From Skirmish to Scrum

Bruised muscles and broken bones

Discordant strife and futile blows

Lamed in old age, then crippled withal

These are the beauties of football.

Anonymous, 16th century, translated from Old Scots

If you’re searching for the remnants and roots of old ball games—or old anything for that matter—Orkney may be the best place in the world to go looking. A scattering of 70 or so barnacle-encrusted isles and skerries that extend from the northern shores of Scotland into the frigid waters of the North Sea, Orkney is a place where the present can barely hold its ground against the fierce pull of the past—a place where legend still competes with fact, passion with logic, ritual with routine.

Here, cheerfully stubborn and oblivious to the ways of “ferryloupers” from beyond the Pentland Firth, men still gather in cobblestone streets on the coldest, darkest days of winter to play football the old-fashioned way: two large mobs, one sawdust-stuffed ball, no rules, and nearly four centuries of grudges to keep things interesting. Here they don’t play games. They play the Kirkwall Ba’.

The narrow road from the ferry landing on mainland Orkney winds its way through a stark but stunning landscape of treeless hills and rocky coves, interrupted by the occasional small farmstead. Amid otherwise ordinary fields, seaweed-eating sheep rub themselves casually against megalithic standing stones and graze over the top of low burial cairns. Farther along, dominating a high plateau above two shimmering lochs, stands the mystical Ring of Brogar, a 5,000-year-old Stonehenge-like monument made up of 27 massive stones set within a deep circular ditch.

Clinging to the battered coast nearby is the Neolithic village of Skara Brae. Resembling Bedrock, home of the Flintstones, the site’s remarkably preserved stone furniture, including cupboards, dressers, and pre-Posturepedic beds, has earned it the nickname “the British Pompeii.” And at the heart of the island’s Stone Age landscape lies the unassuming grassy knoll containing Maes Howe, a spectacular tomb formed by 30 tons of flagstone slabs stacked like Legos to form a perfect beehive-shaped tomb for Orkney’s earliest chieftains. On the winter solstice, a shaft of light pierces the darkness of the chamber to illuminate the rear wall, an event that draws an annual pilgrimage of New Agers and born-again pagans from all over.

What was a sacred site for the Neolithic people of Orkney was little more than a shelter in the storm for later Viking marauders who sought refuge here in a snow squall in 1153, an incident recorded in the Orkneyinga Saga, an account of the conquest of Orkney and the establishment of a Norse earldom here. Out of boredom or a desire to mark their turf, the invaders scrawled runic graffiti on the walls of the ancient tomb. The 30 or so inscriptions accommodate Viking stereotypes nicely, including such literary gems as “Thorni fucked, Helgi carved,” and “Ingigerth is the most beautiful of all women” (carved, disturbingly, next to a drawing of a drooling dog).

After ruling the isles for nearly 400 years, the Norse handed Orkney over to the Scottish earls in the late 15th century. But Viking influence remains ever-present in place names and in the lilting local dialect, which the Orcadian poet Edwin Muir described as “a soft and musical inflection, slightly melancholy, but companionable, the voice of people who are accustomed to hours of talking in the long winter evenings and do not feel they have to hurry; a splendid voice for telling stories in.”

One popular story still told on winter nights over peat fires, and captured by local historian John Robertson, is of how the unique and ancient ball game known as the Kirkwall Ba’ came to be:

Hundreds of years ago the people of Kirkwall, Orkney’s capital town, were oppressed by a Scottish tyrant called Tusker, named for his protruding front teeth. After years of oppression, the locals rose up in revolt and forced him to flee to the islands. With the people still living in fear of his return, a brave young man stepped forward and vowed to hunt Tusker down, cut off his head, and take it back as proof that their days of misery were over. He went off by horse and soon succeeded in his task. But while returning home with the bloody trophy swinging from the pommel of his saddle, Tusker’s lifeless teeth broke the skin of the young man’s leg. By the time he reached Kirkwall the leg had become infected and he was close to death. With a dying effort, the hero staggered to the Mercat Cross in the town center and threw the bloody head to the people. Grieved at the young man’s untimely death, and riled by the sight of the hated Tusker’s head, the people began kicking it angrily through the streets of town.

This, some say, is why twice a year a crowd of hundreds gathers at the very same town cross to knock each other senseless over a stuffed leather substitute for Tusker’s head, called ba’ in the local dialect. The story may well be apocryphal and revisionist, but it’s as plausible as any other explanation of this unusual rite of excess. Grievances, I would soon come to learn, die slow and hard in Orkney. It’s strangely satisfying to watch all these centuries later as old Tusker still pays the price for his tyranny.

The Kirkwall Ba’ is a rite that for just two days each year, Christmas and New Year’s Day, cleaves the friendly, picturesque port town of Kirkwall down its middle—quite literally—pitting friend against friend, neighbor against neighbor, even family members against each other. Simple to describe, but confounding to understand, the ba’ is a traditional folk football game in which two “teams” of 100-plus men each compete over a homemade ball—also called the ba’—and attempt to claim it for their side, and for posterity.

