CHAPTER 5

The Dartmoor Fauna in the

Twenty-First Century

It is true that many moors are dominated by one or two, or even a single species of plant, and this inevitably restricts the numbers and diversity of animals in the community…But the resident animals, interesting in themselves, are reinforced by others of widely ranging habits which cross or visit the moors.

L. A. Harvey, Dartmoor, 1953

Professor Harvey’s discipline was zoology and while his authorship of the first New Naturalist volume about Dartmoor (from which this quotation is taken) demonstrated his impressive status as a rounded naturalist and Dartmoor devotee, his commentaries on the fauna of the 1950s must carry even more weight. He also readily acknowledges the aid he received in observation terms from well-known local mammal men of the day like H. G. Hurrell and all-rounders like Malcolm Spooner and his wife Molly. While he makes no generalisation about the other divisions of the landscape portrayed in this book’s previous chapter as he does for the moorland quoted above, he spends enough time on the woodland fauna, especially the birds, to show how rich that collection of habitats is compared with the wide open spaces. His references to farmland are thin but he was deliberately concentrating, as most writers did then, on what was, quite properly, perceived as the individuality of Dartmoor – its moorland and remnant woods. It is certainly the case that the valley, and the National Park fringe, farmscape is less individual as a set of animal habitats when compared with the land abutting the Park and to that extent will take up only the space here that its unique structural features and their denizens justify. This book, nevertheless, is about the whole rural space that is the modern National Park in which all units of the landscape have a place, a scenic and ecological role to play and thus a fauna to be accounted for – man within it.

That of course sets its own challenge. How comprehensive can such a description be? The total species list for a 953 sq km-space in any part of the English countryside, if known, would fill a bigger book than this. What assumptions, therefore, must be made? About selection; about significance; about the proper contribution made by any one animal community to the immediate ecosystem in which it sits and to the wider ecosystem that encompasses that?

That last is part of the methodological answer to the challenge. The community is more important than the individual. Its ecosystem – that which provides it with a home, a range and many living relationships – may be revealed to us as a significant component of a whole habitat. The habitat is itself a distinctive contributor to our perception of the place where we are standing in the Dartmoor landscape. Some characteristics of that animal community may hit us in the face, others will appear as we silently stand; but we may have to sit or kneel and scratch about to put more of the jigsaw together. So, we will proceed on the basis that the last chapter gave us the structural frameworks for Dartmoor animal habitats; and that there is still a ‘pyramid of numbers’, or at least of volume in biomass terms. Like Davis’s age-old geomorphological truth, that pyramid is an ecologically old-fashioned but an unashamedly useful way of organising our thinking about any ecosystem. In that pyramid, plants provide the huge ground floor, the grazers or vegetarians the very large first floor and their controlling carnivores and omnivores the next. The top carnivores deal with them, and they are joined by top omnivores (because we have to count ourselves in the grand ecosystem) who affect all of the layers, both occupying the peak of the pyramid. Then we have a formula for looking at the animals of Dartmoor with due economy but not missing anything that matters in these days of local, national and international biodiversity policy and its action plans.

As with plants, what matters to many in that context is, of course, any distinctively Dartmoor species, and especially those rare in both the local and the national scenes. Rarity, as a measure of effort to be expended by the conservator, can be a worrying concept especially at the edge of an animal’s range. What is rarity when applied near the south coast of an offshore island, if the species involved, say red-backed shrike or Cetti’s warbler, is common across the strip of water separating that island from the mainland? Perhaps, if science really does consist simply of physics and stamp collecting, rarity is only the proper interest

FIG 127. (above left) High brown fritillary; (above right) caterpillar depends on violets and thus bracken and pony trampling. (C. Tyler)

of the collector. But biodiversity, in the quasi-political sense at least, must encompass the rare, and the welfare of the rare may well become an indicator of success or otherwise in a nature conservation world. There is also much to be said for the premise that if conditions continue to favour the rarity, they are likely to be favourable for all its natural companions too, though beware innocent habitat management moves that have not calculated every potential consequence in advance. If the predators of ground-nesting birds’ chicks are also controlling baby rabbit numbers the conservator may have a dilemma to resolve about the structure of the habitat, if resolvable it is.

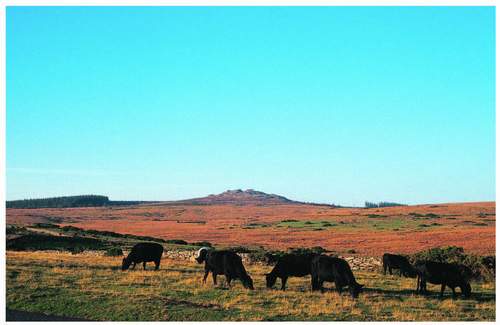

All this is important before attempting the faunal overview of Dartmoor in the twenty-first century because in this landscape man’s touch on the moorland, since its Bronze Age creation, has been of the lightest in the whole spectrum of agricultural activity. That touch still maintains what is to many the habitat framework that personifies Dartmoor – the complex that is the whole moorland – and therefore man and his animals must be included in the Dartmoor pyramid of numbers and in the analysis of the gross ecosystem. The habitat for the high brown fritillary Argynnis adippe may be an accident as far as the grazing motive of the hill-farmer is concerned, but their (farmer and motive) relationship may be a key factor in sustaining that population of butterflies among the sheep, cattle and ponies and the rest of the resident wildlife (Fig. 127). The number of cowpats determines the numbers of beetles that are key components of the diet of foxes, starlings and kestrels at particular times of the year. The scrape of a pony’s hoof at the edge of a mire gives a pale butterwort seed a chance it might not otherwise get and there will lie the fate of many an insect – the wool of a Scotch Blackfaced ewe on a rubbing rock can end up as readily in a wheatear’s nest as in that of a raven.

THE MOORLAND ANIMALS

The grazers or biters of heather occupy a huge range. It runs from tiny heather beetle larvae Lochmaea suturalis, through red grouse and lambs in spring, cattle in any winter, to ponies in hard winters when heather pokes through the snow while grass lies under it. Within that spectrum are more spectacular beasts like emperor moths and their caterpillars. The emperor moth Saturnia pavonia is somehow the symbolic insect of heather moorland, the caterpillars start out small, black and orange but develop into large bright-green animals with black rings bearing orange knobs both warty and bristly. Its parents are also large for open country moths, having fawn-grey wings with large dark ‘eyes’ on both pairs, though the male’s underwing may be largely orange, as may the tips of its forewings (Fig. 128). Male emperor moths fly by day and rapidly, and that is how they are commonly seen in mid-summer. They can detect a female’s ‘scent’ or pheromone up to 2 km away, but the females in their turn are not very strong fliers and are more active at night. Despite the bright colours of the caterpillar and the size and striking patterns of the adults, neither is seen easily at rest and the caterpillar inevitably skulks low in the heather for fear especially of cuckoos Cuculus canorus for whom caterpillars are a favourite food in the time off from parasitising meadow pipits

FIG 128. Emperor moths mating. (C. Tyler)

Anthus pratensis. Professor Harvey’s description of the emperor moth’s cocoon is worth quoting for its own sake but also as a sample of his own writing:

the cocoon is spun in the cover beneath the heather tops, and is an elaborate affair of closely woven brown silk and incorporating bits of heather twig and leaf. One end is left open for the emergence of the imago, but the opening is guarded by a cheval de frise of stiff silken points which converge outwards to form a conical valve easily enough pushed aside from the interior but firmly closed to intruders from the outside.

The gingery brown fox moth Macrothylacia rubi is more common than the emperor, but smaller, less patterned (though with two pale stripes parallel with the trailing edge of the wing at rest) and thus less conspicuous than its close cousin, the slightly larger oak eggar Lasiocampa quercus. The larvae of both feed on heather but the latter ranges more widely and its ‘woolly’ size means that it is often seen crossing paths with a humping gait at a fair speed. The larvae of a number of micro-moths live on grass stems, biting them near ground level and living their larval lives in tunnels in basal tussocks. The grass moths Crambus pratella and Caleptris pinella are common, the latter quite liking cotton grass as

well as the real grasses around it. The caterpillars of a number of butterflies are also grass feeders on the moorland, meadow brown Maniola jurtina, hedge brown (or gatekeeper) Pyronia tithonus and small heath Coenonympha pamphilus are commonest. Marsh fritillary Eurodryas aurinia caterpillars feeding colonially on devil’s bit scabious, in and at the edges of damper sites, represent one of the species most threatened nationally and for which Dartmoor is one of the few remaining happy places (Fig. 130) The narrow-bordered bee hawk moth Hemaris tityus is in a similarly precarious position in the same sites and intriguingly its larvae also feed on devil’s bit scabious (Fig. 131). Have we a race to the finish here? Two butterflies which do not yet cause alarm in biodiversity camps are the grayling Hipparchia semele and the green hairstreak Callophrys rubi both of which prefer drier ground (Fig. 132), the latter especially favours those carrying bilberry stands; perhaps their status and their preferences are connected.

