DAVID GORDON

Forthright in movement, quick-witted in words, David Gordon is the smart, funny boy next door. Though he moves with fluency and efficiency, he doesn’t look like a highly trained dancer. With thick black hair, a strong body, and a readiness to address the audience, he can seem more like an actor than a dancer. He easily takes up the mic, often controlling the stage action with his ad hoc, absurdist situation comedies. He is quick to catch us off guard, spin an outlandish yarn, or change the way we see a mundane object. He’s sly, sassy, sardonic, with a comedian’s sense of timing and a playwright’s verbal command. And when a boyish excitement comes over him, he can whip up a whirlwind of rollicking energy.

David Gordon (born 1936) grew up on the Lower East Side, in the bosom of what he calls a “loving battling—claustrophobic—Jewish family.”1 He listened to Bob and Ray and Let’s Pretend on the radio and went to the weekly double feature at the local movie house. When television came in, he watched comedy shows like Milton Berle and Sid Caesar & Imogene Coca: Your Show of Shows. He also borrowed about eight books a week from the local library, which surely contributed to his outsized verbal ability. As a teenager he wrote stories and illustrated them for the school magazine, winning the school art medal at graduation. At Brooklyn College, he studied with some of the major artists of the day2 and developed an interest in photography. His New York/Yiddish accent was so strong that he was sent to a speech clinic. He followed one girl to the modern dance club and another to the theater department, where he was instantly cast as the lead in a play he did not audition for. The director must have thought he was perfect for the soulful witch boy in Dark of the Moon.

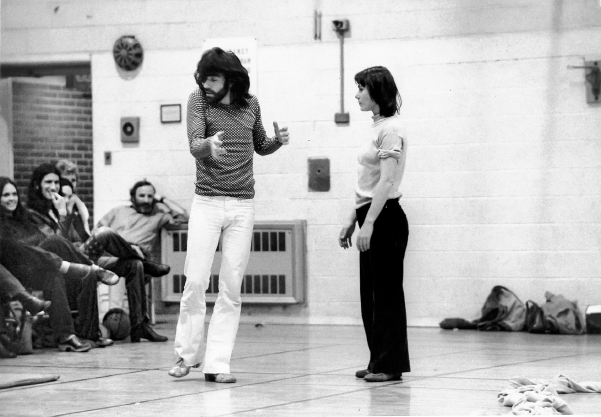

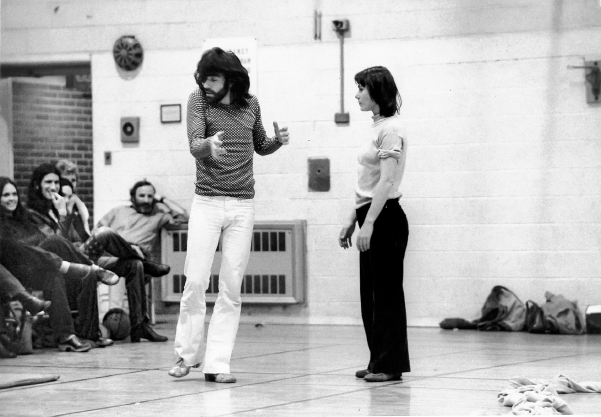

GU in NYC Dance Marathon, 14th Street Y, 1971. From left: Gordon, Rainer. Visible in the audience are Chilean pianist and artist Fernando Torm, wearing boots, and Richard Nonas, leaning on radiator. Photo: Susan Horwitz, courtesy Douglas Dunn.

While hanging out in Washington Square Park in 1957, he happened to meet the choreographer James Waring. Assuming Gordon was—or should be—a dancer, Waring invited him to a rehearsal. There Gordon met the newly arrived British dancer Valda Setterfield, and the rest is history: the two married the following year and have been working together ever since. Gordon created his first duet with Setterfield, Mama Goes Where Papa Goes (1960), and performed it on a program of Waring’s students at the Living Theatre. He used a chance method in the process: “[t]earing up pieces of paper and tossing them into a hat.”3

Through Waring, Gordon gained exposure to a motley assortment of artists: Cocteau, Buñuel, Laurel and Hardy, Fanny Brice, Balanchine, Kurt Schwitters, Morton Feldman, Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Maria Tallchief, Groucho Marx. And, Waring advised, “You must see Yvonne Rainer’s Ordinary Dance; it is extraordinary.”4

