Nothing New Under the Sun

When it’s played the way it’s spozed to be played, basketball happens in the air, the pure air; flying, floating, elevated above the floor, levitating the way oppressed peoples of this earth imagine themselves in their dreams.

John Edgar Wideman

James Naismith had a deadline. Fourteen days to create a new sport that would sweep America within a decade, defy the limits of race and gender, provide a fast track out of poverty, generate $4 billion in annual U.S. revenue, and within a century be played by 200 million people worldwide.

Invent basketball. Two weeks. Go.

The expectations, of course, weren’t quite so ambitious when Luther Gulick, director of the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, tapped the 30-year-old Naismith to help with a challenging gym class he was leading. Soon after arriving at the school as a student in 1891, Naismith, a Canadian-born theologian turned phys-ed instructor, was recruited to deal with a class of 18 future YMCA administrators—“the incorrigibles,” as they’d been dubbed. The school had been established just a year earlier to train young men in the fundamentals of starting and operating YMCA centers across the United States and internationally.

Their course of study required just one hour of gym class every day. In the fall, that meant a mixture of indoor calisthenics and some outdoor football. In the spring there was baseball to keep things interesting. But through the long, gray months of the New England winter, the men, most of whom were pushing 30, were trapped in a dark gym, 65 by 45 feet, doing military marches and Swedish calisthenics and playing endless games of sailors’ tag.

Naismith felt their pain. “The trouble is not with the men but with the system we are using,” he told his professor. These men were used to playing team ball games and competitive sports and needed “something that would appeal to their play instincts.” What was needed was a game that would be “interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.”

Go for it, Gulick replied, in so many words. You’ve got until Christmas break.

Under the gun, Naismith, an accomplished athlete, spent the first 12 days experimenting with the sports he knew to meet Gulick’s vision for success:

. . . a competitive game, like football or lacrosse, but it must be a game that can be played indoors. It must be a game requiring skill and sportsmanship, providing exercise for the whole body and yet it must be one which can be played without extreme roughness or damage to players or equipment.

First, he tried a form of touch football, but these were men who lived for the scrum and loved to tackle. “To ask these men to handle their opponents gently was to make their favorite sport a laughing stock.” Next up was soccer, but windows were threatened, clubs and dumbbells were soon flying off the wall, and the game quickly degraded into a “practical lesson in first aid.” Indoor lacrosse proved even more dangerous, given the cramped quarters and lack of stick-handling skills. “Faces were scarred and hands were hacked,” and another game got tossed aside.

Naismith was dejected. With just two days left, he was preparing to admit defeat when he recalled a psychology seminar where Gulick had waxed on about his theory of invention, borrowing from a biblical passage from Ecclesiastes: “There is nothing new under the sun. All so-called new things are simply recombinations of the factors of things that are now in existence.”

So he began, methodically and obsessively, to break down the elements of popular games, examine them in isolation, and look for ways to recombine them.

His first brilliant decision? The game had to involve a ball. All competitive team games used a ball, so his must as well. But what kind of ball—small or large? Games with small balls, like baseball, cricket, and lacrosse, he noted, also required sticks, which made them harder to learn and more expensive to take up—characteristics that didn’t meet the needs of the YMCA. So he settled on a large ball, like the ones used in rugby or soccer.

Next, he considered why football, the most popular large-ball sport of the time, couldn’t be played indoors. Naturally, it was because you couldn’t have players’ faces repeatedly mashed into the gym floor. And tackling, he reasoned, was necessary in football because players were allowed to run with the ball and had to be stopped . . .

“I’ve got it!” he recalled later of the eureka moment when he stumbled upon the essential, unique premise of the game. The player in possession of the ball would not be allowed to run, but would have to pass or bat it to a teammate. Great, so far, but if that was the whole point of the game, he reasoned, it would be little more than a game of “keep away,” which he knew wouldn’t hold the interest of the incorrigibles. These men needed to be able to score goals, compete, and win.

Having neither time nor the patience of his subjects to waste on testing his ideas, Naismith played out experiments in his mind. “I mentally placed a goal like the one used in lacrosse at each end of the floor.” He quickly dismissed the idea, fearing that such goals would make the game too rough.

That’s when he remembered a quirky childhood game he played behind the blacksmith shop at Bennie’s Corners, Ontario, called Duck on the Rock. It involved putting a small rock, or “duck,” on top of a large boulder as the target, with each player standing 20 feet back behind a line launching their rock to dislodge the duck. The best way to do this and still retrieve your rock without getting tagged was to toss it in an arc.

“With this game in mind, I thought that if the goal were horizontal instead of vertical, the players would be compelled to throw the ball in an arc.” And if the goals were put up high enough, the defense couldn’t simply swarm around the goal but would have to secure possession earlier by stealing a pass.

It’s tempting to think that, as some have alluded, Naismith might have drawn some remote inspiration from ulama, where, following one set of rules, the Aztecs and Maya knocked the ball through an elevated stone ring to score. He could, plausibly, have read John Lloyd Stephens’s popular account 50 years earlier of discovering the ruined ball court in the ancient city of Chichén Itzá or seen artist Frederick Catherwood’s drawings of the crumbling stadium and its ornately carved rings. But there’s no evidence he ever did. And a good thing too, perhaps, or we might be sacrificing losing teams at half-court today!

Day 13 ended and Naismith went to bed dreaming of the game he was about to transfer from his head to the hardwood. “I believe that I am the first person who ever played basketball; and although I used the bed for a court, I certainly played a hard game that night.”

The next morning he went early to his office, grabbed a soccer ball, and began looking about for something to use as a goal. He sent the building superintendent, Mr. Stebbins, off to the basement to find some boxes, but Stebbins returned instead with the now-famous peach baskets, sparing us the fate of “boxball” and setting us down the path to the swish, one of sport’s most sublime sounds. He tacked the baskets to the balconies on either end of the gym—which just happened to be at that magical, dunkable height of 10 feet—posted a sheet with 13 rules to the bulletin board, and prepared to make history.

History was, at first, none too pretty. The 18 men scrambled and grabbed for the ball, fouls were committed, faces were scratched. “It was simply a case of no one knowing just what to do,” said Naismith. This was not yet, and wouldn’t be for decades, the aerial ballet of pivot plays, jump shots, and the crashing of boards. In fact, for the first four years or so there weren’t any boards to attack, not until the goaltending of fans sitting in the balcony became enough of a problem that backboards became standard equipment. When a basket was scored, a rare and heroic act at the time, the referee had to climb a ladder to retrieve the ball or would release it with the pull of a chain.

There was no limit to the number of players, with some teams fielding as many as 50 men spread out the length of the court. “The fewer players down to three,” wrote Naismith in his first description of the game in 1892, “the more scientific it may be made, but the more players the more fun, and the more exercise for quick judgment.” And there was no strategy or plays to set up other than passing continuously until a player was freed up close to the basket. When plays did begin to emerge, they were as often a creative workaround to poor gym conditions as the product of any strategic genius. The first players to “post up,” for example, did so around two steel posts fortuitously placed on the floor of an old YMCA gym in Trenton, New Jersey.

