CHAPTER 1

A Layman’s Topography, Brief

History and Political Guide

I have looked long on this land

Trying to understand

My place in it

R. S. Thomas

THE MOOR WHERE THE River Dart rises has always been a special place, a high place. Bronze Age settlers divided it meticulously between them; Britons circled it with hill forts; Anglo-Saxons peopled all its valleys, though the Dark Ages were as dark here as anywhere. King John retained its heart as royal Forest or hunting ground in 1204; his son Henry (III), gave it away as a ‘chase’ but Edward I got it back and invented the Duchy of Cornwall to hold it in 1337. It still does. All Devonians, bar those in Totnes and Barnstaple, had rights of common grazing on it for at least 1,000 years. Its minerals and stone have been exploited for longer than that; and for 5,000 years someone somewhere has been tinkering with its soil and vegetation, moving its boulders into walls, splitting some for gateposts, manipulating its water or, having to cross it regularly, has marked the way (Fig. 1).

It is now, has been for more than 50 years, a National Park. That modern special status recognises all those historic processes that have contributed to it and its landscape through time. The national park purpose points up the need to keep some of these processes going, to care for the evidence of the others and of course to conserve the contemporary natural Dartmoor that veils but does not obscure them. It also demands that enjoyment and understanding of all its special qualities are facilitated and promoted.

FIG 1. Sennett’s Cross, in the col where the B3212 crosses the Two Moors Way. Crosses marked routes, and often boundaries too.

THE NATURAL SHAPE OF THINGS

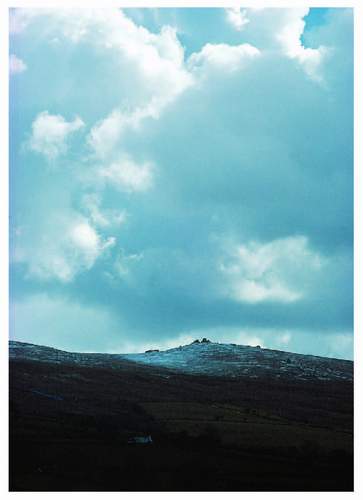

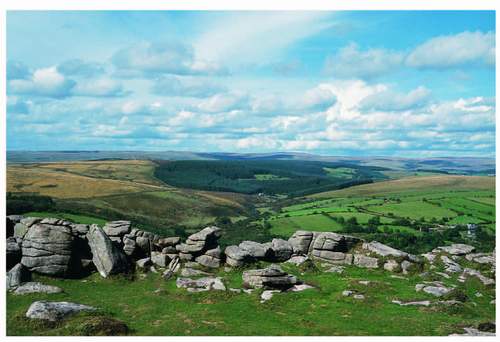

‘The Moor’, as everyone in South Devon refers to it, is a compact upland lying between the rivers Tamar and Exe or, if you prefer it, between the A30 and the A38 just after they have diverged at the end of the M5. The National Park boundary contains 953 square km (368 square miles). It is just over 38.6 km from Sticlepath in the north to Bittaford under Western Beacon at the southern extremity, and 37.8 km from westward Brentor to the River Teign below east-facing Hennock. Its highest hill – High Willhays – reaches 621 m above sea level or Ordnance Datum (OD) and the River Dart leaves the Park at it lowest point just below Buckfast, 30 m OD. The great bulk of Dartmoor is a granite mass with a narrow border palisade of hard, baked and twisted country rock, its aureole (see Fig. 16), and the whole now stands well proud of the rest of the South Devon landscape (Fig. 2). That landscape is effectively a set of descending level surfaces dissected by radiating narrow valleys and fashioned from the older rocks that once wholly contained the granite.

The molten granite – rather like a blister on an extensive deep-seated igneous body stretching from Dartmoor westwards beneath the southwest peninsula and beyond – was intruded into these folded and finely divided rocks some 280 million years ago (Ma). Between then and now the granite has been exposed to the air and buried and exhumed again at least once. Then, just after the Devon landscape that

FIG 2. Dartmoor rising above the South Hams landscape, the profile from Western Beacon through Ryder’s Hill on to Holne Moor.

we know had been blocked out and the main river pattern set (perhaps only 3 million years ago), the whole of Dartmoor was isolated as an island by a short-lived marine invasion reaching up to what we now measure at about 210 m OD and thus creating, however briefly, a ‘Dartmoor’ island. It was pauses in the sea’s retreat from that island’s shores that produced the wave-cut surfaces that provide those step-like summit ‘flats’ of the South Hams. Not long after that retreat began – perhaps it had reached halfway, the present 120 m OD mark, and only 1.6 million years ago in time – the northern hemisphere’s ‘Great Ice Age’ intervened. It lasted more than 1.5 million years and involved some 50 or more glacial advances southwards with related interglacials, many of which were sub-tropical.

Throughout the glaciations Dartmoor always sat just south of the extended polar ice cap and its surface was never subject to moving ice, but sculpted and moulded by all those forces evident in the sub-arctic zone today. The North West Territories of Canada, Alaska, Novaya Zemlya or, nearer at hand, Spitsbergen will demonstrate to the visitor now what was going on in Dartmoor as recently as 15,000 years ago (BP or ‘before the present’). Compare 15,000 with 280 million and you will perceive the span of the Dartmoor’s earthen landscape history. The ‘grand old Moor’ of Robert Burnard, joint founder of the Dartmoor Preservation Association, owes its singularity and its gross anatomy to the beginning of that span and the detail of the physical features that we see, to the end of it. The contemporary living clothing of the whole, in all its great variety of plants, began on a ‘clean’ surface only 14,000 BP. But, while we humans have lived here longer than that, we have actually only worked with and around the surface rocks, that vegetation and its dependent animals for just a little more than half that time.