Also eclectic were Waring’s costumes. Gordon described getting outfitted for the first piece of Waring’s he was in: “All the dancers wore costumes designed by separate artists. Nobody knew what anybody else was wearing and I didn’t know what I was wearing at all until the day of performance when Paul Taylor (who Jimmy called Pete) placed half spheres on my shoulders and back and chest and on my head and painted my crotch green through my tights.”5

But there was another strong influence when it came to costumes. Gordon’s day job was dressing windows for Azuma stores, which sold Japanese lanterns and other furnishings. “I began to travel regularly to Japan w/Sato brother—of Azuma stores—stayed in hotels—‘yukatas’—cotton sleeping kimonos provided—took ’em home. Also—looked for Japanese paraphernalia—to sell in Azuma stores as exotica—visited street mkts—found piles—small mtns—of secondhand kimonos—including yukatas—persuaded Azuma to buy n’ sell ’em—also bought ’em as gifts for family & friends.”6

His access to what was considered exotic costumes and the way he moved in them—often slowing down—changed not only his own performance but also sometimes the whole feeling in the room. In one of the 1975 La MaMa performances, while Gordon wore a dark robe that made him appear like a “mournful Bedouin,”7 at one moment all six dancers formed a linear tableau that transported us to some ancient world. Paxton asked for “my song,” which turned out to be a soupy instrumental version of “Go Down Moses.” The dancers stood in a row, holding hands, looking like six sorrowful nomads about to traverse the desert. They seemed to take on the weight of history and the mysteriousness of a faraway culture. Then, when the song changed to a sped-up version of “Look Away, Dixie Land,” the tableau erupted into crazy energy, with everyone dashing around in circles.

Although Gordon’s fantasies had the power to gather others into his world, you always knew that the person inside the getup was David Gordon. He was always himself no matter how outlandish the outfit. He could pretend without pretentiousness. As a young man, “I chewed on theater and television and film and literature and the things that interested me personally, none of which I thought about in relation to anything called ‘art.’”8

When Waring, then Rainer, then Brown, came into his life, he began to recognize that he was participating in making art. “Jimmy taught me about art and developed my taste, but I didn’t begin to understand about making work until later, when I performed with Yvonne Rainer. From her I found out what it is to be an artist—a person who makes choices and stands behind them. Then, from working with Trisha Brown in the Grand Union, I learned how to edit, how to boil a thing down to its essence.”9

He had already encountered movies by W. C. Fields and the Bob Hope/Bing Crosby team in which they make side comments directly toward the camera. He later saw Mike Nichols and Elaine May, who staged an argument so realistically—including his hitting her—that David gasped to see them smile and bow afterward. He learned that “somehow a performance could be disrupted in a way which allows you to … have what seems like a drama and then you can undercut the entire drama which turns it into a surreal drama or a comedy.”10 (This kind of deceiving the audience also tied in with David’s fondness for trompe l’oeil, which he learned about in a commercial art course in Brooklyn College taught by Ivan Chermayeff.)11

His ability to take a nearby object and transform it into something else he attributes to studying art at Brooklyn College: “My training had very little to do with drawing a line from here to there…. and the courses were much more concerned with looking around you. Instead of seeing material as something used only for self-expression, I become aware of material itself and of how I could manipulate it and change its reality.”12

Looking around in one’s environment led to the use of found objects. The bloody lab coat Gordon wore for Mannequin Dance (1962) was given him by an artist friend who taught biology.13 Another kind of found object served as a source for Sleep Walking (1971), which he made when Rainer, on her way to India, asked him to keep a group of her students occupied. He brought to these students what he had been watching: “[I]n the streets of New York at that time are a lot of addicts, and they are nodding out in the street…. In the night because I’m not sleeping very well, I take a walk and there are these junkies nodding out … and they are so far off balance and they don’t fall. So I start practicing to see if I can do what they do. How far off balance can I be with my eyes closed without falling over? And reaching for something that’s down there, inevitably some piece of dope that they were after, which they never get.”14

David’s antennae were up when he visited St. Vincent’s Hospital, where Steve was recovering from an operation. The frail old man who shared the room with Steve would periodically slip downward. He would moan, “Oh god, I’m slipping” until a nurse came to prop him up in his chair. He would slip, moan, and be rescued again. That memory lingered with David, not only for its human vulnerability but also for its repetition. It found its way into Grand Union performances, providing a breakthrough for David, who up until then was just repeating variations of Rainer’s Trio A in GU performances.