FIG 131. (above left) Narrow-bordered bee hawk moth; (above right) caterpillar feeds on devil’s bit scabious and thus potentially competes with marsh fritillary caterpillars. (C. Tyler)

FIG 132. Green hairstreak, enjoys bilberry stands on drier slopes. (C. Tyler)

The most significant other insect biter of heather after the emperor moth caterpillar is the tiny grub of the heather beetle. Recent experience suggests that there are population explosions of heather beetles the causes of which are not yet entirely clear. A high infestation of the larvae shows itself first by its effect on heather plants in early to mid-summer, the fronds appear to turn wholly to a rusty orange-brown colour, though careful examination will reveal some green still evident close to main stems. When widespread, as it was on Dartmoor in 2006 and again in 2008, the rusty colour is seen to be concentrated along road and path sides and round the edges of mature heather stands where they are adjacent to recent fire sites for instance. It seems that female heather beetles are weak fliers (is this a common female insect attribute on moorland?) and choose as open a flight path as possible. They can then penetrate the ‘thicket’ only so far. There they lay their eggs and so the hatchlings, lazier and even less agile than mother, feed on the heather shoots immediately available. In the process shootlets are ringed and thus starved of the stuff of green life, hence the very obvious colour change. The area affected in 2006, right across the moor, and up to 550 m OD on Great Links Tor for instance, was great enough to cause concern to commoners at the loss of winter feed, visits by the Heather Trust from its base in Dumfries and Galloway, and meetings devoted to the problem. A splendidly named ladybird Coccinella hieroglyphica feeds on the larvae (one a day), and a parasitic wasp Asecodes mento lays its eggs in them – in a ‘good year’ in almost every one. It is the best controller of heather beetles as pests that we have.

More invertebrate grazers exist on the moorland, though ‘the whole insect fauna is not conspicuous for its variety’ (Harvey) and none is so spectacular as the emperor moth, nor has such an obvious and immediate visual effect on the vegetation as the heather beetle. However, walking through heather and grassland habitats triggers the avoiding action of grasshoppers, almost spraying away from ones path, and that is likely to be the best evidence that plant biting is going on. The meadow grasshopper Chorhippus parallelus is the commonest shorthorn grasshopper of the drier grass moor, though a number of its cousins may also be around, and it is almost replaced on thicker peat with more sparse vegetation, as in recovering swaling sites, by the mottled grasshopper Myrmeleotettix maculatus.

The acid ambience of the open moorland means that shelled snail grazers are in short supply but the large black slug Arion ater is common enough in short-cropped grassland. While it varies in colour across its range it seems to be always black in the hills. Its close relation Ater lusitanicus is also present.

Of the smaller herbivorous mammals on moorland the short-tailed, or field vole Microtus agrestis (Fig. 133) is the commonest and certainly the most

significant grass feeder, though it also eats the bark of dwarf shrubs and very young trees, it may also develop a taste for the roots of sedges and rushes, notably Juncus squarrosus. Its known altitudinal range in Britain over-tops Dartmoor but purple moor grass moorland is its highest comfortable habitat and although it prefers to feed on the basal stems of softer grasses it seems to survive where coarse stuff may be the only choice. It makes runways through dense grassland on and just below the surface, and is a serious component of the diet of all the open-ground bird predators and of foxes. Both bank voles Clethrionomys glareolus and long-tailed field mice (or wood mice) Apodemus sylvaticus share the edges of the short-tailed vole’s general territory, especially at woodland/moorland boundaries and particularly where the latter is dominated by heather or other dwarf shrubs and bracken (Fig. 133). Bank voles also make surface runways but burrow more than short-tailed voles. Light snow often reveals the tracks and thus footprints of these small animals, and those of wood mice have been found on the high moor well away from their more favoured habitat. All these small mammal species appear to have a three – or four-year population cycle, with a steady increase in numbers to a climax followed by a crash as food supplies are overtaken. As the climax builds so predator numbers also increase, though there is little evidence that buzzards Buteo buteo (Fig. 134) and kestrels Falco tinniunculus, the only ones using our moorland consistently, lessen their territorial area at such times, allowing room for more pairs. In contrast, the passing harriers and short-eared owls may linger longer in spring and autumn in climax years. Hen harriers have at least one winter roost in the heather on the north side of Merripit Hill and their numbers may follow the small mammal ones upwards as even the off-season food supply grows.

Omnivores are not as rare among the small birds as one might suppose, and the skylark Alauda arvensis, the second most common breeding bird on the

moorland (more than 13,000 pairs in 2000 AD) is known to consume up to 45 per cent vegetable matter. While insects and other invertebrates are preferred when available and chicks are almost exclusively fed on animal material, still the fact that much of the plant matter is seeds means that the effect of these small birds on the vegetation mustn’t be discounted (Fig. 135). The commonest breeder, the meadow pipit, eats fewer seeds but as autumn proceeds so they become a more significant part of the whole diet. Linnets Carduelis cannabina are the most common finches on the moorland proper, and like most seed-eaters eat insect larvae at times themselves and especially feed them to their nestlings and fledglings as exclusively protein-rich animal fare. Small flocks of starlings Sturnus vulgaris patrol the open moor from Whitsuntide onwards out of the

villages, but the flocks build in size as the season progresses and substantial roosts develop in small plantations, notably in 2006 within the military compound above Okehampton (Fig. 136). The omnivorous starling has a taste for the beetle larvae growing up happily in cowpats and performs a valuable manure scattering function as it deals with the mature to elderly pat.

FIG 136. Starlings over a popular roosting site near Okehampton. (C. Tyler)

Wheatears Oenanthe oenanthe, whinchats Saxicola rubetra and stonechats S. torquata are insectivores par excellence and take the range of adults and larvae that are within their handling capability. Dartmoor is the wheatear stronghold of southern Britain, the density of breeding pairs outweighing other uplands south of the Pennines by three or four times. Wheatears like rock to be around, especially on steep slopes, and often nest in holes in dry-stone walls and among clitter (Fig. 137). They range here from 213 m to 579 m in altitude, so on the western slopes of the northern moorland block with that densest of clitter, the population rises to 3.66 pairs per sq km. RSPB surveys on the whole north Moor (north of the scissor roads) in 2006, estimated a figure of 2.6 pairs per sq km. The total number of pairs revealed by a DNPA/RSPB survey in 1979 was 1,182; in 2006, the estimate for the north Moor was 550. Overall, all moorland

insectivorous bird species have declined somewhat in the last 25 years. Whinchats seem to prefer sites with some bracken, though gorse can perform the ‘lookout’ function too (Fig. 138). Scattered bushes increase the attractiveness of the territory, but the combination explains to some extent the localised nature of the breeding population. Clusters occur in the Erme and Avon valleys, on Buckfastleigh and eastern Holne Moor, and at the head of the West Webburn below Birch Tor, so there is almost an eastern bias to the distribution. Stonechats reach higher numbers than whinchats, perhaps 1,500 pairs in good years compared with an estimate of 577 for their cousins, and the proportions are the same now. Stonechats are spread all around the lower slopes of the moorland block with a marked concentration on the commons around Widecombe and Haytor (Fig. 139).

In many ways the most mysterious of our moorland edge insectivores is the nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus, long known in plantation clearings, now increasingly nesting in heather and under bracken notably on Holne Moor and clearly the scourge of moorland moths (Fig. 140).

Swifts Apus apus, swallows Hirunda rustica and sand martins Riparia riparia use the uncluttered sky-ways over moorland as good feeding spaces and obviously take a huge number of adult insects. Swallows and swifts need buildings to nest in, but the sand martin lives up to its scientific name on Dartmoor and, despite the lowness of the vertical banks on the outside of moorland stream meanders it has used them on the East and West Dart, at Postbridge, Bellever, Dartmeet and at Prince Hall; on the Cherry Brook and at Cadover Bridge on the Plym. When Duchy tenants used their roadside pits in the growan, and thus kept their faces sheer-sided, up to the 1990s say, sand martins found them reasonable nesting sites, but neglect of their old purpose and the increase in their new use as car parking places seems to have put paid to that. On a different scale a decent-sized colony has long used the abandoned faces of china clay pits at Lee Moor.

