‘I’m so glad you called me, Laura,’ said Mrs Mandelcorn. ‘At my age, I don’t get many visitors. More cake?’

Laura was sitting in Mrs Mandelcorn’s living room. Two days had passed since the incident in the cemetery. The police had not yet been able to solve the crime and were still appealing to the public to come forward with information.

‘The police think it happened in broad daylight,’ Laura’s father had said the next morning. ‘Surely someone must have seen something – maybe someone from your school, kiddo?’

Laura had swallowed guiltily and looked away. She didn’t know how to respond to her father’s question, and it was unnerving to sit there under his inquisitive gaze. She wanted to shout out loud, ‘Yes! Someone saw it and that someone happens to be my best friend!’ – or rather ‘was my best friend’. Laura and Nix had said nothing to each other since their late-night telephone conversation. It was the longest they had gone without talking all year. Even when Nix and her family had been away in the Caribbean at Christmas, the two girls had still emailed on a daily basis. Now the lines of communication had gone silent and cold.

At school, Laura avoided her friend, taking the long way around staircases and hallways so she wouldn’t accidentally bump into Nix between classes. She ate her lunch with Adam and tried to steer the conversation away from Nix and the events in the cemetery.

‘I say she’s guilty,’ Adam had declared the next day when he plunked himself down next to Laura in the cafeteria.

‘Be quiet!’ Laura responded harshly, but backed down as soon as she saw Adam’s hurt expression. ‘Sorry. I’m just swamped; homework, my Bat Mitzvah, Sara’s diary – and now this cemetery thing. I’d rather not talk about Nix, okay?’

Adam had shrugged and turned back to his lunch. But while she might not have been talking about recent events with anyone, Laura certainly couldn’t stop thinking about them – day and night. And it had gotten even worse after reading Sara’s last entry – the roundup of her friend, Deena, and others for deportation from the ghetto. Laura had had two more dreams the night before. One was about being a freedom fighter; Laura was crawling on her belly, through a darkened tunnel, a gun in her hand, when she woke up in a twisted mess of sheets and blankets. When she finally fell back asleep, she dreamt that she, Adam and Nix were on a train heading for some terrible unknown destination. That dream was even more terrifying than the first.

The next day, Laura decided to pay Mrs Mandelcorn a visit. Perhaps she could talk to this woman in a way that she couldn’t yet bring herself to talk to her parents or Adam.

‘So, what can I do for you, my dear? You sounded very unhappy on the telephone.’ Once again, Mrs Mandelcorn had kept Laura waiting in the living room when she first arrived at the apartment. But now, the elderly lady took a deep breath and settled back on the sofa.

Where to begin? There was so much that Laura wanted to ask about – the diary, Sara’s life, the vandalism in the cemetery, Nix. Taking a deep breath, Laura finally plunged forward. ‘I’m reading about Deena’s deportation from the ghetto. It must have been horrible for Sara to see her friend go like that.’

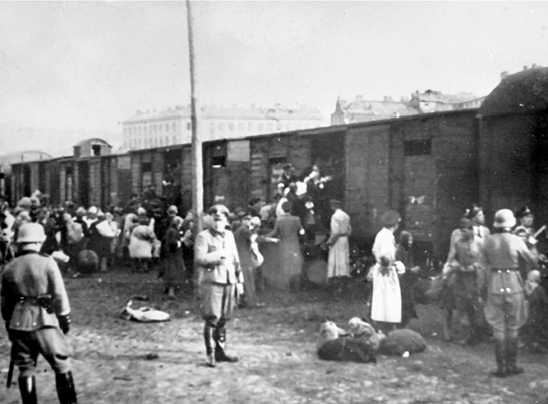

Once more, a cloud passed across Mrs Mandelcorn’s eyes. She sat heavily, breathing deeply as if she were moving into a trance, transported to another time and place. And then, slowly she began to talk, filling in some pieces of history for Laura. ‘Those roundups took place in the summer of 1942. Each day, thousands of Jewish men, women and children were marched to the train station at Umschlagplatz, loaded onto boxcars and sent to Treblinka. Have you heard of this concentration camp, Laura?’

‘I’ve heard of it, but I don’t know very much.’

‘It was one of the worst of the death camps, about one hundred kilometres north-west of Warsaw. There were two camps there; Treblinka I, a forced labour camp, and Treblinka II, the location of the gas chambers.’

Laura knew about the gas chambers. She shuddered to think how millions of Jews had been killed.

‘The path from Camp I to Camp II was called Himmelstrasse,’ Mrs Mandelcorn continued.

‘What does that mean?’ asked Laura.

Mrs Mandelcorn laughed bitterly. ‘The Road to Heaven,’ she said. ‘That’s what the Nazis called it. Of course, it was really a path that led to death.’ Laura was transfixed by what she was hearing. Even Mrs Mandelcorn’s accent had become irrelevant, moving into the background where it was hardly noticeable.