The sides, known as the Uppies and the Doonies, represent an ancient, almost tribal, division of the town: the upper inland half and the lower (“doonward,” as they say) portside half. Once the ball is thrown up in the town center to the pack of players, the goal of the Uppies is to move it several blocks up the street and touch it to the wall at Mackinson’s Corner. The Doonies, in turn, must take the ball down-street to the port and submerge it in the bay. There are blessed few restrictions on how the ba’ might reach either fate.

In all its unruly and primitive glory, this contest of wills, historians agree, is one of the only surviving remnants of the earliest form of football as it was once played across Europe—long before civilization or regulation got hold of it. As loyal Orcadians would argue, it is football as it was meant to be played. To take some measure of the distance the game has traveled, from rolling heads to aerodynamically engineered balls, and from the dirt lanes and open fields of medieval Europe to gleaming stadiums and neighborhood pitches around the globe, I decided to go to Kirkwall and experience the ba’ firsthand.

When I arrived in Kirkwall on the penultimate day of 2009, a thick ice coated the cobblestone streets. Shoppers tiptoed by with caution, while the winds slicing through the narrow alleys pushed the temperature well below freezing. Scotland was suffering its coldest, snowiest winter in years. The news was filled with reports of road closings and deadly accidents, salt shortages and families stranded for days with distant relatives they’d only meant to visit for Christmas dinner.

In Kirkwall they were still recovering from the recent Christmas Ba’, which had been even more damaging than usual. One ferrylouper had foolishly left his BMW parked on the street, and the pack of 200 or so burly men went right up and over the car, crushing it like an aluminum can. The Uppies and Doonies were still arguing over which side was responsible for the damages.

Most had moved on and were getting ready for Hogmanay, the Scottish New Year’s celebration—and the culmination of the festivities: the New Year’s Ba’. The whir of drills and rapping of hammers echoed across town as homeowners and shopkeepers erected heavy wooden barricades to protect their windows and doors from the violence of the pack.

My first stop in town was at the home of Graeme King, ba’ player and 1998 champion and, at the age of 47, an emerging elder statesman of the game. A big, barrel-chested Viking of a man, Graeme’s girth was nearly double my own. With a crushing handshake, he welcomed me into his sunken living room, where a fire burned next to a highly flammable-looking artificial Christmas tree. Gathered together were two other former champions—Bobby Leslie (’77) and Davie Johnston (’85), who’d been chosen to throw up this year’s ba’ in honor of the 25th anniversary of his win. Also in attendance was George Drever, one of a handful of craftsmen who painstakingly make the ba’s each year.

All four, I quickly learned, are Doonies through and through.

“Right,” asked Graeme before we’d even had a chance to sit down, “which way did you enter Kirkwall?”

“Well, let me see . . .” I recalled, tracing the route in my head. “I took the road up from the ferry landing and then came past the airport and . . .”

Davie sprung up from his chair. “Door’s that way!” he shouted in mock disgust. “Now you’re walking home!”

“Now hold on,” said Graeme, as though arguing before a court. “He was in a car the whole time. More important is where you first set foot in Kirkwall.”

“Well . . . that was at the B&B down on . . . Albert Street,” I answered nervously, confused by the inquisition.

“Safely in Doonie territory!” declared Graeme with relief, slapping me hard on the back.

Once seated, Graeme explained that on ba’ day everyone—players, spectators, outsiders, foreigners—is either Uppie or Doonie. It’s not something you get to choose. You don’t put it on or take it off like a team jersey. It’s predetermined. If you’re a local, affiliation is a matter of where you’re born. If you’re an outsider, it depends on how you enter Kirkwall for the first time in your life. Post Office Lane is the dividing line. Between that line and the shore you’re a proud Doonie; between there and the head of town you’re stuck being a godforsaken Uppie, forever.

“Once you’ve tied your colors to the mast,” Graeme said, “there’s no going back. You can’t say, ‘Oh, I think I’ll be an Uppie this year.’ You are what you are for life.”

I had apparently, by sheer luck of having chosen the right accommodations on the Internet, been spared a fate worse than death.

The origin of the Uppie and Doonie division is believed to date back eight centuries to the founding in the 12th century of St. Magnus Cathedral, the spectacular Romanesque structure that marks Kirkwall’s town center. At that time the town was co-ruled by the Norse earls and the bishop of Orkney. Everyone who lived “down-the-gates” ( gata being the Old Norse term for road) between the cathedral and the shore was considered a vassal of the earl. Everyone who lived “up-the-gates” above the cathedral was a vassal of the bishop. Over the centuries, a deep-seated rivalry emerged and identities hardened around which part of town you were born in. One of us—or one of them.

It’s not hard to imagine that this may not have always been just a friendly rivalry. Violent clashes between the two groups, if they indeed occurred, would have threatened the order and stability of the small island community. In this scenario, the ba’ may have come about as a way to settle conflict and work out differences without suffering the damages of petty wars.

