimated that the united front machinery covers more than 600 organisations,99 and it has cultivated as many as 4,000 to 6,000 civic groups over the years.100

Since 2012, the united front legions became more muscular. An early example was the Hong Kong Youth Care Association that went head-to-head with the Falun Gong. For many years, the Falun Gong put up banners and exhibits at street sides frequented by Mainland tourists. In 2013, the Hong Kong Youth Care Association put up anti–Falun Gong banners at the same locations with slogans like “Boycott Falun Gong evil cult”, “Build a harmonious Hong Kong”, and “Taiwan Falun Gong get out of Hong Kong”.101 A recent development was the appearance of a range of new groups to counter the actions of the opposition, including Caring Hong Kong Power, Voice of Loving Hong Kong, Hong Kong Youth Care Association, Hong Kong Justice League, Defend Hong Kong Campaign, Silent Majority for Hong Kong, and Alliance for Peace and Democracy.102 For example, Voice of Loving Hong Kong organised the Love Hong Kong, Support Government rally on New Year Day in 2013 to counter anti-government demonstration organised by Civil Human Rights Front. Silent Majority for Hong Kong was formed in 2013 to oppose the Occupy Movement. The Alliance for Peace and Democracy formed in 2014, which included Silent Majority for Hong Kong, countered the Occupy and Umbrella Movements. The alliance organised signature campaigns, a run for democracy, and a parade. Patriotic groups also got together to denounce the two Youngspiration legislators-elect, Leung Chung Hang and Yau Wai Ching, for their insulting oath swearing in October 2016. The groups called their alliance the Anti-China-Insulting, Anti-Hong Kong Independence Alliance.103 On 29 November 2016, Zhang Dejiang received Silent Majority for Hong Kong in Beijing and praised its efforts.104

Mass Movements and Beijing–Hong Kong Relations

Mass movements in Hong Kong since the reunification have changed Beijing–Hong Kong relations from the initial hands-off attitude to a hands-on approach. Two high-level edicts from Beijing sought to stress what the CCP wanted Hong Kong people to mull over. In effect, the protests and edicts were head-on collisions between Beijing and Hong Kong. Prior to 1997, there was a buffer provided by the British presence. After reunification, there was no intermediary to absorb the impact. Despite the long transition period from British to Chinese sovereignty, the real transition only really started in 1997.

After the 1 July 2003 demonstration, the CCP sent many foot soldiers to Hong Kong to understand the situation. Party leaders had to show support for Tung Chee Hwa and buy time to figure out what to do. By mid-July, a reassessment process was in place with Politburo member Zeng Qinghong leading the review. Heads of the various CCP departments, relevant ministries, the judiciary and military, Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office, and the Liaison Office were all involved.105 By 16 September, Zeng had toured South China to explore ways to deepen the economic interdependence of Hong Kong and Guangdong, after which he summoned Tung Chee Hwa for a discussion in Hangzhou.106 The rising tide of public support resulted in strong wins for the democrats at the November District Council elections, which worried the CCP—the clamour for “double universal suffrage” to be achieved in 2007 and 2008 had to be stopped. A plan emerged. On 3 December 2003, when Tung Chee Hwa went to Beijing to brief leaders on his work, Hu Jintao used the occasion to send a special message couched in a seemingly innocuous news report:

the president and the central government is very much concerned with the development of the Hong Kong political system with a clear-cut but position of principle . . . The central government holds the view that the political system of the HKSAR must proceed . . . in line with the Basic Law.107

In party-speak, the reference to “principle” means the Central Authorities would not give way. Beijing had worked out a chain of actions. The first step was for Tung Chee Hwa to repeat and stress Beijing’s concern in his annual policy address on 7 January 2004.108 He announced at the same time the formation of a Task Force on Constitutional Development with Chief Secretary Donald Tsang as the head. Tsang explained on the same day that:

[t]aking into consideration our duty to uphold the Basic Law, as well as political reality, we believe that we need to first initiate discussions with the Central Authorities before determining the appropriate arrangements for the constitutional review. At the most basic level, this will avoid the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong community reaching different understandings of those Basic Law provisions regarding constitutional development. Such a scenario could cause serious confrontation between the Hong Kong community and our sovereign government. Obviously, we do not want to precipitate such a situation.109

In other words, Beijing had to be consulted first. The Task Force met officials in Beijing from 8 to 10 February 2004 and upon its return to Hong Kong, repeated all the issues once more.110 On 25 February, the propaganda machinery ratcheted up the debate with Wen Wei Po in Hong Kong providing a refresher course on patriotism, as noted earlier in this chapter. Just as the patriotism debate was subsiding, the final piece of the jigsaw was dropped into place. On 26 March, another innocuous-sounding Xinhua news report stated that the agenda of the next SCNPC meeting on 2–6 April was discussed and it would include a draft interpretation of two specified sections of the Basic Law.111 No one had expected such a move. An interpretation was provided on 6 April 2004. The CCP had delivered the final knock-out punch.

