Laura left her room in search of her parents, and found them huddled over a final guest list of people who would be attending the Bat Mitzvah party. They were immersed in trying to decide who they would seat next to whom at the dinner.

‘But Gary, we can’t seat your Uncle Lou next to my cousin Anne,’ Laura’s mother was saying. ‘Don’t you remember that time your uncle insulted my cousin by telling her that he had become sick from the muffins she baked for our last family picnic? He said she tried to poison him. They haven’t spoken since.’

‘Well, there’s no one else to put him with, Lisa,’ her father replied. ‘So they’ll have to pretend they like each other for the night.’

Laura plunked herself down in between her parents, waiting for a lull in the conversation.

‘What is it, Laura?’ her mother finally asked. ‘You’ve looked unhappy for a couple of days now. Are you getting nervous about your Hebrew studies? I know there’s a lot to learn, but you can’t let it get to you.’

Laura shook her head. ‘No, Mom, I keep telling you – that part’s fine. It’s just this twinning project and the book that Mrs Mandelcorn gave me.’ By now, Laura had told her mother about receiving the diary, but little else.

Laura’s parents waited expectantly. That was the great thing about them, Laura realised. Her parents never pushed her to talk when she was troubled. They let her take the lead, waiting until she was ready and then putting aside everything, just like now, to be there and listen.

Laura began to talk about Sara, her parents, grandmother and siblings. ‘I don’t know much about the Warsaw Ghetto. I’m just starting to find out some stuff about it.’ Laura’s research had begun. She had already gone online, trying to find out some facts about the ghettos in Europe during the war – when they were formed, how, and what had happened there. Suddenly, the additional work seemed so important. When had Laura moved from feeling this was a burden, to feeling it was necessary?

‘I knew that the ghettos were often built by the prisoners themselves,’ her father said. ‘There was a speaker at our synagogue last month; your mom and I went to hear him. His name is Henry Grunwald. He is a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto and talked about how he and the other Jewish prisoners had to build the walls.’ Laura’s father went on to talk about how the ghettos were constructed next to railway stations. ‘Mr Grunwald said that at first, the ghettos were there just to keep Jews separate from their neighbours. But once the Nazis started taking Jews to the concentration camps, it was easy to collect them from the ghettos and load them onto the trains. I never knew that before.’

Laura nodded. She didn’t yet know what was going to happen to Sara, but already she had a sense of foreboding about the outcome of her story. Things could only get worse.

‘Mr Grunwald’s talk was so moving. Gary, do you remember when he talked about the revolt in the ghetto?’ her mother asked, before turning to Laura. ‘They called it the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.’

Laura interrupted. ‘I know. I’ve been reading about that too.’ It was late in the war and most of the Jews from the ghetto had already been deported to the death camps. But there was a secret underground organisation of young Jewish fighters who banded together to fight back with whatever they had – a few guns, handmade bombs and grenades.

‘They were so badly outnumbered,’ her father went on. ‘One small group of fighters against an entire Nazi army. The Jews were bound to lose. But miraculously, the battle actually lasted for several weeks. The Nazis never expected the Jews in the ghetto to fight against them.’

Laura’s mother continued with the story. ‘You can imagine how humiliating it was when a handful of inadequately equipped, poorly trained young Jewish men and women were able to slow down the plans that the Nazis had in place for deportation. The Nazis finally set fire to what was left of the ghetto. The Jewish fighters were unbelievably courageous, right up until the end.’

Silence hung in the air as Laura tried to digest what her parents were telling her. She already thought Sara was courageous, and she had barely begun to find out about her life.

‘There are so many things I just don’t understand about what happened during the war,’ Laura said finally. ‘I thought I knew this stuff from the project I did last year, but I really don’t.’

‘It’s hard for any one of us to understand how these things happened, Laura,’ her father replied. ‘Jews became scapegoats for Germany and the troubles it was experiencing after World War I. But that’s not what you’re looking for, is it?’

Laura shook her head. She didn’t want historical information about the events leading up to World War II. She wanted more than that. She wanted to know what Sara seemed to be asking – why the world had stood by and allowed these events to unfold in the first place.

‘This project is becoming important to you, isn’t it, honey?’ her mother asked gently.

