Morocco is a country on the Atlantic coast of northwestern Africa. The modern-day country became independent in 1956. The capital is Rabat.

Situated in the northwest corner of Africa and, on a clear day, visible from the Spanish coast, Morocco has resisted outside invasion while serving as a meeting point for European, Eastern, and African civilizations throughout history. Its early inhabitants were Tamazight-speaking nomads; many of these became followers of Christianity and Judaism, which were introduced during a brief period of Roman rule. In the late 7th century, Arab invaders from the East brought Islam, which local Imazighen gradually assimilated. Sunni Islam triumphed over various sectarian tendencies in the 12th and 13th centuries under the doctrinally rigorous Almohad dynasty. The Christian reconquest of Spain in the later Middle Ages brought waves of Muslim and Jewish exiles from Spain to Morocco, injecting a Hispanic flavour into Moroccan urban life. Apart from some isolated coastal enclaves, however, Europeans failed to establish a permanent foothold in the area. In the 16th century, Ottoman invaders from Algeria attempted to add Morocco to their empire, thus threatening the country’s independence. They, too, were thwarted, leaving Morocco virtually the only Arab country never to experience Ottoman rule. In 1578, three kings fought and died near Ksar el-Kebir (Alcazarquivir), including the Portuguese monarch Sebastian. This decisive battle, known as the Battle of the Three Kings, was claimed as a Moroccan victory and put an end to European incursions onto Moroccan soil for three centuries. The 17th century saw the rise of the ‘Alawite dynasty of sharifs, who still rule Morocco today. This dynasty fostered trade and cultural relations with sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and the Arab lands, though religious tensions between Islam and Christendom often threatened the peace.

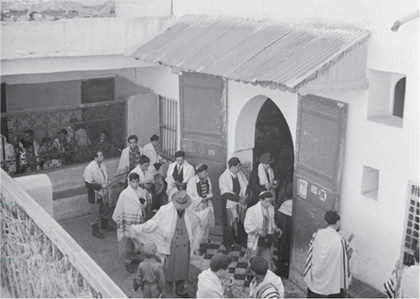

Sabbath services at a Moroccan synagogue, c. 1955. Evans/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

By the late 17th century, Morocco’s cultural and political identity as an Islamic monarchy was firmly established. The figure of the strong sultan was personified by Mawlāy Ismā‘īl (1672–1727), who used a slave army, known as the ‘Abīd al-Bukhārī, to subdue all parts of the country and establish centralized rule. Subsequent monarchs often used their prestige as religious leaders to contain internal conflicts caused by competition among tribes. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when Europe was preoccupied with revolution and continental war, Morocco withdrew into a period of isolation. On the eve of the modern era, despite their geographic proximity, Moroccans and Europeans knew little about each other.

The ‘Abīd al-Bukhārī, also known as the Buākhar, was an army of Saharan blacks organized in Morocco by the ‘Alawī ruler Ismā‘īl (reigned 1672–1727). Earlier rulers had recruited black slaves (Arabic: ‘abīd) into their armies, and these men or their descendants eventually formed the core of Ismā‘īl’s guard.

The ‘abīd were sent to a special camp at Mechra‘ er-Remel to beget children. The communal children, male and female, were presented to the ruler when they were about 10 years old and proceeded to a prescribed course of training. The boys acquired such skills as masonry, horsemanship, archery, and musketry, whereas the girls were prepared for domestic life or for entertainment. At the age of 15 they were divided among the various army corps and married, and eventually the cycle would repeat itself with their children.

Ismā‘īl’s army, numbering 150,000 men at its peak, consisted mainly of the “graduates” of the Mechra‘ er-Remel camp and supplementary slaves pirated from black Saharan tribes, all foreigners whose sole allegiance was to the ruler. The ‘abīd were highly favoured by Ismā‘īl, well paid, and often politically powerful; in 1697–98 they were even given the right to own property.

After Ismā‘īl’s death the quality of the corps could not be sustained. Discipline slackened, and, as preferential pay was no longer forthcoming, the ‘abīd took to brigandage. Many left their outposts and shifted into the cities, and others became farmers or peasants. Those who remained in the army were an unstable element, ready for intrigue. Under strong rulers, the ‘Abīd al-Bukhārī were periodically reorganized, though never regaining their former military and numerical strength. The ‘abīd were finally dissolved late in the 19th century, with only a nominal number retained as the king’s personal bodyguard.