National education

When Hu Jintao visited Hong Kong for the tenth anniversary of the reunification in 2007, he stressed the need to put more emphasis on national education. Donald Tsang pledged to do so and announced the development of moral and national education as an independent, standalone subject in his 2010 policy address.112 It would be introduced progressively from the 2012–2013 school year and would become compulsory in primary schools in 2015–2016 and in secondary schools the following year. Tsang’s term ended on 30 June 2012. Leung Chun Ying inherited the launch of the new subject. Three days after Leung assumed office, news broke that a teaching handbook, called The China Model, created by authors with close ties to the Mainland, lauded the CCP as a progressive, selfless, and united ruling party but described the American election system in derogatory terms. The handbook was condemned as political brainwashing. This led to the first mass protest during the Leung Chun Ying era.113

The protest started on 29 July where 90,000 people participated. This was a campaign led by students, parents, and teachers—not the pan-democrats. The organisers did not want their movement to be hijacked by politicians. Large crowds continued to besiege government headquarters for days. The HKSAR government eventually backed down—moral and national education would not be compulsory. The most significant outcome from this period was the emergence of post-90s activists, one of whom, Joshua Wong, became an international celebrity, and another, Nathan Law, ran for legislative election in 2016 and won. Their group, Scholarism, attracted many young members and it was a major force during the subsequent mass movements. By 2014, the youngsters had become seasoned activists. On 10 April 2016, Scholarism transformed itself into the political party, Demosistō, with Nathan Law as its chairman.114 The party promoted self-determination and proposed Hong Kong to hold a referendum in a decade’s time so that Hong Kong people could decide their own fate beyond 2047.115 Leung Chun Ying responded that the HKSAR was an inalienable part of the country with no time limit. He said the phrase in the Basic Law that the HKSAR would “remain unchanged for 50 years” referred to the capitalist system and way of life of Hong Kong—it did not mean that the sovereignty could be changed.116

The young had an irresistible quality and media-attractiveness lacking in tired politicians. They were energetic, fearless, creative, stubborn, self-righteous, and disrespectful of authority. They hated being belittled as ignorant kids. The young, their parents, and teachers were also furious at being labelled as “black hands” of political forces. The energy released from their campaign captured the attention of students, setting the stage for more activism. The national education debate also brought out the fear of political indoctrination of the education system.117 Another strand was mixing political values with “China”. Disapproval of the CCP’s outlook became associated with “China”, “Mainland”, and even “Mainlanders”. Horace Chin captured the mood of the young through his writings. He argued that Hong Kong should become an autonomous city-state.118 The CCP saw these developments in Hong Kong as a dangerous “political duel” between national identity and Hong Kong independence with foreign interference lurking in the background.119 Hu Jintao highlighted the Politburo’s concern at the 18th CCP Congress in November 2012:

The underlying goal of the principles and policies adopted by the central government concerning Hong Kong and Macao is to uphold China’s sovereignty, security and development interests and maintain long-term prosperity and stability of the two regions . . . The central government will also firmly support the chief executives and governments of the two special administrative regions in promoting the unity of our compatriots in Hong Kong and Macao under the banner of loving both the motherland and their respective regions and in guarding against and forestalling external intervention in the affairs of Hong Kong and Macao.120

Xi Jinping repeated that China’s sovereignty, security, and development interests must be upheld when he gave his address on 1 July 2017 at the twentieth anniversary of the reunification. He also emphasised the importance “to raise awareness and enhance guidance, especially to step up patriotic education of the young people”.121 The contrasting attitude between Chinese leaders and Hong Kong parents and students was stark.

Edicts from Beijing

Beijing issued The Practice of the “One Country, Two Systems” Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, a White Paper published by the State Council on 10 June 2014. The paper states that Beijing has “comprehensive jurisdiction” over the HKSAR and can “directly exercises” that jurisdiction. Hong Kong’s autonomy is “not an inherent power, but one that comes solely from the authorisation by the central leadership”. In other words, “a high degree of autonomy” never meant full autonomy and not even decentralised power. It means that Hong Kong only has “the power to run local affairs as authorised” by Beijing.122