Laura nodded. ‘Nix doesn’t understand. She thinks I’m an idiot for not being more excited about my dress right now.’

Her mother nodded. ‘You and Nix are good friends. You’ll find a way to work that out.’

Laura nodded again. She kissed her parents goodnight and retreated to her bedroom. There was an email from Nix waiting for her on her computer. I don’t get it, the email said. Why are you more interested in some girl who lived a million years ago?

Laura stared at the computer screen. She didn’t feel like answering Nix. As she got ready for bed, Laura’s head was clouded with questions and uncertainty. Perhaps she would never understand why things had happened as they did during the war. The one thing she did know was that she had finally made a commitment to the twinning project. And if her best friend couldn’t understand how she felt about Sara and her life, well, that was too bad.

Laura turned off her computer without answering Nix’s email. When her books were put together for the next day, Laura finally climbed into bed. Only then did she reach for the leather-bound diary, and opening it, she began to read.

David went out again last night, and this time he didn’t return until the sun was coming up. I don’t know where he goes and he doesn’t say much. I’ve tried to ask him. But he just shrugs his shoulders and mumbles, ‘Just out.’

I know there’s more to it than that. I know there are groups of people organising to fight back against the Nazis. David doesn’t know it, but I overheard him once. He was in the courtyard of our building with his friends, Luba and Josef. David didn’t see me standing behind the door. And that’s when I heard them talking.

‘We are strong. There are more and more of us each day,’ David was saying. ‘Soon we’ll have enough to be able to do something.’

I didn’t know who ‘we’ were, or what kind of action he was talking about. There was no Jewish army here in the ghetto.

‘We’ve already managed to sneak some Jews out,’ David continued. ‘We’ve gathered arms and ammunition. It won’t be long before we put these things to good use.’

David lowered his voice and looked around. I shrank back into the shadow of the doorway and strained to hear what he was saying.

‘There will be another transport soon,’ whispered Josef. ‘We won’t sit by and watch our brothers and sisters be taken away. We’ll fight.’

‘There are not enough of us.’ Luba was talking now. ‘And what will we fight with? Twenty rifles won’t stand up to one of their tanks.’

‘I’d rather die fighting here in the ghetto than be taken away,’ said David.

With that, he turned and started to walk back through the courtyard. I must have made a noise, stumbled on a loose brick because David caught me hiding behind the door. At first he was angry at me for eavesdropping on his conversation, but I didn’t care. That’s when I told him I wanted to help him with whatever he and his friends were planning. David wouldn’t hear of it.

‘You’re a kid,’ he said. ‘Way too young. And you have no idea of the dangers out there.’

‘But if you can do something, then why can’t I?’ I demanded. ‘Besides, I’m twelve. If I’m old enough to be here, then I’m old enough to help. I can do whatever you do.’ Where did I get the courage to confront David like that? It’s something Deena would have done, but not me!

Even David looked surprised at my outburst and stared at me a long time before answering.‘What do you think you’re going to do? Smuggle guns into the ghetto? Just last week, my friend, Jakob, was caught with a pistol on Chlodna Street. He probably didn’t even see the military car that pulled up behind him. He was dead in an instant.’ David stepped closer to me. ‘I won’t let you do something so dangerous.’

That’s when I ran back upstairs. I didn’t want to hear anymore. I didn’t want to hear about people being shot. I didn’t want to hear that there would be a transport out of the ghetto. And I didn’t want to hear that my brother and others were going to fight with guns against Nazi tanks.

November 26, 1941

I know about transports and deportation. I know what the words mean. ‘Deportation: to be banished or exiled from your home and sent to an unknown destination.’ I once looked it up in the dictionary. And I, like everyone in the ghetto, have heard the rumours about where Jews are being sent. You’d have to live with your head buried in the sand not to be aware of the news that sweeps through here. Deena and I sometimes talk about it.

‘Those prisons in the east,’ I said one day as we sat on the stairs in front of my apartment. ‘Do you think they’re as bad as everyone says they are?’ Deena and I were tossing an old ball back and forth. David had pulled the ball out from a pile of garbage one day, and he had given it to me – one of those rare gestures that told me he still sort of cared about me, even if he didn’t say so. The ball was almost in shreds; the top layer was hanging by a thread. But David covered it in cloth and wrapped it in some chicken wire that he also found. So it was fine, and it gave me and Deena something to do besides just sit and watch the miserable people walk by.