In all the postglacial period Dartmoor stands up from the rest of the South Devon landscape whose roughly east-west geological grain is interrupted only by the parents of our contemporary rivers carving their way across it to either of the Devon coasts and thus to the Western Approaches. Throughout, Dartmoor’s altitude has secured a far greater annual rainfall than any other part of Devon, and thus most of those rivers have had their birth in one of its two plateaux as Figure 38 shows.

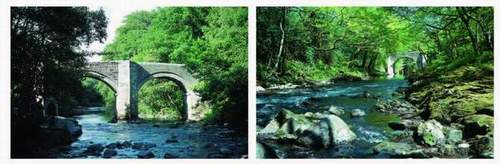

All of the River Dart’s headstreams, but one, flow out of the substantial northern plateau. The exception is the Swincombe, which feeds and then issues from Foxtor Mire just south of Princetown and joins the West Dart downstream of Sherberton. The West Dart has by then already collected the Blackbrook, the Cowsic and the Cherry Brook. The East Dart is joined by the Walla Brook (one of three with the same name within the Park) before Dartmeet and then the so-called Double Dart is strengthened by the West and East Webburns which come together about a mile before they join it on its left bank a third of the way round the great Holne Chase meander between New Bridge and Holne Bridge (Fig. 3). The Double Dart picks up some short minor streams from the northern flank of the southern plateau, the O Brook and Venford Brook among them, and then it collects the longer and eastward flowing Holy Brook at Buckfast, the Mardle at Buckfastleigh where it also collects the Ashburn (or Yeo) from the north. Much nearer the sea, within its tidal reach and well out of the National Park, it is joined by the Harbourne which rises on the southeastern edge of that same plateau. The whole upper catchment of this extensive river system occupies some 25 per cent of the National Park, and the nomenclature suggests that early historic settlers

FIG 3. Medieval New Bridge (above left) and Holne Bridge (above right) which mark the limits of the Double Dart gorge’s deeply incised meander round Holne Chase.

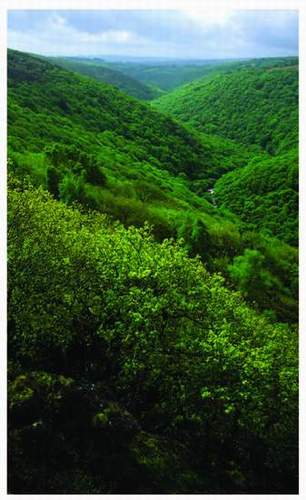

approached the moor up the main arterial valley whose river may have been named already. Physical features on the whole have older names than settlements and other artefacts, so even the Anglo-Saxon pioneers who arrived in South Devon by sea ahead of the military invasion of Wessex may have inherited ‘Dart’, whose root is a British word meaning oak. The sides of the Dart valley from Totnes to Dartmouth are clothed in oakwoods now, as are those of the Double Dart within the Moor (Fig. 4).

FIG 4. The Double Dart’s wooded gorge from Bench Tor. (C. Tyler)

The land not in the Dart catchment in the northern plateau is drained in a radiating clockwise order from the southwest corner by the Walkham which joins the Tavy, the Lyd, West and East Okements, Taw and the Teign. This last is joined by the Blackaton Brook; the Bovey, which has already collected the Wray; the Sig and the Lemon, which rise and join within the Park, but are confluent with the Teign at Newton Abbot. Like the Dart the Teign has two main headstreams: the North and the South Teign, whose confluence is upstream of Chagford. From 4 km above that small town the river flows generally eastward and below it enters a deep gorge, seen in Figure 57, some 12 km long across the northeast of the national park and then turns south forming its eastern boundary for another eight, collecting many small right-bank tributaries on the way. The southern plateau in its turn is largely drained (from west to east) by the Meavy which joins the Plym, and the Yealm, Erme and Avon which traverse the South Hams fairly directly to lengthy estuaries flooded twice daily by the waters of the English Channel.

FIG 5. Dartmoor’s northern edge from north of Cosdon, the dome on the left, and stretching to the Yes Tor-High Willhays ridge on the far right.

The summits of the landscape surrounding Dartmoor oscillate around 150 m OD, sometimes reaching 200 m closer in, but even at its lowest end the Moor’s southern extremity, Western Beacon, is 334 m OD which is gained in less than 400 m, as the crow flies, from the slate country below. On the northern flank Cosdon (Cawsand Beacon to some) and Yes Tor rise spectacularly steeply from the in-country in 1.5 and 3 km respectively (Fig. 5). On all but the northeastern boundary, then, where the National Park would run into the Haldon Hills were it not for the Teign valley, Dartmoor rises abruptly out of its landscape setting.

Approached from the northern arc of the compass – eastwards or westwards on the A30, or across country from Bideford, South Molton or Tiverton, northern Dartmoor is a blue-grey escarpment above the green foreground. As Figure 2 showed, the same colour contrast occurs in the south, though perhaps the foreground is often more chequered here than in the north – more bare red soil in winter, more barley, maize and oil seed rape later on. Travelling northward on some lanes and on some days through the South Hams, Western Beacon presents a narrow blue dome – for all the world like the bow of a large submarine on the surface cleaving through a greenish sea.

The maritime analogy can be more helpful than you might think, particularly in north–south section. If Western Beacon is the prow then Yes Tor to Cosdon is the transom of a taller poop. Recall the long axis of Henry VIII’s Mary Rose, and even the waist between has its reference in the central basin of the upper Dart separating the northern plateau from the southern as after-castle and forecastle, of different size and height. For that is the north–south profile of the Dartmoor mass. Highest at the extreme northern edge and its summits all the way to the southernmost hill steadily lessening on a remarkably steady gradient of 7.6 m to the kilometre when it was first perceived. That slope is broken only by the width of the central basin, perhaps 6.5 km from Beardown to Ter Hill, 9 km from Hameldown Beacon to Holne Ridge. The basin, of course, has a western rim linking the two plateaux through the Hessary Tors near Princetown and Nun’s Cross – as though the Tudor ship was listing heavily to port.