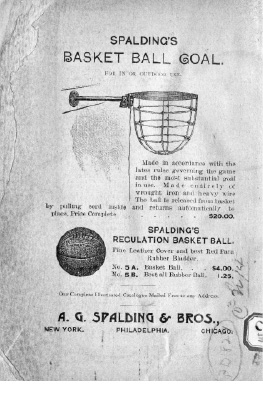

1894 Spalding advertisement for the company’s first regulation ball and innovative quick-release basket.

Though it’s hard to imagine basketball without the dribble, Naismith never envisioned that players would actually bounce the ball—nor would he have had any reason to. The balls of his time weren’t designed to bounce well or predictably. For the first two years, basketball had no specialized ball but was played with a soccer ball. Contrary to the Spalding Inc. website, which claims that “Naismith asked A. G. Spalding to develop the very first basketball,” the first game balls were actually produced down the road from Springfield in 1894 by the Overman Wheel Company, a bicycle manufacturer known for its popular Victor/Victoria “safety” bicycle. Their ball was slightly larger, heavier, and lumpier than a modern regulation ball, made from leather panels encasing a rubber bladder. Several times a game it would have to be unlaced in order to pump up the bladder. In 1919, Joe Schwarzer, a Syracuse All-American and early professional player, recalled the quirks and challenges of playing with those early balls:

The ball was four pieces of leather sewn together, with a slit in the center where they put the bladder in and laces over that. When you shot the ball, you could see it going up by leaps and bounds depending on how the air would hit the laces. And of course because it didn’t bounce as well as today’s ball, it was harder to dribble.

It was a lot harder to shoot. When you were shooting fouls, for example, you could almost tell when the ball went up what was going to happen by watching the laces. If it hits the rim on the laces, God knows what would happen. So when you shot, you wanted the ball to rotate just once, and you didn’t want the laces to hit the rim.

Neither Overman nor Naismith ever attempted to patent the basketball. Naismith never even patented the game he invented, writing later in life that “my pay has not been in dollars but in the satisfaction of giving something to the world that is a benefit to masses of people.” It’s remarkable, really, that it took 25 years for Spalding to step in to capitalize on Naismith’s magnanimity and Overman’s oversight. In 1929, George L. Pierce of Brooklyn, acting as “Assignor to A. G. Spalding & Bros,” was issued patent no. 1,718,305 for the “Basket Ball.” Five years earlier Pierce and Spalding had also patented an improved football.

Lumps and laces aside, players found creative ways to advance the first basketballs, rolling, bouncing, or even batting the ball over their heads to get it out of a corner. “It was not uncommon,” wrote Naismith of basketball’s lawless early days, “to see a player running down the floor, juggling the ball a few inches above his head.” Gulick, who was responsible for codifying the early YMCA rules, attempted to ban the dribble in 1898, arguing that “a man cannot dribble the ball down the floor even with one hand and then throw for goal. He must pass it. One man cannot make star plays in this style.” For the first three decades or so, dribbling (mostly double-dribbling, actually) was an inelegant defensive move that large players used to muscle their way toward the basket. I think that despite all the changes time has brought to the sport, most coaches today would still agree with Gulick’s essential philosophy: “the game must remain for what it was originally intended to be—a passing game.”

Early basketball action, ca. 1910.

That first game ended 1–0 on a 25-foot set shot by future YMCA executive secretary William R. Chase. Naismith’s invention was a hit with the incorrigibles, and, as he later wrote, “word soon got around that they were having fun in Naismith’s gym class.” Within weeks 200 spectators were lining the gallery for lunchtime games. At Christmas break, students took the popular game back to small towns across the country. Under the understated title “A New Game,” Naismith’s 13 rules were published in the January 1892 issue of The Triangle, a YMCA publication that went out to every U.S. branch. Within months, games were taking place at YMCAs from Brooklyn to Crawfordsville, Indiana, and in just a few years college ball was underway. From Springfield, the game spread with viral speed through the YMCA’s international network to Europe, South America, Japan, China, and the rest of the world.

I once spent three gloriously fruitless weeks on a boat in the Bahamas searching for the spot where Columbus first set foot in the New World. I had old maps, fragmentary accounts of the Genoese navigator’s first voyage, diligently dull reports from archaeological digs, and a healthy supply of sunscreen. Though it’s been the focus of countless expeditions, there’s not much knowledge to be gained from finding the spot. It doesn’t much matter which scrubby cay he and his crew first planted a cross upon, declaring it and all that lay beyond its shores property of the Spanish crown. What matters is everything that followed.

And yet there was, and always is, the romantic allure of finding the spot, that holy grail of discovery for any archaeologist or historian, whether they’ll admit to it or not. The spot on the African savannah where humans first walked upright. The spot in the Fertile Crescent where agriculture got its start. The spot between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers where blunt reed was first applied to clay tablet to carve the written word. The spot where the first baseball bat struck a ball and where the circuit of bases was first run.

For most historical events or evolutionary turning points, including that first line drive, there’s either no spot to uncover or way too many to count. But that’s never stopped us from searching, as baseball historians continue to do in their quest for the earliest, first appearance of baseball on American soil. Sometimes our pilgrim urge to stand on sacred ground is so compelling that we invent spots, like Plymouth Rock and Cooperstown, and persuade ourselves to believe.

That’s why I experienced a rare thrill, an archaeologist’s tingle of discovery, when I found myself standing on the cracked pavement at the corner of State and Sherman Streets in Springfield, Massachusetts, beneath the flickering golden arches of McDonald’s, inhaling the output of frialator vents that rattled in the cold December wind. I was standing on the spot. Never mind that the spot was on, as I’d been warned, “the wrong side of town,” a drug-ridden neighborhood where the liquor stores offer check-cashing services and where a recent drive-by shooting in broad daylight had left a 21-year-old man dead and a 13-year-old boy with a bullet in his leg. Even such tragedy couldn’t keep me away. This was, after all, the undisputed spot where Dr. James Naismith—the original Dr. J—tacked up his peach baskets to the balcony of a cramped YMCA gym long since torn down, divided 18 men into two teams, and gave the world “basket ball.”

Like most wannabe discoverers, I was of course merely retreading well-worn ground. Though largely forgotten and neglected like so much in Springfield, the site of basketball’s invention has long been known. In its heyday, this western Massachusetts city was one of the most important industrial centers in the nation. Straddling the banks of the Connecticut River at the nexus of major roads leading to New York, Boston, Montreal, and other major ports, Springfield was chosen by George Washington in 1777 as the site of the fledgling nation’s first armory. Here, Thomas Blanchard developed a lathe that could turn out interchangeable parts for the mass production of rifle stocks, an innovation that sparked the development of assembly line production. The armory turned out the first musket as well as the famous Springfield rifle, cranking out 200,000 a year to supply Union forces during the Civil War. “From floor to ceiling, like a huge organ, rise the burnished arms,” wrote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of the polished guns packed in racks. At its production peak during World War II, the armory employed 14,000 men and women to turn out M1 Garand rifles.

Aside from firearms and free throws, the “City of Firsts,” as it has been called, gave us the first American-English dictionary (Merriam-Webster), the first gasoline-powered car (Duryea Motor Wagon Co.), the first successful motorcycle (Indian), and The Cat in the Hat, by way of native son Theodore “Dr. Seuss” Geisel.

The city’s downward spiral began in 1968 with the Pentagon’s controversial decision to close the armory. As with so many other manufacturing centers, “white flight” to the suburbs drained the inner city of population and tax revenue as close to 50 percent of the industrial employment dried up. Urban blight spread and gang violence and crime peaked in the late 1990s and early part of the millennium. Beset with mismanagement and corruption, the city faced financial collapse and was taken over by a state-controlled finance board for five years to get it back on track. In 2008, even as it was showing signs of recovery, Springfield showed up on a Forbes list of America’s “Fastest Dying Cities” alongside depressed Rust Belt centers like Flint, Michigan, and Youngstown, Ohio.

