CHAPTER 8

Farming Dartmoor and Sustaining

Moorland: The Last Hundred Years

The main object of Dartmoor farming is to raise cattle, but not to fatten them. When they are of store age, that is from two to three years old, they are sold to graziers who have rich lands in the in-country, and are there fatted.

William Crossing, ‘The Farmer’ in The Dartmoor Worker, 1903

A large number of cattle and sheep are pastured on the Forest, remaining there from May until September. William Coaker of Runnage, who rents the east quarter, receives probably not less than 2000 head of cattle each season. John Edmonds of South Brent rents the south quarter, succeeding his father, a fine type of old moorman…‘Upright and down straight’.

From ‘The Moorman’, op. cit.

The Dartmoor of today which draws attention and affection is that of open commons, close grazed turf at the foot of a tor or side of a stream, pony herds, stone wall lined fields, sheep or cattle tracks weaving through grassland. This is the Dartmoor landscape that farmers create maintain and change…it is the farmers’ presence which under-pins Dartmoor’s economy, culture and vibrancy.

Richard Povall and Nancy Sinclair, Focus on Farmers, 2007

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THESE quotations lies partly in their dates, spanning the 100 years of this chapter. Crossing describes his own observations of a process or processes that are exactly the same as those rehearsed throughout Chapter 7 of this book and so 800 or more years old and still going strong when he wrote about them. His series of essays for the Western Morning News in 1903 in that sense underlined the well-tried suitability still of the farming that he saw for its Dartmoor context and for the maintenance of the moorland throughout that time. It had clearly persisted regardless of the economic and climatic fluctuations that Britain had witnessed from the twelfth century on. Moreover, he is writing less than a decade after the lowest point of the agricultural recession of the late nineteenth century and implying, by reference to longstanding practice and personalities then, that the farmers of this hill, at least, had survived that recession perhaps without noticing its devastation of the agricultural economy of England further east. Dartmoor’s longstanding socio-economic resilience had persisted into modern times, even though canning and maritime refrigeration, the first innovations to affect the domestic meat supply chain for centuries, were already in place when Crossing wrote. That resilience was at least partly based on survival, when necessary, by a low-input/low-output agricultural routine but with enough mixed farming flexibility in the group of small fields at the homestead to grow more corn when mean summer temperatures rose a little – as in the fourteenth century, or minimal cereal cropping in the Little Ice Age. The same principle is evident in the detail too, and can even be produced if we move forward another hundred years. There is still a Coaker at Runnage, an Ancient Tenement since at least 1317 AD, and his father was also still the agister for the East Quarter before the Forest became common in 1983. There is a successor John Edmonds at Gribblesdown in South Brent in 2008 who agists part of the South Quarter by virtue of a grazing tenancy from the Duchy. The resilience of the systems and of the landscape in which they work and which they sustain, has wrought a different, but equally strong, resilience in the people of this remarkable southwestern hill.

At this end of the 100 years, Runnage and the present Coaker family feature as one of three Dartmoor hill-farms and their incumbents in Focus on Farmers, a book produced by a contemporary group called Aune Head Arts based in Princetown. (The other two Dartmoor farms in the book are Frenchbeer in Chagford parish and Greenwell, already listed in the preceding chapter. Both, like Runnage, are on longstanding sites, Greenwell is mentioned in 1181 AD, Frenchbeer in 1346, both in pipe rolls.) The book is in part a reaction to the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak of 2001 and its aftermath, which hit the central basin and the northern fringe and called upon farmers’ resilience in a new way (Fig. 228). Artists of various disciplines, including writing, lived on the farms for at least six months and were exposed to all that modern hill-farming involves. The farmers, their wives and their children, bared their souls, and both of these exposures are documented in the book. Resilience, as a theme, is illustrated, but a new, and essential, flexibility also emerges as the twenty-first century begins. The remarkable revolution in communication throughout society in the 100 years in question has introduced aspirations to every family which the majority never imagined in all the preceding 1,000. Survival on a hill-farm in a depression because you could eat what you grew if your back was against the wall is probably

