CHAPTER 7

Working the Landscape: Dartmoor

Men and Their Masters Through

Historic Time

The villeins, bordars and serfs mentioned in the Domesday (Book) must have been clearing their lord’s waste lands for settlement at a very early period. Of these shadowy people nothing is known except that it was their toil and their industry that formed the landscape…They were the forbears of the present owners and occupiers of the farms whose ancestors have lived in the district ‘time out of mind’…and can have known little or nothing of their overlords…or the complication of several holders between…the King and the actual occupier.

C. D. Linehan, 1962

All the subjects of the parts of the ‘natural’ Dartmoor story that have gone before in this book have become intimately involved with men at work at some time since their own inception. Indeed reference has had to be made to that work, as some components of the natural history of the Moor have been portrayed, to complete that part of the picture. It is the landscape effects of the work that provide the theme for this chapter. The surface, the rocks from which it is fashioned, the water running on it and off it, that that grows on it and the soils developed from their relationship, even the interplay between them all that has come to characterise the uniqueness of Dartmoor, have at some time offered livelihoods, satisfactions and profit to men. The slope, the flat, the height, the aspect, the channel, the boulder, the gravel, the ore, the clay, the peat, the heather, the grasses, the gorse, even the bracken, have been jointly and severally exploited – mostly in the nicest, though occasionally the most selfish, of ways. Much of that exploitation has gone on throughout the last 4,000 to 5,000 years and most of it persisted through nearly all of the last 1,000. In just a little more than the last 100, the subject of the next chapter, new incomers have planted commercial softwood crops, stored water for distribution to half a million people elsewhere or have crawled or yomped from one firing point to another, all because there was this space, at this height and with this climate. All, except perhaps the soldiers, or the miners and quarrymen on occasion, have ‘quietly enjoyed’, as the tenancy law has it, their moiety of that space for their life and work. In about that same length of recent time, ramblers (of different kinds) have walked and horsemen have ridden over the moorland and between the fields for a new kind of enjoyment and some others have even profited from that.

A PREHISTORIC REMINDER

It has thus been inevitable that, since that moment in Quaternary time rehearsed at the beginning of Chapter 3, men and women have been drawn into the developing story of the evolution of what we now know Dartmoor to be. They, as animals, hold a place in any pyramid of numbers and in the relevant natural food chains, even if humans are neither ‘top carnivores’ in the pyramid nor much of a link until the end of the chain. But the postglacial evolution of the vegetation cover has to include man as more than an animal. Mesolithic men, as we have seen, improved their hunting and gathering grounds and, DNA studies suggest, were the founding fathers of a succession that has persisted in western Britain at least throughout prehistoric and maybe all of historic time too. They thus began a vegetation management process, and modified it as new cultural ideas, skills, experience and practices were brought to Dartmoor by ‘new men’, probably up the Atlantic coast and across the Western Approaches. Our well-worked archaeological cultural time zones are still very important reference phases but increasingly the evidence is that cultural change was a handover matter rather than a displacement of whole peoples by newcomers. So, in Neolithic time, the making of better glades and grazing for game and thus easier hunting of the Mesolithic was integrated into a short-term and very nomadic clearing for some growing of crops and penning of animals, but still with ‘hunting and gathering’ as part of the lifestyle.

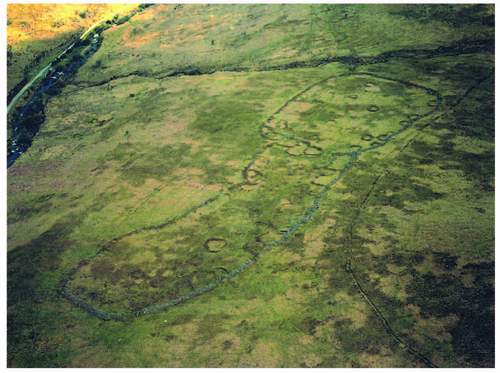

By the Bronze Age the ‘agricultural’ part of that formula had clearly taken over and the comprehensive clearance of the high-level forest, which might by then in any case have come to resemble savannah, was rapidly followed by the need to organise the first widespread enclosure on the gentler slopes and flats above the gorges as Figure 72 showed. This pattern will be examined more thoroughly before this chapter ends, but men were, by then and into the Iron Age, influencing the mosaic of surface plant cover and turning a good deal of it into a fairly dense system of human land use. Doubtless each of the phases of evolving culture contained masters and men, and corporate activity demanding leadership is implied on more than one front. From Roman writing we know of British masters. Before that the Bronze Age ceremonial structures and burials we have identified do not constitute a large enough ‘graveyard’ for the total population calculable from the hut circles still on the ground however carefully the generation factor is fed into the equation (i.e. not all the huts were occupied at the same time and a rate of one new hut per group per generation has been suggested). Those community structures must have been the celebrations and graves – whatever their other territorial functions – of the ‘masters’. The hut groups and pounds like Grimspound and Riders Rings proclaim village communities that have throughout time bred leaders (Fig. 193). Those leaders surely decided who did what, who specialised and who laboured day to day. In crises like defence of the territory when threatened and necessary communal

FIG 193. Riders Rings looking south: a large and complex Bronze Age settlement on the lip above the Avon valley (the road to the reservoir dam runs alongside the river in the top left-hand corner). Here, both huts or roundhouses and rectalinear ‘yards’ are attached to the outer wall of the pound. A nineteenth-century leat runs in an arc above the settlement on the right.

routine such as the earliest drifting of stock, both requiring ‘all hands to the pumps’, someone had to be in charge. We shall see that organisation (and the implication of possession of, and defence of, the territory) has persisted as time has passed as a prime motive in Dartmoor management.

Most recent interpretation from the ground alone suggests that Iron Age people did not take over the whole of Bronze Age Dartmoor, and that fits with the new thinking that cultural change is not effected simply by ‘mass inward migration’. The surface legacy of the late first millennium BC is of some nine ‘hill forts’ at the edges of the moor and a dozen other settlements. The so-called forts on summits and spur ends are crowded on the east and northeast and Holne Chase, closely related to the Dart ‘entrance’, is notionally the furthest in, or moorward. The same structures occur at Hunters Tor at the north end of Lustleigh Cleave, at Prestonbury, Wooston and Cranbrook either side of the Teign’s gorge; then on East Hill near Okehampton and on Brentor down the west side. There is then a big gap on the anti-clockwise ring until Brent Hill overlooking the Avon and Hembury Castle above Buckfast and thus not far from Holne Chase. They may have had little or no military significance despite their popular description, for 11 ‘other’ Iron Age settlements, involving fields, are inside (in the Dartmoor sense) the fort circle which might otherwise have been interpreted as an Iron Age frontier, and apart from Leigh Tor, across the river from Holne Chase, are not closely related to any of the forts. They all pose problems in precise dating terms and to a layman most hint at occupation which may begin in the late Bronze Age and recur in mediaeval times. It should surprise no one that any site might yield the same potential to new subsistence farming settlers (whatever else they did) after gaps in occupation. At Foales Arrishes, below Top Tor, Metherall and Kestor either side of the South Teign west of Chagford and on Shaugh Moor there are huts and small fields. At Kestor iron was smelted and wrought but exactly when is less than clear, and pollen analysis suggests that this site was occupied at the same time as a Late Bronze Age one on Dean Moor in the southeast. The fort-like ‘tor enclosures’ at the Dewerstone above the Plym and Whittor above Peter Tavy are only separated from ‘forts’ by their complexity, and in both cases occupation (or construction) may extend back to before the Bronze Age. Iron currency bars from Holne Chase, pottery in sites already named and at Smallacombe near Haytor, and two Greek coins of 92 BC at Holne are all within the concentric rings of the forts and the more workaday settlements. So, it seems clear that the last 500 years BC saw a withering of settlement at the heart of the Moor but a clear zone of Iron Age development around its outer edges; and we know that the climate had deteriorated during that same time.

The Romans, as far as we can tell, by-passed the Dartmoor mass close to its northern flank. A mile and a half south of North Tawton and close above the River Taw is a Roman signal station, earlier a staging post, with some three miles of the course of a Roman road leading to it from the east as though from Exeter, the only substantial Romano-British settlement so far west. The suggestion is that there was Roman traffic to Cornwall where metal was the probable prize, making the Dartmoor avoidance a small mystery. Maybe no one told them there was tin, copper and iron up there; maybe it was rainy enough to make lower coastal sites further west a more attractive proposition despite the distance; maybe we haven’t found the evidence yet. Perhaps the proto-Cornish were better traders than the highland Dumnonii (the tribal name the Romans learnt, or gave, to the native British they found in Devon). The Dumnonii did not defend their territory but made some peaceful arrangement with the Romans. Exeter was already a British settlement and became a Romanised tribal centre where British masters and their men learnt about city life. But having been walled properly in about 200 AD it had been thoroughly neglected and abandoned, by the masters at least, at the end of the fourth century. Whether this whole interlude was much of a distraction from Dartmoor management and development is not clear. Dartmoor people had perhaps already begun to keep themselves to themselves.

