CHAPTER 4

Dartmoor Vegetation in the Last

Millennium

The whole surface of Dartmoor, including the rocks, consists of two characters, the one a wet peaty moor or vegetable mould, but affording good sheep and bullock pasture during the summer season. The other an inveterate swamp absolutely inaccessible to the lightest and most active quadriped [sic] that may traverse the sounder parts of the forest.

The most elevated part of the forest…consists of one continued chain of morass answering in every respect the character of a red Irish bog. This annually teems with a luxuriant growth of the purple melic grass, rush cotton grass, flags, rushes and a variety of other aquatic plants.

The depasturable parts of the forest whose spontaneous vegetation, among many other herbs and grasses consisted of the purple melic grass, mat grass, downy oat grass, bristle leaved bent, eye-bright, bulbous rooted rush, common termentel, smooth heath bedstraw, common bone binder, cross-leaved heath, common heath or ling (dwarf), milkwort, dwarf dock and the agrostis vulgaris in very large quantities. The disturbing of this herbage however inferior it may appear to the refined agriculturalist is on no account whatever to be recommended or permitted.

Charles Vancouver, 1808

Vancouver was reporting to the Board of Agriculture 800 years into the millennium of the chapter heading, and speaks of ‘the forest’ as though encompassing all the moorland out of a deliberate deference to its owner. But his observation of the surface, its plants and its agricultural use or potential would not go amiss today, and could probably stand for a few hundred years before he set it down. After all, he was writing when the ‘Little Ice Age’ was still running so the flora he lists was clearly surviving it, and there is no evidence that the relative warmth of the fourteenth century had changed the moorland character in the general sense. What is underlined here is the persistent interaction of human activity and even the highest moorland, a relationship begun in the Mesolithic, nearly 10,000 years before him and still, just, going on today. Clearly man did not stop manipulating the vegetation of Dartmoor when the tinners felled the last high moorland alder. Throughout historic time, under a series of economic, environmental and often repetitive pressures, hill-farming man has moved the moorland boundary up and down. He has sometimes enclosed and ploughed moorland for an exclusive use and let some of it go to ‘waste’ again, not literally but as ‘waste of the manor’. He has intensified and then relaxed the ‘improvement’ of moor and meadow, inserted plantations into moorland enclosures and valley-side broad-leaved woods and planted new deciduous copses again. In the very early twenty-first century the advocacies for livestock production and the protection of ‘semi-natural’ things may be being reconciled for the first time. While that means that the effort on both sides may be halting and the agreed formulae still in the test-bed stage, farmers, ecologists and their shared political masters are rubbing shoulders after more than 50 years of, to underplay the situation, hostility. The national park status of Dartmoor, locally unpopular still in some parts, has in the end become a catalyst for this convergence of quasi-scientific thinking and traditional irreplaceable skill, as will be steadily revealed. At the beginning of the twenty-first century dedicated Dartmoor moormen are, in a real sense, ahead of the game.

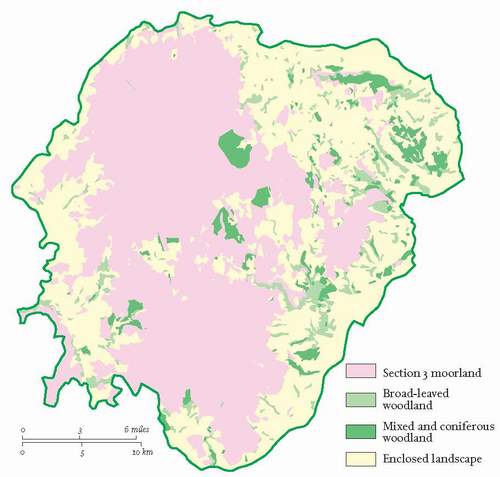

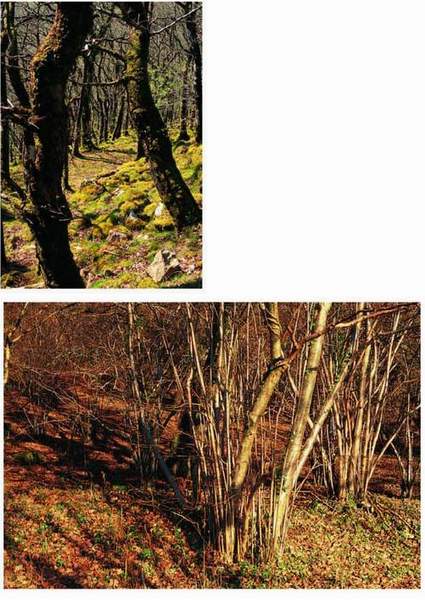

The prehistoric process had blocked out the general ecological pattern of the landscape within the National Park boundary by the clearance of woodland from all the upper lands of subdued relief and inadvertently created moorland. The Dark Age Saxon immigration completed the clearance of, and enclosed, the broader valley floors and gentler lower slopes, as the Domesday survey shows. Almost all the present-day parish names appear in the Domesday Book as manors, many with subsidiary manors still identifiable within them. So a second sophisticated land-use pattern and land-tenure system had been imposed on the whole Dartmoor landscape by 1,000 AD. Mediaeval men consolidated the general arrangement which left most of the woodland confined to the steepest and rockiest valley sides, indeed in some parishes the dimensions of woodland recorded in the Domesday Book accord very closely with the broad-leaved woodland standing today, largely because of that land use and terrain correlation (Fig. 78). Thus was the gross pattern of the vegetated landscape for the next 1,000 years established.

That pattern has three major components on which the distribution of the Dartmoor flora is based: the open and newtake moorland, the steep valley-side oakwoods, and the network of fields, walls, banks and lanes that comprise the farmland, or in-bye proper, which extends well upstream of the gorges in the

valleys of the Dart, the Bovey and the Teign. In the case of the Dart and its tributary headwaters this includes a broad spread across the central basin of Dartmoor as far upstream as Princetown, Postbridge and beyond Widecombe. Princetown became the base of an island of new nineteenth-century in-bye. A second near-island centred on Postbridge includes at least seven Ancient Tenements (see below) but has eighteenth- and nineteenth-century extensions which create tenuous links with the West Webburn and the Wallabrook valleys. In one sense they are paralleled by the larger conifer plantations at Bellever, Soussons, Beardown and Fernworthy, which as woodland ‘islands’ have been lately inserted into that mediaeval and Victorian mosaic.

Otherwise, the original woodland is the most clearly defined and to that extent the purest of the three gross eco-geographical elements of Dartmoor despite a few coniferous insertions, of which more anon. For as we have already seen the lower, eastern farmland, even that in the central basin, has within its compass islands of hill-top moorland of variable size, long narrow valley mires and bogs historically not worth the draining, and copses sustained through time at the occupiers’ whim. ‘Moorland’, too, is a generalisation masking a substantial variety of soils and plant communities. None of them individually of hugely rich biodiversity but taken together so different from lowland man’s day-to-day experience, that the complex forms a wonderful but unlikely raised oasis in the intensely cultivated ‘desert’ that is lowland England, even lowland Devon. From high blanket bog to spur-end heath the continuum of perceived open expanse, because the vegetation is properly below knee height, is the greatest delight that Dartmoor moorland offers to both the farmer at his newtake gate and to the Dutch tourist – there are a vast horde of visitors, local and distant, in between those two extremes. The tors that punctuate the edge of that open expanse also occur throughout the woodland and field landscapes, often so small that they pass unnoticed. In each of the three they provide a habitat variation all of their own for plants and animals.

We have already seen that the quotations from Vancouver’s survey at the head of this chapter, which are closely allied in his ‘Dartmoor Forest’ text (clearly currying favour with the Prince of Wales of the day), describe a flora we can recognise now. They also show that, although in one sense he almost over-generalised – did he merge blanket bog and valley mire in his ‘morass’ for instance? – in another he recognised subtle distinctions on the surface which we still see. He sought the little vertical exposures that showed him the deep peat of his ‘morass’ and the soil profiles under his ‘wet peaty moor’ as in Figure 77.1. He was clear that the high morass – or blanket bog – was still growing and he talks nowhere of eroded peat, except when dramatically describing ‘slope failure’ at the edge of that blanket bog. Some 200 years on, that may be the only discernible difference between our perception of the general state of the moorland and his. Elsewhere, just to complete the two-century comparison, Vancouver recognises the singularity of eastern Dartmoor, even making it a separate agricultural ‘district’ in his breakdown of Devon for survey purposes. It has, he says, ‘a grey loam lying on a coarse rubbly clay and granite gravel’ where cultivated, and moist peaty earth on a reddish brown clay where not. He noted also that the light-brown mould of many parts (of the district) ‘by judicious cultivation produced excellent turnips, barley, clover, wheat, oats and where too strong for permanent pasture, beans and pease’. The mixed farming that this statement implies, was still the farmstead base from which hill farming was conducted into the second half of the twentieth century.

