Over time, the Romans expanded the borders of their African province. Colonization was encouraged, and the region enjoyed four centuries of prosperity.

For more than a century from its acquisition in 146 BCE, the small Roman province of Africa (roughly corresponding to modern Tunisia) was governed from Utica by a minor Roman official, but changes were made by the emperor Augustus, reflecting the growing importance of the area. The governor was thenceforward a proconsul residing at Carthage, after it was refounded by Augustus as a Roman colony, and he was responsible for the whole territory from the Ampsaga River in the west to the border of Cyrenaica. The proconsul also commanded the army of Africa and was one of the few provincial governors in command of an army and yet formally responsible to the Senate rather than to the emperor. This anomaly was removed in 39 CE when Caligula entrusted the army to a legatus Augusti of praetorian rank. Although the province was not formally divided until 196, the army commander was de facto in charge of the area later known as the province of Numidia and also of the military area in southern Tunisia and along the Libyan Desert. The proconsulship was normally held for only one year; like the proconsulship of Asia, it was reserved for former consuls and ranked high in the administrative hierarchy. In the 1st century CE it was held by several men who subsequently became emperor—e.g., Galba and Vespasian. The commanders of the army normally held the post for two or three years, and in the 1st and 2nd centuries it was an important stage in the career of a number of successful generals. The two Mauretanian provinces were governed by men of equestrian rank who also commanded the substantial numbers of auxiliary troops in their areas. In times of emergency the two provinces were often united under a single authority.

Tribes on the fringe of the desert and beyond constituted more of a nuisance than a threat as the area of urban and semiurban settlement gradually approached the limit of cultivable land. A number of minor conflicts with nomadic tribes are recorded in the 1st century, the most serious of which was the revolt of Tacfarinas in southern Tunisia, suppressed in 23 CE. As the area of settlement extended westward as well as to the south, so the headquarters of the legion moved also: from Ammaedara (Haïdra, Tun.) to Theveste under Vespasian, thence to Lambaesis (Tazoult-Lambese, Alg.) under Trajan. Tribal lands were reduced and delimited, which compelled the adoption of sedentary life, and the tribes were placed under the supervision of Roman “prefects.” A southern frontier was finally achieved under Trajan with the encirclement of the Aurès and Nemencha mountains and the creation of a line of forts from Vescera (Biskra, Alg.) to Ad Majores (Besseriani, Tun.). The mountains were penetrated during the next generation but were never developed or Romanized. During the 2nd century stretches of continuous wall and ditch—the fossatum Africae—in some areas provided further control over movement and also marked the division between the settled and nomadic ways of life. To the southwest of the Aurès a fortified zone completed the frontier defensive system, or limes, which extended for a while as far as Castellum Dimmidi (Messad), the most southerly fort in Roman Algeria yet identified. South of Leptis Magna in Libya, forts on the trans-Saharan route ultimately reached as far as Cydamus (Ghadāmis).

In the Mauretanias the problem was more difficult because of the rugged nature of the country and the distances involved. The encirclement of mountainous areas, a policy followed in the Aurès, was again pursued in the Kabylia ranges and the Ouarsenis (in what is now northern Algeria). The area round Sitifis (Sétif) was successfully settled and developed in the 2nd century, but farther west the impact of Rome was for long limited to coastal towns and the main military roads. The most important of these roads ran from Zarai (Zraïa) to Auzia (Sour el-Ghozlane) and then to the valley of the Chelif River. Subsequently the frontier ran south of the Ouarsenis as far as Pomaria (Tlemcen). West of this area it is doubtful whether a permanent road connected the two Mauretanias, sea communication being the rule. In Tingitana, Roman control extended as far as a line roughly from Meknès to Rabat, Mor., including Volubilis. Evidence attests to periodic discussions between Roman governors and local chieftains outside Roman control, suggesting peaceful relations. However, the tribes of the Rif Mountains must have lived in virtual independence, and they were probably responsible for a number of wars recorded in Mauretania under Domitian, Trajan, Antonius Pius (which lasted six years), and others in the 3rd century. They did little or no damage to the urbanized areas and never necessitated a permanent increase in the African garrison. The defense of the North African provinces was far less a problem than that of those on the northern periphery of the empire. For Numidia and the military district in the south of Tunisia and Libya, about 13,000 men sufficed; the Mauretanias had auxiliary units only, totaling some 15,000. This may be contrasted with the position in Britain, where three legions and auxiliaries (all told, some 50,000 men) were required. From the mid-2nd century CE the African garrison was largely recruited locally.

