CHAPTER 9

The Contemporary Conservation

Scene: Its History and Its Future

A National Park may be defined, in application to Great Britain, as an extensive area of beautiful and relatively wild country in which for the nation’s benefit…the characteristic natural beauty is strictly preserved, access and facilities for public open-air enjoyment are amply provided, wild life and buildings and places of architectural and historic interest are suitably protected while established farming use is effectively maintained.

John Dower, May 1945

It must then be an essential purpose of National Park policy to harmonise man’s material needs with the protection of natural beauty.

Arthur Hobhouse, July 1947

As Duke of Cornwall I have had wonderful opportunities to get to know the Moor at all seasons and in all weathers…and to understand the high level of skill and care that is required from those who manage such a precious and finely balanced environment – to the benefit of all of us.

HRH the Prince of Wales, 2001

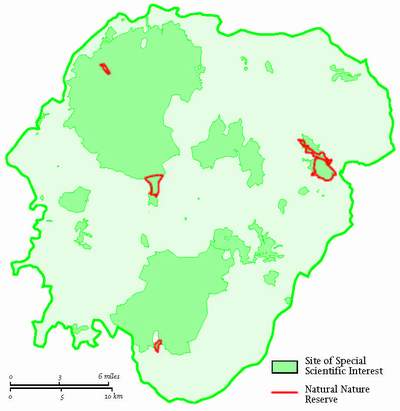

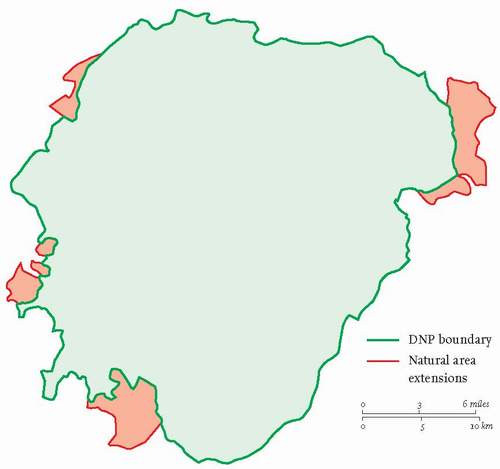

DARTMOOR, AS WE HAVE just seen, has been an Environmentally Sensitive Area for agricultural management purposes since 1993 but a national park since 1951. The National Park contains 48 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) covering about 26,150 ha; some have been there since 1952. It also includes three national nature reserves that are nearly as old (Fig. 244), and also carries more than one ‘candidate’ Special Area for Conservation status (SAC). SACs are a European Union designation under the ‘Natura 2000’ system. In Dartmoor they are those three big SSSIs and the Bovey Valley Natural Nature Reserves (NNRs). The National Park is itself some 99 per

cent of the Dartmoor Natural Area born out of the Joint Character Area family delineated for the whole of England’s landscape by the Countryside Agency and English Nature in 2005. That Area includes the whole Park and then the low hills just east of the north–south reach of the Teign and a strip from Trusham Quarry to Bovey Tracey to include the foot slopes of the far-east block – the only extensions on the east side of the Park. The china clay deposits of Lee Moor with Crownhill Down and the slopes southwards from there to Hemerdon Ball are included in the southwest. West Down, at the northern end of Roborough Down and the fields beyond it, Fernworthy Down north of Lydford and a triangle east of Bridestowe stretching up to Sourton are the only parts of the Natural Area outside the western boundary of the National Park (Fig. 245). This accumulation of designations and the space they take up tells its own story in quasi-political terms

both for Dartmoor’s landscape and natural history, and for the protective broth which increasing numbers of cooks have stirred in the last 50 or more years.

When the first New Naturalist volume about it was published in 1953, Dartmoor was simply a national park – with one slightly younger national nature reserve, Yarner Wood, declared in 1952 and low down just inside its eastern boundary, a wood not a moor. The National Park had been designated in the first group of nominated landscapes after the 1949 Act invented the designation, alongside the Lake District, the Peak District and Snowdonia in 1951. Still, in 2006, the man in the urban street, asked to name British national parks, remembers (or guesses!) ‘Dartmoor’ at least third and usually second in his list and can often only name three in any case. It was listed as a candidate from the moment the public discussion about British national parks began (Wordsworth having invented the idea when he said in the Guide to the Lakes, that that district should be a ‘kind of national property’). Dr (later Viscount) Addison reported in 1931, recommending the creation of British national parks to a government sadly swamped by a depression and a financial crisis. Lord Justice Scott reporting on post-war land use in rural areas in 1942, recommended the establishment of national parks and in the parliamentary debate of his report reference was made to creating them ‘in the first year of peace’. John Dower was then asked to study the question of establishing them and produced what is still regarded as the seminal work on the subject in May 1945, before that first year of peace had begun. He ends with the sentence: ‘There can be few national purposes which at so modest a cost offer so large a prospect of health-giving happiness for the people.’ He also said that further work was necessary and the government, only two months later so urgently was the prospect regarded, asked Sir Arthur Hobhouse to do that work, and he reported his results in July 1947. Dower (who was a member of Hobhouse’s Committee) had argued that his central ‘National Parks Authority’ should also control a system of national nature reserves, but the Hobhouse Committee thought otherwise and set up a Wildlife Conservation Special Committee under, the then, Dr Julian Huxley to examine a nature conservation system for the country as a whole separate from the national parks. It reported in the same year, recommending a national ‘Biological Service’ which should acquire and manage ‘national nature reserves’ even in national parks, but that the proposed National Parks Commission should be empowered to create other nature reserves within the parks which it considered would be necessary to conserve local breeding populations of wild animals.

Government accepted this strange separation of landscape and nature conservation and in the legislative foundation year of 1949 created a Nature Conservancy (i.e. ‘Biological Service’) by Royal Charter under a committee of the Privy Council, and a National Parks Commission, under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act. That Act, a veritable conservation compendium, contained the means with which to define and set up national parks in England and Wales and the tools which it was thought the Nature Conservancy and local authorities would need to protect and manage wildlife, habitat and geological sites throughout Great Britain. In that regard, it invented ‘areas (not then ‘sites’) of special scientific interest’ and local, but oddly not ‘national’, nature reserves. It also dealt with ‘areas of outstanding natural beauty’ (AONB), long-distance footpaths and surveys for definitive maps of rights of way, access agreements and access orders. Strangely it offered no positive connections between any of these things, though some negative ones: an SSSI was one ‘not being a nature reserve’ and an AONB one ‘not being a national park’. But it was a protection and access omnibus that offered various lines on, and degrees of ‘shading’ for, the ‘white land’ of the contemporary planning jargon. White land was to all intents and purposes ‘undeveloped countryside’ born out of the twin Acts of 1947 (Agriculture and Town and Country Planning) which had produced permanent and comprehensive public support and protection for agriculture on the one hand and an equally comprehensive regulatory system for the control of all the remaining use of land on the other.

From Scott, Dower and Hobhouse there was a clear message that (in Dowers’ words) ‘established farming use should be effectively maintained’ in national parks, and thus an explicit acknowledgement that farming contributed much of the beauty of the landscape of England and Wales. Whether the word ‘established’ implies either that farming better not change methodologically, or better not extend its then surface limits in national parks is open to conjecture. Clearly the tools of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 were meant to regulate change in spatial and design terms for the whole of the rest of the domestic economy. So in the innocence of the early post-war years a dilemma was created for national park overseers whoever they were to be. Farmers were to be trusted with the heritage and the rest were not. Those overseers had a potentially powerful tool called development control (popularly generalised as ‘planning’) to deal with the mistrusted majority and at that time no real means of ‘doing a deal’ with the few (the farmers) who could influence, benignly or otherwise, the great spread of the rural landscape. No one, not even the apparently far-sighted founding fathers of the landscape and wildlife conservation system, foresaw the potential of the combination of that ‘odd couple’: public subsidy and hydraulic power, for modifying field, hedge and moor, even less the likely demand for housing, and the revolution in recreation mounted by the explosion of private motorised mobility and a weekly televisual invitation to examine things natural.