You can actually see the north–south slope – from the right viewpoint at the right distance away. Looking westwards from Lawrence Tower on the northern tip of Great Haldon just west of Exeter, or eastward from Caradon Hill on Bodmin’s edge, the southerly slope of the Dartmoor’s summit profile is clear. Indeed from Caradon Hill the western rim of the central basin makes that slope seem continuous.

But Dartmoor as a discrete upland appears on the skyline from much further away. It springs into view just before the A35 drops off the East Devon plateau to Honiton. From Exmoor the whole northern escarpment looms above the wide vale of the Culm and red-Devon country in between. From Start Point (that south-southeastern extremity of South Devon) across the corrugated South Hams the other Dartmoor scarp from Lee Moor to Hay Tor is a splendid 27-km two-dimensional backdrop. From a boat at the Eddystone it dominates the landfall, indeed it is visible from anywhere on the arc from Portland Bill to the Dodman on a clear day. On a very good day you can see it from as far away as the Lizard. It is after all the highest, widest – biggest in all senses – of the granite hills and, counting Exmoor in, of all the southwestern piles.

THE CURTAIN WALL

From any distance it is the mass that is impressive – closer to, specific features mean more. Distinctive silhouettes like the dome of Cosdon are easily memorised, and in an anti-clockwise direction, so are the Yes Tor-High Willhays ridge, the jagged profile of Sourton Tors and Great Links Tor’s double peak (Fig. 6). Down the west side the chain of Arms Tor, Brat Tor, Hare Tor and Ger Tor mark the outer edge of the plateau and then Blackdown leads the eye out to

Brentor with its summit church (Fig. 7). The heap of Cox Tor almost hides Great Staple’s twin columns seen in Figure 52. Pew Tor and Vixen Tor are a 100 m lower but still unmistakable. Sharpitor and Sheepstor, shaped as named (Fig. 8), regain height but then there’s a gap where china clay waste tips take the eye until the southern extremity that Western Beacon declares. Ugborough Beacon and Brent Hill (Fig. 9) in the aureole are close up the southeast edge, then there’s a glimpse of Rippon Tor just before the double asymmetry of Hay Tor looms. All are major landmarks from ‘off’ the Moor.

Unmistakable Hay Tor is visible from an arc that runs from beyond Moretonhampstead in the northeast round to well west of Salcombe in the South Hams. It was almost certainly a terrestrial navigational marker for prehistoric metal traders and eventually Anglo-Saxon settlers, even if their undulating

FIGS 7 & 8. (above left) Brentor, the western extremity, with its crowning church seen from the south across Whitchurch Down; (above right) Sheepstor crouching above Burrator.

progress on the watershed route-ways from the coast through the in-country demanded other intervening ‘signposts’. The ‘Hay’ was ‘Hey’ or ‘high’ before the nineteenth-century map makers wrote down what they thought they heard locals say- simply because of its universal and singular visibility as the observer straightened his back and looked upward from his plodding journey or his cultivating toil (Fig. 10).

FIGS 9 & 10. (above left) Brent Hill. a southeastern dolerite tor on the Devonian/Carboniferous boundary; (above right) The well-known double peak of Hay Tor looming over the middle east, looking south from Langstone Cross.

FIG 11. Inside the plateaux: (top) from above Dinger Tor towards Cranmere Pool and (above) from above Plym Head eastward to Ryder’s Hill.

The origin of those tors, rocky piles with necklaces of boulders called clitter, will be examined not so long hence. For a huge number of visitors – from ‘up country’ (beyond Exeter), from other countries in increasing numbers and from Devon’s own in-country – tors define Dartmoor. They are crowded at its edges and thus easily seen from the approaches, they crown many hills and they are never far from roads in popular eastern Dartmoor. They loom over riverside footpaths. They are remarked because they are very rare in visitors’ home landscapes. Surprisingly, although odd ones exist there, they are equally uncommon in both soft-rock metropolitan England and in the harsher, harder ‘Highland Britain’ beyond the Bristol Channel, where moving ice smoothed so much and melting ice dumped ‘drift’ on so much more.

They are rare too, at home as it were, in the interior of the two Dartmoor plateaux. Away from the ‘edges’, whether of the whole Moor, of the central basin or of some narrower, deeper valleys the Dartmoor surface and thus its skyline, seen from within a plateau, is smooth as Figure 11 shows. Long low interfluves separate wider shallower troughs, sometimes long themselves – sometimes short depressions. In both, peat accumulates because water from surrounding slopes gathers there, oxygen is excluded and plant remains cannot rot completely. This water is surplus to the below-ground capacity, but the rainfall has been so high for most of the vegetated last 9,000 years that there has been a prehistoric and historic inhibition on rotting even on the wider ridge crests and the low summits from which many of them radiate. The result there is blanket peat – a wonderfully appropriate name – commonly half-a-metre thick on the southern plateau, but 2 m over the northern and reaching 4 to 5 m around the heads of the East Dart and the Taw and at Cranmere Pool (Fig. 11 – top). In the moorland valley bottoms and in even more ‘civilised’ hollows, ‘mires’ and ‘raised bogs’ occur: they are the specialist labels for the other peat-based features which are not necessarily confined to the uplands. Mires in Dartmoor have near-horizontal peat surfaces riddled with pools and small water channels as in Foxtor Mire south of Princetown or Muddilake east of it, Taw Marsh in the north, in Halsanger Common in the east and along the Walla Brook and West Webburn among the fields. In raised bogs – a small one lies in the valley west of Crockern Tor, a larger one above Statts Bridge, both close to the B3212 – the peat swells upwards in the centre creating a low cambered surface, making for easier cutting for early fuel seekers. Both of these bogs can vary considerably in area and the smallest patches of peat, which occur in isolation and often perched on valley sides where springs break out, are known as ‘eyes’ to commoners and their stockmen, whose sheep and cattle may blunder into them in poor visibility.