The most notable feature of the Roman period in North Africa was the development of a flourishing urban civilization in Tunisia, northern Algeria, and some parts of Morocco. This was possible because nomadic and pastoral movements were controlled, which opened large areas of thinly settled but potentially rich land to consistent exploitation. Also there was the incipient urbanization of some parts, owing to the Carthaginians and the ambitions of Libyan rulers such as Masinissa. In addition, Italian immigrants were settling in Africa; though relatively few in comparison with the population as a whole, they provided the impetus to expand. Julius Caesar settled many veterans in colonies, mostly coastal towns, and, equally important, established a military adventurer named Publius Sittius along with many Italians at Cirta, beginning the Romanization of Numidia. Caesar also planned to refound Carthage, and this was effected by Augustus. The number of his original settlers was 3,000, but the colony grew remarkably quickly because of its geographic position favourable for contact with Rome and Italy. A number of other colonies were founded in the interior of Tunisia and at widely separated places on the Mauretanian coasts. In addition, private individuals from Italy immigrated at that time. Veterans founded colonies in Mauretania under the emperor Claudius, including Tingis, Caesarea, and Tipasa. Cuicul (Djemila, Alg.) and Sitifis were founded by Nerva, and Thamugadi and a number of places nearby, in the area north of the Aurès, were founded by Trajan. The army was a potent vehicle in the spread of Roman civilization and played a major part in urbanizing the frontier regions. On limited evidence it has been suggested that a total of some 80,000 immigrants came to the Maghrib from Rome and Italy in this period.

Though at first inferior to the Roman towns, native communities enjoyed the local autonomy that was the hallmark of Roman administration. Between 400 and 500 such communities were recognized, the majority of them villages or small tribal factions. Many, however, advanced in wealth and standing to rival the Roman colonies, acquiring the grant of Roman citizenship, which put the seal of imperial approval on the prosperity, stability, and cultural evolution of developing communities. Naturally, the earliest to show signs of increasing prosperity were the surviving Carthaginian settlements on the coast and places—particularly in the Majardah valley—where the Libyan population had been much influenced by Carthaginian culture and which now also had Italian immigrants. Leptis Magna and Hadrumetum received Roman citizenship and the status of a colony from Trajan, and Thubursicu Numidarum (Khemissa) and Calama (Guelma) in modern Algeria probably the rank of municipality. But it was under Hadrian, the first emperor to visit Africa, that the flood tide of such grants occurred; Utica, Bulla Regia (near Jendouba, Tun.), Lares (Lorbeus, Tun.), Thaenae, and Zama achieved colonial rank, and the process continued throughout the 2nd century. Finally, Septimius Severus, who originated from a wealthy family of Leptis Magna and was of largely mixed descent, became emperor in 193 CE and greatly favoured his native land.

In the Maghrib, Roman rule was not superimposed on established civic aristocracies, as in the Hellenized provinces of Asia Minor, nor on strongly based tribal aristocracies, as in Celtic Gaul. Roman administration and the development of urban society in general depended, apart from immigrants, on the local leadership of small clan and tribal units and on the activity of individuals. In the 1st century CE there were a few large estates owned by absentee Roman senators, most of which were subsequently absorbed into the extensive imperial estate in Africa. The later pattern was of landowning on a more moderate—though still substantial—scale by residents, both immigrant and indigenous. Many landowners made their homes in the towns and formed a local municipal leadership. Small independent landowners also existed, but the great majority of the inhabitants were tenant farmers (coloni). A significant portion of these farmers worked on a sharecropping basis and had labour obligations to their landlords. The number of slave workers was probably smaller than in Italy.

Many of the wealthier Africans entered the imperial administration. The first African consul held office in the reign of Vespasian; at the beginning of the 3rd century, men of African origin held one-sixth of all the posts in the equestrian grade of the administration and also constituted the largest group of provincials in the Senate. It is uncertain what proportion were of native Libyan or mixed origin, but in the 2nd century they were certainly the majority.

During the 2nd and early 3rd centuries the wealthy classes in the towns spent vast sums on their communities in gifts of public buildings such as theatres, baths, and temples, as well as statues, public feasts, and distributions of money. This was a general phenomenon throughout the Roman Empire, as members of local elites competed for fame and prestige among their fellow citizens, but it is particularly well attested in Africa.

