STEVE PAXTON

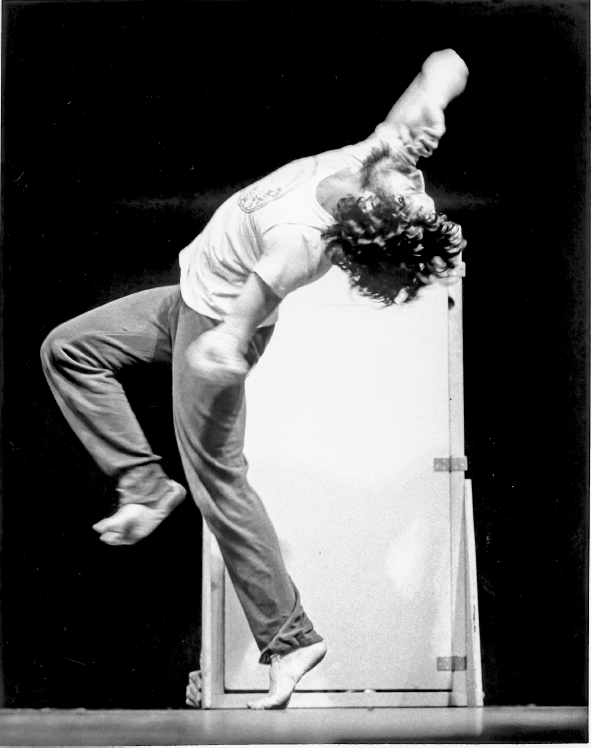

With a long neck, sloping shoulders, and a Greek-god-like face, Steve often initiates movement from the head, with the spine following in snaky succession. His sculpted shapes could suddenly go soft, a solid transforming into a liquid before our eyes. When he’s got momentum, he can drop into a crouch and spring back up in the blink of an eye. But when he decides to go slow, nothing can rush him. He stays rooted, feet planted on the floor, playing with weight shifts in different parts of the body. That kind of play easily extends to other bodies: his readiness to touch or be touched, lean or be leaned on, is a staple of Grand Union’s physical explorations. He is divinely comfortable in actions that would be disorienting or awkward for other dancers: tilting way off balance, hanging upside down, or balancing on his elbows. His solemn demeanor lends a sense of gravitas, making his occasional sly quips all the more surprising.

Steve Paxton (born 1939) grew up in Tucson, Arizona, where he excelled in gymnastics. At about the age of six, he was doing cartwheels.1 He toured with a school group, then went off to the University of Arizona, down the street from his house. He found the teachers decidedly unstimulating, especially for his favorite subjects, English and microbiology. About his English teacher, he said, “I felt like he was teaching Snobbism 101.”2 But he had enjoyed the classes in Martha Graham technique he had taken in Tucson, so he accepted a scholarship to the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College the summer of 1958. Although José Limón had provided the financial aid, it was his encounter with Merce Cunningham’s work that intrigued him. That fall, Paxton came to New York, where he continued studying with both Limón and Cunningham.

When Paxton enrolled in Robert Dunn’s composition course at the Cunningham studio in 1960, he met Forti and Rainer. Eventually Trisha Brown and David Gordon joined the class too. Gordon has a clear memory of Paxton in those classes: “Steve Paxton, as he has done most of my ever knowing him, would ask the damnedest questions which turned the world upside down and put everybody on the spot.”3

In 1961 he took part in Forti’s “dance constructions” at Yoko Ono’s loft on Chambers Street. These works (Huddle, Slant Board, and Herding) jolted him into a state of mind he characterized as “the primal naked mind.” They made him question all his dance training. Forti was not going for a dancerly look but for functional movement that engaged with certain objects. For Paxton, the effort to shed his training “was self-shaking, paradoxical, and enlarging”4—a good preparation for improvisation.

Forti’s earthiness balanced out Cunningham’s highly technical choreography for him. Seeing her crawl on all fours after a Cunningham class (probably around 1960), he felt she was trying out “evolutionary pathways” that led to “a whole way of looking at the person not as a tool, an aesthetic tool, but rather an organic part of the earth.”5

Paxton performed in works by Rainer and Brown as well as his own, in and around Judson Dance Theater. He was also in performance pieces by Robert Rauschenberg, who was his life partner during those years, including Spring Training (1965), Map Room II (1965), and Linoleum (1966). In Map Room, he walked with his feet inside the rims of car tires. In Linoleum, he lay, belly down, encased by a narrow tube of chicken coop wire, as he ate fried chicken and looked around at the live chicks behind him.6 Paxton was affected by Rauschenberg’s performances as well as his sense of community. “Rauschenberg proposes a community of artists who, by seeing one another’s work, weave a complex web of transmissions and permissions.”7

But he also experienced Rauschenberg’s work—and that of others at Judson—as a challenge: “Rauschenberg’s whole raison was to expand possibilities. He was fearlessly and endlessly inventive, and a masterful theater-mind. So between him and Cunningham, I had a lot to avoid copying. Plus avoiding the work of my Judson colleagues.”8

Steve Paxton in GU performance, Guthrie Theater, Walker Art Center, 1975. Photo: Boyd Hagen, courtesy Walker Art Center.