During the French invasion of Algeria in 1830, the sultan of Morocco, Mawlāy ‘Abd al-Raḥmān (1822–59), briefly sent troops to occupy Tlemcen but withdrew them after French protests. The Algerian leader Abdelkader in 1844 took refuge from the French in Morocco. A Moroccan army was sent to the Algerian frontier; the French bombarded Tangier on Aug. 4, 1844, and Essaouira (Mogador) on August 15. Meanwhile, on August 14, the Moroccan army had been totally defeated at Isly, near the frontier town of Oujda. The sultan then promised to intern or expel Abdelkader if he should again enter Moroccan territory. Two years later, when he was again driven into Morocco, the Algerian leader was attacked by Moroccan troops and was forced to surrender to the French.

Immediately after ‘Abd al-Raḥmān’s death in 1859, a dispute with Spain over the boundaries of the Spanish enclave at Ceuta led Madrid to declare war. Spain captured Tétouan in the following year. Peace had to be bought with an indemnity of $20 million, the enlargement of Ceuta’s frontiers, and the promise to cede to Spain another enclave—Ifni.

The new sultan, Sīdī Muḥammad, attempted with little success to modernize the Moroccan army. Upon his death in 1873, his son Mawlāy Hassan I struggled to preserve independence. Hassan I died in 1894, and his chamberlain, Bā Aḥmad (Aḥmad ibn Mūsā), ruled in the name of the young sultan ‘Abd al-‘Azīz until 1901, when the latter began his direct rule.

‘Abd al-‘Azīz surrounded himself with European companions and adopted their customs, while scandalizing his own subjects, particularly the religious leaders. His attempt to introduce a modern system of land taxation resulted in complete confusion because of a lack of qualified officials. Popular discontent and tribal rebellion became even more common, while a pretender, Bū Ḥmāra (Abū Ḥamārah), established a rival court near Melilla. European powers seized the occasion to extend their own influence. In 1904 Britain gave France a free hand in Morocco in exchange for French noninterference with British plans in Egypt. Spanish agreement was secured by a French promise that northern Morocco should be treated as a sphere of Spanish influence. Italian interests were satisfied by France’s decision not to hinder Italian designs on Libya. Once these various interests were settled, the Western powers met with Moroccan representatives at Algeciras, Spain, in 1906, to discuss the country’s future.

The Algeciras Conference confirmed the integrity of the sultan’s domains but sanctioned French and Spanish policing Moroccan ports and collecting the customs dues. In 1907–08 the sultan’s brother, Mawlāy ‘Abd al-Ḥāfiẓ, led a rebellion against him from Marrakech, denouncing ‘Abd al-‘Azīz for his collaboration with the Europeans. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz subsequently fled to distant Tangier. ‘Abd al-Ḥāfiẓ then made an abortive attack on French troops, which had occupied Casablanca in 1907, before proceeding to Fès, where he was duly proclaimed sultan and recognized by the European powers (1909).

The new sultan proved unable to control the country. Disorder increased until, besieged by tribesmen in Fès, he was forced to ask the French to rescue him. When they had done so, he had no choice but to sign the Treaty of Fez (March 30, 1912), by which Morocco became a French protectorate. In return, the French guaranteed that the status of the sultan and his successors would be maintained. Provision was also made to meet the Spanish claim for a special position in the north of the country; Tangier, long the seat of the diplomatic missions, retained a separate administration.

In establishing their protectorate over much of Morocco, the French had behind them the experience of the conquest of Algeria and of their protectorate over Tunisia; they took the latter as the model for their Moroccan policy. There were, however, important differences. First, the protectorate was established only two years before the outbreak of World War I, which brought with it a new attitude toward colonial rule. Second, Morocco had a thousand-year tradition of independence; though it had been strongly influenced by the civilization of Muslim Spain, it had never been subject to Ottoman rule. These circumstances and the proximity of Morocco to Spain created a special relationship between the two countries.