In 2002, as part of a major redevelopment plan, the Basketball Hall of Fame opened a gleaming new $103 million, 80,000-square-foot facility on a strip of land wedged between I-91 and the Connecticut River. The Hall of Fame, which had its humble beginnings decades earlier on the campus of Springfield College, deserves credit for sticking with the city at its low point. Today hundreds of thousands of visitors a year from all over the world circle the Hall of Fame’s steel dome to pay homage to giants of the game and gawk at Michael Jordan’s oversized shoe collection. But most never see Springfield. They get whisked safely from offramp to onramp without ever needing to set foot, or drop a dollar, in the city of the game’s birth—and without ever seeing the spot where it all began.

Aaron Williams wanted to change that.

A lifelong resident and civic leader who lives near State and Sherman, Williams always knew the game was invented nearby, but like most people had never thought about where. When he learned that the first tip-off took place right down the street from his house in Mason Square, he formed a coalition of neighborhood groups and business leaders, enlisted the help of the Hall of Fame, and began raising money for a monument.

“People see [the Square] as one of the poorest communities in the state. I see it differently,” he told the local newspaper.

For Williams, the area’s storied past could help restore pride where pride was in short supply. He also thought a monument might attract visitors and spur some economic development. Williams knows all too well his neighborhood’s reputation for crime might keep some visitors away, but he exudes an unshakeable “build it and they will come” idealism that carried the project to completion.

“How do you calm fear?” he asked a reporter at the unveiling. “You show them history.”

That December day as I stood under the board announcing a special on “Sausaqe and Eqq McMuffin” (a thinly veiled plea for gs, no doubt), I thought how fitting it was for McDonald’s—which has over the years employed the likes of Michael Jordan, Larry Bird, LeBron James, and Dwight Howard to hawk the counterintuitive levitational powers of the Big Mac—to have planted their corporate flag in this hallowed spot and claimed it as their own. Naismith, who by the 1930s was already decrying the commercialization of his game, would be pivoting in his grave. The board outside the franchise should actually read, I thought to myself, “Basketball: Billions and Billions Served.”

But no flag had been planted. There were no photos, no plaque, not even a commemorative Happy Meal toy—nothing to acknowledge the spot and its importance. I asked a young man wiping down tables if he knew of any markers. He stared at me blankly and then called over his manager, who seemed annoyed at being pulled off the McNugget line.

“Nothing here,” he said. “But they just put up a statue of some people across the street.”

I dodged four lanes of traffic and trudged through a hard crust of blackened snow to find a modest bronze sculpture of a white man and a young black boy playing ball together—the manifestation of Williams’s vision. The man wears a turn-of-the-century uniform with the number 18 on his back. He’s bounce-passing (somewhat anachronistically, since they didn’t do that back then) the ball to the boy, who wears 91 on his back and Jordans on his feet. The game being played is not across space but across generations, cultures, and race—an assist from past to future. On the surrounding Plexiglas panels, a black-and-white photo of the first team, a cluster of tank tops and walrus mustaches, is exposed by passing headlights, then fades back into the dark.

When I spoke to Williams later about his role in making the monument a reality, he humbly played down his role. “Hey, I just didn’t want another kid to walk by that spot every day dribbling a ball and not know what happened here.”

When Naismith first set foot on that same spot in the fall of 1891, he was fresh from studying for the ministry at McGill University in Montreal. A devout Christian and talented athlete, he found himself as a young man torn between his desire to serve God and play ball. At McGill, he was a star football player, and while in Montreal he had picked up the Indian game of lacrosse, playing for the Montreal Shamrocks, one of the first professional teams. His friend and coach at Springfield College and the University of Chicago, Amos Alonzo Stagg, later told Naismith that he chose to play him at center because “you can do the meanest things in the most gentlemanly manner.” At the time, with controversy brewing over violence in football, playing that and other rough sports was viewed by some as inconsistent with a Christian way of life. Naismith’s teachers at the seminary disapproved of his double life on the gridiron and were none too pleased when he took to the pulpit one Sunday after a rough game against Ottawa with two black eyes.

But Naismith saw things differently. To him, the lessons learned in the heat of the scrum—lessons about self-control, sportsmanship, decency—were as important as anything he could deliver from a pulpit. He was, in this regard alone perhaps, of a mind with French existentialist Albert Camus, who wrote that he owed to the soccer of his youth “all that I know most surely about morality and obligation.” It became clear to the 30-year-old Naismith “that there were other ways of influencing young people than preaching.” He figured that “if the devil was making use of [athletics] to lead young men, it must have some natural attraction, and that it might be used to lead to a good end as well as to a bad one.” Forced to choose between the ministry and athletics, he found a way to merge the two at the YMCA.

The Young Men’s Christian Association got its start in London in 1844 with the first U.S. branches opening in Montreal and Boston in 1851 dedicated to “the improvement of the spiritual, mental, and social conditions of young men.” The Y movement emerged to deal with the seismic social and demographic changes that were sweeping western Europe and North America with industrialization. As men left farm and country, and often families, behind to take new factory jobs in the cities, the traditional social fabric began to unravel for many. At the same time, millions of immigrants poured into East Coast cities in search of new opportunities and new lives.

“These young guys were staying in rooming houses together, or homeless on the streets, with no families to look after them,” said Harry Rock, director of YMCA relations at Springfield College, whose campus office is in an 1894 redbrick Victorian gymnasium building. “They were getting into alcohol, prostitution, gambling, crime. So the Y formed to serve these wandering souls and keep them on the straight and narrow.”

With rented space, they opened reading rooms and meeting houses where men could come off the street to read hometown newspapers, join Bible classes, attend lectures, and get counseling.

“They quickly learned that Bible classes were a tough sell to these young guys,” said Rock. “Think about it. You don’t say ‘Come to the Y to build your Christian character.’ You say, ‘Come in and work out or play ball.’ ”

And so in 1869 the first YMCA gyms opened in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., with programs that dusted off Civil War military calisthenics. The whole idea of exercising indoors was still a new concept for most Americans, though the elite universities had begun building their own indoor facilities to train athletes in the winter months. Borrowing from exercise systems well established in Germany and Scandinavia, the new gyms were outfitted with dumbbells, pulleys, Indian clubs, parallel bars, running tracks, and other elaborate apparatus. Once incandescent lighting became broadly available in the 1880s the popularity of indoor recreation and sports began to find some traction.

After just a few years, there were nearly 400 YMCA gyms throughout North America. But with the expansion came serious management issues. Pay was poor and turnover high for the secretaries who ran the facilities as well as the physical education directors in charge of programs. Charged with “watching for the souls of men,” many secretaries failed to watch their budgets as well, leading to financial collapse for many branches. Clearly some training was needed. So Robert McBurney, the general secretary, turned to a colleague and Springfield minister, David Allen Reed, to set up a YMCA Training School. Reed, who was already training Christian lay workers, managed to lure the school to town with a building site ready for construction—at the corner of State and Sherman.

“To win men for the Master through the gym . . . to win the sympathy and love of men; to be an example to others.”