NATIONAL PARK EVOLUTION

Nevertheless the national park system was inserted remarkably rapidly into the landscape of England and Wales. The National Parks Commission began work with energy and as early as 1951 had designated its first four parks, though not without some battles lost. The Peak District and the Lake District, without much local fuss, were given free-standing Joint and Special Planning Boards. Such boards were invented in the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 and recommended for application to national parks by Hobhouse, writing when that Act was still only a bill before parliament. However the burghers of northwest Wales, and of the three counties (the same number in the Lakes and even four in the Peak) overlapping the area designated, rose up and resisted the idea of such a board, saying that they could well care for Snowdonia without such elaboration. The Commission withdrew and oversight of the park was given to a joint, but only advisory, committee of the three county councils, leaving actual planning, development control and management decisions with each of them in its own space. That clearly risked inconsistency of decision, lack of uniform policy and thus of unity across the new national park.

No further attempt was made to create an independent body to plan and manage a national park in the 1950s and the Dartmoor National Park, designated at the end of the year of the Snowdonia debacle, was thus set to be ‘administered’ by a special committee of Devon County Council, though at least it was within one authority’s area. The committee inevitably had a majority of councillors of that one authority and the occupational hazard of being over-ruled by the County Council, most likely on substantial matters of policy. The officers reporting to that committee, planning, legal and financial, were effectively part time and hence easily distracted from the national park purpose. Whatever its status, each of the four national park boards or committees of 1951, and eventually each of the first ten, had a third of its members appointed by the Minister of Town and Country Planning of the day to represent the national interest. He or she actually appointed them to the boards, but the County Councils could accept, or not, his or her nominations.

All this is to create the background for the evolution of the system of public management of Dartmoor as a national park over the last 50 years. That evolution had three main phases. The first, ruled as already described, lasted for 23 years, until 1974; the second, with new structures, obligations, a budget and staff of its own, though still ‘of the County Council’, another 23 until 1997; and the third, under a fully independent authority, is still with us.

Within each of those phases were milestones, or at least landmarks. In the first they were almost all about land-use battles: three reservoir proposals, china clay and afforestation extensions and a 200 m-high television transmitting mast. The third potential reservoir, at Swincombe, was beaten off, the extension of plantations never materialised, but reservoirs in the Avon and West Okement valleys were built and the transmitter, high above Princetown, was agreed to by the casting vote of the chairman. Road improvement and the military presence were, to the close observers of the performance of the national park committee of the day, continual irritants. All of the developments listed, it must be noted, were designed to have outcomes, and provide for people, well beyond the boundaries of the National Park, and a countywide parent committee or its parent council were likely to place more weight on that fact than those attempting to protect a less material national interest. Even they, the latter, needed to take into consideration the fact that the 30,000 people who lived within the Park were bound to be beneficiaries of all or some of those outcomes, as the chairman who swung the vote on the BBC TV mast made clear.

Meanwhile, the need for a daily presence on the ground did become clear, if at least recreational management for the national park purpose was to mean anything. One full-time warden was appointed in 1961 and two more later in that decade, and they led a large number of voluntary wardens, especially at weekends. Their powers were to ‘help and advise the public’ and to enforce any bye-laws that might exist. At the same time one mobile information centre was acquired and placed seasonally in that roadside pit with the ‘buried’ tor in it (Chapter 2) at Two Bridges (where the scissor roads crossed). A short footpath led up the West Dart valley to Wistman’s Wood from outside the information centre, a situation that slightly perturbed the Nature Conservancy. By 1970, too, the County Planning Officer had been persuaded to dedicate the services of more than one of his officers to national park business, but all this in a time when expenditure on that business, whether wages, the making of a car park or the erection of a public lavatory, had to be agreed in Whitehall item by item.

Reformation and renaissance

But a revolution in this limited arrangement was on the way and the second phase about to begin. Government, no less, had recognised at last that public taste and mobility had changed and recreational use of the whole countryside had exploded in the 20 years since those high-minded days of 1949. In 1968 the National Parks Commission was wound up and replaced by a Countryside Commission. It had its predecessor’s responsibilities for national parks and indeed all of the 1949 Act powers, but a wider remit both to advise government and to implement an innovative experimental power for landscape and recreational management purposes throughout rural England and Wales. (A Scottish Countryside Commission had been established in 1967.) Within three years the Government asked the Commission to ‘take a fresh look’ at national parks and long-term policies for them and a committee under Lord Sandford was appointed to do just that. However, before it could report, a bill to reorganise local government came before Parliament, and the Director of the Countryside Commission (Reg Hookway, who also sat on the Sandford Committee) saw and seized an opportunity to improve the national park management situation beyond all recognition. His achievement was the first and fundamental change in the evolution of Dartmoor’s governance since 1951.

The Local Government Act of 1972 established a single National Park Committee for each park that was to be a ‘senior’ committee of the county council with the largest area of the park within its boundary, but having seats for other counties which overlapped the park. It would be the planning authority for the whole park and would appoint its own chief officer – the National Park Officer (NPO) named in the Act; both the appointment and the naming gave the arrangement an unprecedented strength in local government terms. The Act also required the national park committee to publish within three years of 1974 a National Park Plan setting out its policies, implementation intentions and expenditure. It was to be a management plan, not a ‘planning’ plan. In the debate on the relevant part of the 1972 Act ministers promised that central government would meet directly ‘the lion’s share’ of the expenditure of a national park committee. It turned out to be 75 per cent of the accepted bid for funds year-on-year, which also strengthened the committee’s hand in budgetary arguments within the county council. The national park case often ending with the line: ‘and you only have to find 25 per cent of the cost of this modest proposal, Mr Chairman!’

Imagine the change in Dartmoor’s prospects for real conservation management of its then 945 sq km landscape – suddenly there was a single-minded authority (the NPA) with its own officers and a budget. The new NPA set about its task with vigour, it met for the first time a year before vesting day – and advertised for and appointed its National Park Officer by October 1973, the first in the land. He was able to appoint many new colleagues before 1 April 1974, and so on that day the NPA hit the ground running.

Lord Sandford’s report was published in that same April, though the Government’s response to it took until January 1976 to emerge. It, Circular 4/76, deserves its place in the printed record of the history of landscape conservation. It broadly accepted the Committee’s recommendations, most importantly what has become known in the trade as the ‘Sandford principle’. It stated that where an irreconcilable conflict is revealed between the two statutory purposes for which a national park then existed (‘preservation’ of its natural beauty and the promotion of enjoyment of it) then the conservation purpose must prevail. The Committee had asked for it to be made clear in statute that public enjoyment of the parks must ‘leave their natural beauty unimpaired for the enjoyment of this and future generations’, and I quote it only because of the resonance it has with the definition of general ‘sustainability’ that became internationally agreed some 20 years later. The government forbore to put in hand legislation to that effect immediately, but in the Environment Act of 1995, which began the third phase of our history, it did turn the Sandford principle into a statutory duty not only for NPAs but for all public bodies whose work found them, however temporarily, within national parks. Similarly, in 1976, it agreed to regard the promotion by the NPA of the social and economic well being of its area as ‘an object of policy’, but not a third statutory purpose. With hindsight that was a blessing in disguise, for while most NPAs including Dartmoor pursued the object of policy with some energy as Hobhouse had determined, none then had to wrestle with the effect on the Sandford principle of having more than two purposes. (For the record, three purposes were accorded to the Broads Authority in 1988, and four to the Scottish NPAs in 2003. It still remains to be revealed whether in practice on the ground such complications really can be made to work and the landscape conservation record of the original ten NPAs repeated in higher mountains and on coastal flats given their added socio-economic responsibilities.)