Morocco was also unique among the North African countries in possessing a coast on the Atlantic, in the rights that various nations derived from the Act of Algeciras, and in the privileges that their diplomatic missions had acquired in Tangier. Thus, the northern tenth of the country, with both Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, together with the desert province of Tarfaya in the southwest adjoining the Spanish Sahara, were excluded from the French-controlled area and treated as a Spanish protectorate. In the French zone, the fiction of the sultan’s sovereignty was maintained, but the French-appointed resident general held the real authority and was subject only to the approval of the government in Paris. The sultan worked through newly created departments staffed by French officials. The negligible role that the Moroccan government (makhzan) actually played can be seen by the fact that Muḥammad al-Muqrī, the grand vizier when the protectorate was installed, held the same post when Morocco recovered its independence 44 years later; he was by then more than 100 years old. As in Tunisia, country districts were administered by contrôleurs civils, except in certain areas such as Fès, where it was felt that officers of the rank of general should supervise the administration. In the south certain Amazigh chiefs (qā’ids), of whom the best known was Thami al-Glaoui, were given a great deal of independence.

The first resident general, Gen. (later Marshal) Louis-Hubert-Gonzalve Lyautey, was a soldier of wide experience in Indochina, Madagascar, and Algeria. He was of aristocratic outlook and possessed a deep appreciation of Moroccan civilization. The character he gave to the administration exerted an influence throughout the period of the protectorate.

Lyautey’s idea was to leave the Moroccan elite intact and rule through a policy of cooptation. He placed ‘Abd al-Ḥāfiẓ’s more amenable brother, Mawlāy Yūsuf, on the throne. This sultan succeeded in cooperating with the French without losing the respect of the Moroccan people. A new administrative capital was created on the Atlantic coast at Rabat, and a commercial port subsequently was developed at Casablanca. By the end of the protectorate in 1956, Casablanca was a flourishing city, with nearly a million inhabitants and a substantial industrial establishment. Lyautey’s plan to build new European cities separate from the old Moroccan towns left the traditional medinas intact. Remarkably, World War I did little to interrupt this rhythm of innovation. Though the French government had proposed retiring to the coast, Lyautey managed to retain control of all the French-occupied territory.

After the war Morocco faced two major problems. The first was pacifying the outlying areas in the Atlas Mountains, over which the sultan’s government often had had no real control; this was finally completed in 1934. The second problem was the spread of the uprising of Abd el-Krim from the Spanish to the French zone, which was quelled by French and Spanish troops in 1926. That same year, Marshal Lyautey was succeeded by a civilian resident general. This marked a change to a more conventional colonial-style administration, accompanied by official colonization, the growth of the European population, and the increasing impact of European thought on the younger generation of Moroccans, some of whom had by then received a French education.

As early as 1920 Lyautey had submitted a report saying that “a young generation is growing up which is full of life and needs activity…. Lacking the outlets which our administration offers only sparingly and in subordinate positions they will find an alternative way out.” Only six years after Lyautey’s report, young Moroccans both in Rabat, the new administrative capital, and in Fès, the centre of traditional Arab-Islamic learning and culture, were meeting independently of one another to discuss demands for reforms within the terms of the protectorate treaty. They asked for more schools, a new judicial system, and the abolition of the regime of the Amazigh qā’ids in the south; for study missions in France and the Middle East; and for the cessation of official colonization—objectives that would be fully secured only when the protectorate ended in 1956.

On the death of Mawlāy Yūsuf (1927) the French chose as his successor his younger son, Sīdī Muḥammad (Muḥammad V). Selected in part for his retiring disposition, this sultan eventually revealed considerable diplomatic skill and determination. Also significant was the French attempt to use the purported differences between Arabs and Imazighen to undercut any growing sense of national unity. This led the French to issue the Berber Decree in 1930, which was a crude effort to divide Imazighen and Arabs. The result was just the opposite of French intentions; it provoked a Moroccan nationalist reaction and forced the administration to modify its proposals. In 1933 the nationalists initiated a new national day called the Fête du Trône (Throne Day) to mark the anniversary of the sultan’s accession. When he visited Fès the following year, the sultan received a tumultuous welcome, accompanied by anti-French demonstrations that caused the authorities to terminate his visit abruptly. Shortly after this episode political parties were organized that sought greater Moroccan self-rule. These events coincided with the completion of the French occupation of southern Morocco, which paved the way for the Spanish occupation of Ifni. In 1937 rioting occurred in Meknès, where French settlers were suspected of diverting part of the town water supply to irrigate their own lands at the expense of the Muslim cultivators. In the ensuing repression, Muḥammad ‘Allāl al-Fāsī, a prominent nationalist leader, was banished to Gabon in French Equatorial Africa, where he spent the following nine years.