THE MOORLAND

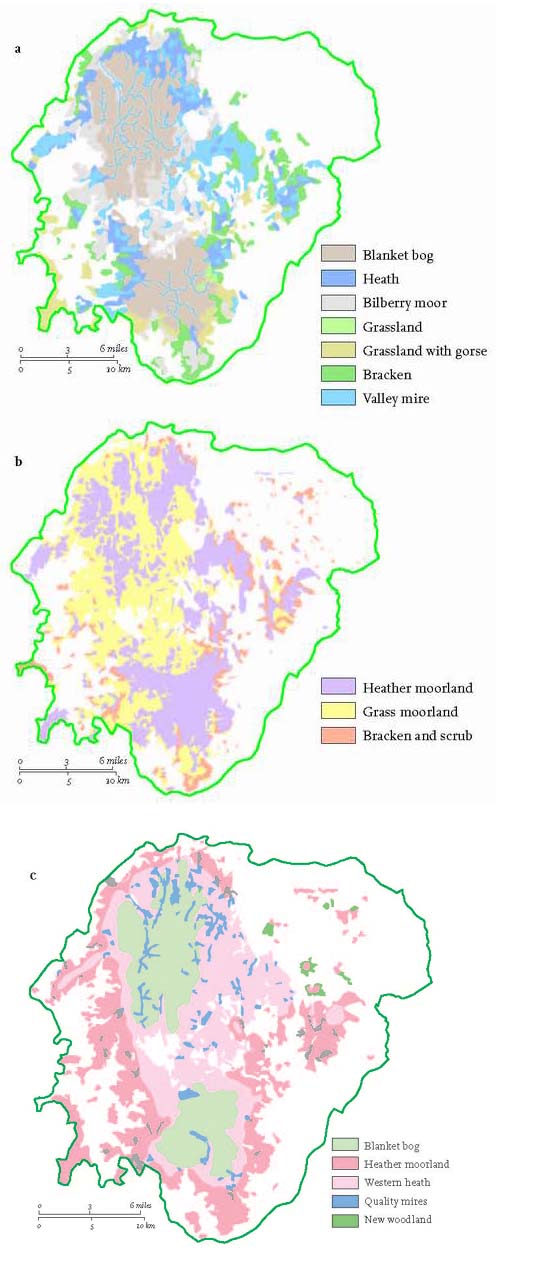

In the last 40 years there have been three attempts to portray the whole upland vegetation pattern comprehensively at a reasonable mapping scale. In 1970 the then Nature Conservancy decided to do some research into the effects of contemporary grazing and burning on Dartmoor and realised that a map of the vegetation was a necessary pre-requisite for that work. (A nice comparison springs to mind, with the need, at exactly the same time, to find out what was happening to bird predators vis-à-vis pesticides, which led to the need for a national common bird census.) The research team, led by Stephen Ward, then at Bangor, after that with Scottish Natural Heritage, used a combination of ground survey, on the basis of a systematic but random sample, and the analysis of aerial photographs in colour specially flown for the purpose to extend the survey, with follow-up ‘ground truthing’ of the photogrammetric analytical results. The vegetation was then subjected to an association-analysis separating vegetation types by the presence or absence of indicator species. The result was a ‘one-inch’ map of the open moorland superimposed on an uncoloured Ordnance Survey base and published by the Field Studies Council in 1972 (Fig. 79a). The survey itself had recognised nine vegetation types (one transitional between heath and grassland and not mapped separately in the end). It was also decided that while the heather/purple moor grass type was readily distinguished from blanket bog in the field it could not be safely interpreted as different from aerial photographs. Its mature version was thus lumped with blanket bog and its ‘over-burnt’ state with grass or heath. So the final map shows seven vegetation types: blanket bog, heath, bilberry moorland, grassland, grassland invaded by bracken, grassland with gorse, and valley bog. Ward made it clear that the identification of ‘communities’ would involve a more detailed analysis of each ‘type’, and also pointed out that the result could be described as a map ‘of vegetation potential’ which relates it well to the latest attempt published in 2005 (see below).

In 1994, the Agricultural Development Advisory Service (ADAS) – still then part of Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) – given the prospect of financial agreements with hill-farmers and commoners’ associations involving vegetation management under the designation of Dartmoor as an Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA), made a ‘land-cover’ map of the whole national park (Fig. 79b). The mapping extended on to the east side of the Teign valley, in the northwest between Sourton and Lydford, south and southeast of Tavistock and in the extreme southwest to envelop the china clay workings at Lee Moor, the whole reflecting the Dartmoor Natural Area rather than just the National Park. It did not attempt to show blanket bog as a separate category of land cover, the whole of the ‘blanket’ was subsumed under grass moorland or heather moorland, which echoes Ward’s difficulty but chooses the opposite outcome. Not really surprising given that the target was a grazing regime. This map, too, was made from aerial photographs. The only other category which falls under our moorland heading is ‘bracken and scrub’ largely confined to the eastern fringes of the moorland all the way from north to south and in the southwest, especially on Lee Moor proper, east of Burrator reservoir woodland and the northern half of Roborough Down. There is no reference to gorse of any kind.

It has to be noted here that between the 1970 (Ward et al) and the 1994 (ADAS) dates, in 1983, the Soil Survey published a map at a ¼ inch to the mile of the ‘Soils of South West England’ whose contribution to this list is its portrayal of blanket peat. Given the difficulties revealed, or soft options taken (!), by ecologists, perhaps the soil scientists’ mapping of deep peat will give us the best approximation of the true boundary of the blanket bog at a small scale (see Fig. 76).

In 2003, farming commoners’ muttering about the confusion (my translation of their view) caused by different government agencies bringing different messages about moorland management to their kitchen tables, triggered in the minds of the National Park Authority (NPA) the thought that convergence in that advice might be brought about by facilitating debate first amongst the agencies and then between the agencies and the commoners. The NPA had already set up a Hill Farm Project and had recruited to it one John Waldon, who set about getting all the local representatives of English Nature, English Heritage, the Environment Agency, the Duchy of Cornwall, the Ministry of Defence, the Rural Development Service of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the NPA together and persuading them that they ought to be able to agree a map of the vegetation pattern they could share as a vision for Dartmoor 25 years hence. In 2005 that map (or properly, cartogram, for its divisional boundaries are not precisely transferable to the ground) was published (Fig. 79c).

The map – entitled ‘A Vision for Moorland Dartmoor’ – is by a broader brush than the Nature Conservancy had used 35 years earlier, and ended up with five vegetation categories: blanket bog, heather moorland, western heath, (selectively) mires of high ecological quality and naturally regenerated woodland. The fact that it is a visionary map may explain the last category, and the area of woodland ‘invasion’ on it is tiny, but its existence probably satisfies some ‘re-wilding’ purists. More significant is the fact that three of Ward’s vegetation types are rolled up into ‘western heath’ on the ‘Vision’ map and they were all grassland variations in his analysis, although in his text he says of them ‘heather is always present’. It is a matter for conjecture whether or not the ‘Vision’ group see pure grassland – or

FIG 79. Three attempts to map the open land, made with different motives over 33 years – for comparative purposes only. (a) – The Vegetation of Dartmoor (after Ward et al, NERC/FSC, 1972). (b) – Landcover (after ADAS, 1994). (c) – ‘The Vision for 2030’ map (vegetation only, after DNPA, 2005). For the complete ‘Vision’ map see Figure 25.

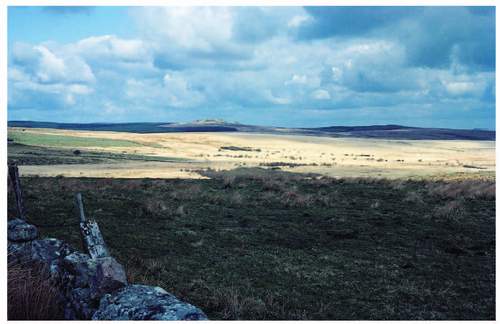

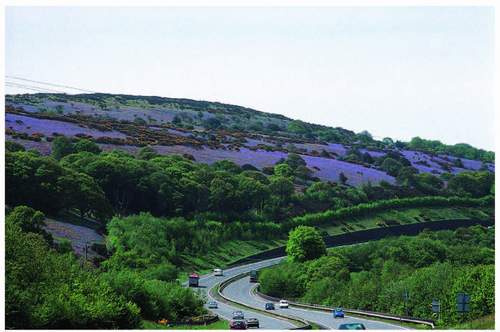

even grass moor – as a less than desirable component of the Dartmoor scene in the future. Most moorland travellers now would point to a much greater hectarage of apparently grass-dominated space than that clearly dominated by any other, while all can also point to more confined areas they see as dominated by heather (properly ling Calluna vulgaris) – Bush Down say (Fig. 80); bracken – Green Coombe as in Figure 95; or gorse – Whitchurch Down (Fig. 81). The ‘Vision Group’ seem not to have had the same difficulty as Ward in identifying heather moorland – for their own purposes admittedly – which probably also accounts for the size variation in areas of blanket bog between the two maps. Ling, usually called heather in this context, it is fair to say, has become a symbolic plant in much ‘conservation specialist’ thinking. Thus its restoration is now a target and a measure of success for lonely ‘official’ fieldworkers, especially when they meet. Yet

FIG 81. European gorse and short-cropped grass on Whitchurch Down (see also Fig. 7).

many ecologists will point to heather-dominated stands of vegetation as among the least species rich. Like the whole of Dartmoor’s moorland it is the contribution it makes to overall southwestern biodiversity that matters.