By 1977 the first Dartmoor National Park Plan was published on time. Its Foreword ended with this:

The communities of people in the hills, however physically dispersed, are close knit. They and their individual members are vital to the national park, they manage the surface and make it a living healthy organism. Their well-being is a pre-requisite of the care they take of, and the part they play in the Park. The circulation system of their organism – the 560 miles of road and 460 miles of path – is also a critical network for the visitor and must be kept equally healthy, by the right pruning, maintenance and sensible growth.

The total resource which is Dartmoor goes well beyond the national park purpose. Indeed recreation is the latest, least tangible and most volatile function for the hills. Farmers, foresters, engineers, quarrymen and soldiers also use it for society’s benefit and to some recreational users each of them provides an additional fascination. The farmers carry on an essential service and are also asked to carry a huge responsibility to society for the management of the scene. The new concept which is the national park plan could be used to co-ordinate the activities of all users, in order to ensure the continuing optimum yield from this Dartmoor resource for all those who can benefit from it.

The Sandford Committee had asked for the involvement of landowners in the planning and management of the national park and for a power for the NPA to make management agreements with them. It was to take a few more years before the powers were forthcoming, but the writing was on the wall and explains some of the sentences just quoted.

The new NPA decided early that it needed to practice landscape and recreation management itself if it was to influence others to indulge in such things for the public benefit. To do that it needed to occupy land, enough to allow the right scale of practice and experiment, but not so much as to overstretch its labour force or its budget. The half of the park covered by farmland and buildings would be sustained by its occupiers, who might or might not be susceptible to advice or persuasion – but there were tools to help the process. Moorland and woodland offered most scope for active public enjoyment and were the landscape characteristics that made the Park different from its context. They also sheltered a unique biodiversity, though no one spoke in those terms then. They were where the NPA needed to produce tried-and-tested management action to demonstrate what was needed if national park principles were to be fulfilled.

NPA LAND

The neglect of much broad-leaved woodland in the park was, as in much of late twentieth-century England, very clear. Many estates had committed themselves to developing and maintaining conifer plantations under a dedication scheme that gave them tax advantage and grant aid as the woods developed and this had often involved the replacement of native woods (Chapter 4). The NPA recognised the need to demonstrate what could and should be done if the existing woodland

FIG 246. Wray Cleave Wood from Wheelbarrow Lane on the opposite side of the valley. More than one valley-side tor protrudes through its canopy and Pepperdon Mine house is at the far right. In the foreground is one of a set of curiously separate hills which occur along both sides of the Wray – part of the Sticklepath Fault zone.

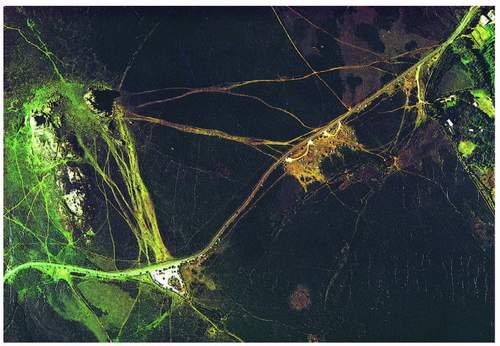

FIG 247. A vertical aerial image of Haytor Down taken in the early 1970s. The Widecombe road runs across from top right – the car parks, cars on verges and wide pathways to Haytor Rocks tell their own story. (DNPA after Brunsden)

resource was to be improved and sustained for all its potential values. It also accepted that conifer planting was an acceptable exercise within any one estate at the right scale if income from it could be applied to the costs of management of the broad-leaves. Its predecessor National Park Committee had been persuaded, only just before April 1974, to buy 74 acres (30 ha) of woodland in the Wray valley, Wray Cleave (Fig. 246), because a) the valley was described as a ‘major scenic wooded valley’ in the County Development Plan and b) the sale could risk further conversion to conifers already evident in the same valley. Eventually more plots on both sides of the River Wray – Sanduck, Huntingpark and Caseley Woods – were added to form a sort of eastern woodland collection.

As far as moorland was concerned, soon after the NPA took office Haytor Down came on the market. It straddled the B3387 from Bovey Tracey to Widecombe (Fig. 247). Here was the first open space, the first natural stopping place on the third most significant entrance road to the National Park in traffic terms (only those from Plymouth and past Ashburton carried more cars in the 1970s). Here also was Hay Tor, easily reached from the road on foot, easily climbed – the Victorians had cut steps in it so that their ladies could ascend to

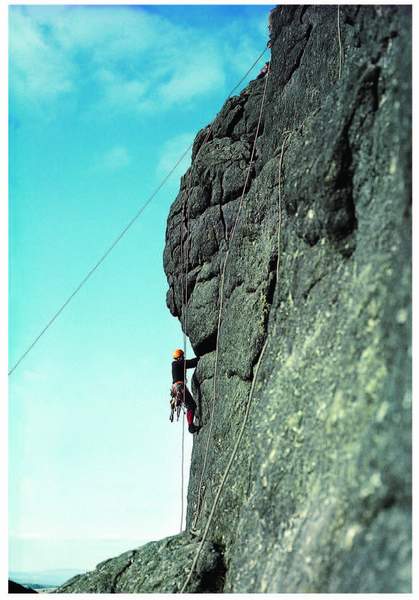

FIG 248. Dartmoor is not blessed with a welter of rock-climbing sites, but Hay Tor offers a number of potential pitches, often used by learners under supervision and military trainees – climbing congestion is commonplace. (DNPA)

take in the view…to seaward! This massive pile had a multiple attraction, its own intrigue for the sightseer, its educational demonstration of all the Dartmoor granite characteristics, and short climbs that challenged amateurs, soldiers and trainee professionals (Fig. 248). Haytor quarries and their granite tramway only added to these public virtues of the space. Most of these attributes have appeared in earlier pictures. Few bid at the auction and the NPA became the owner and thus a necessary new relative of the Haytor and Ilsington Commoners’ Association with the redoubtable Herbert Whitley in the chair (see Chapter 1).

In the same year a complementary move was made when the owner of Holne Common decided to move away and offered the moorland part of the common to the NPA. It, too, sat across a road, but this time a minor one chiefly notorious

FIG 249. Some of Holne Moor’s public benefits: (left) Combestone Tor from its inevitable car park; (below left) the view northwest from Combestone across the Ancient Tenement landscape from Bellever at the far right across to Sherberton, with a Dunnabridge Copse beyond – the skyline is the edge of the north plateau; (bottom left) the west edge of Holne Moor from a Huccaby field – Combestone Tor is on the extreme left of the skyline that runs up to Ryder’s Hill.

for being on the return half of a coach-drivers’ loop from Torquay to Dartmeet, where tea could be had. It thus functioned as the obligatory Torbay holiday-makers’ Dartmoor visit on a day too wet for the beach. Buckfast Abbey lay beyond Holne on the way back in case the moorland experience had itself been too dampening of the spirit. For some it was their first, maybe their only sampling of Dartmoor.

Holne Moor also had a tor, Combestone, even nearer the road than Hay Tor and level with it (Fig. 249). As a viewpoint it commands the central basin all the way to Princetown on the western rim, and overlooking in the foreground the landscape of six of the Forest’s Ancient Tenements. It thus also has its educational potential as an instructive viewing platform and as a rock outcrop. From it to the south runs a relatively short transect through the Dartmoor soil pattern set out in Chapter 3, from brown earth to the blanket bog on the plateau top, with their appropriate plant cover; to the north the same line runs rapidly downslope through woodland and clitter to the River Dart. It is altogether the pivotal point in a splendid Dartmoor profile. Since the acquisition of Holne Moor and partly because of it, as we have already seen, the common has become a veritable archaeological laboratory from Combestone eastward right across to Fore Stoke and spanning at least 2,000 years, from the Bronze Age to the end of the mediaeval period.

