The Creator’s Game

There are two times of the year that stir the blood:

In the fall, for the hunt, and now for lacrosse.

Oren Lyons Jr., faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation

It’s May 22, 2009, at the New England Patriots’ stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, and another, much older contest has taken over the gridiron: the NCAA lacrosse championship. Two powerhouses, Syracuse and Cornell, have been pushed to “sudden victory” overtime by an improbable fusillade of goals by the Orange in the final minutes of regulation. Cornell wins the face-off and gets it to one of their top scorers. Syracuse defenseman Sid Smith checks him hard, strips him of the ball, and works it quickly down field to his best friend, attack man Cody Jamieson. Jamieson winds up with a left-hand shot so perfect, so routine, that he never had to look back to know it went in.

Having just clinched the championship, Jamieson, a Mohawk Indian, turns and charges 80 yards upfield, stick over his head and a trail of white-and-orange jerseys in jubilant pursuit, to embrace Sid, a Cayuga Indian whom he’d grown up with on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ontario.

It was a moment that, by all reasonable odds, should never have taken place. That Syracuse should pull off its 10th NCAA championship win was historic but not surprising. What defied the odds was that an American Indian game banned by early missionaries as “sorcery” should have hung on through four centuries of disease, genocide, and warfare. Lacrosse, which had patiently infiltrated the white culture that nearly extinguished it, had now arrived at the point where it could be played live on ESPN in front of 68,000 fans: this was truly remarkable. Decades after their great-grandfathers had been barred from playing their game, two young men of the Wolf Clan of the Iroquois League shared a victory that, save the efforts of their determined ancestors, could quite easily never have occurred.

But lacrosse is a survivor.

By AD 800 ulama had worked its way across the Rio Grande, influencing the development of a short-lived rubber ball game in ancient towns throughout Arizona and New Mexico. The long-distance running Tarahumara people played a kick-ball game, called rarajipari, across the deserts and canyons of northern Mexico. Shinny, a popular stick-and-ball game similar to women’s field hockey, brought women and men out to play in villages from California to Virginia. And many Indian tribes, from the Inuit of Alaska to those encountered by the first Pilgrims, had their own versions of football. The game of pasuckuakohowog, played by 17th-century New England tribes, for example, involved hundreds of villagers kicking an inflated bladder across a narrow, mile-long field. It was not all that different, the Pilgrims noted, from their own football.

Few of these games are still played, and some are remembered only by archaeologists and museum curators. Some live on in tribal legend or tradition—preserved and reenacted but long divorced from their vitality and cultural relevance. Then there’s lacrosse, one of the fastest-growing sports in the world.

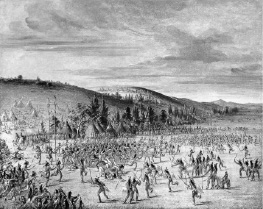

At the time of European colonization, lacrosse was played in one form or another from the western Great Plains to the eastern woodlands and as far south as Georgia and Florida. Despite variation from one region to the next the game was everywhere essentially the same. Teams of up to several hundred men would face off across an open field, often oriented to the cardinal directions, which could stretch for a mile or more in any direction. The only boundaries recognized were natural ones—a rocky outcrop, a stream, a dense stand of trees. Using carved wooden sticks terminating in a pocket made from either wood or woven strips of leather or animal gut, players competed over a stuffed animal-skin ball or one carved from the charred knot of a tree. Through a run-and-pass game they would attempt to score points by hitting a single large post or passing it through a goal formed by two upright posts. Games were known to last for hours or days depending on their purpose and importance.

Three types of sticks were used, representing three different regional traditions, each with its own rules and techniques. The Ojibwe, the Menominee, and other tribes of the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi played with a three-foot stick that had a small, enclosed wooden pocket. In the southeast, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw played a variation of the game using a pair of small sticks with enclosed webbed pockets with which they trapped the ball. In the Northeast, the tribes of New England and the Iroquois Confederacy played with a four-foot stick whose crook-shaped head formed a large webbed pocket.

This crook-shaped stick was first encountered in the early 17th century by French Jesuit missionaries living and spreading the Gospel among the Huron Indians, who lived in palisaded villages just 100 miles or so north of where Cody and Sid grew up. The “Black Robes,” as the clerics were known to the Indians, called the stick la crosse, using a term that the French of the time seem to have associated with any game played with a curved stick. As early as 1374, in fact, a document refers to a stick-and-ball game played in the French countryside called shouler à la crosse. In The Jesuit Relations, a series of field reports the priests sent back to their superiors, Father Jean de Brébeuf provides the first written account of the game, describing with obvious displeasure the association of this stickball game with ritual healing: “There is a poor sick man, fevered of body and almost dying, and a miserable Sorcerer will order for him, as a cooling remedy, a game of crosse.”