That was Naismith’s earnest response on his application to the YMCA Training School to the question, “What is the work of a YMCA physical director?” A holy roller with a theology degree who played college football and led phys-ed classes to help pay for college, Naismith was the ideal candidate for the new program. He took immediately to Professor Gulick, four years his junior but a man on a mission. Gulick was head of the physical education program and a leading advocate of “muscular Christianity,” a popular movement of the age embraced by Teddy Roosevelt and satirized by H. L. Mencken.

For centuries, the body, with its unholy needs and urges, was regarded as the source of all evil. Gulick and his muscular Christians, however, argued it was only the flabby body that was the source of all evil. Only the strong man who took care of all aspects of himself was fit to do God’s will. Writing of the merits of “vibratory exercise,” Gulick, a kind of evangelical Jack LaLanne, lamented the debilitating effects of the modern age on the manly form:

Many business men at forty are fat and flabby; their arms are weak, their hands are soft and pulpy, their abdomens are prominent and jelly-like. When they run a block for a train, they puff and blow like disordered gasoline autos. Men get into this condition because they sit still too much; because they eat more than they need, and because they drink.

He envisioned the complete man as one who balanced mind, body, and spirit. And he captured that vision in his creation of the iconic YMCA triangle—where spirit rests on top, mind on the left, and body on the right. “A wonderful combination of the dust of the earth and the breath of God” is how he described the logo that has survived six marketing redesigns over the past century or so.

The new game of basketball not only embodied perfectly YMCA principles, it was exactly the draw the young organization needed. From YMCA gyms, basketball quickly spread to church halls, Masonic temples, armories, public schools, city playgrounds, and other urban institutions. It began as and has remained an urban game, born of the spirit of social reform and designed to keep kids off the streets and out of trouble.

That’s been the mission of the Dunbar Community Center for the past century. The Dunbar is a legendary neighborhood gym that’s spitting distance from the spot on the outskirts of Mason Square. It began its life as a residential learning center for young black women going into domestic service in nearby mansions, and today serves as a safe haven for kids who might not have one otherwise.

“For two or three hours they’re not getting robbed, not getting shot. They’re playing ball, having fun,” yelled Mike Rucks, the gym’s 56-year-old athletic coordinator, over the afterschool din of squeals and sneakers.

It’s never been just fun and games at the Dunbar, though, Mike admitted. The gym has a hard-earned reputation as proving ground, or burial ground, for up-and-coming players in the region.

“They used to say around here that you hadn’t played till you’d played, and survived, Death Valley.”

Death Valley is the name for the Dunbar’s original gym, now closed and replaced by a shiny new facility that can accommodate the center’s ever-expanding youth programs. Mike led me down the hall, where he fumbled for keys and unlocked a dented door. He flipped the lights on in the gym, which had reverted to a storage area, revealing colorful murals and an old-school court hemmed in by tiled walls and a stage located just a few perilous steps behind the boards. The gym earned its name as much from the talented house players who repeatedly schooled visiting teams as it did from the court’s hard edges that drew plenty of contact in heated games.

“Man, we had some great throw-downs in here. Place would be packed, people lining the walls, talking trash: ‘You can’t play. Your mother can’t play.’ ” One of the visitors who ventured into the Valley and climbed out intact was a young man named Julius Erving, who came up in the late 1960s while he was a student at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

Lots of great, lesser-known players got their start here too, said Mike. Players with nicknames like “Gimp” and “Treetop.” Some who made it, like Travis Best, a talented guard from Central High who once scored 81 points, a state record, in a single game. He went on to play for Georgia Tech, the 1999–2000 Indiana Pacers team that lost in the NBA Championship to the LA Lakers, and various Euro teams. And then there were the ones whose hoop dreams were cut short. Mark Hall, three-time state champion who went on to play for Minnesota and was drafted to the Atlanta Hawks in 1982 but struggled with addiction and died from a cocaine overdose six years later. And Amos Hill, whom Mike and others describe as one of the most talented players to ever come through the Dunbar. “He never had some of the breaks growing up that kids have today, though,” Mike said, shaking his head.

“I blame some of the coaches as much as anyone. They’ll use a kid, tell ’em what they want to hear. I see it around here. Once the kids turn fourteen, that’s when the vultures start swooping in.” He’s become so disgusted by the coaches who prey on young talent that he’ll only coach up to age 13.

The stories of youth basketball’s dark underbelly and coaches and recruiters behaving badly are far too commonplace. In his devastating book Play Their Hearts Out, Sports Illustrated writer George Dohrmann went undercover to report up close on the corruption that’s rampant in a sport where players start being ranked at the age of 10. He tells the story of Demetrius Walker, now playing for New Mexico, who was described by Sports Illustrated in 2005 as “14 going on LeBron.” Walker’s Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) coach, Joe Keller, professed selfless concern for his charge’s well-being, arranging for him to be homeschooled by a tutor, caring for his well-being. “I’m not going to get a thing out of this,” Keller told Sports Illustrated in 2004. But as Dohrmann later exposes, Keller had arranged for homeschooling so Walker could repeat eighth grade and remain eligible for his AAU team. There was no tutor, and for an entire year the boy received no instruction at all. And it turns out Keller’s real aspiration was to get a cut of Walker’s contracts once he made it to the big leagues. “Within six years,” he later boasted to Dohrmann, “I am going to be a millionaire.”

Mike has seen as bad and worse in the 30 years he’s been hanging around the Dunbar. And he knows enough not to underestimate the make-or-break effect coaches and mentors like him can have on the lives of the kids who pass through his gym. He shares a philosophy, and coincidentally most of a name, with Holcombe Rucker, the renowned New York City Parks Department employee who in 1946 took responsibility for the playground cage at Harlem’s St. Nicholas Projects and turned it into his own private laboratory.

“Ruck,” as he was known by everyone, believed that basketball could be a one-way ticket out of the ghetto for talented black youth. And for the ones who never made it, it could be a way to learn life lessons that would help them succeed elsewhere. In the absence of city funding, he begged and borrowed balls, recruited volunteer refs, and set up a teen-targeted summer league and a legendary tournament. The Rucker, as the park was dubbed, wasn’t the place to refine your passing game. It was all about in-your-face street-ball theatrics and flash. As Nelson George paints the picture in his book Elevating the Game, players picked quarters off the rim after a layup and performed 360-degree dunks years before any Nike ad showed them how.

Surprise visits by the likes of Dr. J, Wilt Chamberlain, and Nate “Tiny” Archibald would set up one-on-one challenges where a local underdog could show his stuff and maybe, just maybe, get recruited to the pros. “This was on-the-job training when no jobs were available,” wrote Kareem Abdul-Jabbar of playing at the Rucker. “These were philosophers out there, every one-on-one a debate, each move a break through concept, every weekend a treatise. I took the seminar every chance I could.”

And for Ruck it was all about education. “Each one teach one” was his motto, and every chance he had he’d do just that, bending kids’ ears about staying in school and the value of education. Between games, he’d teach impromptu English lessons, look over kids’ homework, and choose players based on report card scores. It’s been said that through his efforts 700 kids received scholarships to help pay for college.

The coaches across Springfield at the small New Leadership Charter School have had outsized success with the same kind of education-first philosophy. The middle and high school with 500 students opened its doors in 1998 in the heart of one of Springfield’s most challenged neighborhoods. But unlike other public schools in the city, there are no metal detectors to pass through and no police presence—just vigilant teachers, parent volunteers, and kids who, for the most part, steer clear of the worst trouble.