In the next year the same owner offered White Wood to the Authority who snapped it up. It was the remaining part of Holne common, which he had retained in 1975 to protect his fishing in the River Dart. Here was a rare chance to test the management of a commonable wood, almost unique now in Dartmoor terms. The wood is home to strong populations of wood warblers, redstarts and the pied flycatchers who have circumnavigated Dartmoor since the Yarner Wood entrapment already described in Chapter 5. Its own historical attributes, vegetation and easy access route, for people and foresters, were hinted at in Chapter 4, and the qualities of Bench Tor, overlooking it, in Chapter 2. Altogether it was a very appropriate purchase and the icing on this last slice of the cake was that with the wood came the Lordship of the Manor of Holne. The Manor Court was and is still functioning, one of only two alive in Dartmoor. The National Park Officer became steward of the Manor, and thus more embroiled with the homage – the collective noun for the commoners assembled now, originally for all the tenants of the manor – than on Haytor. The present record of the Court proceedings is kept in a book begun in 1790 when Sir Bourchier Wrey of Holne Park was lord of the manor and when changes in the ‘lives of the manor’ were registered at each session, their successors accepted or rejected and their dwellings or farmsteads assigned. Now the business is only about the common, but it, its management and that of its watercourses gives the NPO and, through him or her, the NPA a valuable insight into the detail of this 1,000-year-old labour. Two successive NPOs have proved good enough stewards to have had permanent marks erected on the Moor by the commoners on their departure, one a new bound-stone on the col between the Mardle and the Holy Brook, the other a new clapper bridge over the Aller Brook.

The NPA and the commoners

These two essays into moorland ownership and thus management proved invaluable to the young NPA, but because they both ventured into commoners’ territory that value was more than doubled; critically because a working relationship with the whole community of commoners in the National Park also began early. Almost as soon as the new NPA had taken office the chairman of the Dartmoor Commoners’ Association (DCA), the same Herbert Whitley who led the Haytor and Ilsington Association, came to the chairman of the NPA and said, in as many words, ‘You have the means to promote private legislation (through the County Council) and we need it.’ He explained that with the general demise of active lords of the manor as overseeing, benevolently or otherwise, their tenants as the sole graziers of their commons, discipline had largely disappeared and only a legally binding statute could correct the situation. The DCA, whose origins have already been described, had seen a national Commons Registration Act passed in 1965 with the promise of a second stage of legislation that would deal with the management of commons. (That second stage did not happen until 2006, so the Dartmoor commoners’ frustration of 1974 was justified.)

Thus began a partnership between the NPA and those commoners – the real managers of Dartmoor moorland – that still exists in 2009. It took 11 years, a defeat in the House of Commons in 1979 and many long and crowded meetings to achieve a Dartmoor Commons Act, known even nationally as the ‘1985 Act’, but still locally as ‘the Bill’ because for 11 long years it was just that. The NPA had responded positively and immediately to the DCA’s proposals in 1974, saying that what it needed were seats on whatever management body was sought and a public right of access to the commons in perpetuity which would be its responsibility. Devon County Council, to its everlasting credit, bore the financial brunt of the whole legal expeditions to Parliament, so the NPA’s annual budget was never unduly strained.

The ‘Act of’85’ created a Commoners’ Council to protect the interests of commoners, the status of the commons and to regulate their use. It was to be elected as to 20 of its members by the commoners who registered as electors and paid dues according to their quantifiable rights to graze and whether they used

FIG 250. Holne commoners clearing the leat to the Stoke farms. An old hay knife stuck in the ground on the left makes a good tool for shearing the leat sides. The homage foreman supervises and a then national park ranger, the late Mrs Dot Hills, is helping further down the leat, at the extreme left.

them or not. A duty was imposed on the Council to keep a ‘live’ register of actual graziers, and non-grazing right-holders who wished to vote for it. The elections were to be held in the historic quarters, each for five seats, one of which must be occupied by a ‘small’ grazier (with less than ten livestock units attached to his/her right). The NPA should appoint two members and two more to represent the private common landowners, and the Duchy of Cornwall would appoint one. The Council had to co-opt a vet and could co-opt up to two more individuals. The National Park Officer became honorary adviser to the Council. The NPA was empowered to make bye-laws to control public excesses should they arise out of a right to walk and ride on the commons, or liberties taken beyond those rights. The Council could make regulations to control the commoners’ exercise of grazing and burning, about animal welfare and to prevent abuse of the commons by those not entitled to graze. Both parties were to consult each other over the implementation of both powers and before any other actions relating to open moorland and its vegetation.

The Act was, for its time, as comprehensive as its promoters could make it, its few deficiencies were only revealed as those who had to implement it faced the changes that were to be imposed by national and international regulation, and in public support for agriculture as the twentieth century proceeded into the twenty-first. Its electoral machinery more closely resembled eighteenth-century hustings than modern polling stations. Its statement, for the ‘avoidance of doubt’, that the custom on Dartmoor was that the adjoining landowner should fence his land ‘against the common’ was not strong enough, while its prohibition of the severance of rights of common from the in-bye land to which they were attached (accidentally empowered by the 1965 Act) was ahead of its time. For a number of legal and financial matters the Council was given the powers of a local authority. Suffice it to say that Part III of the national Commons Act of 2006 is modelled on the Dartmoor Act.

There were some 1,500 Dartmoor commoners listed on the 1965 Act register, with rights on 104 Common Land (CL) Units belonging to 93 owners. One effect of the Dartmoor Bill’s passage was to speed up the Commons Commissioners’ hearing of disputes about land and rights that arose from the registration process. By 1985 they had declared 15 CL units void – for lack of commoners or non-grazing history – amalgamated some and reduced others in size. The 1985 Act records 32 commoners’ local associations in a Schedule and one, that for the Forest of Dartmoor, has been added to the list since its creation, though not for election purposes.

The ‘Forest’ was not a common prior to the 1965 Act but registered as such in 1967 and the Commons Commissioner sorted out, as far as he was able, who had rights upon it in a hearing in 1983. The Commoners’ Council decided in 1996 that those rights could not logically be regarded as historic and thus must be separate from any others held by the same commoner on other older commons. MAFF then accepted that decision for the purposes of paying grant under the ESA system for the better management of the commons. The separation of the Forest from other commons in this way is now disputed by MAFF’s partial successor, the Rural Payments Agency of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) which has recently decided that the Forest rights in most cases duplicate rights held on the ‘home’ commons of the grazier. It therefore discounts them in any calculation related to rights and common land area for the purposes of support payments. The situation has excited the European Union, which has difficulty understanding British common land in any case. In 2008 the matter was still in dispute, among others, between the commoners and the government.

Land management by agreement

DEFRA’s interest, apart from its responsibility for common land in law, arises out of payments to farmers for agri-environmental purposes which have existed for some 25 years or more in one form or another.

During the 1960s one of the effects of farming’s newer technical and financial power began to show, especially on Exmoor but on Dartmoor too. It involved the conversion of moorland by ploughing into ‘agricultural land’ – rough grazing being defined as other than farmland for some reason. In the Countryside Act of 1968 the Minister had taken powers to apply an order to any ‘moor and heath’ prohibiting its conversion by ploughing, but attempts to get such orders made came to little or nothing. In the same legislation the Nature Conservancy was empowered to agree, with the owner and occupier of any SSSI, the details of its management and to pay for that or carry it out, and to compensate for any restrictions that were part of the deal. However, progress was slow and while the most important tool so far devised for conserving habitat and landscape in the face of economic ambition began its gestation, the moorland ploughing process still proceeded. A campaign to protect moorland resulted in an inquiry into the problem on Exmoor. As a result, in 1978, Lord Porchester advised the government that the Exmoor NPA needed power, and a budget, to pay would-be converters of moorland compensation for profit forgone, based on an annual assessment of that profit by Exeter University’s Agricultural Economics department. The management agreement was born.

Pressure mounted for its application in all national parks from the Countryside Commission, and in 1979 the Ministry of Agriculture removed the need for farmers to get prior approval for grant-aided works ‘except in national parks’ where the farmer had to show that the NPA had no objection to the work in question. Thus almost by default a necessary dialogue between all farmers and NPAs was triggered for the first time. It was bound to include discussion of at least income forgone and the public value of the status quo, or even its improvement for the public purpose. Only two years later the Wildlife and Countryside Act gave to NPAs and the Nature Conservancy Council (revitalised and renamed by its own Act of 1973) powers to make management agreements with owners and occupiers of land. These management agreements became the building blocks of all the agri-environment schemes that have followed and spread from England and Wales to the whole of Europe.