The density of the towns in no way implies that trade or industry were predominant; all but a few were residences of both landowners and peasants, and their prosperity depended on agriculture. By the 1st century CE African exports of grain provided two-thirds of the needs of the city of Rome. Some of this, for distribution by the emperors to the urban proletariat, came from the imperial estates and from taxes, but much went to the open market. Annual grain production in Roman Africa has been estimated at more than a million tons, of which one-fourth was exported. Areas of grain production were the Sharīk Peninsula, the Miliana and Majardah valleys, and tracts of relatively level land north of a line from Sitifis to Madauros (M’Daourouch, Alg.). Cereal crops were the most important in these areas, but fruits, such as figs and grapes, and beans also were produced.

The production of olive oil became almost as important as cereals by the 2nd century CE, particularly in southern Tunisia and along the northern slopes of the Aurès and Bou Taleb mountains in Algeria. By the 4th century Africa exported oil to all parts of the empire. Successful cultivation of olives demanded careful management of available water, and the archaeological evidence indicates that much attention was paid to irrigation in the Roman period.

Livestock was an important part of the economy of Roman Africa, though direct evidence is slight. African horses were used in racing and no doubt also in the Roman cavalry. Cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, and mules were also raised. Africa was the major source of the wild animals for shows in Rome and other major cities of the empire—in particular leopards, lions, elephants, and monkeys. Fishing, which had been developed along the coast as far as the Atlantic in the Carthaginian period, continued to flourish. Timber, from the forests along part of the north coast, and marble, the most important North African source of which was Simitthu (Shimṭū, Tun.), were also exported.

There were no large-scale industries, even by ancient standards, in North Africa, except pottery. By the 4th century production of amphorae, necessitated by the oil trade, was substantial, and these and other locally produced wares were traded throughout the Mediterranean. Mosaic pavements were extremely popular among the wealthy throughout North Africa, and more than 2,000 have been discovered, with enormous variations in quality. The majority were made by local craftsmen, though some of the designs originated elsewhere. It is also clear that the building trades were major employers of both skilled and unskilled labour.

An olive harvest in Meknes, Mor.—a city famous for its olive groves—c.1955. Evans/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Prosperity undoubtedly led to a rise in the population of the Maghrib in the first two centuries CE; in the absence of reliable statistics, population estimates have varied from four to eight million (the latter being also the population about the beginning of the 20th century). One study proposed about 6.5 million, of whom about 2.5 million were in present Tunisia. Some two-fifths of the latter (perhaps more) lived in the towns. Of these Carthage was in a class of its own, having at least 250,000 people. The next largest was Leptis Magna (80,000), followed by Hadrumetum, Thysdrus (El-Djem, Tun.), Hippo Regius, and Cirta, with 20,000 to 30,000 each. Many towns in close proximity to each other, especially in the Majardah valley, averaged between 5,000 and 10,000.

The road system in Roman Africa was the most complete of any western province; a total of some 12,500 miles (20,000 km) has been supposed. Most roads were military in origin but were open to commerce, and a number of minor roads linking towns off the main routes were built by the local communities. The main arteries were from Carthage to Theveste, Carthage to Cirta through Sicca Veneria, Theveste to Tacapae through Capsa, Theveste to Lambaesis, Cirta to Sitifis, Cirta to Rusicade, and Cirta to Hippo Regius. Carthage handled by far the greatest volume of overseas official traffic and trade, being the natural port for the wealthiest area of North Africa. Nevertheless, most of the ports originally founded by Phoenicians and Carthaginians expanded during the Roman period; in view of the high costs of land transport, it was natural that agricultural products would go to the nearest port for shipment.

