Libya is located along the Mediterranean coast of northern Africa. The modern-day country became independent in 1951. The capital is Tripoli.

Largely desert with some limited potential for urban and sedentary (non-migratory) life in the northwest and northeast, Libya has historically never been heavily populated nor has it been a power centre. Like that of its neighbour Algeria, Libya’s very name is a neologism, created by the conquering Italians early in the 20th century. Also like that of Algeria, much of Libya’s earlier history—not only in the Islamic period but even before—reveals that both Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were more closely linked with neighbouring territories Tunisia and Egypt, respectively, than with each other. Even during the Ottoman era, the country was divided into two parts, one linked to Tripoli in the west and the other to Banghāzī in the east.

Libya thus owes its present unity as a state less to earlier history or geographic characteristics than to several recent factors: the unifying effect of the Sanūsiyyah movement since the 19th century; Italian colonialism from 1911 until after World War II; an early independence by default, since the great powers could agree on no other solution; and the discovery of oil in commercial quantities in the late 1950s. Yet the Sanūsiyyah is based largely in the eastern region of Cyrenaica and has never really penetrated the more populous northwestern region of Tripolitania. Italian colonization was brief and brutal. Moreover, most of the hard-earned gains in infrastructure implanted during the colonial period were destroyed by contending armies during World War II. Sudden oil wealth has been both a boon and a curse as changes to the political and social fabric—as well as to the economy—have accelerated. This difficult legacy of disparate elements and forces helps to explain the unique character of present-day Libya.

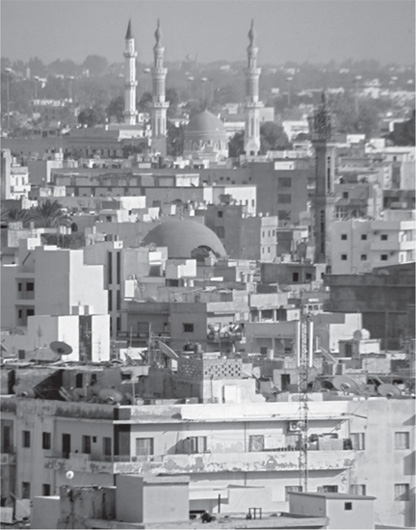

Downtown Tripoli, Libya, 2004. John MacDougall/AFP/Getty Images

Part of the Ottoman Empire from the early 16th century, Libya experienced autonomous rule (analogous to that in Ottoman Algeria and Tunisia) under the Karamanli dynasty from 1711 to 1835. In the latter year the Ottomans took advantage of a succession dispute and local disorder to reestablish direct administration. For the next 77 years the area was administered by officials from the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) and shared in the limited modernization common to the rest of the empire. In Libya the most significant event of the period was the foundation in 1837 of the Sanūsiyyah, an Islamic order, or fraternity, that preached a puritanical form of Islam, giving the people instruction and material assistance and so creating among them a sense of unity. The first Sanūsī zāwiyah (monastic complex) in Libya was established in 1843 near the ruins of Cyrene in eastern Cyrenaica. The order spread principally in that province but also found adherents in the south. The Grand al-Sanūsī, as the founder came to be called, moved his headquarters to the oasis of Al-Jaghbūb near the Egyptian frontier, and in 1895 his son and successor, Sīdī Muḥammad Idrīs al-Mahdī, transferred it farther south into the Sahara to the oasis group of Al-Kufrah. Though the Ottomans welcomed the order’s opposition to the spread of French influence northward from Chad and Tibesti, they regarded with suspicion the political influence it exerted within Cyrenaica. In 1908 the Young Turk revolution gave a new impulse to reform; in 1911, however, the Italians, who had banking and other interests in the country, launched an invasion.