‘Can you imagine this, Laura? The Nazis decorated the entrance to Treblinka to look like a train station. There was a train schedule posted on the wall listing arrivals and departures. There were posters everywhere of places to visit. There was even a large clock that was set for the next arrival.’

‘Why would they do that?’ Laura interjected.

Mrs Mandelcorn shrugged. ‘All part of the Nazi deception. The prisoners thought they were meeting other family members there. They didn’t suspect that they were about to be killed.’

At that, Mrs Mandelcorn lowered her head, shaking it silently from side to side. When she finally looked up, there were tears glistening in her eyes. ‘Sometimes memories are a dangerous thing,’ she said. ‘Too many ghosts in the past.’

‘How do you know all of this?’ Laura asked. ‘Were you there?’

Once again Mrs Mandelcorn looked down. Laura sensed that she couldn’t press the elderly woman any further, but her own head was pounding. There were so many questions; so many things she wanted to know. And one question echoed more than any other – what had happened to Deena and Sara? Somehow Laura couldn’t bring herself to ask. She still had to finish the journal – she had one section left to go. But she was dreading the ending now more than ever.

‘Most were killed in those transports,’ continued Mrs Mandelcorn, more softly, as if she were reading Laura’s mind. ‘So few survived.’ Then she shook her head. ‘Come, have another piece of cake. You are a little bird. Eat. Eat.’

Laura sighed. Clearly Mrs Mandelcorn didn’t want to talk about the past anymore and neither did Laura. Instead, she steered the conversation to the events in the cemetery. ‘Doesn’t it upset you that these things are happening now?’

Mrs Mandelcorn nodded slowly. ‘This is a terrible thing that has happened. But you must remember, Laura, that we are living in a democratic country where such acts of anti-Semitism are not tolerated. This is not Nazi Germany or Poland where singling out Jews was acceptable, even the law. I trust the police here to find the people who did this and bring them to justice.’

Well, they could find them a lot easier if they had help, thought Laura bitterly.

‘But there’s more, isn’t there?’ asked Mrs Mandelcorn, eyeing Laura carefully. ‘Something else that troubles you?’

Laura squirmed uneasily. Was she about to betray Nix by telling this complete stranger what she knew of the vandalism? And was it betrayal if you were telling the truth? It was wrong of Nix to turn her back on the crime; of that, Laura was certain. And it was that truth that was pushing Laura to do something, to tell someone. There was something about Mrs Mandelcorn that tugged at Laura. She trusted this woman – she couldn’t explain why since she barely knew her. And yet, an important connection was there.

‘I have a friend,’ began Laura cautiously. ‘She thinks she might possibly know something about the vandalism. But she’s too afraid to say anything.’

‘Ah, I see,’ said Mrs Mandelcorn, nodding slowly.

Laura went on to explain that the culprits were known bullies in her school. ‘But my friend is totally wrong by not saying anything, isn’t she? I mean, she’s being a complete coward. She’s only thinking about herself and not the victims here.’ Now that Laura was talking she couldn’t stop her feelings from flowing. ‘My teacher at school once said that the Holocaust didn’t happen in the gas chambers. By then it was too late. It happened with acts of discrimination just like this – one after another with no one doing anything about it.’

‘This is true,’ said Mrs Mandelcorn. ‘There were not enough people who were willing to be witnesses in the face of Nazi threats to their own safety. I understand what fear can do.’

‘What would you do if you were me?’ Laura asked quietly. ‘Would you also keep quiet or would you go to the police?’ Laura had already imagined the scene in her mind, the chain of events that would unfold. She would tell on Nix, who would be forced to confess to the police, who would arrest the teenagers who had committed the crime. In the end, justice would be served. But would it be worth it? She would jeopardise her friendship with Nix and possibly her own safety. It was hard to know what to do.

Men, women and children boarded trains destined for Treblinka.

The Nazis decorated the entrance to Treblinka to look like a normal train station.

Mrs Mandelcorn reached over and placed her hand on Laura’s arm. ‘I think this is a question you will have to answer for yourself.’

Laura looked away. ‘It’s the diary – Sara’s journal. That’s what’s making me think so much.’ Sara’s stories were compelling Laura to do something. After all, she was supposed to honour Sara’s life through her own Bat Mitzvah. If she didn’t do something with the information about the cemetery, then what did Sara’s stories and her life really mean? There was only one answer here and Laura knew it.

Laura turned to face Mrs Mandelcorn. ‘Did you ever have a Bat Mitzvah?’

Mrs Mandelcorn shook her head and a soft smile crossed her lips. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘These things were not possible for girls like me.’

‘Would you like to come to mine? I mean, only if you really want to. But you’ve been so helpful and everything. You can bring someone if you want – your sister maybe?’

This time, a large smile lit up Mrs Mandelcorn’s face. ‘Thank you, my dear. It would be an honour.’