The whole Roman Empire underwent a military and political crisis between the death of Severus Alexander (235 CE) and the accession of Diocletian (284), resulting from serious attacks from outside on the empire’s northern and eastern frontiers and from a series of coups d’état and civil wars. Africa suffered less than most parts of the empire, though there was an unsuccessful revolt by landowners in 238 against the fiscal policies of the emperor Maximinus, which ended in widespread pillage. There were tribal revolts in the Mauretanian mountains in 253–254, 260, and 288, and the situation finally brought a visit from the emperor Maximian in 297–298. The revolts had little effect on the urbanized areas, but the towns were injured by economic difficulties and inflation, and building activity almost ceased. Confidence returned at the end of the 3rd century under Diocletian, Constantine, and later emperors. Administrative changes introduced at this time included the division of the province of Africa into three separate provinces: Tripolitania (capital Leptis Magna), covering the western part of Libya; Byzacena, covering southern Tunisia and governed from Hadrumetum; and the northern part of Tunisia, which retained the name Africa and its capital, Carthage. In addition, the eastern part of Mauretania Caesariensis became a separate province (capital Sitifis). In the far west the Romans gave up much of Mauretania Tingitana, including the important town of Volubilis, apparently because of pressure from the tribe of the Baquates. In the general reorganization of the Roman army by Diocletian and Constantine, the field army (comitatenses) in Africa, numbering on paper some 21,000 men, was put under a new commander, the comes Africae, independent of the provincial governors. Only the governors of Tripolitania and of Mauretania Caesariensis also had troops at their disposal, but these were second-line soldiers, or limitanei. The whole frontier region along the desert and mountain fringes was divided into sectors and garrisoned by limitanei. These were locally recruited and closely identified with the farming population of their areas. The Tripolitanian plateau, which was increasingly exposed to attacks by the nomadic Austuriani, is notable for having a large number of fortified farms.

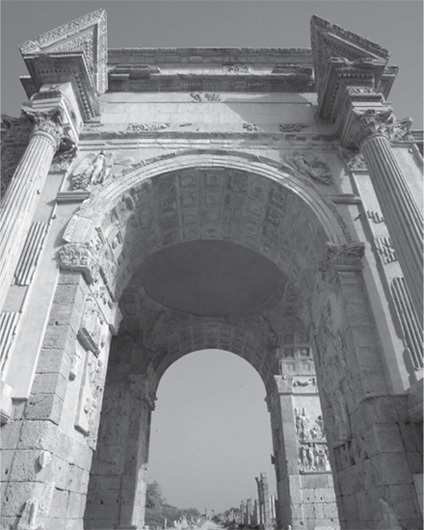

The Arch of Septimius Severus, at the entrance to the Roman citadel of Leptis Magna, Libya. Cris Bouroncle/AFP/Getty Images

Africa, like the rest of the empire, experienced the economic difficulties and governmental pressures that were a feature of the later Roman Empire. The power of the landowners increased at the expense of their tenants and of smaller farmers, both of whom the imperial government sought to bind to the soil in a state of quasi-serfdom. In the cities the tasks of local government that had earlier been eagerly undertaken by the wealthy became burdensome, and again the imperial government sought to make them compulsory and hereditary, while the councillors themselves sought by any means to enter the imperial administration or professions that provided immunity. The process is well attested in Africa. Nevertheless, the view that urban life generally declined throughout the empire during the 4th century must be modified, especially in the case of Africa, where the cities and towns withstood the pressures better than elsewhere and where some towns—Thamugadi, for example—seem to have increased in population. Thamugadi grew doubtlessly because it was relatively immune from damage in civil and external wars and had a solid base of agricultural prosperity.

Christianity grew much more rapidly in Africa than in any other western province. It was firmly established in Carthage and other Tunisian towns by the 3rd century and had produced its own local martyrs and an outstanding apologist in Tertullian (c. 160–240). During the next 50 years it expanded remarkably; more than 80 bishops attended a council at Carthage in 256, some from the distant frontier regions of Numidia. Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage from 248 until his martyrdom in 258, was another figure whose writing, like that of Tertullian, was of lasting influence on Latin Christianity. During the next half-century it spread extensively in Numidia (there were at least 70 bishops in 312). The reasons for its exceptionally rapid growth are disputed. In northern Tunisia urban communities provided a social and economic environment similar to that in which Christianity had first spread in Anatolia and Syria, and much the same can be said about smaller communities in which early Christianity can be identified. It has been held that the intermingling of religious currents of Libyan, Carthaginian, and Roman origin tended toward monotheism, but—even if this were true, which is debatable—pagan monotheism was not a necessary stage toward the adoption of Christianity for more than a few. It does, however, appear that African Christianity always included a vigorous and fanatical element that must have had its effect in spreading the new religion, even though there is little evidence of positive missionary efforts.