‘Western heath’ was not a name used by Ward, but it is clear that the current visionaries wish it to be a mosaic of heathers, western furze Ulex gallii, grassland and a gradation between wet and dry heath each with its own indicator plants, all under this single heading. Suffice it to say that, as ever, for the purpose of appreciating the present organisation of plant communities one should extract from these three maps – produced after very different motivation – whatever is most helpful. Ward had his critics, and many a local botanist thought that he extended the blanket bog too far down some slopes and made continuous mires where in reality the relevant valley floor contained a chain of separate ones. Such is the difficulty of interpreting even good colour aerial photographs at a 1:10,000 scale – and to be fair to Ward, he points out that his ground sampling grid of quadrats was never going to ‘catch’ a representative set of examples of linear features such as the valley mires.

There are now of course satellite images of Dartmoor in colour, of which those in infra-red form are most helpful. Despite their reproduction scale, even the sites of individual recent fires can be identified within heather moorland for instance because ironically they are ‘cooler’ than the heather itself. This gives an idea of the potential for picking out some detail, though the coincidence of the ‘temperature’ colour of pure heather stands and conifer plantations, say, indicates the limits of that potential for someone who doesn’t know the ground.

In the same time frame – roughly the last quarter of the twentieth century – the National Vegetation Classification (NVC) – a comprehensive attempt to classify and describe British vegetation – was conceived, gestated and born. The fieldwork began in 1975, was published in five volumes between 1991 and 2000, and is now widely accepted as the standard system for the classification of plant cover in Great Britain. It forms the important background, for our purposes, to An Illustrated Guide to British Upland Vegetation published by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee in 2004. That single volume reveals that Dartmoor has 30 of the NVC upland open vegetation types at the community and subcommunity level. These two levels are grouped into mires (M) – subsuming bog in all its forms – of which Dartmoor has 16 of the national 38; of heaths (H) 5 of 22; and of acid grasslands and montane communities (U and MG) Dartmoor has 9 of 21. There is also listed a bracken-with-bramble ‘underscrub’ (W25) that might be said to be developing now on some of our moorland fringes.

At this point it is important to reflect that all those upland vegetation surveyors concede that there is a general ‘natural’ simple sequence upward of woodland, dwarf shrub heath, grassland and blanket bog, and that the last three are all punctuated by small bogs on level ground and mires wherever water is at the surface more than temporarily. They also seem to concur that, despite the origin of the middle two members, the sequence has been distorted by grazing and burning activity in the last 50 years. The special effect of this has been to insert grassland of variable character among the heath, lower down the altitudinal sequence than its natural position. Burning – or ‘swaling’ on Dartmoor – is also the partial explanation of Ward’s difficulty over the separation of heather/purple moor grass moorland from blanket bog at the latter’s edges, from the air. When this community is burnt or perhaps burnt too often or too slowly, its two prime distant visual characteristics are destroyed. The dark (all the year round) heather may be totally burnt away, and the white raffia-like purple moor grass (winter) litter certainly is. The tiller buds of the grass are almost fireproof deep in the bases of last year’s tussocks, so the green of young shoots dominates the distant prospect of a winter-burn site in spring, and then their rapid growth may shade out or otherwise setback stump shoots or seedlings of the heather.

All this explains why the greatest concern for moorland vegetation managers and their mentors now, and whatever their motive, is to try to reduce the burning of this heather/purple moor grass community over time whether it is overlapping the blanket bog edge or not. The same set of motives all point to an increase in

FIG 82. Infant heather on Bush Down after a fire in 1983.

cattle grazing in spring and summer to reduce grass dominance if the renovation of the dwarf shrub component of the community is an ambition (Fig. 82).

The good thing that emerges from a simple examination of the mapping exercises and the descriptions and the classification of the upland vegetation referred to so far is the general accord between them about the Dartmoor pattern. Moreover Ward points out that his map does not depart in any degree from the ‘verbal description’ of the vegetation by Harvey and St Leger Gordon in the predecessor volume of this book in the New Naturalist series published in 1953. Further, it is possible to fit the NVC types into Ward’s association analysis – the scientists of the Vision Group could readily tell you where those types sit on their map, and the farmers will still describe the main community of the blanket bog in Vancouver’s terms with a nod towards Harvey if necessary. Even so it is as well to remember, in the words of the authors of that Illustrated Guide to British Upland Vegetation: ‘just as a map is not the territory it represents, a vegetation classification is not the vegetation itself. Vegetation does not fall neatly into man-devised sub-communities, but varies through space and time. The boundaries that seem obvious to us may mean less to other animals or indeed to the plants themselves.’ However, for the layman enjoying the Dartmoor scene, some degree of perceptible organisation of the plants on the surface can only enhance that enjoyment and make the questions that surround contemporary management somewhat easier to grasp. Hence the discussion so far, now some detail.

The blanket bog

The bog surface of high Dartmoor’s two plateaux is now quite variable physically, and even at its smoothest somewhat threadbare. From the air a strikingly dense net of sheep tracks takes the eye (Fig. 83), and there are two kinds of micro-relief First, where erosion is clearly taking place, and although diminishing rainfall may slow down or stop peat development there are still storms, and gully erosion is more easily initiated in drying peat. Burning of bog vegetation if poorly managed, vandalistic or carried out under the wrong wind conditions, may dry or even burn the peat, and thus aid and abet such erosion. (The wind itself may move dry peat fragments on occasion in a kind of organic dust storm.) This gullying process can leave a set of mini-canyons separating small plateau-like blocks or ‘haggs’ that stand up to two metres above the gully bottom, around Cranmere Pool for instance. The other kind of micro-relief is artificial and arises from man’s use of the peat mainly for its qualities as a fuel. Peat digging for domestic purposes has been a right of common for at least 1,000 years and the evidence for it lies in small faces of peat where natural erosion is unlikely. They are often apparently irregularly distributed, as on Crane Hill and Great Gnats

FIG 84. Blanket bog surface, cotton grass, sphagnum and rushes; the formal lines of the Rattlebrook peat diggings can be seen on the far slope.

Head. The odd attempt at commercial exploitation of peat on the Forest in the nineteenth century, before it was legally a common, has left a rather formal pattern of parallel trenches in places, notably around the head of the Rattlebrook, itself a headwater of the Tavy (Fig. 84).

Gullies and trenches obviously aid the drying of the blocks that they neighbour. Their near-vertical sides are often bare of flowering plants and the relative dryness of the upper surface of the blocks may not be readily indicated by the plant cover. Ward talks of ‘constant species’ and certainly deer grass Trichophorum caespitosum, cotton grasses Eriphorum angustifolium and Sphagnum moss species are just that, but so are ling, cross-leaved heath Erica tetralix and of course purple moor grass Molinia caerulea. Indeed the ‘easy’ separation of this blanket bog vegetation (NVC M17) from the heather moorland (H10) on the ground depends upon the disappearance of deer grass and cotton grasses as one walks across the boundary. Another cotton grass – harestail E. vaginatum, tormentil Potentilla erecta, milkwort Polygala serpyllifolia and heath rush Juncus squarrosus can be common, and in wetter depressions bog asphodel Narthecium ossifraga (Fig. 85) and sundew Drosera spp. will show (Fig. 86). Some depressions may be the site of bog pools, even collections of them, sometimes covered by blankets of floating sphagnum with odd spikes of some of the flowering plants

FIG 87. Typical pool in blanket bog surface.

piercing the moss surface. In the occasional hollow sedges, especially beak sedge Carex rostrata, may dominate to the apparent exclusion of other plants, giving the site the appearance of a field of unripe corn as the sedge leaves wave processionally in the wind. The NVC classifies bog pools as M1 (Fig. 87), collections of them as M2 and sedge ‘meadows’ as M4.

On the gentler slopes of valley sides within the general plateau of blanket bog apparently pure stands of purple moor grass can occur – they are not pure, but the

grass is so dominant that that is the clear impression even when the observer is very close to or within the community. The upper Cowsic, the northeast slopes of Amicombe Hill, White Hill on the northern edge of the Willsworthy ranges, the middle reaches of the upper West Okement, Tavy Head and Chagford Common close to Fernworthy Forest bear such stands in the northern plateau (Fig. 88). Slopes above Fox Tor, and Cramber Tor and the plateau right across from Crane Hill to Ryders Hill in the south are similar. That list is not exhaustive but it shows how widespread is the phenomenon. Even some central newtakes are white with purple moor grass tussock and litter all winter – Muddilake, a valley mire in the angle of the ‘scissor roads’ immediately east of Two Bridges, is a good example (Fig. 89). In all, purple moor grass recognised from the air in 1970 covered 14,000 hectares, or around 35 per cent of the common land and higher level newtakes – including valley mire as well as blanket bog, and even some of Ward’s inscrutable ‘heather moorland’. On many a hillside clothed in darker vegetation such as ling the almost white winter grass will define a very shallow gully as though it were itself a stream flowing down the slope.

As has been noted already, burning too often, usually in March – to get rid of the purple moor grass litter and so expose new shoots soon after for spring cattle grazing – is one of the reasons for such extensive ‘fields’ of the grass within, and at the edge of, the blanket bog. The nature conservators’ mantra is that if cattle grazing could be intensified as a substitute for much of the burning, then the dwarf shrub members of the community would do better. But there is some evidence that stock relish purple moor grass less after midsummer (though cattle may return to it in the late autumn, however reluctantly, out of necessity), and only intense grazing in the latter half of the year will really affect the amount of ‘raffia’ present in the winter. Equally, the system that allows a hill-farmer to

maintain a good enough herd of the hardy stock and of the right number all the year round, to be profitable and to follow current nature conservation thinking about a regime for blanket bog vegetation management has yet to be devised. It is exercising the Vision Group as I write.