Up the bird size scale slightly, mistle thrushes Turdus viscivorus feed on the moorland edge, they too are omnivorous and take beetles, their larvae and those

of others, as well as the seeds and fruit that all the thrushes consume. In autumn and winter, fieldfare T. pilaris and redwing T. iliacus flocks join them and rowan and hawthorn berries are a staple as long as they last. But the breeding thrush of the moorland is of course the ring ousel T. torquatus, the large black thrush with a white bib. Its breeding on Dartmoor is now very localised – rocks, ruinous buildings and walls have a magnetic attraction for ring ousels. They appear to thrive in the steeper-sided moorland valleys, especially on the West Okement and in Steeperton gorge on the Upper Taw in the north, in Tavy Cleave and at Vitifer in the abandoned mining girts (deep, narrow vegetated excavations) and ruins just a little further south. A small population shared Merrivale Quarry with the quarrymen in the 1970s.

Taking together this specialised interest of ring ousels in steep slopes, cliffs and mining relics, sand martins in growan and china clay pits and wheatears in clitter, the ecological connection back to Dartmoor’s geological, geomorphological and land-use evolutionary detail is as telling as the general link between the granite’s altitude and acidity and its moorland cover. It is in its way as important to the Dartmoor story as the connections between the grazing of dwarf shrubs and rambling and military manoeuvres (long sight and easy walking), between short-cropped grassland and car parking and

picnicking, and those implied by the outdoor gymnasium provided by boulder-filled streams and ruined clapper bridges (Fig. 141).

But we must return to the animals. In any discussion of the ‘lesser’ carnivore level of the pyramid of numbers on the moorland the reptiles and amphibians must be included. Adders Vipera berus inevitably top this particular list and take invertebrates as well as their infamous predation of the eggs and

FIG 142. Adders mating – the male is bright grey. (DNPA)

young of ground-nesting birds. They will consume vole offspring if a nest offers them up. They are summer creatures and favour bracken and gorsey slopes facing south (Fig. 142). Frogs Rana temporaria are found all over the moorland and well into the blanket bog, they are common in mires and valley bogs and surprisingly large numbers are stumbled on well away from standing water. Their part in the control of invertebrate numbers must be a useful one. The common lizard Lacerta vivipara also has a complete altitudinal range as far as Dartmoor is concerned and deals competently with the smaller insects, adult and young.

A few waders still breed on the open moorland, but in the last 100 years Dartmoor has never been the kind of popular breeding ground where they would play a large part in the food chain that is the basis of this chapter. A very small number of golden plover Pluvialis apricaria and more dunlin Calidris alpina have bred on the blanket bog between Cranmere Pool and Cut Hill up to the present, some 14 pairs of the former and 10 of the latter were there in 1979 (Fig. 143). By 2000, golden plover had dropped to five territories but dunlin occupied 15, and reached 24 in 2007. At lower levels, curlew Numenius arquata, lapwing Vanellus vanellus and snipe Gallinago gallinago share the honours but numbers of the first two species have fallen dramatically in the last 50 years (Fig. 144). While such a decline has been countrywide and habitat loss in the in-country the usual guess at the reason, that cannot be the case to the same degree on Dartmoor. Curlew and lapwing were to be heard in most extensive valley bogs and mires in the 1960s, even if at the rate of only one pair each per bog, but now they seem to be confined to extreme eastern mires as at Halsanger and Bagtor newtakes. Despite the fact that moorland wader habitats have not been actually lost, there is some evidence that vegetation height may be just getting to, and

FIG 143. Golden plover (centre frame).

staying at, a level that discourages wader movement and feeding potential, at least on the higher moor. Although work done by the Duchy of Cornwall, to encourage lapwing particularly, on the Prison Farm and in Spaders Newtake by mowing and making wet scrapes has so far had little success, at least it has revealed winter roosting of lapwing flocks, a phenomenon not recorded before. Lapwing traffic between Princetown and the Teign estuary seems to be a feature of the winter season.

All these four species are largely invertebrate feeders, and although most of us know them from winter sightings on estuaries and thus of their mud-feeding techniques those bills, long or short, are sensitive tools and pick up the available larvae and adult beetles and grasshoppers quite easily. Snipe, again, have an eastern bias with clusters around Raybarrow Pool, on Gidleigh and Throwleigh Commons, around Vitifer, in Muddilake, along the Swincombe in the central basin and in those eastern mires again including Blackslade. In 2000, numbers surveyed were above the 1979 figures (120) at somewhere closing on 200 pairs, with more than ten different males heard drumming over Foxtor Mire in that year. So the snipe story is different from that of the other waders, snipe appear to be holding their own, and they of course feed entirely on animals. Perhaps they are more ‘at home’ the year round inland, and not, as with golden plover and dunlin at least, at the edge of their breeding range where rarity and annual variation is inevitable.

Moving up the size scale again, and back with the grazers, rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus and red grouse Lagopus lagopus must come next (Fig. 145). Rabbits were encouraged historically by men from the early Middle Ages onwards, on Dartmoor by the building of warrens – usually long, low mounds of rocks and soil, and the trapping of their mammalian predators around those warrens. Warreners managed the construction, protection and harvesting of the rabbit colonies and place-name reference to the activity is widespread across the Moor, from Ditsworthy Warren and others in the Plym valley to Headland Warren below Birch Tor. The whole industry will be referred to again in Chapter 7. Short-cropped grassland is the rabbits’ favourite location and indeed partly of their making, certainly their maintenance. While the dense rabbit population of most of Devon crashed in the mid-1950s as myxomatosis took its toll, that of Dartmoor’s open moorland held up remarkably and it was suggested that the better ventilated homes whether in artificial warren or tor-and-clitter may have at least inhibited the transmission of the disease through the population. Young rabbits are a favourite food of buzzards and foxes, and badgers will dig out nests of the very young, so perhaps those predatorial populations benefited also from the ‘healthier rabbits’ of this moorland

FIG 145. Red grouse nest in purple moor grass in the 1970s.

terrain. Warrening is no longer, but rabbits are caught for human consumption still, sometimes by long netting involving a few people’s co-operation, more often as a solo operation. Before the myxomatosis outbreak rabbit was a serious component of the human diet. The Plym valley warreners certainly had a ready market in Plymouth from the seventeenth century on, and evacuees from the South East in Second-World-War Moretonhampstead complained of its regularity on their menu, being a meat they had not met before. Closely related brown hares Lepus capensis are not common on Dartmoor perhaps because they prefer the juicier stuff of man’s crops rather than coarse vegetable matter from upslope acid soils. Sightings of hares tend to be at the fringe of the moorland as though out for exercise from a farmland base rather than for serious grazing.

The staple food of red grouse is young heather shoots so without heather there will be no grouse. Numbers on Dartmoor have never been high since the introduction of the birds in the early nineteenth century, and no serious organisation of shooting has ever taken place, despite more than one release of 100 pairs (each time) in the first half of the twentieth century. A number of those surveys of birds of the high moorland from 1979 to 2000, referred to already, yielded numbers of pairs between 57, of which 24 were confirmed as breeding in 1979, and 30 territories in 2000, but scattered over probably 50 different localities, of which a dozen were in the southern plateau and the rest well into the northern moor except one pair under Birch Tor where a cock was calling in 2006. In the same year, a party of 11 birds were flushed by the author near Ockerton Court, near Cranmere Pool, in mid-summer – so breeding is still going on. Black grouse Tetrao tetrix on the other hand, although considered to be native, were thought to be declining as long ago as the eighteenth century. Despite the afforestation expansion of the 1920s – giving them more ideal conditions of shelter and food (young conifer shoots) – and the release of some new stock, numbers continued to decline and the species is now thought to be extinct on Dartmoor. Leks, or breeding male displaying sites, existed on Assycombe Hill at the edge of Fernworthy plantation, Merripit Hill and near Bellever within the last century, the last being active until the end of the 1940s. Blackcock were regularly seen at the head of the Plym in the same time span, sometimes moving around to take in Nun’s Cross and Foxtor newtake. Single sightings have been made at a wide scatter of localities right up to the late 1990s, which at least suggests that there are still some mysteries attached to the occurrence of these grazing birds. Grouse bird predators are not breeding on Dartmoor now, but foxes almost certainly take some chicks. Men, as miners, probably poached black grouse, and as foresters tried to protect the youngest shoots of their new spruces by shooting the last of the central Dartmoor population.