In the tribal divide between Uppie and Doonie we can see the deeper roots of the greatest football rivalries: Real Madrid versus Barcelona, Celtic versus Rangers, Manchester United versus Liverpool. And that’s just association football. American college football is equally famous for its annual clashes, such as Army versus Navy, Harvard versus Yale, and Texas versus Oklahoma, the “Red River Rivalry,” named for the body of water that separates the two states. In fact the word “rival,” which comes from the Latin rivalis, means “someone who uses the same stream as another.” True to the name, a good rule of thumb for rivals is that the closer they are geographically, the more deep-seated the hatred. Of course, most great modern rivalries manage to exploit and exacerbate other divisions along religious, class, ethnic, or political lines. Il Superclásico, the epic derby in Buenos Aires between the River Plate and Boca Juniors clubs, has been cited by the London Observer as number one of the “50 sporting things you must do before you die.” The two teams emerged in the early 1900s in the same working-class portside barrio of Boca, but River Plate moved to an affluent suburb soon after, earning the nickname Los Milionarios along with the eternal enmity of Boca supporters.

Now that I was a bishop’s man and a Doonie, I was determined to embrace my new identity, and at least for the next couple of days I would find good reasons not to trust my Uppie enemies. But I didn’t have to wait that long. As he waxed on about what it meant to be a Doonie, Graeme lamented that since he’d claimed the ba’ for the Doonies back in 1998, they had managed to win just one other time—in 2006. Put in starker numerical terms, over the past decade the Doonies had a pathetic 1–20 record. My newly adopted club was, statistically speaking, a losing franchise. And we weren’t happy about it.

“To be honest, it’s annoying,” said Bobby, a 69-year-old retired librarian who still joins the fray every year against his wife’s wishes and his doctor’s counsel. “The Uppies have had the bragging rights for too long. You can’t walk around with your shoulders high at this point.”

Debate ensued among the men over how they’d become perpetual underdogs. One blamed the construction of the town’s hospital in the late 1950s in Uppie territory. This meant more and more people since have been born Uppies—giving them unfair advantage in a contest determined as much by the size and weight of your team as anything. There have since been more than a few Doonie women who have chosen home birth over the alternative. Due in part to the arrival of the hospital, the convention for determining your affiliation began in the 1970s to shift away from your place of birth toward which side your father and grandfather had played on.

“We go around to the schools now to educate the next generation about the tradition,” said Graeme. “Kids naturally want to be on the winning side. But we explain that’s not how it works. We’ll meet a lad who lives in Uppie territory who’s sure he’s Uppie, but we’ll ask a few questions and find out, ‘Oh, you had a granddad who won a ba’ for the Doonies, did you? Well you’re a Doonie then.’ ” Graeme and his mates were, in other words, in full recruitment mode.

Graeme ducked out of the room and returned with a shining black and brown sphere, which he ceremoniously placed in my hands. “There she is. The sacred orb herself.”

Expecting to see some roughly stuffed and stitched facsimile of a ball, I gasped aloud at the obvious craftsmanship of what I held. Approximately the same size as a soccer ball but three times as heavy, the ba’ is lovingly handstitched with eight-cord flax from top-quality leather donated by a German shoe company. Assembled with eight panels, painted alternately black or brown, and coated with a heavy shellac, the ba’ is crafted not only to survive the punishing pressure of the pack on game day but to live on as the most cherished trophy of the man fortunate enough to take it home. At that moment, I wished Aidan could be there to hold that ball and feel with his own hands the care and artisanry that went into it. It was a thing of beauty.

George, a stocky, bearded 62-year-old whose day job is on a North Sea oil rig, estimates he’s made close to 50 such balls over a 27-year span. Each ba’ takes maybe 40 hours to produce. The stitching alone can take two days. The core is formed from crushed cork that came originally from the packing material in old fruit barrels and today is imported from Portugal.

“Ach, the stuffing is merciless work,” he said, looking at his callused hands. “You leave a wee hole in one of the seams and keep packin’ doon and doon and doon.”

Rumors and accusations still fly that a Doonie ba’ maker will slip a bit of seaweed in the ball or an Uppie a bit of brick from the wall to draw it magically back to its source. When asked if he’d ever attempted such sorcery himself, George pleaded the fifth. “Well, now I’ve heard the same stories . . .”

With a look of impatience, as though my fascination with the ball itself might distract me from the game’s deeper meaning, Davie Johnston, a successful businessman in his late 50s who moved away from Orkney when he was 19 but has returned every year since to play the ba’, leaned in to me and rested his hand solemnly on the ball.

“This isn’t a trophy. This is heritage. This is history. This is tradition. This is what I won and my granddad and his granddad won before me and that’s what it’s about. It goes back that far and that deep. It’s hard to understand the depth of feeling we have for it. It’s huge.”