THE SAXON LEGACY

Quite soon ‘formal’ Saxon newcomers penetrated beyond the inward-facing Dartmoor frontier of the British natives they overtook, whether peacefully or by military advance. Those alternatives arise because we know that Anglo-Saxons from earlier settlements up-Channel had landed on and settled the east-facing coast that stretches southward from Exmouth to Start, before the military advance of the west Saxons had reached east Devon. The Frontispiece map shows that coastline well. Stokenham, Slapton, Brixham, Goodrington, Paignton, Shaldon, all proclaim this early Saxon settlement. They may have ousted the Britons fairly gently at first from the coastlands. At Slapton, in the extreme south of the South Hams, Wallaton Cross on the present inland parish boundary suggests that Slaptonian Saxons in their ‘slippery place’ lived alongside ‘the place of the natives’. The equable South Hams was named by farming Saxons – an extant charter of 846 AD (in which Aethelwulf, Alfred’s father, conveyed land to himself from that which he held for the people) confirms that. But the Dart, which crosses that landscape, bears a British name almost certainly related to those lower reaches of the river’s course, at least half of whose length is tidal, between continuously oakwood-clad valley sides. What is clear is that the main

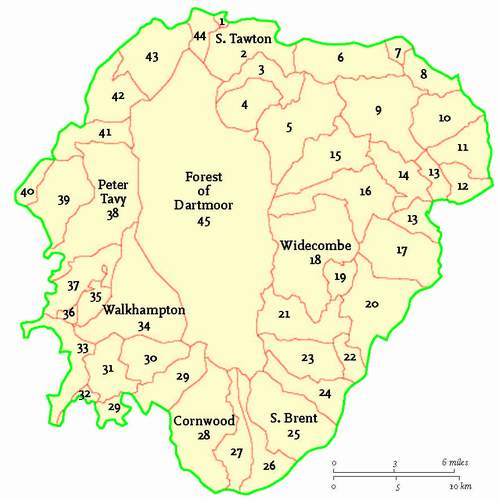

FIG 194. The modern map of Dartmoor parishes (those with tiny areas within the National Park boundary are not identified). All but six are identifiable in the Domesday Book, though not always by name. KEY TO PARISHES: Seven are named on the map and all are numbered: 1. Sticklepath; 3. Throwleigh; 4. Gidleigh; 5. Chagford; 6. Drewsteignton; 7. Cheriton Bishop; 8. Dunsford; 9. Moretonhampstead; 10. Bridford; 11. Christow; 12. Hennock; 13. Bovey Tracey; 14. Lustleigh; 15. North Bovey; 16. Manaton; 17. Ilsington; 19. Buckland-in-the-Moor; 20. Ashburton; 21. Holne; 22. Buckfastleigh; 23. West Buckfastleigh; 24. Dean Prior; 26. Ugborough; 27. Harford; 29. Shaugh Prior; 30. Sheepstor; 31. Meavy; 32. Bickleigh; 33. Buckland Monachorum; 34. Walkhampton; 35. Sampford Spiney; 36. Horrabridge; 37. Whitchurch; 39. Mary Tavy; 40. Brentor; 41. Lydford; 42. Sourton (and lands common with Bridestowe); 43. Okehampton Hamlets; 44. Belstone.

Saxon penetration of what we call Dartmoor was via the upper valley system of the Dart and they, it may be, who transferred the coastal river valley name to the moorland of the river’s birth.

The Saxons had completed their colonisation of the lower end of the central basin of the Moor and the middle east well before 1000 AD, for almost every twenty-first-century village and parish here, and many a manor still lending its name to a smaller settlement, is entered in the Domesday Book and thus had some value in land-use terms by 1000 AD (Fig. 194), and to their holders (to distinguish them from the actual occupiers) long before that. Some other Saxon essays into the Dark Age moorland/woodland complex must also have taken place, but only from the eastern side, up the valleys of the upper Teign, the Bovey and the Wray and through the cols between them. Otherwise Saxon settlement is confined to a zone outside the moor, though some like Gidleigh and Throwleigh (classic secondary or pioneering woodland clearing names), Mary Tavy, Shaugh Prior and Harford are close to its frontier. South Tawton and Sourton, and from Lydford through Peter Tavy to Whitchurch, Sampford Spiney, Walkhampton, and on to Cornwood, South Brent and Dean Prior are all a step away from the moor but had connections with it in Domesday.

The Domesday Book records more Saxon villages unlikely to have been settled by a Dart basin approach. There is a string of interestingly high-level settlements: Hennock, Bridford, Drewsteignton, Moretonhampstead, North Bovey and Manaton in the northeast, and Belstone isolated in the north, all above 200 m OD (Fig. 195). Belstone and Manaton are well above that and both

FIG 195. The view out to the east from high-level hillside Hennock across the Teign valley to Great Haldon – Teign village is the one-street settlement down below.

are closer to the moor itself. Well off Dartmoor proper and lower but close enough to influence the land use of its margins, are Christow, Dunsford, Okehampton, Bridestowe, Tavistock and Yelverton round the north and western arc and Buckfastleigh, Buckfast, Ashburton, in the lowest part of the Dart catchment, and Bovey Tracey all on the south and southeast.

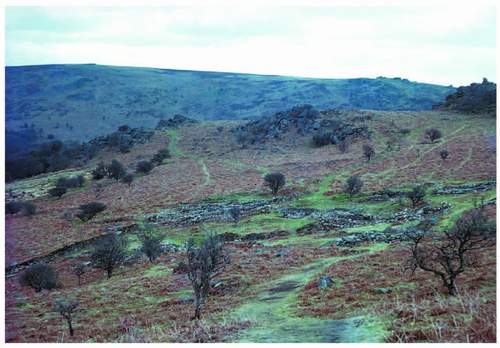

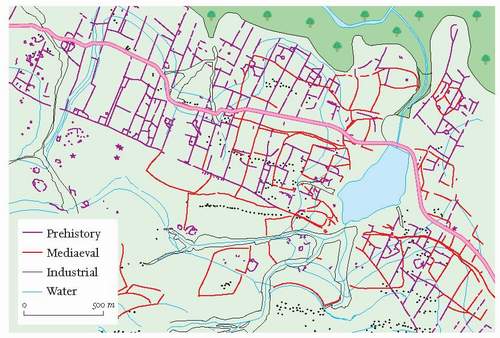

As we saw at the outset of this twenty-first-century version of the whole Dartmoor story, the Domesday record adds up to a demonstration that the people of the Dark Ages laid out the agricultural enclosed landscapes up to 300 m OD more or less as we know them today. Their contribution to the scene has lasted at least as long as that of the Bronze Age folk did at higher levels in their day. Between them this pair of developer cultures produced two topographically overlapping patterns that, under their separate climatic regimes, cover the ground below the blanket bog. The overlap is evident in both directions. Bronze Age reaves persist in lines within the fields of the valleys of the upper Dart system, and Saxon and mediaeval enclosures, dwellings and plough marks are discoverable out among the reave patterns on the open moor (Fig. 196). No culture from 3,000 BP has neglected or discarded any earlier pattern, wall or shelter that it has found useful and much subsequent work has respected, as archaeologists put it, what it found at the

FIG 196. The Holne Moor palimpsest, mediaeval remains and tin workings, superimposed on the prehistoric pattern of Figure 72 (after DNPA).

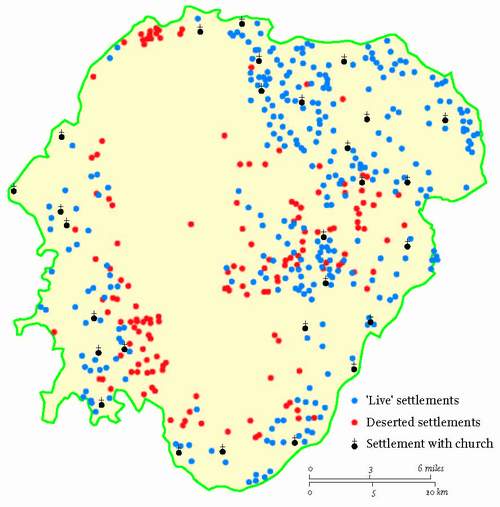

surface. Only new technique or climatic force majeure has caused older lines to be slighted. However, while many Domesday manors have survived in some form, many also ceased to operate wholly as early as the fourteenth century, and some farmsteads and bigger settlements first recorded in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries have not lasted until now as the map at Figure 218 inter alia indicates.

Conversely, towards the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth there were additions to those two grand patterns – notably within the ‘Forest’ – and thus involving what many still regard as intrusions into the ‘pasture’ which both pattern-makers had protected, even if only by default. The Duchy of Cornwall, the archetypal ‘master’ of this chapter’s heading, promoted the development of Princetown from scratch and to a lesser extent of Postbridge beyond its Ancient Tenements. The enclosure of the large newtakes from the open moor between those two places and beyond, and the creation of some leasehold small estates on which among other things the first attempts at afforestation were made completed the Duchy’s most energetic 100 years. Outside the Forest the same period saw the initiation of granite quarries and of large-scale clay mining. The building of the turnpikes straddled the Forest, which was clearly meant to benefit from their passing through, but their planners, their take-offs and their targets were outside it. To them we must return.