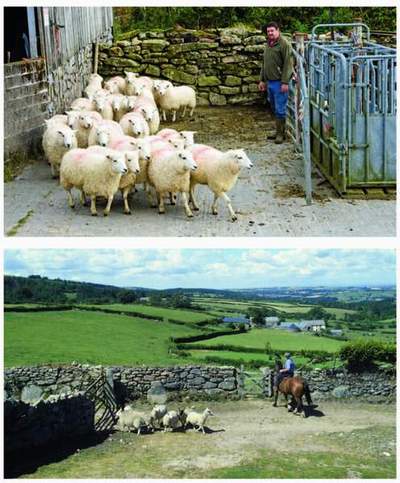

FIG 228. Moorland farmers about their business: (left) Phil Coaker at Runnage; (below left) Will Hutchings at Yardworthy. (Chris Chapman)

FIG 229. Yellowmead: just into the moorland edge there is still a collection of isolated farmsteads, many still occupied by those keeping stock against the economic odds.

no longer an option. But, as we shall see, the principle or at least its effect, may well be tested again quite soon. The farmer of a remote holding said in my hearing recently, ‘Yes, I could turn off the power, heat and cook with my own wood, and eat from what I breed and grow, but the family wouldn’t stay to share that way of life these days.’

INTRODUCTIONS AND THE QUESTION OF NUMBERS

Crossing, who is one of Dartmoor’s literary heroes primarily through his Guide to Dartmoor of 1909 – following Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes after almost 100 years – provides some other important information about the modern evolution of Dartmoor’s farming in that other Dartmoor Worker essay, ‘The Moorman’. Almost by chance he pinpoints the beginning of the most important changes in moorland grazing since mediaeval times when he records that Scotch blackface sheep were introduced to the Moor, appropriately by Mr Lamb of Prince Hall, in 1880 (Fig. 230). By the time Crossing wrote, Mr Lamb’s grandson had 1,000 head of the blackface sheep at Foxtor Farm and newtake and another 100 were on Walkhampton Common. Whether this indicates the rate of their spread in the new southern habitat is not clear, but if there were more by 1900, Crossing would

FIG 230. Scotch blackface ewes and a lamb on the raised bog at Challacombe.

FIG 231. A Galloway calf on Walkhampton Common – as Crossing said, ‘as rough and shaggy as young bears’.

have known if anyone did. Near the same time, Scottish black cattle were also brought in, and from Crossing’s description they were Galloways. ‘Beside our red Devons they look quite fierce and their calves are as rough and shaggy as young bears’ (Fig. 231). The dramatic significance of both these introductions is that they rang the death knell of the centuries’ old summer grazing routine on the commons and the Forest. Both the blackface and the Galloway could be out-wintered on the moor and lamb and calve out there, so two age-old parts of the system fell by the wayside. Letting grazing-with-care up here to farmers from the South Hams and mid-Devon from May to September would become untenable quite soon as available grazing was reduced by winter consumption; and the old legal principle of levancy and couchancy – not being able to graze on the common more than you could winter on your own in-bye land was blown. Grazing effects and its resulting patterns must have changed almost overnight. The old intense summer grazing had begun well after a long winter’s rest for the moorland vegetation and its spring re-growth, as demonstrated in that early nineteenth-century observation by Vancouver about knee-high grass on Widecombe Town Commons in May. Once all-year-round grazing began, the numbers of commoners’ sheep and cattle plus the in-country visitor herds of 1,000 summers would never be sustained again. The landlord’s ‘surplus’ (‘after the commoners are satisfied’ is the legal advice) had for centuries been quantified largely by his own decision, confirmed by his own court, which was peopled only by his own tenants. It, too, was obviously challenged by the new year-long grazing. His easiest income: from letting that surplus in the summer to in-country lowland stockmen, disappeared, and in many cases his personal interest in the management of his common disappeared with it. Slowly this led to the breakdown of the disciplines required to manage the commons properly and by 1950 only two manor courts were still held in the whole National Park and they rarely dealt with disciplinary matters. Soon after that enough commoners agreed that something had to be done if valued commoning was to survive, and that involved the reinstatement of discipline on all the commons. That led to the formation of the Dartmoor Commoners’ Association in 1954 as a federation of local associations, its evidence to the Royal Commission on Common Land which sat from 1955 to 1958, and eventually to the Dartmoor Commons Act of 1985 referred to in Chapter 1, of which more anon.