Blundering is not confined to lame or sickly stock. Peat surfaces in all their forms do affect people’s progress on foot and on horseback and the traveller needs to be able to see the route ahead. A nineteenth-century huntsman called Philpotts caused ‘passes’ to be cut through the peat on some of the regular routes his pack took, one is in Figure 12, and some are shown on the modern 1:25,000 map. Given that the plateaux at almost any time can protrude into the cloud base, visibility can change with disturbing rapidity. This combination bedevils Dartmoor myth

FIG 12. Peat pass in the upper east Dart valley – an upright stone marks each end of the cutting. (DNPA)

and legend but it is as well to take it seriously and adequate precautions in any case before and during an excursion into the moorland heart. Whatever else, make sure someone knows where you intend to go and how long you intend to take.

Immediately around the two peat blankets on the plateau tops the surface still bears peaty damp soils in a great, slightly fragmented, figure-of-eight zone enveloping them both (Fig. 94). They carry coarse grasses and heather and extend off the open moorland commons into elderly and extensive enclosures – the ‘newtakes’, ‘taken’ from the commons or the Forest over at least the 700 years into the late nineteenth century. There are many ‘islands’ of these poor soils separated from that main zone, most are small but the largest, east of Widecombe, is big enough to hold that same, roughly concentric, pattern of common and enclosure even at its smaller scale. The newtakes still largely bear moorland vegetation. However, because they are in single occupation (as opposed to being grazed in common by a number of stockmen) they have been treated variably over the centuries, depending on altitude and the proportion of bare rock at the surface: that treatment ranging from simple liming to wholesale ploughing and re-seeding in rare cases.

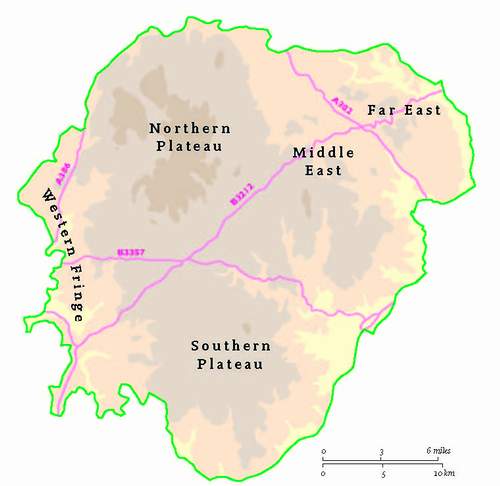

MIDDLE EAST AND FAR EAST DARTMOOR

(The appellations used in Figure 13, below, are my own, but the National Park does fall naturally into five topographic divisions for which the main roads, all original turnpikes, provide a convenient guide – though only that. They are not boundaries. This sketch map offers a reference for the rest of this book.)

At slightly lower levels just outside that figure-of-eight of damp peaty soils, narrowly along the western edge, but much more extensively to the east of the high plateaux with their Yes Tor to Western Beacon north–south axis – and, significantly, right within their rain shadow – the granite bears much more amenable soils from the cultivable point of view. ‘Brown earths’ in the pedologists’ language (and named by them here the Moretonhampstead and the Moorgate Series), they are the basis of the early enclosure and historic mixed farming of most of this lower and largely eastern Dartmoor landscape. (The low

FIG 13. A division of the National Park into topographic areas for our purposes. The roads are simply markers, not boundaries.

western fringe of the National Park also bears a narrow strip of such soils though here its prevailing rainfall is only mitigated by altitude.) On the brown earths lie all the villages that are within the granite boundary except Princetown (a specialised nineteenth-century imposition) and Lee Moor (the original but historically recent labour dormitory for working china clay). Almost all the rest are recorded in the Domesday Book so are certainly more than 1,000 years old. Here, also, there are a multitude of living and working farmsteads still: some now the lone representatives of whole eighteenth-century hamlets like Babeny, others still grouped physically and by name like the Drewstons near Chagford, where one farm is active. There are the remains of many others nearly at ground level and now ‘waste’ in the proper historic sense. The Houndtor medieval village is a classic of the genre, however it is but one of many as Fig. 218 demonstrates. Challacombe and Blackaton Down bear such sites.

A good, and wider, demonstration of that particular historic land-use change is on Holne Moor, nowadays the major part of a broad common rising from the right bank of the Double Dart to Ryders Hill the highest point of the southern plateau (Fig. 14). Archaeological survey has revealed its total enclosure between 300 and 350 m OD at more than one phase of farming history from the Bronze Age on and with at least three mediaeval farmsteads at its centre. Below the once-enclosed belt the land falls steeply another 100 m to the river and is clothed in ancient and coppiced

FIG 14. Looking north across Holne Moor from Ryder’s Hill. Combestone Tor is in the sunshine, Dartmeet is beyond it and the north plateau forms the skyline.

oakwood on granite clitter; above it, moorland with no vestige of modern enclosure rises to the summit at 550 m. While there is no evidence of a continuous physical boundary between the wood and the contemporary open common, there seems to have been a pretty precise and straight line at the upper edge of the old enclosures – itself a Bronze Age construction. Above that line peaty soils dominate, whereas they are only in isolated patches below it.

The largest ‘island’ of poorer soils, east of Widecombe, with other outliers west and southwest of the village, also bear evidence of prehistoric and historic enclosure. Like Holne Moor they carry a mosaic of brown earths and peatier soils, and on the open land bracken, a choosy plant, will often tell you where the brown earths are. Here, with the exception of blanket bog, is a microcosm of the whole Dartmoor soil pattern, even twenty-first-century land use reflects it. Perhaps because of its smaller scale and the juxtaposition of less extensive wild patches between field-patterned valleys, it is enormously popular with both regular visitor and newcomer. Stand on bare rock and stare at a wild skyline or struggle through heather and gorse and shoulder-high bracken briefly, but turn round and there, just below, are the reassuring fields, a village, even men at work, to make ‘holiday’ feel real (Fig. 15).