Dartmoor as a place or even as a concept is not referred to in the Domesday Book. But as it, the Book, was recording land use and land-use potential and thus value, that need not surprise us. The Moor was a ‘royal’ hunting ground in Saxon times and thus belonged to the Crown. Its value was to the monarch and his court alone as a place of recreation and perhaps source of a change of meat in a dominantly meaty diet, so had no calculable price nor was one seen to be necessary by the inheriting monarch’s own surveyors (quite clearly in Devon organised and briefed by a Saxon administration of clerics who knew how the land-holding system worked and had managed royal lands before the Conquest). We shall have to refer to 1086 AD again

Because, despite our frustration at the things the Domesday survey doesn’t say and especially that lack of help about the whole moorland extent, its timing is a convenient marker in assessing men at work in any landscape. Convenient, partly because of its reference back in most entries to very early 1066, before the last great imposition of power change on the English happened, and partly because it is so close to the beginning of the second millennium AD. That is, about halfway through historic time so far and from whence an increasing amount of documentary evidence has helped Dartmoor historic scholars, just as it has helped their peers all over England. There are many of them, their writings are mostly still easily available and those prior to 1992 fill a 363-page published bibliography. Most began as specialists, but many eventually generalised. It is not the purpose of this chapter (or this book!) to emulate any of them, simply to draw on their work, to add another interpretation here and there perhaps, and hopefully prompt the reader to seek out the more specialised contributions if more breadth and depth in any particular area is sought.

INTO THE MIDDLE AGES

Throughout this last millennium, and never forgetting the specialist tradesman, those niche marketeers who set out to satisfy local needs for moorstone, quarried stone, wrought metal, gravel, peat, wood-fuel and structural timber, two occupations have dominated Dartmoor’s working scene. Farming and the working of tin have produced more widespread and lasting landscape detail than any other work. Prehistoric farming, as we have seen, can claim to have created the present cover of at least half the surface of what is now a national park and by their grazing and burning historic hill farmers have inadvertently sustained it. They and their close neighbours have more deliberately maintained the enclosed remainder. The tin workers’ etching of the moorland, lying uphill from the enclosures is still very clear to any thoughtful observer. We have already seen that the junction of those two terrains, open and enclosed, has been a blurred zone throughout human time here. The precise position of the boundary at any one time and in any one place depended upon the fortunes of agriculture locally, regionally and even nationally. The intensity of tin working also varied across the centuries, equally dependent upon trading beyond the Exe and beyond the coast. That also meant that at its economic peaks the legally privileged tinner could cross the same boundary, between moorland and farmland, but downhill.

Whilst farming and tinning and their surface effects must be traced through historic time it is important to register first that they were not always separate or exclusive. It is clear that farmers sometimes worked tin, and that quasi full-time tinners grew crops and kept stock. There was doubtless a great variation in range of time spent, by either individual tradesman on the other’s specialism, and this dual part-time work is typical of most historic metal-mining areas. There is also plenty of evidence that men and their masters were engaged in both industries. Tin working had its shareholders and its ‘waged tinners’. Farmers forever have been landlords, tenants and free labourers or hinds (hired hands in Devon). Some farm workers, even beyond the first millennium had no independent status at all. The slaves and serfs still recorded in Domesday had existed since the Iron Age, the ‘landless’ are recorded for a few centuries more in rent and tax surveys and some mine workers as late as the nineteenth century were rewarded with tokens they could ‘spend’ only in their employer’s store. There were degrees of shade among all of Linehan’s ‘shadowy people’ throughout the millennium. But it is they who did the work that left us with the rich tapestry that geology and climate had invited them to embroider across the Dartmoor surface.

MINERAL WORKING AND THE LANDSCAPE

The working of tin

No evidence on the ground to prove prehistoric working of tin on Dartmoor has yet been discovered, though it is assumed by many. Dartmoor Bronze Age men had bronze articles, and scrap bronze from elsewhere was available to them (bronze is an alloy of copper and tin). Smelted metal has been found inside huts but rarely alone or with only other Bronze Age artefacts. A hut on Dean Moor (where the Avon reservoir is now) yielded a ‘drop’ of tin and some tinstone, but most similar finds have been accompanied by at least mediaeval ones, implying that the hut’s structural remains proved useful shelter for later workers. The earlier reference to the Kestor hut with iron-smelting and iron-working evidence, but doubt as to the date of the work, supports this principle. We can only imagine that Bronze Age folk found pebbles containing tin as readily as their many successors, but we have no idea how sizeable were their individual ‘works’ on the ground or how widespread they were over the moor. This appears to leave the landscape contribution field clear for the tin workers of the historic period, at least for the time being. More intensive research and new techniques may change that perception at any time.

FIG 197. Tinners’ hut in the side of a streamwork trench – Beckamoor Combe on Whitchurch Common.

It is the extraction of tin by at least three different processes that has left the most significant set of features in the moorland landscape associated with the whole industry, collectively known as tinworks. Structures, such as shelters, tool stores, blowing houses (smelters) and tin mills are also scattered over the moorland and within the enclosed landscape, but even compared with prehistoric hut circles their surface legacy is small in scale (Fig. 197). Shelters, as one would expect, are usually where extraction took place, but the remains of buildings associated with processing the ore may be some distance away, for some processors probably collected and dealt with raw material from a number of scattered sites.

Tin occurs in lodes (to a miner), veins or collections of veins to a geologist. Lodes run through the granite and now and then outcrop at the surface where streams may erode them along with all else that lies in their course. Thus downstream of the outcrop mixtures of fine and coarse debris have been deposited including tin crystals as fine as the accompanying sand, and pebbles of various sizes containing tin. Such deposits, forming ‘tin ground’, occur alongside most moorland streams and may lie in and on the floodplains and beds of the larger rivers well off the Moor where they have also been worth working in the past. That work could involve quite elaborate channel creation to divert the river while working through its bed, well seen in the Dart below Dartbridge at Buckfastleigh.

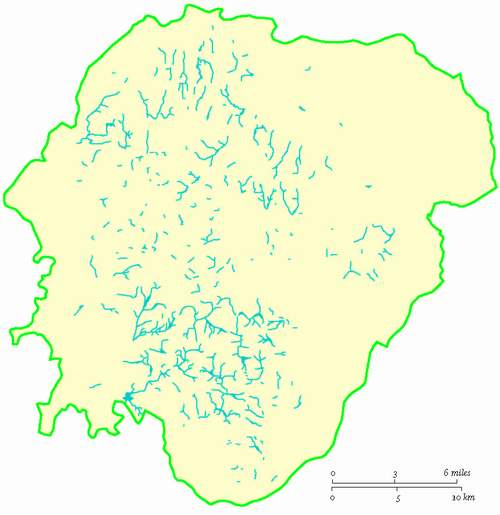

The extractive tinworks on the moorland have also been divided by archaeologists into streamworks and mines, and both types, themselves, subdivided. The surface legacy of streamworks is by far the most widespread over the whole Dartmoor surface, and individual sites are much more extensive than either mines, which includes opencast working, or the relatively tiny (in landscape terms) exploration pits associated with prospecting for tin-bearing lodes. The majority of streamworks are alluvial, or as that adjective implies, in the bottoms of valleys however shallow. The others extend up gentle hillsides, and for the tin ground to be worked demanded that flowing water was brought to the favoured site to assist in the separation of tin crystals (as ore) from sand, silt, clay and other material of coarser calibre which may also contain tin. The water was brought by leats, which have been referred to already in more than one context, and often stored temporarily in small reservoir pools above the working site to allow sensitive control of the discharge as needed. The flow had to be just right to shift the lighter fraction of the alluvium but not sweep away the tin crystals which are heavier and thus can settle out given exactly the right conditions. Early on of course primitive searches for the metal depended upon the fact that a pebble containing tin weighs more heavily in the hand than a similar sized one without any such ore.

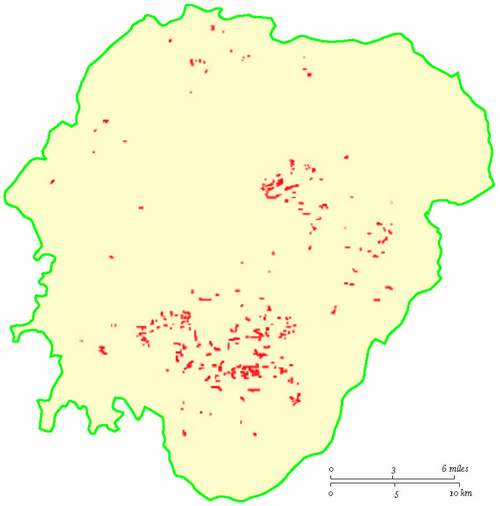

Streamworks are especially dense over the southern plateau – there is hardly a square kilometre without such modification of the surface (Fig. 198). In the north a zone of lengthy excavations stretches southeastwards from a Cosdon to Great Links Tor baseline to Hameldown. Both these areas demonstrate that blanket peat did not deter the early miners but there is a discernible area in the southern half of the northern plateau bearing only short lengths of valley bottom tinning scattered more thinly though consistently across the surface. The Haytor block of moorland lives up to its reputation for modelling the gross patterns of the Moor on a small scale with a sequence of lengthy valley-floor works lying in line with the northern zone just identified. The density and distribution of

FIG 199. Streamworks: (left) the lower reach of Beckamoor looking towards Vixen Tor, below the centre skyline; (below left) the floor of the upper East Okement filled by tinners’ waste heaps.

streamworks is of course itself a commentary on the density and pattern of tin-bearing lodes within the granite.