A more detailed description of early Indian lacrosse comes from Baron de Lahontan, a French explorer who in the 1680s was given command of Fort Joseph, a military outpost on the south shore of Lake Huron. Like many other tennis-crazed European explorers of the time, he couldn’t help but compare this very different team racket game with the one he had quite likely played back in Paris:

They have a third play with a ball not unlike our tennis, but the balls are very large, and the rackets resemble ours save that the handle is at least 3 feet long. The savages, who commonly play it in large companies of three or four hundred at a time, fix two sticks at 500 or 600 paces distant from each other. They divide into two equal parties, and toss up the ball about halfway between the two sticks. Each party endeavors to toss the ball to their side; some run to the ball, and the rest keep at a little distance on both sides to assist on all quarters. In fine, this game is so violent that they tear their skins and break their legs very often in striving to raise the ball.

Brébeuf and his fellow clerics sought to understand the Indian culture, games included, so they could spread a native form of Catholicism. Although they shared with their earlier Spanish counterparts in Mexico an unwavering mission to convert the “heathen” Indians, the French had a kinder, gentler, and more laissez-faire approach to colonization. As the 19th-century historian Francis Parkman characterized the difference, “Spanish civilization crushed the Indian; English civilization scorned and neglected him; French civilization embraced and cherished him.” The French, whose interests in the New World were largely commercial and centered on the lucrative fur trade, were more likely than the English or Spanish to establish cooperative trade relations and military alliances with the Indians and to recognize tribal rights.

For the Iroquois, Creek, Cherokee, and other tribes, lacrosse was a surrogate for war—“little brother of war” as some Indians called it—and shared much of the same symbolism. Lacrosse sticks and even players’ bodies were sometimes painted with red war paint before important games. In a Creek legend uncovered by historian Thomas Vennum, a father hands his son a war club and sends him into battle, saying, “Now you must play a ball game with your two elder brothers.” Ball games not only served as an important proving ground for young warriors training for battle, but, as lacrosse historian Donald Fisher points out, also provided a diplomatic means of building alliances and avoiding war with neighbors. Ceremonial games brought tribes together to mend political bonds and settle disputes, shoring up tribal confederacies that might otherwise have fallen apart over time. In this way, the Iroquois Confederacy used lacrosse to help establish itself as a dominant military power in the eastern United States and Canada in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Ball play of the Choctaw—Ball Up, 1846–50, George Catlin.

In 1763, a group of Ojibwe and Sauk Indians staged a game for the British troops at Fort Michilimackinac in what is now the state of Michigan and succeeded in merging the sport almost seamlessly with war. With the defeat of the French in 1761, the outpost and trading depot had been handed over to the English, whose poor treatment of the Indians provoked the movement known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. In honor of the king’s birthday, the Indians offered to entertain the English with a game just outside the walls of the fort. The English were kicking back and enjoying the “savage” game, different as it was from their football or tennis, when one of the players fired the ball through the gates of the fort. The warriors rushed into the fort after the ball, traded their lacrosse sticks for weapons that their women had hidden under blankets, and proceeded to massacre the British troops inside. They seized the fort and held it for a year, using their position to extract demands from their new overseers.

As bad as English occupation was for the Iroquois and other eastern Indians, the American Revolution proved to be even worse. The Americans, intent on controlling and expanding their young republic, drove many Iroquois off their lands and into Canada, dividing the Confederacy and initiating a long period of rapid cultural decline. But lacrosse, stripped of some of its religious meaning and importance, hung on and gathered new fans among Canadians and Americans alike. In the years following the revolution, games of lacrosse were recorded in Ontario, played between relocated Mohawk and Seneca groups in an effort to build new alliances. In the 1830s, George Catlin exhibited his romanticized paintings of the “vanishing” Indian, which included depictions of Choctaw Indians playing lacrosse in Oklahoma. In 1844, the first game recorded between Indians and whites took place in Montreal. And just 25 years later, a mere century after the massacre at Michilimackinac, it had been reinvented as the national game of Canada.

Onondaga is the place, I was told. I’d called tribal representatives and the heads of lacrosse programs at several of the other Iroquois nations. If I wanted to learn about the roots of lacrosse, they all told me, the Onondaga Nation is the place to go. “Lacrosse is practically a religion up there,” according to one Oneida Indian I spoke with.

Located just seven miles south of the Carrier Dome, home to the Syracuse Orange, 10-time NCAA Division One champions, Onondaga is a kind of spiritual center and pilgrimage site for anyone looking to worship at the altar of lacrosse. With a population of just 2,000 or so people, the nation has over the years contributed five players to the Canadian Hall of Fame and one to the U.S. Hall of Fame and has fielded more All-Americans per capita than any other community in North America.

For a month or so I’d traded phone calls and emails with Freeman Bucktooth, coach of the Onondaga Redhawks, the nation’s team that competes in the Canadian-American box lacrosse association. Freeman played for Syracuse and was captain and lead scorer for the Redhawks for more than a decade. He’s also raised and trained four lacrosse-playing sons, including two-time Syracuse All-American Brett Bucktooth. When we spoke, he was gearing up for a trip to Manchester, England, to assistant coach the Iroquois Nationals at the World Lacrosse Championships. The Nationals, an all-Iroquois field lacrosse team that includes seven Onondaga players, was ranked fourth in the world. This, said Freeman, was their year to challenge the U.S. and Canadian national teams for the world title. I wished him luck and told him I’d help him celebrate in a few weeks once they’d returned to Onondaga.