Despite some recent efforts to trace the murky origins of football to the Chinese kick ball game of cuju or to the Roman game of harpastum, there’s no evidence that those or any other sports of the ancient world had any direct influence on the development of football as it emerged in medieval Europe. Cuju, a game that may date as early as the fourth century BC, became wildly popular in the royal courts of the Han dynasty and eventually spread to Korea and Japan. The game, which resembled modern football in some ways, was described in a poem of the time:

A round ball and a square wall,

Just like the Yin and the Yang.

Moon-shaped goals are opposite each other,

Each side has six in equal number.

The stuffed ball was eventually replaced by one with an inflated pig’s bladder and goalposts replaced gaps in walls as the target. Although the game played an important role in Chinese daily life and enjoyed an impressive run of more than 1,500 years, it never appears to have spread farther than the royal courts of East Asia. And while it’s quite possible that Roman soldiers brought their game of harpastum with them when they invaded Britain, there are no accounts of Romans mixing it up with their subjects on British pitches. As one British scholar has humbly pointed out, harpastum, which involved assigned positions covering zones of play, was a more sophisticated game than early English football. In fact, it would take until nearly the 19th century for football to gain the level of organization and sophistication that the Roman sport—or cuju, for that matter—had achieved by the first century AD.

As scant as the historical record is when it comes to games and pastimes, football as it’s played today can be confidently, if circuitously, traced to early medieval villages of Britain and France. One of the earliest mentions of a football-like game is from the ninth-century Historia Brittonum, a mythologized account of the earliest Britons. In the fifth century, according to the author, Vortigern, a Celtic king from Kent, was attempting to build a tower, but it kept mysteriously collapsing. The king’s sages called upon him to sprinkle the tower’s foundation with the blood of a boy born without a father, so he sent out emissaries far and wide to find such a boy. When they finally located him, he was in the middle of playing an undescribed game of ball ( pilae ludus) with a group of boys. The fatherless child, possibly Britain’s first recorded footballer, grew up to be none other than Merlin, the wizard of Arthurian legend. (Apparently, Harry Potter wasn’t the first young wizard to play ball!)

Coincidentally, the first appearance of the words “ball” and “ball play” in the English language also has an Arthurian connection. Around the year 1200, an account of the festivities surrounding King Arthur’s coronation describes how the guests “drove balls far over the fields,” an ambiguous reference that may or may not suggest a variation of football.

From its earliest appearance, “mob football,” as the game came to be known, was played across England and France as part of festive celebrations, particularly those connected with the feast day known as Shrovetide. Celebrated elsewhere in the Christian world as Fat Tuesday or Mardi Gras, Shrovetide was traditionally the last hurrah of partying and excess before Ash Wednesday kicked in and Lenten fasting and penance began. Originally a pagan springtime celebration, Shrovetide involved a wide range of games and festivities, like bell ringing, cockfighting, cock throwing, and ball games.

What some regard as the earliest record of a football-like game in England is a description of Shrovetide games that took place in London in 1174:

After dinner all the youth of the city proceed to a level piece of ground just outside the city for the famous game of ball. The students of every different branch of study have their own ball; and those who practice the different trades of the city have theirs too. The older men, the fathers and the men of property, come on horseback to watch the contests of their juniors . . .

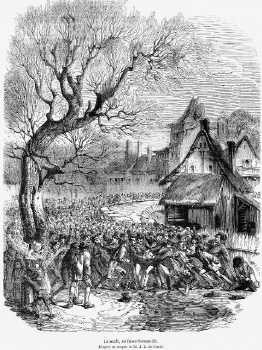

Game of la soule in a village in Normandy, France, 1852.

Around the same time a nearly identical game, called la soule, was just beginning to take off in the villages of Normandy and Brittany. Played with a ball made of leather wrapped around a pig’s bladder or stuffed with hemp, bran, or wool, la soule pitted parishes or villages against each other. Festive games took place at Shrovetide or at Easter, Christmas, or parish patron saint days. As with other variations of mob football, there was no limit to the number of players and no rules to speak of, with play involving huge violent scrums and chaotic melées. The goal, as in the ba’, was to capture the ball and force it back to their home village, submerging it in a local pond to win the game. Some games ritualistically pitted married men against single men. One game in the town of Bellou-en-Houlme was reported to include 800 players and 6,000 spectators! After the games there would be the medieval equivalent of tailgate parties, with drinking, dancing, and carousing well into the evening. The game’s early popularity in France is suggested by a deed from 1147 in which a lord specifies the settlement of a debt with the delivery of “seven balls of the largest size.”

La soule and other forms of football were played not just for the sake of recreation but as magical rites to promote fertility and prosperity—thus the deep connection with Shrovetide and the arrival of spring. In his classic study of European mythology, The Golden Bough, J. G. Frazer interpreted early ball games as contests in which capturing the ball would ensure a good harvest or a good fishing season. In some villages in Normandy, for example, it was believed that the winning parish would secure the better apple crop that year. Another theory, put forward in 1929 by W. B. Johnson, is that the spherical ball for many early civilizations symbolized the sun. The captured ball represents the sun brought home to promote the growth of crops. The word soule, some linguists believe, may in fact derive from sol, the Latin word for sun.