These sites are immediately obvious to any observer walking across their terrain. The alluvial tin ground, as we find it now, tends to have outer boundaries that are themselves very steep little slopes a few metres high cut into the bottom of the valley side and representing the outer extremity of digging (Fig. 199). Within the ‘trench’ so defined there will often be a pattern or patterns of mounds each with a definite long axis, often so close together as to suggest that their upstream edges are overlapped by the next waste dump (the miners worked upstream to save covering unexplored ground with waste). Where the mounds lie across the general slope of the valley floor their shape in section depends upon their origin. When wheelbarrows were in use there is a distinctly gentler slope facing upstream, where they are symmetrical it would appear that only a Devon shovel (long handled, with a shield-shaped blade) was used to turn over the ground. Easily accessible good examples of streamworks are in the upper valleys of the Meavy and its headwaters upstream from the Burrator Reservoir forest and below the B3212 road from Princetwon to Yelverton; in Beckamoor Combe above and below the B3357 between Merrivale and Pork Hill, and in the whole length of the East Okement valley floor upstream from Cullever Steps. Hillside streamworks have similar patterns of spoil dumps but water-flow regulation demanded their secondary use as gradient determinants by their angle across the slope. The steeper the slope the nearer to the contour is the axis of the mound. In some cases short walls have been constructed to hold waste on the upstream side of the dump and prevent it from falling into new working ground – the opposite of the streamwork system. There is a particularly good example on the western flank of Cosdon where the tin ground is some 200 m long and 120 m wide, with parallel curvelinear mounds themselves more than 100 m long.

All these ‘cliffs’ and mounds offer a variation from the valley floor for plants and animals, they are better drained and provide some shelter on their leeward side, those who have time to wander among them may come across habitat microcosms not found on the more open moorland around the site. Stagshorn club moss Lycopodium clavatum clearly prefers the slopes of such mounds. Figure 200 shows the plant near Vitifer. There are some valley-floor tin grounds where

FIG 200. Stagshorn club moss on the slope of a tinners’ waste mound at Vitifer.

few if any dumps within the boundary ‘cliffs’ are apparent, as though little waste was generated or there was later infilling of the spaces between the mounds by waste flushed out from more work upstream.

Of the mines, the so-called openworks, or beamworks, have the greatest effect upon the moorland scene, though less extensively than the streamworks (Fig. 201). Openworks were essentially created by the quarrying of a tin-bearing lode within reach of the surface and as far as its extent lengthways and downwards could be dug by hand. It seems that openworks were already an extension of streamworks in the fifteenth century and had probably been superseded by adit and shaft mining by the early eighteenth. The result in the landscape is a deep, usually

FIG 201. Map of the openworks, more concentrated than their predecessor streamworks but still making a substantial impact on the surface (after Gerrard, 1997).

FIG 202. View from the B3212 across to Grimspound – openworks are carved into the nearer north end of Soussons Down, the col south of Headland Warren and below Grimspound. The ruins of the Ancient Tenement Walna are in the foreground.

narrow, cleft in the surface unrelated to natural features. Most are now V-shaped in section and thoroughly vegetated, though there are still weathered vertical rock faces in some instances. There is a very dense collection of openworks stretching from below Hookney Tor next door to Grimspound through the col above Headland Warren across a headstream of the West Webburn and on to the unforested summit of the Soussons Down ridge (Fig. 202). The collection includes vegetated V-shaped slots especially below Hookney and Birch Tors and rock-sided trenches up to 6 m in depth between Soussons plantation and the Warren House Inn. These are part of a very dense collection of tin-working landscape relics including leats and streamworks and many late-industrial details such as wheel-pits, building foundations for miners’ barracks, a blacksmith’s shop, miners’ walled enclosures for gardens or stock, associated eventually with the Birch Tor and Vitifer mines. The openworks’ successor shaft and adit mines were worked here into the twentieth century and there are photographs of work in progress. This complex of tin-working features is much visited because it is so near the B3212 and the Warren House Inn and because it forms such richly concentrated evidence of one of Dartmoor’s two long-time staple industries. It provides a more extensive set of variations on the moorland surface than a simple collection of waste dumps, and provides an oasis of shelter for plants and animals and a spectrum of drainage variation that suits a greater range of organisms than that available on the smooth, or rocky, slopes around it, untouched by digging. Until 2005, ring ousels made the site one of their strongholds, they are very attached to ruinous walls and rock faces, but their numbers have thinned all over the moor since then. Wheatears and redstarts actually use the walls and rocks for nesting. Willow warblers and reed buntings find the sallows around the leats and pools to their liking and it is rare not to see cuckoos there, though their hosts are the meadow pipits who share the heather and bracken of the openwork sides and the flats in between them with whinchats and skylarks. Robins, tits, wrens and blackbirds are in sufficient numbers to proclaim this an oasis in the moorland for them and a hint at human companions only recently departed.

There are two other kinds of mine and their spatial surface impact is fairly limited. The most elderly is the lode-back mine which consisted of a short vertical shaft to exploit the lode unreachable by opencast methods, and work persisted along the lode from the shaft bottom as long as it was safe, rather like the bell-pits of the smaller coal fields of the Welsh Border, but shaped in section more like the Duke of Wellington’s hat. Such shafts remain at the surface as funnel-shaped holes with waste dumps alongside them. They often occur in procession following a lode already identified, sometimes continuing the line of a streamwork, or an openwork. There are two parallel lines of such mines across the small abandoned fields just opposite the remaining inhabited cottages at Whiteworks south of Princetown, spectacularly seen from the air. They are distinguishable from prospecting pits by their size and shape, the latter are usually rectangular with a long axis across the presumed line of a lode. Finally there are true mines, whose shaft entrances and those of related adits are the only evidence at the surface of their existence. Where most of what has been described so far was indulged on Dartmoor from the Dark Ages onwards, the timing of the origins of shaft mining is still unclear. There are references to ‘underground’ working and the works of the ‘old men’ being rediscovered in newer mines in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. At Vitifer 13 shafts and three different levels are described at the end of the eighteenth century which implies considerable life before that. It was worked from then, even if intermittently, until the 1930s and accounts for the bulk of the complex of surface remains in that valley head. Its impact on the wider landscape is necessarily very limited but, as photographs from those 1930s show, at the time of the mines’ (to include Golden Dagger) peak performances the ancillary surface activity created an industrial scene to rival small sections of the Black Country. Shaft-head structures and large waterwheels protruded upwards where only church towers had ever done that before in the Dartmoor scene. We should accept that smoke and noise must have been a feature of even the smallest tin mine site from early mediaeval times on.

The performance of the whole industry through the period for which there are scattered records was variable. There was clearly a very high peak in the decade-and-a-half beginning with 1515 AD, and in 1523 the ‘coinage’ at 630,000 pounds (286,350 kg) weight, doubled the output of the best of the 65 years before that. (We have no figures before 1450 AD.) There was a considerable slump during the middle of the seventeenth century (Civil War and Commonwealth dampened all trade) with a slight recovery as tin production moved into the eighteenth with a peak of 125,000 pounds (56,800 kg) in 1706. That was still less than a fifth of the output of Henry VIII’s best year and only a half of the mean production figures for the fifteenth century. The last recorded Court of the Stannaries, which will be explained almost immediately, was held in 1786 at Moretonhampstead, when the boundaries of the stannaries were rehearsed. Stannary law, by which miners, their masters and their men had worked for 700 years or more was rendered effectively powerless in 1836 and abolished in 1896. The last tin was shipped from the Vitifer waste tips to South Wales in 1939 for smelting and it represented the end of an industry begun before the twelfth century.