His early performances at Judson progressed at such an unhurried pace that viewers were either annoyed, bored, or amazed. His choreographic decisions in some ways reacted to the aesthetic environment of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, where he danced from 1961 to 1964. He wrote that he was consciously countering the “glamour of Cunningham and the speed and the pacing and the Rauschenberg costumes … all the sparkle that could be generated.” Looking back, he called his early work at Judson “tedious.”9 Rainer, impressed with his spirit of resistance, wrote that Paxton maintained “a seemingly obdurate disregard for audience expectations.”10

Disregard for the audience might not seem like an ideal attribute for a performer. But that kind of obduracy almost guaranteed that Grand Union would not easily cave to audience expectations. Paxton’s stubbornness, his insistence on exploration over entertainment, was grounding for the rest of the group.

He had an insight into the transformative nature of objects, possibly influenced by Forti and Rauschenberg. One example during the Judson days was Music for Word Words (1963). What started as an attempt to create sound for his duet with Rainer, Word Words, using an industrial vacuum cleaner, ended as an indelible image of a man lost in a room-sized bubble of his own creation. Examples during Grand Union are the gym mat that he used to stir up the crowd, as we will see in chapter 14 on the Oberlin residency, and the cloth tubing in a performance at NYU. On this last occasion, he wriggled into this pink cloth and seemed to get stuck inside it. Douglas and Nancy were showing concern for him, hidden as he was. Eventually he emerged from the tubing, totally fine and totally nude.11

The deadpan that came naturally to all the Grand Union performers was an area that Paxton had already investigated in concrete, and at times bizarre, ways. Rainer reports that in English (1963), he asked the twelve dancers to “erase” their features using a bar of soap.12 Another strategy was to displace the dancer to a different environment, thereby putting the facial expression in a different context. In Afternoon (A Forest Concert), also in 1963, he brought dancers to perform in a forest near Murray Hill, New Jersey. “I wanted to see the abstracted face of technical dance in a forest.”13

The agility Paxton gained from gymnastics and modern dance training, combined with Forti’s “evolutionary” influence, created a highly kinetic movement language. For example, in the video of Continuous Project—Altered Daily at the Whitney Museum, he is seen swooping one leg up and over, causing him to dip, holding his body low, and then whipping himself into a high arch. He was working on a specific sensation, probably having to do with his core as the fulcrum while his limbs swerved off balance. He was not thinking of how to make it “interesting.” If anything, he wanted it to be ordinary—per Robert Dunn’s class. But in the search for the ordinary, he would take extraordinary risks. When his proposal to have forty-two red-headed nude people perform at NYU was deemed “obscene” by the powers that be, he replaced it with Intravenous Lecture (1970), in which a medical assistant injects him with a needle while he talks about censorship. In his irreverent way, he was asking: What, really, is obscene?

GU at Eisner Lubin Auditorium, NYU Loeb Student Center. Performance to benefit the Black Panther Defense Committee, 1971. From left: Paxton, Dilley, Rainer. Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Premium Collection/Getty Images.

Stillness was a ploy that came in handy in Grand Union, and Paxton could be still for a very long time. In the last LoGiudice performance, he stretched out on the floor, opposite Trisha, both of them belly down. Although she got up and left, he held this position for six minutes no matter what or who was swirling around him. He could have been a bear rug, or some low-lying sculpture that had to be circumvented.

Paxton’s preoccupation with walking lent a pedestrian pacing that anchored Grand Union in the everyday. He walked while telling stories; he walked when he was checking out the lighting instruments or looking for a prop; he walked to offset more theatrical scenes. In a statement that sounds like a Zen koan, he said of his sixties investigations, “My question was walking, and my answer is … walking.14

Paxton was wary of hierarchies of all types. His ideal in Grand Union was for everyone to “participate equally, without employing arbitrary social hierarchies in the group.”15 He felt that a leaderless group helped defray the effects of what he called “volunteer slavery.” That was his term for the unexamined life of following the leaders in our society (or, in the dance world, following a choreographer). Needless to say, his work in Contact Improvisation aimed to replace this kind of hierarchy with a physical form of equality.

Steve had a wry, at times fanciful, sense of humor. He once took up the mic and wove a fictitious tale of “Trisha the wild child.”16 In the Tokyo performance, he sat close to Barbara and Trisha during their kooky gymnastics and narrated how it looked to him: “The camel sees its reflection,” or, “The mother kangaroo and her teenage son.” Watching Douglas hanging over a pole, he announced, “The bird falls asleep on a branch.” Or he would bring the mic to his own lips but not speak. He rode many avenues toward subterfuge.

His juxtapositions of the ordinary and the absurdist were very Cagean, very Dada Zen.17 He could take ordinary objects and give them a new context. In Proxy (1962) at Judson, he included “an aluminum pan, a bucket, or a dishpan.” In that piece he had Yvonne stand in a taped off square and eat a pear. “I ate it as you would eat it at home.”18 The aim, for both Steve and Yvonne, was to do things the way you would if the audience weren’t there. That anti-showy functionality came into play during the many times he moved furniture around in Grand Union—chairs, sofas, lamps, electric fans—with a workmanlike demeanor. And yet there was also a drama within that functionality.

Steve’s commanding presence was softened by an openness to touch and release. While engaged in shaking a carpet out in the Walker Lobby performance, he softened immediately as Douglas took hold of his waist and spun him around—and then, just as readily, resumed his task with the carpet.

Steve was a quiet renegade, so consistently subversive that Rainer called him “the fly in the ointment.”19 About the sixties at Judson, she told Artforum, “I think Steve’s work was the most far-out—and kind of arcane—of everything that went on there. His stuff was the most resistant to pleasureful expectations. He was physically so gifted but absolutely refused to exploit these gifts.”20

By the time of Grand Union, he was willing to deploy those gifts—at just the right moments.