Grasslands and heath

Ward’s map demonstrates that in 1970 on some radial walks out of the blanket bog, grasslands would appear in their rightful altitudinal position – adjacent to it. This was especially the case on the southerly arc of the northern plateau’s edge from say Lydford Inner Common round to Great Stannon Newtake immediately west of Fernworthy Forest. But from Bridestowe and Sourton Common round the northern edge to Watern Tor on the outer boundary of Gidleigh Common, with the exception of the West Okement valley, no grassland intervened between blanket bog and heath. Interestingly, grassy islands occurred beyond the heath on Belstone and Throwleigh Commons. The grassland adjacent to the southern plateau blanket bog was then a very patchy fringe – most extensive in and around Foxtor newtake south of Princetown, and eastwards nearly to Hexworthy, with a little on Penn Moor near the head of the Yealm. Otherwise, through the Plym and Meavy headwater valleys and on Shaugh Moor, heath butted up against the blanket peat, as it did on Holne Moor to the east. As in the north there were significant islands of grassy moor at lower levels, some wholly detached like the south end of Roborough Down, Wigford Down and Hanger Down, others like the southern ends of Walkhampton, Harford, and Ugborough Commons were separated from the blanket bog by heath and bilberry Vaccinium myrtillis moor.

The ‘heath’ of the 1972 map was dominantly dry heath, with ling in the ascendancy then and cross-leaved heath and bell heather Erica cinerea present in the damper and the drier places respectively. Grasses were and are always present (a nice mirror image of the grassland types on the same map where ‘heather is always present’), especially bristle bent Agrostis curtisii. Bristle bent – bristle because of its thin wiry leaves – is a distinctive basally tufted but long-stemmed grass with a noticeably compact straw-coloured flower-head appearing to dominate the sward in June and July. The significance of bristle bent is that Dartmoor is near the northern limit of its range and while it occurs sparsely in South Wales, on the Quantocks and Bodmin Moor has some hectares of it, here it is much more widespread on gentler slopes of the drier peaty soils. Dartmoor is its British stronghold (Fig. 90). A mosaic of patches with different characteristic grasses, sheep’s fescue Festuca ovina, wavy hair grass Deschampsia flexuosa and common bent Agrostis tenuis for instance, among the dwarf shrub dominants, occurs on this dry heath as it does on the grasslands of the same map. It is in these patches and especially where they amalgamate into lawn-like areas that

FIG 90. Bristle bent covering the long slope of Rippon Tor with scattered western furze bushes.

rarities like the purple Vigur’s eyebright Euphrasia vigursii occur. Vigur’s is a likely stable hybrid among the semi-parasitic eyebrights and only grows in the southwest peninsula, Dartmoor is again a stronghold and Lydford High Down the citadel within it. The grassy elements of this heath are almost certainly more dominant now than they were in 1972. It is suggested by contemporary upland ecologists that too intense burning and the mixture of grazers after the burn – sheep, cattle and ponies as well as rabbits – keep the dwarf shrubs at bay for longer. Interestingly the toughness of bristle bent tufts in the face of fire seems to be reflected in their avoidance by grazing stock. It is important to register that, as well as the heathers, western furze is a senior member of the dwarf shrub community on this heath, and that combination is now what the ‘visionaries’ 30 years on call western heath.

Just as Ward blurred the boundary between blanket bog and heather moorland, so the 2005 Vision Group, taking its map and brief text together, blurs in a different way the boundary between heather moorland and western heath – a phrase neither Ward nor the NVC used. But no one should be surprised that grazed habitats evolve, even in 30 years. Everyone agrees that ling characterises heather moorland on Dartmoor, though all the dwarf shrubs and moorland grasses may be present. Bilberry Vaccinium myrtilis is quite common and cowberry Empetrum nigrum grows near the summit of Ryders Hill where it may well have grown 15,000 years ago. Western heath has all three heathers though bell heather is regarded as symbolic, but with more extensive areas of short-cropped grassland and with western furze almost as a distinctive companion. Where the dwarf shrubs are in clear domination, to the apparent exclusion of all else at a distance, and they flower, as they all do together suddenly in late summer, they create one of the most colourful and thus memorable communities of plants to be seen within the National Park (Fig. 92). This remarkable sudden colouring of patches on the middle altitude Dartmoor slopes, a dense mixture of bright yellow and magenta with variable shades of mauve and pink, provides a splendid context for the personal

FIG 92. The bright mixture of ling, bell heather and western furze in August alongside the road between Cold East Cross and Hemsworthy Gate.

harvesting of bilberries, either for consumption on the spot or retrieval for pie-making at home. There are extensive such stands on Trendlebeare Down, on Haytor Down, in the Rippon Tor newtake southwest of Haytor and on Wittaburrow and Buckland Common south of that, also on Buckfastleigh Moor, Penn Beacon and parts of Roborough and Plaster Downs, but hardly any on similar slopes in the northern moor. European gorse Ulex europeaus may also be present at the edges of these sites. It is the well-known leggy shrub characteristic of walls, hedge-banks and verges throughout the British Isles and can dominate such lines here on Dartmoor and spread from them to form extensive shrubberies in enclosures and on commons – Holne Moor’s northeastern corner is a classic example of that. It flowers all the year round (hence the traditional country saying, ‘when the gorse is not in flower kissing’s out of fashion’) but does have its own climax in April and May on Dartmoor when the heavy coconut-like scent intoxicates those getting out of the wind behind a good clump of it (Fig. 93).

The ‘western heath’ of 2005 then, in part picks up the 1972 map’s ‘heath’ and ‘grassland-with-gorse’. Some of the 1972 ‘heath’ is heather moorland in Vision terms – notably on Chagford Common and the adjacent parts of the Forest: Bush Down, Headland Warren and Coombe Down Common (Fig. 94).

Bracken

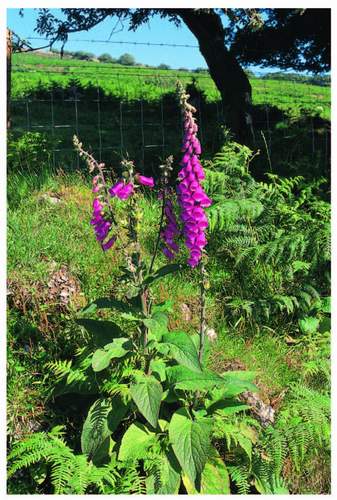

Bracken is part of the grassland and heath story, but its vigour, and thus its contribution to the landscape and effect on access alone warrant its own special treatment here. The bracken plant Pteridium aquilinum is a dense network of underground rhizome(s) that annually sends stalked and branched leafy shoots above ground often forming dense and extensive stands covering whole hillsides. In 1972 and 1994 bracken invasion warranted a special category even on the maps. Its spores, of course, have been present in the peat-protected record since 8,000 BP, or so, and at a fairly constant density from 3,500 BP to the present, with a slight increase during the Dark Ages. Intriguingly none of the eighteenth-century observers mention bracken, but Worth in 1933 and Harvey 20 years later thought it important enough to register. By the latter date its invasive tendency was attributed to the successful survival underground of the main plant in the swaling season – October to March. Its fronds show where it is alive when they protrude for annual reproductive purposes and to boost the energy of the whole clone with some opportunist photosynthesis from May to October. Bracken is also a choosy plant and not a bad indicator of a good depth of acid-to-neutral well-drained soil, as witness its ready take-over of once-cultivated ground given

the opportunity. Its mapped concentration at the outer edges of the whole moorland block and throughout the middle-eastern brown earth area demonstrates its rampant success in the right conditions (Fig. 95).

The Dartmoor Commoners’ Association in its submission to the Royal Commission on Common Land in 1956 suggested that bracken had begun to spread as commoners cut less and less for bedding – but many longstanding hill-farmers also pointed to a reduction in cattle grazing in their lifetime, and thus far less trampling in recent decades. When intense summer grazing was more the norm, heavier lowland cattle like South Devons were brought up, especially from the South Hams, and as many as three such herds would regularly work the lower western slopes of Hameldown where bracken is now dominant. Apart from spraying with Asulam, a commercial herbicide which kills the next year’s growing points below ground, crushing bracken at the ‘fiddle-head’ stage in early summer is the acknowledged best form of controlling it. Boulders hidden from the tractor driver’s eye by the bracken itself are an inhibition for both economic spraying and mechanical crushing attempted too late in the season. Aerial spraying is efficient and on the face of it well tailored to landscape sensitivities because its work is brief and the effect is not seen until next year and is then wholly positive. But it is expensive, hedged around with health and safety difficulties and unpopular in many quarters – those of principle and those protecting holiday-season wanderers among them (ideal timing is late July when the fronds are at fullest spread). The Vision commentary rightly points up bracken’s ecological value and thus its acceptability ‘in some places’, especially as habitat host to high brown fritillaries Argynnis adippe and much of the whinchat Saxicola rubetra population.