A classic illustration of the problems which had developed by the second half of the twentieth century, 50 years after Crossing wrote, is partly related to the beginning of political intervention in Dartmoor, and all other hills, from afar. The public, or at least governmental, decision to support farming from the early 1940s, onwards to sustain the food supply and keep it cheap, was effected in the hills through subsidies calculated per head of cattle and sheep kept. The incentive thus created led to a new and eventually vast increase in cattle and sheep kept on the common, some would say rivalling the numbers Vancouver had seen – but then they were only there in the summer. By the 1960s out-wintered stock, especially cattle, reached numbers that demanded the transporting of ‘feed’ out to them for lack of natural ‘keep’ (not, it should be noted, a historic right of common, which was to take in what was growing through the mouths of one’s stock). That meant the development of tractor tracks, cattle waiting close by all day for the next delivery and consequent poaching and damage to the vegetation which ironically was the ‘asset’ held in common (Fig. 232). Some commons’ edges had become simply the site of outdoor ‘sheds’ or yards, and the less energetic used the same feeding area day in day out. Commoners themselves began to differ about damage to the grazing, and some local associations nearly fell apart because of it. Devon County Council, as the then NPA, became involved in 1971 because of the perceived effect on the ‘natural beauty’ of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949 and even on that access. By 1990 attitudes would have changed enough for the new Commoners’ Council (see below) to make, without much debate, a regulation prohibiting any commoner from damaging or (significantly) allowing damage of

FIG 232. The effect of supplementary feeding of stock in winter. The picture was taken in the mid-1970s and the erosion of the roadside edge of the common is clear (see also Figure 179). By 1990, the practice had effectively ceased as the Commoners’ Council and management agreements both matured.

the natural beauty of the commons. This effectively ended the taking of hay or silage on to the common or causing damage by the use of vehicular transport. Tractors had been the real culprits but smaller four-wheel drive vehicles such as Landrovers were already commonplace as bale carriers. The commoners’ transport system continued to evolve however and within a decade quad-bikes had replaced many of the ponies which moorland farmers had until then habitually used to look at stock, and to drive it home and ‘out over’ again. Quad bikes represent the latest important innovation in moorland management with their virtues of lightness and ‘go-anywhere’ capability, thus reducing the need to make, and the incidental making of, new tracks (Fig. 233).

The general question of numbers of stock on the moor led almost inevitably to accusations of over-grazing from the 1960s onwards, and any observer could take one to a hard-bitten site. They were nearly always just inside cattle grids at the moorland edge and alongside roads. They thus involved short-cropped turf, ideal ironically, for picnicking and games for the burgeoning numbers of

FIG 234. Hemsworthy Gate below Rippon Tor, now a cattle grid whose gate is clearly visible. Short-cropped grass is close to the grid and round the signpost, but also extends up the slope on the common side of the newtake wall. Winter grazing is being conserved on the newtake side.

weekend and summer visitors (Fig. 234). But only a slightly more diligent search would reveal within a few hundred yards under-grazed vegetation, often rank and making for uncomfortable walking. Sheep and ponies are attracted to roadsides and stay close to them for long periods and for a variety of reasons, including visitors’ ill-advised offers of tit-bits (to ponies), the warmth of the road surface on summer nights (to sheep) and the salt-lick innocently provided by the highway authority in winter (to both). This all concentrates numbers near roads and car parking sites and partly explains the close-cropped vegetation seen by all passers-by, but the concentration was also a symptom of a shortage of time for traditional stockmanship or lack of experience of it. This latter because the headage payment tempted new and inappropriate stock, dairy cattle breeds for instance, on to the common according to rights registered but long unused. The perception for some observers was that many could not or did not spare the time to drive animals to lears further into the moor and away from entrances to the common and from the roads that cross them, even fewer could actually spend time learing stock having got them to the appropriate site.