A week later, seated in an airport lounge, I looked up at the TV and there was Freeman being interviewed on CNN. The caption scrolled across the set, “We’re lacrosse players, not terrorists.” The team had been prevented from boarding a plane at JFK bound for England because their Iroquois League–issued passports did not meet post-9/11 security and technology requirements. They’d been traveling on these passports without trouble since 1977. Times had changed.

I shot an email to Freeman to show support. The response came back within minutes: “Thanks. It’s not looking good.”

In the days that followed, the team made international headlines as they holed up in a Comfort Inn and played scrimmages with local New York City teams. Federation officials met behind closed doors with U.S. immigration officers. Film director James Cameron offered to donate $50,000 to help pay for extra travel expenses. Opposing teams already competing in Manchester expressed disappointment and outrage. “We’re playing their game,” commented the American coach of Team Germany in an interview. “And our politics denied them the ability to participate in their game. Just terrible.”

At the 11th hour, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton intervened to give the team a one-time travel waiver. But the British government refused entry. They missed the tournament and the United States went home with the gold.

If you get distracted driving south on I-81 out of Syracuse, you can easily miss the exit for the 11-square-mile patch of land that constitutes the Onondaga Nation. One green-and-white exit sign hardly seems to do justice to an entire sovereign nation, but that’s what’s left after 200-plus years of failed or broken treaties and what the Onondaga describe as a history of “illegal takings” of land by New York State. Small as it is, however, the Onondaga Nation remains sovereign, independent, and proud. The “People of the Hills,” as their name translates, pay no state or federal income taxes, receive no subsidies or oversight from the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, and recognize traditional Iroquois law, which predates and some say influenced the U.S. Constitution. One of the Six Nations along with the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Seneca, and Tuscarora that make up the Iroquois League, the Onondaga are considered the “Keepers of the Fire” and the traditional center of the League.

When I made the long drive to Onondaga, Aidan had just begun playing lacrosse for the first time. To me, it was still a foreign game and I was hungry to learn more about it. No one I grew up with ever played it, and only my friends who went to prep schools and elite northeastern colleges had any connection to the game. But watching Aidan and his team play was riveting and made me realize what I’d been missing out on. The tribal roots of the game were unmistakable as sticks clashed, helmets connected, and kids piled up in heaps on the ground: this was a warrior’s game.

Just off the exit, the Onondaga lacrosse stadium looms large, by far the biggest structure on the nation. I slowed down in an attempt to scan the mouthful of a name that emblazons half the width of the building: TSHA’HON’NONYEN’DAKHWA’. It means “where they play games” in the Onondagan language. Literal, but fitting, I thought, for the site where they play the game they call deyhontsigwa’ehs, “they bump hips.” No ambiguity there, though I’ve watched enough lacrosse to know there’s a lot more than hips getting bumped. The $7 million, 2,000-seat stadium, built in 2001, is decorated in purple with two wampum belts: one represents the five original Iroquois nations, the other their peaceful coexistence with the non-Indian society around them. As I got up to the stadium, I found myself stuck in a traffic jam. Was there an afternoon game, I wondered?

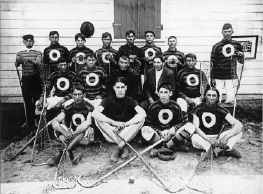

The cars, it turned out, were filled with smokers dismally lined up to get their nicotine fix tax-free at the nation’s smoke shop—a necessary economic evil, perhaps, for a nation that has rejected casinos and gambling as sources of revenue. The stadium, on the other hand, is a symbol of unmistakable pride, part cultural center and part shrine to the Creator’s game (as they call lacrosse). Glass cases are lined with trophies, mementos, and photos dating back to the 1890s of Onondaga Athletic Club players grasping old-style wooden sticks and sporting striped jerseys with distinctive Os on their chests. Lacrosse moms were picking up their kids from practice, checking gear bags to be sure all the equipment they had come with was going home with them.

Freeman was sitting patiently at a table in the arena’s Fast Break Café working on his roster for upcoming games. He’s widely known as “Boss,” a nickname he got pegged with as a kid because he was big for his age and had a reputation for throwing his weight around. He’s still a big guy, with shoulder-length black hair and a hoop earring. As he smiled and said hello in a gentle voice that didn’t seem to match his frame, all I could think was how devastating his hip check must have been back in the day.

Onondaga lacrosse team, ca. 1902

He went to the counter, ordered a couple of sandwiches for us and then sat down. I told him again how sorry I was that his team had missed out on the World Championships. “How are your guys taking it now that they’re back?” I asked.

“I’ve been really impressed by how well they handled it all along, even some of the younger guys,” he answered without pause. “They worked hard for that chance. But you know what? We’re stronger as a team because of it.”