In Dartmoor, management agreements became the order of the day in the NPA/farmer partnership. The first was made in the year of the enabling legislation and in ten years from then there were 56 covering 5,262 ha of land.

FIG 251. Management agreement land: (top) Babeny, the farmstead is left of centre with parallel hedge-banks to its right – the driftway to Riddon Ridge beyond it can be seen snaking away behind the farm. It is an Ancient Tenement and site of the first management agreement made by the NPA, and here with a tenant farmer; (above) Emsworthy, with Hay Tor beyond – the farmstead abandoned in the 1920s can be seen in the trees under the cloud shadow. At the head of the Becka Brook the land allowed access on foot from Haytor Down to Widecombe Town Commons, avoiding the road. A single sum bought a 21-year agreement with the owner-occupier.

They ranged from less than 0.5 ha at Spinsters Rock in Drewsteignton parish, which also ensured public access to the monument, to the 526 ha of Tor Royal Newtake, just south of Princetown, and the 1,662 ha of the Meavy catchment above Burrator. Some were for five years, with potential annual extensions after that – some were in perpetuity. More than half of them provided for public access. Tenant farmers were to be paid annually when money was involved and their landlord was entitled to a percentage, but owner-occupiers could be paid a single sum for, say, a 21-year agreement. Accepting the argument that the NPA could not predict a threat that might trigger management agreement negotiations when budgeting ahead of the year in question, a national sinking fund was set up by the Countryside Commission on which an NPA could draw for payments in the first year of an agreement. If, therefore, an agreement was struck with an owner within that year, the whole of the cost of the 21 years could be drawn from the sinking fund. Dartmoor used more than half the fund in each of its early years.

The Duchy of Cornwall and the NPA

By the 1980s too, another partnership had emerged, this time with the biggest landowner – the Duchy of Cornwall – and it also involved management agreements. The Duchy owned more than 28,000 ha including an enclosed block of the central basin and the heart of each of the high moorland plateaux. A new Secretary and Keeper of the Records, John Higgs, arrived at the head of the Duchy’s professional arm. He was a land-use academic from Oxford, just returned from the Food and Agriculture Organisation in Rome, and took the management of the Dartmoor Estate to a new level within the Duchy. It was, he claimed, never going to be a major contributor to the Duchy’s coffers so why not use it to demonstrate the environmental contribution that could be made by hill-farmers through the work of its tenants with the conservation agencies. His master concurred. John Higgs met the National Park Officer on his first visit to Dartmoor and a personal partnership also began. The NPA grasped this new opportunity and did much of the work that resulted in the ‘Future Management of the Dartmoor Estate’, a report to the Prince of Wales in 1983 that ran to more than 50 pages. Out of 19 ‘proper’ farms on the estate, ten had management agreements by the end of the 1980s, though not without some protracted negotiation, sucking of teeth and working out tricky formulae for calculating actual costs. To avoid a new fence across a large moorland newtake in shared tenancy, which was proposed to keep two herds apart at critical times in the cattle-keeping calendar, the calculation involved time for a stockman to police the herds, keep for his horse and for his dog for the whole of the critical period. The cost of maintenance of all

FIG 252. Huccaby Farm, in the centre, like Babeny a Duchy tenancy, just passed to the son of the tenant with whom the NPA made an agreement in the 1980s which allowed him to return to work alongside his parents.

the walls on an Ancient Tenement, continuing to make labour-intensive hay in far-too-small fields rather than take walls out, and grazing the newtake to a new seasonal timetable, added up to the wage for a man for a year. That allowed a son, ‘working away’, to return to the farm and prepare himself for the tenancy succession in the time-honoured way of slowly acquiring his parents’ stock and machinery. He is the farmer now. Thus arose the human and conservation satisfactions in the 1980s for landlord, tenant and for the new farmed landscape broker – the NPA (Fig. 252).

At another Ancient Tenement, where a proposal was received to divide the farm, ignoring the current field pattern, into a set of silage-making rotation blocks, a reorganisation of the proposed plan allowed existing walls to remain. The NPA’s survey of the fields revealed a hitherto unknown colony of greater butterfly orchids. The NPA alerted the Nature Conservancy Council, which, eventually, declared it an SSSI and took the four small meadows involved into a separate management agreement. The two bureaucracies were in great contrast as far as performance speed was concerned, but the story serves to introduce the second major player in the nature conservation game in Dartmoor in the second half of the twentieth century.

Nature conservation and the NPA

We have already seen that the functions of national parks and the statutory nature conservation system were born together in the same legislation in 1949, also that the Nature Conservancy had acquired three nature reserves within the national park in the 1950s. All three were woodland, Dendles Wood straddling the River Yealm two miles upstream from Cornwood, Yarner Wood clothing a broad blunt spur with a narrow valley on either side joining at the toe of the spur and forming Reddaford Water, a tributary of the Bovey, and the Bovey Valley Woodlands in the bottom of that valley. Yarner, the first to be acquired, is much the best known and the site of much research work almost from the beginning of its life as a National Nature Reserve, and well before the research arm of the Nature Conservancy was split off as the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. Clearings were created to encourage various butterfly species, notably the purple hairstreak; and experimental work on woodland management for nature conservation purposes began in earnest. Pied flycatchers, however, provided Yarner with its greatest claim to fame, and their story has already been told. Research there continues and, as recently as 2006, work by Dr David Stradling of the University of Exeter showed that ants in Yarner use the earth’s magnetic field to navigate. Suffice it so say here that Yarner Wood remains the premier Dartmoor base for Natural England, the contemporary successor of the Nature Conservancy of the 1950s whose officers established so much there.

The Nature Conservancy Council – of Great Britain – had been split between the three mainland countries in 1990 and thus English Nature had become the national nature conservation actor in Dartmoor from 1991 until 2006 when Natural England hit the streets incorporating English Nature, the bulk of the Countryside Agency (which had succeeded the Commission) and the Rural Development Service of DEFRA.

While nature reserves, dubbed ‘National’ long before that was a legitimate title, became early showcases and the home of pioneering field research, the designation of Sites of Special Scientific Interest also proceeded apace. By the mid-1960s there were 25, the biggest of which were two great expanses of moorland, one a rough triangle in the northwest with a base from Blackdown to Cut Hill and an apex near Okehampton Camp, and the other a broad swathe diagonally across the southern plateau, southwest to northeast from Shell Top to Holne Moor. Gidleigh Common, Blackslade Mire, Tor Royal Bog and High House Moor adjoining Dendles Wood were the other moorland SSSIs. Nine others were woods including the 200 ha of Holne Chase and Piles Copse, the only one of the three high-level oakwoods which did not have ‘Forest Nature

Reserve’ status (then in the gift of the Forestry Commission). The newtake in which Wistman’s Wood sits was declared an SSSI to buffer the wood and accommodate its (then suspected) natural expansion, which, as we now know, has actually continued throughout the last 100 years. This suite of sites of secondary protection also included five designated at least in part for their geological importance. Meldon Quarry and its tiny neighbour Meldon Aplite Quarry, the big one working, the little one long abandoned, and Haytor and Smallacombe Iron Mines are all in the metamorphic aureole. Lydford Gorge and Buckfastleigh Caves are beyond it. The former was declared as much for its damp, shaded habitat for lower plants as for its impressive geomorphology – by far the most spectacular gorge in the National Park, and outside the granite/aureole complex. Buckfastleigh Caves too had a combination of reasons for designation. Their complexity as a subterranean limestone system in a landscape floored by predominantly acidic rocks might have been reason itself. That they hold interglacial deposits containing a rich mammalian fossil fauna making, inter alia, a major contribution to the interpretation of the history of the middle reaches of the Dart valley has to be even more important. It was detailed in Chapter 2. The presence of winter populations of greater horseshoe bats, with their ‘lesser’ cousins also around, is the icing on the SSSI cake and another subject of detailed research (Fig. 253).