Dartmoor’s socio-economic landscape had been divided for most of that time into four stannaries whose production was ‘coined’ at Ashburton, Chagford, Tavistock and Plympton. No tin could be sold until it had been through the

FIG 203. Crockern Tor close to the B3212, from the south. It is close to the conjunction of the four stannaries, and is where the tinners’ Great Parliament met.

coinage process. It was a combination of assay, marking and ‘duty’ collection. The tin was then often sold on the same day at the same place, so there was in effect a ‘tin market’ attached to those four towns. The four stannaries, named after the stannary towns, were required by a writ of 1198 AD to send jurors or jurates to a central court – often called since a Great Court or Parliament – which was held at Crockern Tor near Two Bridges, roughly equidistant from the four stannary towns (Fig. 203). The court was under the jurisdiction of the Lord Warden of the Stannaries, a post created in 1197 and first held by William de Wrotham. It still exists in the hierarchy of the Duchy of Cornwall, though of course all this was going on before the Duchy existed and was thus done then in the name of the King. The Court was to be chaired by the Lord Warden or his representative the vice-warden who was usually local. The writ of 1198 was issued by Richard I’s chief minister, Hubert Walter, to ‘declare the law and practice relating to the coinage’ which implies recognition of the need to clarify mining operation and administration for which no earlier written record has yet been discovered. The Great Court dealt with disputes between miners and between mine-owners, and more importantly reviewed the law to date and made presentments establishing new laws or revoking existing ones as was deemed necessary at the time.

It seems likely that the Normans, as they did in many other areas of social and economic activity, ‘tolerated and absorbed’ whatever Saxon systems existed in this respect, but now felt the need to crystallise them. From before Domesday until the sixteenth century, it was ‘lawful for every man to dig tin everywhere in the county where tin is found’ and only in 1574 did the tinners’ Great Court find it necessary to forbid miners to dig ‘in or under meadows, orchards, gardens, mansions, houses and their curtilages, arable land [defined as until two years since the last crop had been harvested] or to take more than twenty timber trees from any wood or coppice’. So, throughout the mediaeval period miners and their processes were very privileged, and their freedom to work ground must be a commentary on the value to society generally of metals in all their forms, prolonged of course by the taxable value of the output to the King. The corporate view may be philosophically sound, but as has always been the case, it does not necessarily help the individual in his own immediate circumstance deal with his difficulties with the privilege of the few. The 1574 ‘presentment’ had effectively confined new entrepreneurial tin working to moorland, where it had always been most intensive. We have already seen how that intensity has affected the moorland surface and produced many local variations in microclimate and habitat. The need for the organisation and regulation of tin working just summarised is in part explained by that intensity and thus a symptom of a nice relationship between the working men, their masters and their shared landscape.

Other metals

Ninety nine per cent of the mines in or on the granite are for tin, but around the metamorphic aureole and just into the fringes of the granite copper, lead, iron, arsenic and even silver have all been mined by shaft or adit. The landscape effect of this mining is not great. An isolated chimney stack at Ramsley above South Zeal represents the six copper mines that stretched in an arc from there to Bridestowe, there were six more, four on the west and southwest and two near Ashburton all without scenic impact now. Lead was worked in three mines between Mary Tavy and Bridestowe the southernmost of which, Wheal Betsy, has left to us the only Dartmoor example of the kind of tall engine house so familiar in the Cornish landscape not far to the west (Fig. 204). Wheal Betsy produced lead and silver from the late eighteenth century well into the nineteenth. Iron proper was only sought in two places, Smallacombe near Haytor and at Shaugh Prior, but into the twentieth century ‘shiny ore’ or micaceous haematite was worked at numerous small mines on the edges of the far east because it was an essential ingredient of rust-proofing paint. Kelly Mine near Lustleigh is a good and partly restored example of the scale of working in these later stages of the industry. South of Wheal Betsy the Wheal, or Devon, Friendship mine at Mary Tavy was the richest of those copper mines

FIG 203. Wheal Betsy, the only Cornish-type engine house on Dartmoor. It sits by the A386 as it rises out of Mary Tavy on to Blackdown; Cox Tor is on the right-hand skyline.

referred to above. It worked continuously from the late eighteenth century until 1925 (a longer history of continuous working than any other mine in the southwest peninsula) and reduced the Mary Tavy landscape to a real desert in that time. Arsenic, often alongside copper, was a lately valued mineral mined in the northwest and the southeast and up the Teign valley where, even later, barytes or ‘heavy spar’, a gangue (or ‘containing’) mineral thrown away earlier, was re-worked well into the twentieth century for a great range of modem uses from paper-filling and paint making, to barium meals to assist radiography. It is said that the Ramsley waste tips which contain arsenic, yield a path-clearing weedkiller to rival any garden centre offering of the twenty-first century. Fascinating though the story of this other-than-tin metal-mining is, bar the two structures and waste tips I have cited it does not contribute overtly to the landscape we find before us now, but, and especially in full, it is a proper part of Dartmoor’s whole economic history. That history is not over. It is proposed, as the first decade of the twenty-first century comes towards its end, to mine wolfram for tungsten production at Hemerdon Ball, the southernmost outpost of the industrial moorland about to be described. Planning permission to excavate a low percentage ore has existed for some time, but the world price has not justified working until now.

China clay

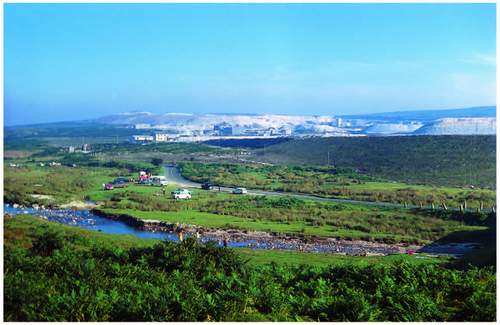

The other ancillary economic mineral of the granite pluton and its subsequent geologic history is kaolinite, and its extraction since the early nineteenth century has also yielded by-products such as building sand and brick-making material. Kaolin has been sought and briefly worked in the Erme and Avon moorland valleys, with small pits and waste heaps still evident at the sites (Fig. 205). The line of a railway from Redlake to Bittaford and erstwhile treatment buildings at Bittaford and Shipley Bridge are still standing as landscape memorials to the nineteenth-century effort. But at Lee and Shaugh Moors, stretching from Cholwich Town to Wotter, and inwards to Cadover Bridge and just beyond, the whole landscape is dominated by the symptoms of the extraction of china clay and its aftermath (Fig. 206). It has involved huge pits and waste tips (remodelled from the classic cones after the Aberfan disaster in South Wales), nineteenth-century industrial housing, leat and reservoir creation; road closure and diversion and ‘landscaping’ in the late twentieth century (Fig. 207). The whole area involved is a rough triangle nearly three miles across its base from Quick Bridge to Wotter, and two and a half miles from base to apex, Wotter to Cadover Bridge on the Plym. It can be overlooked well from the east at Shell Top and Penn Beacon, but there are significant viewpoints within the complex just bounded. There is more to the south: mica dams and treatment works (Fig. 208), well beyond the National Park

FIG 205. Aerial view of the southern plateau looking east from above Plym Head. The Redlake pit and its conical waste tip are on the left of the middle-ground and the Avon reservoir can be seen over the watershed beyond.

FIG 206. The Lee Moor clay workings of English China Clays in the 1960s: (above left) pit and associated ‘sand’ waste tip, the foreground and the road it carried then have long been excavated; (above right) the ancillary industrial landscape south of the pit also no longer a public view.

boundary but within the ‘Natural Area’ and, not before the moorland finally runs out, at Headon and Crown Hill Downs. Here is an industrial landscape to match any. Lee Moor and Wotter are, at their hearts, tiny china clay workmens’ villages with nineteenth-century back-to-back cottage rows or terraces, a Working Mens’ Institute, library and chapels. They shrink to nothing in the landscape compared with their raisons d’être, the vast spatial impact of the pits and tips. The three

FIG 207. The pits and tips of Watts, Blake and Bearne at the north end of the kaolinite deposit seen from above Cadover Bridge in the mid-1970s. The Plym runs across the foreground; its visitors not deterred by the background vista.

FIG 208. The waste slurry is captured in so-called mica dams downstream of the working site.

FIG 209. Shaugh Moor, archaeologically rich and now permanently saved from the waste deposition which came so close.

originally separate Whitehill Yeo, Lee Moor and Shaugh pits were amalgamated with planning permission in the last 35 years and their concomitant waste tips stretch to the west and the southeast of them with a smaller area of tip and mica dam at the Cadover Bridge apex. Here is a landscape white-out, bridging the boundary between moorland and farmland, bringing the granitic origin of Dartmoor to the surface in the most dramatic fashion, and spilling that geological influence into the valleys off the moorland. In 2000 AD it still provided work for a thousand people, though the world price of kaolin since then has changed that. The planning inquiry in 1971 that settled the pit-merging deal between two different operators, left applications to tip on the remainder of Shaugh Moor and in the Black-a-Brook valley alongside it (Areas ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ in the planning jargon of the time) to be settled later. In the late 1990s the clay companies made the magnanimous gesture to the landscape, and to archaeologists, of forgoing any potential tipping of waste on Shaugh Moor. There, as we have already seen, excavation has revealed much about Bronze Age developments on Dartmoor subsequent to the 1970s decision. So, there remains there a microcosm of Bronze Age detail of settlement and land boundaries. It is well worth examination by anyone intrigued by that first organisation of a land-use pattern to replace open moorland on Dartmoor, but who can ignore the pale grey surround (Fig. 209).