But it is universally accepted that bracken is, and always was, a problem plant. Some archaeologists believe it defeated high-level farmers in the late Middle Ages and that whole villages were abandoned because of it. In the twenty-first century as we have just seen, it hides boulders from ramblers, prehistoric remains from their seekers, fire-break making swipe operators and would-be sprayers of it, from itself. Its rhizomes are regarded by archaeologists as a damaging agent for the same remains. Its preference for particular soils and dryness means that scrub and woodland development are likely successors to it, especially adjacent to existing tree seed sources. Its spores are carcinogenic to mammals, among the few invertebrates it harbours are the ticks that transmit louping ill (Ovine Encephalomyelitis) to farm stock and birds, and it can wet you to the armpits as you try to get through it. The dead fronds smother other struggling vegetation and accumulate in dense beds except where swaling finds them. On the other hand it provides the summer shade necessary for bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta survival if the trees have gone (Fig. 96) and violets

FIG 96. Sheets of bluebells in the open in Okehampton Park.

Viola spp. for fritillaries (Fig. 97); and from November newly dead bracken provides one of Dartmoor’s richer colours when many other communities have become drab and before the ling/purple moor grass light and dark contrasts are as striking as they can be from mid-winter on, as Figure 95 showed.

The final moorland argument

‘Grassland invaded by bracken’ is one of the 1972 map’s three grassland categories (and by implication a fourth, courtesy of purple moor grass, might now be added) and they still form a useful concept. The acceptance that ling is present in all four and that grasses are always present in the heath means that there is no great conflict between the 1972 interpretation and the 2006 vision, with that of 1994 sitting comfortably on the fence. The simplification of the Vision’s map is understandable when one considers its original purpose and that the process of its achievement is almost more valuable than its expression on paper. About grassland – carefully labelled ‘acid’ – the Vision, which does not map it, expects it to be reduced in total area by 2030. It acknowledges, however, that extensive tracts of it must be retained for the conservation of a few rare plants: Vigur’s eyebright, and wax caps for instance, some insects, field grasshoppers Chorthippus spp., dor beetles Geotrupes stercorarius and hornet robber flies Asilus crabroniformis which prey on both. Ground nesting birds, especially lapwings Vanellus vanellus also need short-cropped grassland especially for feeding. Nevertheless western heath must, even if by default, include all that grassland and it would be a pity if it became interpreted in the future as a sort of Dartmoor ecological dustbin, attempting to contain too much and an easy way out of an identification dilemma.

The NVC needs to be referred to again. Purple moor grass tends to dominate the damper end of the grassland spectrum (M25) and bristle bent the drier (U3). Cotton grass will emphasise the former and heath bedstraw Galium saxatile the latter, but tormentil is present throughout that spectrum – taller with the purple moor grass and short and supine among the bristle bent tufts and in the short-cropped sward where its four bright yellow petals make it the star of that particular show. Near the dry end, and especially on the acid brown earths and simple podsols, a shorter turf mainly of sheep’s fescue Festuca ovina commonly occurs, common bent and sweet vernal grass Oenanthe odoratum, with heath bedstraw and tormentil always there (U4). It forms the common sheep pasture of Dartmoor’s eastern slopes and summits, but as we have seen a candidate for bracken invasion when only sheep are left to graze it.

So, Ward’s heath and four grasslands often form a mosaic in detail that the present visionaries wish to call western heath, and for ‘management-by-agreement’ purposes that may be perfectly practicable. As the last commentary on this particular discussion: when Ward extended his association analysis from the original ground transects by reference to the aerial photographs, the significance of a ninth vegetation type was underlined, and he called it grass-heath. ‘The stands appeared to be a fairly heterogeneous collection in terms of their physiognomy, but they did have in common the fact that they were all transitional between heath and grassland.’ Some were grass swards where isolated bushes of ling, western furze and bilberry still remained, while others had the three shrubs finely mixed with the grasses but with a very low percentage cover of each. Constant species are ling, tormentil and two mosses, but common bent, carnation and pill sedge Carex panicea and C. pilulifera, red fescue Festuca rubra, heath bedstraw and heath grass Sieglingia decumbens were common; and bristle bent, sheep’s fescue, purple moor grass, matt grass Nardus stricta and western furze occurred in more than half the samples. The whole list is reproduced just to emphasise the complexity of the stands. Ward says: ‘due to the extremely variable appearance of this vegetation, it would not have been possible to define suitable criteria by which to recognise it (presumably from the air). In practice such stands have been classed in either grassland, heath or grassland with gorse.’ It seems to say it all.

Valley bogs and mires

After that complexity, this last of the vegetation types of the open moorland has no such problems of recognition or classification. All are agreed that it normally expresses itself as a relatively narrow, linear pattern along valley floors and sometimes in more steeply graded downslope depressions often from the edge of the blanket bog. But as we have seen when discussing peat deposits there are notable examples of broader bogs in shallow, wide valley basins often when headwaters meet. Classic sites are Taw Marsh and Raybarrow Pool in the northeast of the northern plateau, Redlake near the head of the Erme, Foxtor Mire from which the Swincombe emerges. Its extent is seen in Figure 98 and it was the probable inspiration for ‘Grimpen Mire’ in The Hound of the Baskervilles – Conan Doyle stayed in Princetown while writing some of the story. Muddilake in Spaders Newtake draining to the Cherry Brook was seen in Figure 89. The two last named are within large enclosures, and of course there are long and narrow valley bogs among the more elderly and smaller enclosures of the middle-eastern valleys, especially along the East and West Webburn. Near the head of the latter at Challacombe (Fig. 99) the peat accumulation is such that the bog is raised in the strict sense of the term, there are others below Crockern Tor and above Statts Bridge, both close to the B3212. Even further east there are important valley mires at Blackslade, which is a Site of Special Scientific Interest southeast of Widecombe, and in Bagtor and Halshanger Newtakes either side of Rippon

FIG 98. Foxtor Mire sunlit in the middle distance. Whiteworks buildings can be seen beyond the mire on the right, with Nun’s Cross farmhouse further left. Fox Tor itself is on the extreme left.

Tor. The last named occupies a broad and shallow basin at the head of the River Ashburn and is easily overseen from Cold East Cross on the Widecombe to Ashburton road. It is pictured in Figure 16.

Valley bogs differ substantially from blanket bog because of their physical context whose significant effect is water movement. The water within a valley bog distributes chemical goodies for plants laterally throughout the site. Mineral material is continuously washed in from the valley sides and on to the bog surface however gentle and limited in height those slopes may be, providing nutrients denied to the plants on a summit blanket bog whose surface is sealed off from the underlying rock by thick peat.

FIG 100. Bog bean flowering in Challacombe bog; its trifoliate leaves in left foreground.

So, unsurprisingly, we have on these wet valley floors the richest flora available in one site within Dartmoor, indeed as acid mires go these are as good as they get in upland England. While the floristic colour combination may not compete for intensity with the August western furze-with-heathers of the heathy slopes, its variety and the mosaic of small patches within a polka-dot pattern of single flower-heads has its own charm. All the plants have both formations. Cotton grasses and bog asphodel are often in patches of white and yellow, but can equally punctuate the green base in an even scatter. Yellow marsh St John’s wort Hypericum elodes, the small white towers of bog bean Menianthes trifoliata, red rattle or marsh lousewort Pedicularis palustris and lesser spearwort Ranunculus flammula have similar distributive patterns. Wetter places, especially the arterial slow streams, have water crowfoot Ranunculus aquatilis and pondweeds Potamogetons; bare peaty muddy surfaces carry greater birdsfoot trefoil Lotus pedunculatus, marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle vulgaris, bog pimpernel Anagallis tenella, marsh bedstraw Galium palustre and marsh violet Viola palustris. Such surfaces also support pale butterwort Pinguicula lusitanica quite often (Fig. 101) and its grosser cousin P. grandiflora very rarely (there is a fair collection near East Bovey Head, while their fellow insectivores, round-leaved sundew and its narrow-or

FIG 101. Pale butterwort in surface scrape.

oblong-leaved cousin D. intermedia, may prefer closer association with mosses. Sphagnum species are everywhere, often forming tussocks which higher plants pierce from below. Rushes are similarly widespread and their tussocks may bear one’s weight – early and late in the season they appear to dominate whole bog surfaces, and in some cases they really do, but they do the same in very wet meadows. Tall, magenta ragged robin Lychnis flos-cuculi early and shorter, blue devil’s bit scabious Succisa pratensis late, are mire-edge plants and splendid less common flowers will sometimes leap out at the sharp observer from that edge, southern marsh orchid Dactylorhiza praetermissa (Fig. 102) and ivy-leaved bellflower Wahlenbergia hederacea among them. In one place in western Dartmoor drooping Irish lady’s tresses Spiranthes romanzoffiana hangs on by the skin of its teeth, in the face of unfettered grazing.

The Vision map draws attention to the fact that ‘all mires are not shown’ but that all ‘internationally important’ ones will be retained and managed by grazing, while 10 per cent will be allowed to ‘scrub up’ into willow and alder in the first

FIG 102. Southern marsh orchid near Cator.

instance. The cartogrammetric nature of the Vision map means that the representation of a habitat as finely drawn in reality as long, narrow valley bogs, cannot be expected to be very accurate. Ward, as we have seen, was criticised for over-playing the valley bog network. Despite both these commentaries, valley mires extend into the enclosed landscape, often close to roads, a flavour of precious wildness among fields that is quintessentially lower Dartmoor.