As previously noted, parts of Morocco were under Spanish rule, while others were part of the French protectorate. It is helpful to examine the events of mid-20th century Moroccan history through these divisions.

At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the sultan issued a call for cooperation with the French, and a large Moroccan contingent (mainly Amazigh) served with distinction in France. The collapse of the French in 1940 followed by the installation of the German collaborationist Vichy regime produced an entirely new situation. The sultan signified his independence by refusing to approve anti-Jewish legislation. When Anglo-American troop landings took place in 1942, he refused to comply with the suggestion of the resident general, Auguste Noguès, that he retire to the interior. In 1943 the sultan was influenced by his meeting with U.S. Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had come to Morocco for the Casablanca Conference and was unsympathetic to continued French presence there. The majority of the people were equally affected by the arrival of U.S. and British troops, who exposed Moroccans to the outside world to an unprecedented degree. In addition, Allied and Axis radio propaganda, both of which were supportive of Moroccan independence, strongly attracted Arab listeners. Amid these circumstances, the nationalist movement took the new title of Ḥizb al-Istiqlāl (Independence Party). In January 1944 the party submitted to the sultan and the Allied (including the French) authorities a memorandum asking for independence under a constitutional regime. The nationalist leaders, including Aḥmad Balafrej, secretary general of the Istiqlāl, were unjustly accused and arrested for collaborating with the Nazis. This caused rioting in Fès and elsewhere in which some 30 or more demonstrators were killed. As a result, the sultan, who in 1947 persuaded a new and reform-minded resident general, Eirik Labonne, to ask the French government to grant him permission to make an official state visit to Tangier, passing through the Spanish Zone on the way. The journey became a triumphal procession. When the sultan made his speech in Tangier, after his stirring reception in northern Morocco, he emphasized his country’s links with the Arab world of the East, omitting the expected flattering reference to the French protectorate.

Labonne was subsequently replaced by Gen. (later Marshal) Alphonse Juin, who was of Algerian settler origin. Juin, long experienced in North African affairs, expressed sympathy for the patriotic nationalist sentiments of young Moroccans and promised to comply with their wish for the creation of elected municipalities in the large cities. At the same time, he roused opposition by proposing to introduce French citizens as members of these bodies. The sultan used his one remaining prerogative and refused to countersign the resident general’s decrees, without which they had no legal validity. A state visit to France in October 1950 and a flattering reception there did nothing to modify the sultan’s views, and on his return to Morocco he received a wildly enthusiastic welcome.

In December General Juin dismissed a nationalist member from a budget proposal meeting of the Council of Government; consequently, the 10 remaining nationalist members walked out in protest. Juin then contemplated the possibility of using the Amazigh feudal notables, such as Thami al-Glaoui, to counter the nationalists. At a palace reception later in the month al-Glaoui in fact confronted the sultan, calling him not the sultan of the Moroccans but of the Istiqlāl and blaming him for leading the country to catastrophe.

With Sīdī Muḥammad still refusing to cooperate, Juin surrounded the palace, under the guard of French troops supposedly placed there to protect the sultan from his own people, with local tribesmen. Faced with this threat, Sīdī Muḥammad was forced to disown “a certain political party,” without specifically naming it, though he still withheld his signature from many decrees, including one that admitted French citizens to become municipal councillors. Juin’s action was widely criticized in France, which led to his replacement by Gen. Augustin Guillaume in August 1951. On the anniversary of his accession (November 18), the sultan declared his hopes for an agreement “guaranteeing full sovereignty to Morocco” but (as he added in a subsequent letter addressed to the president of the French Republic) “with the continuation of Franco-Moroccan cooperation.” This troubled situation continued until December 1952, when trade unions in Casablanca organized a protest meeting in response to the alleged French terrorist assassination of the Tunisian union leader Ferhat Hached. Subsequently, a clash with the police resulted in the arrest of hundreds of nationalists, who were held for two years without trial.