Lears and stockmanship

‘Lear’ and its derivatives need explanation. It has the same root as ‘lair’, and learing is the Dartmoor equivalent of ‘hefting’ in the north. Well cared-for flocks of sheep have their own lear, graze in it and certainly return to it wherever grazing has taken them during the day, and lamb there so the next generation ‘know their lear’ from the start. Good shepherds, too, will speak of their own lears and recognise that those of other commoners adjoin theirs. They help each other, as being a commoner demands, by driving the straying ewe – or cow – back to, or at least towards, its rightful place. Part of the good management of a common is its division into enough lears which function well because they fit together in a mosaic without spare space. In effect the animals themselves maintain the lear pattern once it is firmly established. It is said that (in the old days!) a simple whistle would trigger the rapid return of ewes to their lears whether a dog appeared or not. Two other things flow from the principle. One is the clear virtue of selling established breeding flocks with the farm that holds the common rights, when it changes hands, because they ‘know their lear’. The other is the converse which is the effort involved in establishing a lear for sheep newly acquired from elsewhere. Sons and daughters, within our 100 years, given a new set of ewes to start a flock of their own, would be made to go out with the dog and sleep with them on the common to ensure their more rapid adherence to their lear.

Headage versus hectarage

The over-grazing argument was taken up by conservation ecologists, elsewhere as well as on Dartmoor, and steadily a head of steam was built up in a campaign to end headage payments and instead to subsidise, or compensate, hill-farmers according to the area of in-bye they occupied, and of the common grazings they used. A significant change, and a step towards that perceived Valhalla, was tested in the late 1980s via ‘management agreements’ and a shift from the 50-year-old social and production support in the hills began. The UK persuaded the EEC of the virtue of the experiment and by the mid-1990s Dartmoor farmers were being offered ‘contracts’ under various agri-environment schemes which paid for fixed stocking levels and annual grazing routines and compensated for stock withdrawn. Ironically, on the commons, rights unused for decades became a passport to compensation for not grazing by those who had not indulged it in any case, because grazing availability was the criterion, rather than actual use of it. It is still a matter of huge contention. Dartmoor became an Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) in 1993 under which such formulae were applied and its detail and effects are dealt with in the next chapter. However the ideal management system (involving stock units per hectare and annual grazing times) was still a theoretical one and the translation of it from a quasi-academic beginning to an agricultural practicality was to elude the innocent agents of government for some time yet. Fitting the simple matter of a seasonal and headage grazing limitation into the farmer’s business context – into a whole farm year, into the rest of the farm’s land, plant and buildings, and into the normal cycle of a suckler herd – seemed too difficult. Initially perhaps, out of innocence on both sides, the complete equation may not even have been considered. Most cattle withdrawn by the active grazier had nowhere else to go but market. Replacing them when initial grazing calculations were shown to be less than accurate was not a simple matter, for the disposal had had to lead to other economic initiatives if the books were to be balanced. Before these difficulties could be properly addressed, more changes were to be made in environmental and support systems at government and European level. But addressed they were, and the ‘Dartmoor Vision’ process, described in Chapter 5, which had been set in train by the NPA in 2003 was playing a substantial role in that by 2006. The effect of all this on the individual farmer’s income and expenditure account was to underline, and even to increase, the real significance and value of the public support which had been available since 1948 in one form or another in that account. But it also began the overt acceptance by the farmer himself that he had another role to play besides producing marketable stores for others to finish.

He no longer had to think of it as free ‘park-keeping’, now it was the management of a public asset or set of them for which there was a going rate. For all its initial blemishes the ESA process had the makings of achieving the best balance in the farmer’s perception of his new and his age-old roles. We will look at it all from the environmental viewpoint and in up-to-date detail very soon but it is necessary first to assess the farming situation that had developed within the National Park by the end of the 100 years in question.