THE ENCLOSED LANDSCAPE

The valley bogs and mires clearly straddle the boundary, and the distinction, between open moorland and total enclosure and ease the transition into our second vegetation suite in their own right. Because they are often bordered by damp pastures of purple moor grass and rushes whose Welsh name ‘rhos’ has been adopted even by European convention (Devon, Wales and Eire have more of it than the rest of Europe together) their influence for us is widened. Such wet fields penetrate a complex pattern of fields and walls, lanes and hedge-banks, which landscape embroidery contains knots of buildings ranging from single farmsteads to full-blown villages. Isolated single buildings do occur but not as in the consistent pattern of the field barns of the Yorkshire Dales.

There are, in this landscape, two types of enclosure to consider. Large, walled spaces called newtakes sprawl across the central basin of Dartmoor closely associated with the two turnpikes – Moretonhampstead to Tavistock and Ashburton to Princetown and on to Yelverton and Plymouth, mostly ‘taken’ from the Forest in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by authority of the Duchy of Cornwall, Muddilake in Figure 89 is in one. There are also odd ones at the outer edges of the original moorland north and east of Widecombe and up the west side from Merrivale to Sourton, largely as a result of successful applications under the Enclosure Acts. Most of these later newtakes still consist of ‘moorland’ or at least grass moor and dwarf shrub communities even though some were occasionally and patchily limed up to the mid-twentieth century. An exclusive enclosure of moorland for those still having suckler cattle herds is very valuable. ‘That’s my hay’, said one knowing farmer explaining to the innocent what newtakes were for. He let it grow all summer and put his hardy hill cattle from the common into it for the winter. Another worked out how much winter ling equalled a bale of hay, and the trace elements that the ling contained which were not available from his hay meadow.

But newtakes have a longer history. Sometime between Domesday Book (for there is no reference to them there) and the late fourteenth century, the administrators of the Forest encouraged the establishment of farms within it, probably to ensure that controlled grazing maintained some open land for the Forest’s prime purpose – hunting (remember the Mesolithic hunter/manager!). It also meant that there was a labour force readily available on the spot for all those tasks that were ancillary to that purpose. The farms established then are still known as the ‘Ancient Tenements’ and are not all separate holdings, or holdings at all now. They are crowded together, but in two blocks north and south of Riddon Ridge at the centre of the eastern edge of the Forest. They were thus an extension westward and upward of the Saxon pattern of farms and commons already well established in the vales of the Dart catchment. The southern block lies between Prince Hall and Huccaby in the south and up to Riddon on the Wallabrook; the northern block stretches from Bellver to Walna, whose remains are near the Warren House Inn, in the north, with an outlier at Postbridge called Hartland (see more detail about them in Chapter 7). The tenants of these farms were allowed to enclose land in about 3.25-ha plots according to certain rules, one of which was the speed with which the enclosure could be completed. The result is that these more elderly smaller newtakes often do not have right-angle corners – it was quicker to keep building the dry-stone wall on a curve. Many have been subdivided at later times, often when original single farmsteads became hamlets of three or four smallholdings and good fields were shared between them. Thus right angles may have re-entered the pattern at that time although the curved boundaries are still obvious on the maps of farms like Babeny and Hexworthy. These smaller but still high-level fields are usually no longer heathy. Most are permanent grass that has been limed and the driest have become hay meadows, ‘shut up’ from March or April to July.

In parallel with the Duchy, perhaps much earlier in some cases, Saxon or Norman lords of the manor also allowed, even encouraged, the creation of farmsteads in the waste-of-the-manor. Holne Moor’s 4,000-year spread of enclosure remains has already been registered as incorporating prehistoric, Saxon and mediaeval patterns, some seen in Figure 75, but at the northeastern edge of the present common are a string of farms – West Stoke, Seale’s Stoke, Middle Stoke and Fore Stoke. The Stoke element implies an Anglo-Saxon stock farm with a dwelling and such places were often set up as ancillary holdings to a main farmstead in good economic times. Their fields are thus of great age, and their pattern is physically extended by the observable remains of banks out on the common although the present outer boundary is undoubtedly a ‘cornditch’ against the common. They are 300 m above sea level, small and with sheltering walls and banks which offer yet another habitat possibility or variation on the high meadow theme. Similar small fields reach 400 m at the Merripit farms once a single Ancient Tenement northeast of Postbridge.

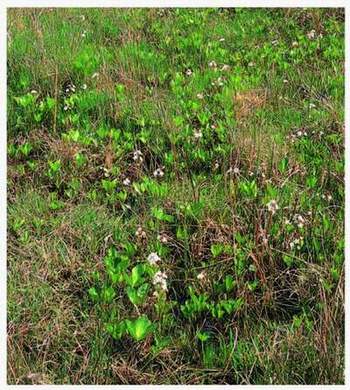

As Vancouver noted all these fields played their part in a mixed – once self-sufficient – local farming system. They may well have been ploughed, re-seeded, limed and manured many times in their 1,000-year-plus lives. Their twenty-first-century biodiversity depends almost certainly on how long it is since the last time their surface was broken or enriched, in farming terms. Management agreements have been made with the occupiers of many of them – initially by the NPA in the 1980s, and continued under Environmentally Sensitive Area schemes by MAFF and then DEFRA – which is some commentary on their contemporary richness and biodiversity value (Fig. 103). Meadow and bulbous buttercups Ranunculus arvensis and R. bulbosus, black knapweed Centaurea nigra, self heal Prunella vulgaris, spear thistle Cirsium vulgare and creeping thistle C. arvense, sheeps bit Jasione montana in drier parts and devil’s bit scabious Succisa pratensis in lower-lying fields and in the damper corners, yellow rattle Rhianthus minor and greater butterfly orchid Platanthera chlorantha (Fig. 104), along with the grasses: sweet vernal Anthoxanthum odorata, crested dogstail Cynosurus cristatus, common bent Agrostis tenuis, cocksfoot Dactylis glomeratus, red fescue and Yorkshire fog Holcus lanatus all tell of that richness on the ground.

Apart from these select flower-rich hay meadows and the best of the rhos pastures, within the enclosed landscape it is the roadside verges and the unmetalled wider driftways that offer the only other open feral habitats not being heath or moor.

Driftways are winding avenues between fields for stock to be driven from farmyards and linhays to the open common and back (Fig. 105). Decent lengths of continuous verge are really confined to the turnpikes – the ‘scissor roads’ B3212 and B3557, and the A382 and the A386 – and although historically young, at least they can be dated and represent an unequivocally unlimed, un-fertilised and largely unmanured sample of permanent grassland. Otherwise there are little beads of verge on the more important inter-village lanes of the middle east and more importantly the outer edges of those driftways. The latter have been well manured during their long history as frequent nettle beds proclaim, but their soil remains neutral to acid and they have certainly never been ploughed.

FIG 105. Field pattern on the east flank of Cosdon. Two driftways intersect the fields, both emerging on to the common at the left-hand side of the block.

FIG 106. Devon bank with the bluebell, stitchwort, red campion combination that follows the primroses. Some lesser celandines linger at the bank foot.

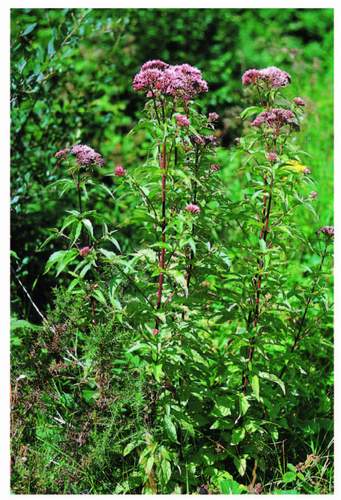

In these open linear sites the early bright yellows of lesser celandine Ranunculus ficaria and paler primrose Primula vulgaris are followed by the patchy but patriotic red, white and blue of campion Silene dioica, stitchwort Stellaria holostea and bluebell, the latter usually indicating the shade of bracken to come (Fig. 106). Early purple orchids Orchis mascula punctuate these generalities in many places as does betony Betonica officinalis later on. As spring progresses a white floral domination develops as stitchwort is joined by cow parsley Anthriscus sylvestris, upright bedstraw Galium mollugo and ox-eye daisy Chrysanthemum leucanthemum, which then give way to the summery cream of hogweed Heraclium sphondylium and meadowsweet Filipendula ulmaria. Yellow reappears strongly in June and the scatter of hawkbits Leontodon spp., hawkweeds Hieracium spp., cat’s ears Hypochoeris spp. and hawk’s beards Crepis spp. persists until September, having been joined by tansy Chrysanthemum vulgare in mid-August, and in the shorter grass under the highway authority’s flail there are always dandelions Taraxacum officinale. Foxgloves Digitalis purpurea (Fig. 107) leap up and over-top all else in July on many a verge and willowherb Chamaenarion angustifolium and hemp agrimony Eupatorium cannabinum continue the pink-to-puce theme well into August (Fig. 108).

FIG 108. Hemp agrimony often dominates the August banks.