Almost inevitably the nature conservation designatory system has been applied ever more intensively as the last 50 years have proceeded. New knowledge of risk and rarity, more careful searching and the growth of public interest in things natural have all played a part in that expansion. The system itself has been refined, more powers to support it have been developed and the overview of the protection of wildlife and habitat has become European and even more widely international. The UK, along with many other governments, signed the International Biodiversity Convention demanded by the Earth Summit of 1992, out of which Biodiversity Action Plans for both species and habitats were born. The European Union created new designations, notably the SACs (coupled with existing Special Protection Areas – for birds) under the banner of ‘Natura 2000’ in the mid-1990s. The government published the UK Biodiversity Action Plan in 1994 and demanded a new appraisal of the biological and surface geological resource at local level as building blocks for the national contribution to the international action demanded by the Earth Summit. In 1997 the NPA and English Nature had published, in response to the UK Action Plan, their shared appraisal of Dartmoor’s natural history, ‘The Nature of Dartmoor – a biodiversity profile’. By 2001 the NPA produced its biodiversity action plan, ‘Action for Wildlife’, alongside a second edition of the profile

The original five geological SSSIs had meanwhile grown to 21, now including the sites of important pollen and charcoal profiles in the peat at Blacklane and

FIG 254. The corner of Whitchurch Down protected for its Irish lady’s tresses in the 1970s.

FIG 255. Dunsford Wood alongside the Teign. Innocent despoilers were finally persuaded by a campaign by nature reserve managers and local lady volunteer wardens to leave daffodils to their pollination, bee-feeding and for others to enjoy. The Devon Wildlife Trust still occupies the reserve but now as a tenant of the National Trust.

Black Ridge which were described in Chapter 3. The exposure of the actual contact margin of the granite in Burrator Quarry and the migmatite boulders and outcrops on Leusdon Common south of Widecombe are also designated. Extensive periglacial features around and northwestward of Merrivale, including Cox Tor, now constitute the most significant geomorphological site in the National Park that is specially protected. Woodland sites have increased to 17 in number and cover 2,378 ha. The two moorland plateaux are now totally of SSSI status, called North and South Dartmoor respectively, and East Dartmoor covers 2,000 or more hectares centred on Bush Down straddling the B3212, which all agree is the most significant stand of ling in the National Park. Blackslade Mire and Tor Royal Bog still stand alone, and with Okehampton Park flushes complete the ‘wet moorland’ suite. Five hectares of Whitchurch Down east of Tavistock protect a small stand of Irish lady’s tresses (Fig. 254), and Lydford Railway Pools, at 1.3 ha the smallest protected wildlife site in the park, support the fairy shrimp. There is little of the River Dart and its headwaters that is not within an SSSI, and the Bovey, the Lyd, the Okements, Tavy, Teign and Walkham all have reaches within SSSIs.

Some of these nationally protected sites are actually owned or occupied by bodies dedicated to conservation of nature or landscape. The Devon Wildlife Trust has occupied Dunsford Wood and the ‘Dart Valley Woods’ since the early 1960s, and in the former conducted a successful campaign to stop the quasi-commercial picking of wild daffodils before that decade was out. The Trust brokered a deal between the then Society for the Protection of Nature Reserves and the Devon Speleological Society which involved itself taking a lease of the Buckfastleigh Caves from the former and sub-letting part of the quarry floor and the caves to the latter. It also has two tiny woodland reserves, at Mill Bottom almost in Lustleigh village and Lady’s Wood southwest of South Brent. They were the first reserves it ever acquired and both carry a significant dormouse population. The Dartmoor Preservation Association owns High House Moor adjoining Dendles Wood, now within the South Dartmoor SSSI, and carries out a long-term bracken control experiment there.

THE NATIONAL TRUST AND THE NATIONAL PARK

The National Trust owns the major part of Shaugh Prior Commons, a block which comprises the southeast side of the valley of the moorland River Plym above Cadover, all the way up to the watershed from Shell Top through Broad Rock to Plym Head. This extensive moorland landscape includes Great Trowlesworthy Tor, with that distinctively pink felspar in its granite blocks, Trowlesworthy Warren, Willings Walls Warren and Hentor Warren, companions to the warrens described in Chapter 7. The Trust owns other significant properties in the National Park. The best known is the Castle Drogo estate in Drewsteignton parish, despite its reference back to a Domesday tenant, the castle was built by Julius Drewe at the beginning of the last century, and is regarded as one of Edward Lutyens’s unfinished masterpieces (see Fig. 57). Standing on a spur-end overlooking the Teign valley opposite Chagford, the castle is at one end of an estate that runs down both sides of the Teign valley to beyond Fingle Bridge. The south side of the valley is almost completely wooded, but the north side is open, bracken and scrub-covered, but very steep. The Huntsman’s Path takes the walker out from Drogo along the lip of the valley side and the Fisherman’s Path brings him back along the river’s edge after a descent to Fingle Bridge. Whiddon Deer Park, exactly opposite the castle, has already been named and also comprises much open space and its higher slopes boast small fragments of the 210 m Calabrian shoreline carved at the beginning of the Pleistocene (Fig. 256).

The Parke estate abutting the boundary of the National Park outside Bovey Tracey is both the Dartmoor office of the National Trust and the headquarters of the National Park Authority. The house is a small (by NT standards) four-square early-nineteenth-century building with the Egyptian embellishments – entrance columns with no bases and parapet rising in steps to the centre of the front, all

FIG 256. Whiddon Deer Park, part of the Castle Drogo estate of the National Trust and well known by lichenologists (see also Figures 69, 114, 123 and 276).

tomb-like – made fashionable by Napoleon’s (and Nelson’s) eastern Mediterranean campaign and also visible at other big Trust houses in Devon such as Arlington Court and Saltram. Adjoining and behind it is a wing of older buildings which form two sides of a courtyard and themselves link with an even older farmstead. The NPA and the National Trust occupy all of this as offices and stores and a spacious room, large enough for the authority’s formal meetings with the public present, has been built in what was the yard of the farmstead. The parkland of scattered big trees in a neutral and patchily damp grassland is the valuable part of the site in our terms – with moonwort Botrychium lunaria and adder’s tongue Ranunculus ophioglossifolius among the grasses (Fig. 114). It comprises a substantial parcel of the floodplain of the River Bovey and a gently sloping spur into the side of which the buildings just described have been inserted. Upstream of the house the valley floor is flanked by woodland on steeper slopes. The former railway line from Newton Abbot to Moretonhampstead flanks the estate throughout its length offering easy walking and cycling from a lay-by on the A382. The Trust also owns Dunsford and Cod Woods near Steps Bridge, Holne Woods downstream of White Wood below Holne Moor and Hembury Woods above Buckfast. All three are SSSIs or parts of the same. At Sticklepath, included in the Park at the 1991 review of the boundary, is a workable – and thus for visitors working – iron foundry and knap mill. The Finch Foundry uses the available power of the River Taw as it leaves Belstone Cleave. The Trust acquired it in the 1980s soon after it ceased trading.

So, in one way the National Park Authority has a number of important and strong allies in its effort to conserve quality in the landscape and all that underpins that. Some are more powerful than others, and that power lies in legislative duty but also in both membership and funds. While Natural England designates land and occupies some to fulfil its own functions, it also makes enforceable contracts with many an owner and occupier and even commoners, to try to achieve a wider spread of ‘favourable conditions for conservation’ – to use its own language. English Heritage does much the same and via the Dartmoor Vision has done a deal about grazing levels with the other agencies and the commoners specifically geared to the visibility of ancient monuments. The Environment Agency, in monitoring river and stream quality, promoting and protecting fish stocks and overseeing pollution risk on farms as well as in streams, plays another significant part in the maintenance of a healthy Dartmoor. Like Natural England it has a set of interesting antecedents the Devon River Board spawned the Devon River Authority to be absorbed by the National Rivers Authority – with the best logo a conservation body ever had – which then got lost in the great monolith we now live with. When every river had a water bailiff they were all honorary wardens of the National Park, as Rangers of the NPA were honorary bailiffs. The former were not expected to pick up litter, the latter had no power of arrest so did not nab poachers, but the increase in pairs of eyes watching each others’ areas of responsibility was to everyone’s advantage. The other side of this ‘allies’ coin is of course the number of cooks actually in the kitchen and whether the broth is stirred too much for the peace of mind of observers and land managers who produced the ingredients in the first place.