Christians were still a minority at the end of the 3rd century in all levels of society, but they were in a good position to benefit from Constantine’s adoption of the religion and his grants of various privileges to the clergy. At that time (313) a division occurred among the African Christians that lasted more than a century. Some Numidian bishops objected to the choice of Caecilian as the new bishop of Carthage, alleging that his ordination had been performed by a bishop who had weakened during Diocletian’s persecution of the church and hence was invalid. They consecrated a rival bishop and, when he died, consecrated another named Donatus, who gave his name to the ensuing schism. The churches in numerous communities, especially in Numidia, followed Donatus from the start and claimed that they alone constituted the true church of the martyrs, who were objects of particularly enthusiastic veneration among African Christians. Among Christians outside Africa, however, Caecilian was universally recognized as the bishop of Carthage, and the emperor Constantine, when the Donatists appealed to him, followed the decisions of non-African church councils, recognizing Caecilian and his followers as the true church and hence as recipients of imperial favour. Some Donatists were killed when their churches were confiscated, the victims being honoured as martyrs, but in 321 Constantine rejected further pressure, and the Donatists continued to increase rapidly in numbers. For the rest of the century, they probably made up half the Christians in North Africa. They were strongest in Numidia and Mauretania Sitifensis, and the antischismatics predominated in the proconsular province of Africa; the position in the Mauretanias was more even, but Christianity did not spread rapidly there until the 5th century. In 347 the emperor Constans exiled a number of Donatist bishops and took repressive measures against the circumcelliones, seasonal farm workers who were particularly enthusiastic Donatists. But in 362 Julian the Apostate allowed the exiles to return. These were welcomed with enthusiasm, and the movement proved as strong as ever. Some Donatists appear to have been associated with the revolt of a Mauretanian chieftain, Firmus, and in 377 the first of a series of general laws proscribing Donatism was issued. Nevertheless, these laws were enforced only sporadically, partly because provincial governors and many local magistrates were still pagan and, at a time of growing weakness in the imperial government, were inclined to ignore instructions they found unwelcome. Donatism was further supported by Gildo, brother of Firmus and comes Africae (387–397). Then Augustine of Hippo Regius applied his enormous powers of leadership and persuasion to stimulate resolute action, evolving at the same time a theory of the right of orthodox Christian rulers to use force against schismatics and heretics. In 411 an imperial commission summoned a conference at Carthage to establish religious unity. The Donatists had to obey, though the decision against them was a foregone conclusion. The laws that followed their condemnation were more generally enforced and, though there was some resistance (some communities still existed in the 6th century), broke the schism as a powerful movement.

Much controversy surrounds the interpretation of Donatism’s significance. An important view considers it in some sense a national or social movement. It is said to have been particularly associated with the rural population of less Romanized areas and with the poorer classes in the towns, whereas orthodox Christianity was the religion of the Romanized upper classes. The imperial government being identified with these Christians would have intensified the strength of the movement, and the circumcelliones’ violence, moreover, could be considered a form of incipient peasant revolt. Thus the movement is claimed as analogous to Monophysitism in Egypt and Syria, which produced a vernacular literature and a passive rejection of Greco-Roman culture. The hostility of the Donatists to the existing society was typified by Donatus’s remark: “What has the emperor to do with the church?” Against this view it may be said that Donatism in the non-Romanized tribal areas was certainly weak, and the relationship of the sect with Firmus and Gildo was of little importance. In Numidia it was at least as strong in the towns as in the rural areas, and in any case the distinction between the two can be exaggerated. The entire controversy was conducted in Latin, and no vernacular literature was produced; in fact, until the time of Augustine, most of the educated class, of the same social background as Augustine himself and fully imbued with Roman tradition, were Donatists if they were not pagan. It was the reluctance of the landowners to have their peasants disturbed, and the negligence of many provincial governors (both attacked by Augustine), that long protected the Donatists. Lastly, in spite of the remark attributed to Donatus, there is no evidence that the movement attacked the imperial system as a whole, as opposed to individual emperors and officials, and it made full use of its many opportunities to defend itself at law both against the other Christians and against divisions in its own ranks.

Nevertheless, although it is difficult to sustain the view that Donatism, especially in Numidia, represented in some way a resurgence of local pre-Roman culture or the speculative, though intriguing, notion that something similar led to the emergence of heretical movements of Islam in the same areas, Donatism certainly appealed to deep-seated traditions of African Christianity. Its fanatical devotion to the memory of martyrs, its doctrinal conservatism, and its total refusal to compromise on its claim to be the true church while its opponents were contaminated by the stain of weakness in the persecutions were fully in line with the heroic days of Tertullian and Cyprian.