In April 1953 ‘Abd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī, a noted religious scholar and the head of the Kattāniyyah religious brotherhood, together with a number of Amazigh notables led by al-Glaoui (along with the connivance of several French officials and settlers) began to work for the deposition of the sultan. The government in Paris, preoccupied with internal affairs, finally demanded that the sultan transfer his legislative powers to a council, consisting of Moroccan ministers and French directors, and append his signature to all blocked legislation. Although the sultan yielded, it was insufficient for his enemies. In August al-Glaoui delivered the equivalent of an ultimatum to the French government, who deported the sultan and his family and appointed in his place the more subservient Mawlāy Ben ‘Arafa. These actions failed to remedy the situation, as Sīdī Muḥammad immediately became a national hero. The authorities in the Spanish Zone, who had not been consulted about the measure, did nothing to conceal their disapproval. The Spanish Zone thus became a refuge for Moroccan nationalists.

In November 1954 the French position was further complicated by the outbreak of the Algerian war for independence, and the following June the Paris government decided on a complete change of policy and appointed Gilbert Grandval as resident general. His efforts at conciliation, obstructed by tacit opposition among many officials and the outspoken hostility of the majority of French settlers, failed. A conference of Moroccan representatives was then summoned to meet in France, where it was agreed that the substitute sultan be replaced with a crown council. Sīdī Muḥammad approved this proposal, but it took weeks to persuade Mawlāy Ben ‘Arafa to withdraw to Tangier. Meanwhile, a guerrilla liberation army began to operate against French posts near the Spanish Zone.

In October al-Glaoui declared publicly that only the reinstatement of Muḥammad V could restore harmony. The French government agreed to allow the sultan to form a constitutional government for Morocco, and Sīdī Muḥammad returned to Rabat in November; on March 2, 1956, independence was proclaimed. The sultan formed a government that included representation from various elements of the indigenous population, while the governmental departments formerly headed by French officials became ministries headed by Moroccans.

The Spanish protectorate over northern Morocco extended from Larache (El-Araish) on the Atlantic to 30 miles (48 km) beyond Melilla (already a Spanish possession) on the Mediterranean. The mountainous Tamazight-speaking area had often escaped the sultan’s control. Spain also received a strip of desert land in the southwest, known as Tarfaya, adjoining Spanish Sahara. In 1934, when the French occupied southern Morocco, the Spanish took Ifni.

Spain appointed a khalīfah, or viceroy, chosen from the Moroccan royal family as nominal head of state and provided him with a puppet Moroccan government. This enabled Spain to conduct affairs independently of the French Zone while nominally preserving Moroccan unity. Tangier, though it had a Spanish-speaking population of 40,000, received a special international administration under a mandūb, or a representative of the sultan. Although the mandūb was, in theory, appointed by the sultan, in reality he was chosen by the French. In 1940, after the defeat of France, Spanish troops occupied Tangier, but they withdrew in 1945 after the Allied victory.

The Spanish Zone surrounded the ports of Ceuta and Melilla, which Spain had held for centuries, and included the iron mines of the Rif Mountains. The Spanish selected Tétouan for their capital. As in the French Zone, European-staffed departments were created, while the rural districts were administered by interventores, corresponding to the French contrôleurs civils. The first area to be occupied was on the plain, facing the Atlantic, which included the towns of Larache, Ksar el-Kebir, and Asilah. That area was the stronghold of the former Moroccan governor Aḥmad al-Raisūnī (Raisūlī), who was half patriot and half brigand. The Spanish government found it difficult to tolerate his independence; in March 1913 al-Raisūnī retired into a refuge in the mountains, where he remained until his capture 12 years later by another Moroccan leader, Abd el-Krim.

Abd el-Krim was an Amazigh and a good Arabic scholar who had a knowledge of both the Arabic and Spanish languages and ways of life. Imprisoned after World War I for his subversive activities, he later went to Ajdir in the Rif Mountains to plan an uprising. In July 1921 Abd el-Krim destroyed a Spanish force sent against him and subsequently established the Republic of the Rif. It took a combined French and Spanish force numbering more than 250,000 troops before he was defeated. In May 1926 he surrendered to the French and was exiled.