In Orkney, there are similar long-standing beliefs that a win for the Uppies means a good potato harvest, whereas a win for the Doonies means the fishermen can expect a bountiful run of herring. To this day, Uppies will tell you that the potato blight that brought famine to the islands in 1846 began when the Doonies won the ba’ that year and continued until 1875, when the Uppies finally broke their losing streak. That year, an old man was heard to comment, “We’ll surely hae guid tatties this year, after the ba’s gaen up.”

It was just past noon on New Year’s Day when the first spectators began to assemble on the sandstone steps of St. Magnus Cathedral. They staggered out of doorways and alleys, bundled in thick overcoats and shielding their tired eyes from the sun cresting above the glazed rooftops. The whole town, myself included, was still shaking off the dog that bit us at the previous night’s Hogmanay festivities, highlights of which included the requisite bagpipe brigade and the ceremonial passing of countless bottles of Famous Grouse. I staked out a choice spot along the cathedral wall next to the Mercat Cross—the spot from which the ba’s been thrown up for the past 200-plus years.

The sound of battle cries soon emerged from Albert Street as the Doonie players marched up from the waterfront—70 or so men of all ages, from 16 to 70, ready to do their part to tilt the cosmic balance back to the sea. The uniform of choice was a favorite, game-worn rugby shirt, a pair of old jeans, and steel-toed work boots. Experienced players had duct-taped their jean bottoms to their boots to deny their opponents a good handhold during the scrum. From the opposite side of town, down Victoria Street, came the Uppie contingent, prepared to push their supremacy into a new decade. Though deadly serious, the effect was pure theater—the Sharks and the Jets ready to rumble.

Reaching the cross first, the Doonies locked themselves into a tight mass, arms raised above their heads or placed around their mates’ shoulders to keep them free to catch the ba’. Graeme stood up front taunting his opponents good-naturedly as they infiltrated and jostled for position like solid and striped billiard balls arranging themselves for the break.

Davie Johnston appeared from inside the cathedral with the ba’ nestled safely in the crook of his arm and strode proudly to the base of the town cross. He was dressed to play, ready to jump into the fray right behind the ba’. He greeted teammates and surveyed the crowd below that had swelled to several hundred and filled in on all sides of the players. As the clock on the church tower inched toward the traditional hour of one, people began to whistle and cheer with anticipation.

“Go Uppies!” “Come on, Doonie boys!”

With the first loud clang of the church bell, Davie held the heavy ball high and lobbed it into the street below.

Arms shot up as the ba’ was caught and instantly swallowed into the deep maw of the pack. The scrum surged and heaved as the two sides tried their best to gain first ground. Old codgers who in years past would have been in the eye of the storm ran around the outside where they coached and rallied their sons and grandsons.

The ba’ is thrown up to the pack.

“Push now! Come on, more weight around this side!”

Players rotated in clockwork formation from the front to the back of the pack to push up- or downtown. Two-hundred-and-fifty-pound men leaned in on all sides at 45-degree angles, imposing a crushing pressure on the pack’s center.

Then, either the ba’—no longer visible—moved or the weight of the pack shifted, sending the players crashing into the church wall. Spectators gasped and scurried back, some slipping on the ice that coated the grass above. As the men mashed themselves into the wall, one was lifted off his feet by the pressure and squeezed up and over the horde, feet in the air, tumbling out onto the grass. He stood up, wiping blood from his chin, and dove back into the pack, surfing the top of the mob until he sank back in. For 20 minutes, the pack moved no more than a few feet in either direction.

Several ferocious-looking wives circled the edge of the pack like wolves, riling and harassing their husbands, “Come on, Uppie men! Push harder!” It appeared to take all their restraint not to jump in themselves, which they’ve been known to do on occasion. A newspaper report of the 1866 Christmas Day Ba’ describes a moment in the contest when the ba’ was heading up-street and “an Amazon who ought to have been home with her mamma caught it and threw it down.” In the 1920s an Uppie player was said to have run the ba’ through the front door of his house and handed it off to his wife, who hid it under her petticoat. Once the pack of players had moved on, leaving shattered crockery in their wake, she walked unnoticed right to the goal and won the day. Despite playing a vital supporting role, though, the only time women played a ba’ exclusively was toward the end of World War II, when many men were off at war and the women felt empowered to have their own game. The new variation was not well received by the traditional men of Orkney, however, and was soon shut down. One reporter expressed some relief that there were few injuries among the participating ladies and that the “casualties, for the most part, were confined to permanent waves, hats, scarves, shoes, and stockings.”

I was standing about ten feet back from the pack—at a safe distance, I’d thought—fiddling with my camera when I heard, “It’s going down!” The pack split open and a human stampede was coming my way. I held my arms to my sides, sucked my weight in, and did my best imitation of a lamppost while 100 or so men thundered past me on either side, knocking me back and forth. A Doonie player had made the break and gained a block before the Uppie pack caught up and tackled him. But just before his face hit the cobblestones he managed to pass the ball off to a spectator, Nigel Thomson, a veteran Doonie sprinter who’d won school medals in the 400 meter. Before anyone knew what had happened, Nigel was dashing toward the port in his winter coat and Russian fur hat with a mob of angry Uppies in hot pursuit.