At the Dunbar I’d been told, “Go over to New Leadership. They’ve got a story you need to hear.” Even though the school was only a mile and a half away and I had the right address, it took me forever to find it. After looping the block a couple of times, passing empty lots and the occasional boarded-up, derelict house, I spotted a young man standing on the steps of an old brick Catholic school waving to me. New Leadership, I learned, leases the building from the archdiocese and doesn’t have a sign of its own.

Joseph Wise, the studious-looking 29-year-old dean of students and girls basketball coach, greeted me on the stone steps, wearing a crisp white shirt and bright striped tie. He hurried me into the school’s tiled lobby.

“This is not an area you want to be lost in,” he cautioned.

Having grown up in New York City in the 1970s, I have pretty high standards for what I consider to be urban blight. I shrugged his comment off, thinking he was taking me for just another white kid from the suburbs. “It honestly doesn’t seem that bad.”

“Oh, don’t be fooled,” he laughed. “It’s plenty bad!”

The school, Joe told me as we walked down the hallway past trophy cases, is focused on “character development and college prep—in that order.” And they’re guided by a simple mantra that appears everywhere: “Success is the only choice.” So far, at least, it seems to be working. All 28 students in their first graduating class went on to college—a remarkable statistic in a city where only half of the students who start high school ever graduate.

Joe walked me down the hall to Coach Gee’s office, a storage closet behind the gym. Dusty trophies shared precious shelf space with toilet paper and cleaning supplies. Capus Gee, a broad-shouldered 52-year-old with a resounding laugh, doubles as boys basketball coach and head of maintenance. As we talked, balls repeatedly pounded the plywood board separating the office from the gym on the other side. Coach Gee recalled with visible pride the early days starting up New Leadership’s basketball program.

“Back then classes were happening in modulars and the only ‘gym’ we had was a cornered-off area of the cafeteria. Every practice I’d be calling around to churches all over the city, looking for a place to play. Half the time we’d be locked out, so we’d put the balls down and run laps outside instead. No surprise our kids could outrun the other teams every time.”

Things haven’t changed much since then. The school’s lease requires them to be out by 2:30, so they have to find other homes for afterschool activities. The girls team practices in a tiny grade school gym, with lunch tables pushed against the walls, and the boys JV team has use of a half-court at another gym.

About the time the program was getting off the ground, Springfield cut its budget for school sports by a third, leaving a gaping hole in a program that only charges players $10 to register and has to make up the difference.

“We didn’t ask for more help from the city. We just wrapped our arms around each other and did it ourselves,” said Coach Gee.

“Most of these kids are being raised by a single parent, or often a single grandparent. Some families can’t even come up with a $10 registration fee—or it’s either that or pay for the heat to be on. But everyone chipped in and cooked dinners to sell. Heck, I even cooked!”

The team raised $3,500 to close the budget gap that year and it showed the community what they could do when they all came together around a cause.

“Ever since, our end-of-the-year banquet has become famous. Other schools with big budgets are eating crackers and cheese. We have fried chicken, ribs, every kid gets a trophy and a nice hoodie. They leave feeling good about themselves.”

Coaches Gee and Wise live for basketball, trading stories of local heroes and high school stats. But for them it’s just part of a bigger, more important picture. Playing ball is just a way to build a kid’s character and confidence, teach them about discipline, teamwork, and other life lessons. And they know that for some kids, it’s the magic carrot that keeps them in school, off the streets, and out of trouble. As a policy, the coaches see progress reports for their players every two weeks and hold them accountable.

While every coach would pay lip service to the same philosophy, Coach Gee knows too many coaches who are more likely to put winning first. He shared the story of one of his most promising players—“kid was fast, great jump shot, you name it”—who was struggling in school and had to be held back. Another high school’s coach lured him with the promise that if he joined the school’s program he wouldn’t need to repeat his year. The student left New Leadership but ended up getting held back anyway, so he transferred to another school and got held back again. Now he’s 20 years old, taking freshman classes, and trying to figure out where the road leads from here.

I asked him if he knew of Amos Hill and what happened to him.

“Everyone who knows Springfield basketball knew Amos Hill. Most gifted athlete that ever came out of Springfield. But the same thing happened to him, only worse. Do you know he got all the way through high school and couldn’t read or write? No wonder the poor guy drank himself to death.”

“Our kids know school and home come first,” added Joe. “If you want to play for the team, you need to keep your grades up and do the right thing at home.”

In 2004, the first year of New Leadership’s boys basketball program, with no seniors to play and no gym to call their own, the varsity team won the western Massachusetts conference for their division and went on to be the first charter school to play in a state title game.

“That win was big for the boys team,” said Coach Gee. “But that was just the beginning. Then Qisi joined the girls team and put New Leadership girls basketball on the national map.”

“Qisi” is Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir, an honors graduate from New Leadership, now playing as a second-year point guard for the Division I Memphis Tigers. And if there’s anyone walking the streets of Springfield today who embodies the full legacy of James Naismith, Bilqis has got my vote.

In 2009, she finished her senior year at New Leadership with a staggering 3,070 career points, shattering the state record set 18 years earlier by University of Connecticut and WNBA star and TV commentator Rebecca Lobo. It was beyond unlikely that Bilqis could come out of a tiny unknown Division III charter school like New Leadership to surpass Lobo’s long-standing record by 300 points. It was astounding that she stood only five feet, three inches, 13 inches shorter than Lobo, when she set the record. But the most powerful part of her story, and the part she’s most proud of, is that she did it all while staying true to her beliefs as a devout Muslim woman. For four years, Bilqis drained jump shots, sunk buzzer beaters, and took the lane through a wall of much taller players with her arms and legs fully covered and a traditional hijab scarf wrapping her head.

I visited Bilqis at her Springfield home on an early summer day. Aidan came along, lured by the promise of a visit to the Hall of Fame. Bilqis was home from Memphis for a few weeks of family time before returning for training. She met us in the front yard of her yellow-sided house wearing a Gap sweatshirt and a black head scarf and greeted us with a shy smile and polite handshake. She’s soft-spoken and humble but exudes a kind of don’t-mess-with-me determination and confidence, all characteristics that seem to run in the family. Her father, a limo driver, was in the driveway washing his car. Her mother, who has run a day-care center out of the house for 30 years, was busy minding her grandchildren, who were chasing each other in circles. Both are converted Muslims who have raised their eight children within their adopted faith.

From as early as Bilqis can remember, she had a basketball in her hands and an uncanny ability to find the hole in any defense.

“We had a little-tike Nerf hoop in the living room,” she said, showing Aidan the spot where it was set up. “My brothers would play against me on their knees.”

“Really? How many brothers?” Aidan asked.

“At least two. I was always being double-teamed, but that’s how you learn, right?”

Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir playing for New Leadership, 2009.

From there it was driveway ball, AAU programs, and countless miles of road trips—but academics always came first. Her mother chose to homeschool her youngest rather than subject her to the Springfield public school system, where her older brothers had gotten “mixed up in stuff.” When eighth grade came around, her AAU coaches encouraged her to attend one of the large public schools with established basketball programs. But her mother was having none of it. So off she went to New Leadership, a school with no girls basketball program to speak of and no gym to call its own.

It helped that her brother Yusuf had found both academic and athletic success there, having helped lead his varsity team to the 2004 state championship. As Bilqis was entering her new school, her brother was heading to Division II Bentley College on a full scholarship.

“That girl defined scrappy,” recalled Joe of the four-foot, ten-inch, 80-pound girl who showed up that year to play on his new team. “Her jersey was hanging off her. But then she goes out in her first game and scores forty-three points, sixteen steals, ten assists. We were all like—whoa!”