Lawyers were particularly sensitive and upset by references in the White Paper to describe judges as “administrators” and having to be patriotic. Some 1,800 lawyers wore black and marched in silence. Judges too had to make sense of the White Paper. Chief Justice, Geoffrey Ma, stressed that judges in Hong Kong acted independently: “and the reality matches this”.123 Judge Joseph Fok noted that the “administration” in generic terms included judges but the judicial oath was clear that judges “administer justice without fear or favour”. Furthermore, he stressed that “the oath of allegiance taken by judges . . . in Hong Kong is not inconsistent with judicial independence”.124

The White Paper was the prelude to another SCNPC decision on electoral reform—Hong Kong could achieve universal suffrage for the election of the chief executive in 2017 with “corresponding institutional safeguards”—a nominating committee to ensure candidates were patriotic.125 Legal scholar Benny Tai at the University of Hong Kong proposed using civil disobedience to pressurise Beijing and the HKSAR government to give way. He named the campaign Occupy Central with Love and Peace.126 University students and Scholarism staged coordinated class boycotts and organised public events, which eventually morphed into the Occupy and Umbrella Movements.127

Since the 1 July 2003 demonstration, the subsequent wave after wave of protests had both toughened the resolve of the Central Authorities, as well as politicised the younger generations in Hong Kong. The moral and national education debate in 2012 penetrated primary and secondary schools. University students and young graduates were the main participants in the Occupy and Umbrella Movements in 2014. Teachers were squeezed between a rock and a hard place since the HKSAR government did not wish to see pro-independence activities at schools while students pushed to be allowed to do what they wanted. Some schools issued internal guidelines to help principals and teachers navigate the minefield. Wang Zhenmin of the Liaison Office said independence debates should not take place in schools because it would “poison” students’ minds.128

Birth of social movements

Over time, a generational change had taken place in Hong Kong, which affected the community’s attitude on many issues. This was evidenced by the heightened public interest in a range of new demands. An important factor that riled the young was the unfairness in Hong Kong society, where income inequality had risen sharply over the course of two decades. Popular causes also related to lifestyle, such as expanding open spaces, walking and cycling, protecting the environment, supporting local culture, and reviving farming. The contours of the “post-80s”, “post-90s”, and “millennial” generations as a political force became clearer after 2007. Generally, they lean towards liberal ideas and are savvy with e-mobilisation methods. For example, they took part in the Anti-High Speed Rail Movement against the Hong Kong-Shenzhen-Guangzhou Express Rail Link. On 18 December 2009, thousands of protesters gathered outside the Legislative Council while legislators debated the funding for the project. The debate had to be adjourned. Protestors gathered at the Legislative Council on 15 January as the debate resumed. The protesters used social media means, such as chat rooms, SMS, Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook, to spread their message and rally people. They used simple but eye-catching means to get media attention, such as doing the prostrating walk (苦行). Funding was approved after 25 hours. Protestors blocked government officials and lawmakers from leaving and delayed their departure for many hours.129 Such activities fertilised young people’s consciousness and gave birth to “localism”.

Law, Order, and Politics

It was bound to happen. The two very different political and legal systems of the Mainland and Hong Kong would clash. The Basic Law was promulgated by China under its constitution. Elsie Leung said, “from 1 July 1997 . . . a page has turned in our legal history. The common law must now operate under the Basic Law.”130 The Hong Kong Police Force had to deal with constant protests, and yet Hong Kong remained one of the safest cities in the world. The Occupy and Umbrella Movements in 2014 and the Mong Kok Riots of 2016 left so much frustration among rank-and-file policemen that they too had to let off steam in March 2017, while judges looked philosophically at their challenges.

An unexpected case

A case that the CCP could not have expected was Jiang Enzhu being sued by legislator Emily Lau. In 1996, Lau took advantage of the new Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance to seek information from Zhou Nan on whether Xinhua Hong Kong held information on her and if so to provide it. It was widely believed in Hong Kong that the CCP had files on many people. The law requires organisations being asked for information to respond within 40 days or it commits an offence. Lau did not receive a timely response, which prompted her to lodge a complaint to the Privacy Commissioner, as she was entitled to do under the ordinance. After the Privacy Commission contacted Xinhua Hong Kong, Lau received an unsigned response that it did not have a file on her. By then, ten months had elapsed. Since a prima facie breach of the law had been established the Privacy Commission passed the case to the secretary of justice, Elsie Leung, for her to decide whether to prosecute. Leung decided not to do so.131 Lau then brought a private prosecution against Jiang. He sought a judicial review to have the case thrown out. The court found Jiang had not committed the offence as he was not in Hong Kong at the time. The ruling provided for Lau to pay Jiang’s costs.132 The CCP no doubt found the case annoying. The interest in the case was its attempt to test the status of Xinhua Hong Kong on the applicability of laws to state organs in the HKSAR, which remains a complex and evolving legal issue.133

Basic Law interpretations