Foxes and badgers are the only mammal predators other than buzzards and us. Foxes are seen regularly, usually in lone sightings. They breed right across the moorland – tors, clitter and miners’ excavations offering numerous ideal sites for lairs (Fig. 146). The ‘countries’ of five hunts converge on Two Bridges, but since the ban on normal fox control a good idea of numbers is hard to come by. Some farmers claim to see more foxes together now, rather than the traditional loner of 1,000 years’ observation. The omnivorous badger is not a moorland resident of any widespread status, but ranges well out on to the moor from woodland and farmland setts, and is adept at digging out rabbit and smaller mammal nests as well as taking eggs and chicks from ground birds’ nests stumbled across.

And so we come to the major moorland grazers, the big mammals, without whom there would probably be little or no moorland – a fact we should remember as this tale goes on. The vast majority of the numbers involved belongs to, and is cared for, by hill-farmers. Until the last few decades that caring was not an altruistic operation. It was admittedly a way of life if it was to be successful, ever since softer agricultural alternatives were developed in lower country, say 2,000 years ago. But its industrial psychology was based on an economic exercise, bolstered in social terms since 1946 by ever-evolving public support: from the hill cow subsidy of that year to the Hill Farming Allowance (HFA) which in 2008 is being reviewed, probably for the last time. We must

FIG 147. Cattle are important grazers of all Dartmoor’s moorland components; here black cattle tackling a grass mosaic on Dunnabridge Common.

FIG 148. South Devons and Belted Galloways concentrate on a recent fire site – Scotch Blackfaced sheep and ponies prefer the short-cropped grass.

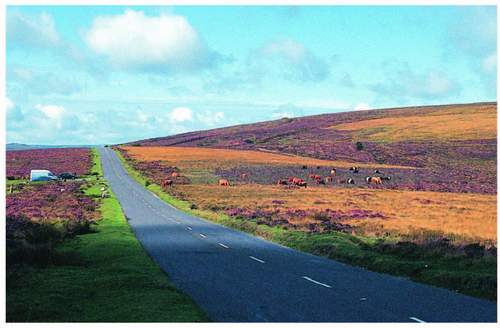

consider that in a deeper discussion about agriculture not long hence, but it explains the continuing existence in this century of a breed of men and women living at altitude as graziers and ensuring that the grazers, their stock, are still there in some numbers, though much diminished from those in the 1980s. Sheep, cattle and ponies graze, between them, all the vegetation types that have been described in the last chapter except pure bracken stands, though there are records of animals developing a penchant for very young bracken shoots with unhappy consequences. Grass invaded by bracken often provides a small store of palatable grass, useable as the bracken fronds die in the autumn having been difficult to access when the bracken was at full spread, which may account for heavier densities of grazing observed in that community on some occasions. Cattle, especially the real upland breeds – Galloways and Highland Cattle, and sheep wander up on to the blanket bog in high summer but ponies do not necessarily follow them in numbers. Happily however, the three species do complement each other’s favourite feeding in early summer, and as a last resort in hard winters. They are jointly responsible therefore not only for the generality of ‘moorland’ in which nothing of any significance except bracken and gorse is much above knee height and a good deal well below that, but also for the maintenance of the fascinating mosaic of plant communities with which that generality is vested. That we can walk in short order from close-cropped turf starred with tormentil into tussocky bristle bent, and out the other side into almost exclusive heather or equally singular western furze, then downslope into a sea of purple moor grass through which to slide into a valley mire edge of rushes and sedges is, from day to day, a grazing phenomenon. On the mid-altitude slopes Scotch Blackface ewes and lambs jockey with Belted Galloways and big ginger-brown South Devon cows (Fig. 148), ignoring the Dartmoor Hill ponies a pace or two away, all selectively biting their choice of the season. The sheep like the already-short stuff but are equally responsible for the fact that a huge number of 1 m-high gorse bushes are pruned in the winter into a mediaeval bee skep shape, something like a wigwam, all over this level of the moorland. From June onwards purple moor grass tussocks appear to have been sheared by the best Sheffield could offer as cattle bite them so tidily, and ponies bite the heart out of every matt grass tuft having yanked the rest of the matt itself out and discarded it, for us to find as scattered tiny bundles of thin straw with right-angle bends.

It is incredibly difficult to make estimates of the numbers of the three species actually grazing open moorland in 2008, let alone attach much credibility to historic figures. The latter were probably informed guesses or extrapolations from samples counted out there, or given to the ‘recorder’ by farmers in different

parts of the Moor. In modern times many farmers still regard their actual stock numbers as their business alone, and the demands of government and European Union ‘agri-environment’ schemes involving grazing densities only serve to confuse matters. At the simplest level of confusion non-grazing farmers, who nevertheless have a right to graze, have been entitled to participate in such schemes and be compensated for not grazing (which they weren’t anyway). The numbers of relevant stock, whether grazing or not, thus appear in totals kept by official bodies and are even published. To compound the problem of calculation further, many rights were registered under the 1965 Commons Registration Act as for the grazing of ‘livestock units’ in which one cow or bullock, one pony, but five sheep each equalled one unit. While useful for calculations of ideal grazing densities, such a formula conveniently hides the numbers of the three species involved for the owner, to the despair of the analyst of their ideal combination for maintenance of a particular plant-cover mosaic.

In 1808, Vancouver reported that ‘on the commons belonging to the parish of Widdecombe [sic] (and Buckland) in the month of October last there were estimated by gentlemen residing in the neighbourhood to be no less than 14,000 sheep, beside the usual proportion of horned cattle’. Those commons now total some 1,032 ha, so the sheep alone would have provided two livestock units per hectare. What ‘the usual proportion (of horned cattle)’ involves is anyone’s guess and although then most cattle were probably only there from May to October, they would certainly have increased the grazing density substantially in a year-round count. Vancouver admits there and then that:

the number of sheep summered and kept all the year round upon Dartmoor, the depasturable parts of which in a dry summer is one of the best sheepwalks in the kingdom, is not easy to ascertain, but if any inference can be drawn from Widdecombe and Buckland in the Moor, their numbers must be very considerable indeed.

In 1963, during the latter part of a notoriously hard winter, the numbers for ‘Dartmoor’ were estimated by MAFF as 40,000 sheep, 5,000 cattle and 2,000 ponies – and the spokesman claimed that that indicated a grazing density of one livestock unit to eight acres (3.2 ha), which suggests that MAFF was counting moorland newtakes as well as common land in its density calculation. It was of course the condition of ponies that made the news at that moment and although those figures were announced in Parliament, three estimates for pony numbers had been published locally only a fortnight earlier (Fig. 150). The Dartmoor Commoners’ Association said 2,000, the RSPCA estimated 3,000 to 4,000 and the Horses and Ponies Protection Association thought 6,000. That MAFF and the Commoners agreed may be significant, and charities have to boost their story in any case to stay in business.

FIG 150. Dartmoor hill ponies above the Cowsic.

In 1997 the Agricultural Development Advisory Service (ADAS) produced some figures that suggested that there had been a substantial increase in the cattle herd and the sheep flock on Dartmoor between 1952 and 1996 – thus straddling the 1963 statement just quoted. In 1996 it was estimated that there were just over 20,000 beef cattle and 130,000 ewes on the moor and that these represented nearly ten-fold increases over the period which, by counting back, indicates fairly low figures for the 1950s, even compared with Vancouver at the turn of the eighteenth century. But they also suggest a rapid rise into the 1960s presumably as support for farming continued to improve, if the 1963 numbers are valid. Even then, that sheep numbers more than trebled and cattle headage quadrupled in the next 30 years suggests that fairly important changes in the vegetation would have been triggered. The 1996 figures equal 46,000 livestock units and thus 1.3 units per hectare or nearly three times the grazing density 33 years earlier. Pony numbers are not included, such numbers were estimated again at 2,000 in the early 1980s for the NPA, and thought to be nearer 1,500 in 2006, when fortunately the pony trade started to pick up, and there was every hope that the population of true hill ponies would follow that trend.

Those still administering the Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) scheme in Dartmoor in the early part of the present century work on the basis of 0.225 units per hectare in the summer and 0.17 in the winter on dwarf shrub stands, and 0.365 in the summer and 0.23 in the winter on acid grassland as ideal densities for the maintenance of vegetation already in a healthy state, with lower densities for those areas where ‘restoration’ is the priority. They also estimate that only 9,000 livestock units of sheep and cattle were present in 2006 together with the 1,500 ponies already mentioned. A fall from 46,000 to 9,000 in ten years can only be described as a crash in animal population terms and not only reflects ESA formulaic dictat but also the ravages of the stock farming situation through those years in Britain as we shall see in Chapter 8.