In her freshman year, following Islamic law, she had to begin covering up. There was never a question of whether she would. She was devoted to her faith and to the sacrifice and discipline it required of her. That included playing on an empty stomach while fasting during Ramadan, pulling over on the side of the road or ducking into the nurse’s office to pray five times a day. But covering up was still a huge hurdle for a self-conscious teen to overcome, let alone a rising athlete like Bilqis.

She remembered the first day her mother dropped her off at practice in her new attire. “I was crying, I was so scared. I didn’t know what my friends were going to say.”

She also didn’t know about Under Armour.

“My mom and I were still figuring out what I should wear. I had these heavy cotton sweatpants, long cotton shirts, cotton head scarf. I was so hot and uncomfortable.”

Her coaches stood behind her commitment. They began researching light, breathable fabrics, looking for the perfect balance between high-tech comfort and hijab modesty. But there was still the social discomfort of being a symbol of Muslim identity in post-9/11 America. Enough referees questioned her attire that the team had to carry a letter of permission from the Massachusetts Athletic Association. Although she wasn’t the first Muslim woman to play at that level, the precedent wasn’t encouraging. The previous year, University of South Florida co-captain Andrea Armstrong was forced to quit the team when her conversion to Islam and adoption of the dress code led to a reprimand from her coach and hate mail from fans.

I asked Bilqis if she’d experienced similar incidents with spectators or rivals.

She shrugged the question off. “Most players and fans were totally respectful, but there were definitely some who said things.”

Her mother, who’d been sitting in the kitchen within earshot, chimed in.

“It was hard to watch sometimes. I remember once, she was taking the ball in from the sideline and behind her some idiot yelled ‘Terrorist!’ I hate to say it, but that kind of thing happens off the court too.”

Her father, who wears his gray beard long following Muslim custom, relayed a recent experience of his own from the day when the news broke of Osama bin Laden’s killing.

“I go into the store to get the paper and the owner holds up the headline and asks me if I’m going to cut my beard now. Then he says, ‘Only kidding.’ Can you believe that? Why would he think that’s funny?”

Bilqis never let the insults and trash talk get to her, though, and in four years never got a technical foul. Her standard line, coming back to the bench after an incident was, “It’s okay.” Then she’d go back in and unleash buckets of fury in response. By the end of her freshman year she had topped 1,000 points and by senior year she was averaging 40 points a game. The recruitment letters started arriving in the mail.

“They were double-teaming her when she didn’t have the ball, literally stuck to her like glue,” Joe said. “When she got the ball she’d have to drive through triple teams or more but she’d always find a way to the basket. I’d never seen anything like it. It was the Qisi show.”

Bilqis started her senior year with 2,300 points—just 400 points shy of Lobo’s record—and word began to spread.

“Scouts started calling, ESPN started calling, there was a fever building around her quest for the record,” said Joe.

But beyond the media swirl, the greatest effect was within the community. Bilqis became a household name and a symbol of pride, not just for Muslims, and not just for the black community, but for a city in need of a hero—a basketball hero, no less. By mid-January she was within 38 points of the record and playing at the Hoop Hall Classic tournament at Springfield College. Rebecca Lobo arrived with her family, wishing luck to her heir apparent as TV cameras rolled.

“I wasn’t really focused on the record,” said Bilqis. “I just wanted to win the game.”

New Leadership was down by 18 with 31 seconds left. She had 36 points when she fired an open three-pointer from 24 feet and it bounced out. She’d have to wait another game for her big moment.

The next game was supposed to be at the small elementary school gym that New Leadership borrowed for home games, but it needed to be moved to Commerce High to accommodate the crowd of more than 1,000. Bilqis was nervous that night, knowing recruiters, WNBA coaches, reporters, and the mayor of Springfield were all going to be in the stands. It took a long time for her to catch her rhythm and get on the board. Finally she got fouled and put up her 2,711th point, anticlimactically, on a free throw.

As she pursued the record and became a media sensation, Bilqis had to get comfortable with the idea of being more than just another talented ballplayer. She came to embrace her role as a symbol of hope and inspiration for people. She knew that every time she stepped out on the court she was opening minds and challenging stereotypes of Muslim women. And she played her part knowing that she was just building on a long legacy, that she owed a debt to a long list of pioneers who “cleared the lane” for her and made her achievement possible.

Senda Berenson, the “founding mother” of women’s basketball, arrived at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1892 at the age of 24 to be “director of physical culture.” A Lithuanian immigrant who had come to Boston with her family when she was seven, Berenson found herself cordially accepted but socially isolated as the only Jewish staff member on a Christian campus of 800. One former student’s description of her gives a hint of the kinds of bias she confronted. “She was smart and attractive, and not particularly Jewish . . . I mean some Jewish people are very different-looking from others and she was very attractive looking and perfectly dressed.”

Berenson was intelligent and focused, a woman with a mission: “Many of our young women are well enough in a way, yet never know the joy of mere living, are lazy, listless and lack vitality,” she wrote of the challenge she had come to take on. Like Naismith, she inherited her own group of incorrigibles and was challenged to find physical activities that were both fun and appropriate for a young Victorian woman to engage in. She came upon Naismith’s article in the Triangle newsletter about the new game that he’d invented in Springfield, just 20 miles south, and decided to give it a try with her class.

According to Naismith’s accounts, women were already playing at the YMCA Training School before Berenson staged the first organized game. A few teachers who had been coming by at lunchtime to watch the men play asked Naismith whether he saw any reason why women couldn’t play as well. “I told them that I saw no reason why they should not,” he replied. “I shall never forget the sight that they presented in their long trailing dresses with leg-of-mutton sleeves, and in several cases with the hint of a bustle. In spite of these handicaps, the girls took the ball and began to shoot at the basket.”

Naismith’s openness to having women play his game was progressive for the time. Women had, of course, been playing ball and chipping away at the glass ceiling of sports for centuries. As early as 1427, a young Flemish woman named Margot, dubbed the “Joan of Arc of Tennis,” became the sensation of Paris for humbling the city’s best male jeu de paume players while playing both backhand and forehand—without a racket. A century or so later Mary, Queen of Scots, an avid golfer, ran afoul of the church for hitting the links just a few days after her second husband’s passing. Women were joining the scrum in folk football games for as long as there are records of the games, though they were barred from formal Association play until the late 1890s. And Jane Austen in 1798 was among the first to write of the joys of baseball, with organized women’s teams following around 70 years later.

Despite this proud if erratic history, the idea that girls and women could withstand and even benefit from the rigors of athletic competition was still regarded as controversial. Members of the “fairer sex” were seen as physically and emotionally frail, their bodies designed by nature for childbearing and little more. Women were not allowed to vote or own property. And the prevailing attitudes of the day toward sexuality dictated that they be bound in tight corsets and wrapped in yards of fabric, making basic movement a chore. “Until recent years,” wrote Berenson, “the so-called ideal woman was a small waisted, small footed, small brained damsel, who prided herself on her delicate health, who thought fainting interesting, and hysterics fascinating.”

When Berenson started at Smith, however, attitudes were slowly beginning to shift. Women had begun to expand beyond their traditional roles as wives and mothers to fill new jobs in teaching, social work, and factories. Writing in 1903, Berenson captured the sea change that was under way and how it placed new demands on women:

Now that the woman’s sphere of influence is constantly widening, now that she is proving that her work in certain fields of labor is equal to men’s work and hence should have equal reward, now that all fields of labor and all professions are opening their doors to her, she needs more than ever the physical strength to meet these ever increasing demands. And not only does she need a strong physique, but physical and moral courage as well.