THE FARMS AND THEIR BUSINESS

At the beginning of this century there are 1,300 holdings in the National Park but under a third of them are full-time farms, though that third does include nearly all the moorland ones. Just over half of those 425 farms are owner-occupied and the rest are tenanted. Some of the large terrain principles of the Bronze Age which evolved in socio-economic terms through the Dark and Middle Ages and into the eighteenth century are still there at the end of the last 100 years. The Duchy’s tenanted land, to make sense under my theoretical claim, would be interpreted as comprising more than one large terrain now. The Ancient Tenements probably count as four of them from north to south, centred on Postbridge, Dartmeet and Hexworthy, with another up the West Dart to Prince Hall. A fifth terrain lies south and east of Princetown, a sixth from Two Bridges northeast to Powder Mills, and finally an extensive one centred on Chagford Common. Outside the Duchy’s central core, at least five private single estates exist from north to south on the western fringe and almost abut each other. In the middle east, the Hambledon estate of the 1900s stretching from Drewsteignton south to Becka Falls, and the Whitley holdings from Houndtor to Ashburton, have both been broken up, the latter only in the last two decades of our 100 years. The Spitchwick/Holne Park estate still holds on.

The freehold farms average 63 ha in area and the tenancies 50 ha; but the range shows that only 10 per cent of all the farms are over 300 ha and two-thirds of the rest are under 100 ha. Nearly one in three of all the farmers now have some lower land outside the Park farmed in conjunction with that of their Dartmoor holding and it may form nearly a quarter of the land inside the boundary of the ‘business’. Many of the tenants in the Park actually own their in-country land, which gives them the added benefit of somewhere to go when their time in the tenancy ends and hopefully their children take over.

All the farmers are livestock producers and a little under two-thirds of them still regard stores as their primary end product, but nearly 40 per cent finish some animals somewhere, and in 2002 most thought that the proportion of fattened animals in their total output would increase, according to the answers to a questionnaire circulated on behalf of the NPA by the University of Exeter. They also expected the total numbers of sheep and cattle kept would be reduced, which does not bode well for the grazing regime needed to sustain the ideal moorland vegetation pattern. In fact cattle numbers (in the whole Park) had declined from 60,000 in 1972 to 53,000 in 2000, while sheep headage had risen from 151,000 to 240,000 over the same period. Cows and calves had peaked in 1985 and sheep in 1990, the latter just after the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) sheepmeat regime was put in place, but before agri-environment-scheme grazing formulae started to bite.

Just less than half the total number of full-time farms actually used the commons, though many more still have common rights attached to their hearths or to some fields. The stock numbers estimated as grazing the commons in the 1950s were only 2,000 cows and 13,000 ewes, by the mid-1960s they had risen to 5,000 and 40,000 respectively, and in 1996 20,000 cattle and 130,000 sheep were registered with the Commoners’ Council, reflecting the overall increases in the whole Park.

Since then, the livestock industry in general has suffered dramatic change, its Dartmoor component included – the cattle population ‘crash’ here was reported in Chapter 5. The overall change started with the attempt to curb beef mountains in Europe (associated with those dramatic increases in stock in the 1970s and 1980s just mentioned), then came the BSE scare that cut off UK exports to Europe. The foot-and-mouth Disease (FMD) epidemic of 2001, which saw outbreaks in the central basin of Dartmoor and on the northern edge (and especially the invidious contiguous culling policy that was deployed around it), seemed like a final blow. However, Bovine TB, though currently a dairyman’s problem, touches the hills in the end as all those other things have done. The hill-farmer produces stock to be finished by lowland men, so everything that affects them has a knock-on effect that ends up in his kitchen. Alongside all this the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, which finally disconnected support for farming from food production, has had massive effects upon farmers’ cash flow already, and in time, as currently planned, will reduce the actual amount of that support. That direct support is, in 2008, via a Hill Farm Allowance (HFA) – soon to disappear – and a Single (Farm) Payment (SP) which is paid per hectare farmed and has two rates above and below a ‘moorland line’ and a far greater one for all land outside the Severely Disadvantaged Area (SDA). Much hill grazing is inevitably above the moorland line, where the rate is nearly a sixth of that outside the SDA, with the added complication of shared rates for common land depending on the number of unit rights to graze registered on a particular common and the area of that common.

FIG 235. The arable component of the traditional homebase of the hill-farm was still evident throughout the eastern valleys until the 1970s. Hay Tor is in the background.