The effect of the crash in stock numbers is already exercising those charged with managing the agri-environment schemes that are the medium for farmers in their turn to manage the moorland. Cattle numbers are currently too low to keep purple moor grass in proper check, and in the heathland mixtures or at the mutual edges of heath and grassland stands, heather is being suppressed by grasses. Short-cropped grassland, shared by the remaining sheep and the vast majority of human visitors, especially close to the road, is diminishing in area. A significant side effect of all this is the increase in fire risk in the winter or very dry summers, which are predicted to become the norm. While fire is a valuable tool in moorland management when properly used, in ‘wildfire’ terms it can do enormous damage immediately in the visual and biodiversity senses (Fig. 151). It

FIG 151. The morning after a wildfire above East Bovey Head in 1984. It ran from the Challacombe road across to the B3212. The wisps of smoke are because the arsonist tried again on his way to work – he was caught. One of the purest stands of ling on Dartmoor developed over the next decade.

can undo years of work geared to the restoration of some dwarf shrub communities, damage blanket bog irreparably if the fire gets into the peat, and sear the surface – even the sphagnum – of any valley mire in its path.

The other big mammals that graze Dartmoor moorland, though very occasionally, are deer. It is generally assumed that red deer Cervus elaphus arrive here having filtered southward across the lower Culm landscape from their southwestern stronghold in Exmoor, and some may drift across the Teign valley from Great Haldon and reach eastern islands of moor and perhaps the head of that valley. Moorland vegetation is not necessarily their favoured food, but root crops and kale are not common on high Dartmoor, woodland cover is thin except in the big plantations, but there edible shrubbery and grasses are confined to internal edges of clearings, at streamsides and along rides. Nevertheless odd stags and hinds are seen grazing in newtakes and have been accosted well out in open moorland, though then usually travelling to some purpose. Other species, notably fallow Dama dama and roe Capreolus capreolus, wander out of their valley woodland territories on occasion where moorland abuts the wood, but never go far from easy escape to cover.

The large feral mammal adults, recently (2006) joined by wild boar Sus scrofa, escapees but breeding, have no predators but man. Their offspring, at least very young fawns, like lambs, are somewhat vulnerable to foxes whose diet also ranges down to earthworms (in short supply in peaty soils) and beetles, and to dogs out of control, which includes farm dogs that have gone native. Carrion, especially on roads and in early summer, is dealt with by crows Corvus corone cornis – and magpies Pica pica closer to enclosed land. Ravens Corvus corax too, do some clearing up and specialise, to the extent of timing their nestling development, in the after-birth left by ewes after lambing (Fig. 152). They nested on many of the remoter tors until the middle of the last century but are now mostly confined to woodland and scattered tree sites largely at the edge of the moor proper. Buzzards, already mentioned, will also consume carrion and the placentas of sheep and ponies. In latter years peregrine falcons Falco peregrinus have reestablished themselves in abandoned quarries around the Dartmoor edge from which they range far and wide over the Moor, taking wood pigeons Columba palumbus and jackdaws Corvus monedula in flight as they find them, though they will take anything of that size and smaller that moves in the air and on the ground if it is foolish enough to expose itself.

THE ENCLOSED LANDSCAPE

The moorland edge, taken as the cornditch against the common and the inner wall of rough grazing newtakes where appropriate, abuts many more small fields than woods. Even counting the big plantations the physical length of that moor/field abutment is much greater than the wooded one.

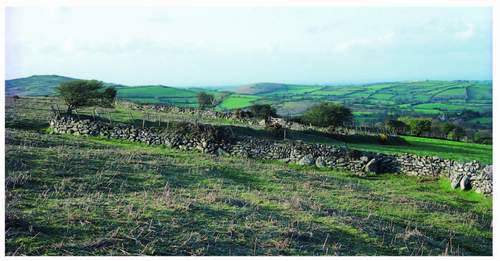

The animal traffic across the mutual boundary is likely to be one way, not very dense, and from bases within the farmland. The cornditches were designed to ensure no hindrance to game returning to the Forest and a one-way direction as far as domestic mammals were concerned with their sheer stone face to the common and a ramped earthen slope up from the field surface. Farmers didn’t really mind their own animals getting on to the Forest, but needed to prevent its domestic grazers entering their fields. Where it still exists that inner ramp of course has become a ready site for rabbit and badger excavation, and the whole thing lost its original commons boundary stock-holding efficacy when Scotch Blackfaced sheep were introduced in the nineteenth century. Their leaping ability (or ‘saltatory propensity’, as a judge in Okehampton County Court once described it when faced with a decision about responsibility for trespassing sheep from the common) demanded posts and wire on the cornditch summit if the age-old rule that any sole occupier of adjacent land had to fence ‘against the common’ was to be sustained (Fig. 153).

FIG 153. Cornditch above Moretonhampstead Moorgate on Shapley Common. The profile of the cornditch is clear inside the right-hand field. The modern need for a fence atop the bank as proof against the common is well shown.

Sheep or rabbit, the grazing is better in the small field than on the moor, the soil is considerably more accommodating of invertebrates than the peaty soil outside even if that improvement is only due to 1,000 years or more of enrichment by concentrated stock and application of lime, manure from the yard and occasional aeration by their overseers. The fields vary, as we have seen, and the two permanent grassland extremes – given that the arable acreage has shrunk to a few hundred hectares of kale, roots and a little grain near the edge of the national park – are hay meadows and the rush-and-purple moor grass pastures adjacent to valley mires and on some western wet slopes. The former, as must be expected, have the richer collection of plant eaters from the larvae of the butterflies and moths that relish the flowers in due season through the abundant grasshoppers to the small mammals, all well protected from their predators by the developing height of the grass-for-hay crop as the summer progresses. The

FIG 154. Barn owl. (C. Tyler)

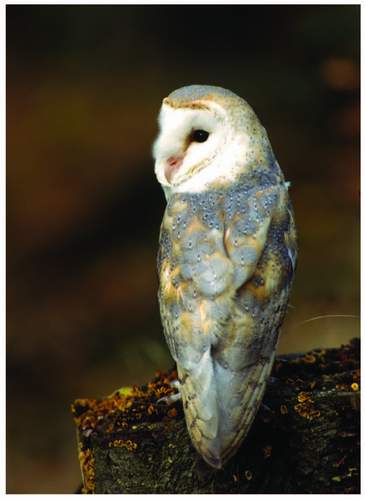

latter, the rhos pastures of the conservation vocabulary, are also described in the biodiversity literature as species-rich and in season they will seem so, but a strict botanical or zoological comparison between the best neutral hay meadow and best wet pasture does not yet exist. Given the decline of many wet meadow invertebrates in southern England, Dartmoor rhos pastures have assumed a new significance as strongholds for once much more widespread species. Chief among these are the marsh fritillary in Figure 130, a butterfly with over 40 colonies in Dartmoor sites or a fifth of the total known in England, the narrow-bordered bee hawk moth in Figure 131 and the double line moths Mythimna turca, the common blue Enallagam cyathigerum and the southern Coenagrion mercuriale damselflies and the mud snail Lymnea glabra. The snails and the larvae of all the moths and butterflies are the smallest grazers of rhos pastures, and themselves are prey to snipe, woodcock and now much-rarer lapwing, as well as birds from adjacent scrub like reed buntings, when feeding nestlings. Where purple moor grass is dominant the vegetarian vole population attracts barn owls Tyto alba all year round (Fig. 154), and short-eared owls Asio flammeus very occasionally pause to hunt over such stands on late summer and autumn passage.

The adult flying insects over both rhos pastures and hay meadows are prey to insectivorous birds if the field is close to the moorland or woodland edge and the moths especially are vulnerable to bats, of which the greater horseshoe bat

FIG 155. Grid over entrance to cave at Buckfastleigh allowing greater horseshoe bats in and out but denying cavers.

Rhinolophus ferrumequinum is by far the most significant in biodiversity assessment terms. Its Dartmoor breeding colony is based in caves at Buckfastleigh and feeding is fairly local (perhaps a 4-km radius) and thus confined to the farmed landscape in and outside the Park (Fig. 155).