Jewish resistance fighters could be stopped and arrested by the Nazis.

Deena tossed the ball from one hand to the other as she thought about my question. ‘Rumours are a dangerous thing,’ she finally said. ‘We can’t know what’s true and what’s exaggerated.’

Sometimes, I think that Deena knows more than she lets on, just like my parents, and just like David. Deena is my age, but sometimes she thinks she needs to protect me from things, as if I can’t handle the truth as well as she can. Deena knows me well, and sometimes I’m grateful that she doesn’t talk about the things that she knows – like when she tells me she’s in a hurry to draw everything she sees in the ghetto. But this time, I pushed her to say more.

‘They say that Jews who are being deported are being killed in those prisons,’ Deena said slowly. ‘They say we’re better off here in the ghetto, and that to be transported away is a death sentence.’

I had never imagined that this horrible place could be a better alternative to anything. But Deena’s words made me shiver uncontrollably. And it reminded me of something. ‘Do you remember when Mordke’s parents were arrested?’ I asked. Mordke was a boy my age who lived in a crowded flat with his parents and two other families. I used to stand with him by the gate, waiting for his parents and my Tateh to return to the ghetto after working in the factories on the outside. One day, Mordke’s father tried to sneak some food past the guards at the gate. He had somehow managed to find or steal a head of cabbage that he tried to hide inside his coat. But the guards were searching everyone that day, and when they found the cabbage they beat Mordke’s father and threw him on a truck. I thought that Mordke was going to charge the guards, and I had to hold him back so he wouldn’t be beaten along with his father. Mordke struggled in my arms but I held him tightly and told him to be quiet. When Mordke’s mother tried to help her husband she was also thrown on the truck. Just like that! Mordke’s parents were arrested and taken away, and Mordke was left to fend for himself in the ghetto. It was so sad to see him all alone after that, begging on the streets just like the old sick people. Mama often brought him into our home to share what little food we had.

‘Here’s the thing,’ I said as I grabbed the ball from Deena’s hands and turned her to face me. ‘We’ve all felt so sorry and sad for Mordke. He’s here all alone in the ghetto. But at least he’s still here. Maybe the people we should feel sad about are his parents.’

Deena just stared at me. She had no response, and in that moment, I realised the rumours must be true.

December 19, 1941

Freezing cold! My fingers and toes are numb. I am sitting indoors, under a blanket. No heat.

January 12, 1942

Tateh took me to visit the orphanage today. He knows the man who runs it. His name is Janusz Korczak. ‘He’s a great man,’ Tateh says. ‘A generous human being.’ Tateh used to teach at the orphanage; that’s how he came to know Mr Korczak. Actually, he is really Dr Korczak, but he gave up his medical practice when he decided to devote his life to taking care of orphans. He even once ran a home for Catholic orphans and dreamt of creating a place where Catholic and Jewish children could live together. That’s what Tateh told me. Isn’t that a lovely idea? Children of different religions living together like brothers and sisters. It’s the way things ought to be. Of course, it never happened. In fact, eventually Dr Korczak wasn’t allowed to be the director of the Catholic orphanage because he was Jewish. And when the ghetto was created he decided to stay here with the Jewish children he was taking care of.

I hadn’t wanted to go with Tateh to the orphanage. I was feeling particularly hungry that morning. It isn’t fair that there is so little to eat in the ghetto. There was a time long before the war when our icebox was so full that when you opened the door, it felt as if the food was going to leap out. These days, the cupboards echo with emptiness along with my stomach. Here is what we get to eat in the ghetto. There is one midday meal from the central kitchen, but I wouldn’t call it a meal at all; it’s really just a bowl of watery soup with a few vegetables floating on top. The ration card that Tateh has gets us 800 grams of bread a month and 250 grams of sugar. With that we get a few potatoes and sometimes some cabbage or beets; if we’re lucky, a few grams of jam. And that’s it! Mama barters for other things like a soup bone, or a few grams of cheese. But there is less and less to barter with. Soon, she will have to start pulling up wooden slats from the apartment floor!