Just north of Cadover Bridge lie some pools in long-abandoned and small-scale china clay workings at Brisworthy, that are now clear and providing a habitat already listed in Chapter 6. The stronghold of the scarce blue-tailed damselfly is here and the species features strongly in the Dartmoor Biodiversity Action Plan, where the fear for natural colonisation of the pools ousting the damselfly is registered and close monitoring of change is proposed.

Stone quarries

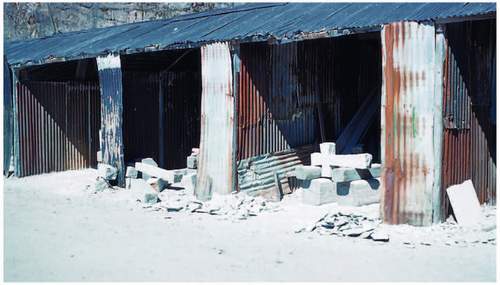

The quarrying of granite itself, of other rocks in the metamorphic aureole and even beyond it, is the last remaining landscape effect of men at work seeking mineral matter that remains to be considered. We have already concluded that with so much rock lying on the surface the need to quarry beneath it emerged very late in historic time. This has to be a consequence of demand, largely in the south east of England, for large quantities of building stone of handsome strength in sizeable blocks, and in short order, for largely public and national purposes in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Even the fourteenth-century parish churches of the Domesday manors, grand and towering though some of them are, appear to have been built with well-hewn moorstone. But when London Bridge and Nelson’s Column loom as market leaders there is suddenly a need for excavation on the grand scale (in its day) and the production of large blocks to architectural specification in quantity and on time. Quarrying granite, and effective transportation systems to get it off Dartmoor, are born. Despite that, quarries in the granite are few in number: Foggintor a mile and a half due west of Princetown, the Haytor complex and Merrivale on the Tavistock-Princetown road, remain the largest (Fig. 210). Each has had a specific public building recipe as its origin or sustaining influence:

FIG 210. Granite quarrying late in time: (above left) Merrivale Quarry below Staple Tor – still working in the mid-1970s – New Scotland Yard was clad with stone from here; (above right) Foggintor Quarry’s waste heaps – where Nelson’s Column was cut.

FIG 211. Points in the Haytor granite tramway as it runs down Haytor Down, to carry the blocks for London Bridge to the canal and estuary for Teignmouth. (DNPA)

Nelson’s Column, London Bridge and New Scotland Yard were the respective deals. The fact that the quasi-horizontal joints were wider apart as one descended into the granite, allowing bigger blocks to be raised and dressed was as good a reason as any for quarrying into the hill rather than searching for the block that would do, by wandering about the clitter. That, once started, the hole would yield a quantity of such blocks in one place was an obvious additional close advantage. Merrivale was on the turnpike to Tavistock, Foggintor a short distance on the contour from the same road, though soon nearer the Princetown-Plymouth railway line. Well-worked architectural building components, mullions and coping stones still lie there awaiting collection. A granite tramway was built from Haytor to the Stover canal which floated granite blocks on barges to Teignmouth via the Teign estuary (Fig. 211).

The tramway guided wooden-wheeled flatbed trucks partly horse-drawn and partly gravitationally propelled by a devious route down the eastern flank of the Moor still to be followed on foot as the Templer Way, named for the man who conceived the whole project, and who lived at Stover House between Bovey Tracey and Newton Abbot. None of these three major quarries is currently at work, though Merrivale only closed in the 1990s. It was working its own granite well into the 1970s with an extensive suite of cutting and polishing equipment alongside the hand-tool production of gravestones and farm rollers which it had

FIG 212. Inside the Merrivale complex in the 1960s – the domestic trade persisted alongside the large-scale contracts such as that for New Scotland Yard.

produced since it opened (Fig. 212). The men producing these locally needed artefacts in three-sided shelters with a wooden ‘anvil’ in the centre of the floor, always had small heaps of uranium ore at the back of the ‘shed’ to excite students and any other visitor who gained entry. Such was the investment in the finishing machinery at Merrivale by the splendidly named Anselm and Odling, that it went on importing a variety of exotic stones for just that – finishing – into the 1990s, and one can still pick up fragments of Norwegian gabbro, Italian marble and other exotic rocks alongside the track into the quarry.

There are a considerable number of smaller granite quarries scattered among the settlements round the edge of the great pluton, nearly all abandoned now. One of the larger ones is Blackingstone above Doccombe, close to Blackingstone Rock, one of the outermost tors of the granite, where a dark almost green-grey stone was worked intermittently right up until this century. The stone is common in Moretonhampstead buildings and alongside the A382. Almost due south of it is a quarry in the Wray valley side buried in woodland above East Wrey, which bears the same name, this time associated with Blackingstone Farm. Close to the Haytor Quarry already registered, there are additional, smaller pits, the biggest below Holwell Tor, and another just north of Saddle Tor. Near to Foggintor are quarries alongside Sweltor and Ingra Tor, both of which had easy access to the Princetown-Plymouth railway line that ran for some 75 years from 1878. Great Trowlesworthy Tor, in a very pink granite, was itself quarried and a half-finished millstone still lies there. There was of course a small quarry at the prison at Princetown and even smaller ones at Harford and below Western Beacon in the extreme south.

In contrast there is a welter of quarries all round the Dartmoor fringe in the metamorphic aureole and beyond, exploiting the virtues of various rocks. The biggest by far, and like the china clay pits still in production, is the large quarry complex at Meldon just southwest of Okehampton and south of the A30. For many years the quarry belonged to railway companies and their successors, and there is still a remnant of the old Southern Region line from Waterloo to Plymouth, now a branch line from Exeter to the quarry, carrying stone away for use as ballast on lines all over the southern part of Britain. Local demand for road metal is carried away by lorry. The main stone is Meldon Chert of Carboniferous age crushing to sharply angular fragments ideal for ‘road’ making of all kinds and visible in Figure 31. It turned out in the 1960s to be the only non-limestone rock to which British Rail had access in the south of England. Limestone is not the ideal railway ballast because of its water-retaining properties, hence the longevity of this quarry and the branch line to it. It is a major feature in the local landscape though more visible from outside the National Park than from the moorland. Between it and the Meldon dam are small abandoned quarries in ‘granulite’, one exposing a branched aplite dyke which runs with the chert from Sourton Tors for nearly 3 km east-northeastward.

Trusham Quarry in the east is the not as big as the Meldon complex. It is just against the National Park boundary at the near right angle it makes to leave the Teign valley and pass north of Bovey Tracey. It is also still working, extracting roadstone and aggregate for concrete block making from the dolerite. It is perhaps under half the size of Meldon but also more visible from outside the Park. Ryecroft Quarry two miles to the north and also adjacent to the boundary is out of use, as are a number of smaller pits upstream and on the shoulders of the valley at Christow Common, Scatter Rock and below Bridford in all of which Teign Chert and dolerite were worked. A recent application to modify the access to Ryecroft Quarry attracted much opposition and was refused in 2001.

On the southeast, alongside the A38 and inside the Park, Linhay Quarry in Devonian limestone is bigger than Trusham in area and also still working, though remarkably invisible from almost anywhere. Bulley Cleave and Higher Kiln quarries at Buckfastleigh (the former in Figure 29) are now long disused, though Bulley Cleave was working into the 1970s. Higher Kiln contains the entrances to the underground chambers whose collections of interglacial mammal remains and contemporary greater horseshoe bat colonies give it Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) status. They too exploited the Devonian limestone. The

FIG 213. Powder Mills near Postbridge; the highest of the deliberately isolated pairs of mills (with shared central waterwheel) all driven by the same leat is seen on the right. Sadly this ‘gun powder’ factory for the mining industry was built only ten years before the invention of dynamite.

Carboniferous limestone has also been worked just north and northeast of South Tawton, where defunct quarries are visible from the A30, and in which Bill Dearman demonstrated the intense folding that suggested a northward push by the Dartmoor granite pluton at the time of its emplacement within the country rock. At Drewsteignton, the same limestone was moved out of Blackaller Quarry right up until the 1990s. Around Tavistock a number of quarries worked until quite recently. Mostly they dealt in ‘Tavistock slate’, a dark green to black, coarse slate popularly used for facing parts of new dwellings to meet early planning design demands, sadly often looking like vertical crazy paving up chimneys. Some did exploit the dolerite intruded into the Carboniferous slates and shales and now exposed in a great swathe from Tavistock northeastward to Willsworthy, taking in Peter Tavy and Mary Tavy on the way.

Otherwise most tiny pits in the National Park were excavated for specific building projects, even single buildings, throughout the last three centuries. The odd one of them, at Yennadon near Dousland for instance, has persisted as a one-man, small-scale production site for retail stone – the kind of enterprise which the NPA, as planning authority, tolerates for its contribution to the detail of modern domestic development. Their impact on the landscape is minimal but exposes what lies beneath the surface and helps in interpreting it. The same historic principle of a quarry for a single project of course extends to the major civil engineering works of Dartmoor’s last century or so, primarily the reservoir dams. Avon, Burrator, Fernworthy, Trenchford and Venford all have attendant excavations solely for the purpose of immediate construction, now hidden from view or dwarfed by their structural successor. Meldon, obviously, had material already to hand.