This eastern ‘half’ of gentler Dartmoor itself has two parts – separated by a trough from Chagford through Moretonhampstead to Bovey Tracey whose origins will be explained. The ‘far’ east is a small plateau-like quadrilateral perhaps 16 km

by 6.5 km, with the Teign valley as its eastern boundary. The ‘middle east’, although extended north to Whiddon Down, is centred historically and geographically on Widecombe, on which converge many of the roads and paths that cross and re-cross the patch. Widecombe’s fame in fable and primary school singing means that those routes carry as heavy a load of visitor traffic by vehicle and on foot as any in the National Park. A large proportion of the total number of annual visitors, then, are treated here to a sample of all the components of the Dartmoor natural scene except those of the high and remote wild country where peat creates the long view and provides the feel of the land underfoot. Even here, quite close to the road and certainly in cotton-grass flowering time visible from it, are all sizes of those valley mires: at Blackslade due east of Widecombe, in Bagtor Newtake or Halshanger Common (seen in Figure 16) either side of Rippon Tor and downstream of Challacombe. Here too are famous tors like Haytor and Hound Tor and lesser-known ones like Yar Tor and Sharp Tor, Bench Tor and Beltor, Chinkwell and Honeybags, Top Tor and Pil Tor, Saddle Tor and Bonehill Rocks.

The Webburn and its East and West headwaters that drain the ‘middle east’ are crossed by roads many times, famously at Ponsworthy Splash and Buckland Bridge, but also at Cockingford, Shallowford, Cator and Widecombe itself. Water is magnetic to visitors – it is to paddle in, even sit in on a hot day (Fig. 17). Tors

are to clamber on, see from or just marvel at. A bright mix of ling, bell heather and western furze flowering together and the odd bilberry to find in late August, russet bracken dying at half-term in October, short-cropped grass near the cattle-grid or car park all the year round to run across, kick a ball or just sit on – all creates the human habitat contrast with their own at home that visitors appear to crave. The ‘middle east’ encompasses all the characteristics of ‘lower’ Dartmoor, that which surrounds the old high and wild heartland, which in contrast, beckons the intrepid, the energetic and the forever challenged. It is too, remember, in the rain shadow of that heartland.

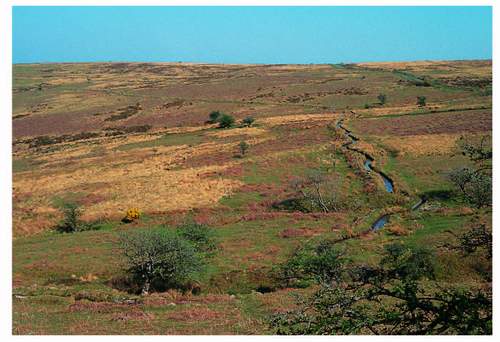

A fairly dense pattern of streams in lower Dartmoor was still not enough for the eventual density of the need for water. Leats – or water channels of the lowest possible gradient – were engineered (‘to lead’ is from the same root) to run from streams along near-contours to water fields and drive mills, and on their way to pass through villages as pot-leats and town gutters (Fig. 18). Sometimes they branched to pass even through scullery sinks to yard troughs and the lagoon beyond the midden. They accidentally but valuably add a slower dimension to the scope for freshwater living by plant and animal. Here, as Chapters 4, 5 and 6 will show, is a rich flora and fauna unused to swift currents. Their leaks and overflows create tiny mires where the plants otherwise content in valley mires can also

FIG 18. Holne Moor leat from the west. It is fed by the O Brook and snakes along the contour right across the common towards the parish fields.

flourish. They need constant attention by their users if their original function, or even part of it, is to persist. They are not confined to eastern Dartmoor, nor yet are they all domestic. The slopes of the high moor are themselves contoured by leats whose names as often as not tell their termini – ‘Grimstone and Sortridge’, ‘Prison’ and, largest of all, ‘Devonport’, begun by Francis Drake to water the ships and provide the power in his new dockyard. The early watermen organised the use of Dartmoor’s hydrological bounty by hand with a sophistication to make modern engineers and their equipment look innocent. There is not a stream in the whole National Park that has not contributed to this early lending of its water for temporary human use. Their own gradients and those of their valleys’ steep sides have always aided the leat makers.

It is on those valley sides too that Dartmoor woodland has persisted through postglacial time. The intensity of Bronze Age enclosure following Neolithic and possibly even Mesolithic settlement proclaims a clearance of prehistoric woodland that surrounded the blanket bog from all the manageable surface slopes. Wood – accidentally or deliberately – was maintained as the most useful crop on rock-strewn and precipitous valley sides. After all, it was already there – the natural climax of the Holocene vegetation succession. Having made room for food

FIG 19. The oakwood-covered sides of the West Webburn just before it joins its East counterpart at Lizwell Meet.

production and hunting space by removing trees, some better be kept for fuel at least and for domestic construction. Weather and soil poverty since might only support scrubby oak, ash, rowan and birch, but firewood, charcoal and tanning bark do not rely on shape or bulk. The relative density of zig-zagging but still steep packhorse paths and charcoal burner’s hearths in Dartmoor’s valley woodlands more than matches, in-like-for-like space, that of leat and pond out in the open.

Mid-twentieth-century forestry with financial incentive and hydraulic power achieved conversion of some such sloping woods to conifer plantation, notably along 6.5 km of the south side of the Teign valley between Whiddon Park and Clifford Bridge, but oak and ashwood still dominate the sides of the Double Dart, the lower Webburns (seen in Figure 19), the middle Teign, the Bovey and the Wray – all in the east – and the Walkham and lower Tavy in the west. The National Park thus has its share of classic British upland oakwoods, with mossy boulders and fern-with-bilberry floors and the characteristic bird assemblage that flits from here, at the southernmost end of its range, through the Marches to the northern Pennines.