I long for just one of Mama’s meals that she used to make in our old home – one plate of roast brisket with sweet potatoes and carrots. In those days, I used to eat meals with hardly a thought about what I was putting in my mouth. These days, eating the little food we have is something that requires concentration. Each bite is deliberate; each mouthful memorable.

‘Stop feeling so sorry for yourself, Saraleh,’ said Tateh. That’s when he said I had to go with him to the orphanage. ‘Dr Korczak is a friend of mine,’ he said. ‘I want to talk to him about doing some teaching again at the orphanage. It will be good for my soul.’

I didn’t know what that had to do with me or why I had to go along.

‘Perhaps this will put your life in some perspective,’ Tateh said, though I didn’t quite know what that meant.

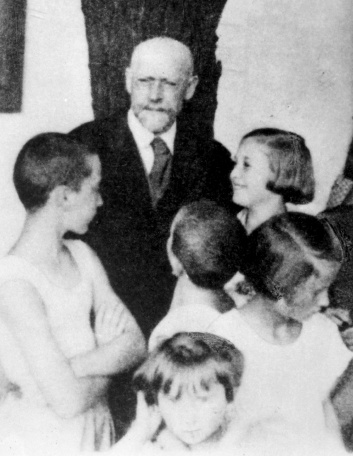

Tateh and Dr Korczak were happy to see one another and embraced like long-lost friends. I stared at Dr Korczak. He is tall and thin and has a head as round and bald as a full moon. The children stood in quiet rows behind the doctor – about twenty of them. The oldest was about twelve, the youngest no more than four or five. Their eyes were curious.

‘Stay here with the children,’ Tateh told me. ‘I’m going to talk with Janusz. I won’t be long.’

As soon as Tateh left with Dr Korczak, I was surrounded by a group of boys and girls. Most of them could not have been more than Hinda’s age, and I felt sadder than when I had left my cat behind before coming to the ghetto. These children had no parents, no grandparents to look after them and to love them. Not only were they here in this horrible ghetto, but they were completely alone. And yet, they did not seem unhappy at all. In fact, Bubbeh looked sadder than these young children, and she had all of us!

People had to line up at the central kitchen for the midday rations.

The children tugged on my hand, wanting me to come with them and play. I followed them into a larger room where they surrounded me with looks of such expectation that I suddenly had an idea.

‘All right, everyone,’ I said. ‘Sit down and I’ll tell you a story.’

The children plunked themselves down at my feet and I began to tell them the legend of the trumpeter of Krakow.

Janusz Korczak cared for the children in the orphanage.

There was a watchman who stood guard in the tallest tower in the city of Krakow – the Mariacki Church of Saint Mary. This watchman would blow his trumpet if he believed that the city was in danger.

One night, the watchman saw a group of invaders approaching. He blew his trumpet to alert the townspeople. The invaders shot arrows at him in the tower, but he continued to blow the trumpet until he was hit in the throat by an arrow.

Eventually, the invaders were forced back, the city was saved, but the watchman died from his wounds.

Since that time, a trumpeter always plays a little hymn in Krakow, repeating it every hour. It ends on a high note to honour the watchman who died protecting his city.

As I told the story, one little boy’s face caught my attention. He had dark hair, dark eyes and freckles across his nose just like me. His eyes grew so round as I told my story that I thought they would pop out of his face. I was just finishing up when Tateh and Dr Korczak entered the room.

‘That one will certainly grow up to be a fine teacher, like you,’ said Dr Korczak, pointing at me while Tateh smiled approvingly.

Before leaving, I said goodbye to the children, pausing to speak to the little boy with the freckles.

‘Did you like my story?’ I asked. He nodded. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Jankel,’ he said. ‘Will you come back? Will you come and tell us another story?’

‘I’ll try,’ I said, reaching down to give him a hug before following Tateh out the door.

‘It was a good thing you did, Saraleh,’ said Tateh. ‘These poor children have nothing. If it weren’t for Janusz, who knows what would happen to them? He finds them food and clothing and beds to sleep in. There are even activities and plays that Janusz organises for the children. Imagine, here in this squalor, these children are able to play.’