Close to the same edge of the National Park two other rare omnivores occur: a few pairs of cirl buntings Emberiza cirius, common until the mid-1960s, but now very scattered through South Devon, breed in the arc of farmland between Chagford and South Brent and while seeds constitute the bulk of the autumn and winter diet, insects, particularly grasshoppers, are relished and fed almost exclusively to the nestlings. Woodlarks Lullula arborea have the same recent history and share the same kind of territory, appearing to need a combination of grassland, bare ground and scattered trees. Insects dominate their feeding, caterpillars being the favourite food of the chicks, but seeds, commonly smaller than those the buntings prefer, have to be the staple of the back end of the year. The woodlark’s song once heard is never forgotten and for many never bettered – nightingales shout in comparison. It is poured out from ground and tree, but characteristically continuous in a low circular slow orbit it is a real joy. With very short tails and a strenuous fluttering flight, woodlarks give an impression of feathered butterflies as they patrol their territory not far above one’s head. Seen close to, the striking feature is a pale ‘eye-stripe’ that runs right round the head separating the crown and crest from the face and neck.

There is of course the expected population of farmland birds in this landscape, less now than of old, but most species still represented. The year round seed-eaters – yellow hammers Emberiza citronella, all the common finches including siskins Carduelis spinus in increasing numbers this century, are joined by bramblings Fringilla montifringilla in the winter just as the fieldfares and redwings join the resident thrushes in the hawthorns and rowans at the roadside. Robins Erithacus rubecula, wrens Trogdolytes trogdolytes and dunnocks Prunella modularis keep the low-level insects at bay, while great, blue, marsh, willow and long-tailed tits Parus spp. deal with the higher-hedge and hedgerow-tree populations. The scattered trees of the farmscape of the eastern half of the national park and its western fringes are patrolled by green and great spotted woodpeckers Picus viridis and Dendrocupus major and many nuthatches Sitta europea, but treecreepers Certha familiaris (Fig. 156) and lesser spotted woodpeckers D. minor are few and far between now compared with the numbers seen in the middle of the last century. Any of these birds may be prey to hedge-hopping sparrowhawks Accipiter nisus if they are unlucky enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and the growing number of peregrines will take some, though the bigger vegetarians and omnivores, primarily wood pigeons and

jackdaws, even the odd pheasant Phasisnus colchicus, are more their style. There are still breeding stock doves Columba oenas on most farms, joined by eastern birds in the winter, and as many collared doves Streptopelia decaocto as anywhere else round buildings. Crows and magpies take their share of eggs and nestlings in farmland in season while scavenging generally the rest of the year.

Shrews Sorex spp. and hedgehogs Erinaceus europaeus are the commonest mammalian insectivores, mopping up beetles and innumerable larvae. The mole Talpa europaeus population is high and along with foxes, badgers and buzzards, regards earthworms as the most important protein easily available. While it ‘mines’ for them, the rest find them on the surface of well-grazed meadows during the night (the mammals) and in very early morning light, when all three species can be seen quartering the short grass at the right moment. As on

moorland, these three top carnivores all take young rabbits and dig out shallow hedgerow nests of blind babies – omnivorous badgers probably only manage a rabbit supper that way.

The biggest wild mammals of this walled and hedged countryside, as of the other components of Dartmoor’s cover, are deer. Roe are seen in the open in the daytime more than any other, but fallow and increasingly muntjac and sika browse the brambles and the meadow grasses close to cover, very early and very late in the day. All need woodland to lie up in and will rarely be seen far from it (Fig. 157).

THE DARTMOOR WOODLAND FAUNA

The mutual boundaries between stands of vegetation are usually richer in animal life than the hearts of either stand, for two populations intermingle here and others specialise in the ‘edge’ location, sheltering on one side and feeding on the other for instance. The same is true at the component landscape scale, and the function and richness of the edge is enhanced by the mobility of its dependants in any one place. Thus walking around or along the edge of a woodland block allows a glimpse of a loose community of species different from that observable within the wood or well away from its edge outside it. We will deal with the animals in the order used in the descriptions of the woods themselves.

The conifer plantations’ animals

The point about the edge community just made is almost more significant in the case of conifer woodland. For the outer edges, it is also complicated slightly by the fact that most plantations, even most woodland blocks in Dartmoor, have constructed boundaries. The high plantations especially were created in large existing newtakes whose original boundaries were granite dry-stone walls, and planting went right up to the wall. This has two effects, the edge is very sharp and the wall itself adds another potential dimension to the available habitat. Wrens for instance are great devotees of walls, almost confined to them in landscapes with no other shelter or cover, their mode of travel around and through them involving little apparent flight has led to the name mousebrodir, or mouse-brother, in bleak spaces like that of much of the Faroes. So even though the maturing plantation is not attractive to wrens they occur as sentinels of their linear territories at regular spacing along the boundary. Only under Bellever and Laughter Tors and well within the newtake plantation limits are there conifer edges without human interference between tree domination and grassland or heath. Here the Forestry Commission paused in its original planting, respecting the immediate setting of the tors and elsewhere of prehistoric artefacts.

Some plantation edges have lines of deciduous trees, often beech and thus decried as just as alien as the conifers by afforestation critics, but offering up a different population of insects as bird food and thus enhancing the edge community slightly. Many internal ‘edges’ also exist in the four biggest high plantations, and the ride sides and valley bottoms of Fernworthy and Burrator for instance have high rowan, sallow and alder numbers as avenues and groves. They, too, are now being carefully conserved by the forest managers, as they go through their first main harvest of pine, spruce and fir and then replacement planting, along with the encouragement of self-regeneration by at least the spruces. The sallows and alders especially are home to, and thus bitten by, a bigger variety of insects than the conifers. The sheltered position of these shrubs and small trees within the coniferous ‘compound’ adds yet one more quality to the high relative humidity of this habitat from the flying insect point of view. Not having to contend with the wind makes the feeding and courting of the lighter butterflies, moths, lacewings, damselflies, stoneflies, mayflies and caddis much easier (Fig. 158). Even the stronger dragonflies and the real heavyweights like longhorn and stag beetles, some of which are happy in both conifers and willows, find their, always spectacular, flights encouraged in this quiet air. Both Burrator and Fernworthy plantations wrap round the heads of substantial reservoirs (by Dartmoor standards) and in each case at least six streams flow

through the wooded slopes. Each also has a considerable length of leat – the famous Devonport Leat in the Burrator case – and a long one from the East Dart towards the Warren House, or more likely to the Ancient Tenement of Walna, originally and then to the Vitifer tin workings. Woods always contain more humid air than the space immediately outside them, but this density of water in channels within and large bodies of it just down valley much enhances the whole habitat and accounts for both the alder/sallow groves and the high insect population, much of which depends upon water, running or still, for its larval stages. Bellever, having the East Dart briefly alongside and Soussons, flanked by a small tributary of the West Webburn, and each having only one tiny tributary within the respective wood are arid by comparison. In both, sallows are confined to the banks of the two rivers. Water and its contained life, comes to the fore in the next chapter but its role, especially imparting another dimension to the fauna of the woods, demands its reference here.

The larvae of the terrestrial insects in these sheltered sites within the plantations are mostly vegetarian and their chewing ranges from the leaves of the shrubs and small trees to the herbaceous plants and even the lichens, relatively abundant in the southwestern clean air. They sometimes reach pest proportions in the sallow thickets. They are preyed upon by other larvae and adult beetles and of course the birds. The aquatic larvae are all carnivorous, and

deal with their smaller cousins and much that falls in from the overhanging shrubbery. The dragonfly adults, such as the golden-ringed Cordulegaster boltonii (Fig. 159) catch other flying insects on the wing whether hawking on patrol or darting from vantage points (hawkers and darters are dragonfly groupings based on hunting technique) while damselflies who fly much less strongly tend to pluck resting prey off streamside vegetation. The snail and slug population grazes as efficiently here as out in the open, and the beetles try to keep them under control. Small insectivorous birds are relatively numerous in these special sites within the plantations; the ubiquitous robins and blue and great tits are rarely absent and their coal tit cousins and goldcrests Regulus regulus, both happier in the conifers, come down to help out with the scrubby insect crop; blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla and willow warblers Phylloscopus trochilus join them for the long season. Grey wagtails Motacilla cinerea stick close to the streamsides and swallows and sand martins skim along the sallow and alder fringe overhanging the reservoir and larger river edges taking anything on offer but certainly the adult mayflies and stoneflies emerging from the water surface.