OTHER POTENTIAL CONSERVATORS

There are even more – cooks, that is. The County Council has five smallholdings in the National Park still and the Royal Agricultural Society of England owns a small farm at Stowford near Ivybridge. The South West Lakes Trust, a creature of South West Water, owns the catchment of the Meavy, the Ministry of Defence (MOD, and see below) owns Willsworthy Common (Fig. 257), whose commoners were bought out in the first decade of the twentieth century by its predecessor, the War Office. Both licence grazing now, and both have public consciences that a wise National Park Authority can prick if it so chooses. The MOD leases its Okehampton and Merrivale ranges from the

FIG 257. Willsworthy ranges with Hare Tor beyond; the only MOD freehold, the commoners were bought out by the War Office in the 1900s – grazing is now by licence. The NPA’s long-time chief planner, Keith Bungay, is approaching from the northeast.

FIG 258. Members and officers of the NPA inspecting a new shell-hole in 1981 about which complaints had been made about the scene and the hazard. The licence to fire shells technically required the prompt filling in of craters, not a happy pause in battle practice. Artillery firing ceased in 1996.

Duchy of Cornwall, and has licenses on South West Lakes Trust and Maristow Estate land to the south, both for ‘dry’ training, i.e. without live ammunition (Fig. 258). Substantial areas of common land are owned by South West Water on Holne Moor and Brent Moor, and by an electricity company on Blackdown at Mary Tavy, where a small but active hydroelectric power generation plant still exists. They also offer persuading opportunities to conservation authorities, as do the plantations in the Teign valley and around the Trenchford Reservoir complex. The Forestry Commission still occupies the three highest plantations described in Chapter 4 and has long shared a memorandum of agreement with the NPA.

The MOD’s relationship with the NPA and with Dartmoor is perhaps the most enigmatic of all, in the ‘public body’ and the Sandford principle (of the 1995 Act) stakes. Its presence on Dartmoor is of long standing, the Napoleonic Wars saw army camps in the south, and in 1875 the Mayor of Okehampton invited the War Office to indulge an annual artillery camp where it still is, though in buildings now. (The first permanent buildings were erected there in 1892.) So, it is important to remember, Dartmoor was designated a national park in 1951 in the knowledge that soldiers fired shot and shell within it regularly. The shells ceased falling, on or off target, in 1996, but live firing with mortars and small arms is still indulged and so public access continues to be impaired by that. More significantly, for our purposes, a major public inquiry into the military presence was held in 1975 with some useful results. Lady Sharpe, who conducted the Inquiry, concluded that military activity in the Dartmoor National Park was ‘discordant, incongruous and inconsistent’. She reported to the Secretaries of State for Environment and for Defence who remarkably agreed with her phrase; but seeing no early opportunity for the ending of the relationship, which is perhaps why they agreed so readily, she proposed that formal relations between NPA and MOD should be established which would involve regular and joint consideration of the mitigation of the military effect on landscape and public access to it. Despite intractable problems such as elderly unexploded ammunition surfacing from the peat, the net effect in the last decade at least has been the deployment of a military budget for nature conservation purposes on the high moor. Substantial surveys of vegetation and particularly of breeding birds have been carried out at no expense to the NPA; and professional minds have been bent on high-altitude land management as a result which extend into grazing detail, re-wetting of blanket bog and fire control. Everything in the plateau garden with military gardeners is not necessarily rosy but it would take another book to go into that in adequate detail.

THE VOLUNTEERS – PACE THE NATIONAL TRUST

At the voluntary end of the spectrum the picture can get somewhat confused. The Devon Wildlife Trust and the Dartmoor Preservation Association have already been listed as occupying designated nature conservation sites, but the former for instance occupies that land which is actually owned by the National Trust at Dunsford Wood, and White Wood within its Dart Valley Woods reserve is owned by the NPA itself. Some might say conservation energy is being duplicated, but busy and cash-strapped landlords may be relieved to know that a management job is being done on their behalf, if it is. The Dartmoor Preservation Association owns High House Waste upslope from Dendles Wood, but also what might be called ‘preservation monuments’. A strip straddling the valley of the Swincombe, which might have been the site of a dam had the Association and others not defeated the proposal, ranks with another tiny plot on the ridge between Sharpitor and Peek Hill which once was occupied by a wartime radar station whose remnants the Association successfully fought to have removed.

On an altogether bigger scale the Woodland Trust was founded in the early 1980s by Kenneth Watkins, a millionaire woodland devotee, at Harford near the southern end of Dartmoor. It is now a nationally significant organisation with a headquarters in Lincolnshire, but it owns parcels of land known as Pullabrook, Hisley and Houndtor Woods in the Bovey valley adjoining the national nature reserve of that name. It also has scattered woodland blocks at Higher Knowle Wood near Lustleigh, above East Wrey Barton and Hawkmoor in the Sticklepath Fault zone on the line of the Wray valley, at Westcott above the little valley running down to the Teign from Doccombe and at Blackaton Bridge near Gidleigh Mill. Some of these were acquired as conifer plantations with the express aim of converting them back to broad-leaved woods. All are publicly accessible and thus add to the National Park walking portfolio, helping to meet the aspiration in the first National Park Plan that it should be as easy to walk alone in the woods as on the moorland. That Plan also recognised the ‘concealment capacity’ of woodland, not only in terms of coloured anoraks but of parked cars, information displays and public lavatories, so the occupation of it by public-spirited bodies can only be a good thing for the National Park version of landscape management.

The simplest expression of the potentially major alliance – or set of alliances – just rehearsed is, that of the 94,500 ha of the National Park, 41,500 ha are owned by the bodies referred to so far in this chapter. By dint of complicated calculation and adding in the remainder of the total area of commons, whose commoners are NPA partners by virtue of the Act of 1985 and which land’s status is nationally protected in any case, much more than half the Park is in safe hands. The ultimate protection in a property-owning democracy is ownership. The public service companies and authorities listed so far are under a statutory duty to have regard for the National Park purposes in their own management decision making (the Environment Act of 1995), hence their inclusion under that safety cliché.

THE FUTURE OF RURAL CONSERVATION DELIVERY

However, while the land-holding part of the equation, even with the occasional ‘duplication of effort concern’, is a fairly concrete basis for an alliance in the interests of conserving landscape for the public benefit, the regulatory and supportive administration part is more tenuous. The NPA is the sole planning authority and ostensibly controls potential change in the use of any plot of land in the Park from one category to another. This is universally regarded as applying mainly to the erection of buildings (for any purpose) and the creation of their curtilages (so that field to garden is a ‘change of use’). It also involves considerations of appropriate design and thus should be a means for the maintenance of local character in villages and farmsteads, very significant in a national park landscape where the planning authority is effectively acting in the nation’s interest. That is why the importance of the ‘development frameworks’ (as opposed to the National Park Management Plan) which the NPA as planning authority makes to guide the aspirations of any would-be ‘developer’, from large corporation to humble individual, cannot be understated. But in overall park-wide landscape terms it is the administrative influence and the scientific interpretation feeding it, wielded by Natural England, English Heritage, the Environment Agency, at arms-length: DEFRA, and from even further away the European Union, that cannot in this day and age be gainsaid.