These last three creep up from the verges wherever proper Devon banks give a toehold. Better drainage and slight leaching may be the motivator, but the foxglove seed bank must be full and of long standing, for when a bank or wall is rebuilt they are always the first big plants to appear in the new crevices. These banks, in the Dartmoor lower landscape all round the high moor, are of course a habitat in themselves, as may be the double-skinned dry-stone wall variation which often supersedes them up the granite slope. Most of the plants listed for verges just now cling also to them and find their special niches. Lesser celandine likes the damper base, primroses like to be up away from the road edge and foxgloves, when their turn comes, prefer the top.

Devon banks are vast structures, a late-eighteenth-century recipe says that they should be 9 ft (2.75 m) across at the base and 4 ft (1.22 m) across the top and stand 7 ft (2.1 m) high, then be stoned to 4 ft (1.22 m) high on either side. They were to be topped with cuttings and seedlings of a large number of shrubs and trees at a specified number per unit-length. Off Dartmoor their origin almost certainly lies in the lack of good stone for wall building in Anglo-Saxon times except in odd places where limestone or schist outcropped (Torbay and

FIG 109. Dartmoor hybrid between South Devon bank and granite dry-stone wall at Welstor above Ashburton. Beech has been planted on the crest.

FIG 110. The significance of hedgerow trees in the farmland downstream from Widecombe.

Plymouth hinterlands, patchily from Chudleigh southwest to Buckfastleigh and between Start and Bolt Tail) and no formal hedging tradition. The only precedent was the low earth banks separating strips in the open field. If you ‘suddenly’ needed to contain stock or keep it out, why not simply enlarge the low bank. There is also the suggestion that adjacent landowners, or in the Dark Ages probably long-leaseholders, digging a boundary ditch between them side-by-side, throwing the earth and stone out on their own side, created by chance a strip of no-man’s-land between crude banks. The strip became a passage and then a hollow lane whose bottom became rich enough over time from the passage of cattle to warrant digging out and spreading on the fields, thus increasing the hollow characteristic. Such banks and their attendant lanes creep up into the National Park, but there, as we have seen, the abundance of granite boulders at the surface must have made wall building a logical alternative which the prolific prehistoric precedents demonstrated to the Anglo-Saxon settler. Banks and walls both provide important, well-drained sites for plants and animals as variations on the open verge. Banks particularly provide good footholds, while walls have their own specialists – wall pennywort and ivy-leaved toadflax on the sides and more than one stonecrop species on the top, hard fern and harts tongue providing a shiny green accompaniment often from the base of the wall or halfway up the bank on the shady side (Fig. 109). Both wall and bank happen to support trees, the Dartmoor version of the hedgerow tree of lowland landscapes, and they give as particular a character to the fringe farming landscape here as they do to the Vale of Pewsey or the Weald (Fig. 110).

DARTMOOR’S WOODLAND

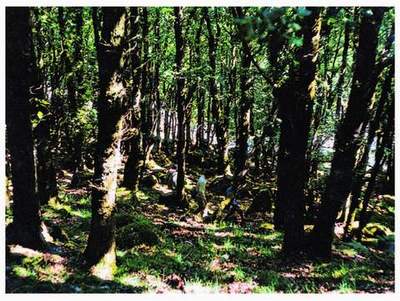

The single tree is one thing, the wood quite another. The word ‘dart’, as Chapter 1 hinted, is a derivative of the British ‘daerwint’ (and ‘derw’ is oak), and means oak tree river in the Celtic languages that almost always gave the British landscape its original names for physical features. The River Dart’s valley sides from Dartmouth to Totnes and from Buckfast into Dartmoor as far as Dartmeet are clothed in oakwoods still. Much further into the moor is a small oak copse, Wistman’s Wood (Fig. 111), well up the West Dart above Two Bridges. It has two analogues, Piles Copse above Harford on the Erme and Black-a-Tor Beare on the West Okement that, reaching 450 m OD, is the highest broad-leaved wood in the national park. We shall consider them at greater length in due time. But it seems somewhat ironic that the first element of the name of this great hill is about woodland which covered most of it before man intervened, rather than the moorland of the second element which man now reveres for its relative rarity in

FIG 112. Looking up the East Dart valley, Brimpts Farm is at the top of the left-hand middle-ground, with plantation still surrounding fields.

the southern part of this island and the scope it offers to him for recreation in all its forms. That irony apart, the whole of contemporary Dartmoor’s tree cover falls first into two equal parts by area: long-established deciduous woods, which will complete and dominate this account, and new-ish conifer plantations.

Coniferous plantings

The creation of plantations on hitherto open moorland newtakes was begun by Duchy of Cornwall leaseholders near the end of the eighteenth century at Beardown, Prince Hall and Tor Royal – none were then very successful, but at Beardown and Tor Royal the idea, at least, persisted and a plantation still sits at the former and a shelter belt along a third of the length of the road from Tor Royal to Whiteworks. But, developing a story begun in Chapter 1, from 1862 onwards at Brimpts above Dartmeet the Duchy’s land steward who happened to live there, planted 40,000 trees (Fig. 112). The first crop was felled early, and transferred to Princetown by aerial ropeway, because of the demand generated by the First World War. That seems to have inspired the then Duke (later briefly Edward VIII) to investigate the potential of other newtakes with the fledgling Forestry Commission after that war. He began the planting but eventually leased land at Brimpts, Beardown, Fernworthy and Belliever to the Commission, which completed the largest and highest plantations we still see (Fernworthy’s western edge reaches 500 m and sadly, in scenic terms, over-tops the skyline from Postbridge and other parts west). Soussons Farm, across the road from Fernworthy and only a mile from Bellever, was added to the Commission’s estate at the end of the Second World War, bringing the total area to 1,500 ha. All these separate blocks are currently going through their first harvest, providing, however temporarily, a new set of habitats as clearings, and scope for enterprising species like nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus and grasshopper warbler Locustella naevia to linger and breed. After its early habit the Commission created smallholdings at Bellever and the retained Soussons, for the retention of part-time forest workers who farmed for themselves in their own time. At Bellever houses were also built to house foresters and woodmen.

Four other plantations of varying size but on high-level moorland and adjacent fields were created in this same time span. Plymouth City Council planted the biggest – 280 ha of high-level fields in the closer catchment of its Burrator Reservoir – soon after the First World War. Convicts planted, first, northwest of Princetown around the prison quarry and on both sides of the Princetown-Rundlestone Road. Then a little later they created Long Plantation, well north of the prison, from the B3357 to the southern boundary of the military Merrivale Range to provide shelter from the northeast for the most exposed part of the Prison Farm. (Exposure can be a problem for the plantings themselves, as Chapter 6 will tell.) Finally, a southwestern newtake, Hawns and Dendles Waste, occupying a ridge between the River Yealm and Broadall Lake, was planted in the 1950s.

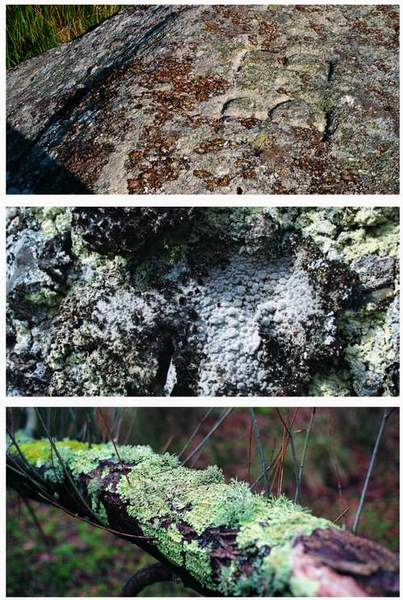

These four have been more significant for their presence in the landscape than for any internal, intrinsic value. Burrator, apart from Brimpts, the oldest of these conifer woods, makes the central Meavy valley as it leaves the moor proper, a discrete ‘lake-in-forest’ vignette. Despite that unity from within it is, from anywhere outside, in huge contrast with the moorland above and around it and with the fields and broad-leaved woods of Sheepstor and Meavy parishes immediately downstream of the reservoir’s dam. Nevertheless, good management of the Burrator woods over some 80 years now has produced a very reasonable density of stems and enough light reaches the forest floor to maintain a green lawn of a grass/moss mixture that walkers and trespassing sheep enjoy in about equal parts. The many walls remaining from the predecessor fields within the forest now bear a dense crop of mosses and scattered ferns varying with the aspect of the wall side and light penetration. Lanes, for instance, with two walls, create a wider slot in the canopy. The popularity of the site with very local and Plymouth-based visitors has led to much effort to provide clearings and sustain broad-leaved trees as well as many parking places, walking, riding and cycling routes, sometimes utilising the Devonport Leat side and the bed of the Plymouth to Princetown railway, both of which pass through the forest.

The Hawns and Dendles Waste ridge is lower than those to east and west of it so no ‘wider landscape’ problem really attached to its site. Nevertheless its planting, by private investors, was far from popular with moorland protectors if only because of its intrusion into the southern plateau, as any map shows. In the last decade of the twentieth century it was bought, after clear-felling, by the NPA which spent much energy – and cash – clearing stumps and brash so that moorland could re-develop on an uncluttered soil surface. The prison plantings are strictly functional in origin, Long Plantation strangely complements Beardown when one is between them in the Cowsic valley, but there is tangible relief for the walker on emerging upstream from that skyline ‘avenue’. The Princetown sheltering woods took a greater beating than others in the great storm of 25 January 1990 and their replacement includes a much higher percentage of broad-leaved trees.