Reference has already been made to the current state of the plantation cycle and it should be clear that this is the time when the long dull maturing of the conifer crop is replaced by relative excitement for the animals as large sheltered clearings are made, soil is disturbed and, among the newly planted crop, ground vegetation burgeons. Weed pioneers move in first, other wind-borne seeds arrive – and seed stored since the first conifer canopy closed warms up and germinates. Ling seed, for instance, can wait easily for a conifer cycle to run its course. So, those birds already listed suddenly have a potential expansion of territory from their damper oases, and are inevitably joined by other insect seekers such as grasshopper warblers Locustella laevia who really do like the combination of coarse grassy vegetation and low sapling tree-top perches in young plantation sites for its own sake. Others stay because the already much-vaunted edge effect is greatly increased while the wind is still kept out, so spotted flycatchers Muscicapa striata may hold territory from mid-May round many new plantings. The slightly bigger insectivore that revels in these new clearings, however, is the nightjar already seen to be a moorland-edge predator. The moth population is high, the wind is less and these exciting birds are rewarding birdwatching targets on a late summer evening. If grasshopper warblers and nightjars inhabit the same area, then anglers’ reeling noises can last nearly all of the 24 hours.

It must now be clear that the irony of the plantations’ contribution to the faunal characteristics of Dartmoor is largely to do with secondary considerations. So far we have only dealt with the spin-offs from the plantation structure and it is the case that conifer woods of the planted kind from the moment the low canopy closes through to maturity are not rich in animals. Three bird species, however, are almost certainly only breeding in this National Park because these plantations exist. Crossbills Loxia curvirostra and lesser redpolls Carduelis flammea caberet are vegetarians (Fig. 160). Crossbills are normally resident further north and east but after a good breeding season and then a poor spruce cone crop at home, the population irrupts and often lands in Dartmoor (and many other southwestern forests) in numbers, sightings of up to 200 have been not uncommon since the high Dartmoor plantations began to bear cones. If the crop

here then holds the birds, breeding often ensues in the next season because crossbills mate and build very early, from mid-winter through to early spring. Records of certain breeding are sparse not least because crossbills nest very high up in the densely needled canopy, and thus much more is suspected than is proven in most years. But in 1997 crossbills bred in Burrator, Soussons and Fernworthy and probably in Bellever. They are regularly encountered in the smaller conifer woods around the Kennick, Tottiford and Trenchford reservoirs, and at King’s Wood and Dean Wood near Buckfastleigh. Lesser redpolls are much smaller birds (even smaller in Britain than in their Scandinavian stronghold) and devoted to middle-aged conifers for breeding, but happy feeding on alder and willow catkins as well as conifer seed. They were first recorded on Dartmoor in the 1950s, perhaps because the big plantations were then at their redpoll optimum. Up to ten pairs bred in Bellever at the height of the species’ stay. When the conifers grow on redpolls abandon them and move, so there is almost a nomadic pattern that looks for different stages in the plantation cycle at different sites.

The third and very different and (almost exclusively) plantation breeder is the goshawk Accipiter gentilis, bigger cousin of the sparrowhawk and having nearly the length and wingspan (over 1 m) of a buzzard. Goshawks are still rare enough here to have nest sites protected by deliberate lack of publication, but since 1990 a small number of territories have been established. These secretive birds nest at least 10 m off the ground, well into the dense cover on offer, though the total area of the tree block involved may not be vast and often involves deciduous trees at its edge. The Dartmoor goshawks take mainly middle-sized birds as prey, omnivorous crows, magpies, jays and vegetarian woodpigeons primarily, but rabbit and grey squirrel remains have been found at local nest sites too.

Coal tits and goldcrests have already been noted as sharing the sallow lines and thickets from their preferred conifer bases. Their insect fodder in their favourite trees is in the canopy and along the edges, where light is best, and the other tits will help them out quite often. Aphids are their staple, especially Adelges spp. on pine and fir and Elatobium abietinum on Sitka spruce, all of which damage their tree hosts but rarely to excess. An occasional great spotted woodpecker may use rare nest holes in mature pines, spruces and tall-enough dead stumps near the edge, and feed on pine weevil larvae Hylobius abietis under the bark of such stumps and broken limbs. Mistle thrushes seem to like the geometry of the plantation edge pines for nest foundation, and the lookout/singing post which the prominent evergreen often provides, but feeding demands short-cropped grass close at hand. In the clearings and new plantings after harvest the vegetarian field vole and wood mouse populations quickly establish themselves and get into their familiar four-year boom-and-bust cycle. Tawny owls Strix aluco often then seize the chance, move in and settle for the

FIG 161. Tawny owl. (C. Tyler)

time being (Fig. 161). Old crow’s nests can prove perfectly adequate for their breeding for what may not be a very long stay.

The deer species already identified as crossing and re-crossing moorland and fields may all spend long daylight hours lying up in the plantations and thus become the biggest animals in the forests. They, especially the fallow and red deer, will browse the brambles on the fringes and in the new clearings where they may not only bite the growing shoots of the little spruces but use the occasional sapling for territorial marking by ‘fraying’, scraping the bark with antlers so that it hangs off in strips. Roe stags often chase their latest hind in such tight circles that paths are worn in and around the clearings which they have adopted, quite distinct from the ‘racks’ or paths of their routine movements. Man is their only true predator and while there is no organised recreational shooting of deer on Dartmoor, the damage done proclaims populations which need management, and fallow especially are the subject of culling by stalkers working for and with deer control societies.

The denizens of the broad-leaved woods

Ninety per cent of the area of the native woods of the National Park is on steep and often rocky slopes and as we have seen that relationship is of very long standing, such that no other cover has intruded on the slope in question for a few thousand years. Thus the ground surface has only been disturbed by natural processes – downslope wash, tree fall and animal activity, except where man has made the odd track or platform or built a wall but, crucially, has never ploughed. Here is a shallow soil profile but with a thin tripartite zonation at the surface. Fresh autumnal leaf fall produces the litter layer (L), it is quickly attacked from below, bitten and eaten by mites, springtails and woodlice – which are themselves eaten by pseudo-scorpions, centipedes, millipedes, harvestmen, hunting spiders and others – and becomes the feeding layer of leaf fragments (F). The droppings of all those processors form the true humus layer (H). Earthworms move material from all three layers downwards and so the A horizon of the soil proper, the admixture of mineral and organic particles which hosts the seeds of all the woodland plants, is constructed. Since coppicing ceased, management of these woods has been minimal to non-existent and their floors are strewn with fallen trunks and branches in all stages of decay. The quarter of the British fauna that lives in rotting wood includes many species of the insects already named but all the slugs known in Britain are in these woods, many of them in this fallen timber and are prey to beetles and birds (see Fig. 121).

Bugs, their larvae and more slugs also contribute to the dismantling of the leaf litter and beetles and their larvae prey upon them. Of the woodland beetles,

the blue ground beetle Carabus intricatus is by far the most rare – only eight populations are known in Britain and five of them are in Dartmoor (Fig. 162), placing a real responsibility on those bodies who have shared its Biodiversity Action Plan (2001). The habits and ecology of the beetle are not well understood. It seems to be confined to ancient oakwood sites of the damper kind where the moss carpet and tree-trunk wrapping is widespread and it is most active in dampest times and at night. It feeds mostly on caterpillars and climbs – despite its name – high into trees to find them, as do other woodland beetles. Two or three species of bush cricket or great green grasshoppers Tettigonidae (Fig. 163) which also eat other insects can occur in these woods and in one site in the Teign valley a true cricket colony, of the omnivorous wood cricket Nemobius syvestris, has been identified, fortunately in a nature reserve.

While blue ground beetles and crickets are not going to leap out at even the careful observer, wood ants Formica rufa almost trip you up. They transport a vast volume of leaf fragments out of the litter to the preferred site of their colonial home, a tall dome built entirely of vegetable matter, often at the edge of the wood or alongside paths or rides, where some of the sun’s light and heat may penetrate (Fig. 164). Wood ants are large compared with other ant species, have an unmistakable red ‘waist’ and no one can miss the long lines of worker ants moving steadily to or from the nest. Most moving towards it will be carrying material for the apparently ever-necessary maintenance, but every now and then

FIG 164. Infant wood ants’ nest, at path side on Trendlebeare Down against Yarner Wood.

there will be one dragging a caterpillar, beetle larva or even an adult insect. They are omnivorous with a bias towards animal food and play their part both in cleaning up the woodland floor and keeping down the populations of other insects, some of which reach pest proportions on the continent. This last function gives these ants protected status in some countries. When you accost a wood ant by stooping towards it you would not think it needed any protection, for, despite your size, it will get up on its hind legs and threaten you. The workers have no sting but can spray formic acid from the rear end. Some birds, notably starlings, indulge in ‘anting’, landing on a nest they will pick up ants and put them under their own wings where the ants by spraying acid or eating lice do a pest control job for the bird. Professor Harvey, in the predecessor volume to this one, tells of a local Dartmoor belief that wood ants and adders do not coexist (his wife, who relayed the story to him, was brought up in Moretonhampstead, where I have lived for some 30 years). One of the significant effects of this folk tale was that it was felt safe to pick bilberries in woodland sites, but not out on the open moor – where ironically the ‘whorts’ are sweeter given their greater exposure to sunlight.