The question of whether Roman civilization in the Maghrib was a superficial phenomenon affecting only a small minority of the population who were economically successful, or whether it had profound effects on the majority, is similarly disputed. A priori the former view may be supported by the fact that, whereas Gaul and Spain emerged from the Dark Ages with a language and religion derived from their Roman past, in the Maghrib both disappeared, arguably because they were superficial. It is not disputed that in the mountainous areas, such as the Aurès, Kabylia, and Atlas, native Libyan language and culture continued little affected by Roman civilization, though the majority appear to have been Christian by the 7th century; nor that Libyan and Carthaginian traditions survived in other areas and affected the modes of acceptance of Roman civilization. As regards language, the late form of Phoenician known as Neo-Punic was still spoken fairly widely in the 4th century—for example, in the hills near Hippo Regius. Inscriptions in the language and script occurred often at the beginning of the Roman period but were very rare after the end of the 1st century CE. An exception may be in Tripolitania, where a form of Neo-Punic was inscribed in Latin script perhaps as late as the 4th century. There was also a Libyan script known solely from funerary stelae and akin to the script of the present Tuareg; it was known in some form over much of the Maghrib but may not have been used later than the 3rd century. On the other hand, there is no evidence that these languages were ever literary languages, and the inscriptions are negligible in number compared with those in Latin. It may also be observed that the areas in which Libyan inscriptions occur do not correspond with the later areas of Berber (Amazigh) dialects. The Latin language unquestionably became general through the whole Maghrib, though to a limited extent in the mountains; it is impossible to define any precise social level at which it was unknown. There is a good deal to be said for the view that Christianity, whether Orthodox or Donatist, furthered the use of Latin among elements which up to that time had perhaps still not used it.

The effect of the Donatist controversy on the economy and administration of the African provinces cannot be measured but was certainly profound. At the very moment of the effective victory of the African church, the rest of the Roman Empire was crumbling to ruin. In 406 the Rhine was crossed by Vandals, Alani, Suebi, and others who overran most of Gaul and Spain within the next few years. In 408 Alaric and the Visigoths invaded Italy and in 410 sacked Rome. Although the empire in the west survived for some time longer, the emperors were increasingly at the mercy of their barbarian generals. Meanwhile large tracts of imperial territory were lost as invading tribes settled them. Africa escaped for a while, though only death prevented Alaric from leading the Goths across the Mediterranean. Retaining Africa became ever more vital to the survival of what was left of imperial authority. In this situation the comites Africae (Roman military officials) were increasingly tempted to intrigue for their own advantage. One of them, Bonifacius, is said to have invited the Vandals, who at the time were occupying Andalusia, to his aid, but it is more likely that the Vandals were attracted to Africa by its wealth and needed no such formal excuse. Led by their king Gaiseric, the whole people, 80,000 in all, crossed into Africa in 429 and in the next year advanced with little opposition to Hippo Regius, which they took after a siege during which Augustine died. After defeating the imperial forces near Calama, they overran most of the country, though not all the fortified cities. An agreement made in 435 allotted Numidia and Mauretania Sitifensis to the Vandals, but in 439 Gaiseric took and pillaged Carthage and the rest of the province of Africa. A further treaty with the imperial government (442) established the Vandals in Africa Proconsularis, Byzacena, Tripolitania, and Numidia as far west as Cirta.

Although the Vandals were probably no more deliberately destructive than other Germanic invaders (the notion of “vandalism” stems from the 18th century), their establishment had strong adverse effects. The imperial authorities had to reduce the taxes of the Mauretanias by seven-eighths after they were devastated. Over much of northern Tunisia, landowners were expelled and their properties handed over to Vandals. Although the agricultural system remained based on the peasants, the expulsions had a serious effect on the towns with which the landowners had been connected. The Vandals, like other invading tribes except the Franks, were divided from their subjects by their Arianism. Although their persecution of Latin Christians was exaggerated by the latter, Vandal kings certainly exercised more pressure than others. This was no doubt in response to the vigour of African Christianity, which kept the loyalty even of those who had little to lose by the substitution of a Vandal for a Roman landlord.

Gaiseric was perhaps the most perceptive barbarian king of the 5th century in realizing the total weakness of the empire. He rejected the policy of formal alliance with it and from 455 used his large merchant fleet to dominate the western Mediterranean. Rome was sacked, the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia, and part of Sicily were occupied, and the coasts of Dalmatia and Greece were plundered. Although trade continued, Gaiseric’s actions accelerated the breakup of the economic unity of the western Mediterranean, which already was being threatened by the creation of the other barbarian kingdoms. Gaiseric’s successors were less formidable: Huneric (477–484) launched a general persecution of the Latin church, apparently from genuine religious fanaticism rather than for political reasons, but his successor adopted a milder policy. Later, under Thrasamund (496–523), there is evidence that many Vandals adopted Roman culture, but the tribe retained its identity until the Byzantine reconquest.