The remainder of the period of the Spanish protectorate was relatively calm. Thus, in 1936, Gen. Francisco Franco was able to launch his attack on the Spanish Republic from Morocco and to enroll a large number of Moroccan volunteers, who served him loyally in the Spanish Civil War. Though the Spanish had fewer resources than the French, their subsequent regime was in some respects more liberal and less subject to ethnic discrimination. The language of instruction in the schools was Arabic rather than Spanish, and Moroccan students were encouraged to go to Egypt for a Muslim education. There was no attempt to set Amazigh against Arab as in the French Zone, but this might have been the result of the introduction of Muslim law by Abd el-Krim himself. After the Republic of the Rif was suppressed, there was little cooperation between the two protecting powers. Their disagreement reached a new intensity in 1953 when the French deposed and deported the sultan. The Spanish high commissioner, who had not been consulted, refused to recognize this action and continued to regard Muḥammad V as the sovereign in the Spanish Zone. Nationalists forced to leave the French area used the Spanish Zone as a refuge.

Abd el-Krim in Cairo 1947. AFP/Getty Images

In 1956, however, the Spanish authorities were taken by surprise when the French decided to grant independence to Morocco. A corresponding agreement with the Spanish was nevertheless reached on April 7, 1956, and was marked by a visit of the sultan to Spain. The Spanish protectorate was thus brought to an end without the troubles that marked the termination of French control. With the end of the Spanish protectorate and the withdrawal of the Spanish high commissioner, the Moroccan khalīfah, and other officials from Tétouan, the city again became a quiet, provincial capital. The introduction of the Moroccan franc to replace the peseta as currency, however, caused a great rise in the cost of living in the former Spanish area, along with difficulties brought on by the introduction of French-speaking Moroccan officials. In 1958–59 these changes generated disorders in the Rif region. Tangier, too, lost much of the superficial brilliance it had developed as a separate zone. As in the former French Zone, many European and Jewish inhabitants left. The southern protectorate area of Tarfaya was handed back to Morocco in 1958, while the Spanish unconditionally gave up Ifni in 1970, hoping to gain recognition of their rights to Melilla and Ceuta.

Ceuta, on the Strait of Gibraltar, and Melilla, farther east on the Mediterranean coast, continue to be Spanish presidios on Moroccan soil, both with overwhelmingly Spanish populations. In October 1978 the United States turned over to Morocco a military base, its last in Africa, at Kenitra.

The French protectorate had successfully developed communications, added modern quarters to the cities, and created a flourishing agriculture and a modern industry based on a colonial model. Most of these activities, however, were managed by Europeans. In the constitutional field there had been virtually no development. Though the government was in practice under French supervision, in theory the powers of the sultan were unrestrained. By French insistence, the first cabinet was composed of ministers representing the various groups of Moroccan society, including one from Morocco’s Jewish minority. Mubarak Bekkai, an army officer who was not affiliated with any party, was selected as prime minister. The sultan (who officially adopted the title of king in August 1957) selected the ministers personally and retained control of the army and the police; he did, however, nominate a Consultative Assembly of 60 members. His eldest son, Mawlāy Hassan, became chief of staff, and by degrees successfully integrated the irregular liberation forces into the military even after they had supported an uprising against the Spanish in Ifni and against the French in Mauritania.

In general, the changeover to Moroccan control, assisted by French advisers, took place smoothly. Because of the continuing war in Algeria, which Morocco tacitly supported, relations with France were strained; close ties were maintained, however, because Morocco still depended on French technology and financial aid.

A major political change occurred in 1959 when the Istiqlāl split into two sections. The main portion remained under the leadership of Muḥammad ‘Allāl al-Fāsī, while a smaller section, headed by Mehdi Ben Barka, ‘Abd Allāh Ibrāhīm, ‘Abd al-Raḥīm Bouabid, and others, formed the National Union of Popular Forces (Union Nationale des Forces Populaires, or UNFP). Of these groupings the original Istiqlāl represented the more traditional elements, while the UNFP, formed from the younger intelligentsia, favoured socialism with republican leanings. Muḥammad V made use of these dissensions to assume the position of an arbiter above party strife. He nevertheless continued preparations for the creation of a parliament until his unexpected death in 1961, when his son succeeded him as Hassan II.