As I turned and ran with all the other spectators, a Red Cross volunteer caught up to me, my notebook—now sporting a dirty shoeprint—in her hand.

“Mind yerself now,” she cautioned. Nearby a disheveled young woman was hopping about on one foot searching for the shoe that had been ripped off in the frenzy.

I reached the pack several blocks away. The Uppies had caught Nigel and forced the ba’ out of Albert Street into a narrow side street, or wynd, as it’s known here. The move was a blow to the advancing Doonies, slowing their momentum and cutting them off from their main route to the sea. In the heat of the ba’, Graeme had assured me, what appears to the observer as a random move by a mindless mob, is usually quite deliberate and strategic. Knowing every wynd, nook, and cranny between here and their goal, the Uppies would now be mapping the route that would give them the best advantage.

The pack had plugged up the ten-foot-wide wynd like a stopped-up drain. I watched as one player’s back was smashed against a pipe. Arms above his head, he winced, pushed, and wriggled to create more space to breathe. Doonies ran around the back to reinforce and push the ba’ back toward the main street, while the Uppies did the opposite. The effort, in either case, was useless. With occasional counts of “One, two, three . . . heave!” the pack would surge a few inches in one direction or the other but with little change in position. I spotted Graeme’s bald head bobbing up in the thick of the scrum. At his age, and having won his ba’ years ago, I’d have thought he might retreat to the perimeter and let younger men take the brunt of it. But there he was at ground zero.

After my last brush with near death, I planned my own escape route down a side alley strung with clotheslines should the pack break suddenly in my direction again.

Watching the gridlock in the alley, it struck me that this game is as much about moving the pack as it is about moving the actual ball, which had been out of sight since Davie first threw it in over an hour earlier. Finally, there was a ruckus and hollering up ahead. A break was on, mercifully not toward me this time. The Doonies were on the move again. They’d forced the ba’ back to the corner of Albert Street and a fierce struggle was on in front of the Frozen Food Grocers. I watched fists fly and bodies hurl against the thick wooden barricade bolted into the window frames, the only thing standing between the men and freezers full of ’nips and tatties (turnips and potatoes, the national vegetables of choice). Parents with small children backed away cautiously, anticipating the worst. The pack made a turn toward the water and began to bounce its way along stone walls and shop barricades. But the Uppies managed to force the ba’ off the main street once again—this time into a six-foot-wide dead-end alley between the local bank and photo store.

Fewer than half of the players could squeeze into the alley. Several young players ran around the back of the building, shimmied under a low driveway gate, propped a Dumpster against a wall, and scrambled onto a flat roof overlooking the alley.

One Doonie surveyed the scene below and reported out to his mates and supporters, “The Uppies have it wedged under a staircase.”

A more seasoned player, clearly upset with this turn of events, shook his head and scuffed his boot on the ground, “Ach, it’ll be in there a good long while now.”

As though on cue, an icy drizzle began. Umbrellas came out and hoods went up as spectators and players alike settled in for a long “hold,” as they refer to periods when the ba’s movement gets shut down. Several Red Cross medics came running down the street. One of the players in the alley had passed out from lack of oxygen. A few men heaved against the gate blocking the entrance to the roof until the latch gave way. The medics rushed in and were waiting for the man to be handed over the roof when a red-haired lad ran over.

“It’s okay, he’s woken up!”

It was now 3:15 and, being just 50 miles of latitude south of Greenland, the midwinter darkness was already settling in. As the Christmas lights flickered on and the drizzle gave way to a lashing hail, the madness of it all came over me. I was standing outside a miserable gray alley with hundreds of other people, soaked to the bone and shivering, watching grown men risk life and limb to get a ball out from under a staircase. It was irrational, utterly pointless, and absolutely thrilling.

Did the ball first evolve from stone projectiles used by early man in the hunt? Or was it a symbolic stand-in for their prey—the object rather than the weapon of pursuit? Back in Europe’s Paleolithic days—long before Maes Howe and Skara Brae were built—hunters from competing bands followed and tracked the same herds across plains and forests without reference to boundaries or territories. The band that was fastest and strongest and smartest won the day. And the hunter who led the way and outsmarted both prey and challengers was hailed as a hero. As depicted in the dramatic cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira, magic was conjured and rituals were conducted—whatever it took to tilt the balance in favor of the home team.

The rise of agriculture roughly 10,000 years ago may have shifted the nature of the pursuit—from a good hunt to a bountiful harvest—but it didn’t change the nature of the battle. Whichever tribe or village secured and could defend the best land and most reliable water supply would have the best chance of surviving the long, cold European winter. For agricultural peoples, magic and ritual focused on attracting and capturing the sun and the rains. As populations grew and prime land became scarcer, boundaries were drawn and defended and competition grew fiercer and more violent.