I was quiet on the walk back to the apartment, thinking about what Tateh had said. That morning I had felt like the unfortunate one. I had so little to eat, and no new clothes, and a cramped room that I shared with my grandmother. But compared with these children, I felt as if I had all the riches in the world. I had my parents, Bubbeh, Hinda and even David, whether or not he talked to me. It was amazing how one person’s misfortunes could suddenly make your own life seem so much better. I vowed right then and there to return to the orphanage whenever I could.

January 16, 1942

Yesterday, David left the house without his armband. That’s against the law and you can be arrested or even shot if you are caught without one on. Everyone must wear the white armband with the blue Star of David whenever we are outside. I hate my armband. It’s like a vice wrapped around my arm, squeezing tighter and tighter, reminding me that I am different. We have to make our own armbands, or buy them from the boy on the street who walks around carrying dozens of them on a stand. Mama refuses to pay for the armbands. She says it’s just like the construction of the ghetto. ‘The men built the prison and now the women have to buy the prison uniforms. Ridiculous!’ she says. So instead, Mama, Bubbeh and I sew them by hand. It gives Bubbeh something to do, something to keep her mind off her sadness.

Some girls sewed clothing in the orphanage.

Boys and girls had lessons, worked in the garden, and put on plays and concerts.

I saw David’s armband lying on his cot. So I ran after him to tell him he wasn’t wearing it. I thought maybe he had just forgotten. Well, I should have known better. When I caught up with David around the corner from our apartment, he turned around and hissed at me to leave him alone and get back inside.

I didn’t want to tell Mama and Tateh, didn’t want to worry them. So I sat on David’s cot and rocked back and forth. Mama thought I might be sick and she kept pressing her lips to my forehead to see if I had a fever. The truth is I was sick with fear for David’s safety.

He came back late that night, and you won’t believe this. When David opened his coat, food fell out from the inside! There were two bunches of carrots, a head of cabbage and some onions. He even had a bag with sugar and one with flour that he pulled from his pockets. It was as if a treasure had fallen from the sky; that’s how incredible this was! Mama threw herself at David, hugging him and squealing with delight. But in the next minute, I thought she was going to throttle him. We didn’t know what he had done to get the food, but we knew it must have been ridiculously dangerous.

Later that night, when everyone was sleeping, I went to David’s cot and I asked him point-blank how he had gotten everything. At first, he didn’t want to tell me. But I just stood there and waited. I think I have a right to know these things. And finally, David began to talk. He told me that there is a way to get out of the ghetto – holes in the walls that some of the Jews have created. David crawled through one of these holes and went scavenging for food.

Jews made their armbands or bought them from vendors on the street.

Everyone in the ghetto had to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David.

‘I went back to the old market close to our house,’ said David. ‘Mr Novakowski was still there, selling his goods as if nothing had changed in the world. When he saw me walk into his store, I thought he’d have a heart attack.’ David would have been arrested on the spot if he, a Jew, was seen on the streets of Warsaw. But we both knew that Mr Novakowski might also be punished if he was seen talking to a Jew. ‘That was my one advantage,’ continued David. ‘I thought Mr Novakowski would do anything to get me out of there as quickly as possible. He shoved all this stuff into my hands and I disappeared as quickly as I could.’

David said that the hardest part was walking back to the ghetto. ‘It was like a taste of freedom,’ he said. ‘Better than all the vegetables I carried in my pockets.’

Listening to David talk about being on the outside of the ghetto walls was more than I could ever imagine. I was light-headed just thinking about it. ‘Take me with you!’ I blurted the words before I had a chance to think. ‘The next time you go out – take me with you.’ I didn’t even think about the danger. ‘Please, David,’ I pleaded. ‘I have to do something. I’m small,’ I added. ‘I could crawl in places you couldn’t get to.’

David stopped. For a moment I thought he might snap at me again, tell me to leave him alone, tell me I’m too young to get involved. But this time he didn’t. And after a moment, he said, ‘I’ll think about it.’

The next day, we feasted on a stew that Mama made. She even put in a meat bone that she had been saving for a special occasion. My stomach felt fuller than it had in weeks. But the best part was that David actually said I might be able to help him. Wouldn’t that be the greatest irony – if the ghetto brought David and me closer together?