In 1963, when parliamentary elections were finally held, the two halves of the former Istiqlāl formed an opposition, while a party supporting the king was created out of miscellaneous elements and came to be known as the Front for the Defense of Constitutional Institutions. This included a new, predominantly Amazigh, rural group opposed to the Istiqlāl. The ensuing near deadlock caused the king to dissolve Parliament after only one year, and, with himself or his nominee as prime minister, a form of personal government was resumed. In 1970 a new constitution was promulgated that provided for a one-house legislature; yet this document did not survive an abortive coup by army elements against the monarchy in July 1971. The following year Hassan announced another constitution, but its implementation was largely suspended following another attempted military coup in August. The second coup was apparently led by Minister of Defense Gen. Muḥammad Oufkir; he had earlier been implicated in the kidnapping (1965) and disappearance in Paris of the exiled Moroccan UNFP leader Mehdi Ben Barka, who had been regarded as a likely candidate for the presidency of a Moroccan republic. Oufkir subsequently died at the royal palace, supposedly by his own hand, while hundreds of suspects, including members of his family, were imprisoned. Elections held in 1977, which were widely regarded as fraudulent, brought a landslide victory to the king’s supporters. King Hassan’s forceful policies to absorb Spanish (Western) Sahara gave him increased popularity in the mid-1970s. This, in addition to his method of mixing efforts to co-opt the political opposition with periods of political repression, served to maintain royal control.

By the early 1980s, however, several bad harvests, a sluggish economy, and the continued financial drain of the war in Western Sahara increased domestic strains, of which violent riots in Casablanca in June 1981 were symptomatic. The need for political reform became even more pressing when international lending agencies and human rights organizations turned their attention to Morocco’s troubled internal state of affairs.

The threat of an Algerian-style insurrection fueled by a radical Islamic opposition worried the political leadership throughout the 1990s and into the early 21st century. The government has continued to closely watch the most militant groups. Along with the disaffected urban youth who occasionally took to the streets, the Islamist sympathizers have tested the limits of a new political tolerance. Thus, the 1990s were marked by greater liberalization and a sense of personal freedom, although direct criticism of the king and the royal family were still prohibited. Amnesties for political prisoners long held in remote regions of the country signaled a new attention to human rights, while much publicized curbs on the power of the police and security forces suggested closer adherence to the rule of law.

The foreign policy of independent Morocco has often differed from that of its Arab neighbours. Throughout the Cold War, Morocco generally sided with the western European powers and the United States rather than with the Eastern bloc, whereas other Arab states usually chose neutral or even pro-Soviet positions. King Hassan helped to prepare the way for the Camp David Accords (1978) between Israel and Egypt by opening up a political dialogue with Israel in the 1970s, well in advance of other Arab leaders, and by continually pressing both Palestinians and Israelis to seek a compromise solution. Morocco closely supported the United States in the Gulf War (1991) and its pursuit of peace in the Middle East. Unlike other Arab states, Morocco has maintained ties with its former Jewish citizens who now reside in Israel, Europe, and North and South America.

Morocco’s relations with neighbouring North African states have not always been smooth, especially those with Libya and its leader Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi. Shunning the Libyan leader’s volatile political style, Hassan nevertheless tried, in the 1990s, to reintegrate Libya into the Maghribī fold. Events in Western Sahara disrupted relations with Algeria beginning in the early 1970s, because Algeria generally opposed Morocco’s policies there.

From the mid-1970s King Hassan actively campaigned to assert Morocco’s claim to Spanish Sahara, initially using this nationalist issue also to rally much-needed domestic support. In November 1975, after a UN mission had reported that the majority of Saharans wanted independence and had recommended self-determination for the region, Hassan responded with the “Green March,” in which some 200,000 volunteers were sent unarmed across the border to claim Spanish Sahara. To avoid a confrontation, Spain signed an agreement relinquishing its claim to the territory. The region, renamed Western Sahara, was to be administered jointly by Morocco and Mauritania. By early 1976 the last Spanish troops had departed, leaving Morocco to struggle with a growing Saharan guerrilla group named the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Río de Oro (Polisario), actively supported by Algeria and later by Libya.