The Ottomans sued for peace in 1912, but Italy found it more difficult to subdue the local population. Resistance to the Italian occupation continued throughout World War I. After the war Italy considered coming to terms with nationalist forces in Tripolitania and with the Sanūsiyyah, which was strong in Cyrenaica. These negotiations foundered, however, and the arrival of a strong governor, Giuseppe Volpi, in Libya and a Fascist government in Italy (1922) inaugurated an Italian policy of thorough colonization. The coastal areas of Tripolitania were subdued by 1923, but in Cyrenaica Sanūsī resistance, led by ‘Umar al-Mukhtār, continued until his capture and execution in 1931.

In the 1920s and ’30s the Italian government expended large sums on developing towns, roads, and agricultural colonies for Italian settlers. The most ambitious effort was the program of Italian immigration called “demographic colonization,” launched by the Fascist leader Benito Mussolini in 1935. As a result of these efforts, by the outbreak of World War II, some 150,000 Italians had settled in Libya and constituted roughly one-fifth of that country’s total population.

These colonizing efforts and the resulting economic development of Libya were largely destroyed during the North Africa campaigns of 1941–43. Cyrenaica changed hands three times, and by the end of 1942 all of the Italian settlers had left. Cyrenaica largely reverted to pastoralism. Economic and administrative development fostered by Italy survived in Tripolitania; however, Libya by 1945 was impoverished, underpopulated, and also divided into regions—Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan—of differing political, economic, and religious traditions.

The future of Libya gave rise to long discussions after the war. In view of the contribution to the fighting made by a volunteer Sanūsī force, the British foreign minister pledged in 1942 that the Sanūsīs would not again be subjected to Italian rule. During the discussions, which lasted four years, suggestions included an Italian trusteeship, a UN trusteeship, a Soviet mandate for Tripolitania, and various compromises. Finally, in November 1949, the UN General Assembly voted that Libya should become a united and independent kingdom no later than Jan. 1, 1952.

A constitution creating a federal state with a separate parliament for each province was drawn up, and the pro-British head of the Sanūsiyyah, Sīdī Muḥammad Idrīs al-Mahdī al-Sanūsī, was chosen king by a national assembly in 1950. On Dec. 24, 1951, King Idris I declared the country independent. Political parties were prohibited, and the king’s authority was sovereign. Though not themselves Sanūsīs, the Tripolitanians accepted the monarchy largely in order to profit from the British promise that the Sanūsīs would not again be subjected to Italian rule. King Idris, however, showed a marked preference for living in Cyrenaica, where he built a new capital on the site of the Sanūsī zāwiyah at Al-Bayḍā’. Though Libya joined the Arab League in 1953 and in 1956 refused British troops permission to land during the Suez Crisis, the government in general adopted a pro-Western position in international affairs.

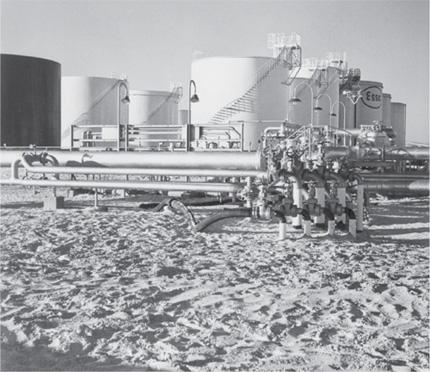

With the discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959, Libya changed abruptly from being dependent on international aid and the rent from U.S. and British air bases to being an oil-rich monarchy. Major petroleum deposits in both Tripolitania and Cyrenaica ensured the country income on a vast scale. The discovery was followed by an enormous expansion in all government services, massive construction projects, and a corresponding rise in the economic standard and the cost of living.

This photograph, c. 1960, shows the Esso Standard Libya Inc. storage facility at the Zalṭan and Al-Rāqūbah (Raguba) refinery and pipeline terminal. Zalṭan, part of an “oasis” of regional oil fields, was the site of the first exploited oil field in Libya. Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Precipitated by the king’s failure to speak out against Israel during the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War (June War) in 1967, a coup was carried out on Sept. 1, 1969, by a group of young army officers led by Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi, who deposed the king and proclaimed Libya a republic. The new regime, passionately Pan-Arab, broke the monarchy’s close ties to Britain and the United States and also began an assertive policy that led to higher oil prices along with 51 percent Libyan participation in oil company activities and, in some cases, outright nationalization.