Conifer planting was not confined to the valley sides in the headier days of early national forestry. Indeed, in the mid-nineteenth century the Duchy of Cornwall’s resident land steward had planted conifers in Brimpts Newtake alongside the Ashburton-Two Bridges road above Huccaby in a rather late reaction to the timber shortages of the Napoleonic Wars. The Duchy was for the time being then without a Duke – who only exists when the monarch has a son. He who will become Prince of Wales when he reaches his 21st birthday, but is Duke of Cornwall from his birth. The present Duke of Cornwall’s great uncle decided that he should do his bit for the timber reserve which the First World War had exposed again as inadequate, and replanted Brimpts which had been felled during that war and began plantations at Fernworthy and Beardown. The new Forestry Commission had advised him and in 1930 he leased Brimpts Plantation to it and threw in more newtakes, at Bellever, Laughter Hole and at Soussons, for planting too (Figs 20 & 21). Together with that Teign ‘valley side’ conifer plot of the 1920s and early 1930s and Plymouth city’s plantation around the head of the Burrator Reservoir in the Meavy catchment, Dartmoor suddenly, in relative terms, bore more than 2,000 ha of plantation, nearly matching the broad-leaved cover in area. That planting is now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, well into its first harvest. The hitherto extensive dark blocks of seemingly even-aged and dense conifers are broken up, light is round every corner, and replacement planting is more sophisticated, informed as it is by landscape architects and a need to meet public aspiration.

FIG 20. Bellever Forest from Yar Tor, a hint of Brimpts conifers is in the left middle ground.

PUBLIC OPINION AND THE DARTMOOR STAKEHOLDERS

That aspiration is itself a complex consideration in Dartmoor, incorporating as it does the desire of some walkers to use well-drained forest rides if only to get to high moorland more quickly and still dry-shod; that of others to walk the dog where chaseable sheep are technically absent; and those of the birdwatcher who knows there should be species here that occur in no other habitat in the Park. None of them may be adversely exercised about the high plantations placed here at all. But there are those who, viewing from a distance, see the hard cliff-like boundary of a dark cover and alien colours in a moorland landscape, and wonder why.

There is also of course the sizeable army of Dartmoor devotees and defenders for whom anything intruding on moorland, since their original predecessors defeated the enclosers in the nineteenth century, should be confronted. I do not mean to disparage them. Most belong to or look up to the Dartmoor Preservation Association – the oldest ‘amenity’ society in the country. Founded in 1883, to fight the enclosure of common land, by the serious if amateur moorland ‘students’ of the day, it persists as the focus of careful examination of proposed developments of all kinds. Its vigorous protest campaigns against any organisations or individuals who appear to it to be wandering from the straight and narrow, dominated the Dartmoor political scene for most of the second half of the twentieth century. For a large part of that time it was led and its representations marshalled by the granddaughter of its best-known founder Robert Burnard, one Lady Sayer. She was the scourge of farmers, foresters, quarrymen, civil – especially water and road – engineers, of generals and even of the National Park Authority (NPA) when its professed pragmatism appeared to her, in the sort of words she would use, to be ‘snivelling cowardice’. She fought for national park status, and sat on the Park’s first committee. No modern history of Dartmoor would be valid without reference to her, but quite naturally reactions to her actions and statements divided the world of Dartmoor stakeholders for 50 years.

A rival in the ‘Dartmoor leadership’ stakes through the second half of the twentieth century was Herbert Whitley of Welstor, above Ashburton, who founded the Dartmoor Commoners’ Association (a federation of local associations) in 1954 to give evidence to the Royal Commission on Common Land which sat from 1955 to 1958. In 1974, there still being no sign of promised national legislation to give effect to its evidence, he persuaded the new NPA to share with his Association the effort to bring order to the use of common land on Dartmoor by seeking ‘private’ legislation. An 11-year-long campaign finally delivered the Dartmoor Commons Act in 1985. It created a Commoners’ Council to protect and manage the use of the commons and gave a right of access on foot and horseback to the public in perpetuity. (Until then all the wanderers on most of the commons were trespassers in law, the commons did not constitute a statutory ‘open space’ and therefore things like the Litter Act did not apply.) The partnership that achieved the 1985 Act was recognised within it. Elected commoners were to regulate commoners and be responsible for their activities, protect their rights and the commons; the NPA was to take responsibility for the behaviour of the public, now at large on the commons legally. Nether would act formally without consulting the other. The detail is in Chapter 9.