His proudest moment, he recalled, was when a CNN reporter asked for a show of hands of players who would be willing to travel on U.S. passports to England in order to make the game. “Not one hand was raised. No one even flinched or looked around. Why would we travel on another nation’s passport? Not just any nation, but the one we were planning to face in the finals?!”

After lunch and a quick tour of the stadium, we jumped in Freeman’s car and headed toward his house. A mile down the road we passed a kid walking along with a lacrosse stick in hand, practicing his cradling. “See that?” he laughed. “Everyone plays lacrosse here. When a boy’s born, he has a stick put in his crib. When he dies as an old man, his favorite stick gets buried with him. It’s the circle of life.”

“What if you don’t like lacrosse?” I asked, half kidding.

He looked at me as if there might be something seriously wrong with me. “Mostly you learn to like it. But hey, we got kids who play basketball and do pretty well. Baseball too. We invented that too you know.”

“Baseball?” I responded skeptically.

“Yeah, we call it longball but it’s pretty much the same game. Only we were playing it long before the whites came along.”

Farther down the road he spotted a guy on a building site scraping and cleaning up a 40-foot iron girder. He pulled up and the man leaned into the car. “Hey, Boss, what’s up?”

“That for the new place?” Freeman inquired. The two began to discuss the plans for the home he was helping his son build. Freeman offered some muscle and equipment to help haul free timbers that he’d heard were available. One of the downsides—or not, given the recent national epidemic of foreclosures—of being a sovereign nation is that banks won’t underwrite mortgages for homeowners, because if they don’t pay, the bank can’t come onto the nation to seize their property. As a result, people chip in to help each other build their own homes.

“You be sure to give those Braves a beating tonight!” the man called as we drove off.

The Braves were the Tonawanda Braves, a Seneca Indian team from near Buffalo that was coming down to play Onondaga in a three-game playoff series.

Freeman took me up to his home, a stately log cabin built on a couple of hundred acres of hillside forest. “No spikes, no nails,” he pointed out, proudly running his hands along the huge timbers. “The guys on my team and my own boys helped cut them down and drag them here.” He chuckled and cupped his hand over his mouth like he was sharing a secret, “I just told them it was part of preseason training!”

No one, Indian or white, has ever gotten rich from lacrosse. But when the sport first spread beyond the reservation, there was money to be made with traveling Indian shows. In 1878, a group of Mohawk and Onondaga Indians—faces streaked with war paint for full effect—arrived in New York City with a brass band in a four-horse wagon covered with advertisements for a lacrosse tournament to be held in what would later become Madison Square Garden. Custer had made his last stand just two years earlier, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was just getting going, and elites in eastern cities were enthralled with the romantic image of the “vanishing” Indian.

Accompanying the Indians was promoter and Montreal-born dentist William George Beers, the man often called “the father of modern lacrosse.” As a young member of the Montreal Lacrosse Club, which provided opportunities for middle-class residents to play games with nearby Mohawks, Beers became passionate about the game and determined to expand its popularity. At the age of 17, while working as a dental apprentice, Beers published the first pamphlet of rules, defining the length of sticks, field of play, size of goals, and so on. He was determined to bring “science” to the game and tame its more primitive elements. Though he admired the Indians’ athletic prowess, he argued that “the fact that they may beat the pale-face, is more a proof of their superior physical nature, than any evidence of their superior science.” Shorter fields, as historian Donald Fisher has put it, helped advance a game “in which ‘civilized’ team play and finesse replaced ‘savage’ mass play and brute force.”

Ironically, just as Beers and other early supporters brought lacrosse to the forefront and saved it from obscurity or worse, they also systematically excluded Indians from participating in the revival. Take this excerpt from Beers’s first full set of rules published in 1869, which were adopted widely as the holy scripture of organized lacrosse for years to come:

Sec. 5.—Either side may claim at least five minutes’ rest, and not more than ten, between games.

Sec. 6.—No Indian must play in a match for a white club, unless previously agreed upon.

Sec. 7—After each game, the players must change sides.

There, nestled innocuously between other how-tos, was one of many rules—some written, some just understood—that would be used to effectively bar Indians from competing internationally for decades. Indians were barred from play, at first, because they were better and stronger players than their white counterparts. When white teams played Indian teams the Indians would field fewer players to allow for an even match. Indian “ringers” would be hired and paid to play on amateur teams filled with middle-class whites, who regarded the game as recreation. This gave Indians from poor reservations a source of income but led them to be labeled “professionals” and therefore barred from all national and international amateur competitions.

A nationalist with a grand vision, Beers began to spread the gospel of lacrosse as the new national game of Canada. By invigorating Canadians with his newly conceived sport that “employs the greatest combination of physical and mental activity white men can sustain in recreation,” lacrosse could forge a unique national character and identity distinct from England and the United States. In Beers’s view, the noble “sons of the forest,” as he often referred to the Indians, would be remembered through lacrosse “long after their sun sinks in the west to rise no more.”