This new game of basketball, she determined, was exactly what her young Smith women needed to get them in shape for a new century. Designed to reward skill and agility rather than brute force, the game was deemed fitting for women in a way that football or even baseball was not. So on a gray March day in 1892, she posted a note on the outer door of the gym that read “Gentlemen are not allowed in the gymnasium during basket ball games.” An unexpected crowd filed into the gym with school colors and banners to watch the freshman and sophomore classes play the new game. Berenson hung wastepaper baskets on either side of the gym and divided the teams. Then, in tossing the ball in the air for the first tip-off, she struck the arm of the freshman captain and dislocated the girl’s shoulder. “We took the girl into the office and pulled the joint into place, another center took her place, and the game went on,” wrote Berenson.

Clearly, this was not going to be easy.

Senda Berenson tossing up the ball, Smith College, 1903.

But basketball seemed to instantly tap a deep vein of excitement and liberation in every woman who played, producing the same “feeling of freedom and self-reliance” that suffragist Susan B. Anthony credited to bicycling, another popular women’s activity of the time. Early teams captured this feeling in their names: The Atlantas, a San Francisco high school team named for the fleet-footed Greek goddess. The Amazons and Olympians at Elizabeth College in North Carolina. The Suffragists and Feminists, African American schoolteacher teams in Richmond, Virginia. Although Berenson’s version of the game—with rules modified to minimize physical contact—accommodated prurient notions of feminine decorum, it wasn’t long before women broke out beyond the genteel elite college scene.

The 1920s and 1930s marked an early high point for women’s suffrage and sport. Women won the right to vote, Amelia Earhart crossed the Atlantic by plane, and Mildred “Babe” Didrikson barnstormed her way into the American mainstream. Didrikson, who grew up in the gritty oil town of Beaumont, Texas, and went on to be a basketball star, pro golfer, and Olympic gold medalist, symbolized a new breed of woman athlete unfazed by middle-class stereotypes of femininity. When asked by a reporter if there was anything she didn’t play, she quipped, “Yeah, dolls.” Working-class women like Didrikson, used to the physical demands of laboring in factories or on farms, enjoyed the exercise, fun, and camaraderie that basketball offered and didn’t much care what the men thought of that.

Requiring just a ball and a makeshift hoop, the game spread rapidly through small rural towns, Indian reservations, and city projects. Social mores of every kind were repeatedly challenged and battle lines drawn. In Iowa, when the high school athletic association voted in 1925 to end women’s competition, one coach famously declared, “Gentlemen, if you attempt to do away with girls’ basketball in Iowa, you’ll be standing in the middle of the track when the train runs over!” That train made a lot of stops before it finally arrived in 1972 in the form of Title IX and, despite attempts to derail it, it’s stayed on track ever since.

Seven decades before Bilqis had to grit her teeth through anti-Muslim taunts, a team called the Philadelphia SPHAs endured similar slurs and threats on the court, but played on. The SPHAs, which stood for South Philadelphia Hebrew Association, got their start in the tough “cager” days when courts were ringed by wire or rope cages to prevent players from diving into spectators’ laps after loose balls. Until 1913, out-of-bound rules matched those of Walter Camp, awarding the ball to whichever team chased it down first. This was not by a long shot the no-contact sport Naismith had envisioned. Joe Schwarzer recalled returning home after his first cage game with rope burns across his back. Strategically positioned ladies were known to stab opposing players through the mesh with hatpins, and in coal regions of Pennsylvania fans would heat nails with miner’s lamps and throw them over the net at players.

And that was just the standard treatment. As a Jewish team that proudly stitched the Star of David and the Hebrew letters samekh, pe, he, aleph to their jerseys, the SPHAs had to deal with far worse. “Coffins and hangmen’s nooses would sometimes be painted on hometown floor to mark their spots, and in one hall the team was greeted with signs around the balconies saying, ‘Kill the Christ-Killers,’ ” recalled one player. The SPHAs began as a team of Jewish grade school kids that took on, and defeated, all comers in Philadelphia’s settlement houses. Like the kids from New Leadership, distant karmic heirs to their hardwood chutzpah, the SPHAs lacked a home court and were known as the Wandering Jews. They nevertheless wandered their way into seven American Basketball League titles between 1933 and 1945, at the same time their brethren in Europe were being shipped to concentration camps.

Before Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor, Wilt Chamberlain, and the era of black ascendancy, the cage was dominated by Jewish stars like Nat Holman, Eddie Gottlieb, and Harry Litwack who made up nearly half the players in the league.

Why were the Jews so good? Well, if you followed the logic of Paul Gallico, a top sportswriter of the time at the New York Daily News, it was because “the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind, flashy trickiness, artful dodging and general smart-aleckness.” Others, in the days before height was seen as a critical advantage, even suggested that the shorter Jews had “God-given better balance and speed.” When Jews faded from the game, handing the ball off to blacks in the 1950s, the same kind of pseudo-genetic theories were dusted off to explain the “natural” athletic ability of African American superstars.

To say that basketball was a Jewish game before it was an African American one would be to miss the point entirely. It was, and remains at heart, a city game. Whoever ruled the asphalt ruled the game. As Red Auerbach, the cigar-smoking son of Russian Jews who coached the Boston Celtics to nine NBA championships from 1956 to 1967, described growing up in the tenements of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in the 1920s: “Everywhere you looked, all you saw was concrete, so there was no football, no baseball, and hardly any track there. Basketball was our game.”

In March 1939 it was the New York Renaissance Big Five who ruled the asphalt and led the game as world champions. The Rens, called by John Wooden “the greatest team I ever saw,” were the first all-black professional basketball team. They got their name from the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom at 138th Street and Seventh Avenue, where a second-floor ballroom served as their home court. The team was formed in 1923 by Smilin’ Bob Douglas, a West Indian entrepreneur who grew up playing cricket and soccer but fell in love with basketball the first time he saw it played and decided to form his own team. Through the 1920s and 1930s the Rens were the toast of Harlem, playing for well-off tuxedo and ballgown-wearing blacks who came out to enjoy an evening game followed by dancing.

The Rens invited team after team to Harlem and one by one sent them home in defeat. Wrote the editor of a black newspaper, “It is a race between white teams to see which one can defeat the colored players on their home court, but so far, none of them have been successful.” That race was ended in 1925 by the Original Celtics, setting off one of the greatest early rivalries in basketball. Contrary to their name, the Celtics (no relation to the Boston Celtics) were an ethnic hodgepodge of Irish, Jewish, and German players who’d grown up together in the projects of Hell’s Kitchen. Over the next several years, the two teams traded wins in front of as many as 10,000 fans, and in the process found friendship and mutual respect.

When the American Basketball League was formed in 1926, it invited the SPHAs and other teams made up of urban ethnic minorities to join up. But the Rens and other black teams were rejected, and would be for another 20-plus years. In solidarity for their rivals and friends (and, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar argues, because there was more money to be made elsewhere), the Original Celtics refused to join the league. Through the 1930s, whenever the Celtics faced the Rens, Celtics center Joe Lapchick would hug Tarzan Cooper of the Rens in front of the crowd as a gesture against racism, eliciting boos and even death threats. “When we played against most white teams, we were colored,” said Bob Douglas years later. “Against the Celtics, we were men.”

