In communities around the world, Jewish boys and girls celebrate their Bar Mitzvah (age thirteen for boys) and Bat Mitzvah (age twelve for girls). It is a time when Jewish children come of age and a time when they are required to follow the rules and traditions of the Jewish religion. Boys and girls may study for many months leading up to their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs. On the day of their ceremony, they go to the synagogue and are asked to recite prayers and blessings from the Torah – the scroll of Jewish teachings. This is an important event in the lives of Jewish children, and the ceremony is often followed by a celebration of some kind, with food, gifts and festivities.

In recent years, in an attempt to make the Bar and Bat Mitzvah an even more meaningful experience, synagogues have encouraged young people to ‘share’ their ceremony with a Jewish child who lived during World War II and the Holocaust. In most cases, these children did not survive the war. Of the six million Jewish people who died or were killed at that time, we know that at least one and a half million were children under the age of sixteen. In some cases, young people will ‘share’ their coming of age with a living survivor of the Holocaust, one whose childhood was interrupted by the war and therefore never had the opportunity to have a Bar or Bat Mitzvah.

When a young person today shares their special ceremony with a child of the Holocaust, this is an opportunity for many of these lost children to be remembered and honoured in a small way. This program has become known as the Twinning Program.

The characters in The Diary of Laura’s Twin are fictitious. But there are many real historical elements to this story. The Warsaw Ghetto was a real place during World War II, the largest Jewish ghetto that was established by the Nazis. It was built by Jews in October 1940, and was completely closed off by November of that year. By this time, there were almost a half a million Jewish people there, imprisoned behind high walls in an area that measured only 3.3 square kilometres.

Life inside the ghetto was harsh; there was terrible overcrowding, little food, and disease. Thousands of people died from these conditions. Some Jews were able to find work. But under the watchful eye of their Nazi bosses, they found this work to be backbreaking and tedious.

Beginning in July 1942, the Nazis began to deport the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto to the Treblinka concentration camp. Jews were rounded up and marched to Umschlagplatz, the central square. From there, they were loaded onto trains and sent to the death camp. More than 300 000 Jews were sent from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka. Very few of those who were deported managed to survive.

Jewish resistance fighters lie in the Warsaw Ghetto rubble as the their belongings are searched.

Inside the ghetto, a number of Jewish men and women banded together in an attempt to fight back. They became known in Polish as the Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB) or the Jewish Fighting Organisation. Their commander was Mordechai Anielewicz. At the age of twenty-three, he worked with the ZOB inside the ghetto and coordinated with the Polish Underground to secure weapons and train the young Jewish fighters to resist further deportations.

The destroyed Warsaw Ghetto after the uprising.

The rebellion of the Jewish fighters became known as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, and it began on April 19 1943. The Nazis expected that they would crush the Jewish revolt within days. They greatly outnumbered the resistance with their large army and superior weapons. But in fact, the uprising lasted for one whole month. The Jewish fighters would not surrender. Using crudely made grenades, a few rifles and other handmade explosives, they managed to drive the Nazis back. Finally, the Nazis were compelled to burn down the ghetto in an attempt to rid it of any remaining resistance soldiers. Many months after the formal end of the uprising, there were still reports of Jewish fighters in hidden bunkers who continued to battle against Nazi soldiers.

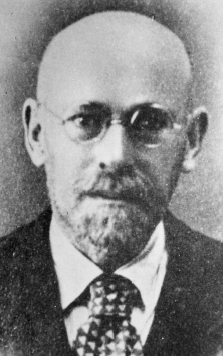

Janusz Korczak was a Polish doctor and educator who was imprisoned in the ghetto and was the director of the orphanage there. He had been the director of the Jewish Orphanage in Poland before the war. It was then that he dreamt of opening an orphanage where Jewish and Catholic children would live together. This of course never happened. While inside the ghetto, there were several opportunities for Dr Korczak to be smuggled out. But he refused to leave his children. On August 6 1942, the children of the orphanage, along with Dr Korczak, were deported to the Treblinka concentration camp. Witnesses in the ghetto reported that the doctor and the children marched to the train station bravely and with quiet dignity.

Janusz Korczak

Throughout his life, Dr Korczak believed that there needed to be a declaration of children’s rights in the world. Based on his teachings and his writings, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989. These rights include the right a child has to receive love, the right to protection, the right to respect, the right to happiness, and many others. To date, more than 190 countries around the world have signed the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child. Thanks to Dr Korczak, children’s rights are being recognised and respected around the world.