Given all that, it is perhaps understandable that the number of graziers has diminished and that the next generation in farm households wonders whether it is worth staying to do the job that was satisfying in grandfather’s day – or so he says. It also explains why under-grazing has overtaken over-grazing as the major management problem affecting the future of the Dartmoor moorland as a source of livelihoods, as a unique upland ecosystem, as a remarkably rich archaeological landscape and as the biggest public open space south of the Pennines in England.

Arable farming and dairying are now of little significance in the overall Dartmoor picture, though the former dominates patches of the fringe farmland, south of Buckfastleigh for instance. Small dairy farms had been widely scattered through the eastern half of the Park and down the narrow western fringe right up to the 1970s and their decaying milk-churn collection stands still punctuate hedge-banks near farm gates from Widecombe eastwards.

The farming population

Farmers and their spouses provide two-thirds of the whole workforce on Dartmoor farms, and a small proportion confesses to relying on unpaid help from other members of the family whose day job is elsewhere. Over half of the full-time farmers claimed to have at least one successor, which, given that the average age of all Dartmoor farmers is now nearing 60, is very important. The obverse side of that coin – the half that don’t have family successors – is a cause for concern in the context of retaining skills associated with the care of moorland stock, its deployment on the commons and the maintenance of the low-level vegetation mosaic. The same proportion of that farming family total – fathers, mothers, sons and daughters – have other agricultural work off their own farm. That can range from being a farm secretary to contracting out manual labour and driven machinery, but also includes technical things like scanning pregnant ewes and travelling long distances to provide such a service, and thus only possible if there is cover at home. ‘Diversification’, long extolled as the saving for farmers whose main business is no longer producing a good enough income, is widespread. Some is close to farming itself, commonly processing produce and selling direct to the public at the farm gate or in a farm shop or

FIG 236. Campsite backed by bunkhouse barns (here at Runnage Farm) doubles the workload but runs easily alongside the livestock farm routine. Income is supplemented as a new set of skills emerge in the farm household. (Christine Coaker)

farmers’ market, part-time contracting already mentioned, or using land and buildings for holiday accommodation of one kind or another (Fig. 236). These things can naturally combine to their mutual benefit because a full camp site provides a ready market for lamb chops, say – one purchase leading to barbecue smells, can have a snowball trading effect that persists beyond that evening. All of this increases the total household income, but a large number of farmers still claim that off-farm income is crucial to their whole-year results.

Current and future public support

Those results still involve receipt of the just-still-alive HFA, successor to the longstanding Hill Livestock Compensatory Allowance, itself having origins in the Hill Cow subsidy of the 1940s. Three-quarters of our farms receive HFA, and more than two-thirds of them were contracted under ESA schemes in 2002. The HFA is due to end in 2010 and its promised replacement is an Upland Entry Level scheme under Environmental Stewardship (the current umbrella for all agri-environment schemes now). It is interesting that a core support payment of long standing (and recognising the hardship in the hills) is ‘to be replaced’ by an agri-environmental one for which a farmer needs to earn points. ESA schemes will not be renewed after their present contracted term ends and in 2012 the SP (see above), introduced as a consolidation of previous core support systems in 2005, will be wholly based on area farmed in England, shrinking the while, and more of that below. One tenant farmer claims that in 2012 his SP will be less than the agricultural wage. So the confidence in a fair payment for the provision of public goods as part of the income and expenditure account that ESA establishment boosted in the 1990s and in the recognition by society that those goods in the hills are managed under severe difficulty compared with lowland, and especially arable farming, is already waning, as of course is the value of the public investment made since then. Indeed the potential waste of that investment for lack of its maintenance in the next decade or so is an underlying theme of the next chapter.

SHEEP, CATTLE AND PONIES

We have already seen something of the importance of the combination of the three major domestic grazers in sustaining the vegetation mosaic of the open moorland and the newtakes. For this record, cattle tear coarser grasses, especially purple moor grass in the spring, ponies bite heather and gorse but crop better grasses lower, and sheep almost mow the turf. Sheep also turn to heather and gorse in winter snows and new heather and gorse shoots for vital minerals in early summer. All play a significant and complementary role.