“We don’t give up easily,” said Freeman’s brother, Chief Shannon Booth. He had just returned from a meeting of the Grand Council, the traditional 50-seat governing body of the Iroquois League, which had been called to address the recent passport issues. “We felt the pain of 9/11. We understand and respect security needs as much as anyone,” complained Shannon. “But security doesn’t trump sovereignty.”

If I had even a vague stereotype in mind of what a modern Iroquois chief would look like, Shannon quickly shattered it. A boyish 35-year-old with a wispy mustache, faded trucker cap, T-shirt, and sneakers, Shannon is a chief of the Eel Clan, one of 14 chiefs representing the Onondaga in the Grand Council. Naively, I asked him how someone as young as he managed to get elected.

“No such thing as elections in our government,” he responded. “You can’t campaign your way into this job. The clan mothers watch all of us closely as kids, and when a chief dies and it’s time to appoint a new one, they get together and decide who has the right qualities. You’re chosen to play your part.”

The topic shifted back to lacrosse as we pulled up to “the box,” the outdoor rink that has been the heart of the game on the reservation for decades. A group of teens was applying a fresh coat of paint to the poke-checked and weather-beaten boards. “Be sure to paint the Visitors bench pink!” called out Shannon, laughing. On the other end of the patchy grass-and-dirt rink, three boys took turns practicing their 2-on-1 offense in the crease.

Box lacrosse is a faster, rougher, and, as most Iroquois will tell you, just plain better version of the game. Popular in Canada, and typically played on a cement surface in a defrosted hockey rink, “box” is a six-person game that lacks the verdant setting, loping grace, and exciting breakaways of field lacrosse but makes up for it with bullet-fast action, tight stick work, hot dog moves, and a 30-second-shot clock that keeps the pace frenetic. It’s been called the fastest game played on two feet, though its field-loving detractors call it a degraded, “hack-and-whack” version of the sport.

Box got its start in Canada during the Great Depression when the owners of the NHL hockey team the Montreal Canadiens were looking for a way to make money from their rinks during the off-season. While Iroquois teams continued to play field lacrosse right up to the 1950s, they consistently found themselves shut out from competitive play as the sport became the domain of middle-class “amateurs” in eastern prep schools and elite eastern universities. Exhibition games played between the Onondaga and college teams during this time were often marred by racism. As documented by Fisher, before one 1930 game between Onondaga and Syracuse University, local papers described the Indians as “a fighting band of Redskins” who were “out to scalp the Hillmen.”

So the Iroquois turned to box lacrosse. It was a more physical, high-contact game that appealed to their traditional style of play, with looser rules around checking and more opportunities for every player to run the whole field, shoot, and score. As field lacrosse got coopted and remade into the sport of choice for upwardly mobile Easterners, box was a game the Indians could make their own.

“Every Onondagan player gets his start here,” said Freeman, leaning against the splintered boards of the box.

Shannon agreed, reminiscing. “As soon as you’re old enough to hold a stick and get here on foot or bicycle, you show up for pickup games. If you’re the first, you start shooting around. Soon, another kid will be there to toss the ball with. Then, a third will arrive, and a fourth. In no time, you’ve got enough for a game.”

Freeman trained his four sons here. He took them up I-81 to the Carrier Dome, where they studied the field lacrosse game that their great-grandfathers had been excluded from.

“I’d teach them how to apply what they learned in the box to the field. I’d quiz them on plays as they happened. ‘Would you have made that pass?’ ‘What other options did he have?’ ”

Two of his boys went on to play for the Orange—Brett becoming captain and All-American—following in the footsteps of pioneering Onondagan Orangemen like Hall of Famer Oren Lyons Jr., Barry Powless, Travis Cook, and more recently, Marshall Abrams.

Now Freeman’s two young granddaughters have picked up sticks, a novel and even radical concept in Onondaga. Despite the explosion of popularity of women’s lacrosse elsewhere in the United States, Iroquois women are by tradition barred from playing the game. This may not always have been the case, however. There are accounts dating to the late 18th and early 19th centuries of women of several tribes playing the game, sometimes alongside or opposite men.

As Shannon explained the prohibition, “There’s medicine in the stick and the ball that’s not good for women. If your stick is lying in the middle of the living room, your mother or wife or sister can’t pick that stick up. That’s the way it’s always been with the Creator’s game.”

But Freeman’s granddaughters weren’t content to just watch and cheer from the sidelines, so they begged their father and grandfather to be allowed to join a girls’ league that had formed off the nation.

“Those girls worked on me real hard!” said Freeman. “So I went and asked two of our clan mothers for their permission, and they granted it.” He then proceeded to tell me how many goals they’ve scored this season, clearly proud that the Bucktooth touch had successfully jumped the gender divide.