Finally, it would be a blatant omission in this catalogue of excavation for construction in its widest sense, if reference was not made to the roadside pits which pepper the verges of the turnpikes across the moor, their companion roads on the fringes and the ‘tributary’ lanes of either (Fig. 214). The pits have usually been excavated on the horizontal from the road surface into the hill, though the quarry bottom has sometimes sagged; one or two still have vertical faces at their back ends but scree is quickly mounting them. Sadly their geological observational value disappears with that process, and sand martins are denied the low cliffs in which they sometimes nested. Even into the last quarter of the last century, as Chapter 2 tells, there were good exposures of periglacial solifluxion on Merripit Hill on the B3212, on the Cowsic-Black-a-Brook interfluve off the road alongside Long Plantation, where Beckamoor Combe abuts the B3257 and on the road to Moorlands Farm past Prince Hall. All, too, saved soil surveyors the labour

FIG 214. Roadside pit for extraction of gravel by commoners and tenants – one of many on the turnpikes alone, this one on Dunnabridge Common also housed sand martins until the 1980s.

of digging a sample pit. Their initial excavation was almost certainly associated with the road-making itself, their longevity was because Duchy tenants, and most commoners elsewhere, had the right or the privilege to take sand, gravel and stone for their own domestic use. In the 1960s a mini swing-shovel sat permanently in the pit above the bridge to Moorlands across the West Dart, such was the demand for rutted track repairs. These pits are in many ways the most obvious symptom of men at work among raw materials on the moorland surface to the road-bound traveller across Dartmoor. He may even be encouraged to park in them, for they hide the winking sunlit windscreen from many sides, or he may illicitly spend the night there in his camper van. They are also a reminder of the less common of common rights deployable on the moor, compared with the grazing right that is obvious all around. The right ‘in the soil’ to take stone and gravel, of turbary (to take turf or peat), of estovers (to take firewood and ferns for bedding) are all only for domestic use. Within the Forest, Duchy tenants join commoners in this corporate satisfying of need and so the pits also remind the thoughtful of the continued presence of benevolent landlords.

FARMERS, FARMING AND THE HISTORIC LANDSCAPE

The tinners’ dense and still obvious marking of the moorland is now all vegetated except for the standing remains of some buildings. We have just seen that even the roadside growan pits have few bare faces left. As abandonment happened new plant microhabitats were on offer and most of them available to grazing animals. Of course the whole spectrum of plant cover from wet to dry, on original smooth or rocky slope or on the new faces of waste heap and excavators’ ditch, has been grazed by stock and burnt by stockmen throughout the 5,000 years that tin ore has been sought, and farmers have farmed Dartmoor. That grazing and burning has created and sustained the vegetation mosaic already described, and over the years has demanded the development of that special set of skills that separates the moorland farmer from his lowland compatriot and sometime client. The clientele of history had two contributions to make to the hill-farmers’ economy through time – it bought hill-bred stock in the autumn to fatten and finish downslope and it sent, or brought, its own stock up to the hill for the summer to rest some of the lowland fields, make hay in others and allow yet more to be ploughed to grow winter feed and domestic crops. The annual process of transhumance, for that is what it was, came at a price to the lowlander. Dartmoor men kept a hill man’s eye on the lowland stock, reported failings and generally ensured that it thrived, its owners paid those men or their masters for the service and the privilege.

The pre-eminent landlord

The thirteenth – to sixteenth-century records of the Duchy of Cornwall, master of masters on central Dartmoor for nearly 700 years now, nicely demonstrate the business relationships involved then. The Duchy received a ‘three ha’pence fee’ per beast for summer grazing on the Forest in 1345 from its own agister. (Agisting is the allowing of stock to be grazed on, in this case, the Forest for a fee. ‘Agiste’ is an Anglo-Norman word meaning lodging.) The agister made his own percentage, and may also have paid others to perform or share his duties to the lowland stock. So the South Hams or mid-Devon cattleman paid more than the ‘penny-ha’penny’ per beast into the hill economy and in 1400 AD paid it for 10,500 ‘bovines’ to the Duchy’s agisters alone. That was the peak of agistment income in this late mediaeval period, numbers varied from 5,000 in 1290 AD to 6,500 in 1300, and fell back to 5,000 immediately after the Black Death (1348). Then it rose but from the 1400 climax there was a steady decline to 8,000 in 1500 AD. Harold Fox, who extracted these figures from the Duchy records, points out that these stock numbers are very large for their time and yet they are minimum grazing figures, for they are only for the Forest and perhaps the Duchy’s other commons, but therefore not even for the whole of the Commons of Devon, those which abut the Forest. Neither do they reveal figures for the manorial commons – those outside the Commons of Devon ring, animals not paid for, nor those of the Dartmoor farmers themselves grazing this and other moorland. Nor do they tell us anything about sheep.

That numbers rose so rapidly after the Black Death suggests that with many fewer mouths to be fed the demand for animal products – meat and leather especially – outstripped that for grain, which traditionally feeds the multitude. That of course would be a county-wide if not a country-wide phenomenon, but it points up here a substantial fourteenth-century shift towards livestock farming in Devon (never to be reversed), and the regard lowland Devon farmers then developed for Dartmoor moorland as a summer grazing resource despite their own general climatic advantage in grass growing. Though after all that, we should not ignore the fact that cattle numbers fell again through the fifteenth century and that may even hint at a diminution of grazing value after that peak of pressure in 1400. That is the first-ever suggestion of over-grazing on the moor, an accusatory claim that has been thrown at Dartmoor’s farmers at intervals right up to the latter part of the twentieth century.

Fox makes the further point that ‘three ha’pence’ was a paltry sum throughout this time compared with the value of the beast. An ox was worth ten shillings even in the middle of the thirteenth century, so probably more in the early 1400s. Oxen, whether for fattening and butchering or as beasts of burden and the drawing of ploughs, needed all-the-year-round feeding, so the summer bargain suited the lowland cattle men well. It was quite a good deal for Duchy tenants too, for they coincidentally paid the same figure per acre in rent (three ha’pence) for their in-bye land at this time. Other agisters, and of course the lords of the manor who owned the Commons of Devon or the parcels of manorial waste, their foremen, reeves and commoners, all had a slice of the action, overseeing lowland visiting stock alongside their own. A recipe for potential over-grazing at least in summer is easily perceived, and while Vancouver registered it again in the last decade of the eighteenth century on Widecombe Town Commons, it was only a summer event, the grazing was recorded as knee-high by the time the lowland cattle returned in May. What is seasonal over-grazing to one is balanced routine to another.

The Duchy of Cornwall was to all intents and purposes the lord of the manor of Lydford, in which parish the whole Forest lay until the 1980s when the Boundary Commission made it a parish of its own centred on Princetown. The Duchy also owned Bridestowe and Sourton, Okehampton Hamlets, Belstone, South Tawton and Peter Tavy Commons and, despite the dis-afforestation of 1204, Duchy officers claimed the right to drive stock off the other Commons of Devon when they thought it necessary at various times in the following centuries. So ‘lord and master’ fitted the Duchy well, and yet as an institution (invented by Edward III in 1337 to support the eldest son of the monarch when there was one) rather than just a family, its records are continuous and thus more valuable than those of other lords in investigating Dartmoor and its farming history. The chief officer of the Duchy, which persists even when there is no Duke, and when the net income all goes to the Exchequer, is still called the Secretary and Keeper of the Records.

The Ancient Tenements and other Duchy farms

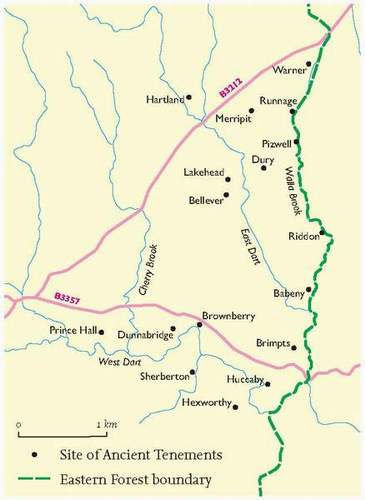

At the forefront of the kind of summer stock management we have just noted were the occupiers of the Ancient Tenements within the Forest, described first in Chapter 4, and of other farms against the moorland edge. Again we know more about the Ancient Tenements than the others because of the Duchy’s record keeping. They are all first mentioned between 1260 (Babeny and Pizwell) and 1560 (Brownberry) though ten of the 17 mediaeval sites are recorded in the first century of that 300-year span (Fig. 215). ‘Sites’, because there was almost always more than one farm holding at the named place. The record shows, as well as the three ha’pence an acre rent collected, tax paid for landless souls, presumably labourers or slaves, and a number of places ‘paying no rent’ in 1350, doubtless empty after the

FIG 215. Map of the Ancient Tenements (the modern roads are to aid location). The 17 sites accommodated 34 separate holdings at the peak of their occupation.