Barred from organized league play, the team took their show on the road, barnstorming through small towns in the Midwest and South. During those Jim Crow days when blacks were forced to drink from separate water fountains and attend separate schools, signs outside many gyms might as well have read, “Black men can’t jump—here.” In some states, like Georgia and Alabama, interracial play was banned by state ordinance. In others, games featuring the Rens against all-white local teams got the most return at the gate. To pay the bills in those Depression years, they maintained a grueling schedule, traveling continuously between January and April and playing games every day, with two games on weekends. Douglas later estimated the team covered 38,000 miles a year at their traveling peak.

In small rural towns, the Rens often found themselves shut out of hotels and restaurants after traveling hundreds of miles. Gas station owners with rifles would refuse to fill their bus. Eyre “Bruiser” Saitch, a star of the team and pioneering black tennis champion, recalled how they “slept in jails because they wouldn’t put us up in hotels. . . . We sometimes had over a thousand damn dollars in our pockets and we couldn’t get a good goddamn meal.” Inside the small-town Masonic halls and school gyms where they played, things weren’t any easier. Referees routinely called more fouls against them than their white competitors. In one game against the Chicago Bruins, the Rens got called for 18 fouls while the Bruins had zero. When their manager protested an unfair call, a riot squad had to be called in to save the team from being killed.

Despite the odds, in 1932–1933 the embattled Rens posted a 120–8 record, with six of those losses to the Celtics. In one grueling 86-day stretch that year, they played and won a near-impossible 88 games. By 1939, they were a national phenomenon, so it was no surprise when they were tapped to be one of a dozen teams to compete in Chicago in the first World Professional Basketball Tournament. The organizers wanted to field the best teams in the country, black and white, league-affiliated and not. The winning team would get $1,000 and the world champion title. The Celtics lost in the first round, and the SPHAs were forced to withdraw due to injuries. In round one the Rens trounced a team called the New York Yankees and went on to face their neighborhood counterparts, the Harlem Globetrotters.

The two all-black barnstorming teams had followed very different paths to the championships. The Rens played the game hard and straight up, determined to win on their terms and show that blacks had the same abilities as whites. The Globetrotters, a team with equally talented players, were formed by promoter Abe Saperstein to entertain whites. Their version of basketball, full of clowning and trickery, was a form of black pantomime that played to white stereotypes and paid off handsomely at the box office. The Rens resented being overshadowed by the Trotters and their traveling minstrel show. Said Bob Douglas in 1979, “I would never have burlesqued basketball. I loved it too much for that.”

There was no burlesque or pantomime that day, however. Just two teams battling to become world champions and prove they had it in them. The Rens came out on top and in front of a mostly white crowd of 3,000 went on to defeat the white Oshkosh All-Stars to seize the title. Blacks everywhere celebrated the symbolic victory. After the game, Douglas held a banquet for his team and handed out championship jackets that read COLORED WORLD CHAMPIONS. John Isaacs, the team’s six-foot guard, asked to borrow a razor and carefully cut out the word “colored.” Douglas protested that he was ruining the jacket, but Isaacs just replied, “No, just making it better.”

In a sense, “making it better” has been basketball’s aspiration all along, part of the game’s founding DNA. Of all the major sports played in the world today, it’s the only one that was invented wholesale, and the only one designed to serve a social purpose. The father of basketball was no seer and no genius of the hardwood. He didn’t foresee the need for the dribble or the jump shot. He admitted only to having played the game twice and to have preferred wrestling for exercise and other sports for watching. He naively argued that basketball was a game to be played, not coached, and true to his belief remains to this day the only coach in University of Kansas history with a losing career record.

From his early experiences on the gridiron, however, he knew that whenever people face each other over a ball there’s always more at play than the game itself. The field or court is a stage where morality plays are regularly acted out, risks are taken, courage and character are put to the test. Naismith was an idealist and optimist who saw mostly the positive potential of his game to lift young people up, shape them—mind, body, and spirit—for the better. He fought for the right of women to play his game and at University of Kansas stood by his protégé and legendary black coach John McLendon against the school’s entrenched racist policies. “Sportsmanship,” he once told his daughter-in-law Rachel Naismith, “is shown as much in fighting for rights as in conceding rights.”

Looking back years later, McLendon reflected on Naismith as a mentor, providing what may be the best definition on record of what it means to be a good coach:

Naismith believed you can do as much toward helping people become better people, teaching them the lessons of life through athletics, than you can through preaching. So he had that in the back of his mind that a coach is supposed to make a difference between what a person is and what he ought to be. Use interest in athletics as sort of a captive audience type thing, you’ve got him, now you have to do something with him.

Bilqis has learned firsthand the give and take of the game, and how the hard-won victories and bitter losses always go hand in hand. Though it’s not been easy playing in hijab and dealing with name calling and ignorant questions, her spiritual journey has also given her a decisive advantage over other players in the stretch.

“Praying five times a day, fasting through Ramadan—it’s given me the structure and discipline to do whatever needs to be done,” she said.

It didn’t take long for Aidan to pick up on that inner toughness, and to admire her for it. Standing under the dome in the Hall of Fame after visiting Bilqis, taking in all the legends who have graced the game, Aidan asked, “Do you think Qisi will ever make it here?”

“Who knows,” I answered.

“I hope she does,” he added.

After setting the Massachusetts record, Bilqis was inundated with recruitment letters and offers by NCAA finalists like Boston College and the University of Louisville. They rolled out the red carpet on campus visits and offered all the usual perks. But she chose instead to go to the University of Memphis, a lower-ranked upstart. I asked her why she’d made such an unlikely choice.

“They were interested in me and my religion. They showed me the campus mosque. Some of the big-time schools don’t care about academics or your personal life, just basketball. That isn’t for me.”

Bilqis arrived at Memphis to great fanfare only to sit out her freshman year with a torn ligament in her knee. That gave her plenty of free time to answer the Facebook messages that streamed in from Muslim girls as far away as Indonesia who have been inspired by her story. In her second season, with a senior guard ahead of her she didn’t get much floor time and found herself losing some confidence in her shot. When I spoke with her, she wasn’t so sure whether she had a bright basketball future ahead or not.

“I’d still like to play in Europe, but my WNBA dreams have kind of fizzled out. That’s okay ’cause I was never dependent on basketball. I’ve got a lot of other stuff I want to do with my life.”

“Be a special guest of the president at the White House” was never on that life list, but in July 2010 she added it and checked it off all at once.

“My dad told me there was a letter for me with gold lettering and the presidential seal,” she recalled of the day when the invitation arrived. “I seriously thought he was just messing with me.”

It was an invitation from the White House to celebrate iftar, the feast breaking the Muslim Ramadan fast, with President Obama and 70 other honored guests. When Bilqis arrived wearing a purple head scarf, she was given a tour of various rooms and was then told to find her seat.

“I saw my name card and looked at the setting next to me, which said ‘President Obama.’ Next thing I know I’m sitting knee to knee with the president of the United States talking about maybe playing one-on-one someday. I was like pinching myself!”

In his recorded remarks, President Obama singled out Bilqis, calling her “an inspiration not simply to Muslim girls; she’s an inspiration to all of us.” He then teased her about her height.

“She’s not even five feet, five inches. Where is she?” he asked, looking across the room.

Bilqis didn’t miss a beat. “Right here,” she answered, standing tall.