Here in Onondaga, it’s not unusual for people to speak of lacrosse, even in casual conversation, as “the Creator’s game.” For all Indian tribes that have played it, lacrosse is, like everything on this Earth, a gift from the Creator and therefore bestowed with supernatural power, or “medicine.” One Ojibwe legend, as retold by Thomas Vennum, explains how the way of playing lacrosse first came in a dream to a boy adrift in a canoe:

In his dream, the boy saw a large open valley and a crowd of Indians approaching him. A younger member of the group invited him to join them at a feast. He entered a wigwam “where a medicine man was preparing medicine for a great game.” The lacrosse sticks were held over the smoking medicine to “doctor” them and ensure success in the game. After the players had formed into two teams and erected the goal-posts, the medicine man gave the signal to start, and the ball was tossed in the air amid much shouting and beating of drums. In his dream, the boy scored a goal. When he awakened, he related the details of his experiences to his elders, who interpreted it as a dictate from the Thunderbirds. This is how the game of lacrosse began.

Traditionally, the outcomes of games were believed to be controlled by spirits that could be manipulated only by powerful medicine men, or shamans, who were hired by teams to help ensure victory. One anthropologist who studied the Iroquois game in the late 19th century described how “shamans were hired by individual players to exert their supernatural powers in their own behalf and for their side.” Cherokee conjurers made the equivalent of voodoo dolls from the roots of a plant and used them to cast spells to make opponents sick. Mirrors were used by Choctaw medicine men during games to transfer the power of the sun to their players.

Balls were often made under the direction of the medicine man and imbued with magic in the process. Cherokee balls had to be made from the skin of a squirrel that hadn’t been shot. Parts of animals or birds would be secretly sewn into the ball to help it fly or roll fast or to otherwise invest it with magical properties. Among the Creek, Vennum relates, a team that had scored three goals could substitute a special “chief ball” that contained an inchworm and was believed to make the ball hard for the other team to see. Other objects placed inside balls included herbs, snake nests, fleas, and—much like the early tennis balls of the French—human hair.

Just down the road from the lacrosse box in Onondaga is a large open field where men still gather on occasion to play ceremonial games, which they refer to as medicine games. There’s no season schedule or roster for medicine games. They’re played only when they’re needed, for example, when there’s a serious illness or a social problem affecting the community.

“If I called a game now,” said Shannon, holding out his cell phone as though about to dial, “within a half hour I’d have thirty or forty men of all ages here with their sticks ready to play.”

The very first European accounts of lacrosse dating to the early 17th century describe remarkably similar ceremonial games being called by the medicine men. Father Brébeuf described such a game in 1637, referring to the game’s organizer as a “juggler”:

Sometimes, also, one of these Jugglers will say that the whole Country is sick, and he asks a game of crosse to heal it; no more needs to be said, it is published immediately everywhere; and all the Captains of each Village give orders that all the young men do their duty in this respect, otherwise some great misfortune would befall the whole Country.

Medicine games are still played the traditional way, with wooden sticks and a stuffed deerskin ball instead of a rubber one. Sides are chosen symbolically, often pitting married men again single men, or old against young. The number of goals to be reached is decided in advance. The emphasis is not on winning but, as Shannon put it, “playing the Creator’s game with a pure mind and heart.”

Alf Jacques handcrafts all the wooden sticks used in Onondaga medicine games in a small workshed down the hill from his mother’s house. The day I paid a visit he was also in the middle of washing all the Redhawks team jerseys in preparation for that night’s game.

How, I asked him, did the greatest living stick maker get stuck with such an onerous duty?

“Well, who else is gonna do it?” he shot back gruffly. “If I don’t do it, they show up to a game without their jerseys or they stink and look like hell.”

As the general manager of the Redhawks for the season, he was so busy with practices and road trips and laundry, he complained, that he was getting backed up on stick orders. He grabbed a beat-up notebook off his workbench to show me how he records the more than 200 orders a year he receives from all over the world. He has no website or email address.

“All word of mouth,” he said. “No one else in the world can make a stick like I do.”

Alf, 61, has a bushy mustache and wears his frizzy gray hair in a long ponytail down his back. He’s been making sticks in the same workshop since 1962. That year, he was 13 and a promising and tenacious young goalie who’d come up under the tutelage of his father, Louis Jacques, a Canadian Hall of Famer. As for so many on the reservation at the time, jobs and money were scarce, and when his stick broke the family couldn’t afford the $5 it cost to buy a new one. So, his father decided, they’d just make their own.

“We went in the woods, cut down a tree, and made the ugliest stick you ever saw. Then we made another that was a little less ugly.”

Alf Jacques crafting a lacrosse stick in his workshop.

Within six years the father and son had hired a team of workers and were producing 12,000 sticks a year. But they and the other Iroquois stick makers still couldn’t come close to matching the rising demand of a growing sport. In those years, even as the Lacrosse Hall of Fame was being enshrined at Johns Hopkins University and new programs were cropping up at colleges and prep schools up and down the East Coast, any player who needed a high-quality stick had to make the long road trip to the reservations of New York and neighboring Canada to buy one straight from the source. Efforts to mechanize the careful twisting and bending required to shape a stick failed repeatedly. The traditional technology of wooden sticks, which took up to a year each to produce, had become a major obstacle to the growth of the sport.