Hassan offered to hold a referendum in the area in 1981, but it was rejected by the Polisario leadership as being too much on Moroccan terms. Fighting continued, and Morocco was able to secure some two-thirds of the territory within defensive walls by 1986. In the meantime, the territory’s government-in-exile, the Saharan Arab Democratic Republic, won recognition from an increasing number of foreign governments. Improving ties between Morocco and Algeria beginning in 1987–88, along with a UN-sponsored peace proposal accepted by Morocco in 1988, augured a solution to the problem, but military action by the Polisario the following year prompted King Hassan to cancel further talks.

In 1991 a UN Security Council resolution promised the most definitive solution to Morocco’s claim to Western Sahara in 15 years. The resolution called for a referendum on the future of the territory to decide whether it should be annexed to Morocco or become an independent state. However, both Morocco and the Polisario front were unable to agree on the makeup of the voter lists for the referendum, fearful of entering into an electoral process they might lose. Although agreement on other issues such as political detainees and prisoners of war was reached through UN mediation, stalemate over the code of conduct of the referendum has continued, leaving the issue unresolved.

By the end of the 1990s, King Hassan II had the distinction of being the Arab world’s longest-surviving monarch. Actively promoting a program of liberalization in Morocco, he managed to recast an image of an old-style autocrat, reshaping himself and his country to reflect more progressive values. New political freedoms and constitutional reforms enacted in the 1990s culminated in the election of the first opposition government in Morocco in more than 30 years. In 1997 opposition parties won the largest bloc of seats in the lower house, and in March 1998 Abderrahmane Youssoufi (‘Abd al-Raḥmān Yūsufī), a leader of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces, was appointed as prime minister. Under pressure from human rights organizations, Hassan also directed a vigorous cleanup campaign that led to the ousting and even execution of corrupt officials as well as the release of more than a thousand political detainees, some of whom had been held for nearly 25 years. Despite these major political reforms, the king retained ultimate political authority, including the right to dismiss the government, veto laws, and rule by emergency decree.

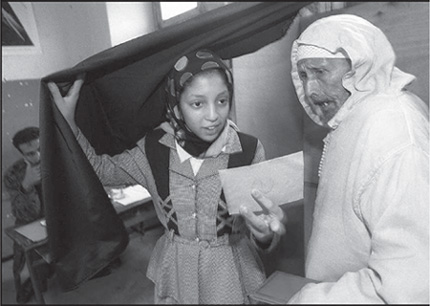

A Moroccan girl helps her illiterate father cast his vote outside Rabat, Nov. 14,1997. The parliamentary elections marked the first time since independence that voters elected all the country’s deputies by universal suffrage. Abdelhak Senna/AFP/Getty Images

Hassan also guarded his status as religious head of state and carefully nurtured those aspects of his public image that garnered widespread support in the countryside and among the urban poor. Using public donations, he oversaw the completion in August 1993 of a huge $600 million mosque built on the shoreline at Casablanca, which features a retractable roof and a powerful green laser beam aimed at Mecca from atop its towering minaret. Paradoxically, his main political foes were also found in the religious arena, among the Islamic militants, whom he tried to hold within strict limits. But even at this point of contention, he showed some flexibility: In 1994 a number of political prisoners with ties to religious groups critical of the monarchy were pardoned by Hassan, and in December 1995 Abdessalam Yassine (‘Abd al-Salām Yāsīn), the leader of the outlawed Islamic organization The Justice and Charity Group (Jamā‘at al-‘Adl wa al-Iḥsān), was released after spending six years under house arrest.

When Hassan died in July 1999, his son, Muḥammad VI, took up the reins of government and immediately faced a political maelstrom. Controversy raged in Morocco over government proposals to afford women broader access to public life—including greater access to education and more thorough representation within the government and civil service—and to provide them with more equity within society, such as greater rights in marriage, inheritance, and divorce. A liberal program of this type, in Morocco’s conservative and religious society, fueled dissent among Islamic groups, and a number of organizations—ranging from Muslim fundamentalist groups to members of international human rights organizations—gathered in large demonstrations in Casablanca and Rabat to support or oppose the government’s program. The country saw an increase in violence, including suicide bombings in 2003 and 2007, which led the government to impose more stringent security measures.