Scotch blackface ewes still dominate the sheep scene on the moorland proper but many are now put to rams intended to improve the quality of lambs. The ‘tupping’ is in October/November in in-bye fields and newtakes in the fortnight when the moor is cleared of sheep by Commoners’ Council regulation. ‘Entire’ male animals except stallions are excluded from the common by the same regulations. Dartmoor farmers will go to ram and bull sales as far away as Scotland and France almost as part of an annual routine. Many of the new rams are Texels of Dutch origin, but Germans are used and sometimes lighter French rams on first tupping of a hogget – or yearling ewe. The resulting ‘mules’ or cross-bred lambs are now commonplace and attempts to brand them, when finished, as ‘Dartmoor mules’ are being made (Fig. 237). Lambs are marketed from June onwards until the following March, so a variety of finished sizes are available to discerning butchers. Whiteface Dartmoor sheep, and a few Grey-faced ones, are still kept by those keen to keep older breeds going (Fig. 238). There are still some Welsh Mountain ewes in the northwest, and Exmoor Horns on Widecombe Town Commons and Haytor.

Galloways and their belted siblings (black or dun with a white band round the middle) are the commonest cattle across the whole high moor, but as with the sheep many cross-bred cows and calves also occur on lower slopes in an attempt to increase the size of carcass (Fig. 239). Welsh blacks, blue greys, Luings

FIG 238. Whiteface Dartmoor ewes – ‘prapper sheep’ to a devotee. Soussons Plantation is in the background.

FIG 239. A reminder of the South Devons and belted Galloways, but remember the Highland cattle in Figure 24 (see also Figs. 147, 227 and 231).

and some Highland cattle are still kept by their different devotees and there are a number of herds of South Devon cows lingering from the old transhumance days, many now wintered in sheds but out on the moor from spring to autumn. The Galloways and some Highlands, as might be expected, are the cows which penetrate furthest into the high plateaux in the summer and retreat to the mid-level slopes in the winter, while the other breeds and crosses are most likely to be seen from roads all year round.

Ponies are of two main types. The Dartmoor hill pony (Fig. 240), usually ‘coloured’ or carrying patches of different hues, is probably now the commonest, while the Dartmoor breed is always of a single colour usually bay, but greys are accepted. The latter are more often in newtakes and the in-bye than out on the common, and of course are bred in other locations in England now. There are pockets of Shetland ponies on Okehampton Hamlets Common and around Haytor. During our 100 years Shetlands were introduced first, in an attempt to reduce the Dartmoor indigenous ponies’ leg length to ‘improve’ them for the coal-mining market, and the Duke of Cornwall who was to become briefly Edward VIII, tried to redress the resulting ‘stunted’ mares by releasing Arab stallions on to the Forest in the 1920s. So the feral pony total herd is by now of

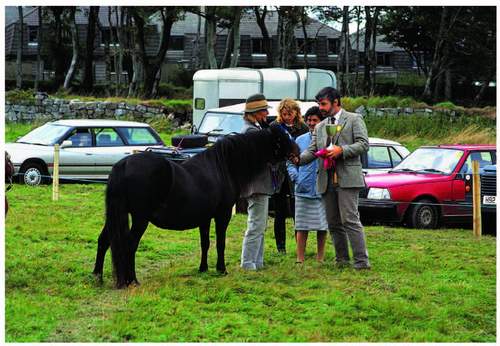

FIG 241. The Dartmoor Pony Show at Princetown in September, entry confined to the Dartmoor breed. The President, an ex-NPA Chief Officer, in attendance.

FIG 242. Chagford Pony Sales – a singular hill pony in the ring, September 2007.

mixed descent, and hence the enclosed or at least the protective grazing of the Dartmoor breed itself.

The moorland herd is difficult to count but it seems to have numbered some 1,200 in 2008 of which 200 were stallions, and 800 or so foals went through the autumn markets.