Even though it was forty years ago, Alf still sounds wounded when he talks about what happened next. In the early 1970s, after years of experimentation by entrepreneurs, the Brine Company in Boston and STX, a subsidiary of DuPont, began introducing plastic heads that were durable, flexible, and interchangeable with different sticks.

“Our production,” recalled Alf, “went from twelve thousand to twelve hundred almost overnight.”

Alf’s shed is one part museum and one part wood shop. On the wall behind his bench, in no apparent order, can be found a shiny new regulation stick ready to be shipped to Europe, a 19th-century replica of a Great Lakes stick with its signature small round pocket, and a prized stick he made for himself in 1978. Several metal sticks with purple and orange plastic heads propped in the corner look like children’s toys next to Alf’s originals, which are made from hickory.

The wood is split with a club and axe, carved into the right lengths, and then set aside to dry over a stove. He then steams the wood in a wood-fired oven to soften it for bending. Using a metal plate as a vise, he bends the head into the traditional crook form, ties it with wire, and leaves it for eight months until it’s dried and permanently bent. He then hand-carves and finishes the stick, using deer gut for the netting.

He pulled his own stick off the wall and handed it to me. The wood was worn and patinaed from 32 years of play. The handle is noticeably darker than the head, cured over years by the oils and sweat of countless games. Carved along its length are the Iroquois tree of peace, a turtle representing his clan, a fish (Fish being his nickname), and an image of male genitalia pierced by an arrow. “Dead nuts,” he said, referring to an old expression used in the building and machinery trades. “Means it’s perfect.”

I turned the stick in my hand, feeling the perfect balance of its weight, tracing the grain running lengthwise for strength. Alf grabbed it from my hand suddenly.

“You don’t want this stick!” he declared sarcastically, throwing it aside with practiced flare. “It’s old and worn out. You want the latest model, a 2010 titanium stick with an aerodynamic ultra-light molded head that comes in five different colors. Right?”

Once he’d gotten through his rant (which included the declaration that “there are a lot of things about plastic that truly bother me”) Alf acknowledged that nothing could stand in the way of progress and that if sticks were still made of wood there would be no forests left. For the game to take off and be accessible to millions of people all over the world, the technology needed to change and adapt. He knew that.

But, he added, something has been irretrievably lost in the process. He picked up the first stick he ever made with his father in 1966. “The spirit of the tree is alive in that stick, and the life of that tree came straight from the Creator.” He gripped the stick and began to dodge and roll around me as though advancing on an opponent. “When you’re playing, the life of that tree, that energy is transferred to you. That stick is talking to you, and if you listen you can learn.”

“With this”—he held up a titanium and plastic version—“you’re on your own.”

It was Friday night and the first semifinal game against the Braves was the big-ticket event of the weekend. The Redhawks were coming into the playoffs as the clear favorite, having lost just one regular season game. Families were piling into the metal bleachers, sporting team T-shirts and caps. Visitors from the Tonawanda Reservation had driven six hours for this event, and everyone would be making the journey to Tonawanda the next day for the second game of the series. For hundreds of years, games between villages or between nations have been major social events, providing a welcome excuse to visit old friends and renew ties. Thomas Vennum described such a game played in 1797 between the Seneca and the Mohawk: “On one side of the green the Senecas had collected in a sort of irregular encampment—men, women, and children—to the number of more than a thousand. On the other side the Mohawk were actively assembling in yet greater numbers.”

In earlier times, before the Onondaga decided to reject gambling and casinos altogether, a game like tonight’s would have involved widespread betting. Money, blankets, food, land, sometimes even human services were staked in collective bets intended to inspire players to give it their all. But even with thousands of dollars of bets on the line, winning has never been of much concern to Indian players and spectators. As the lacrosse great and spiritual Faithkeeper of the Onondaga, Oren Lyons Jr., once explained, winning and losing “didn’t seem to be so much a point of the game as the celebration, the sense of community, the being together with pride.”

A pregame announcement was made over the PA: “Women and girls attending tomorrow night’s game in Tonawanda are kindly asked to respect their nation’s ways by staying clear of and not touching the lacrosse box.”

Freeman spotted me and called me down to the box to watch his team warm up. Players were practicing power plays, setting up the pick-and-roll to free up the shooter. Eighty-mile-an-hour shots pounded off the enormously oversized pads of goalie Ross Bucktooth, a nephew of Freeman’s, who deflected every attack with one of Alf Jacques’s wooden goalie sticks. Freeman introduced me to assistant coach “Meat” Powless.

“How’d he get that name?” I made the mistake of asking.

Freeman leaned over, elbowing his friend and laughing, “Because he was blessed by the Creator!”

He walked me into the locker room and introduced his sons Brett, Drew, Grant, and the other players. Several, I noticed, wore Indian-themed tattoos and mohawks or long braids that trailed out of their helmets. After more than a century fighting stereotypes and caricature—especially in the world of sports, where tomahawk-wielding Indian mascots have been a sore point for years—these young Iroquois were comfortably reclaiming and reinventing symbols of their Indianness as if to say, “Still here, still warriors.”