The most obvious and constant gift he brought to Grand Union was his quick-witted, off-the-cuff narrative making. The litany of questions he posed to Barbara in the beginning of the 1974 Iowa performance was a literary accomplishment in its quick associations, fantasies, and word play. (I provide snippets of this passage in chapter 19.) Another example is the changing fortunes of the bed-wetting orphan, which I refer to in the next interlude.

He also had a gift for physical comedy. In the La MaMa performance in 1976, he had gotten caught between two very agile “leaders,” Barbara and Douglas. He lurched and flipped and toppled while trying to imitate Barbara’s smooth movements and Douglas’s sturdy positions. If you didn’t already know that Laurel and Hardy were two of David’s heroes, you could guess it by watching this episode. At times like these, the audience couldn’t get enough of him.

But it wasn’t always smooth sailing for David. Even though he had improvised in his sixties works like Random Breakfast, he balked when others in the early, waffling period of Grand Union suggested they all improvise together. He was still feeling the whammo of a negative response to his piece Walks and Digressions in 1966. The audience had actually booed, and the Village Voice came out with a scathing review. (One choice put-down: “[T]he performer is stranded in his own vacuum of self-indulgence.”)15 After that damning review—from Yvonne’s boyfriend, Robert Morris, no less—David decided “not to risk that anymore.”16 He gave up choreography for six years. It wasn’t until he came up with the “Oh god, I’m slipping” bit that he summoned the confidence to initiate an action. He soon developed a repertoire of ways to channel his quick imagination into action. The David Gordon we were getting in Grand Union was a man embarking on a fresh start. He was rediscovering his abilities as a mover, improviser, storyteller, framer, and entertainer.

Although David loved the spotlight, he also honored the group as a whole. In 1973, while telling Robb Baker about the recurring motifs, which he called “collective unconscious references,” he said, “Grand Union performances are full of them. It’s like everyone adding his breath to one big balloon.”17 And although he often dominated scenes with his easily spun narratives, he was very aware of what the others contributed. “I always hope that my excess is balanced by Steve’s sincerity,” he told Banes.18

There were times when he instinctively knew to give over the spotlight. One of those times was during an informal performance at Oberlin, when it was suggested that Nancy dance the whole of Ravel’s Bolero by herself. He recalled, “I sat down and I remember thinking, I cannot turn my head away from watching Nancy. I cannot appear to have any opinion about what it is I am doing because the audience will see me see her so I have to just sit still and concentrate on [it.]”19

Another gift of David’s was the unexpectedly tender quality of his touch. (I say unexpectedly because his usual irreverence does not prepare you for it.) In scenes where he was slowly touching—almost caressing—Paxton, Lewis, Brown, or Dilley, his focus was loving, sensual, and absorbed. He was also completely reliable when a falling person needed to be caught. This kind of dependability, which had been developed during CP-AD, fostered an environment in which people knew they could take risks.

And another gift was sheer spontaneity. Gordon could come up with instant variations in a sparring match; he could burst into song (he has a deep, pleasing singing voice). Spontaneity meant being “in the moment,” which was a catchphrase of the time, related to Baba Ram Dass’s popular book Be Here Now.

Being in the moment means not only following through with one’s impulses but also yielding to the wishes of someone else. As David has said,

“In the moment.” I never heard the phrase until I got to the Actors’ Studio, and actors talk all the time about being “in the moment.” I realized that is what I learned in the Grand Union—to be in the moment. Not only thinking I wanted to do the thing I wanted to do next, but to watch the thing I wanted to do next get subverted by somebody else’s thinking what they wanted to do next, and determine what was the next in-the-moment thing that needed to happen between those things, to make them both coexist, to make one of them go away, or to make one of them become the major piece of material that was happening.20

Lastly, David’s keen sense of framing has been consistent from college days onward. At Brooklyn College, “[w]orking on photos in the darkroom made a big difference as I learned to edit and refocus the photo I originally took.”21 His understanding of the rectangle served him well later as a window designer, and still later as a collaborator in a performance space. In Grand Union he always had a feel for the larger picture, for the multiplicity of things that could be going on in a single, framed space.