It’s hardly a stretch to suggest that the metaphors that still resonate most in describing football, and other competitive sports—the team “on the hunt” for the championship, “hungrier” than their opponents, “battling” and “claiming territory”—are more than mere metaphors. They’re collective memories of when games also served as fertility rites and when the ball symbolized the hunter’s prey or the farmer’s sun—when the stakes of winning or losing were, quite literally, life or death.

The Kirkwall Ba’ is a holdover from the earliest forms of football in so many respects—the near absence of rules, lack of boundaries, and large, moblike teams, to name just a few. But one element that stands out as being truly premodern is the goal of the game itself. Whereas the object of modern football, and most other ball games that have survived, is to drive the ball into enemy territory to penetrate the defended goal, the object of the ba’ is quite the opposite: to capture the ball and take it home.

It’s tempting to see in the ba’ a survival of the primitive magic of the hunt and the rituals of early farmers directed at claiming the prize—and the sustenance it offered—to ensure survival. The association of early football and the French la soule with Shrovetide fertility rites, and the ba’s association with the winter solstice, supports this deep, primal connection. Over time, competition became less about survival and more about capturing territory and amassing political power. The focus of ball games shifted from capturing the prize to simply attacking and defeating the enemy—an elaborate means to an end rather than the end itself. And the “goal” became to overrun the enemy’s defenses, to score against and dominate them.

However accurate a picture this may be, there’s little question that the physical violence of the ba’—and the tenuous restraint of violence found in its modern variations—is fundamental to the game and its origins.

Some of the very earliest records of football are accounts of fatal accidents that occurred in the heat of the game. In 1280, a friendly Sunday afternoon game of what appears to be football in the Northumberland region of England turned deadly when one player running toward the ball impaled himself on the (supposedly sheathed) knife of his opponent and, as the witness described it, “died by misadventure.” In 1321, apparently before players figured out that knives and football didn’t mix, another identical “death by sheathed knife during football match” was reported that led to the acquittal of the perpetrator, a church canon, by Pope John XXII.

And just as violence and murder found their way into otherwise innocent matches, football seems to have brought occasional inspiration to otherwise mundane acts of homicide. In the same year as the church canon’s knife incident, two brothers were convicted for murdering the servant of a monastery and then playing football with the victim’s head!

Like the Kirkwall Ba’, medieval folk football in Britain was a consistently rowdy and violent affair played mostly by commoners in the open fields of country villages or in narrow city lanes. As with the Uppies and Doonies, everyone was invited to join the mayhem—young and old, men and women, even clergy. As an observer of the time noted, “Neyther maye there be anye looker on at this game, but all must be actours.” Is it possible that the violent hooliganism that’s plagued modern football in recent decades reflects a submerged desire on the part of frustrated supporters to reclaim their historic right to join the scrum? That the poor skull crackers just want their go at the ball?

Mass games played on Shrove Tuesday or other holidays—fueled by mead and beer—would wreak havoc and leave a path of destruction in their wake. By 1314, when the word “football” first appears unequivocally by name in the historical record, its reputation for inciting violence was already widespread. That first mention, in fact, is from a “Proclamation Issued for the Preservation of the Peace” on behalf of Edward II banning the game within the limits of London:

Whereas our Lord the King is going towards the parts of Scotland, in his war against the enemies, and has especially commanded us strictly to keep his peace. . . . And whereas there is a great uproar in the City, through certain tumults arising from great footballs in the fields of the public, from which many evils perchance do arise—which may God forbid—we do command and do forbid, on the King’s behalf, upon pain of imprisonment, that such game shall be practiced henceforth within the city.

In the century following that first reference, football was banned by English monarchs nine times. The French kings and clerics followed suit with their equally excessive game of la soule. In 1440, a French bishop called for a ban on that “dangerous and pernicious [game] because of the ill feeling, rancor, and enmities, which in the guise of recreative pleasure, accumulate in many hearts.”

But while the violent nature of the game clearly served as the outward rationale offered for these prohibitions, a closer read of the records suggests something else was at work. The sports of choice for noblemen of the times were those of the medieval tournament—jousting, fencing, and archery—all viewed as practical exercises that prepared men for battle. Time spent kicking balls around fields was time taken away from archery, which the common men were required to practice so they’d be ready to defend the kingdom. Football and other games were seen as “useless and unlawful exercises.” In 1365 Edward III insisted that “every able-bodied man” in London “shall in his sports use bows and arrows or pellets or bolts” and forbade them “under pain of imprisonment to meddle in the hurling of stones, loggats and quoits, handball, football . . . or other vain games of no value.”

All prohibitions, on either side of the Channel and whatever their motivation, were of course duly ignored by the fun-loving masses, and football and other “useless” games lived on. As William Baker summarized the stubborn determination that allowed football to survive into the modern era: “In the face of moral preachments and official decrees, English common folk refused to relinquish their games. Even with the passing of feudalism they had few rights, but apparently considered their freedom to play as an integral part of their birthright.”