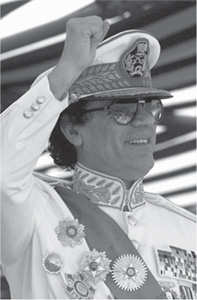

(b. 1942, near Surt, Libya)

Muammar al-Qaddafi (also spelled Muammar Khadafy, Moammar Gadhafi, or Mu‘ammar al-Qadhdhāfī) has been the de facto leader of Libya from 1969. He has been active in both Arab and African intergovernmental affairs.

The son of an itinerant Bedouin farmer, Qaddafi was born in a tent in the Libyan desert. He proved a talented student and graduated from the University of Libya in 1963. A devout Muslim and ardent Arab nationalist, Qaddafi early began plotting to overthrow the Libyan monarchy of King Idris I. He graduated from the Libyan military academy in 1965 and thereafter rose steadily through the ranks, all the while continuing to plan a coup with the help of his fellow army officers. On Sept. 1,1969, Qaddafi seized control of the government in a military coup that deposed King Idris. Qaddafi was named commander in chief of the armed forces and chairman of Libya’s new governing body, the Revolutionary Command Council.

Qaddafi removed the U.S. and British military bases from Libya in 1970. He expelled most members of the native Italian and Jewish communities from Libya that same year, and in 1973 he nationalized all foreign-owned petroleum assets in the country. He also outlawed alcoholic beverages and gambling, in accordance with his own strict Islamic principles. Qaddafi also began a series of persistent but unsuccessful attempts to unify Libya with other Arab countries. He was adamantly opposed to negotiations with Israel and became a leader of the so-called rejectionist front of Arab nations in this regard. He also earned a reputation for military adventurism; his government was implicated in several abortive coup attempts in Egypt and Sudan, and Libyan forces persistently intervened in the long-running civil war in neighbouring Chad.

From 1974 onward Qaddafi espoused a form of Islamic socialism as expressed in his The Green Book. This combined the nationalization of many economic sectors with a brand of populist government ostensibly operating through people’s congresses, labour unions, and other mass organizations. Meanwhile, Qaddafi was becoming known for his erratic and unpredictable behaviour on the international scene. His government financed a broad spectrum of revolutionary or terrorist groups worldwide, including the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam in the United States and the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland. Squads of Libyan agents assassinated émigré opponents abroad, and his government was allegedly involved in several bloody terrorist incidents in Europe perpetrated by Palestinian or other Arab extremists. These activities brought him into growing conflict with the U.S. government, and in April 1986 a force of British-based U.S. warplanes bombed several sites in Libya, killing or wounding several of his children and narrowly missing Qaddafi himself.

Libya’s purported involvement in the destruction of a civilian airliner over Lockerbie, Scot., in 1988, led to United Nations and U.S. sanctions that further isolated Qaddafi from the international community. In the late 1990s, however, Qaddafi turned over the alleged perpetrators of the bombing to international authorities. UN sanctions against Libya were subsequently lifted in 2003, and, following Qaddafi’s announcement that Libya would cease its unconventional-weapons program, the United States dropped most of its sanctions as well. Although some observers remained critical— particularly when, in 2009, Qaddafi warmly welcomed convicted Lockerbie bomber ‘Abd al-Basit al-Magrahi back home to Libya (Megrahi had been released on compassionate grounds owing to his terminal cancer)—the lifting of sanctions nevertheless provided an opportunity for the rehabilitation of Qaddafi’s image abroad, facilitating his country’s gradual return to the global community.