Black Death. The reference to Babeny and Pizwell in 1260 (predating the invention of the dukedom, but after the earldom had reverted to the crown), is because the men of those two places petitioned the Bishop of Exeter to allow them to use Widecombe church rather than trek all across the Moor to Lydford for their Sunday obligations and all their other spiritual needs, which traffic the Lych Way (through Bellever and Postbridge, Powder Mills and Willsworthy) still represents. Babeny and Pizwell are right against the eastern boundary of the Forest at either end of Riddon Ridge and the incident suggests that had the other Tenements in like position existed then they would have joined in the petition (Fig. 216).

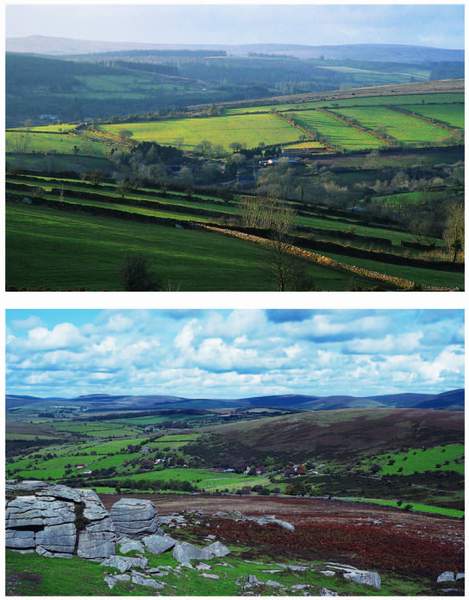

By extrapolation therefore we can see the first extension of the enclosed farmland landscape, since its Saxon consolidation in the Webburn valleys, up the West and East Dart and the Walla Brook from the mid-thirteenth century onwards. We know less about the origins of farms whose occupiers might also be regarded

FIG 216. The Ancient Tenement landscape: (left) the site of Babeny, its driftway to Riddon Ridge runs up the left-hand side of the middle-ground; (below left) the view from Yar Tor across Sherril, past Babeny and Riddon Ridge to the Warren House Inn (the white building near the central skyline) which sits just above the northernmost Tenement, Walna. Pizwell lies below it.

as likely overseers of summer visiting stock outside the Forest. But such ‘moormen’ almost certainly occupied sites like Teigncombe west of Chagford; Moortown at Gidleigh; Clannaborough near Throwleigh; Horndon in Mary Tavy; Moortown at Whitchurch; Stanlake above Burrator; Greenwell (mentioned in a pipe roll in 1181 AD) near Meavy; Cholwichtown and Yadsworthy in Cornwood; Skerraton in Dean Prior, Bowden near Cross Furzes; Fore Stoke at Holne; and Bagtor under Haytor. Those farms, as manors themselves or the manors in which they lie are all recorded in the century beginning in 1086, most in that year itself. Other Duchy tenancies, apart from the Ancient Tenements, like Yardworthy and Great Frenchbeer near Chagford, must also have played their part at some time in this upper end of the Devon version of a transhumance system, which Fox believed was well established before the eleventh century. All those ‘moormen’ were hill-farmers in their own right and traded their own crop of steers, calves, foals and lambs with the ‘finishers’ off the moor. That lower ground may not have been so far away. For while the base of any historic hill farm was a compact collection of fields yielding some hay, some oats or rye and some roots in a sensible rotation for home consumption and winter feed, there were within the Dart basin and close around the outer fringes of the moorland, mixed farms whose rough grazing was minimal but whose fattening potential was not to be dismissed.

The Ancient Tenements were largely copyhold (a copy of the lease was held by both the Duchy and the family) and succession was allowed for a financial consideration which was thus not far from freehold and thus from family security. While the farms grouped on sites like Babeny or Dunnabridge may have been individually occupied, the present field pattern suggests a degree of corporate activity almost certainly inherited from an open field-type operation. The written record shows that Dunnabridge was ‘assarted’, or taken from the Forest in 1305, by five men – one being Hamlin de Sherwell (now Sherrill?) – who paid 15 shillings between them as an entry ‘fine’ for taking in from the ‘King’s waste at Dunnabridge’ three ‘ferlings’ or 39 ha, and that they had 7.9 ha each. They paid seven shillings and sixpence for the first year’s rent of the whole and had to manure it all by the end of 1306, implying that it was by then ready for cultivation. The whole enterprise could only have been achieved corporately. The long, narrow fields closer to the farmstead at Babeny are similar to the ‘bundled’ strips that still offered fair shares of soil quality, slope and aspect to the then slightly freer farmers. Some of the narrow enclosures are now subdivisions of larger round-cornered outlines of still earlier newtakes and even bear personal names in the genitive to this day (‘Hicks’s Yonder’, ‘Hicks’s Homer’ and so on).

That reference to open fields inevitably drives us back in time. While the first 300 years of the Duchy record has given an insight into the latter part of the mediaeval working of Dartmoor’s highest hill farms and their communing within the core of the Park, we have to go back to the Domesday survey nearly two centuries earlier to set the baseline for farming the landscape outside the Forest. Then we shall see how, like the tinners, the farmers also left their physical marks on what we now see as moorland. The Domesday Book also gives us some idea of the stage the Saxon organisation of lower Dartmoor land use had reached before Harold messed up the defence of the realm.

The build-up to Domesday

Just as the Normans ‘tolerated and absorbed’ Saxon arrangements, patterns and doubtless labour (they became Anglicised; after all we don’t speak French!), so it is reasonable to suppose that the Saxons had been there before, though they may have enslaved Britons 500 years earlier in a somewhat less ‘tolerant’ mode. One step back, Fleming’s proposal reported in Chapter 3 that the 18 or so Bronze Age coaxial reave systems, scattered right round the moorland core as Figure 70 demonstrated, reflect what he calls ‘large terrains’ under at least corporate management, need not contradict the apparent distribution of Iron Age (British) settlement and farming. If the larger Bronze Age settlements fit strategically with the basal reaves then similar status may be applied to the Iron Age ‘forts’. The very short planning and construction time for the establishment of the reave systems implies authority, communal or ‘masterful’, and most likely large terrain by large terrain rather than because there was some central Dartmoor overview. Fleming also proposes putative common grazing above and below the enclosure systems altitudinally, or inside and outside in Dartmoor plan terms. He even suggests that the outer, ‘common’ grazing was used by ‘outsiders’ against whom the large terrain farmers needed a defence. So perhaps Dartmoor transhumance is that old. There is no reason yet discovered or archaeologically conceived, why the land-use reflection of such a negotiated, or at least defended, system shouldn’t have simply been picked up by the British of the Iron Age. They, folk and systems, seem to have survived through the Roman period and lay ready, even if only in a state of subsistence farming, for Saxon absorption. The large terrains were sometimes bigger sometimes smaller than their successor Saxon manors, and the Normans were probably not the first to bundle some manors into larger estates. The (probably remote) lord of such a bundle, as the Linehan quotation at the head of this chapter suggests, was probably less interested in how things actually worked on the ground than in whatever his or her dues were from those there, whether agents or farmers.

Thus, Fleming’s ideas allow the last prehistoric pattern of ‘land-holding’ to be slipped easily into the eleventh-century one through more than a thousand years, and we have already seen how the relics of those patterns still mark the mid-height moorland. His innermost and higher common grazing becomes the Saxon royal hunting forest extending outwards over the modern Commons of Devon, associated with the large terrains. The outer Bronze Age unenclosed grazing land becomes the Saxon, then Norman and finally the mediaeval manorial waste. Two principles: the valley system as the basis for more intensive land use organisation and the large terrain or ‘estate’ as the management division of that land use, had persisted, I will claim, for more than 2,000 years before William decided to have them described, assessed and valued. Some would say it persisted for nearly another 1,000 after that. Certainly the unique Domesday record demonstrates a Dartmoor Saxon pattern we can still recognise on the ground. Even the thirteenth-century consolidation of the Forest, the initiating of the Ancient Tenements and the information from the Duchy records only reflects that pattern, adds to it but doesn’t change it.

Dartmoor Domesday

For our purposes the record shows that 34 of Dartmoor’s present villages or small towns were manors in 1066, because each entry in 1086 refers back to the day when King Edward the Confessor was ‘alive and dead’, i.e. in January of that year (William, for obvious reasons, had no truck with Harold as ‘King’). Thirty-nine other manors are still on the map and nearly all their names remain the same, but they range from hamlets like Harbourneford, Dunstone and Sigford to single farms like Lowton in Moretonhampstead parish and Wringworthy near Peter Tavy. One or two names have to be traced forwards until they bear the modern name, a classic being Dewdons, a sizeable manor in 1086, whose name evolves into Jordan, southwest of Widecombe and by no means as sizeable, by 1724. A Jordan family had occupied parts of the hamlet in the seventeenth century during which the manor, long held by Hamlyns who also held Holne in 1086 (and remember Sherrill; Hamlyn is still a common name in southeast Dartmoor). Dewdons passed by marriage to Mallets from Somerset (Shepton Mallet?) at the end of the thirteenth century, was broken up and sold largely to adjoining holdings. But the exact moment of name-change of part of the original manor to Jordan is not yet discovered.