It was 4:00 PM and the residents of Kirkwall were actively exercising their birthright under a cold, lashing rain. Several more players had since passed out and been revived, but the ba’ remained stubbornly tucked under the stairs in the alley behind the photo store—exactly where the Uppies had taken it nearly two hours earlier. Touched by boredom, I walked around to survey the scene from the main street. Silhouetted against a backdrop of flickering security lights, steam rose off the pack of men who plugged every crevice of the alley. It was hard to tell one player from another amid the tangle of arms and legs and rugby stripes.

I spotted a historic plaque on the wall alongside the alley. The ba’, it seems, had eerily settled just a few feet from the site of St. Olaf’s Church, built in the 11th century by Rögnvald Brusason, one of the first Viking earls of Orkney. A sandstone archway is all that’s left of the original chapel. The plaque notes that human remains were uncovered here some years ago and reburied just beneath the alley’s flagstones. It occurred to me that some of the players might be joining their ancestors in Valhalla if they didn’t get out of there soon.

Just then I overheard a spectator utter the magical words, “That’s it, I’m off to the pub!” Unable to feel any of my extremities at that point, I regarded the suggestion as a spark of genius. I followed my new friend to the waterfront and climbed over the barricade protecting the entrance to St. Olaf’s Pub. Half the town (the smart half ) seemed to be inside the jammed bar. I ordered and quickly tossed back a shot of whisky, asking the bartender if I was at risk of missing any of the action.

“Not to worry,” she said. “When they get out of that alley, you’ll bloody well hear about it.” I ordered another shot, which she poured into a plastic cup with a wink.

Taking the cue, I climbed back over the barricade and headed up the street with my new layer of insulation in hand. From the position of the crowd, I clearly hadn’t missed a thing, though there was some stirring up ahead. Minutes later a guttural roar went up as the pack shot out of the alley like a cork fired from a champagne bottle. They broke toward the harbor. The Doonies were on the go again! My heart raced as I bounded toward the water with the crowd behind the ba’. Was it going all the way?

We caught up to the pack on Harbour Street, just a hundred feet now from the water’s edge. Small fishing boats bobbed in the choppy surf nearby. A fierce battle was on against the windows of St. Olaf’s, where we’d just been drinking.

The chants began, “Doonies! Doonies! Doonies!” An upset was in the air and the Uppie supporters confirmed it with their silence. For another 30 minutes or so, the pack thrashed about the waterfront. A boy was thrown hard to the sidewalk and the medics stepped in. The Uppies weren’t going down without a proper fight.

Then it happened. The final break, by a fellow named David Johnstone. Not, it turns out, our man Davie who threw in the ba’. And not the legendary David Johnstone who years earlier had his glass eye turned backward in the heat of a ba’ contest. But yet another David Johnstone. He was on his knees in the crush of the scrum, I learned later, with the ba’ in his hands when a gap appeared portside. He reached out and threw it hard. That’s when I spotted it, sailing above the heads of the crowd and clearing the iron rails at the harbor wall, where it splashed into the waters of Kirkwall Bay.

A cheer went up from the crowd as four Doonie men dove into the black, icy waters after the prize. There, by the water’s edge, was an ecstatic Graeme calling to his younger teammates, “If you’re claiming it, get in there!” The Doonies had won the ba’ and broken their long drought. Now the battle was on to see who would take home the “sacred orb.” I pushed my way through the crowd and peered over the harbor railings. In the dark, I could make out traces of four or more players tussling in the water as each tried to climb up the seaweed-covered ladder with the trophy. The ba’ finally made its way up to the street and through the crowd with several men grappling for it the whole time.

“Norman’s ba’!” called out a young woman in the crowd. “Ronald’s ba’!” cried another. Other voices joined in, offering the names of other players who they felt deserved the honor.

As Davie had explained to me two nights earlier, the winner of the ba’ isn’t simply the player who ends up with it, or even the one who fought the hardest that day. Just as you can’t choose to be Uppie or Doonie, you can’t expect to have a lucky day and walk away with the prize of a lifetime. The winner is the man who’s showed up year after year in the hail and the ice, who’s had more ribs broken in the thick of the scrum than he can count, who’s given up his Christmas Days and New Year’s Days year after year for the love of this crazy game. As Davie had enacted the real-time negotiations for me as they were playing out among the Doonies at that moment, “Did he play in other ba’s? Did he help out his teammates? Did he ever miss a ba’? What was his attitude when he was losing?” Within five minutes, every part of your past will be dredged up on the spot.

Finally, after nearly an hour of heated debate and scuffling, one man was hoisted above the mob with the ba’ over his head. Forty-seven-year-old veteran Rodney Spence had won the honor. After five hours of play, the ba’ would go home with him, along with 300 or so players and spectators for whom he’d have to host a raucous all-night party. Rodney would, for the rest of his life, have on his fireplace mantel the greatest prize any Orkney man could ever hope for. The Doonies would hold their heads high in town once again and would enjoy bragging rights for at least another 51 weeks. And the fishing, quite possibly, would be the best it’s been for years.