Off the floor of the valley-side woods the insect fauna is as rich as that in the litter if only because by the nature of their siting these woods are adjacent to rivers and streams so the terrestrial flying insects and their larvae are joined by aquatic adults even if high leaves and twigs are only, for them, places to sit in the sun. Higher relative humidity in any case is desirable for most insects. So, caddis, stone, alder and mayflies, midges and mosquitoes, all of which start life in the water, extend the total population. It is however already large, and the vegetarians are either bugs, notably aphids and leafhoppers, or the caterpillars of butterflies and moths. The latter, loopers like the winter moth Operophtera brumata and micro-moths, especially the green oak tortrix Tortrix viridana, can reach epidemic proportions and reduce the oak tree canopy from a distance to an autumnal state in early summer when their biting removes the leaves or rolls them up and damages them to the extent that they turn brown over large areas. The phenomenon, when it occurs, is best seen where there is a complete overview of the canopy; Bench Tor above the Double Dart upstream from New Bridge offers such a lookout.

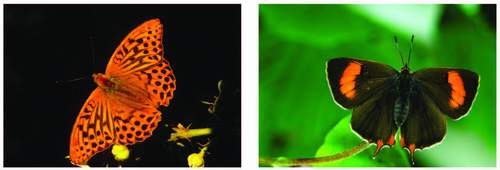

Of the butterflies, the speckled wood Pararge aegeria, brown, purple and green hairstreaks, Thecla betulae, Quercusia quercus and Callophris rubi respectively, and silver-washed fritillary Argynnis paphia are present in glades and along trackways in most of the eastern oakwoods (Fig. 165). White admirals Limenitis cammila have recently increased their numbers, as Harvey predicted they would, having hung on in Buckland Woods since the 1960s. High brown Argynnis adippe

FIG 165. (above left) Silver-washed fritillary, Hembury woods; (above right) Brown hairstreak (C. Tyler).

and pearl-bordered fritillaries Boloria euphrosyne also haunt the lighter parts of the northeastern woods and the Double Dart valley (Fig. 166). There are outpost colonies in the East Okement and the Tavy valleys, but their larvae both need violets whose own preferred place is under a light shade provided by bracken cover so good-sized clearings or sites sheltered by close woods are needed for breeding. Some of the woods of the Teign valley offer such combinations. The Dartmoor locations of the high brown represent a third of the UK recorded sites and those for the pearl-bordered fritillary are a fifth of them. Like the blue ground beetle they represent another significant challenge for twenty-first-century conservators.

FIG 166. Pearl-bordered fritillary, New Bridge. (C. Tyler)

While the insects occupy a large part of the ‘grazing’ layer of the woodland pyramid many of their species sit in the next one up and the omnivores straddle both. They are joined by small mammals, and the birds on the ground and in the shrubs and trees. Wood mice and bank voles are here as well as in the fields, and dormice, while present in other landscapes, come into their own in the oakwoods with hazel under-storeys (Fig. 167). They are right round the eastern and northern boundary of the National Park from South Brent as far as Okehampton and occupy woods and copses throughout the far eastern block. But they are almost entirely absent from the west, nor are they recorded from Wistman’s Wood or Black-a-Tor Beare. It is thought that there may be a sensitive level of relative humidity that influences their desire whether or not to stay in otherwise well-equipped woods. Even in the small compass of Dartmoor the physical pattern of the surface in altitudinal terms and the Lusitanian context exert pressure on the distribution of life forms. Shrews and hedgehogs represent the insectivores at the woodland edge, especially where a Devon bank provides the boundary rather than a stone wall. Adders and common lizards are not unknown under the better lit, low canopy and they both deal in insect food while the adders will take eggs and nestlings of ground-nesting birds and small mammals and their young.

The commonest ground-nesting birds in these woods are three of the warblers: chiff chaffs Phylloscopus collybita and willow warblers at the edges of the

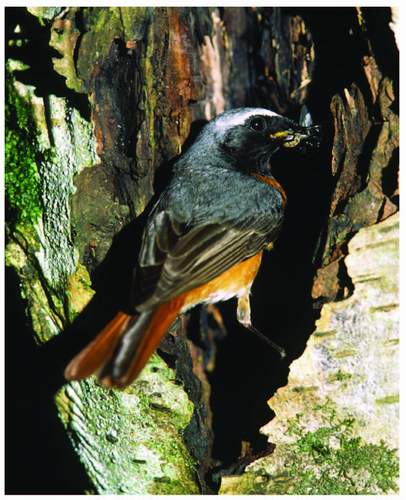

woods, and wood warblers P. sibilatrix throughout them. All three feed in the canopy on aphids and caterpillars, and nest on the ground in the shelter of a tussock of greater woodrush, a stump or a boulder, sometimes within a stand of bilberry, woodruff or cow-wheat – bluebells don’t last long enough or upright enough to offer sufficient cover. Wood warblers are heavier than their commoner cousins and have a very yellow tinge in the pale-brown standard warbler plumage (Fig. 168), as well as a yellow breast and belly. The male sticks very steadfastly to his columnar territory from ground to canopy, not to be dislodged by birdwatching visitors, and produces a two-part song, a tuneless extended rattle (tuneless because it’s above our hearing range) and quite separately a falling scale of long drawn-out notes whose music we can appreciate to the full. The two parts are not only separate but not necessarily strictly alternate either. Common redstarts Phoenicurus phoenicurus nest in holes in trees, rock piles or walls often close enough to the ground for an adder, say, to find the nest (Fig. 169). They too prefer the woodland margin that extends further inwards as a zone when the light does the same, either because of holes in the canopy caused by tree fall or because the edge is occupied by silver birch or ash both of which offer only a light shade. Redstarts appear to feed at all levels in the trees and on the ground but the males usually sing from the canopy top, more easily seen therefore than their companions because of the usual steeply sloping sites which one can often scan from above or from within through the nearer trees. Redstarts are

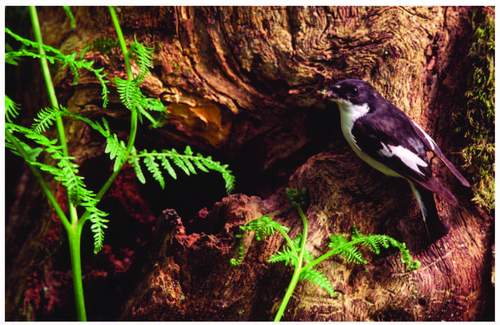

insectivorous, as are the pied flycatchers Ficedeula hypoleuca who complete, with the wood warblers, the triumvirate of British upland oakwood indicator birds. The arrival of all three is eagerly awaited on Dartmoor every April.

Like the wood warblers, pied flycatchers may be present throughout the wood and while hole-nesting they rarely occupy holes close to the ground (Fig. 170). The story of their settlement of Dartmoor woods is an intriguing one. They were known to pass through, on the way to their then southernmost breeding location in the Forest of Dean, in the 1940s and when the Nature Conservancy acquired Yarner Wood, near Bovey Tracey, in the early 1950s a pattern of nest boxes was emplaced which enchanted the passing birds to the extent that they stayed, multiplied and have since spread right round the Moor’s wooded valleys with and without the aid of artificial nesting sites. The whole original scheme was the brainchild of Bruce Campbell, enthusiastically supported by birdwatching Max Nicholson, the director general of the Nature Conservancy of the day. Every nestling born in a Yarner nest-box has been ringed and so the history of the

generations and of the rate of returning to breed is entirely documented over some 50 years. The success of the experiment inspired more nest box provision and numbers have been set up in bigger woods all around the moorland edge – notably dense in the Teign valley and that of East Okement but also in the Dart, the Avon, the Yealm and the Erme valleys, and a fair population returns each summer to the Meavy valley near the Burrator dam. The birds have shown that, while nest-boxes help with the invitation to stay, they can also find more natural holes than were thought to be available, and in White Wood under Bench Tor, all the 2006 breeding pairs were in such sites.