The game was about to begin so I found my way to a safe seat behind the glass. The rubber ball was placed in the center rink for the face-off. In the 18th century, by contrast, games were often initiated by a young maiden throwing the deerskin ball down the field toward two facing lines of players. Jeremy Thompson, the Redhawks’ face-off master who had just finished his first season at Syracuse, won the battle and snapped the ball to a runner who quickly worked the ball into the crease, opening up a shot and scoring the game’s first goal.

The action was riveting and chaotic. The hard rubber ball ricocheted off the boards and glass, bouncing high off the cement. With no limit on substitutions, Alf worked one of the two doors to the Redhawks’ bench, opening and slamming it as players got sent on and off the rink. Penalties called for illegal checks or the occasional sucker punch or fistfight set up tense power plays.

The Braves hardly lived up to their name that night, giving up nine goals before scoring their first. Every play called by the announcer seemed to involve a Bucktooth: “It’s A. J. Bucktooth to Drew Bucktooth who takes a shot. Miss! Scooped up by Wade Bucktooth and fired hard. Goal!” They won 26–3, and in the days and weeks ahead would sweep the series and win the Can-Am League championship, earning them a trip to British Columbia to play against the best indoor Canadian teams in the Presidents’ Cup. They went all the way to claim the gold medal for Onondaga, a first in league history.

“They couldn’t handle us,” Alf boasted later. “We took care of everybody.”

Lacrosse, slow out of the gate, continues to pick up steam as one of the fastest-growing sports in the United States. According to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association’s annual participation study on team sports, it’s one of seven “niche” sports that saw increased participation in 2009 (up 6.2 percent). That’s all the more striking when you learn that basketball, baseball, soccer, and football all saw declines in participation in the same year. An early beneficiary of Title IX, women’s lacrosse has exploded, with the number of U.S. high school teams growing 127 percent between 2001 and 2009. The surprising departure at the end of the 2009 season of Princeton’s fabled winning coach, Bill Tierney, for the University of Denver—the edge of the known lacrosse universe—signaled that the era of eastern dominance and provincialism might finally be on the wane. And yet, even as the sport grows up and broadens its reach, it still can’t quite shake its reputation as an affluent white sport, more than ironic given its humble and diverse roots. In 2010, lacrosse in the United States had the highest percentage of participants (48 percent) from families with household incomes more than $100,000.

The recent swirl of international publicity surrounding the Lacrosse World Championships and the Iroquois passport issue served as a needed reminder, or first-time education, to many that this rising sport of lacrosse is an Indian creation, the ancient inheritance of a league of sovereign nations. Cody Jamieson and Sid Smith’s triumphant moment on the field in Foxborough had signaled for some commentators the arrival of a “new wave” of Native players who would define not just the past of the sport but its future.

Wondering about what that future might hold, I sought out Jeremy Thompson, as shining an example of that new wave as you can find. After a few challenging years, which included struggles with alcohol, he had just been named Most Valued Player of the Presidents’ Cup tournament and had finished his first season as All-America, second team, with the Orange. He and his three brothers—all rising lacrosse stars—had just graced the cover of Inside Lacrosse magazine armed with Alf Jacques originals and wearing moccasins and the bad-ass-don’t-fuck-with-me grimaces that lacrosse magazines love to feature. “The New Familiar Face of Lacrosse,” the headline reads.

When I mentioned it, Jeremy seemed somewhat embarrassed by all that attention focused on him. “Uh, no, haven’t read that yet.”

He also sounded conflicted about having achieved his dream of playing for the Orange. I asked him to compare the experience of playing in the box for the Redhawks with being on the field for Syracuse.

“On the nation, you know, I’m playing with my brothers. I know they’re most likely thinking the same thing I’m thinking. We’re there to play together, be with each other. Now at Syracuse, I don’t feel that way. I feel I’m in two different worlds.”

Until Jeremy was 12 or so he was in fact deep in another world, attending a Mohawk language immersion school on the Akwesasne reservation in upstate New York. The family’s decision to move back to Onondaga and enroll him and his brothers in public school was, he lamented, the worst thing for him at that time.

“I feel like I was just starting to learn where I came from, who I was, and then I got plunged into this other society. I’ve been trying to find my way ever since.”

Jeremy’s enthusiasm picked up while talking about an Iroquois cultural program he and a friend had just started in Onondaga for 12- to 14-year-olds. The kids learn about Iroquois language, crafts, and traditions, and elders and clan mothers come in to speak and share stories.

“Going through what I went through,” he said, “I just want to help make it easier and better for the young ones coming up now. If they learn who they are first and get grounded, then they can go out and handle American culture.”

When Jeremy’s lost his way in the past, he said, the medicine games have always brought him back to who he is and reminded him why he plays. “When we play our medicine games, you know, the ball is made out of the skin of the deer, stuffed with tobacco that grows from our Mother Earth. By playing, we’re giving thanks for the life in that ball and in the stick and all around.”