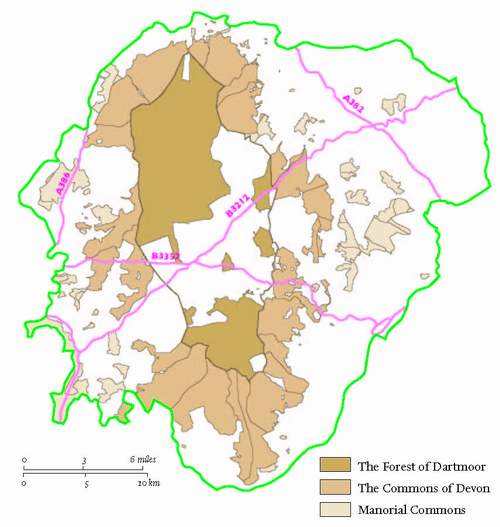

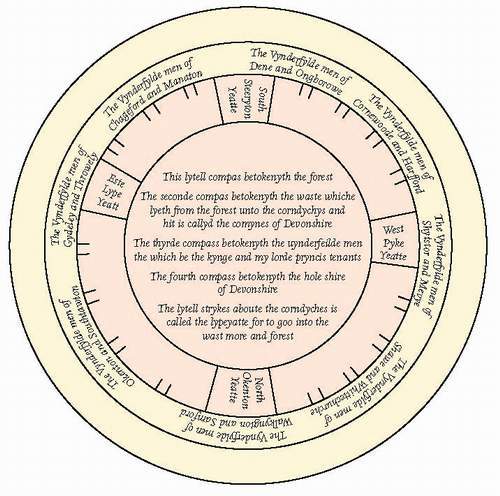

Common is still the legal status of much the greater part of Dartmoor’s moorland and half of the whole national park. Its core is an ellipse with a north–south axis from Cullever Steps to just south of Redlake and only 7.2 km across at its widest point. That core is still called the ‘Forest of Dartmoor’. It technically became a ‘chase’ in 1225 when the monarch gave it to his brother the Earl of Cornwall. (If it wasn’t the King’s, it couldn’t be a Forest.) The earldom eventually became the Dukedom under Edward III, and he passed it to his son (the Black Prince) and the eldest son of the monarch still retains it. In 1967 the Duchy decided not to object to the registration of the ‘Forest’ as common under the Commons registration Act of 1965 and so it is, oddly, the youngest of the Dartmoor Commons. It has some outliers such as Dunnabridge and Riddon Ridge and the two main blocks are separated by Princetown, the Prison Farm and a belt of nineteenth-century newtakes. The commons that abut the Forest are called the Commons of Devon, and most Devonians had the right to graze them until the last century. Now only those who have undisputed registrations under the 1965 Act have that right. There is then an outer scattered ring of manorial commons, some detached from the main mass. To complete the moorland picture, almost all of that which is not common is enclosed, sometimes in very large parcels, the later ‘newtakes’ already named. Most of the area involved was enclosed under Duchy authority and other landowners used the Enclosure Acts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The process had its origins however in Forest law, and smaller enclosures had been (legally) newly ‘taken’ from the Forest probably from Saxon times but certainly by Duchy tenants from the fourteenth century on, as a right at the change of a tenancy generation, for instance. The niceties of the common and newtake relationship will be expanded later.

FIG 22A. The distribution of common land: a cartogram dated 1541, made for a commission inquiring into Buckfast Abbey land and rights after its dissolution (DoC).

FIG 22B. The distribution of common land within the National Park in 2009: the angular white belt across the Forest includes the Ancient Tenements and all the newtakes.

To return to the Dartmoor ‘stakeholder’ story, there are of course many other such contemporary groups, though neither commoners with a 5,000-year background, burghers of the stannary towns of Ashburton, Chagford and Tavistock with a 1,000-year one regulating the marketing of tin, or even environmental campaigners with only a 150-year one would regard them all as particularly worthy aspirants to that status.

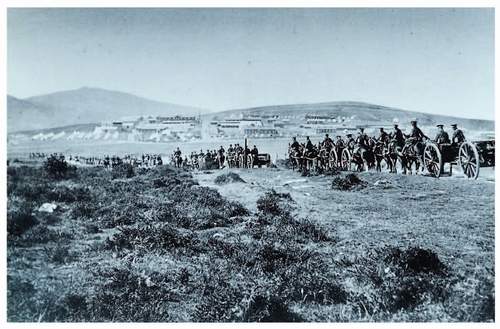

Military men in all their guises have been here nearly 200 years, off and on for the first 100 but now occupying some 9,193 ha as live firing ranges – though, since 1996, only firing small arms and mortars rather than the artillery which was their original motive in the nineteenth century. They also use another 3,850 ha or so for

‘dry training’. Water engineers have created eight reservoirs and one pumping extraction from a large mire, Taw Marsh, and, while they had remarkable antecedents as we have seen, only began their ‘modern’ operations at the end of the nineteenth century, perhaps 90 years after the soldiers. Domestic and industrial water from high rainfall areas seems logical enough and the early leat builders showed how old the logic is, but interestingly they drew or ‘led’ it off, they didn’t try to store it up there. The lower down a river system water can be stored the easier it is to keep the storage topped up – and the River Dart, which has only one small Edwardian reservoir in its catchment, is now tapped at Totnes through its floodplain gravel just above its tidal high-water mark.

The foresters have been spoken for already, and the china clay extractors have been now confined to the biggest of the three outcrops of kaolinite on the southern moor. Since the 1990s they are outside the National Park after a boundary review, of which more anon. There have been many other mineral extractors from prehistoric times onwards and their details will also be revealed, granite and its associated metalliferous ores were their prime targets and none is worked now. A brave few toyed with the commercial extraction of peat and oils from it, and even braver souls, the agricultural improvers, thought they might plough after blasting rocks out of the way. Only the Prison Farm (now divided up among other farmers) is testimony to what improvement might be possible, and that with free labour. In the nineteenth century Duchy leaseholders, ignoring climatic truths, contemplated growing large acreages of flax, rye and other crops alongside the turnpikes. The two main turnpikes are the so-called ‘scissor’ roads that cross Dartmoor from Moretonhampstead to Yelverton and Ashburton to Tavistock and thus each other at Two Bridges, already portrayed in Figure 13. They were almost certainly the creatures of those improvers. While in plan they might have looked as though they would shorten some journeys, their investors’ motivation was exploitation of the open land.

So, the Moor over 5,000 years has seen many ‘stakeholders’ come and many go. There are clearly honourable exceptions to the going, and the hill-farming commoners and Forest tenants take pride of place in that, for the longevity of their stay and their own tenacity. The Duchy of Cornwall can also stand up to be counted as it’s been there, if originally as an earldom, for some 750 years, and still takes its responsibilities very seriously. If one wanted an example of environmental benevolent despotism at its best then the Duchy on Dartmoor is it.

But since the mid-nineteenth century the new ‘stakeholders’ in Dartmoor, now the numerically vast majority, are ‘the visitors’. Many different groups in society make the millions of visits that populate each year, and they will also be analysed. In many ways they have been represented on the spot by the NPA since 1951. It exists to promote their understanding and enjoyment of all the special qualities of this wonderful place and of course to conserve and enhance those qualities for the nation. These two purposes, written in reverse order in the statute, exist because those who wanted a stake in the most beautiful areas of England and Wales mounted a sufficiently effective campaign in the 1930s and 1940s to persuade society and its government that those areas and access to them should be protected from potentially damaging development. The history of that protection and its evolution through the last 50-odd years is a story in itself to be told in Chapter 9, but its firm establishment is now clear for all to see.