A man who lives in a listed building with a national trail passing his front doorstep, inside a national nature reserve, itself within an SSSI and the whole well inside a national park within an ESA can be forgiven for feeling he’s a bit over-supervised. The farmer next door feels he’s under the cosh, and their landlord is the National Trust! OK, it’s not in Dartmoor, but the actual situation still exists and in 1970 I was the ‘man’ (Fig. 259). It is merely another illustration, but this time in the detail, of the early reference in this chapter to the conservation broth and the number of cooks who want a ladle in it. In fact it all

FIG 259. The Old Farm at Waterhouses, Malham Tarn, with the Pennine Way passing the front door; the house is in a nature reserve, itself in an SSSI, in a national park and is owned by the National Trust with the Field Studies Council as tenant – how protected can you get?

began in 1947 when Hobhouse et al. decided that landscape and nature conservation couldn’t be handled by one body and yet there should be national agencies to oversee both. The contrast in the briefs for those agencies stems from the fact that the natural scientists had got their act together by 1949 and knew exactly what they wanted or thought they needed, but the romantics and ramblers had delved very little into what makes landscapes work. In their defence, perhaps no one had. John Dower’s retrospectively valuable recognition of the need for farming to continue did not then represent a wide understanding of the subtlety of optimal grazing and burning management which sustains the mosaic of ground cover outside the moorland wall, and which we now know to be critical, at least in Dartmoor.

In both cases the relationship between national strategic policy-making and action on the ground and how both should be organised, was not thought through and the seeds of a conservation competition were sown. The evolution of both processes has been registered as the development of the contemporary Dartmoor quasi-political scene has unfolded in the last few pages. Both of course also found themselves rubbing shoulders with the historic and archaeological conservation system, because one had to deal with bats and birds in buildings and the other had all the functions of a planning authority about those buildings. All three operators, late in the day, had to take a mutual interest in grazing; and the happy coincidence of the virtues of short-cropped grassland for bird feeding, easier walking and the visibility of elderly and now low-level stone structures brought them together on Dartmoor in 2005 in that attempt to create, with farmers on board, the shared ‘Vision’ for Dartmoor’s vegetation in 2030 to which I have often referred.

That ‘Vision’ process brought together in a strategic judgement, hopefully not too briefly, those three organisations with nearly 50 years’ separate existence. Others joined in, much younger, like the Rural Development Service and the Environment Agency, and the really old, like the Ministry of Defence lately apprised of its wildlife conservation responsibility and spatial potential for it, through its agent joined at the hip – Defence Estates – on a training estate of which Dartmoor bears a fair-sized chunk. The separate existence of the three strictly conservation agencies was probably always inevitable, possibly necessary at the Whitehall level and workable as long as a single minister had oversight of all three. On the ground lie the questions. On Dartmoor things were peaceable enough throughout the first 20-odd years of the life of the National Park from 1951. The committee had little power and no full-time staff, the Nature Conservancy had a remote regional officer based at Furzebrook near Wareham in Dorset, eventually a warden living in the reserve at Yarner Wood, and even later a Chief Warden for South Devon and Dartmoor. But, as we have seen, the 1970s saw a remarkable set of changes in responsibility and powers, a relatively rapid growth in staff and funds and an increased expectation of action by all communities of interest from government downwards. This applied to newly created national park authorities, the youthful Countryside Commission and the newly independent and newly titled Nature Conservancy Council. As the 1980s wore on, more and more farmers were enticed into management by agreement by the NPA, and the Countryside Commission invented a ‘Countryside Stewardship’ experiment targeted at particular landscape features – hedgerows, valley floors and the like. Soon the Ministry of Agriculture joined in with Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESA) in which farmers could volunteer land on which a specific management formula would be pursued – all for cash of course. UK ministers persuaded the European Union, in the early 1990s, that all this was a good thing for the whole continental membership, and thus corporate international funds were deployed by local MAFF ESA project officers and a third force of ecologists joined the fray.

Ecological expertise with agricultural innocence

The potential for a fray must be obvious. Add to the competitive risk the fact that ecology is not an exact science at the best of times. Opinions, theories and the imposition of thinking from one hill – in this case – to another, ignoring simple geographical variations, bedevils the art. The calculation of optimal sheep-grazing numbers per unit area of heather 560 km to the north and in the Pennine rain shadow is unlikely to work on a Dartmoor hill-farm exposed to the southwest wind and all that it carries – enjoying a much longer growing season and higher summer temperatures. But such a grazing formula became a mantra that must be obeyed. A timetable for haymaking is inserted into another formula to foster the biodiversity of the hill-farm home meadows. The necessary time for cutting the grass which will be made into hay varies from year to year on a real farm, and not just with the weather of that season but with the variable demands on the available labour from day to day. Sheep graze the northern hills almost alone but we have already seen that cattle and ponies play a vital role in Dartmoor, complementing the work of sheep to a greater degree than even old MAFF hands had realised. If a farmer is asked to, and paid to, reduce the numbers of cattle on his common, say, it is unlikely that he will keep the balance removed, at all. Where can they go? Poaching the home pastures? Feeding expensively in a shed? Or to market, and release some cash? The last is the likeliest. When the formula is shown to be lacking, there are no cattle to be swiftly redeployed to eat off the now-rank vegetation. Over-grazing symptoms have turned into an actual under-grazed state. But when the ESA ‘contract’ ends (and the maximum length is ten years) the hill-farmer has fewer beasts than made his livestock enterprise viable as a simple stock-producing operation, and in any case he has looked elsewhere in the meantime to seek profit because that is his normal motivation, and nowadays necessity.

In truth, the imposition of the ESA de-motivated the NPA as management agreement maker for financial reasons if no other, and while English Nature (EN, the successor to the NCC) tried to use the grazing formulae in its search for achievement of SSSI ‘favourable condition’ (a DEFRA target for 2010), it hasn’t worked yet. By 2007 the RDS (Rural Development Service, of DEFRA) and EN had become the greater part of Natural England. European writing was on the wall for ESAs, and its successor combination: Single (farm) Payment (with its perverse Moorland Line) and Environmental Stewardship (with its entry-level and higher-level schemes) was proving inadequate for common land and rejected by farmers as unviable for moorland in single ownership, such as newtakes. The Upland Entry Level Scheme may help in 2010, but in effect it merely replaces the Hill Farm Allowance that ends then.

WHAT NOW?

Natural England and its parent DEFRA now not only have to resolve this motivational conundrum if upland moorland is to survive on Dartmoor but almost certainly review the organisational set-up. For NE has also become the parent body of National Park Authorities via its third constituent, the Countryside Agency, successor of the Countryside Commission, itself successor of the National Parks Commission. Ironically we have just achieved a single operator for landscape protection, nature conservation and recreation promotion at national level in England (which Scotland and Wales have had since 1991) but we still have a sad competition and worrying confusion on the ground. Because Natural England includes the old RDS, it administers whatever agri-environmental financial farm support DEFRA can produce. This is new and unlike the situation in Wales and Scotland; it thus remains to be seen whether the whole complex is capable of easy management and the comprehensive success all involved would want it to have.

Logic suggests that Natural England might recognise the virtue of having a set of conservation agents on the ground for areas already statutorily protected. One body, in Dartmoor’s case that charged with the care of the National Park for more than 50 years now, and on which it thus has an inherited grip, could be that agent and deliver all the advice, regulation and financial support available to farmers, who alone have what is needed to maintain the Park’s publicly valued attributes. They would then know with which single authority they were dealing, and that its officers were accessibly based and on the spot. A working relationship between officer and farmer would be developed anew, which the original National Park Plan claimed was necessary for the smooth delivery of public goods by private operators. Of course, in matters of irreconcilable disagreement, there would have to be an appeal system involving the parent body, who still calls the necessary financial tune. The NPA could be required to account for its stewardship annually, be monitored by NE as necessary – but work on the ground would be continuous and constructive. The broth would have one cook, or at least one sous chef

The broth of course, cooks apart, has an age-old recipe and we have examined most of its constituents. It remains to consider them and their freshness, new alternatives, and how the heat of the kitchen may vary not too long hence.