A significant development of the Vandal period was that independent kingdoms, largely of Libyan character, emerged in the mountainous and desert areas. They appeared first in the Mauretanias, where the Roman frontier, already drawn back under Diocletian, receded further under the Vandal kings. By the end of Vandal rule, independent kingdoms existed in the region of Altava (Oulad Mimoun), in the Ouarsenis Mountains, and in the Hodna region (in present-day Algeria). After 480, towns to the north of the Aurès Mountains, such as Thamugadi, Bagai, and Theveste, were sacked by the inhabitants of another kingdom in the Aurès. All the names of the known chieftains are Libyan in character, though the survival of Romanized elements within some of the kingdoms is attested by the fact that epitaphs in Latin continued, Roman names were still used, and a dating system based on the founding date of the Roman province of Mauretania was even maintained. Finally, as a harbinger of a serious threat to settled life, whether Roman or Libyan, tribes that had retained a nomadic way of life on the borders of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania and caused much damage in the 4th century began to push westward and were already a serious threat to the southern parts of Byzacena by the end of Vandal rule.

North Africa held an important place in the emperor Justinian’s scheme for reuniting the Roman Empire and destroying the Germanic kingdoms. His invasion of Africa was undertaken against the advice of his experts (an earlier attempt in 468 had failed disastrously), but his general Belisarius succeeded, partly through Vandal incompetence. He landed in 533 with only 16,000 men, and within a year the Vandal kingdom was destroyed. A new administrative structure was introduced, headed by a praetorian prefect with six subordinate governors for civil matters and a master of soldiers with four subordinate generals.

Arianism is a Christian heresy that affirmed that Christ is not truly divine but a created being. It was first proposed early in the 4th century by the Alexandrian presbyter Arius. His basic premise was the uniqueness of God, who is alone self-existent and immutable; the Son, who is not self-existent, cannot be God. Because the Godhead is unique, it cannot be shared or communicated, so the Son cannot be God. Because the Godhead is immutable, the Son, who is mutable, being represented in the Gospels as subject to growth and change, cannot be God. The Son must, therefore, be deemed a creature who has been called into existence out of nothing and has had a beginning. Moreover, the Son can have no direct knowledge of the Father since the Son is finite and of a different order of existence.

According to its opponents, especially the bishop Athanasius, Arius’ teaching reduced the Son to a demigod, reintroduced polytheism (since worship of the Son was not abandoned), and undermined the Christian concept of redemption since only he who was truly God could be deemed to have reconciled man to the Godhead.

It required a dozen years, however, to pacify Africa, partly because of tribal resistance in Mauretania to an ordered government being reestablished and partly because support to the army in men and money was poor, leading to frequent mutinies. A remarkable program of fortifications—many of which survive—was rapidly built under Belisarius’s successor Solomon. Some were garrison forts in the frontier region, which again seems to have extended, at least for a while, south of the Aurès and then northward from Tubunae to Saldae. But many surviving towns in the interior were also equipped with substantial walls—e.g., Thugga and Vaga (Béja, Tun.). There were further difficulties with the Mauretanian tribes (the Mauri) after Justinian died (565), but the most serious damage was done by the nomadic Louata from the Libyan Desert, who on several occasions penetrated far into Tunisia.

Africa shows a number of examples of the massive help given by Justinian in building—and particularly decorating—churches and in reestablishing Christian orthodoxy, though surviving Donatists were inevitably persecuted. Seriously weakened though it had been under the Vandals, the African church retained some traces of its vigour when it led the opposition of the Western churches to the theological policies of emperors at Constantinople—e.g., those of Justinian himself and also of Heraclius and Constans II immediately before the Arab invasions.

Little is known of the Byzantine period in the Maghrib after the death of Justinian. The power of the military element in the provinces grew, and in the late 6th century a new official, the exarch, was introduced whose powers were almost viceregal. Economic conditions declined because of the increasing insecurity and also the notorious corruption and extortion of the administration, though whether this was worse in Africa than in other parts of the Byzantine Empire is impossible to say. It is certain that the population of the towns was only a small proportion of what it had been in the 4th century. The court of Constantinople tended to neglect Africa because of the more immediate dangers on the eastern and Balkan frontiers. Only once in its latest phase was it the scene of an important historical event; in 610 Heraclius, son of the African exarch at the time, sailed from Carthage to Constantinople in a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas and succeeded him the same year. That Africa was still of some importance to the empire was shown in 619; the Persians had overrun much of the east, including Egypt, and only Africa appeared able to provide money and recruits. Heraclius even thought of leaving Constantinople for Carthage but was prevented by popular feeling in the capital.