The oldest stakeholders – the commoners – now have a partnership with the youngest – the NPA. Their shared purposes, as we have seen, are enshrined in the Dartmoor Commons Act of 1985. They effectively take joint and several responsibility for the management of the moorland and of its visitation. The Commoners’ Council manages the agricultural use of the commons and protects them and their commoners against most if not all ills. The NPA manages visitors’ activities whether they are from just over the boundary every weekend, or once a year from all over the globe.

Even at this stage in this book it would be wrong to leave things just like that. National Park Authorities have had to have due regard for agriculture since 1949; the Commoners’ Council is enjoined by law to take natural beauty into account

FIG 24. A true commoner’s daily business – ‘looking at’ stock. Highland cattle and their owner on the south slope of Cosdon. The inevitable Hay Tor on the far skyline, one of the ‘long views’ for which Dartmoor is renowned. (T. Eliot-Reep)

when making its own agricultural decisions. Since 1995 NPAs have had a duty to foster the social and economic well being of all the resident communities in their parks and Dartmoor NPA is no exception. Its working relationship with the commoners is clear. There are many farmers within the Park who are not commoners, but various incentives exist to tie their management into the national park purposes and many in that way participate in the pursuit of them. The County Council and the Districts (soon perhaps to be combined as a Unitary Authority) and parishes that overlap the park or lie entirely within it have representative seats on the NPA. By this means – and those seats add up to a majority – the communities within the park have a considerable say in its governance and management. The Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs appoints folk to the remaining 12 seats to represent the national interest and strives in doing that to strike a balance between those who might defend the landscape, those who represent those seeking access to it and those who own and work it. Most of them will be locally based and thus wear more than one hat. The NPA is the planning authority and thus regulates land use change and the appearance of structures in the landscape. It is empowered to aid and abet communities and individuals in their own endeavours when a wider interest and public benefit can be identified within them. Such benefits can range from the perception of upland vegetation in good condition to the visitor facilities in a well-kept village. Ideally local resident, visitor and land manager should all benefit from a benevolent NPA that acts as catalyst for mutual betterment and regulator of individual selfish excess. In its duty towards wildlife the NPA is itself aided and abetted by Natural England, offspring of an uneasy marriage between the Countryside Agency and English Nature. It is technically in loco parentis to an NPA and has staff in the region with responsibilities for nature reserves, other protective designations, and the administration of agri-environmental schemes to reward farmers for conservation work. Likewise English Heritage and the Environment Agency do their thing in Dartmoor that supports the NPA in its work and helps it towards the fulfilment of the statutory National Park Management Plan.

So, many hands are employed in one way or another in maintaining the surface appearance of this southwestern hill in the twenty-first century. It is in the nature of these things that motives vary and mutual understanding is thought at times to be unlikely, even impossible. That ramblers and hill-farmers may share a real objective – in having vegetation below knee height – may not be acknowledged for decades for quasi-political reasons. But things change. Just as King John agreed to give up hunting throughout lower Devon in 1204, and by chance drew the boundary of Dartmoor’s heartland, so the commoners conceded a right of public access to the commons in perpetuity in 1985 and agreed to trust the NPA to manage public recreation on them. The NPA recognised formally, at the same time and in the same instrument, that the commoners could be trusted to manage the commons, now including the Forest, by going about their own well-understood business.

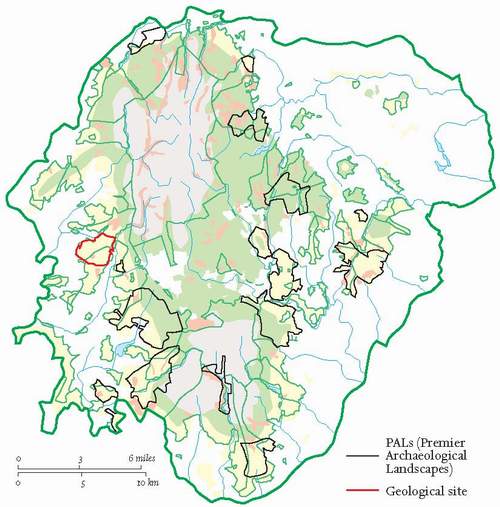

Since then there have been massive changes in the relationship between farming, landscape and its enjoyment – largely through European consensus. The payments for production and protection of ‘public goods’ are now a potential part of every farmer’s balance sheet – not least in national parks, though not as good a part as they were a decade ago. In 2005, the farmers of Dartmoor’s moorland persuaded the NPA to get all the other agencies for particular ‘public goods’ together with them and agree, and sign up to, a shared ‘Vision’ for that moorland in 2030. The sharing was the crucial need. The map of that vision, essentially a broad-brush portrayal of vegetation communities with ‘premier archaeological landscape’ insets, bears the signatures and logos of English Nature and the Countryside Agency (now together as Natural England),

FIG 25. The Dartmoor Vision for the farmed landscape of 2030 AD. See Figure 79 to show only the vegetation in other colours. Here the black outlines are premier archeological landscapes (PALs), the red one is a geological site. (DNPA)

English Heritage, the Environment Agency, DEFRA, Defence Estates, the NPA and the Commoners’ Council. Here is as powerful an alliance to assure the future welfare of the moorland as has ever existed. As always that future, and the security of the moorland farmers, without whose work nothing will be done, demands a proper investment by society in the joint achievement.

The Dartmoor Vision and the process by which its underlying consensus has been achieved are already regarded as a model for other national parks – if not all upland blocks. It will be referred to again more than once as this latest general update on the state of Dartmoor proceeds.