In February 2009 Qaddafi was elected chairman of the African Union (AU), and later that year he gave his first speech before the UN General Assembly. The lengthy critical speech, in which he threw a copy of the UN charter, generated a significant measure of controversy within the international community. In early 2010 Qaddafi’s attempt to remain as chairman of the AU beyond the customary one-year term was met with resistance from several other African countries and ultimately was denied.

Equally assertive in plans for Arab unity, Libya obtained at least the formal beginnings of unity with Egypt, Sudan, and Tunisia, but these and other such plans failed as differences arose between the governments concerned. Qaddafi’s Libya supported the Palestinian cause and intervened to support it, as well as other guerrilla and revolutionary organizations in Africa and the Middle East. Such moves alienated the Western countries and some Arab states. In July–August 1977 hostilities broke out between Libya and Egypt, and, as a result, many Egyptians working in Libya were expelled. Indeed, despite expressed concern for Arab unity, the regime’s relations with most Arab countries deteriorated. Qaddafi signed a treaty of union with Morocco’s King Hassan II in August 1984, but Hassan abrogated the treaty two years later.

The regime, under Qaddafi’s ideological guidance, continued to introduce innovations. On March 2, 1977, the General People’s Congress declared that Libya was to be known as the People’s Socialist Libyan Arab Jamāhīriyyah (the latter term is a neologism meaning “government through the masses”). By the early 1980s, however, a drop in the demand and price for oil on the world market was beginning to hamper Qaddafi’s efforts to play a strong regional role. Ambitious efforts to radically change Libya’s economy and society slowed, and there were signs of domestic discontent. Libyan opposition movements launched sporadic attacks against Qaddafi and his military supporters but met with arrest and execution.

Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi, 1999. Marwan Naamani—AFP/Getty Images

Libya’s relationship with the United States, which had been an important trading partner, deteriorated in the early 1980s as the U.S. government increasingly protested Qaddafi’s support of Palestinian Arab militants. An escalating series of retaliatory trade restrictions and military skirmishes culminated in a U.S. bombing raid of Tripoli and Banghāzī in 1986, in which Qaddafi’s adopted daughter was among the casualties. U.S. claims that Libya was producing chemical warfare materials contributed to the tension between the two countries in the late 1980s and ’90s. Within the region, Libya sought throughout the 1970s and ’80s to control the mineral-rich Aozou strip along the disputed border with neighbouring Chad. These efforts produced intermittent warfare in Chad and confrontation with both France and the United States. In 1987 Libyan forces were bested by Chad’s more mobile troops, and diplomatic ties with that country were restored late the following year. Libya denied involvement in Chad’s December 1990 coup led by Idrīss Déby.

In 1996 the United States and the UN implemented a series of economic sanctions against Libya for its purported involvement in destroying a civilian airliner over Lockerbie, Scot., in 1988. In the late 1990s, in an effort to placate the international community, Libya turned over the alleged perpetrators of the bombing to international authorities and accepted a ruling by the international court in The Hague stating that the contested Aozou territory along the border with Chad belonged to that country and not to Libya. The United Kingdom restored diplomatic relations with Libya at the end of the decade, and UN sanctions were lifted in 2003; later that year Libya announced that it would stop producing chemical weapons. The United States responded by dropping most of its sanctions, and the restoration of full diplomatic ties between the two countries was completed in 2006. In 2007 five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor who had been sentenced to death in Libya after being tried on charges of having deliberately infected children there with HIV were extradited to Bulgaria and quickly pardoned by its president, defusing widespread outcry over the case and preventing the situation from posing an obstacle to Libya’s return to the international community.

In the years that followed the lifting of sanctions, one of Qaddafi’s sons, Sayf al-Islam al-Qaddafi, emerged as a proponent of reform and helped lead Libya toward adjustments in its domestic and foreign policy. Measures including efforts to attract Western business and plans to foster tourism promised to gradually draw Libya more substantially into the global community.