In view of the lack of evidence for the Byzantine period, and the still greater obscurity surrounding the period of Arab raids and conquest (643–698) and its immediate aftermath, conclusions on the state of the Maghrib at the end of Byzantine rule are speculative. Much of it was in the hands of tribal groups, among which the level of Roman culture was in many cases no doubt negligible. Even before the Arab attacks began, the picture seems to be one of a continual ebb of Latin civilization and the Latin language from all of the Maghrib except along the coastal fringes of Tunisia, and the development and expansion of larger tribal groupings, some, though not all, of which were Christian. Also, the Byzantine administration was, in a sense, foreign to the Latin population. The military forces sent from Constantinople to stem the invasion were ultimately inadequate, though Arab conquest of the region could not be secure until Carthage was captured and destroyed and reinforcements by sea interdicted. The most determined resistance to the Arabs came from nomadic Libyan tribes living in the area around the Aurès Mountains. Destruction in the settled areas in the earlier attacks, which were little more than large-scale raiding expeditions, was certainly immense. It has been held that town life and even an ordered agricultural system almost disappeared at that time, though some scholars believe that a modicum of these survived until the invasions of larger nomadic groups, in particular the Banū Hilāl, in the 11th century. Latin was still in use for Christian epitaphs at El-Ngila in Tripolitania and even at Kairouan (Al-Qayrawān) in the 10th and 11th centuries. However, throughout the Maghrib the conversion of various population groups to Islam rapidly Arabized most of the region in language and culture, though the modalities of these profound changes remain obscure.

Belgian scholar Henri Pirenne formulated a theory, widely discussed, that the essential break between the ancient and medieval European worlds came when the unity of the Mediterranean was destroyed not by the Germanic but by the Arab invasions. The history of the Maghrib is an important element in this debate, for there one can see the complete replacement of a centuries-old political, social, religious, and cultural system by another within a short span of time.

Much of the Roman period in Cyrenaica was peaceful. Some Roman immigrants resided there at an early date, and some of the Greeks received Roman citizenship. A famous inscription of 4 BCE contains a number of edicts of the emperor Augustus regulating with great fairness the relationship between Roman and non-Roman. The character of its civilization, however, remained entirely Greek. Jews formed a considerable minority group in the province and had their own organizations at Berenice and Cyrene. They took no part in the great revolt of Judaea in 66 CE but in 115 began a formidable rebellion in Cyrene that spread to Egypt. No reason for it is known. It caused great destruction and loss of life, and Hadrian took special measures to reconstruct Cyrene and also sent out some colonists. Peaceful conditions returned, but in 268–269 the Marmaridae, inhabiting the coast between Cyrenaica and Egypt, caused trouble. When Diocletian reorganized the empire, Cyrenaica was separated from Crete and divided into two provinces: Libya Superior, or Pentapolis (capital Ptolemais), and Libya Inferior, or Sicca (capital Paraetonium [Marsā Maṭrūḥ, Egypt]). A regular force was stationed there for the first time under a dux Libyarum. At the end of the 4th century, the Austuriani, a nomad tribe that had earlier raided Tripolitania, caused much damage, and Cyrenaica began to suffer from the general decline of security throughout the empire, in this case from desert nomads. A notable phenomenon of the 5th and 6th centuries, as in Tripolitania, was the number of fortified farms, most frequent in the Akhḍar Mountains and south of Boreum (Bū Quraydah) and also apparently in the region of Banghāzī.

Christianity no doubt spread to Cyrenaica from Egypt. In the 3rd century the bishop of Ptolemais was metropolitan, but by the 4th century the powerful bishops of Alexandria consecrated the local bishops. The best-known Cyrenaican is Synesius, a citizen of Cyrene with philosophic tastes who was made bishop of Ptolemais in 410 partly because of his ability to obtain help for his province from the imperial authorities. Under Justinian a number of defensive works were constructed as elsewhere in Africa—e.g., Taucheira, Berenice, Antipyrgos (Tobruk), and Boreum. Recent excavations of a series of churches reveal the expenditure he devoted to their beautification, in what was a province of minor importance. On the eve of the Arab conquest (643), the general condition of Cyrenaica would appear to have been on a par with most of the other eastern provinces of the empire.