The Dartmoor Commoners’ Association’s evidence to the Royal Commission in 1956 had included what became known as the ‘Nine Point Plan’ to improve the husbandry of all the animals on the common. It consisted of i) the culling of old ewes; ii) the dipping of all hill sheep in the autumn; iii) the culling of old cows and any unthrifty cattle; iv) the weaning of calves at the proper time; v) the provision of fodder as conditions demanded; vi) the voluntary attestation of hill cattle; vii) making sure ponies bred on the moor were hardy; viii) proper feeding and watering of ponies in severe weather; and ix) limitation of stallion numbers. It clearly dealt with all three species, and part of it was triggered by the national publicity given to unhappy animals in hard winters, but it did mean that national attention was now drawn to the Dartmoor commoners’ corporate recognition of the need to put their own, shared house in order.

MORE ABOUT NUMBERS

The Royal Commission published its findings in 1958 and a research team was charged soon after with surveying the state of some commons in anticipation of legislation which it was hoped and expected would introduce management systems for common land. Among many others nationally, it surveyed the stock on Peter Tavy, Whitchurch and Walkhampton Commons on western Dartmoor and looked at one or two other commons such as Okehampton Hamlets and Holne. It visited the surveyed commons in March, June and October and found the grazing poor, sufficient and moderate at those three respective times. In June, on Peter Tavy and Whitchurch taken together it found 1,701 sheep of which Scotch Blackfaces were over 75 per cent, far less than half the 90 cows had calves and the 1,223 ewes had 478 lambs between them; 35 mares had 19 foals. It calculated that the average grazing density was some 3.5 livestock units per acre (0.4 ha) – a livestock unit then was one bovine or pony, or five sheep. In March, there were ‘many old ewes’ and nine dead ones were found. Friesians and Shorthorns were found among the expected hill-cattle breeds and hay was being fed near the road where severe poaching was seen.

Today, on Peter Tavy Common alone, 45 commoners are recorded in the Dartmoor Commoners’ Council register with rights to graze 9,104 sheep,

FIG 243. Looking up toward Peter Tavy Great Common from below Cox Tor; Roos Tor is on the right, Wedlake fields on the left.

1,527 cattle and 237 ponies – or 3,035 livestock units (a livestock unit now equals six sheep). But only 16 commoners actually turn out stock and they put only 624 livestock units on the common. The commoners have an ESA contract; their common carries parts of two separate SSSIs, and is partly within a military live firing range, involving clearance of stock on to that part of the common outside the range sometimes four times a week. Under the ESA scheme all cattle have to be withdrawn from the common from December until May, some from October to May. Sheep numbers have also been reduced, and the effect of both is that lears cannot be maintained. The reductions, combined with milder recent winters, means that considerable areas of rank and unpalatable grasses have developed.

There is thus a very confused picture of the common grazing situation over the last 50 years. The cattle and sheep numbers out on Peter Tavy Common now are still far greater than they were when those surveyors counted in the 1960s and reported over-grazed space, even though they are much reduced from the situation in the mid-1980s. But contemporary commoners see the effects of under-grazing all around them, and in their view there has been a massive deterioration of the quality of the vegetation since they took over from their fathers. It is worth noting that it was their grandfathers who attended the first meetings of the Dartmoor Commoners’ Association in 1953 and who were worried about the state of affairs on the commons then.

To a neutral observer it is clear that something had to be done about the headage on the commons at the end of the 1980s, but it looks as though the combined effect of disease mitigation, changes in support payments and official well-meaning but innocent regulation of numbers and seasonal timing has moved too far in the opposite direction. The optimal balance between a farm’s satisfactory economy, the common grazing’s place in that and the incentivisation of the maintenance of moorland vegetation in the interests of biodiversity, archaeology, the scene and access to it, clean water, and carbon storage in the peat is still to be worked out. The pursuit of the Dartmoor Vision should ultimately yield the formula that solves the equation if all parties remain committed to it. Then the potentially powerful alliance of farmers and agencies, represented by that shared and published Vision, has to sell the visionary equation to government and to the EEC, if the only labour force that can realise it is to remain available. Dartmoor has always been farmed, it never needed to keep its farmers contentedly at work more than it does now.