All this had been paralleled within the enclosed landscape by smaller conifer plantings notably above Ashburton on Ausewell Common, at adjacent Buckland, up the Webburn valleys and further north at Frenchbeer – another Duchy holding – quite early (Fig. 113). Torquay Urban District Council planted much of the small catchment of its Tottiford reservoir complex (in the far east) in the

FIG 113. Conifers inserted into an oakwood landscape – here on a spur between the Webburn and Ruddycleave Water.

early 1930s. Later, Kingswood and Dean Wood west and southwest of Buckfastleigh were converted to conifers and from the end of the 1920s so was the woodland of the middle Teign valley. The Dartington Hall trustees, whose inspired benevolent despot Leonard Elmhirst had rural economic regeneration ambitions for South Devon which included afforestation and sawmilling, purchased nearly three miles (4.8 km) of the right-bank valley side. It was clear felled and planted with Sitka and Norway spruce, Douglas fir and European larch and a sawmill built at Moretonhampstead, where Elmhirst’s planters and woodmen still lived in the late twentieth century. Smaller plantations were developed in the upper West Webburn valley around Heathercombe, on the eastern flank of Easdon and in the Wray valley at Steward and Sanduck Woods around the same time. In the last case the woods on the western valley side adjoining the railway line had been felled in both World Wars because of the ease with which the timber could be taken away. Dartington stepped in here too and planted some hectares of larch and Douglas fir after 1945. Sanduck Wood now belongs to the NPA along with neighbouring broad-leaved woods.

It is important in the contexts of both biodiversity ambition and landscape change to note that this addition of the first new and very visible habitat to the Dartmoor suite for perhaps 2,000 years took only 200 years to run its course. It started when only a few conifer species were available – Scots pine, European larch and Norway spruce – which were often at the outset mixed with oak, beech and sycamore. Only after the First World War were the western hemisphere Douglas fir, very far eastern Sitka spruce, and Japanese larch brought to the high Dartmoor plantations. But it was their positioning in the scene, apparent obliteration of ancient monuments and finally coincidence with national park designation, that roused so much opposition that new planting extending the area of coniferous cover on the high moor is no longer contemplated. In one case just mentioned – Hawns and Dendles – wholesale removal of a living eyesore (to moorland devotees) has happened at public expense but with the Heritage Lottery Fund playing a considerable part in the exercise.

Broad-leaved woodland

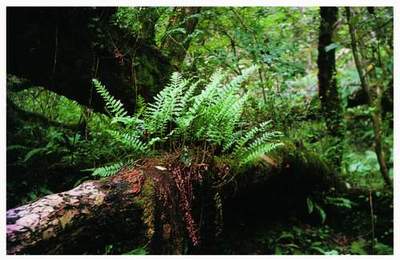

It will be necessary to return to the plantation as animal habitat, but the other half (2,000 ha) of the Dartmoor National Park’s woodland must first be described. There are essentially four types of broad-leaved wooded landscape within the park: valley-side woods, parkland, wet woodland and orchards. By far the most extensive is the first of those, the old original valley-side successor-without-a-break remnant of the pre-Bronze Age forest. The gorge sections of the Dart and the Teign carry the longest stretches, but the Bovey, the Wray, the Ashburn, the Erme, the Yealm, the Plym and the Meavy, the Walkham, the Tavy, the Lyd and both Okements all bear their share. All carry oakwood dominated by the sessile oak Quercus petrea, but with some English oak Q. robur and their hybrids present, a sprinkling of ash, beech and sycamore and a thin under-storey of hazel, rowan and holly, often localised and sometimes absent over substantial areas within any particularly extensive wood. Not only are these woods in loco filii to their postglacial predecessors on sites which have never seen anything but a tree cover, but they are classic British upland oakwoods, albeit with a southwestern and oceanic gloss. In most valleys they straddle the granite/metamorphic-aureole boundary with good lengths on both sets of rock, and the character of the woodland floor varies markedly on each side of the line if only because of the boulder density on the granite side. Within this woodland type must of course be those three high-level oak copses already listed and deserving their own treatment, but each does occupy a low-valley-side slope or narrow valley floor against the stream.

Parkland

There are places where the lower-level valley woods merge with, or abut, the second broad-leaved woodland type – the parks, where man’s more recent but still historic hand is visible, where, at the extreme, scattered venerable trees punctuate a grazed grassland, as in Okehampton Deer Park, Whiddon Deer Park near Castle Drogo, Blatchford near Cornwood, Woodtown near Sampford Spiney, Holne Park and Parke at Bovey Tracey (Fig. 114). But more often 200-year-old estate management of the otherwise ancient semi-natural woods is recognised by the insertion of specimens and groups of larch, more beech, even some sweet chestnut (for estate fencing) into the oak-dominated woodland context. Such management has also tolerated the rarity or the idiosyncratic. In Holne Chase, a 200 ha domed wood in the biggest meander of the Double Dart, small-leaved lime and wild service trees occur, the former in a large pure stand (Fig. 115).

FIG 114. The National Trust parkland at Parke takes centre stage in the landscape between Bovey Tracey and Haytor Down (on the skyline). Parke House, pale grey and at the right-hand end of the park in this picture, is the headquarters of the National Park Authority.

FIG 115. Holne Chase – 200 ha of oakwood filling the huge meander of the Double Dart – seen from Buckland Beacon. The southern plateau forms the skyline.

Wet woodland (carr)

Both valley-side ancient oakwood and parkland may join with, or contain, the third broad-leaved tree habitat and addition to the scene – wet woodland. Avenues of willows and alders can mark low-gradient stream sides wherever there is room in the valley bottom. Low groves of willow can develop in and around valley mires and in the valleys of the middle east are some of the most extensive and richest with good epiphytic beard lichens Usnea spp. and tree lungwort Lobaria pulmonaria, all proclaiming cleaner air. Goat and grey willow Salix caprea and S. cinerea respectively, with some alder Alnus glutinosa, provide the main canopy and clumps of marsh marigold Caltha palustris may vie with tussock sedge Carex paniculata in the eye-catching stakes. Throughout the enclosed landscape tiny wet plots of woodland recur as though ignored for centuries since alder and willow provided clogs, broom heads and basket materials. Remote from the wooded valleys, very small groups of willow appear high on the moorland, especially around old mineral workings where men manipulated water channels, often increasing their density on the ground adding leats to streams, and in abandonment leaving a happy site for all life that

regards water as a breeding ground, a refuge or just critical to good rooting and feeding. At the highest level, 535 m OD, upstream of Bleak House on the Rattlebrook for instance, the distinctive ferns, horsetails Equisetum spp. thrive in such a site and at the opposite end of the height spectrum the royal fern Osmunda regalis is not uncommon in the miry woodland alongside the Double Dart at 90 m or so.

Single trees and orchards

Isolated willow bushes at high levels punctuate wilder landscapes and encourage reed buntings for instance to hang around, even breed, and despite its sub-title this section would be less than adequate if it didn’t repeat the reference to the significance of the single tree separated from its peers in ‘Enclosed landscapes’ above. The willow example is often remote from other trees or scrub, but those not far apart, in hedges, on banks and in parkland provide important habitats in their own right and contribute greatly to the scene, especially in wider valleys such as the upper East Webburn. The most formal of sites in this connection is the fourth woodland type, the orchard, and there are still some 460 of them within the national park though only 10 per cent of those are currently managed. Map analysis suggests that maybe 300

orchards have been grubbed up in the last 50 years. Like other collections of ‘separated trees’ they offer different opportunities for a range of organisms from lichens to mistletoe and goldfinches.

Valley oakwood variations

Returning to the main body of the national park’s woodland and given the apparent uniformity of the tree species distribution across the spectrum of the downstream valley woods it is variations in the age of stems and more especially in the nature of the woodland floor that give different woods different characters. The former arises for three reasons. Estate planting was of its fashionable age – eighteenth into early nineteenth century – when Evelyn’s work and the ideas of Capability Brown penetrated this far west, and many woods not now seen to be parts of estates were clearly so when a species check is carried out. Thus the age of the trees planted and cared for then may well give us our oldest standing stems. Secondly, the two World Wars generated a demand for timber which took its toll of woods with the easiest extraction access in the first half of the last century and the unaided and largely unmanaged re-growth gives us a canopy now between 60 and 80 years old. But the third, and by far the most widespread, influence on even contemporary appearances is the fact that over centuries and up to the 1930s, the prime function of these woods was to provide, first bark for tanning and second the rest of the tree (useless without bark) for charcoal and domestic firewood. Up to and into the twentieth century, every market town had its tannery and there was a guaranteed and steady demand for oak bark for each one. Dartmoor is ringed by markets, in the classic exchange-between-two-economies siting. Store cattle and lambs, wool and metal ores came one way; fruit and wine, cloth, tools, flour and leather went the other. So the woods of the Dart, the Bovey and the Teign provided bark for Bovey Tracey, Ashburton and Buckfastleigh and almost certainly Newton Abbot, the Okements for Okehampton, the Tavy for Tavistock and so on. Charcoal, in a coal-less county, was also in similar demand for the knap mills and forges that turned out the edge tools and horseshoes which every part of the quasi-industrial sector of each town and even some villages had to have. Dartmoor farmers and miners in their turn needed leather and wrought iron and were glad to provide the raw materials for their production.